Salary.

It must be discussed, before you finally agree to take the job. Once they’ve offered it to you.

I hope you know that. I remember talking to a breathless high school graduate, who was elated at having just landed her first job. “How much are they going to pay you?” I asked. She looked startled. “I don’t know,” she said, “I never asked. I just assume they will pay me a fair wage.” Boy! Did she get a rude awakening when she received her first paycheck. It was so miserably low, she couldn’t believe her eyes. And thus did she learn, painfully, what you must learn too: Before accepting a job offer, always ask about salary.

Indeed, ask and then negotiate.

It’s the “negotiate” that throws fear into our hearts. So many of us feel ill prepared to do that.

Well, set your mind at ease; it’s not all that difficult.

While whole books can be—and have been—written on this subject, there are basically just six secrets to keep in mind.

“The end of the interviewing process” is difficult to define. It’s the point at which the employer says, or thinks, “We’ve got to get this person!” That may be at the end of the first (and therefore the last) interview; or it may be at the end of a whole series of interviews, often with different people within the same company or organization, or with a whole bunch of them all at once.

But assuming things are going favorably for you, whether after the first, or second, or third, or fourth interview, if you like them and they increasingly like you, a job offer will be made. Then, and only then, is it time to deal with the question that is inevitably on any employer’s mind: how much is this person going to cost me? And the question that is on your mind: how much does this job pay?

If the employer raises the salary question earlier, say near the beginning of the interview, asking (innocently), “What kind of salary are you looking for?” you should have three responses ready—at your fingertips.

Response #1: If the employer seems like a kindly man or woman, your best and most tactful reply might be: “Until you’ve decided you definitely want me, and I’ve decided I definitely could help you with your tasks or projects here, I feel any discussion of salary is premature.”

That will work, in most cases. There are instances, however, where that doesn’t work. Then you need:

Response #2: You may be face-to-face with an employer who demands within the first two minutes of the interview to know what salary you are looking for. That is not good, especially since 2008, as some employers can afford to be really picky, since—in their minds—there is a plentiful bunch of job-hunters to choose from. So, here, you may need a backup response, such as: “I’ll gladly answer that, but could you first help me understand what this job involves?”

That is a good response, in most cases. But what if it doesn’t work? Then you’ll need to fall back on:

Response #3: The employer with rising voice says, “Come, come, don’t play games with me. I want to know what salary you’re looking for.” Okay, that’s that. You have to come clean. But you don’t have to mention a single figure; instead you can answer in terms of a range. For example, “I’m looking for a salary in the range of $35,000 to $45,000 a year.”

If that still doesn’t satisfy them, then clearly you are being interviewed by an employer who has no range in mind. Their beginning figure is their ending figure. No negotiation is possible.1 This happens, when it does, because many employers since 2008 are making salary their major if not sole criterion for deciding who to hire, and who not to hire. It’s an old game: among two equally qualified candidates, the one who is willing to work for the least pay, wins. And that is that!

If you run into this situation, you may decide this isn’t the kind of place you want to work at, for if they’re inflexible in this, what else will they be inflexible about, once you take the job? You’ve been warned. Microcosm equals macrocosm.

On the other hand, if you’re flat broke and you need this job—any job—desperately, you will have no choice but to give in. Ask what salary they have in mind, and make your decision. (Of course you can always try postponing your decision a day or so, by saying, “I need a little time, to think about this.”)

However, all the foregoing is merely the worst-case scenario. Usually, things won’t go this badly, where you feel so powerless.

In most interviews these days, the employer, alone or in a group, will be willing to save salary negotiation until they’ve finally decided they want you (and you’ve decided you want them). And at that point, the salary will be negotiable. I’ll explain why in the next Secret.

For now, let me hammer home this first Secret: it is in your best interest to not discuss salary until all of the following conditions have been fulfilled:

• Not until they’ve gotten to know you, at your best, so they can see how you stand out above the other applicants, and therefore how you’re worth more than they would pay them.

• Not until you’ve gotten to know them, as completely as you can, so you can tell if this really is a place where you want to work.

• Not until you’ve found out exactly what the job entails.

