CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 5

For many years I have been struggling to understand the relation between size and the division of labor in multicellular organisms. One wants to know why it is generally true that the bigger the organism, the greater the division of labor. It is a principle that to some degree we all accept as given; let us examine it closely.

The division of labor, which is a reflection of biological complexity, is a venerable subject. The history of the idea has a few years ago been admirably discussed by Camille Limoges.16 He points out that the pioneer for considering the matter within organisms goes back to Henri Milne-Edwards, who as early as 1827 said that animals had a “division of physiological labor.” Limoges goes on to say that Darwin was favorably impressed by the writings of Milne-Edwards, who in turn influenced the pioneer in sociology, Emile Durkheim. The conclusion of Limoges is that there has always been a close association between the concept of division of labor as it applies to individual organisms and as it applies to societies (a matter to which I will return). However, none of these earlier authors were particularly interested in size as a significant correlate. This tradition continues to this day, and the matter of size is not central to our current thinking. What I wish to show here is that significant increases or decreases in size during the course of evolution are accompanied by increases or decreases in the division of labor.

We now come to another of our basic size rules. The rules discussed so far are the relation between (1) size and strength, along with (2) size and surface areas. There is a similar relation between size and complexity. Like the others, it also can be expressed as an allometric relation:

(3) Complexity ∝ Weighta.

As we proceed from the strength-size rule, and particularly to the surface-size rule, there is a direct trend towards the complexity-size rule. As I pointed out before, in a larger aerobic animal it is imperative to get oxygen to the internal tissues. To do this it is necessary to produce a circulatory system with a pumping heart, innumerable capillaries, and lungs or gills with huge surfaces to trap the oxygen that is then carried by the red blood cells to the tissues. Plainly, as size increases the demands of the surface-size rule has dictated an enormous increase in complexity. The three rules are indeed connected to one another and they are all directly related to changes in size.

A convenient way to measure biological complexity is to think of it in terms of the number of cell types. A mammal will have a large number of distinct cell types, such as muscle cells, liver cells, brain cells, blood cells, and so forth. A parallel kind of list can be made for all other organisms, including plants. The number of cell types can be considered a rough reflection of the division of labor, or complexity; it is a useful indicator.

For each rule, an increase in size requires an increase, be it in strength, or in surface, or in the division of labor. On the other hand, a decrease in size generally does not necessarily require a decrease in these three properties; rather, they are simply permitted, for the smaller organism is likely to be able to manage even though it might have a surfeit of strength, or surface, or division of labor.

Estimates of the number of cell types for different size organisms have been gathered from the literature by Graham Bell and Arne Mooers.17 Their results are an excellent way of illustrating the size-complexity rule as can be seen when they are brought together in a graph (fig. 19). The larger the organism, the greater the number of cell types.

Note that despite the clear trend there is a wide scatter of the points in the figure. The variation might have a number of causes. It is very difficult to make accurate measurements of the number of cell types; all these estimates are rough. The data come from different authors who undoubtedly have differences of opinion as to what constitutes a discrete cell type.

Figure 19. A log-log graph of the number of cell types plotted against the total number of cells for a vast array of organisms from very small colonial forms to the largest animals and plants. (Redrawn from G. Bell and A. Mooers, Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 60 [1997]: 345–363)

It should be noted here that the size-complexity rule also applies during development. Both plants and animals normally begin at a single-cell stage and become increasingly multicellular with time. During this process there is a proliferation of cell types, which ultimately become adults that reach the number shown on the curve in figure 19. Since during development the organism becomes progressively larger, it would be very interesting to know how many cell types there are at each developmental size. Unfortunately, I have been unable to find any such measurements in the literature, but it is obvious that the size-complexity relation must hold. However, there is one point to remember: many of the cell types will not be functional when they first appear. For instance, all the cell types associated with digestion in the gut in an animal are passive until the first meal. Before that they are merely preparing for the passage of food. So the size-complexity rule is somewhat different during the course of development, yet the rule holds.

My plan here is to examine the size-complexity rule across a huge spectrum of sizes, from small and lowly primitive organisms to huge societies. The former are of particular interest because they give some insight into how the division of labor might have arisen in early evolution. There is no better place to examine the matter than at the origin of differentiation, where one finds closely related species with either one cell type or two. An example is found among the green alga Volvox and its relatives.

