9.

One night, when the wind falls asleep and the moon burns a white-hot hole in the sky, I say, ‘Let’s go outside.’

Stella stops writing in her journal and looks up. ‘Why?’

‘You’re always asking questions about me, right?’ She pauses, then nods. ‘So come outside. See where I live.’

‘I dunno, maybe.’ She folds her lips tight, then says, ‘You look pale. Are you getting sick or something?’

‘It’s probably all your stupid memories. I get these pains in my chest all the time, like I’m aching.’ I don’t know why, but even my voice feels heavy.

She presses her head back against the bedroom wall, chucks her pen onto the duvet cover and keeps her eyes on me. Watching, she plucks on the end of her blue dressing gown and then laughs. Weird, but the sound has a faint echo, like it reminds me of someone I know.

‘Look, it’s not really hurting you, is it?’ She smiles, lopsided with one end twisting like a cat’s tail. ‘You’re not getting sick and you won’t die. You’re just making a fuss — the pain will go away.’

‘Are you sure about that?’

Stella turns her head sideways. I get the impression she’s pouring all her thoughts into one corner, trying to focus. She stares without moving and there’s something different about her. But it’s not her hair or clothes. At least, I don’t think so. Instead I get the feeling she’s inside herself, looking out at me.

‘Stella … ?’

‘Yeah?’

‘Lately, you don’t move as much, not like you used to.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘You couldn’t sit still. You used to drum your fingers and hands, always snapping your hair clips. You seem calmer.’

Really? She glances at her feet. ‘Well I guess that’s good. Everyone’s always telling me to stop fidgeting. When I was little …’ She stops just in time, closing her mouth over the memory. Stella looks at me and shrugs. ‘Let’s just say I wasn’t good at sitting still.’

‘Why would that annoy people?’

‘I dunno, but it did.’

Something twists inside me — someone else’s memory, I think. I’m watching knotted fingers wringing a white facecloth with blue edges over a metal bowl, until the fabric feels rough and dry. It doesn’t make any sense. I pull myself back into the room, but somehow the idea of people annoyed with Stella makes my insides feel like that cloth. So I say, ‘People are idiots. I mean, the fidgeting doesn’t bother me.’

‘Yeah?’

‘What’s wrong with moving?’

She stares at me, her body completely still. Something about Stella’s stillness makes my fingers and toes begin to pulse with energy, so I say, ‘You know who looks restful? Dead people.’

She frowns. ‘I don’t get it.’

‘Stella, I’m just saying, why would you want to copy other people if they’re acting like a bunch of animated corpses?’

‘So you’re saying … fight the zombies?’ She looks up at the ceiling and a thin smile spreads across her face. ‘Yeah, okay.’

‘Okay what?’

‘Let’s go.’

I blink and the cloth disappears completely. ‘Sorry, where? Outside?’

‘No, to Disneyland. Yes, let’s check out the gardens at night. I mean, if you still want to?’ And she smiles at me with a flash of teeth, her eyes shining — a proper grin.

I shrug like I don’t care, but my fingers tighten like I’m trying to hold the memory in my hand.

We walk through the garden, ending up down by the Leith. She stands under the moon and shivers with cold, watching silver light wriggle like eels on the black water. ‘I’ve never come this far after dark, not alone.’

I reach down for a stone, then skim it across the river’s sparkling skin. ‘It’s different at night, especially the water.’

She nods.

‘Is that wind? In the trees?’ She listens with her whole body, and again I notice her stillness. ‘It’s like breathing … the garden’s alive, and it’s watching me. At least, that’s how it feels.’

‘Yeah, like I said, it’s different.’

Stella doesn’t answer, just nods and looks around. Above us tall trees scrub the sky with bristled hands and stars glare through the darkness. ‘Want to go climbing?’

‘Sure.’

She’s not afraid of heights. I’m amazed how quickly she slips up the trees, she’s almost faster than me. Stella pulls herself through oak branches with the lightness of a bird, scaling higher and higher until the city bursts into view. I stop to watch the lights and the ground is like a fallen sky, studded with sharp stars. But Stella keeps moving. Grinning through the leaves, she chooses the branch above me and tosses twigs onto my head.

‘Hey, watch it!’

I shoot a few up at her and she ducks, laughing.

‘Stella?’

‘Yeah?’

‘You’ve been here before?’

‘Of course. We came here for all our school holidays. I used to pretend the park was a magical house with lots of different rooms. You know, there’s so many gardens. I imagined each one had trees for walls and grass for a carpet, there was an enchanted greenhouse and fairies, stuff like that.’ She shrugs. ‘I practically grew up in this garden.’

Well, that makes two of us.

