Now, then. Have you come to terms with the knowledge that your new home is in a society so unclean that the very water flowing from the earth causes an appalling yearly body count? If you have, you’d probably like some tips on how to keep clean!

Oh, you won’t keep clean.

At least not by twenty-first-century standards. Gracious, no. Even at your best you’ll feel like you’ve just slithered in from two weeks spent camping over a natural sulfur deposit. But you can maintain hygiene acceptable to the standards of the era. And you should. Being dirty kills. There are reams of scientific-ish material on the subject.

Consider the explanation of how filth causes illness, published in 1847’s Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal, volume 10:

“The scurf-skin [dead skin, or dandruff] is being constantly cast off in the form of minute powdery scales; but these, instead of falling away from the skin, are retained against the surface by the contact of clothing. They also become mingled with the unctuous and saline products of the skin, and the whole together concrete into a thin crust, which, by its adhesiveness, attracts particles of dust of all kinds, soot and dust from the atmosphere, and particles of foreign matter from our dress.”

You are a magnet for every airborne poison, disease, and blind gypsy’s curse you encounter. Thus your other organs—lungs, kidneys, liver, and the like—must overextend themselves trying to compensate for how disgusting you are. They will lose. Says Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal,

“The Oppressed organs must suffer from exhaustion and fatigue, and must become the prey to disease. Thus, obviously and plainly, habits of uncleanliness become the cause of consumption and other serious diseases of the vital organs.”

It’s time for a bath, dear. We must save you from your own repugnancy.

Bathing has to be done very particularly. And in this era, doing something right often means doing it as uncomfortably as possible. Otherwise it might appear you’re taking pleasure in unwholesome activities, which are pretty much anything that doesn’t include bracing morning walks and reading the Old Testament. And taking pleasure in your own body, well—you’re obviously not reading the right parts of the Old Testament reverently enough if you think that’s acceptable.

Bathing styles here vary with social class and geography. Most people prefer not to bathe everything at once, unless it’s summer, because the warm air means you’ll be less likely to die from bathing. Wetting the whole body at once strips it of its natural defenses and is sure to result in derangement, raving fevers, and consumption. Until later in the century, when wetting the whole body at once will become the cure for those conditions.

Sponge baths are a popular option, but not the kind of luxurious sponge baths administered by an attractive nurse of your preferred gender. No, you give them to yourself, standing nude in your own freezing bedroom or water closet, usually with cold water and a touch of vinegar or some other additive intended to make the experience less pleasant and more wholesome. Victorians favor sponge baths not just for their cleansing properties, but for the good hard burnishing they involve, invigorating the blood that eeks through your freezing skin. (Do not perform these ablutions in a warm room. It will lead to torpor, masturbation, and, like everything else in the nineteenth century, consumption.)

Bath temperature is a point of serious contention. Even women authors, or at least authors claiming to be women, join the chorus of caution. Mrs. A. Walker, authoress of 1840’s Female Beauty, as Preserved and Improved by Regimen, Cleanliness and Dress, weighs in on the mind-rending terrors of hot bathing:

“Nothing is more likely to awaken many irritations, than baths taken at too high temperature. The effects of a hot bath are evidently debilitating. The body loses too much in such a bath. Baths heated to above 110 degrees have lately, in several instances, been known to produce immediate insanity.”