Species of Volvox are common in freshwater ponds, first described by van Leeuwenhoek in the seventeenth century using his simple microscope. It consists of a sphere of a single layer of some thousands of cells at the surface of a sphere (rather like a minute tennis ball with its hollow center) about the size of a small pinhead (fig. 20). Most of the cells have two flagella that stick outward and beat in coordinated waves so that the whole ball rotates like a globe that can spin around its axis. What concerns us here is that in Volvox there is a division of labor: most of the cells are the ones just mentioned that move the colony and are capable of photosynthesis, but there are a few cells that are reproductive and have no flagella—they develop into daughter colonies.

Figure 20. The ranges of sizes in the volvocine algae. From left to right, the ancestral single cell Chlamydomonas, the 16-cell Gonium, Eudorina, and Volvox. (Selected from W. H. Brown, The Plant Kingdom, 1935)

A number of other species of volvocine algae are smaller and are made up of fewer cells (fig. 20). The whole group has been studied in exemplary detail by David Kirk, and among many of the things he and his co-workers discovered using DNA analysis, the multicellular forms arose from a single-cell ancestor known as Chlamydomonas, as had been suspected before based on morphological grounds.18 Another interesting bit of information has come out of Kirk’s DNA analysis of the ancestral tree of the volvocine algae. The old, conventional idea that they evolved by a simple, linear progression from small to large has been shown to be false. There is indeed an obvious span of sizes from the unicellular Chlamydomonas to the largest species of Volvox, which may consist of 50,000 or more cells (fig. 20). However, the history of the group is more complicated than was previously believed. Volvox itself has arisen independently more than once during the course of evolution. Even more relevant to this discussion, it appears that certain species of Volvox are ancestral to smaller forms, such as Pleodorina, as well as the reverse. So there apparently have been evolutionary decreases as well as increases in size during volvocine evolution.

Here I want to focus on the two cell types that are present in the asexual life cycle of Volvox. The biflagellate, nonreproductive (somatic) cells are responsible for the movement of the colony, and the reproductive cells (gonidia) produce daughter colonies. The former are terminally differentiated and are incapable of dividing, while the latter become cell-division specialists and are incapable of locomotion.

There is another important bit of information concerning this dichotomy. We know that very few genes are involved in this transition from one to two cell types. The initial discovery was the mutation of one gene that would transform a normal Volvox so that all the cells that would be somatic became reproductive and divided very rapidly, producing thousands of minicolonies in one large individual, similar to what occurs in small volvocine species. Subsequently, it was discovered that a few other genes were involved, but clearly the invention of this division of labor appears to involve only a small number of genetic steps.

This two-cell-type state is correlated with size. At one end of the size range, Volvox, which contains thousands of cells, always has both cell types. At the other end of the spectrum, Gonium, which never has more than 16 cells, has no division of labor: all Gonium cells are initially biflagellate and involved in locomotion, but later all of them shed their flagella and undergo reproduction by successive divisions to produce daughter colonies.

There is a particularly interesting feature concerning the invention of the division of labor among the volvocines. Some species can exist in different sizes, and only the larger forms will have more of the two cell types. They apparently can asses their size: the larger they are, the greater the division of labor. This ability is known as quorum sensing.

Eudorina can have either 16 or 32 cells, depending on environmental conditions. In the 16-cell colonies, like Gonium, all of the cells participate first in motility and then subsequently in reproduction. However, in 32-cell colonies, the four cells at the anterior end of the colony often remain terminally differentiated nonreproductive cells that continue beating their flagella, while the other 28 cells reproduce. In another genus, Pleodorina, which always has a division of labor, the ratio of nonreproductive cells to reproductive cells increases as the total cell number is increased. In colonies with 32 cells, 25 percent of the cells are sterile nonreproductive cells, while 50 percent of the cells are so in colonies of 128 cells. Clearly, within this critical intermediate size range the proportions of the two cell types varies depending on the size of the colony.