• Not until they’ve had a chance to find out how well you match their job requirements.

• Not until you’re in the final interview at that place, for that job.

• Not until you’ve decided, “I really would like to work here.”

• Not until they’ve conveyed to you their feelings, such as: “Well that’s good, because we want you.” Or, better yet:

• Not until they’ve conveyed the feeling, “We’ve got to have you.”

If you’d prefer this be put in the form of a diagram, here it is:

To download a printable PDF of this image, please visit http://rhlink.com/wciyp2015005

It all boils down to this: if you really shine during the hiring-interview, they may—at the end—offer you a higher salary than they originally had in mind when the interview started. And this is particularly the case when the interview has gone so well, that they’re now determined to obtain you.

Negotiation. There’s the word that strikes terror into the hearts of most job-hunters or career-changers. Why do we have to negotiate?

Simple. It would never be necessary if every employer in every hiring-interview were to mention, right from the start, the top figure they are willing to pay for that position. A few employers do. And that’s the end of any salary negotiation. But most employers don’t.

They know, from the beginning of the interview, the top figure they’re willing to pay for this position under discussion. But. But. They’re hoping they’ll be able to get you for less. So they start the bidding (for that is what it is) lower than they’re ultimately willing to go.

And this creates a range.

A range between the lowest they’re hoping to pay, vs. the highest they can afford to pay. And that range is what the negotiation is all about.

For example, if the employer can afford to pay you $30 an hour, but wants to try to get you for $18 an hour, the range is $18–$30.

You have every right to try to negotiate the highest salary that employer is willing to pay you, within that range.

Nothing’s wrong with the goals of either of you. The employer’s goal is to save money, if possible. Your goal is to bring home to your own household the most money that you can, for the work you will be doing.

Where salary negotiation has been successfully kept offstage for much of the interview process, when it finally does come up, you want the employer to be the first one to mention a figure, if you possibly can.

Why? Nobody knows. But it has been observed over the years that where the goals are opposite, as in this case—you are trying to get the employer to pay the most they can, and the employer is trying to pay the least they can—whoever mentions a salary figure first, generally loses. You can speculate from now until the cows come home, as to why this is so. There are a dozen theories. All we really know for sure is that it is true.

Inexperienced employer/interviewers often don’t know this strange rule. But experienced ones are very aware of it. That’s why they will try to get you to mention a figure first, by asking you some innocent-sounding question, like: “What kind of salary are you looking for?”

Well, how kind of them to ask me what I want—you may be thinking. No, no, no. Kindness has nothing to do with it. They are hoping you will be the first to mention a figure, because they’ve learned this lesson from ten thousand interviews in the past.

Accordingly, if they ask you to be the first to name a figure, the simple countermove you should have at the ready, is: “Well, you created this position, so you must have some figure in mind, and I’d be interested in first hearing what that figure is.”

As I said, salary negotiation is required anytime the employer does not open the discussion of salary by naming the top figure they have in mind, but starts instead with a lower figure.

Okay, so here is the $64,000 question: how do you tell whether the figure the employer first offers you is only their starting bid, or is their final final offer? The answer is: by doing some research on the field and that organization, before you ever go in for an interview.

Oh, come on! I can hear you say. Isn’t this more trouble than it’s worth? No, it’s not. If you want to win the salary negotiation. There is a financial penalty exacted from those who are too lazy, or in too much of a hurry, to go gather this information. In plain language: if you don’t do this research, it’ll cost ya!

Let’s say it takes you from one to three days to run down this sort of information on the three or four organizations that interest you the most. And let us say that because you’ve done this research, when you finally come to the end of the final interview for a job there, you are able to ask for and obtain a salary that is—oh, let’s say—$15,000 a year higher than you would otherwise have gotten. (That’s not unrealistic.)

In the next three years, then, you will be earning $45,000 extra because of your salary research. Not bad pay, for just one to three days’ work! And it can be even more.

It doesn’t always happen; but I know many job-hunters and career-changers to whom it has. It’s certainly worth a shot.

Okay, then, how do you do this research? Well, there are two ways to go: online, and off. Let’s look at each, in turn.

