CHAPTER 8

PRODUCER

As opposed to the smell or taste of the group, some of the ineffable quality of “feeling” can actually make it onto the record. The group that lacks great sonic ability but is endowed with a “good feeling” must attempt to translate it to tape as best they can. One can also balance one’s “bad feeling”—if one is thus burdened—with the good vibes of a particular record producer.

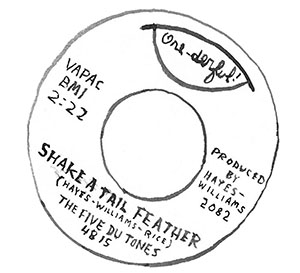

A producer is different than someone who engineers a recording. While the engineer is a technical troubleshooter—plugging in microphones, pressing buttons, and “running” the recording studio—the producer is a kind of juju man (or woman) who is hired to create the desired “vibe” for the record. “Producer” is a freewheeling title which applies to a number of roles. Some producers match songs to particular singers, some are aural theorists, others are conceptualists, and many are akin to medicine men or shamans. All are hired to give the record a personality, sensibility, or “feeling” which the group thinks will balance or augment their own.

The most successful producers have labored to create a distinctive brand name for themselves. Personal eccentricities are invented, amplified, and nurtured so as to spread the producer’s legend. A mythic history of erratic behavior by the producer will give a boring or ho-hum group’s record an easily digested narrative, so unbalanced producers are sought out and paid extra to hold a gun on the musicians, take eighteen months to mix a single song, defecate on the mixing board, and so on. The really famous producers are synonymous with such anti-social “rebellious” antics and the mere invocation of their name raises eyebrows and can help move an associated group’s record “units.”

When one is recording a song, one will typically record onto several “tracks.” Once, groups recorded all together at the same time onto a single track of tape. Eventually a single thread of tape with distinct parallel tracks was developed, and multitracking became possible. Typically these different tracks will be used for individual instruments, sound effects, or voices—whatever the group deems necessary for the tune. Depending on the technology, there could be anywhere from one to an infinite number of these audio tracks available. Tracks that are leftover after the completion of the basic instrumentation can be used for “overdubs,” double-tracking (a voice or instrument repeating or “doubling” their part), or secret backward messages about drugs and satanism. The process of recording onto tracks might require that individual instrumentalists are separately taped, sometimes at different times.

Such isolation will reveal the musician’s foibles and mistakes, which can undermine confidence and endanger the gestalt the group relies on when it plays as a cadre. This sort of exposure will create insecurity and will result in tears, lashing out, drama, and general unpleasantness. When the group is in this state of self-examination, it is at its most vulnerable. This is a reason the producer is employed—to provide an outside voice that will encourage the group to maintain civility toward one another, to rally their esprit de corps, and to act as a messiah, sin-eater, philosopher, therapist, and fall guy.

After the basic tracking is done (backing instrumentation, e.g., drums, bass, rhythm guitar), the singer or singers (if there are any) “lay down” their contribution. Singing alone in a vocal booth will exacerbate both the singer’s sense of self-importance and also group resentment toward her or him. This is an inevitable dynamic of groupism. The record producer is vital for extinguishing interpersonal animosities amongst group members in the studio. As the disposable “outsider” in the recording scenario, the producer may be utilized by the singer as a scapegoat or foil to deflect the group’s hatred toward him or herself. Or the producer can be enlisted as an ally and confidante—the singer’s true artistic collaborator and equal.

After the recording is made, the mixing will commence. This is treated as a magical ceremony of technical midwifery that takes days or weeks, and sometimes months. It was once called “balancing,” as it involves determining the relative levels of the various instruments and voices as they are mixed to a “master” or final version. The different instruments can be treated with sound effects such as reverb and delay in mixing as well, and the various tracks can be “panned” left and right to various degrees if one is mixing into stereo (which is an attempt to create a visual picture of a group, with the picture field being a spectrum of sound). Indeed, the mixing process in rock ’n’ roll is much like oil painting during the period of fine art. Monomixing, generally abandoned in the mid-’60s, was more akin to making monotypes or silk screens.

There are many songs, particularly in the early hip-hop and dance genres, which mythologize the mixing of records (Zapp & Roger’s “In the Mix,” Pretty Tony’s “Fix It in the Mix”). The idea was that if one gets the mix right, it will be the deciding factor, the special something which launches a hit record. But this is actually a producer’s egotism, as the mix can’t introduce humor, pathos, or a bewitching melody to a song that doesn’t have it. The mix will give the record a particular sensibility, though, and alert the listener to a group’s value system and intentions (i.e., the relative loudness of drums with regard to usefulness for dancing; or the deployment of reverb, which is often meant to imply “dreaminess” or “surreality,” which could intimate an escapist or occult ideology).

Once the record is mixed, it is sent to a mastering engineer. “Mastering” is a process of crushing the high and low frequencies to a tolerable medium that can be enjoyed by some imaginary general populace. After the record is mastered, a test pressing will be sent to the group for approval. You need not listen to it. It will sound different to you than it does to the other people who hear it anyway, just as you appear differently to others than you do to yourself. Why stare into the mirror endlessly, when one can never truly see oneself? Simply make sure you don’t have food on your face and then move on.

Just as you can’t truly see or hear what you do, groups you know personally will sound differently to you than groups you don’t know. Therefore, in the beginning of one’s career, ingratiating oneself to the audience is of great importance. Like a politician stumping, you will need to kiss babies, rub elbows, and press flesh. But later, when notoriety is attained, you must volte-face and shun the crowds.