14

“SAY ‘cheese.’”

Kristin pointed a tiny camera toward Max. The camera sat on a small reception desk at the Icelandic Museum of Unusual Phenomena, which was a grand name for a modest, slightly sagging two-story house on a residential block.

“American or Swiss?” Max said.

Kristin took the photo, which instantly generated a security sticker for Max. “Now you, Alex.”

“Are you serious—do you really need this level of security?” Alex asked.

Kristin sighed. “We had a spate of fossil thefts in 1997, and ever since then my uncle has required photo ID of every visitor. He’ll become cross if he doesn’t see you wearing it on a lanyard. Come on—‘cheese!’”

With a sigh, Alex posed. “Cheese,” she said. “Should we call Brandon before we go in?”

Max looked out the window into the dark street. “I think he’s down for the night at the hotel. He didn’t seem interested.”

“He’s stuck in Iceland just like us,” Alex said. “We need to involve him. Four brains are better than three.”

“Unless eating whale meat decays your brain function,” Max said.

With their IDs hanging from their necks, he and Alex followed Kristin through the doors of a dark, stuffy library lined with wooden shelves that were crammed full of dust-covered books. It had a sweet-sour smell of old paper, pipe tobacco, and deep thoughts. Sitting by the window on a worn leather armchair was an old man who seemed to be part of the furniture himself. His head sagged alarmingly low, as if it had detached from his neck and planted itself on the slope of his ample belly. Slowly turning his head, he stared at Max and Alex with blue eyes so faint they had barely any color at all.

“Max, Alex, this is my great-uncle, Dr. Gunther Zax-Ericksson,” Kristin said.

He extended a shaky hand to Max. “You are the Australians?” the old man asked.

“No, Uncle!” Kristin said in a loud voice, leaning close to him. “These are Max Tilt and his cousin Alex Verne. You have never met them. They have just arrived in Reykjavík from the United States. They are trying to reach—”

“No need to yell, Katrin,” he said.

“Kristin,” Kristin said, pulling two copies of Jules Verne’s message from a wireless printer. “Katrin was your poodle.”

“And where has that infernal pet gone off to?” the old man demanded.

“She passed away, Uncle,” Kristin replied.

“What?” he thundered. “No one told me!”

“It was six years ago,” Kristin said. “She was very old. We buried her together.”

The conversation was not giving Max confidence. He glanced toward Alex, who looked away, trying not to laugh.

Kristin took a leather-bound book from Zax-Ericksson’s shelf, then pulled up a seat next to him. Setting the book and the note in his lap, she said, “Max and Alex are ancestors of Jules Verne, you know. They have found a note that he left. They believe it tells something about his motivations for the journey to Snaefellsjökull. I made two copies, one for us and one for you.”

“Ah, Verne! I’ve been talking about him lately. Such vision. Genius! Saw the future like no one besides—”

“Besides DaVinci, yes, we know,” Kristin said, gently placing glasses on his face. Then she held his copy of the note close to him, pointing to places on it as she spoke. “The top of this note here is in Braille, which they have transcribed. Would you mind reading from down here, at this spot where the Braille seems to end?”

The old man fell absolutely silent. His shaking subsided. The sad, blank look vanished from his face, and even his eyes seemed to grow darker with the concentration.

“Are they Icelandic runes?” Max asked.

“In a manner of speaking, yes . . .” he replied absentmindedly. “Would you bring me my lap desk, Kristin? And while she is doing that, come closer and tell me how you found this, children who are not from Australia?”

Alex and Max knelt beside him. Carefully, slowly, Alex explained everything—the hidden notes, the voyages, the connections to Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and Around the World in 80 Days, the suspicions about Snaefellsjökull and Journey to the Center of the Earth. And finally, the emergency that someone else was after the same secret.

Although the old man couldn’t lift his head quite vertically, he stared at her above the top of his glasses. When Alex was finished, she took a deep breath. “That’s why we’re here, sir. We’d like to trace his steps, to find out why he took his healing serum into the volcano.”