A central question is what selective advantage might volvocine algae have gained by producing terminally differentiated somatic cells that are incapable of reproduction. It might be simply that this dichotomy enables them to reproduce while simultaneously swimming and gaining energy through photosynthesis. If it is a small species that has only one cell type, in its nonmotile reproductive phase it will sink to the dark bottom of the pond where photosynthesis would be impossible. In Eudorina and Pleodorina we see an intermediate situation: in the larger forms there is an increase in ability to carry on photosynthesis while reproducing. This is the basis for suggesting a quorum-sensing mechanism where a group of cells take into account their number so that they behave differently when they are large as compared to small. It means that in these instances there must be a genetic mechanism for setting apart the two cell lineages, a system that is not rigid but plastic and capable of responding to size. It is puzzling to imagine in this case what the selective advantage of quorum sensing might be; perhaps there is none and it is simply a byproduct of the genetic activity.

The cellular slime molds provide another interesting example of the borderline between one cell type and two. They have an unconventional life cycle in that the separate amoebae eat bacteria in the soil, and upon starvation they aggregate to form a multicellular individual that ultimately produces a small fruiting body: a mass of encapsulated spores held up by a delicate stalk. Unlike most other organisms, they feed first and then become multicellular. Most species of slime molds have two cell types: spores and stalk cells. The exceptions are the species of Acytostelium that make only spores; their stalk consists of a delicate strand of cellulose extruded by all the cells before they become encapsulated into spores (fig. 21). From some work directed by S. Baldauf and P. Schaap using DNA methods to build a slime mold ancestral tree, we now know that Dictyostelium discoideum (including some of the other common Dictyostelium species) and Acytostelium are far removed from one another and only distantly related.19 So, unlike what we saw in the volvocine algae, the two genera of slime molds did not go back and forth in size during their evolution.

Nevertheless, the different species of Dictyostelium that have two cell types are in general larger than Acytostelium that has no stalk cells and therefore only one cell type. There is a separation between the smaller species with one cell type and the larger ones with two. In these organisms, size is not determined by multicellular growth, as it is in most organisms including Volvox, but by the number of amoebae that enter an aggregate. Therefore, this size-complexity relation holds regardless of how size increase occurs. Despite this difference, both the volvocine algae and the cellular slime molds are similar in having a size threshold for the number of cell types.

Quorum sensing is also found in one species of cellular slime mold; the case of Dictyostelium lacteum is particularly interesting. When very small fruiting bodies arise, a partially acellular stalk is produced;20 it is as though there is a threshold concentration of a key substance or substances that stimulate a cellular stalk, but if there are very few cells, the concentration is insufficient to be wholly effective in producing a stalk with cells (fig. 22).

Figure 21. A diagrammatic comparison of a rising fruiting body of Acytostelium with only one cell type (left) and Dictyostelium with two—the dark spores and the stalk and prestalk cells (right). A particularly small Dictyostelium is drawn so that the cell structure of the two can be compared. (From Bonner, The Evolution of Complexity, 1988)

Figure 22. A very small fruiting body of Dictyostelium lacteum showing an acellular tip. (From Bonner and Dodd, Biol. Bull. 122 1[1962]: 13–24)

Why is there quorum sensing involving the division of labor? It might be adaptive, for it reduces the cost of construction in those forms that are of intermediate size. In the case of D. lacteum, for instance, if a cellular stalk is not needed for support, then, by making part of the stalk acellular, a few extra spores are produced. In larger species, very small fruiting bodies can be produced in which the stalk is cellular; the smallest one known is a fruiting body of one species (P. pallidum), made up of three stalk cells and four spores. In other words, quorum sensing is not universal and not found in larger species but only in one species near the borderline between large and small.

A final example of going from one to two cell types may be seen in the filamentous cyanobacteria, known to be very ancient organisms. In many species, besides spores they have two vegetative cell types: the photosynthetic cells and the heterocysts that fix nitrogen (fig. 23). The two activities cannot be carried on in the same cell because the enzymes that are responsible for the incorporation of nitrogen cannot function in the presence of oxygen, which is produced by photosynthesis. Nitrogen is essential for all living cells for many key substances that contain nitrogen, such as proteins and nucleic acids and many others. With heterocysts, both of the essential biochemical activities can occur at the same time.