If you have access to the Internet—at home or at your library or at an Internet café2—and you want to research salaries for particular geographical regions, positions, occupations, or industries, or even (sometimes) organizations, here are some free sites that may give you just what you’re looking for:

• http://jobstar.org/tools/salary/index.cfm: This site is a treasure trove. It links to 300 different sites that maintain salary lists, and joy, joy, it is kept updated. It’s one of the largest and most complete lists of salary reviews on the Web, maintained by a genius named Mary Ellen Mort. This is a treasure.

• www.salary.com: The most visited of all the salary-specific job-sites, with a wide variety of information about salaries. It was started by Kent Plunkett, and acquired by Kenexa Corporation in August 2010. It has expanded a lot, over the years. Roll over the green navigation bar at the top to see all its resources.

• www.bls.gov/ooh: The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ survey of salaries in individual occupations, from the Occupational Outlook Handbook 2012–2013. It lists jobs that are highest paying, and/or jobs that are the fastest growing, and/or jobs that have the highest number of openings.

• http://stats.bls.gov/oes/oes_emp.htm: The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ survey of salaries in individual industries (it’s a companion piece to the Occupational Outlook Handbook). Over a period of three years, it surveys 1.2 million establishments to get their figures.

• www.MyPlan.com: This site has a list of the highest-paying jobs in America for those without a college degree (under Careers, click on Top Ten Lists).

• www.salaryexpert.com: When you need a salary expert, it makes sense to go to “the Salary Expert.” Lots of stuff on the subject of salaries here, including a free “Salary Report” for hundreds of job-titles, varying by area, skill level, and experience. It also has some salary calculators. I find the site a little complicated to navigate, but maybe that’s just me.

If you “strike out” on all the above sites, then you’re going to have to get a little more clever, and work a little harder, and pound the pavement, as I shall describe next.

Okay, so how do you do salary research offline? Well, there’s a simple rule: generally speaking, abandon books, and go talk to people.

Use books and libraries only as a second, or last, resort. You can get much more complete and up-to-date information from people who are doing the kind of job you’re interested in, maybe at another company or organization than the one(s) you’re interested in.

If you don’t know where to find them, talk to people at a nearby university or college who train such people, whatever their department may be. Teachers and professors will usually know what their graduates are making. Also you can go visit actual workplaces.

Let’s look at some concrete examples:

First Example: A fast food place. You may not need to do any salary research. They pay what they pay. You can walk in, ask for a job application, and interview with the hiring manager. He or she will usually tell you the pay, outright. It’s usually set in concrete. But at least it’s easy to discover what the pay is. (Incidentally, filling out an application, or even having an interview there, doesn’t mean you have to take that job—but you probably already know that. Just say, “I need to go home and think about this.” You can decline any offer from any place. That’s what makes this approach harmless.)

Second Example: A construction company. This is typical of a place where you can’t discover what the pay is, right off the bat. If you’re actually going to try to get work at that construction company but you want to research salaries before you go for an interview, the best way to do this research is to go visit a different construction company in the same town or geographical area—one that isn’t of much interest to you—and ask what people make there. Or, if you don’t know who to talk to there, fill out one of their applications, and talk to the hiring person about what kinds of jobs they have (or might have in the future)—at which time prospective wages is a legitimate subject of inquiry. Then, having done this research on a place you don’t care about, go back to the place that really interests you, and apply. You still don’t know exactly what they pay, but you do know what their competitor pays—which will usually be close to what you’re trying to find out.

Third Example: A one-person office (besides the boss, obviously), working say as an administrative assistant. Here you can often find useful salary information by perusing the Help Wanted ads in the local newspaper for a week or two, assuming you still have a local paper! Most of the ads won’t mention a salary figure, but a few may. Among those that do, note what the lowest salary offering is, and what the highest is, and see if the ad reveals any reasons for the difference. It’s interesting how much you can learn about administrative assistants’ salaries, with this approach. I know, because I was an administrative assistant myself, once upon a time.