“Yes . . .” Zax-Ericksson’s eyes darted from Max to Alex with great alertness, as if seeing them for the first time. “You are the children who found the treasure in Greenland! I saw you on the news.”

“Bingo,” Alex replied.

“Yeah, we’re famous,” Max said.

“You’ve had great success with these missives from Verne all on your own, haven’t you?” the old man remarked.

“Sometimes Verne tells you everything you need to know in the first message,” Max added. “But sometimes he lets it out a little at a time. He guides you, step by step.”

Now Kristin placed a portable padded desk on the old man’s lap. “Thank you, my kind niece,” Zax-Ericksson said. “I must say, I am relieved. For a moment I thought these two might be just a couple of the typical crazies who come here. You know, Hollow Earthers, Hobnagian theorists . . .”

“Who?” Max said.

But Zax-Ericksson was pulling a pad of paper and a pen from a compartment in the desk. “Excuse me for a few moments, I must analyze this.”

Kristin led Max and Alex out of the library and into a thickly carpeted side room of the museum, just off the library. The walls were lined with old glass specimen cases and small dioramas. Each was labeled with cards that looked as if they’d been printed in the nineteenth century. In the center was a display of bone fragments, each labeled from A to T.

“These fossils were brought back by Jules and Gaston Verne,” Kristin said. “Most seem to be skull bones, some perhaps from Ice Age mastodons, others are thought to be human.”

Max leaned over them, looking closely. “Some of these are missing.”

“Six, to be exact, all stolen,” Kristin said. “The bones corresponded to six of those letters—H, O, B, N, A, and G. Apparently, if you arrange them, you form what appears to be an extremely odd head. It has the thick, armored skull of a pachycephalosaurus, an oval-shaped face, and humanlike features.”

“So . . . those six bones are definitely from the same species?” Max asked.

Kristin laughed. “Well, there is no way to know that, of course. But the letters took on a mystical property in the minds of some, and the planet Hobnag was born. People who are determined to believe nonsense are not stopped by little impediments like facts!”

“Yup,” Max said. “I’m a fact fanatic.”

Kristin smiled at him, adjusting her glasses. “I gathered. I am too.”

From the library, Zax-Ericksson’s crackly voice sang out, “Aha! I knew it!”

Kristin turned. “What is it, Uncle?”

She, Max, and Alex scurried back into the library. The old man was hunched over the lap desk. He was shaking again, but this time it looked like excitement. “Give me your copy of the Verne note, Kristin! Put it on top of my own.”

As she did, he circled a portion of it. The three gathered around and stared over his shoulder. “This, children, this! Do you see what I circled here?”

“Cave drawings?” Alex said.

“I see the word ice on the right,” Max added. “And maybe a lobster.”

“Is it futhark, Uncle?” Kristin said.

“Not exactly, my dear,” Zax-Ericksson said. “Although there appears to be plenty of that underneath, which we shall get to also.”

“What’s a futhark?” Max asked.

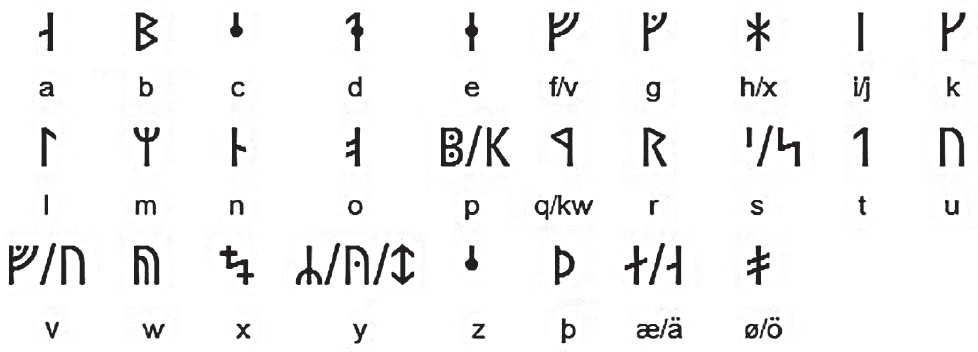

“It’s the name we give the Scandinavian system of runic writing,” Zax-Ericksson replied. “You see, runes were our form of written communication from about AD 150 until the Latin alphabet was adopted almost a thousand years later. The name comes from the first six letters, which make roughly the sound of F, U, TH, A, R, and K.”