Not all species have heterocysts: some have a temporal separation of the two activities, a temporal division of labor. All the cells photosynthesize during the day and fix nitrogen at night.

In cyanobacteria, the ratio of vegetative cells to heterocysts remains constant regardless of the length of the filaments. The important size constant is the physiologically functional units; they are modules. This is a form of quorum sensing, for a heterocyst senses the number of neighboring vegetative cells, and a proportion is retained in each module. In this case, the selective advantage is obvious: to produce a balance between photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation.

Figure 23. A cyanobacterium filament showing evenly spaced heterocysts. (From G. M. Smith, The Freshwater Algae of the United States, 1933)

Quorum sensing is a newly recognized phenomenon that has become an exciting field of research in microbiology. The idea is that when cells come together, a critical number is required to be able to perform activities that would not be possible if there were fewer cells. I have already described a somewhat similar phenomenon in the wolf-pack feeding of myxobacteria, where feeding can be effectively achieved only if large swarms of cells exist; only then can they produce enough extracellular enzyme to effectively digest external food. Bonnie Bassler made the key discovery that luminescent bacteria are only capable of giving off light if they are present in a critical mass—when that number is attained, the light goes on.21 This has turned out to be of great importance in medicine because the same situation is found among pathogenic bacteria that can only produce their undesirable effects when they are present in sufficient numbers: a quorum is needed before they can do their damage.

Both the volvocine algae and the cellular slime molds provide good examples of size quorum sensing. In each case they occur in species that are intermediate in the size range, and the individuals of those species can vary in size. If the individuals are large they will have two cell types, if small only one. They can sense their size and provide and respond accordingly when they are above or below a certain threshold.

In all the cases we have discussed with one or two cell types, including those cases of quorum sensing, it is evident that size is tightly correlated with—and very likely the direct cause of—the number of cell types, and not the reverse. Changing the number of cell types does not dictate the size of the colony or group—it is the size that dictates the number of cell types.

The lesson to be gained from this kind of quorum sensing is that there can be a tight control between size and the number of cell types. If we now turn to larger organisms with many cell types, we find a somewhat more general correlation, but nevertheless the size-complexity rule holds. We have already seen that when there has been a size increase during the course of evolution, it has often been accompanied by an increase in the number of cell types, but even more revealing in providing evidence that a change in size can result in a change in the division of labor are those cases where there has been a decrease in size and a corresponding decrease in the number of cell types. Here an example will be given for animals and another for plants.

Rotifers are very small animals that live in ponds and lakes and other wet places (see the rotifer in fig. 6). They feed on small unicellular forms, especially bacteria. The majority of rotifers have a conventional gut tube, while others have a central part of their body into which food vacuoles are formed at one end and excreted at the other, very similar to the digestive system found in ciliate protozoa (fig. 24). The no-lumen rotifers lack a cellular stomach and on this basis are considered to have fewer cell types.

Figure 24. A diagrammatic view of the gut of a species of rotifer, one with a lumen (left), and one without a lumen (right). (From T. A. McMahon and J. T. Bonner, On Size and Life, 1983)

In the past it has been my assumption that their ciliate-like digestive system is related to small size. This was just asserted; is it possible to find any evidence for the assertion? Fortunately, Josef Donner in his exhaustive monograph of the Bdelloid rotifers gives the length of large numbers of species,22 and I have extracted this information for forty-eight species without lumen and seventy-four with. It is clear that the mean lengths of the former are significantly smaller than the latter, and the assertion is justified.

However, the overlap is considerable: some species without a lumen are larger than the smaller ones that have one. This raises the question of which anatomy came first during the course of evolution. At the moment there is no molecular ancestral tree evidence, but it would be reasonable to assume that the gut with a lumen is ancestral and that there has been a subsequent size reduction in some species. If this were so, it would be another example of size affecting the number of cell types. The fact that there is not a perfect correlation between size and the degree of cell differentiation is another indication that the rule is approximate.

