CHAPTER 17

DISCIPLINE

Every group must have its own code of discipline. Rock ’n’ roll claims that it wants to spread chaos and “destroy passersby,” but one must remember: there are two types of chaos. There is, on the one hand, the chaos embodied by the stray dog, which runs furiously in whatever direction until it is overcome by fatigue. On the other hand there is the chaos created by an earthquake, avalanche, or improvised explosive device.

The latter type of chaos is the desirable sort. But for lava to surge forth in a fiery plume from the bowels of the Earth takes considerable effort on the part of the volcano. It doesn’t issue forth after a day spent at the beach or from a midafternoon hangover. No! It boils forth in such a way because of tension and torsion built up after an extraordinary amount of time. Similarly, for the group to reach such a state of abandon, one must first subject it to an iron regimen of unrelenting severity.

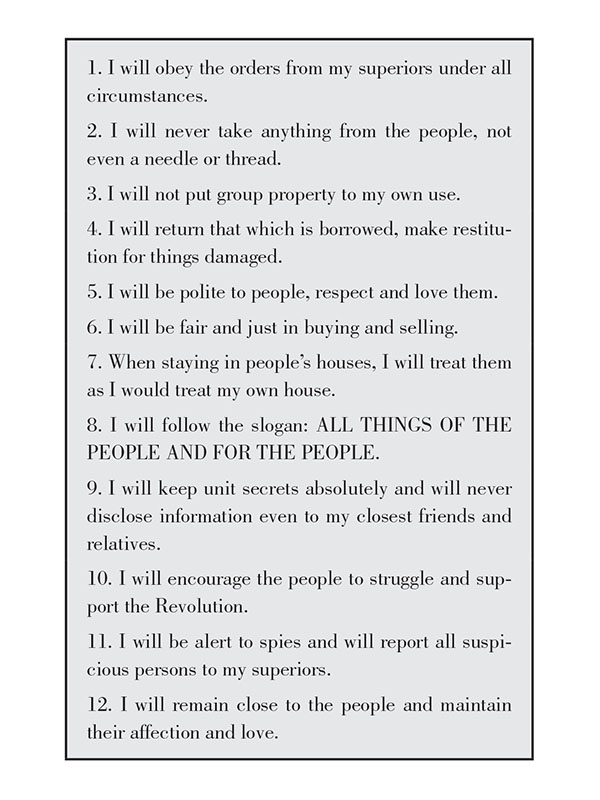

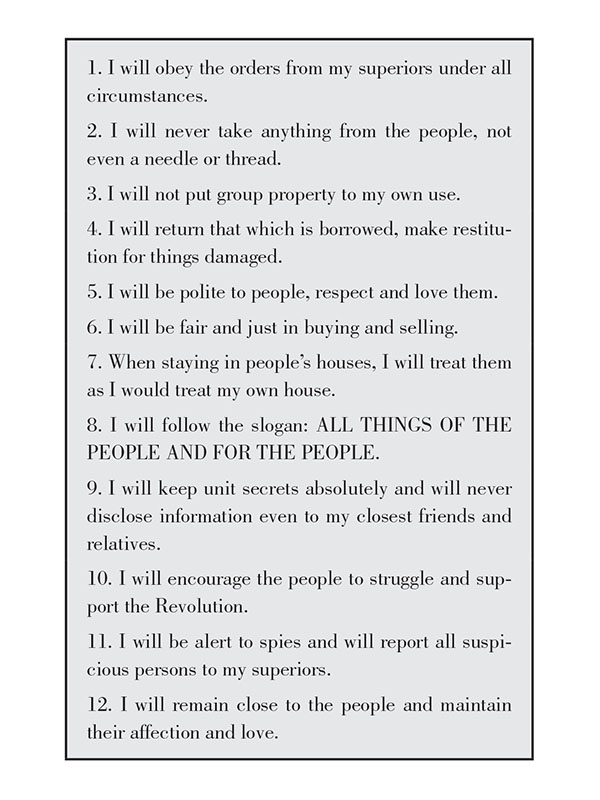

A good example of an effective guideline for such a regimen is the Vietcong Code of Discipline, which was designed for people whose lives depended on the goodwill of an underground network of supporters, just as yours shall.

