Fancy clothing filled out by a fashionable figure represents but a fraction of your feminine beauty. We have so much more we must do. Being a woman of elegance is a chore, and it has always been so. Consider cosmetics.

Before the nineteenth century, if you wanted to get dolled up special (perhaps in hopes of attracting the eye of the freshly widowed swineherd as he drove his passel of hog flesh past your gate), you would use ingredients from your own garden and your own dead and rendered livestock to do so.

Case in point is the receipt book (British for “recipe book,” past versions of which usually included how-tos for cosmetics and medications as well as food) written by Mrs. Hannah Glasse. In the 1784 edition of her Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy: Which Far Exceeds Any Thing of the Kind Yet Published (probably a reasonable claim, mostly due to the scarcity of printing presses), Glasse offers a recipe for lip rouge made of hog’s lard and beeswax, melted and mixed with the mashed-up root of an innocuous flower called alkanet, all scented with a little lemon. Simple, safe, and hardly whorish at all.

Still, a good woman’s conscience may prick at the thought of unnatural augmentations. For her, there is the advice given in a 1794 edition of The Weekly Entertainer.

INNOCENCE:—A white paint, which will stand for considerable time, if not abused.

MODESTY:—Very best rouge, giving a becoming bloom to the cheek.

TRUTH:—A salve, rendering the lips soft and peculiarly graceful.

MILDNESS:—A tincture, giving sweetness to voice.

TEARS OF PITY:—A water that gives luster and brightness to the eye.

In other words, the best beauty enhancer is to become an ascended saint, the Virgin Mary herself if possible.

I know. Gag me with a wimple. And so hypocritical. Slathering women’s magazines, novels, and advertisements with figures of unattainable beauty is just as common in the nineteenth century as in the twenty-first.

“Makeup? Oh, gracious, no. I look like this because I’ve never heard a swear word.”

Cosmetics were controversial in this era, partly because they were intended to impart the false appearance of youth, which was considered gauche and dishonest. And partly because they were also meant to elevate facial characteristics associated with sexual arousal, such as flushed cheeks, dilated eyes, and reddened lips.

But honestly, I think most of the controversy stemmed from the fact that cosmetics just weren’t very good back then. People could tell when you were painted up, all gaudy and greasy, and it probably looked rather, well, gross. If your foundation is made from lard and poisoned lead, how flattering can it really be? Still, you must make your own decision. Let’s start with a little background information; particularly, the reason most nineteenth-century people have for disdaining a “painted woman.”

Esther: righteously indignant concubine

Jezebel Was Wicked. Wicked Delicious.

Most people don’t consciously connect sin, deceit, and sexuality to cosmetics. But many do subconsciously, even now. This is in part thanks to a biblical character named Jezebel. The word “Jezebel” has a long history of being hissed behind closed doors in reference to women considered too colorful, in both face and reputation. Even today it is still sometimes used as a synonym for a sexually promiscuous or manipulative lady.

Jezebel was an Old Testament queen, the wife of King Ahab, who worshipped the false god Baal. (Ah ah ah… no. We shall not debate which gods are false and which ones are true, Ms. Minored in World Religions. On this journey you are in the Western world as a lady of proper society, and therefore there is One God for you, the Judeo-Christian one. All the other options are Satan deluding the unwashed. If you want to be open-minded and inclusive you should have gone to Berkeley, not the nineteenth century.) Jezebel schemed and murdered her husband’s enemies and did all that stuff people who want to rule empires do. Basically, she was a real saucy piece of work, though there is no evidence she was ever sexually promiscuous. Except that she wore makeup. It’s circular reasoning. Just go with it. She’s not so well remembered for being a brutal tactician who refused to change her religion as she is for this line, describing her as she prepared for the arrival of the godly man she knew was coming to have her killed:

“She painted her face, and tired her head [fixed her hair], and looked out at a window.”

Some think this means Jezebel planned to seduce her way out of this problem; others think she was facing death with composure and dignity.

At any rate, her eunuchs saw that they were on the wrong team and shoved her out the aforementioned window, and dogs ate her face. Which reinforces the assumption that her face was coated in sinfully delicious animal fat.

