CONSTANTINE REMAINED FOR ABOUT a month in northern Italy after the marriage of Licinius and Constantia, then left for Gaul, reaching Trier by the end of May. Here, probably in August, he listened to the panegyric describing his campaign of the previous year. He would remain in the area, except possibly for a trip to Britain in 313 until the early summer of 315, campaigning against the tribes north of the Rhine. About midsummer of that year he returned to Italy, staying in Rome for a couple of months, perhaps celebrating there the dedication of the great arch commemorating his triumph over Maxentius.

The remodeling of Rome from an architectural ode to the ambitions of the departed dynast to a monument for the triumphant liberator and the very act of liberation was rapid and effective. The Rome that one sees today is redolent of Constantine’s victory—the only readily available image of Maxentius is of the drowning man on the arch. The twenty-first-century recovery of Maxentius’ imperial regalia shows too that Constantine appears to have had no interest in the physical appurtenances of his predecessor. Similarly, he had no need of Maxentius’ guard; all of his special guard units were cashiered, and the city was left without the Praetorian Guard for the first time since the reign of Augustus.

The project of revamping Rome’s physical environment fell into three parts. One was the assimilation of major Maxentian monuments in the city center for use by the new regime; a second was the redefinition of buildings and spaces previously dedicated to Maxentius’ service away from the city center; the third was the triumphal edifice known down the centuries as the Arch of Constantine. Responsibility for the first and third of these projects resided with the Senate, while Constantine himself looked after the second.

Some of the Constantinian changes to the Maxentian original were minimal. It appears that all that was added to the Basilica Nova—a project technically under senatorial control—was an apse at the north end (necessary for structural reasons). Other changes were more substantial. It was evidently Constantine who decided that the original rectilinear façade of the Temple of Romulus needed to go in favor of the current curved face. We do not know what he did with the temple of Venus and Roma—only a few of its columns remain today—but it may be significant that one of his earliest major structural undertakings at Rome was the renovation of one of the city’s oldest temples.1

As for his new projects, the most significant at this point was the large church he built over the site of the camp of Maxentius’ horse guards on the Caelian hill. The location was convenient for a number of other properties that had fallen into his hands, including one that was known as early as 313 as the House of Fausta, a grand structure capable of accommodating (as it would) an entire church council. This site, which would later be closely associated with Helena as the Sessorium, before becoming—after her death—the Church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme was associated with an entertainment complex including both an amphitheater and a circus, the outlines of which still extend along the Viale Carla Felice-Viale Castrense. Would Fausta and Helena greet their subjects in these places? The circus, perhaps significantly, extends almost to the new church that emerged in the same area, known at first as the Basilica Constantiniana, now as the Church of San Giovanni in Laterano. The bishop of Rome made it his residence. Would Helena meet him at the circus, and did her proximity to the bishop here give her the experience she needed to undertake a mission to the east in the last year of her life? San Giovanni stood directly atop the praetorium (command center) of the old camp, celebrating Constantine’s god and the victory he had brought him over his enemies. A second grand church, planted above the guards’ burial ground on the Via Labicana served a similar purpose.2 One church that he did not build, however, despite claims that were made later, was St. Peter’s on the Vatican. The ancestor of the modern basilica was built during the reign of his son, Constans.3