A parallel example can be given for plants. Ordinary angiosperms are estimated to have up to forty or more cell types while the two small duckweeds have far fewer: Lemna has eighteen and the minute Wolfia about eight (fig. 25). There is little doubt that these smaller forms are descendants of larger ancestors and that there has been a reduction in the number of cell types accompanying the size decrease. The key question is, why are there fewer cell types? The most obvious explanation is that there has been a selection for size decrease, and that mechanically all the ancestral cell types are neither needed, nor is there room for them in the small body. Again, the size and division-of-labor rule is followed among higher plants, albeit again in an approximate way.

Figure 25. Two species of duckweed that are the smallest flowering plants. Floating on the surface of water, the minute Wolffia (about 1 mm long) surrounds the larger Lemna. (Drawing by Hannah Bonner)

Let us turn now to the matter of the effect of size increase on complexity. As I pointed out earlier, from the evolutionary point of view we know that the maximum size of both animals and plants has increased progressively over geological time (fig. 17) and we can now say that this also must be true for the number of cell types. This is because, as we have just seen, with size increase there is a corresponding increase in the division of labor. In fact, James Valentine and his colleagues have plotted the maximum number of cell types on an evolutionary timescale and show that they rise with time in the same manner as size (Fig. 26).23

The relation between size and the number of cell types being approximate, one may ask what sets the upper and lower limits of the size range for organisms with a particular number of cell types. If, in the selection for size changes, an animal or a plant becomes too big or too small to be physiologically efficient and be able to compete effectively, it will become extinct. The range of size among mammals is extensive—from mice and shrews to elephants and whales—yet each in its own environment can successfully exist, and they do not differ to any great extent in their number of cell types. This great span of sizes of similarly built and physiologically efficient animals has taken millions of years to achieve—each step requires adjustments for stability.

Figure 26. Estimated numbers of cell types of early members of various animal groups. Only members of the groups that are believed to have been rather near the upper limit of cell type numbers when they originated are included. (From Valentine, et al., Paleobiology 20 [1994]: 131–142)

A large size span can, however, be achieved very quickly through artificial selection. Consider dogs, from the miniature Chihuahua to a huge Great Dane. Here it is unlikely that there is any difference in the number of their cell types, and the change in size has taken mere thousands of years, beginning with the domestication of the wolf (fig. 27). However, this is not natural selection but artificial selection and breeds with less successful physiological constitutions like the larger breeds of dogs have a significantly shorter life span than smaller ones.

Figure 27. Showing the span of the sizes of dogs, the result of artificial selection for size from the ancestral wolf. A large Great Dane alongside a small Chihuahua. (Drawing by Hannah Bonner)

This leads to an important point that has always puzzled me. Why do mammals with the same number of cell types have a huge size range? The answer comes from an important insight of Megan McCarthy and Brian Enquist, who show that it has to do with their levels of metabolism.24 Size is not the only factor to influence the number of cell types, but metabolic energy is an additional key factor that correlates with cell type numbers. The metabolic rate of a mouse is much greater than that of an elephant, and for this reason it also supports a large number of cell types. A related question is, why do animals have more cell types for a given size than plants? The reason is the same: plants have a much lower metabolic rate than animals. In the next chapter I will return to this relation of metabolism to size.

The whole idea that there is a relation between size and the division of labor was first realized in human societies. It is an ancient principle that we associate with the eighteenthcentury economist Adam Smith. The larger a nation or a community, the greater the division of labor, often expressed in terms of an increase in specialized trades or occupations. In a small village, individuals have to be jacks-of-all-trades, while in larger communities there is a cobbler, a butcher, a smith, a tailor, and so forth. In even larger cities or towns, there is a further division of labor where we find lawyers, bankers, policemen, doctors, and many other specialized occupations. Even institutions as they increase in size will divide the labor: large businesses will have a whole hierarchy of managers; large universities will have layers of administrators and teaching faculty; an army has a multitude of officers and enlisted men of different ranks, and so forth. The rule clearly holds for human societies, and there are a few examples where measurements have been made (fig. 28a, b).

The rule also applies to insect societies, which are quite remarkable for their size and diversity. Some ant colonies will have one queen with millions of workers attending to all the activities and functions of the nest, such as feeding and caring for the young, foraging for food, and protecting the colony. At the other end of the spectrum there are certain primitive wasps that have very small colonies, consisting sometimes of less than a dozen individuals.

