If your job-hunt isn’t going well, the idea may occur to you in some moment of desperation: maybe I should stop trying to find jobs where I work for someone else. Maybe I should start my own business.

Some people have always wished they didn’t have to work for someone else, but could be their own boss. According to some surveys, up to 80% of all workers toy with this idea at some point in their lives.1 People dream. Maybe your dream is: I want to create a website where I can teach people how to “go green,” and help preserve the environment. Or maybe your dream is: I want to sell jewelry. Or maybe: I want to start my own security service. Or maybe it is: I want to run my own bake shop, where I can sell my own homemade bread and pies. Or: run a bed-and-breakfast place. Or: grow lavender, and sell soap and perfume made from it. Or: be a consultant to people who need my expertise, gathered in the business world over many years. Or: I want to sell real estate. Stuff like that.

Or maybe you don’t have a dream. All you know is you don’t want to work for someone else; you want to be your own boss. And you’re open to any and all suggestions.

Sometimes taking this step is easy. Sometimes it is super difficult. Let’s consider a couple of real case histories.

Case History #1. A. J. was trained as a physical therapist. He had no difficulty finding work, at local hospitals. But he fretted about always being indoors; he wanted out. He considered his assets: he was a skilled photographer, he was a good furniture finisher, and he loved thrift shops and flea markets. So, to start, he taught himself to become an expert on a certain period of furniture, and learned how much fans of that furniture would pay for pieces from that period. He then began to tour local thrift shops, flea markets, estate sales, and his local craigslist in his area, weekly, and looked for pieces that were for sale at prices below their true worth. He bought the pieces, took them home to his garage, finished them off so they looked beautiful, took attractive well-lighted photos of them, and posted the photos, with prices, on his local craigslist (www.craigslist.org/about/sites). He quickly became known for his expertise, and thereafter people flocked to buy any furniture he displayed on the Internet. In fact, he kept a local list of repeat buyers and would often e-mail them a photo of his latest finds, before listing the item publicly. Naturally, he crafted a mark-up in price from what he had originally paid; and soon he was making—and is still making—a very good living for himself and his family. He is outdoors all the time.

Case History #2. C. W. was a homemaker, with a daughter in her teens. The daughter belonged to an organization that sponsored an annual collection in her small town of stuff that people no longer wanted. C. W.’s daughter was one of those who did the pickup. On an appointed Saturday, that organization then had a town-wide sale, of all the items they had picked up. They made a considerable amount of money. What they couldn’t sell, they took home, confident they would figure out, in the future, what to do with it. The daughter brought home about 150 books. They stored them temporarily, in a room just off the living room. Visitors to that home would see the books, and say, “Oh, this one looks interesting. What are you going to do with it?” You can buy it, was the answer. Pretty soon, C. W. was doing a thriving business in her home, as visitors picked over the books she had, bought them, and often dropped off their own books that they no longer wanted. Soon, the house was inadequate for the task, so C. W. rented a storefront downtown, and titled it C. W.’s Used Books. She created a website to advertise the kinds of books she had, her business hours, etc. It became a thriving business.

Case History #3. R. J. was a returning veteran. She began by getting a job doing programming for a large employer, then slowly decided she wanted to go out on her own. She chose a field that she knew quite a bit about, and started a website in that field. She used Google ads and other vendors to monetize the site, and soon was making a decent living as her website became the “go-to” place for people who wanted the kind of information she had to offer.

These are real-life stories; I only changed the names to protect their privacy.

You will notice, right away, some things that are common to these case histories:

a) These people didn’t need a whole lot of money to launch their own business.

b) They did have to do research, sometimes plenty of it, to make it work.

c) All three of them used the Internet to make their product, service, or expertise, known.

d) None of them went down the traditional paths that people used to go down, when considering self-employment: such as buying a franchise, or being sucked in by one of those well-advertised “work-at-home” projects that used to sound appetizing to the unwary. “Being self-employed” wears quite a different face these days, compared to what it used to.

So, now you’re reading this chapter, and you’re weighing the idea of going out on your own, starting your own business, being your own boss. Where do you start?

In this first scenario, we assume you want to be your own boss, but you have no idea what kind of business you want to have. How do you start? There are four steps, that any thorough, intelligent person should faithfully follow: Write. Read. Explore. Get Feedback.