Since we will be using the VC Code as a model, let’s examine its dictums a little bit closer.

1. I will obey the orders from my superiors under all circumstances.

This might be difficult for the rock ’n’ roller, sworn as he or she is to have disdain for all authority. But this maxim could be read as “obeying the order from the group,” since the group’s mission is, at least in the beginning, an acceptable authority for the group member. This is a poignant dictum, as rebellion might foment even within the group, as it did with James Brown’s Famous Flames or when Paul McCartney took the reins of the Beatles after the death of Brian Epstein. The others grew to resent him and eventually cast him from their clique. During the solo period of the ex-Beatles, Paul—like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer—was never permitted to play on the others’ records, though the rest of them frequently “guested” on each other’s.

2. I will never take anything from the people, not even a needle or thread.

This seems like an odd rule since stealing is what rock ’n’ roll is based on. The groups one plays with will steal your song ideas, your lyrics, your stage presentation, and even your style and demeanor. You will have stolen these things from records you have heard, books you have read, and films you have watched. The sound engineers will steal your microphones and your guitar cords (or vice versa), while people “hanging out” backstage will steal your beer, your computer, your money, and your address book. Meanwhile, junkies outside the club will steal your luggage, your gear, and your van. People at the show will steal your records and T-shirts from your souvenir stand.

But for the group, the “people” of #2 means the audience. As a group member, you must not steal from the audience. Not because you exist on a high moral plateau, but because it wouldn’t look good to be stealing their look, their behavior, or their boyfriend/girlfriend. You must lead with your style, your presentation, and your poise. “Imitation is the greatest form of flattery,” it’s said, and one should never flatter one’s audience. They won’t respect it. Likewise, when the audience or the other groups steal from you, it accentuates your position of primacy.

3. I will not put group property to my own use.

This seems simple. There are things that might be owned in common by a group, which should not be exploited by the individual group members for their own ends.

The van is a typical example. Based on such an order, one must dissuade a group member from using the band van to go on a date or buy groceries or attend yoga class or crochet club. Such usage might jeopardize the van by risking a wreck, or putting unnecessary wear on the engine. It could likewise breed resentment in the other members, who would like to use it for their own chores. However, this simplistic reading of the rule might ignore more important aspects of the true nature of the group.

It should be determined, for example: who exactly is the “I” and who is the “group”?

The group is obviously the sum of the organization, the sublimation of the individual concerns for the good of the whole. So the group is the total sum of personnel in the aggregate acting in tandem with one another, such as when they are onstage. But upon inspection we see that many “group tasks” are endeavored alone either by necessity or out of convenience. And when one acts for the group, one can be seen to be the group. The reason “supergroups” always fail (Velvet Revolver, CSNY) is because the bloated identities of the individuals are impediments to group cohesion.

Therefore, one must remember that the group is the one, and the one is the group. In the aforementioned scenario, then, everyone gets to use the van for whatever they want, as long as they pass a rigorous loyalty test.

4. I will return that which is borrowed, and make restitution for things damaged.

This is self-explanatory, and includes gaffer tape, morale, idealism, et al.

5. I will be polite to the people, respect and love them.

Etiquette is a very powerful tool for subjugating the masses, as has been evidenced by the British Empire, which implemented a code of politeness on their colonial subjects that kept them under the royal yoke for centuries. Politeness is an aggressive gesture, for it challenges the recipient of said manners to respond likewise. “Thank you for coming/watching us,” etc., are typical bullying tactics from stage.

And so on. The group’s code of discipline can be its own, obviously, but it must be agreed upon and understood by the entire cadre.