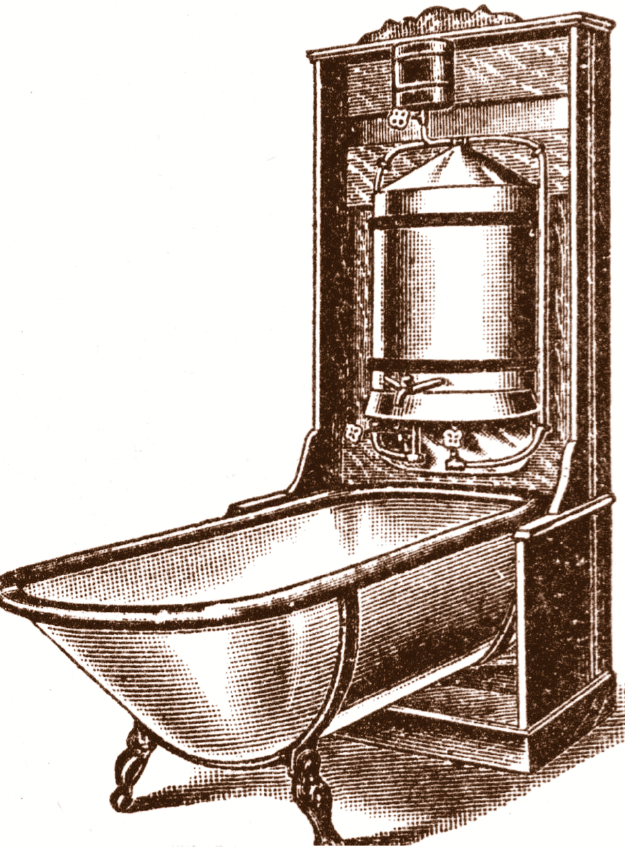

See the little water heater on the wall? That’s where the depravity comes from.

Interestingly, 110 is a popular temperature for modern hot tubs and Jacuzzis. As we now know, such vessels do frequently induce a kind of insanity, causing people to strip themselves of both morals and swimwear and dive headfirst into fleshy madness laden with regret. I daresay Mrs. Walker saw that coming.

Oh, but the cold bath, though it feels painful and pious, can be just as detrimental. Says 1833’s The Toilette of Health, Beauty, and Fashion, written by an anonymous expert (as a great many beauty and hygiene books were during this era) and published in Boston by Allen and Ticknor:

“Considered as a cosmetic, the cold bath possesses no virtue whatever; it renders the skin hard and scaly; and this induration of the skin may prove injurious to health, by checking too suddenly the insensible perspiration.”

Scaly skin, resulting from cold bathing, prevents proper perspiration, promoting poison pores. Precisely. Whereas:

“Warm baths contribute greatly to the preservation of the complexion, by giving freshness and an exquisite color to the skin. Hippocrates recommends the washing of children with warm water, to protect them from convulsions, to facilitate their growth, and to heighten their colour.”

Hippocrates was brilliant. He was also dispensing this health advice over two millennia before the publication of Allen and Ticknor’s book. He claimed that menstruating virgins risked having blood build up in their heart and lungs, causing sluggishness and insanity. Which, actually, hasn’t entirely been disproved by this era…

Moving on. Let’s say you are a lady of wealth in the latter part of the century—a lady in need of washing. You go down the hall and step into that most modern of conveniences, the indoor bathroom. Immediately you are confused. There are so many kinds of baths. Foot baths, hip baths, full immersion baths, shower-baths, and douches. No, not what you think.

In twenty-first-century French, prendre une douche still means what it did in nineteenth-century English: to shower. It had medical overtones then, but not specifically the medicine of the vagina. As described in the 1879 A Treatise on Hygiene and Public Health, volume 1, edited by Albert Henry Buck,

“The douche consists in a stream of water, varying in size and force, applied at a greater or less distance against different parts of the body. The douche exercises a certain amount of friction and a continuous pulse on the spot to which it is applied. It quickens the circulation, and is said to favor the absorption of various diseased deposits. Its effects are so powerful that it cannot be applied for a long time.”

Eventually the necessity of pulse and friction to remove “diseased deposits” lessened, and the douche treatment evolved into something more familiar. The douche streams were mounted on walls and became, in English at least, “showers.” Meanwhile, using a very specific “continuous pulse of water” became a fashionable way for ladies to maintain intimate cleanliness. Ladies clung to the French word, however, to bring dignity and that ever-popular French mystique to the activity. How much more pleasant to murmur “Tsk-tsk, mon amour. Je vais prendre une petite douche” with a whimsical wink when your lover asks where you’re disappearing to than to say “I will now flood my vaginal canal with water in hopes of rinsing away offensive odors and foreign bacteria. Stud.”

Which brings us to another form of bathing, one that will not survive long into the twentieth century—the sitz bath, or hip bath, which is a bit like a porcelain (or tin, depending on your finances) bench in which you can sit, with only your fundamental bits submerged. In an era when filling a tub is an exhausting undertaking and sponging a freezing and filthy business, the simple sitz bath is a revelation. It attends directly to your most troublesome parts with minimum fuss and is a godsend for menstrual and postpartum hygiene.