Figure 28 (facing page). Log-log graphs showing the relation of size to the division of labor for societies. (a) The number of occupations found in each of the states in India (graph of N. V. Joshi in Bonner, Current Science 64 [1993]: 459–466). (b) The number of organizational traits (specific crafts and occupations) plotted against the size of single-community societies. (Five of the latter are labeled.) (From Carniero, Southwest Journal of Anthropology 23 [1967]: 234–243)

In these simple social wasps there are no morphological differences among the females that come together to form a small colony. There is, however, a dominance hierarchy that can be seen in behavioral differences. One female will remain queen by lording it over the others, and she alone will lay eggs for the next generation: she will forcibly prevent other females from doing so. The other females do not all do the same thing: some concentrate on food gathering, others on protection of the nest, and some just loaf. In other words, these primitive social wasps do divide the labor, but only by using subtle, behavioral means of doing so.

By contrast, in large colonies of ants and termites there are morphological differences between the workers. They may not only differ in size, but in shape as well, and those shapes are associated with specific tasks within the colony. The smallest workers are primarily occupied with the care of the young, the middle-sized workers are busy foraging for food, while the largest workers, the soldiers, will guard and protect the nest. To see if one could measure the extent of this morphological division of labor in relation to the size of the colony, I took a table from B. Höldobler and E. O. Wilson’s great tome on ants, which gave the colony size for a large number of ant species.25 I broke this up into groups based on colony size, and Wilson was kind enough to tell me how many morphological castes there were for each of these species. He added that for some species this task was easy, for the castes are discrete in their shape; but for others there is a continuum, and therefore assigning a number for the different castes is difficult and subjective. I was fortunate to be able to rely on his great experience in observing ants and was able to plot colony size versus caste number to show that, as expected, there is a clear and significant increase in the number of castes with an increase in the size of the colony, despite a considerable scatter of the points (fig. 29).

Figure 29. The number of ant castes plotted against the size of the colony. The line is a regression showing a significant trend (r2 = .25). (From Bonner, Current Science 64 [1993]: 459-466)

The results for societies can be compared with similar plots for multicellular organisms (see fig. 19). In all cases the trend is highly significant. Note that societies also show a considerable scatter of points; here again the rule is a statistical correlation and not an exact one. If a village grows, there is no sharp, critical point that dictates an increase in the division of labor.

What multicellular organisms and societies have in common is the need to increase their efficiency. In organisms this is done by genetic variations subjected to natural selection; in human societies the efficiency is measured in economic success. Both involve competition, but differ in the nature of their variation. In one, the variation is inherited and culled by conventional Darwinian principles; in the other, the variation is not genetic but cultural, and it is culled by economic rather than biological efficiency.

Thus far we have examined three size rules: strength and diffusion keep pace with size increase, as does the division of labor. The latter is not only true for the number of cell types within an organism, but for the number of specialized activities in societies. The three rules are closely interrelated and show the ubiquitous importance of the role of size.

In looking at the relation between size and the division of labor, the important question is the effect they have upon each other. Natural selection will act on both size changes and the internal physiological efficiency. If there is selection for a significant increase in size, selection will in turn change the internal structure to maintain physiological efficiency, and this effect may involve an increase in the division of labor. If there is a selection for a size decrease, again the efficiency must be maintained. Usually this process does not require a decrease in the division of labor, although, as has been shown, it can occur. Going in either direction there are presumably thresholds beyond which efficiency (involving the appropriate division of labor) must change to keep pace with size.

This means that within these limits there can be changes in size without changes in complexity, and conversely changes in complexity without changes in size. Because of the latitude of change within the limits for both size and complexity, one can expect—and finds, as we have seen—large variation in the size-complexity rule.

If we now ask why human societies seem to follow the same size-division of labor principle as cells, the answer is somewhat different from that of cells. There are none of the obvious physical constraints we saw for cells; but even more important, there is a totally new element, namely behavior. Individual organisms devoid of a brain can only pass information through their genes, but in the evolution of animals there arose an entirely new method of passing information, and that is by behavioral signals between one individual and another. These signals have been called “memes” by Richard Dawkins.26 Genes can be passed on only through egg and sperm (or asexual bodies such as spores) from one generation to the next, and therefore many generations are required over a long period of time for a particular gene to spread through a population. Memes, on the other hand, can pass from one individual to another in an instant of time, and as a result can spread very rapidly through a population.