1. Begin with chapter 7 in this book: You Need to Understand More Fully Who You Are. Don’t just read it. Do it! As I repeat throughout this book, Who precedes What. First get a clearer picture of Who you are, before you try to decide What you want to do. Ultimately, what you decide to do should flow from who you are. When done, look at your whole Flower Diagram and see if any of the petals gives you an idea for your own business.

2. Get out a piece of blank paper, and jot down any ideas. Use this same piece of paper for any ideas that come to you, as you do the rest of these steps. You want it all on one page. (Something to do with the right side of your brain, and intuition.)

3. Then write your resume, if you haven’t already, answering all the questions you will find in chapter 2, under the heading: A Starter Kit for Writing Your Resume. When done, read it all over, and see if anything there gives you an idea for a business of your own. It may be that you have been doing it for years—but in the employ of someone else. But now, you’re thinking about doing this kind of work for yourself, whether it be as an independent accountant, massage therapist, business consultant, repair person, dance instructor, home decorator, home care nurse, craftsperson, or producer or seller of some kind of product or service. If so, add your great idea on that piece of paper.

4. If nothing inspires you, try Daniel Pink’s prescription:2

a. Make a list of 5 things you are good at.

b. Then make a second list of 5 things you love to do.

c. Then make a third list of where the first two lists overlap.

d. Read that list. Ask yourself, “Will anyone pay me to do these things?”

5. If you’re dying to be your own boss, but still have no idea what business to go into, try this: go to O*NET (www.onetonline.org). Click on Occupations, then, underneath it, click on Career Clusters. Look at that list and see if any cluster appeals to you. Jot it down on that piece of paper. Then go back to the home page and under Advanced Search, click on Browse by O*NET Data. You will see there are nine subheadings beneath that title: Abilities, Interests, Knowledge, Skills, Work Activities, Work Context, Work Values, Skills Search, and Tools and Technology. Click on each of those nine, in turn, and jot down anything that proves to be attractive or interesting, again, on that piece of paper.

Hopefully, from all this thinking, and tasks, you will have some ideas. It will be nice if you see the possibilities of three different business ventures. But if there’s one of the three that you would really die to do, and you feel passionate about it, then explore that one first. Second. And third!

Now, what you want to do next is read up on all the virtues and perils of running your own business. Look before you leap! The Internet has tons of stuff about this. For example:

Free Agent Nation

www.workforce.com/articles/dan-pink-interview-free-agent-nation-evolves

Daniel Pink, before he became famous for such books as Drive and A Whole New Mind, was the first to call attention to how many people were refusing to work for any employer. He defined them as free agents. His classic book was Free Agent Nation. His basic thesis: self-employment has become a broader concept than it was in another age. The concept now includes not only those who own their own business but also free agents: independent contractors who work for several clients; temps and contract employees who work each day through temporary agencies; limited-timeframe workers who work only for a set time, as on a project, then move on to another company; consultants; and so on. This is a fascinating article to help you decide if you want to be a “free agent.”

Working Solo

www.workingsolo.com/resources/resources.html

This site gives you a whole bunch of resources if you decide to start your own business.

Small Business Administration

www.sba.gov

The SBA has endured some bad press in the past five years, but keep in mind that it was established to help start, manage, and grow small businesses. Lots of useful articles and advice are online, here, including such subjects as “Make Your Small Business Easily Found Online.” Click on “Starting and Managing” at the top.

A Small Business Expert

http://asmallbusinessexpert.com

Scott Steinberg, a hugely popular analyst and industry insider for all the major TV networks, has produced a Business Experts Guidebook, for those considering starting their own business. It’s $12.59, but he will let you download it to your Kindle or iPad or whatever, for free! Unbelievably comprehensive! Scroll further down the home page of his website and you will see that he also allows you to download a free 2012 Online Marketing Guide.

Business Owner’s Toolkit

www.toolkit.com/small_business_guide/index.aspx

Yikes, there is a lot of information here for the small business owner. Everything about your business: starting, planning, financing, marketing, hiring, managing, getting government contracts, taxes—all that stuff, including any forms you will need to fill out.

The Business Owners’ Idea Café

www.businessownersideacafe.com/starting_business/index.php

Great, fun site for the small business owner. Lots of practical advice.