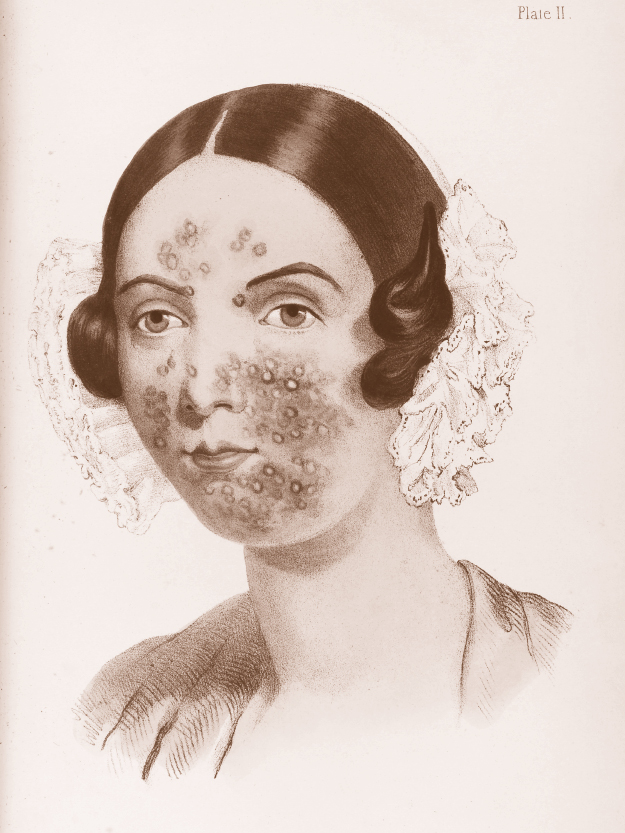

That acne represents some serious disease deposit. You should have face-douched more.

But no one will say that out loud. So instead the sitz bath is recommended for infirm persons, who can be comfortably sponged off without having the deadly pressure of a full bath compressing their sickly chests and giving them consumption. But really the point of the sitz bath is to provide quick, soothing sanitation to the dirtiest division of your personage. You can rinse away whatever the Sears catalog has not wiped and, by adding the right ingredients, provide spot-on treatment for chafing, hemorrhoids (called piles), and the bevy of venereal diseases your husband brings home.

Now, bathe safely.

According to A Treatise on Hygiene and Public Health:

• Certain precautions must always be exercised in bathing of whatever sort.

“Oh, I don’t know, Clara, are you sure this is safe? I just ate some filberts.”

• The bath should not be taken “on an empty stomach”—that is, when one is conscious of being hungry—or when one is fatigued. Nor should it follow a meal too closely; three or four hours should be permitted to elapse.

• The proper time for bathing is in the morning, either before breakfast or about noon.

• A good reaction is a necessity to the advantageous use of the bath; unless the bather feels a “glow” after the bath, “it has done him no good and possibly may have done him harm.”

You’re Going to Stink, But You Can Choose Your Stink

Just a quick reminder, darling. Though you are keeping yourself as clean as you can, deodorant and antiperspirant have not been invented. Not until 1888, anyway, when a potted paste called Mum hits the market, designed to be dipped into and applied with your fingertips. It’s slow to reach the masses, though, so don’t hold your breath. Or rather, do hold your breath.

You (and everyone else at an indoor summer cotillion or in a crowded streetcar) will use perfumes and colognes. And scented face wash and scented talc powders and lavender-flavored breath lozenges and heavily perfumed hair pomade. These will be much heavier scents than you’re used to; Victorians favored strong, alcohol-heavy floral aromas over the sweeter and crisper perfumes we prefer today. Because we want to smell sweet and fresh. They wanted to drown out the horrid stench of their own humanity. Yes, the odors may be noxious, but at least it isn’t your own private flesh smell that’s making the gentleman next to you queasy. How distastefully intimate that would be.

Washing Hair. Or Not. Whatever.

There is no consensus on the proper way to clean your hair. In 1881’s Sylvia’s Book of the Toilet: A Ladies’ Guide to Dress and Beauty, Sylvia (the pseudonym of a person who also wrote books instructing ladies in macramé and profitable church bazaars) suggests you begin your hair-care routine in the same manner the modern fertilizer industry begins creating its product: with a good heavy rock of pure ammonia.

Gentlemen: when you’re about to put the moves on your gal, who will probably let you, judging from the amount of skin she’s showing, don’t forget to “perfume the breath” with lavender lozenges.

