Much has happened since the great writer and chef (to use a current term) Emilia Pardo Bazán bequeathed to us these prescient words, which perhaps we now understand better than ever: ‘Every era of history modifies the stove, and every nation eats according to its soul, perhaps before its stomach.’ This I believe may be relevant to the topic at hand, which is none other than form in cookery and its varied expression throughout history. Of course, this does not devalue one iota the importance of flavour and taste as the basis of good cooking, both in the past and now. Form cannot mask the real taste of what we eat. But it can turn a necessary act, a sometimes daily routine, such as mere nutrition, into a celebration of the senses. And the sense of sight is not the least important. Hence, we have created a number of recipes, within the margin of their indispensable palatability, to enhance the aspect of various kinds of form. Firstly we have, trompe l’oeil (performed in multiple cuisines in the world) to reflect a complex world of appearance and reality, impact and mystery, also very present in the seventh art, cinema, and of course, in painting and even architecture.

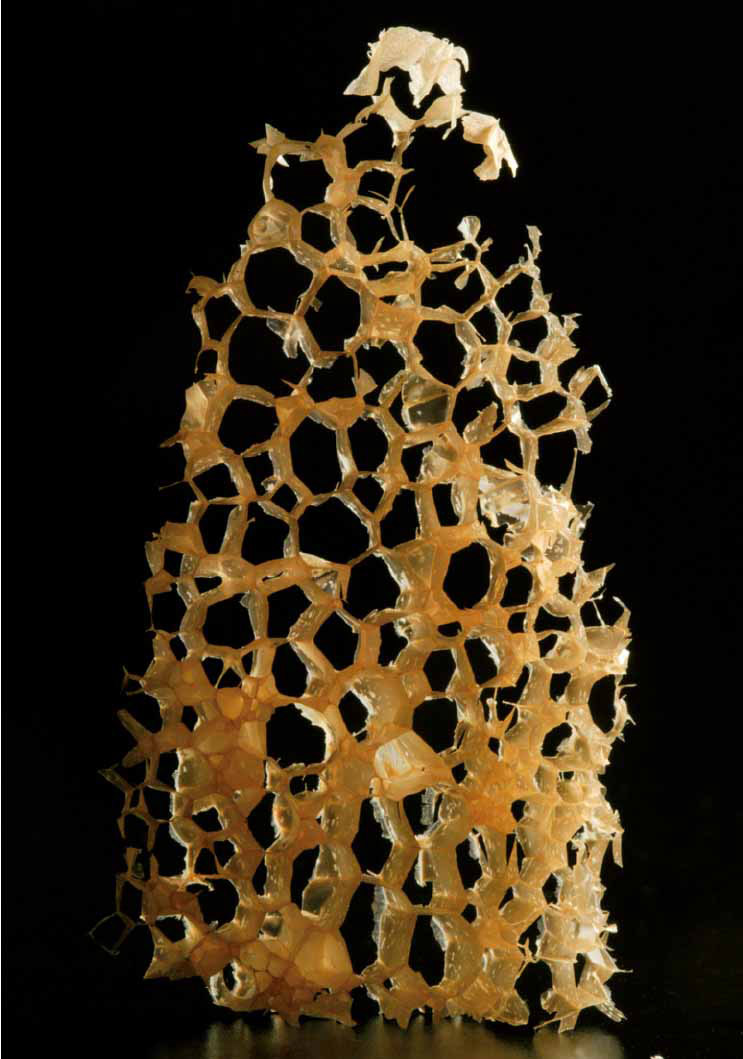

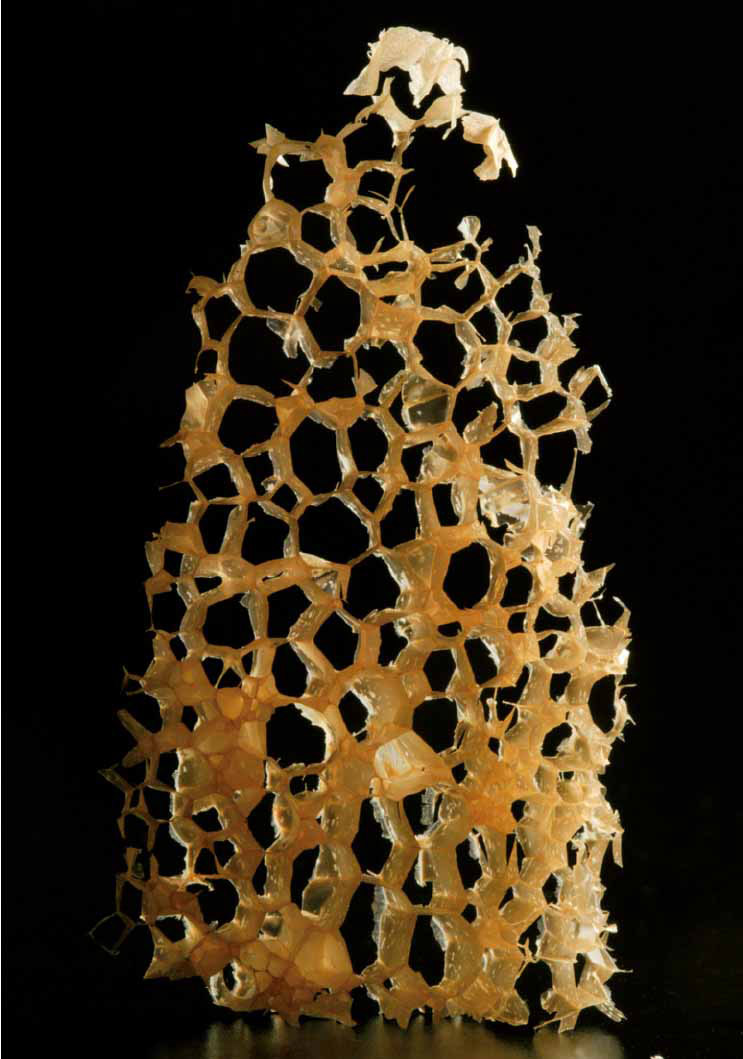

As its name suggests, the trompe-l’oeil – from the French – is nothing more than a trap for the eye, and the Spanish Royal Academy of language defines it as: ‘ A trap or illusion that deludes someone into seeing what is not.’ In any case, it is a deception that always consists of a tasty and even complicit form. Because we already know that ‘Pumice Stone’, ‘Sardine Fossil’ or ‘Foie Gras Totem’ or ‘The Moonstone’ are the fruits of a chef’s imagination, identifying his creative works with forms that originate in these statements and are reasonably similar to the real world.

The fractal theme needs an explanation, even though it is very elementary and succinct...

Science or, in this case mathematics, can be integrated into food in a natural form, as is the case with fractal food.

A fractal is a semi-geometric object whose basic structure, fragmented or irregular, is repeated in different scales. The term was invented not long ago, in 1975, by the mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot, and derives from the Latin fractus, meaning broken or fractured. Many natural structures are fractal. Clouds, mountains, the circulatory system or snowflakes are natural fractals.

The most representative food that Mother Nature offers is romanesco broccoli, a cross between broccoli and cauliflower, which has an hypnotic and recurring design. On other occasions fractal foods are forced by the creative hand of man, for example in the dish which interests us here, ‘Fractal Venison’.

What is perhaps more daring is to call a dish by the name of the tool that performs its point-to-point visual implementation, the thermocut. First and foremost, it should be noted that this is a machine that cuts very accurately. The research team was visiting an engineering college and discovered this apparatus, which fascinated us. There it was used to cut material to build models. To us, it seemed perfect for making a few special cuts in fruits and vegetables. The filament is so fine, it allows us to make very amusing cuts (letters or drawings). We can cut fruits, vegetables and jellies just as we want them and then knock them out on the grill or in the oven, dry them or caramelise them.