Nolo’s Business, LLCs & Corporations

www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/business-llcs-corporations

Lots of practical nitty-gritty stuff here: laws, forms, contracts, and resources needed if you start your own business.

Home Businesses3

www.ahbbo.com/archives.html

To help you make your own home business succeed, this is a great site, with lots of information for you. There are hundreds of articles here.

Let’s hope that now you have some idea for starting your own business. But you know that a lot of start-ups, online and off, don’t make it. You want to avoid this happening to you. You want to interview others who have started the same kind of business, so you don’t make the same mistakes they did. Your exploring, then, should have three steps to it, summarized by this simple formula:

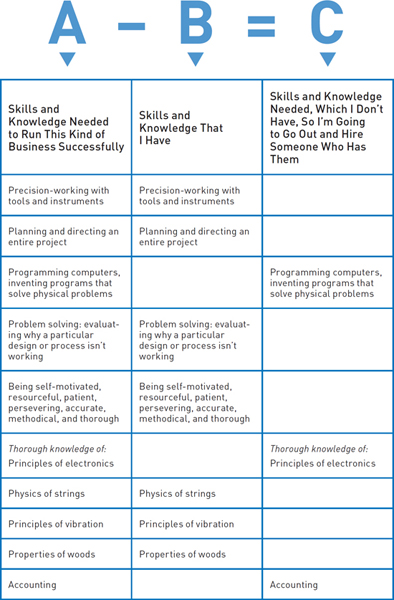

To explain:

You must find out what skills, knowledge, or experience it takes to make this kind of business idea work, by interviewing several business owners. This is List “A.”

Then you need to make a list of the skills, knowledge, or experience that you have. This is List “B.” Then by subtracting “B” from “A,” you will arrive at a list of skills, etc., that are required for success in such a business, that you don’t have. And you must then go out and hire or co-opt a friend or mate or volunteer who has those skills you are lacking (at the moment, anyway). This is List “C.”

I will explain these three steps in a little more detail:

You prepare for these lists by first writing out in as much detail as you can just exactly what kind of business you are thinking about starting. Do you want to be a freelance writer, or a craftsperson, or a consultant, independent screenwriter, copywriter, digital artist, songwriter, photographer, illustrator, interior designer, videographer, film person, filmmaker, counselor, therapist, plumber, electrician, agent, soap maker, bicycle repairer, public speaker, or what?

Then you interview people already doing the kind of work you’d like to do. You should approach this exploration, having found at least three names. Find them through your favorite Internet search engine, or from LinkedIn, Yelp, the Yellow Pages, the Chambers of Commerce, or various Smartphone apps. When you talk to them, you explain that you’re exploring the possibility of starting your own business, similar to theirs, and would they mind sharing something of their own history. You ask them what skills, knowledge, or experience they think are necessary to making this kind of business successful.

These days, everyone’s preference is to do such interviewing by e-mail. I think this is a big mistake. Face to face is to be preferred, in every case. Try businesspeople in a city that’s an hour’s drive away. They are not as likely to see you as a potential competitor, unless you’re both going to compete with each other head to head on the Internet. You want them first of all to tell you something of the history of their business, how they got started, what kinds of challenges they encountered, what kinds of mistakes. Face to face they may tell you more about the challenges they ran into, the obstacles and pitfalls they encountered, than they ever would in an e-mail; and you want this information, believe me you do, so that you can avoid making the same missteps if you decide to start a similar business. (No need for you to step on the same landmines that they did.)

You also want them to help you compile a list of the necessary skills, knowledge, and experience they think are essential for the type of business they’re doing, and you’re thinking of doing.

When you have a list you’re satisfied with, give this list a name. Call it “A.”

Back home you sit down and inventory your own skills, knowledge, and experience, by doing the inventory of who you are described in chapter 7, the Flower Exercise. Give this list a name, also. Call it “B.”

Having done this, subtract “B” from “A.” This gives you another new list, which you should name “C.” “C” is by definition a list of the skills or knowledge that you don’t have, but must find—either by taking courses yourself, or by hiring someone with those skills, or by getting a friend or family member (who has those skills) to volunteer to help you for a while.

For example, if your investigation revealed that it takes good accounting practices in order to turn a profit, and you don’t know a thing about accounting, you now know enough to go out and hire a part-time accountant immediately—or, if you absolutely have no money, maybe you can talk an accountant friend of yours into giving you some volunteer time, for a while.