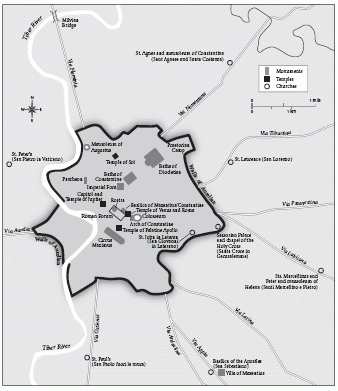

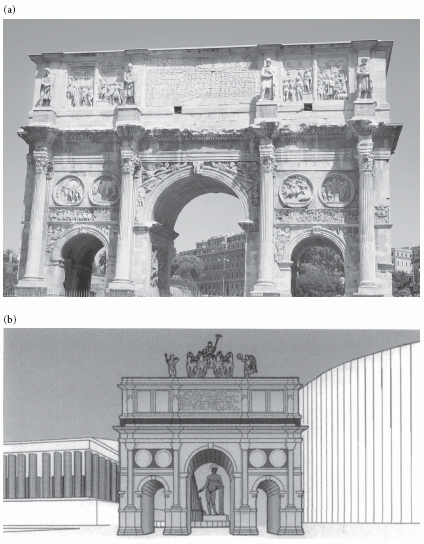

The transformation of Maxentius’ buildings and the construction of new churches were symbolic statements of victory. But it was especially and spectacularly on the arch that rose in the valley of the Colosseum that the story of that victory would be told. The location of the arch was significant. It straddled the by then traditional (if recently underutilized) triumphal route along the Via Sacra and framed the colossal statue of the Sun God, first erected by Nero (once displaying that emperor’s own features, later that of the sun god, and most recently redesigned with those of Maxentius’ son Romulus). The choice of site had been Maxentius’ and the project may have been intended to commemorate the victory in North Africa or, more probably, the repulse of Galerius. As it stands today, the arch represents the linkage of Constantine with earlier tradition and with the divine. In Constantine’s time, as you made your way up the Via Sacra from the south, you would see ahead the smiling visage of the Colossus, the head newly sculpted in Constantine’s image, emerging over the top of the arch and gazing down at the fixture that stood on top of the arch—a bronze statue of the emperor in a four-horse chariot. When you got closer, the Colossus would be fully visible through the central gateway.4

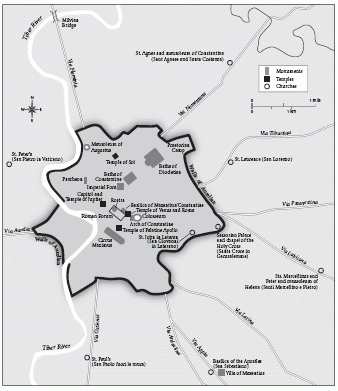

FIGURE 18.1

Plan of Constantinian Rome. After A. Tayfun Öner.

FIGURE 18.2

The arch of Constantine. As we see it now we miss the full effect that would have been provided, as this reconstruction shows, by its orientation with the great Colossus, which honored the Sun God. Source: ©Shutterstock. Reconstruction is after Marlowe (2006).

Aside from the addition of the Colossus, one of the most stunning aspects of the new arch is the reuse of sculpture from earlier periods. This practice looks back to a tradition begun under Diocletian, whose own triumphal arch, on the Via Lata, had made use of sculpture from the Julio-Claudian era; and Maxentius too had used earlier material for the tomb of his son. The arch transcends those earlier experiments, however, in the complexity of the message it creates and in the remodeling of the heads of earlier emperors to represent Constantine, Licinius, and, in one case it seems, Constantius.5

The arch presents three sculptural elements arranged in three registers. The top one comprises ten tableaux, four on the north and south faces, one each on the east and west, and set behind eight statues of defeated barbarians that once embellished a monument of Trajan. These tableaux are all taken from monuments of Marcus Aurelius and depict imperial rites and functions. On the south side the images are of the emperor “giving” a king to a barbarian people, his speech to his army, the performance of a ritual before military standards, and a display of barbarian prisoners. The north side depicts the emperor’s arrival and departure from Rome, a triumphal procession and the distribution of bounty to his people. The east and west sides show victories over barbarians. The arch’s dedicatory inscription is the central element on the north and south side.

On the central register are another four images on each side, this time taken from a monument of Hadrian. The south face shows a hunt with the emperor and his companions standing outside a gate, then sacrificing to the god of the woods, hunting a bear, and finally sacrificing to Diana, goddess of the chase. On the north side are scenes of a boar hunt, a sacrifice to Apollo, a dead lion, and a sacrifice to Hercules. The two top registers then set the actions of an emperor in their historical context, emphasizing the emperor’s courage, piety, and generosity using images closely evocative of court rituals. The third register depicts Constantine’s victory. The south face below the scenes of imperial departure shows the capture of Verona, and on the other side of the entrance, the victory at the Milvian Bridge with Constantine advancing in the company of Roma and Victoria past the drowning form of his rival. On the north side there are scenes of Constantine’s arrival in Rome; on the east side he speaks to the people of the city and on the west he distributes coins to people who approach him.

