7

“IT’S kind of worn out,” Rod said.

“It’s solvable,” Max pointed out.

“It’s French.” Alex groaned.

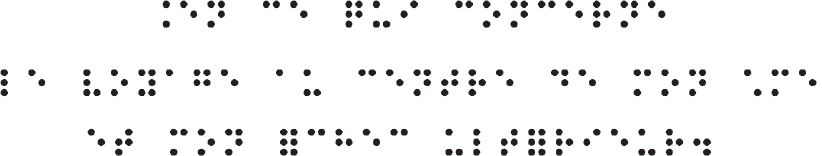

The first Braille screenshot glowed from Rod’s iPad:

“How can you tell it’s French without translating it?” Max said.

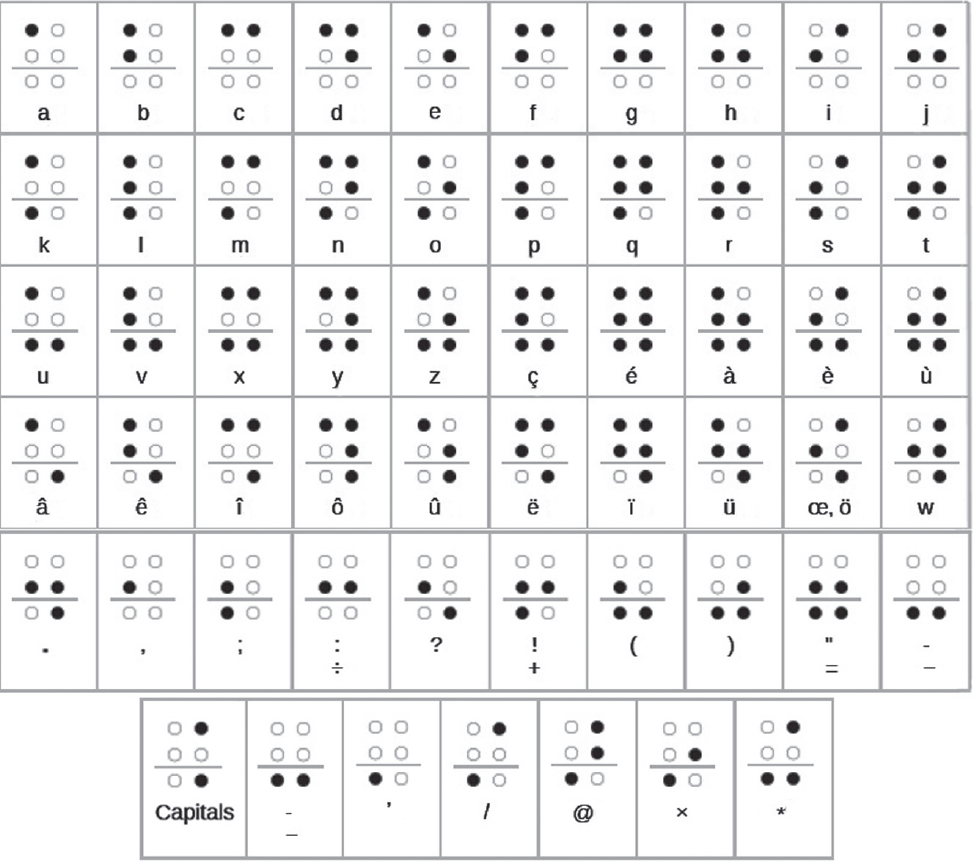

The sun was setting, and outside Rod’s dorm room window, groups of kids were throwing Frisbees. Alex looked up wearily from Rod’s laptop, where she was doing online Braille research. “You can tell by the first character—see those two dots that are stacked like a colon? In English Braille, it means decimal point. In French Braille, it’s a way of saying that the next letter is a capital. And Jules Verne definitely begins his sentences with capital letters. Because that’s the kind of guy he is.”

“Definitely,” Rod said. “But I’m looking at the Braille alphabet, and it looks like that first character is a K. One dot over the other.”

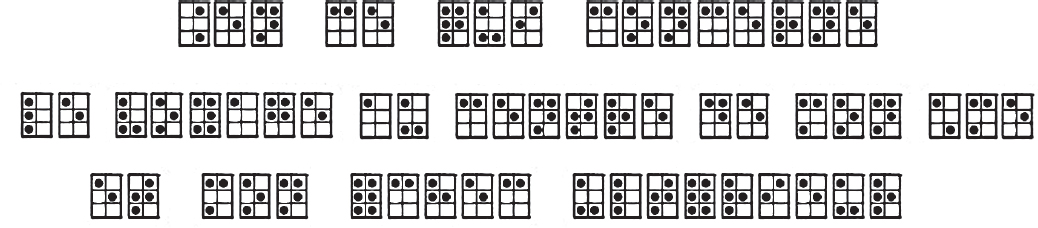

“You have to imagine that each character is in a grid,” Alex said. “I’ll show you. This program lets me toggle the imaginary grid. It puts boxes around each dot, so you can see how they’re positioned in relation to one another.”

“So look at the first character in that message,” Alex continued, her fingers clicking on the keys. “The boxes show you where the two dots are positioned. Now check out the K in the French Braille alphabet.”

“The K is two dots, but the dots are stacked on the left. In Verne’s message, the two dots are stacked on the right—and that’s sort of like a code. It indicates ‘the following letter is a capital.’ Is that right?” Max said.

“Exactly,” Alex said. “So, the top part of the message is pretty clear. But it gets worse as you descend. Parts of it have flaked off and decayed. So we’ll do the best we can.”

Together, Max, Alex, and Rod transcribed the top lines of Jules Verne’s message, letter by letter:

En ce qui concerne

le voyage au centre de mon âme

et mon échec ultérieur

“What the heck does that mean?” Max asked.

“‘Concerning the voyage to the center of my soul,’” Alex read, “‘and my ultimate failure.’”

“That doesn’t sound promising,” Rod said.

“There’s a lot more,” Alex reminded him. “If it’s anything like the first two books, Verne is going to tell us where to go. He won’t be clear about it. He’ll make us figure it out. But if you give me some quiet, I’ll do the best I can. It’s really degraded.”

Max began pacing. It was not easy to smell cat pee and mint at the same time, but that’s what happened when he was both scared and excited. “Do you think Bitsy knows about this message?” he asked. “Or Spencer Niemand?”

“If they do,” Alex said, “we’re in trouble.”

“Guys, there had to be a reason this Bitsy sprang her dad from jail,” Rod said. “Would she have done that if they didn’t know where to go?”

“No, no, and no,” Max said. “How could they possibly know? We’re the ones with the portrait. It’s been in the attic for ages. So that means we’re also the only ones with the info.”

Alex looked up from her work. “Unless they got the info from another source?”

“Or maybe they’re coming after you for your info,” Rod suggested.

“If that were true, then why would Bitsy have stolen from us?” Max asked. “We trusted her. She could have just hung with us until we all figured out what to do.”

“With Niemand, anything is possible,” Alex said. “I’m worried she’ll do whatever crazy, irrational thing Niemand tells her to do.” She sighed and looked out the dorm window. “Rod, promise to keep everything we do here a secret. And if you see any old guys with skunk-striped hair, and a blonde girl with a British accent . . .”

“I’ll report them to the Harvard campus police,” Rod said.

“Somehow,” Alex said, “that does not comfort me. Now everyone be quiet and let me work. This could take all night.”