Her memory slips down, smooth and warm. She doesn’t even notice it’s gone. But the edges burn and I feel guilty for taking it.

Staring up at the sky I wonder, did we meet back then — have we both forgotten? I don’t know. But because she’s not afraid of falling, and because we climbed the same trees, I show her my collection of prize beetles, tucked in their plastic ice cream wrapper and hidden under the giant oak’s hooked roots. Stella doesn’t squeal or call them disgusting. She lets them run over her hands, but always keeps one eye on the darkness. Rabbits move through the undergrowth and even mice sound loud at night, shuffling through dead leaves. Every noise makes her blink and twist around, half expecting some mysterious danger to leap out of the bushes.

‘Don’t worry,’ I say as we slip down from the tree. ‘Nothing can hurt you.’

‘No.’ She gives an embarrassed laugh, still climbing down the trunk. ‘You’re probably the most dangerous thing here.’

But her words sounded too honest and the truth makes her stop. She sucks in a small gasp as if the idea winded her. Then Stella shakes her head and jumps, landing on the grass with a soft thud.

‘Um, Stella? You okay?’

She glances over my shoulder, staring into the gardens, taking small breaths.

‘Sure, whatever, right?’ One hand reaches up, tugging on a long black curl. ‘Seth, are we friends?’

‘I don’t know, maybe.’ I turn the idea around in my head. ‘How can you tell?’

‘You just know.’ She frowns to herself, then looks up at the sky and sighs. ‘Um, when you turn into stone is that like a spell, or what?’

She’s changing the subject? Well, okay.

‘No, the sun burns and my outsides thicken into a crust. But it’s easy to break out once the sun goes down — well, easy for me. The outer layer just crumbles like dust.’

‘You sound like Superman, pulverising rock.’

‘Who’s he?’ I wonder if she found him on the internet and my stomach twists. Anything could be on YouTube, even me if I’m not careful. Maybe it’s a good thing I threw away her phone. ‘Is Superman another troll?’

‘Definitely not. Sorry, forget I said anything.’ She turns away, looking down at the blunted grass. Above us the old oak’s branches stretch wide, their heavy ends touching the earth like we’re in a room made from crooked arms. We feel far away from her house and even the gardens, deep inside our own place.

‘How did you get here? You said you were from Scandinavia. How’d you end up living in a public garden?’

Turning my head away I stare at a silver army of trees swaying in the moonlight.

‘Well, that’s not my memory.’ I clear my throat. ‘Someone told me a story. That’s how I’ve remembered it for so long. It’s her memory, not mine. Dunno if it’s true.’

I almost mentioned Celeste, but Stella doesn’t seem to notice.

‘Tell me anyway.’ She rubs her arms and then glances at them with interest, as if just noticing the cold. ‘I’d like to hear it.’

‘Well, apparently the Victorians did a lot of exploring, capturing animals and bringing them back to England. The first zoos were inside parks.’

‘What’s that got to do with you?’

‘Over a hundred years ago I lived inside a fenced area of Regent’s Park in London.’

‘Really, how do you know?’

‘I ate the park-keeper’s memory and, um, someone filled in the rest.’

‘Oh … right.’ She leans back against the tree, blinking fast at the leaves. ‘Go on.’

I take a breath and lean forward, linking my foot around a large root which sticks out of the soil like a noose. ‘This garden has an old British design and they used to have zoos for rare animals.’

‘I know about that,’ she waves her hand, impatient. ‘My grandfather used to work here as a gardener. He showed me some old pictures in books. But there’s no way they were keeping mythical creatures.’

‘Just let me finish, okay?’ I roll my eyes. ‘Apparently some English guy had a lot of money and he travelled the world, looking for rare animals and plants to preserve in zoos. He went hunting in Scandinavia where he found us by accident. Either that or he paid the villagers to hunt us down, I don’t know. Anyway, he must’ve figured we were the last of a dying breed or something.’

‘Maybe you are.’ She watches me, frowning. ‘So, what did he do?’

‘I suppose it was clever. He was into conservation so he didn’t kill us. Instead, he put us in parks, surrounded by iron fences. See, people assumed we were statues and no one spends time in the gardens after dark. The man kept us a secret, knowing people would smash us to bits if they found out the truth. I mean, that wouldn’t fit in with the preserving part, would it?’ I shrug. ‘I don’t remember how I was sent to this park, but that’s not surprising — I forget most things, eventually. It might’ve been a mistake though, Cel — somebody told me there might’ve been too many trolls and they wanted to separate us.’

She screws up her face. ‘But wouldn’t people have heard of trolls?’

‘I guess only a few knew. Maybe they all died and we’ve been forgotten. I don’t know — I mean, who would believe in us, anyway?’