The story of the conquest continues on both the east and west faces, with a frieze showing the departure of the army from Milan beneath the setting moon, and on the east the sun rising above the triumphal entry into Rome. It is the east side that conveys the arch’s message most clearly, for here Constantine stands front and center, surrounded by his court, and at either end of the rostra (the great speaker’s platform in the heart of the Roman Forum) are shown the statues of Hadrian and Marcus that adorned it. Behind Constantine are the four columns erected in honor of Diocletian and his colleagues in 303, flanking a statue of Jupiter. The triumphal arch of Septimius Severus is visible off to the left. What we see here is the sculptural representation of Constantine’s message: the influence of Diocletian is clear, but the empire that he had labored to restore was not, in the end, of his own devising, but rather that of the Antonine age.6 Similarly, the gods depicted on the arch—the Sun and Moon, Apollo, Diana, and Silvanus—are all divinities who had little place in Diocletian’s regime; the allusion to Hercules with, it seems, Constantius offering sacrifice to him in the company of Constantine is a reference to family history. Other imperial heads were recarved in the images of Constantine and Licinius who were, at this point, still honored jointly as the liberators of the state from the foulest tyrants and the restorers of public security.7

While the visual imagery of the arch links Constantine with the great emperors of the second century, the inscription recalls Augustus the first emperor:

The Senate and People of Rome dedicated this arch, decorated with images of his triumph, to the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantine Greatest Augustus, pious and fortunate, because, at the prompting of the divinity, by the greatness of his mind, he, with his army, avenged the State upon the tyrant and his whole faction at the same instant with just arms.

The words are carefully chosen, for the phrase instinctu divinitatis (“at the prompting of the divinity”) uses strictly traditional language to describe the moment of inspiration; a Christian formulation would most likely have inspiratione divinitatis (“with the inspiration of the divinity”). This is appropriate to the illustration, for it is indeed a female divinity—in this case, Roma—who escorts Constantine into the city and draws Maxentius to his doom.8 This tallies with the version of the story in the panegyric of 313, but it is not the only allusion in these lines. Anyone who grew up in Rome would have regularly passed by the bronze tablets inscribed with the emperor Augustus’ summary of his accomplishments, placed in front of his Mausoleum on the bank of the Tiber; the opening line of that text was “At the age of nineteen I assembled an army upon my own advice and at my own expense, through which I brought forth the state [in libertatem vindicavi], oppressed by the domination of a faction into freedom.” The reference to the “faction of the tyrant” on the arch’s inscription might reasonably remind those who read it of the connection between Constantine and Augustus who had likewise rescued Rome from the tyranny of a faction to a new age. The victory with “just arms” was thus not a victory in a civil war, but in the struggle against tyranny, which transcended other forms of conflict.9

By 315, Rome had taken on a new form, and one that was distinctively Constantine’s. His victory needed to be seen as a victory for the god of Constantine, but not necessarily as a victory for the Christian god. This god could be perceived in very traditional forms or in untraditional ones. Past and present could coexist; for whatever his religion, Constantine was also emperor, and as emperor he ruled in the finest tradition of the past. Moreover, he was also very much a distant emperor in these years. Trier remained his base of operations—something that may have made relations with the senior Roman aristocrats somewhat easier since they retained some freedom of action while he was away. And it was important to keep them happy, for even as the arch celebrating the last war was taking shape, a new war was brewing.

In the summer of 316, Constantine began a slow progress down the valley of the Rhône, celebrating at Arles on August 7 the birth of his and Fausta’s first son, whose name would also be Constantine. The emperor would then be at Verona in September and in Serdica in December, and would remain in the Balkans thereafter, with but one brief journey to Italy in 318. His primary bases of operation in those years would be at Sirmium and Serdica.

The transfer of the nucleus of government from Gaul to the Balkans was the direct result of the collapse of his relationship with Licinius. This breakdown was connected with the fecundity of Fausta, who, throughout these years, was Constantine’s inseparable companion (see also figure 27.1). It also had to do with the fact that Licinius’ wife Constantia became pregnant within a year of her husband’s victory over Maximinus, giving birth to their first (and only) son in 315. Constantine immediately sought to exclude his nephew (called Licinius) from the succession by naming his brother-in-law Bassianus, the husband of his half-sister Anastasia, as Caesar with authority over Italy. Bassianus’ appeal may have been strengthened by his powerful connections, including his own brother, at Licinius’ court. Meanwhile there is some evidence to suggest tension within the ruling aristocracy in Rome, for in 315 Ceionius Rufius Volusianus ended his urban prefecture and was driven into exile by enemies within the ranks of the Senate. His fall coincided with the exile of the poet Optatianus. Both would later return in glory, which is more than could be said for Bassianus, whose influence waned as Fausta’s pregnancy waxed.10