There is, of course, much more to behavior than the passing of information between individuals; for instance, we can solve problems. Animals can also solve problems, but of all animals we are undoubtedly the most skilled in doing so. It is this problem-solving ability that is the key to how the labor is divided in societies.

A good example may be found in ant societies. Their division of labor is ultimately genetically based—including their ability to respond to nutritional and environmental conditions—and therefore subject to natural selection. This is certainly true, but insects have some flexible behavior as well, and perhaps even a modest ability to solve problems. Those who work with social insects can give many examples; here is one that makes my point. If, in an ant colony where different castes perform different labors, one removes one of the castes, then some of the workers from other castes will take over the tasks that they never performed previously. In other words, they show a behavioral flexibility; in a way, this could be considered an example of minor problem solving. By being flexible they see to it that all functions, all the labors, required for the welfare of the whole colony are carried out, despite the loss of one of the castes. From this one might conclude that in social insects there can be a mixture of behavior in a background of a strong genetic basis for the division of labor.

For human beings, the genetic component takes a back seat. No doubt the structure and the abilities of our brains have a genetic basis, but what we do with our brains in terms of thoughts, including problem solving, is way beyond our genes. Our skills may have a genetic basis, but what we do with those skills opens up a new world.

Today the whole subject of division of labor has taken on a new cast for human societies. With the tremendous increase in the size of our population, standard ways of increasing that labor, such as we have been discussing, have become increasingly complicated. This is true in all ways: in commerce and in economics in general, and in government. We are in an era of world trade, of globalization, of amalgamation of businesses into mega corporations; size alone has created vast complexity, and new ways of remaining efficient are being created. This has been helped, even fueled, by the extraordinary increase in the efficiency and rapidity of our methods of communication, beginning with the telephone, the radio, television, fax, and then the extraordinary burst created by computers with all the lightning powers of e-mail and the internet. World population and these technological advances have brought us beyond the straightforward size/division-of-labor relation I have been describing. Now we are in the next phase of unimaginable complexity. It is as though we have gone from the brain of an insect to that of a human, where not only has there been an enormous increase in the number of cell types, but the sheer number of neurons and their interconnections have risen astronomically. Just as our brains are capable of doing things that an insect cannot do, and does everything in a different way, so our modern society deals with all matters that preserve efficiency in a way that is different from what we did before.

From the many examples of different magnitudes that we have examined—from two cell types to huge societies—we see that the change in size comes first, followed by the degree of the division of labor. This process is especially clear-cut when there is a size increase that directly leads to a greater division of labor. But we also saw that a decrease in size can be followed by a corresponding reduction in the number of cell types, as in rotifers and duckweed. The most compelling evidence of size being the arbiter of complexity is from the quorum sensing in volvocine algae and in cellular slime molds, where only two cell types are involved. There is either one cell type or two types, depending on a small shift in size.

We now go to a big canvas: to huge ecological communities. There we have organisms of all sizes living together and interacting with one another either in competition or in cooperation. In many ways it is similar to a community of cells that make up a multicellular organism: the component parts in each case are continually communicating and interacting with one another so that in both cases there is a collective wholeness. In one case it is within an individual multicellular organism, and in the other it is between the individual organisms in a patch of nature. One major difference is of size: individual organisms get no bigger than whales and giant sequoias, while ecological communities can spread over huge geographic areas.

It is obvious that small organisms will be more abundant than large ones—we are surrounded by evidence of this fact. The number of bacteria per square mile in the African veldt is unimaginally larger than the number of elephants.

Beginning with plants, it is well known that trees in a growing forest first are a dense thicket of saplings, but as they grow they do not all survive; there is a “die-off” or “self-thinning” of the less fortunate individuals, so that a forest or patch begins with many small young trees, and ends up with a few large ones. The same is true of crop plants if sown too close together. Clearly, as the plants grow they need greater resources, such as leaf space to catch the sun for photosynthesis and root space to gather water and minerals in the soil; they compete with one another, and as a result there are winners and losers.