Kristin pulled a book from a shelf, opened it, and placed it on the desk, covering Zax-Ericksson’s notes. “It looks something like this.”

“You’ll notice there are no horizontal markings,” the old man said. “This is because they were usually carved into wood. The letters are mainly formed from vertical, diagonal, curved lines. Vertical markings went directly across the grain of the wood. So if you carved horizontally, you would be carving along the grain—”

“And it wouldn’t show as well!” Max blurted out.

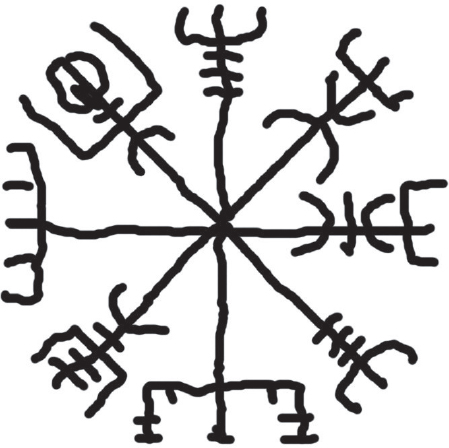

“Bravo, my boy—also, you ran the risk of splitting the wood.” The old man reached under the book. Pulling out Kristin’s printout, he set it down on the cover and gestured to the section he had circled. “But what you have here—this is something different. It is a more ancient form of runic writing. You see, it took many years for this system of individual letters to evolve. Most alphabets began as series of drawings, and Scandinavian runes were no exception. What did these drawings mean? Well, many scholars believe they were meant to have magical powers—warding off evil, controlling weather, protecting humans against misfortune. They were talismans.”

“This section you circled,” Max said. “Is it a talisman or a futhark?”

“Kristin, would you remove this book?” Zax-Ericksson asked, craning his neck toward his niece.

She took the book away, revealing the old man’s copy of the note. He had altered it, in his shaky handwriting. “You see,” he said, “I filled in the gaps.”

“Sweet,” Max said. “What does it mean?”

“That does not look like futhark,” Kristin said.

“Is it some kind of map?” Alex asked.

Zax-Ericksson began to whimper softly, and it took Max a moment to realize he was laughing. “Young man, your great-great-grandfather thought of everything!”

“Actually, it’s three greats,” Max said.

“It’s Vegvísir,” the old man said. “Just as I suspected. One of the most powerful talismans of the ancients.”

Max and Alex both looked at Kristin for an explanation, but she shrugged. “What did it do?” Alex asked.

“Veg became the word we know in English as ‘way.’ Vísir will be familiar as—”

“‘Vizier’!” Max blurted. “Like the evil Jafar in Aladdin!”

“Different root,” Zax-Ericksson said. “Vísir became ‘visor.’ It means ‘face.’ While wearing this talisman, you will always face the true path.”

The old man leaned over toward his desk and pulled open a flat drawer near the desktop. Rummaging around in some pens and pencils, he pulled out a chain that held a white charm. “Ah, here it is, a scrimshaw Vegvísir, made for me by a student many years ago. Carved from a shark tooth, most likely illegal now.”

As he held it up, the shape of the talisman twirled in the light of the office. “Can I hold it?” Max asked.

“You may take it with you, children. If it has the power it’s rumored to have, you will never be lost.” The old man let out a small giggle, looking up at Alex and then Max over the top of his glasses. “Or so they say.”