There are lots of mentions of makeup and adornment in the Bible. Queen Esther, biblical heroine and savior of the Jewish people, was a harem girl, and it took a year of heavy beauty treatments before she was taken on by King Xerxes as one of his favorite concubines. All the while she was lying about her Jewish faith, and when she became queen she asked the king to grant an extra day of bloody massacres and to please impale the corpses of her enemy’s sons on poles. Because that’s what people did in those days. But Jezebel was on the losing side of history, and her act of gussying up as she prepared to face her death cemented her wickedness, and the wickedness of her beauty regime, in the minds of generations.

So between biblical bad girls and millennia of equally bad ingredients, cosmetics had never been considered entirely wholesome. But in the nineteenth century, science—fresh, mad science—had arrived to add some kick to the beauty scene. And the combination of these two temperamental ingredients was downright devilish.

Men of virtue soon began to take notice of the unholy union. Dr. James P. Tuttle wrote in volume 25 of The Medical Record that chemistry was being abused most horrifically by the cosmetics industry for the glory of the morally corrupt.

“The science of chemistry and art of pharmacy have been exhausted to prepare delicate colorings and bright enamels for the complexion. It seems to have been a conception of the ages past that these adornments added to the personal attractions of men as well as women, inflaming passion and calling forth amorous ebullitions in the opposite sex. That it should be held in disrepute will not be questioned, for it was those whose consciences did not falter at whatever means to gain an end—the vicious and vulgar, the harlots and witches—who were the originators of these practices.”

I would not argue with the good doctor, but I would suggest that there have always been women, even a few of spotless character, who want to look young and pretty. Historically, a great deal of a woman’s power lay in her ability to please the eye. The only difference in the nineteenth century was that women could now get their pimple cover-up, hair poofers, wrinkle plumpers, and bosom ballooners from a wildly unregulated chemical industry instead of a farmyard. Even without treacherous eunuchs and dogs waiting to eat your face, vanity was dangerous.

A Droopy Bosom Declares a Droopy Soul

Before we start beautifying your face, we might as well spend our initial energies on the area men are going to look at first. We ought to make sure your bosoms are bouncy, pert, and plump. Or, according to 1890’s Heredity, Health and Personal Beauty, by John Vietch Shoemaker, “the highest [best] type of bosom… is not only placed well up on the chest, but can be best described as of slightly pine-apple form.”

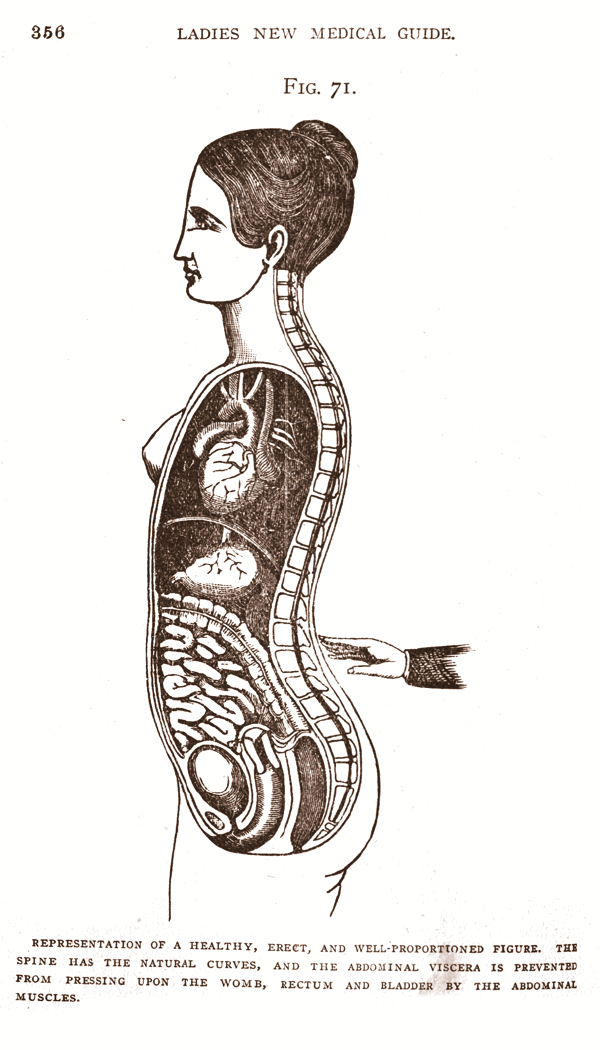

Unhealthy lady with sad bosom

Healthy lady with cheery bosom

Pineapple. Well, fruit can change over the centuries due to advances in agriculture, so maybe a pineapple in 1890 looked entirely different than—huh. Nope. That’s a pineapple, all right.