The same rule applies to animals; the main difference is that animals are mobile. The spacing of animals is also governed by energy considerations and the availability of resources in the form of food. Since animals do not use the sun’s energy for nutrition but eat vegetable matter or meat, in general the consumer is larger than the consumed. Many of the larger animals, such as giraffes or moose, are plant eaters, and they certainly are larger than the salads they consume. This is true at the other end of the size scale, too: minute rotifers eat even smaller bacteria and unicellular forms. There are exceptions to this very general rule. For instance, large plants can also be consumed by small insects. And parasites have fiendish ways of attacking hosts many times their size, either by devouring them from within, such as parasitic wasps infesting huge caterpillars, or living within a large animal as a nonlethal partner, as for example our intestinal bacteria that help to process our food.

Earlier I laid down five size-related rules, and the relation between the abundance of organisms and their size was one of them. The rule can be expressed as

(4) abundance ∝ Weight-b,

which simply says the greater the size of an organism, the fewer individuals there are in a geographic area. (Note that contrary to the other rules, the slope of the line goes in the opposite direction.) This is an old subject that has been measured and treated in detail. Following the equation above, one can plot the logarithm of the density against the logarithm of the size of the organism. R. H. Peters has collected a large amount of information on animals from the literature and put it in one graph (fig. 30).27 A straight line can be drawn through all the points, although as Peters discusses there is a considerable scatter of the points, making it difficult to be certain of any general mathematical principle. The important message for us is that the size-abundance rule holds for a tremendously wide range of organisms.

Figure 30. A log-log plot of the size of animals and their abundance in nature. Solid dots are mammals; squares are birds; hollow circles are invertebrates; x’s are reptiles and amphibians. (From R. H. Peters, The Ecological Implications of Size, 1983)

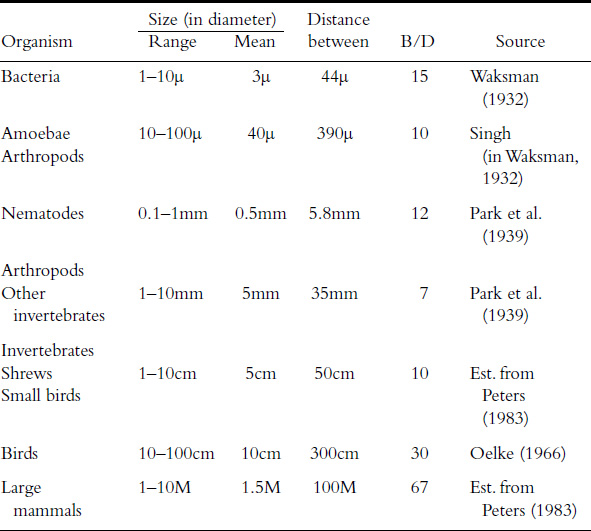

The rule can be illustrated in another way. If one divides the size of an organism (expressed in linear dimensions, such as its approximate diameter), which we will call D, by the average distance between individuals of its own kind, or B, the values for this B/D ratio will be in the same order of magnitude from bacteria to elephants.

A glance at the table shows that terrestrial organisms, over a huge size range from bacteria to large mammals—seven orders of magnitude—all have B/D values that are quite close to one another, a range from roughly 7 to 70. This means that if these organisms were evenly spaced—which they are not—then the distance between them would be more or less the same number of body diameters apart, no matter their size.

The same is undoubtedly true for plants, as one would expect from their “die-off.” To give an example, my colleague Henry Horn has measured the trunk diameters and the distance between trees in five different woodland areas, and the B/D values are all within the same range as those of the animals.

Measuring the ratio of the distance between organisms and their linear size and finding that it is roughly constant over a great range of sizes is no more than another way of illustrating the size-abundance rule. Note that since both measurements are distance, that is, linear, the B/D ratio is a dimensionless number.

By dividing the distance between organisms (B) and their diameter (D) it can be seen that over a size span of 7 orders of magnitude the ratio is moderately constant.