“Pour upon [the ammonia] a quart of boiling water; when cool enough to allow of the hand being put into the water without the slightest discomfort, beat that member about in the water until a lather is formed. With this rub the roots of the hair all over the head, and then the hair itself.… Take a basin full of warm water and wash out all the lather. Then a douche or two of cold water, after which the head must be thoroughly rubbed until the skin glows.”

President Buchanan’s Inaugural Ball, 1857. That’s the stench of victory, friends.

Ammonia becomes highly corrosive when reacting to water, which would probably be very effective at stripping hair of grime. Also skin of its superfluous top few layers. As for getting the remaining skin to glow, that won’t be hard, since ammonia destroys cells, including blood cells. Like the sort found in your skin and lungs. Oddly enough, frequently breathing in ammonia gas, though so acrid it is painful to inhale and a definite contributor to lung damage, was not considered a cause of consumption.

Sylvia is one of many beauty experts to laud the effects of onion juice for hair growth. If one finds that smell too unpleasant, because one has forgotten one lives in perpetual stink anyway and suddenly one has standards, she suggests adding ambergris, the slightly sweet, slightly flatulent-smelling intestinal seepage of the sperm whale. Ambergris is a very popular ingredient in cosmetics and perfumes here. It will be illegal to own in twenty-first-century America, because of the sperm whale’s endangered-species status (of which the seeking of ambergris and the aforementioned lamp oil was a leading cause). Also it’s whale’s poop-mucus. Stop playing in whale poop-mucus. Just stop.

And how often should the hair be washed? It all depends on your hair and which expert you consult. Also the environment you live in, the season, and of course the fiber of your moral character. An immoral girl is a greasy girl.

Ride as fast as you may, darling, but you can never ride away from your own hair.

Truthfully, with the exception of the general “not often” rule, the standard for hair washing is, again, whatever works.

Scribner’s The Woman’s Book (1894) recommends a wet washing about once a month. Don’t use soap, which will give you dandruff. Eggs, whipped and smeared about your hair, are a better approach. Do you rinse the egg out? Oh, who knows. It hardly makes a difference at this point. No matter what you do, your hair here will not be the hair you’re used to.

Our friend Mrs. Walker has her own opinions.

“Supple moist oily hair may be washed every eight days with lukewarm water. Light hair, which is seldom oily, and the fineness and softness of which obviates the use of pomades, rarely requires washing.”

If the lice come on extra strong, a little vinegar and lard caked on your scalp should suffocate them out. Also there is a possibility they dislike… parsley? So mix that in? Or it might have been paprika. Anise? Nobody likes anise.

Frankly, you can forget the whole thing as long as you’re diligent about brushing. And one more little secret. Instead of washing your hair, says Mrs. Walker, try this: “A little honey dissolved in a very small quantity of spirit, scented with rosemary, &c. is an excellent substitute.”

It also might attract malaria mosquitoes, so be careful. And when all else fails, go with the nuclear option. Perfume that mop with pungent chemical concoctions until the tears in people’s eyes make their vision too bleary to judge cleanliness.

White Washed

In the war on nineteenth-century personal putrescence, there’s one more battle you must prepare for. You came here for the clothes: the swooping femininity, the elegant lines, the delicate fabrics. But how will you keep these beautiful gowns looking their best?

Now you know why all your shoes are leather boots, made of material that can be easily reblacked or rewhited. And now you see why men of all stations favor dark colors in their wardrobe, to better hide the accumulation of unavoidable dirt. So why is it that, besides the boots, the finest pieces of your wardrobe seem to make no concession to the barrage of contaminants that beset you from all sides? No, your beautiful dresses aren’t dark or plain. They’re vibrant, patterned, plumed, and begging for attention.

Well, “begging for attention” is perhaps a little much. Now might be a good time to notice the difference between real “fine dresses” of the era and those created by artists working in oil paints or Hollywood.

Only trollops and the foolishly wealthy dress showily. But you mustn’t be afraid to add a little color and embellishment to your pretty frocks—dirty roads, air, buildings, and other people be darned.

Victorian women knew that their voluminous dresses were difficult to keep clean. That they remained so was an important testament to their delicacy and careful natures. Your clothes must tell the world that you are spotless, in habit, form, and soul. And that you seldom have need to engage in self-sullying activities, like cleaning, cooking, or reading a newspaper that might leave ink on your pink and perfect fingers.

Especially since you will never, ever wash that dress.