Pineapple, circa 1890s

Of course most ladies don’t have the good fortune to be born with breasts naturally squat and spiky enough to qualify as top-notch tropical produce. So we look to the experts. As with other “unimportant” facets of female health like beauty and reducing chubstance, it was the lady lecturers of the era who offer the majority of busty advice. Or at least writers claiming to be ladies.

Mrs. S. D. Power does just that in 1874’s The Ugly-Girl Papers, a book intended to help women avoid that distinction. The breasts, she writes, must never be touched but with the utmost delicacy. She cautions never to let a well-meaning nurse or nanny rough up an adolescent bosom in an attempt to inspire its growth. Yes, puzzling and creepy by our standards, but—well—actually it was rather creepy to most of them, too.

She explains:

“It would be unnecessary to say this, were not French and Irish nurses, especially old and experienced ones, sometimes in the habit of stroking the figures of young girls committed to their charge, with the idea of developing them.”

Oh, those Irish. This isn’t the last time we’ll be having trouble with that lot.

No, the proper way to fill out those flat figures, says Mrs. Power, is simple cold water—the discomfort of which will stimulate blood supply—applied morning and night, sponging “always upward, never down” (gently, for we must not aid gravity in its vicious design).

A different approach was advocated by Lola Montez, a brazen (Irish!) dancer and the mistress of Ludwig I of Bavaria, who made her a countess. In her later years she traveled the lecture circuit, advising ladies on how to make themselves worthy of being a king’s bit of boom-boom on the side. She dedicated a whole chapter in her 1858 book, The Arts of Beauty, or Secrets of a Lady’s Toilet, to the care of the beautiful bosom, for, as she quoted from poet Peter Pindar, “Heaven rests on those two heaving hills of snow.”

Montez insists that a girl should not even touch her own developing breasts except when absolutely necessary, and then only with the utmost delicacy. A teenage girl’s buddings should be uncorseted, “as unconfined as a young cedar!” (Are you picturing a skinny little tree with bark-bosoms? I am.) To enhance one’s bustline, she recommends rubbing the following ingredients on them (gently, lest they deflate!), all pretty much just variations on scented water: “tincture of myrrh, pimpernel water, elder-flower water, musk,” and “rectified spirits of wine.” That should get your bodice seams bursting in no time.

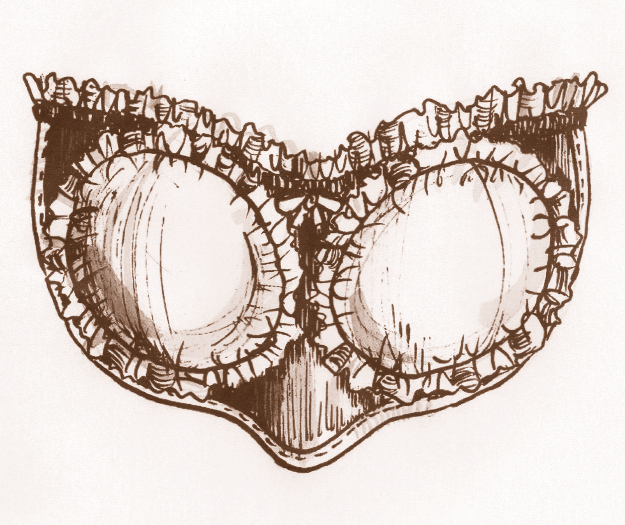

Of course, if it didn’t, you could always “stuff.” Stuffing wasn’t such a desperately childish thing to do back then, as most corset styles flattened what little you had into oblivion. So inserts—basically bust-shaped metal frames made to withstand the pressure—were commonly sold right along with the corsets.

For the lady trying to reduce an overabundant bustline, Countess Montez advises that you not drink iodine, no matter how tempting or fashionable. She suspects it is unhealthy. Rather she recommends rubbing that iodine topically—gently! Your breasts are so delicate they make a baby’s fontanelle look like a granite slab!

Corset insert: sooo much better than wadded-up socks and Kleenex.

Many women turned to the terrifying world of unregulated patent medicine to embiggen their bosoms. In 1869, an unknown author using the pseudonym George Ellington set out to “boldly and truthfully” unveil the disgusting secrets of females in the metropolis, “where sin and immorality have tainted women in high life, and where fashionable wives and beautiful daughters have yielded to the enticer’s arts.” Those arts, he warns his readers in The Women of New York, or The Under-world of the Great City, included something called Mammarial Balm, a stimulating lotion, or “breast food,” that ladies applied to their bosoms and then helped along with suction cups and air pumps until those bosoms swelled. According to Ellington: “A lady makes the application two or three times a week, and in the course of time a breast is developed which suits the taste of the most exacting.”