My head jerks up. I made a mistake. I said us. But Stella doesn’t seem to notice. She leans forward, hair falling over her face. Sticking one finger in her mouth, she bites the nail and says, ‘Why do you do it?’

‘Sorry?’

‘Why take people’s memories? Why not eat ordinary food?’

‘I can’t help it.’ She frowns and the edge of my stomach cramps; I know how it sounds. Don’t mind me, I’m just a compulsive, memory-gobbling monster. No biggie. Keen to explain, I decide to share one of Celeste’s theories; she must’ve heard it from someone and there’s no telling if she’s right, but it makes sense. ‘I figure we remember everything when we’re young, but our brains start to decay, just like humans. Old people forget things and so do we, after the age of about ninety. We can live without food, but not memories, otherwise we’d go crazy.’

‘Dementia for trolls?’

I shrug.

‘That’s why we’re here.’ She presses her fingers against the tree, digging into cracks between the bark. ‘My granddad’s old. Mum says it’s dementia and she’s trying to get him into a rest home, but we’re having trouble choosing the right place, waiting lists and all that.’ She sighs as small parts of the memory break away, and I say, ‘Careful.’

The taste burns, but the thought of her leaving feels worse.

She clears her throat. ‘Right.’ Running one hand over her head she says, ‘What about magic? The internet said trolls were powerful. Can’t you fly over the top of the iron gates or something?’

That’s news to me. Truth is, I don’t know much about being a troll except what I’ve been told. How reliable is Celeste? I’ve no idea, and I’ve probably forgotten bits. Bet she has, too.

I shake my head and Stella looks disappointed. ‘You’re sure you don’t have any magic?’

I shrug. ‘Well I turn into stone. Isn’t that better than pulling a rabbit out of a hat?’

And she says, ‘I was wondering … can’t you stop turning, if you wanted to stay human?’

‘No. How would I do that?’

‘I dunno.’ She bites her lip. ‘Have you considered using sun screen?’

For a second, we stare at each other. But the picture of a statue slathered in lotion makes me splutter and the sound turns into laughter, and she giggles. It’s weird, like coughing in my throat, and I wonder if I’ve ever laughed before. I hope I remember how it feels, but I probably won’t.

And then she says, ‘You know Seth, I think we’re friends.’

And I think she’s right.

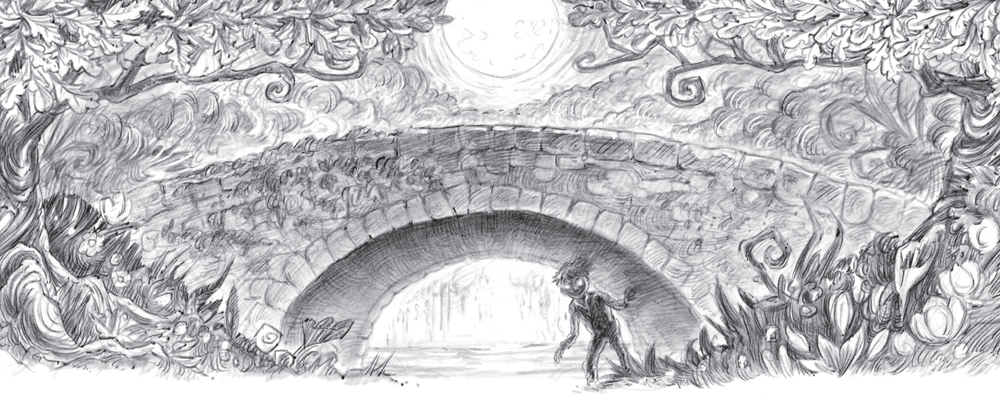

Just before dawn, I climb under my bridge. Dark-blue light makes pictures easier to see. Sometimes I forget about my drawings, but using my own bridge was smart — I’ll always find them. Of course, my memory seems to be improving, but they’re still not perfect and checking my concrete album helps …

What’s that?

A new carving.

Celeste’s face stares at me, scraped into rock. She’s wild-eyed and glaring, arms outstretched and clawing; she seems to be running right at me. A new drawing? When did I do this?

I run shaking fingers across the smooth stone, feeling the deep grooves. No, this can’t be right. They’re deeper than my other pictures; someone used a lot of force, someone stronger than me. The features look clearer, more finished than my other drawings.

My heart slams into my ribs.

Did Celeste leave me a message?

Who else would draw a running statue? Only Celeste. But entering my territory would’ve cost her, so why take the risk?

I know why.

Cool breezes rush under the concrete arch, biting my clothes, and my fists curl. Looking into those eyes of stone, a cold feeling spreads through my chest. Of course, it’s a warning.

Celeste knows about Stella, and she isn’t happy.