There’s a lot you can find out by talking to people. But another way to do salary research—if you’re out of work and have time on your hands—is to find a Temporary Work Agency that places different kinds of workers, and let yourself be farmed out to various organizations: the more, the merrier. It’s relatively easy to do salary research when you’re inside a place. (Study what that place pays the agency, not what the agency pays you after they’ve taken their “cut.”) If you’re working temporarily at a place where the other workers really like you, you’ll be able to ask questions about a lot of things there, including salary.

Okay, I admit this is a bit sophisticated, and you may not have the stomach to do this much research. But you ought to at least know how this works. Just in case.

It begins by defining your goal. What you want, in your research, is not just one salary figure. As you may recall, you want a range: a range defined by what’s the least the employer may offer you, and what’s the most the employer may be willing to pay to get you. In any organization that has more than five employees, that range is comparatively easy to figure out. It will be less than what the person who would be above you makes, and more than what the person who would be below you makes. Examples:

One teensy-tiny little problem here: how do you find out the salary of those who would be above and below you? Well, first you have to find out their names or the names of their positions.

If it is a small organization you are going after—one with twenty or fewer employees—finding out this information should be easy. Any employee who works there is likely to know the answer, and you can usually get in touch with one of those employees, or even an ex-employee, through your own personal “bridge-people”—people who know you and also know them. Since up to two-thirds of all new jobs are created by small companies of this size, that’s the kind of organization you are likely to be researching, anyway.

On the other hand, if you are going after a larger organization, then you fall back on a familiar life preserver, namely every person you know (family, friend, relative, business, or spiritual acquaintance) and ask them who they know that might know the company in question, and therefore, the information you seek. LinkedIn should prove immensely helpful to you here, in locating such people. If you’re not already on it, get on it (www.LinkedIn.com/reg/join).

Maybe this will be easy. Maybe it won’t be: it’s possible you’ll run into an absolute blank wall at a particular organization (everyone who works there is pledged to secrecy, and they have shipped all their ex-employees to Siberia). In that case, seek out information on their nearest competitor in the same geographic area. For example, let us say you were trying to find out managerial salaries at Bank X, and that place was proving to be inscrutable about what they pay their managers. You would then turn to Bank Y as your research base, to see if the information is easier to come by, there. And if it is, you can assume the two may be basically similar in their pay scales, and that what you learned about Bank Y is probably applicable to Bank X.

Note: In your salary research take note of the fact that most governmental agencies have civil service positions paralleling those in private industry—and government job descriptions and pay ranges are available to the public. Go to the nearest city, county, regional, state, or federal civil service office, find the job description nearest the kind of job you are seeking in private industry, and then ask the starting salary.

When this is all done, if you want to be a true expert at this game then you’re going to have to do a little bit of math, here.

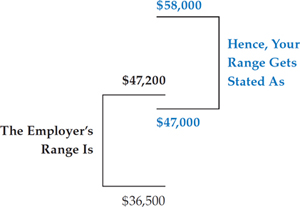

Suppose you guess that the employer’s range for the kind of job you’re seeking is $36,500 to $47,200. Before you go in for the interview, anywhere, you figure out an “asking” range for yourself, that you’re going to use when and if the interview gets to the salary negotiation part. This asking range is clever, in that it should “hook in” just below that employer’s maximum, and then go up from there. This diagram shows you how this works:

And so, when the employer has stated a figure (probably around their lowest—i.e., $36,500), you will be ready to respond with something along these lines: “I understand, of course, the constraints under which all organizations are operating these days, but I am confident that my productivity is going to be such, that it will justify a salary”—and here you mention the range above, where your bottom figure starts just below the top of their range, and goes up from there—“in the range of $47,000 to $58,000.”

It will help a lot during this discussion, if you are prepared to show in what ways you will make money or in what ways you will save money for that organization, such as would justify precisely this higher salary you are asking for. Even if they accept your offer at the bottom of your range, you are still near the top figure they’re willing to pay.

Yes, it’s clever. Yes, it’s risky. Yes, it takes some work. But you’re got the brains to pull it off. You’ve got the brains to be good at this salary negotiation game.

What if, after all the trouble you went to, this just doesn’t work? At least, at that place. The employer has a ceiling they have to work with, it’s below what you’re asking, and you are unwilling to lower your definition of what you’re worth?