By modern standards, such methods are nothing short of horrifying.

Mostly because we now know how useless they were. It is not my place to dictate what you choose to do to make your body more husband-entrapping—but if larger breasts really are a concern, tend to it before your journey here. No amount of “breast food” can match the skill of a twenty-first-century surgeon and a bag of silicone. Mr. Fowler, as an example, wouldn’t be fooled by the falsies of the day. That gentleman knows his mammaries.

Nature has not favored you. Shove your palm in Nature’s face and start lathering and pumping.

“False forms compliment natural by imitating them, even representing false nipples as showing through the dress—‘society ladies’ often making love, as General Jackson fought, ‘behind cotton breast works;’ yet they are a shabby substitute, for they never vibrate; whereas natural ones quiver most bewitchingly at every step.”

You might think our Mr. Fowler is verging on the lecherous, but shame on your false modesty. We should consider ourselves lucky to be the recipients of such straight talk from one who obviously has studied the subject so very closely.

And for that matter, thank you, Mr. Fowler, for bringing up the nipple. The nipples, if you did not know, are the semaphore flags of the womb. Says Fowler,

“A girl whose bosom and nipples have just begun to form, catches a hard cold, which strikes to and palsies her womb, and stops its growth, and thereby their’s. All nipple states tell all womb states, the nipples being larger or smaller as womb is either; they standing right out distinctly when it is well organized, and flat and imperfect when it is poor; their surrounding color bright red when it is rigorous and healthy, pale when it is dormant, and brownish, or yellowish, or darkish.”

In other words, if a gentleman requests a nipple inspection before undertaking a marriage contract, you must understand where he is coming from. If you refuse him access to this important information, don’t be surprised if he suspects you of trying to conceal a bilious womb and takes his leave of you.

Corpse’s Curls and Sultry Scalp Grease

On to your crowning glory! As a nineteenth-century lady you have most likely let your hair grow unimpeded from childhood, a trend that will not change until the 1920s. Management of that mane is one more way the world judges your femininity. If you can’t arrange a modest but fetching topknot, you probably can’t breed robust sons either.

Have you ever seen an old-fashioned hairbrush, bristles no rougher than the back of a miffed cat, and wondered what in the world the point of it was? It could not possibly have tamed or styled hair. All it could have been good for was patting your own head in congratulations after a particularly successful mammarial-balm session.

The truth is those brushes weren’t meant to fight tangles or arrange hair in complex designs. For that you’ll need your hard bone, wood, or ivory comb, with a possible touch of pomade, a hair-taming grease used by both sexes. Careful braiding is used to prevent snags, and as for styling, tread lightly, ma petite. A pleasing practical upsweep is about two twists and a curl away from simply wearing a hat that advertises your hourly rate.

The actual hairbrush’s job here is twofold. One, to clean the day’s soot and dirt from your hair at bedtime, because the nineteenth century is filthy. Second, to take the natural grease that your twenty-first-century self shampooed away every day, and distribute it down, down, down, all the way through your long and lusty Victorian mane. Grease is good when your hair is long enough to absorb it all; it provides luster and softness. You might as well tell yourself that, anyway, since washing your hair in the nineteenth century is a rare ordeal.

As for complex hair designs, Victorian ladies experiment with different fancy twists, and they play a bit with their “fringes” (bangs) throughout the century, but mostly you keep that business knotted up tight. And if you are one of those flighty little ninnies who chase fad and fashion, you’ll likely need a bit of “false hair” to help you, i.e., hairpieces made from other women’s locks, affixed to metal frameworks and then stuck into your own updo. Voilà, instant curls, volume, and chignon. The doomsayer Ellington warns that if you must indulge, for heaven’s sake find a reputable hair dealer. The better the class of dealer, the more likely your hairpiece came off a diseased or starving but mostly alive European peasant girl, rather than her corpse.