Bassianus became the first victim of the conflict between the two imperial colleagues when Constantine accused him of conspiracy and had him executed.11 He then demanded that Licinius hand over Bassianus’ brother as an accessory to the alleged offense. Licinius, who had been on the eastern frontier—where he had alienated the people of Antioch, a city closely associated with Maximinus, by refusing to provide them with gifts—refused and set off westward. He then ordered the statues and images of Constantine destroyed at the city of Emona, an act that constituted nothing less than a declaration of war. The fact that battle was joined on October 8, 316, at Cibalae (now Vinkovci in Croatia, near Sirmium on the western end of Licinius’ domain) shows that he was heading for Constantine’s territory even as Constantine was heading toward his.12

In the months that followed, Constantine displayed both the ability that had brought him victory over Maxentius and a new overconfidence that nearly caused his destruction. We can know little about the battle of Cibalae except that Constantine was the aggressor, as had been his wont in the Italian campaign, in a battle that raged from dawn until dusk. It appears that he was visibly in command of the right wing, which finally drove back Licinius’ left wing, at which point Licinius fled and his army collapsed—or so the story goes.13 Licinius withdrew to Thrace at the eastern end of the Balkans, allegedly breaking bridges behind him to slow Constantine’s pursuit, then rallied his forces, appointing an experienced officer named Valens as his co-emperor.14 Battle was now joined at Adrianople, the vital crossroads city that was so often the scene of deadly conflict, and here again Constantine was victorious in a hard-fought battle. The tide turned in his favor when a previously detached unit showed up behind Licinius’ lines. It is a tribute to Licinius’ abilities that he was able to keep his army together, then to take advantage of Constantine’s natural aggression. From what we can tell, he probably anticipated that Constantine would press on after him toward the Hellespont, and in what remains one of the epic acts of deception in Roman military history, he now broke contact with his rival and instead of retreating east, he moved around to the west, placing his army across Constantine’s lines of communication at Augusta Traiana, the modern Stara Zagora in Bulgaria.15

Although the strategic advantage now lay with Licinius, he chose to negotiate, which may be a sign of the fear that Constantine’s unbroken string of battlefield successes instilled in him. So too may be the fact that the final terms were highly advantageous to Constantine. According to the treaty, finalized at Serdica on March 1, 317, Licinius ceded his European territories, except for Thrace, to Constantine, and agreed to execute Valens. The new Caesars confirming the principle of biological succession were appointed: Constantine’s sons Crispus and Constantine II, along with Licinius’ young son, Licinius II.16 It was thus inevitable that the descendants of Constantius would dominate the next generation.

The continuing importance of Constantius is evident in the panegyric composed by a Roman named Nazarius in 321. Although Nazarius ostensibly treats only the campaign of 312, his stress on Constantine’s sons, now Caesars, and on the role of Constantius in sending divine aid for the invasion of Italy enhances the sense of dynastic continuity. At the same time the panegyrist seems to track more closely the tale of Constantine’s relationship with Licinius than his relationship with Maxentius.17 Constantine, so Nazarius says, offered Maxentius an alliance, but Maxentius fled until it was no longer in virtue’s power to remain at peace; then how could anyone have been so foolish? How could anyone have shown more restraint than Constantine in dealing with someone of so different a kind?18 The insane tyrant of 312 has been folded into a disappointing relative who would need to be chastised.

The fact that Maxentius should be portrayed as the arch-bogeyman of recent years is all the more striking in light of the exaltation of his sister. Fausta now had coins minted with her image on them, and is styled Augusta as, most recently, had been done in the case of Galerius’ wife, who was Diocletian’s daughter. In 318–319 the mint at Thessalonica issued coins honoring both Fausta and Constantine’s mother Helena, as “the most noble woman.” In both cases, the reverses depict a laurel wreath surrounding an eight-pointed star, which has been plausibly linked with a series of consecration coins commemorating Maximian, Constantius, and Claudius II. The appearance of the two women on the coinage may thus be linked with Constantine’s claims to legitimacy through both his father and the resurrected memory of his father-in-law.19

As the stress on dynastic stability increased, the chances for peace were slowly evaporating.