You can’t, really. The fabric is too delicate for the boiling lye, plunging, scrubbing, and wringing of the day. There is too much lace and too many embellishments, and although clothing dyes are the boldest and most adherent they’ve ever been, anything but a light spot-clean will deaden the shade of even the most well-dyed fiber.

Victorians didn’t like to wash their outer clothing. That’s why they wore so much underclothing.

“My heavens! How lovely! A ‘wringer,’ you say? Is it for punishing the servants when they are insolent?”

White linen (for the wealthy) and white cotton (for the poor) were very popular fabrics for undergarments precisely because they showed any bit of spoilage. In fact, some people thought the material itself motivated the body to self-clean, sucking the unhealthy elements right out of you in the form of sweat stains. Those clothes were washed much more often.

An especially confident person might even wear white outer garments, like those favored by Puritans centuries earlier. One of the reasons you see so much white in lace, aprons, cuffs, and collars in old paintings is because, since they were nearly impossible to maintain in that condition, they were a subtle way to signal the wealth, immaculate personal habits, and piety of the subject.

She may be a dirty girl, but her linen is white and clean.

You’ll have a handful of tricks to help you keep your dress clean. You may attach the train of your dress to your wrist with a little loop bracelet. You might have a sort of dust ruffle, called a balayeuse, that lies under your hem, secretly separating it from the ground it drags upon.

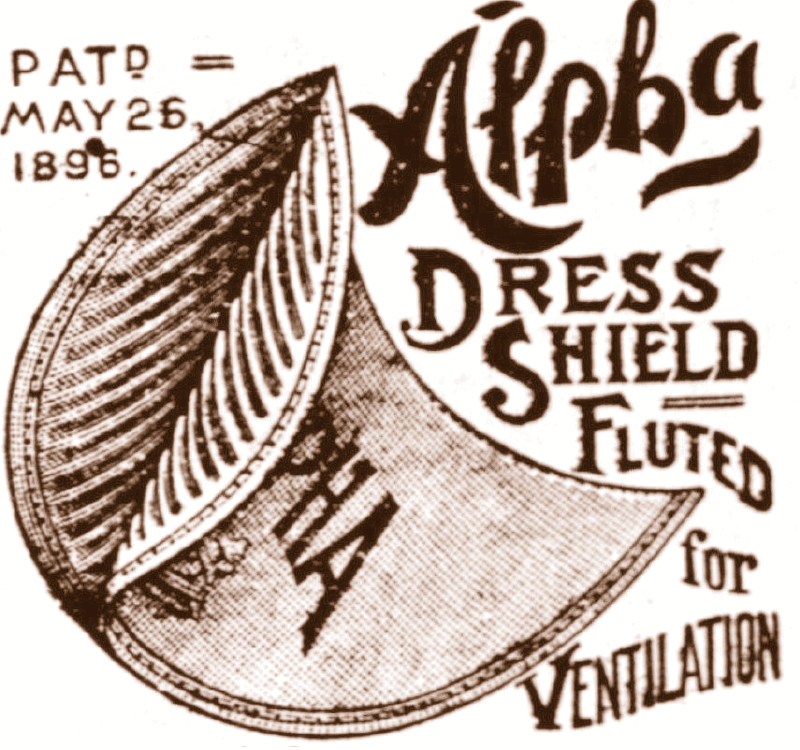

As for keeping your dress free of offensive odors—that just isn’t going to happen, bless your heart. You will air your dress as often as you can. Maybe you’ll get an aerated closet in which to hang your dresses, hoping that the exposure to fresh air will make them less stinky (no urine fumes required in this advanced age). You can also use dress shields, half-moon shapes of absorbent fabric that separate your non-deodorized, hairy armpits from your clothing.

Oh, and yes, you are hairy. Everywhere. There is no such thing as a lady’s razor, although there are many depilatory “creams.” These are chemical suspensions that eat up the keratin protein in your hair. And your face, which is also mostly made of keratin protein. Most of these depilatories, while not explicitly revealing themselves as skin smelters, do recommend only the briefest contact between them and the human body. They are used only on the face, hands, and arms. No other hairy bits will be shown until the 1920s.

All in all, I wouldn’t worry all that much about the state of your hygiene while you’re here. People in this era do not disdain body odor or hair that lacks silky bounce as you’ve been conditioned to. Embrace hygiene as much as you need to feel comfortable, especially when it comes to our next topic: how to menstruate in the nineteenth century.

Alpha dress shields, 1902 Sears, Roebuck catalog