Donor guaranteed to have survived at least a fortnight after harvesting

Cosmetics: You Might Want to Wait Another Half-Century

In the 1920s, a fellow named Max Factor developed an extremely well-made cosmetic foundation, which he called Pan-cake Makeup. He used it on the movie stars he worked with, so it had to be not only eye-pleasing and smooth (even hand-cranked film cameras were great at catching blemishes) but durable enough not to melt under the hot lights of early filmmaking. The rest is history. Mr. Factor and his knack for cosmetic chemistry are the reasons your grandma could touch up her eyes and lips before church without being treated like Mary Magdalene. Quality makeup is subtle and succeeds in the ultimate goal of making it hard to tell if you’re actually wearing any.

But here we are, many, many years before Mr. Factor. Your makeup is terrible. In catalogs here it is usually listed with the pharmaceuticals or located somewhere between the toothpastes and the dog cleaners. An 1890s Montgomery Ward catalog displays two different brands of “cosmetique” (then as now, French names were used to add mystery to products that had no right to claim any) in three shades: black, pink, and white, which you can blend (somehow?) to create all the different touch-up colors your face needs. In consistency this stuff is similar to extremely greasy, heavy lipstick.

I don’t recommend eyeliner, dear, though it is available in both pencil and paint form, often made from the same stuff as writing ink. I’m simply saying it is near impossible to apply delicately and you’ll look like an ancient Egyptian tart. But if you’re determined, you might as well use all the tricks. It has also long been popular to squirt poison belladonna (deadly nightshade) in the eye. The poison dilates the pupil, giving, according to Ellington, “the upper part of the face a languishing, half-sentimental, half-sensual look.” I imagine that look is probably born of confusion as to why the room has suddenly become so shiny, blurry, and poisonous. “Why is it so bright in here? I don’t feel good. Kiss me!” Some catalogs explicitly say their cosmetics are intended only for the use of thespians, in much the same way modern medical marijuana is dispensed only for the treatment of glaucoma.

Lead: Good Enough for the Mona Lisa, Good Enough for You

You might know that lead, an ingredient used in certain paints and enamels even in the twenty-first century, is poisonous to the human body. That if you are repeatedly exposed to it, either through touch or inhalation, the lead accrues in your blood and tissue, causing nerve damage and death. But did you also know that it leaves the skin with a silky, fine finish when applied in white powder form?

White lead was the popular base of many early cosmetics, long before the nineteenth century. It often traveled under less terrifying names, like sugar of lead or Goulard’s Extract. It was especially prevalent in a process called enameling that was all the rage in the late 1800s. A professional face enameler would remove all possible hair, dirt, and imperfections from his client’s visage and then spread a shiny paste of white lead all over the face, neck, and bust. The result would be rejuvenated, smooth skin whose pores were clogged with both a youthful vivacity and a lethal mineral imbalance. Some sources say the process needed to be repeated a few times a week for true rejuvenation; others say a talented enameler could give you a pasting that would last up to five years, provided you weren’t totally married to the idea of washing your face every day… or month.

Laird’s Bloom of Youth was one such popular enamel. It contained a great deal of lead and was accused of causing a lead-poisoning palsy in its users. Immediately upon this report, around 1870, the makers of Laird’s switched its main ingredient from lead to zinc and began protesting how safe the product was and how cruel the specious rumors of its lead content had been.

Even at the height of its popularity, some people found lead enameling repugnant. An 1872 edition of the Sacramento Daily Union gave a gossipy account of the horrors encountered by two uppity society ladies who thought they could cheat time through chemistry. Oh, but they got what was a’coming to them.

“A lady in Louisville paid $75, we are told, for having her face enameled for the ball given at the Gait House to the Grand Duke Alexis. The enamel was warranted to last three days, and so it did. The lady was taken ill upon her return home from the ball, her face became greatly swollen, the most acute pain succeeded, and it was only by the employment of the best medical aid that her life was saved. This statement we have from an undoubted source.

But the case of this lady is not so bad as that of another Louisville lady who became enamored of the odious fashion of enameling the face[. She] visited another city, far to the eastward, some five months ago, for the sole purpose of having her face enameled according to the latest Parisian mode. She had heard that a noted Parisian was engaged in the enameling business at the city in question, and to him she went upon her arrival. For the sum of $500 he agreed to enamel her face so scientifically that the enamel would remain undamaged for three years, and a year or two longer if extra care was taken in washing the face according to his prescribed method.… The lady received the enamel and returned to this city. Since her return she has disappeared from society. There was so much poison in the enamel that its effects were almost total paralysis of the facial nerves, and what was once a beautiful face is now a distorted and ulcerous one.”