Daniel Porot, job-expert from Switzerland, suggests that if you’re dying to work there, but they cannot afford the salary you need and deserve, you might consider offering them part of your time.

If you need, and believe you deserve, say $50,000 annually, but they can only afford $30,000, you might consider offering them three days a week of your time for that $30,000 (30/50 = 3/5 of a five-day workweek). This leaves you free to take work elsewhere during those other two days. You will of course determine to produce so much work during those three days per week you are there, that they will be ecstatic about this bargain—won’t you?

Salary negotiation with this employer is not finished until you’ve addressed more than salary. Unless you’re an independent contractor, you want to talk about so-called fringe benefits. “Fringes” such as life insurance, health benefits or health plans, vacation or holiday time, and retirement programs typically add anywhere from 15%–28% to many workers’ salaries. That is to say, if an employee receives $3,000 salary per week, the fringe benefits are worth another $450 to $840 per week.

So, before you walk into an interview you should decide what benefits are particularly important to you. And then, after the basic salary discussion is settled, you can go on to ask them what benefits they offer there. If you’ve given this any thought beforehand, you should have already decided what benefits are most important to you, and be ready to fight for those.

And when all this is done, the discussion of the job, the finding out if they like you and if you like them, the salary negotiation, and the concluding discussion of benefits, then you want to get everything they’re offering summarized, in writing. Believe me you do. In writing, or typing, and signed.

Many executives unfortunately “forget” what they told you during the hiring-interview, or even deny they ever said such a thing. It shouldn’t happen; but it does. Sometimes they honestly forget what they said.

Other times of course, they’re playing a game. Or their successor is, who may disown any unwritten promises you claim they made to you at the time of hiring. They may respond with, “I don’t know what caused them to say that to you, but they clearly exceeded their authority, and of course we can’t be held to that.”

I repeat: get it all in writing. And signed. It’s called a letter of agreement—or employment contract. If it is a small employer (10 or fewer employees) they may not know how to draw one up. Just put the search term “sample letter of agreement between employer and employee” into your favorite search engine, and you’ll get lots of free examples. I particularly like the one from Inc.com. You or the employer can write this up. Then they can sign it.

You have every right to ask for this. If they simply won’t give it to you, beware.

Remember, job-hunting always involves luck, to some degree. But with a little bit of luck, and a lot of hard work, and determination on your part, these instructions thus far in this book, should work for you, as they have worked for so many hundreds of thousands before you.3

But. Maybe it won’t. Maybe you’ll faithfully follow everything in these first five chapters, and you still can’t find a job. Tempting, at that point, to think it’s just the sluggish economy, isn’t it? The only irritating little fact: there were eight million vacancies last month. Why didn’t you get one of them?

There must be something different that you can do. Right?

There sure is.

That’s what the rest of this book is about.

1. One job-hunter said his interviews always began with the salary question, and no matter what he answered, that ended the interview. Turned out, this job-hunter was doing all the interviewing over the phone. That was the problem. Once he went face to face, salary was no longer the first thing discussed in the interview.

2. For a directory of Internet cafes around the world, see www.cybercafes.com.

3. Here is a letter from a job-hunter who had great success:

Before I read this book, I was depressed and lost in the futile job-hunt using Want Ads only. I did not receive even one phone call from any ad I answered, over a total of four months. I felt that I was the most useless person on earth. I am female, with a two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, a former professor in China, with no working experience at all in the U.S. We came here seven months ago because my husband had a job offer here.

Then, on June 11th of last year, I saw your book in a local bookstore. Subsequently, I spent three weeks, ten hours a day except Sunday, reading every single word of your book and doing all of the flower petals in the Flower Exercise. After getting to know myself much better, I felt I was ready to try the job-hunt again. I used Parachute throughout as my guide, from the very beginning to the very end, namely, salary negotiation.

In just two weeks I secured (you guessed it) two job offers, one of which I am taking, as it is an excellent job, with very good pay. It is (you guessed it again) a small company, with twenty or so employees. It is also a career-change: I was a professor of English; now I am to be a controller!

I am so glad I believed your advice: there are jobs out there, and there are two types of employers out there, and truly there are! I hope you will be happy to hear my story.