I can illustrate this whole process with a case history. Our job-hunter is a woman who has been making harps for some employer, but now is thinking about going into business for herself, not only making harps at home, but also designing harps, with the aid of a computer. After interviewing several home-based harp makers and harp designers, and finishing her own self-assessment, her chart of A – B = C came out looking like the example on the next page.

If she decides she does indeed want to try her hand at becoming an independent harp maker and harp designer, she now knows what she needs but lacks: computer programming, knowledge of the principles of electronics, and accounting. In other words, List C. These she must either go to school to acquire for herself, OR enlist from some friends of hers in those fields, on a volunteer basis, OR go out and hire, part-time. It should be always possible—with a little blood, sweat, and imagination—to find out what A – B = C is, for any business you’re dreaming of doing.

To download a printable PDF of this image, please visit http://rhlink.com/wciyp2015022

So, are you cut out for this sort of thing? Only you can answer that, in your innermost thoughts. But you can get some help.

There is a self-examination type questionnaire that you can fill out, at Working Solo (www.workingsolo.com/faqstarting.html#Ans1). It encourages you to ask yourself the hard questions.

There is also a website called Checkster (www.checkster.com.) Scroll down to the bottom of its home page, left-hand side. There you will see “My Checkster. Free Talent Checkup.” Click on it. Set up your free account. Then follow the instructions. You can give Checkster the names and e-mails of six to twelve of your colleagues, friends, or family, who know you well. Checkster will send them, in your name, a request that they answer a few brief questions about you and your past work. Once these are answered, Checkster removes the names, mashes all the responses together, and sends you a summary report, as to your strengths and weaknesses—as perceived by those around you. The report is mailed only to you. The report is free. It should help you make a better decision about whether or not you’re cut out for being your own boss.

Final feedback: It shouldn’t really be necessary for me to say this, but I’ve learned over the years that it is: for heaven’s sake, if you have a spouse or partner, tell them what you’re up to, find out what their opinion is, explore whether this is going to require sacrifices from them (not just you), and how they feel about that. If your life is shared with them, and vice versa, you have no right to make this decision unilaterally, all by yourself. They should be part of the whole journey, not just at the end when your mind is already made up. You have a responsibility to make them full partners in any decision you’re facing. Love demands it!

If after all this feedback, you decide you still want to create your own job by starting this kind of business, go ahead and try—no matter what your well-meaning but cautious friends or family may say. They love you, they’re concerned for you, and you should thank them for that; but come on, you only have one life here on this Earth, and that life is yours (under God) to say how it will be spent, or not spent. Parents, well-meaning friends, etc., can give loving advice, but in the end they get no vote. Just you, your partner … and God.

Just remember, it takes a lot of guts to try ANYTHING new (to you) in today’s brutal economy. It’s easier, however, if you keep these things in mind:

1. There is always some risk, in trying something new. Your goal, I hope, is not to avoid risk—there is no way to do that—but to make sure ahead of time that the risks are manageable.

2. As we have seen, you find this out before you start, by first talking to others who have already done what you are thinking of doing; then you evaluate whether or not you still want to go ahead and try it.

3. Have a plan B, laid out, before you start, as to what you will do if it doesn’t work out; i.e., know where you are going to go, next. Don’t wait, puh-leaze! Write it out, now: This is what I’m going to do, if this doesn’t work out.

1. And each year, 10% of all workers actually do start their own business.

2. Free Agent Nation (Warner, 2001), www.danpink.com/books/free-agent-nation.

3. A lot of people like the idea of a home business, so vultures have taken advantage of that. You will run into ads on TV and on the Web and in your e-mail, offering you a home business “buy-in.” They sound enticing. But, as AARP’s Bulletin back in March 23, 2009, pointed out: of the more than three million Web entries that surfaced from a Google search on the terms “work at home,” more than 95% of the results were scams, links to scams, or other dead ends. Even the sites that claim to be scam-free often feature ads that link to scams. The statistic is: a 48-to-1 scam ratio among ads offering you a nice home business. That’s forty-eight scams for every one true ad. This swamp is filled with alligators!

4. I am indebted to my friend Patrick Schwerdtfeger, author of Marketing Shortcuts for the Self-Employed (Wiley, 2011), for this case history.