Keep in mind, there were no celebrity tabloids back then, and they didn’t have the catharsis of watching Hollywood housewives crash and burn. Something had to fill the void. So we must forgive the author if she takes a very obvious joy in the necrotized flesh of fellow females.

Of course, people knew lead wasn’t entirely safe, and soon they declared it decidedly unsafe. That wasn’t an opinion shared by everyone. The author of an 1869 book sternly titled Toilet Secrets, known only as Incognita, is quite tired of hearing about how bad lead is for you.

Says Incognita,

“Now, a few words about this said ‘poisoning.’… The practice of crying down everything, wholesale, in the way of ‘lead,’ is just as absurd as if a teetotal lecture is to convince a moderate man he is going headlong to destruction and drunkenness, because he takes his sherry and port, like an Englishman should take it, and like every sensible medical man recommends it.”

Oh, a smidgen of lead rubbed into your sore eyes on occasion can’t be that bad. Incognita is willing to stake her name and reputation on—oh. Well. Let’s move on.

Skin Care: Fire Cleanses All

Freckles aren’t cute in this era. They’re deformities that cry out to the world, “I’m a slack-jawed, unrefined girl who stands in the sun all day with m’cows and m’corn and I don’t know the difference between a soirée and a sodee pop.” So we’ll need to scorch those right off. Many of the lady writers suggest variations of lemon juice, which is still recommended today as a safe way to temporarily fade freckles. But Thomas S. Sozinskey, in his 1877 Personal Appearance and the Culture of Beauty, with Hints as to Character, cuts right through that namby-pamby nonsense.

“Unquestionably the best way of getting rid of them or any other discoloration, when very bad, is to eat them out with muriatic [carbolic] acid slightly diluted, or by applying a blister, or by exposing the face to the sun until it becomes burned sufficiently to be followed by exfoliation of the skin. This last is an excellent remedy and it takes only a few days to effect a cure.”

Granted, the freckles will return because they inhabit a dermal layer deeper than the one you just painfully removed with extreme amounts of ultraviolet radiation. But take heart, so will the sun return! And you can just keep sloughing off layers of your face for however many years it takes to develop either the skin cancer, or the common sense, to slow you down.

You’ll find similar treatments, both prepackaged and home-prepared, for pimples and blackheads (once thought to be facial worms, since squeezing the clogged pore resulted in the excavation of a wormlike deposit). But frankly, if you’re going to be aggressive about these deformities you might as well head straight for the arsenic.

Yes, Dr. Campbell’s “safe arsenic complexion wafers” are among the more deadly poisons known to man, but we can’t make a pure-complexion omelet without breaking a few cerebrovascular eggs.

Wrinkles

Oh, gracious. All this information is taxing you, isn’t it? I see that you’re frowning, trying to process it all. This is why no physician worth his two-year apprenticeship at sea will encourage heavy thought to trample through a female brain. Darling, your frown is causing wrinkles! Wrinkles!

A woman’s face is her introduction to the world, and wrinkles force her to present a shabby and worn calling card! Where do wrinkles come from? Why do they occur? Well, as you might expect, wrinkles are the result of all the things you’re doing wrong.

Do you favor a side when you sleep? According to Beauty: Its Attainment and Preservation, published in 1892,

“Sleeping upon one side will cause wrinkles and crow’s-feet to form about the eyes, and frequently more lines will be seen around one eye than the other. It is advisable, therefore, to sleep upon the back if possible, and if not, to accustom one’s-self to sleeping alternately upon both sides.”

Do you wallow in misery like a sow in slop? Because, as Shoemaker, he of the pineapple breast, reminds us, that is another primary cause of wrinkles.

“A great many people worry themselves into ugliness and foster it by nursing discontent. Keep the blood warm and the well filled with affection and there is no danger of the face shriveling.”

Of course all of that is for naught if you happen to live in one of those putrid wastelands known as cities. Says Shoemaker,

“City people are more afflicted with wrinkles than country people are, and the reason is simply because the conditions necessary to happiness are not as good in the city as in the country.”

To remove these etchings of personal misery and poor sleeping habits, a surprising number of beauty counselors recommend tying meat to your face. Says Lady Montez,

“I knew many fashionable ladies in Paris who used to bind their faces, every night on going to bed, with thin slices of raw beef, which is said to keep the skin from wrinkles, while it gives a youthful freshness and brilliancy to the complexion. I have no doubt of its efficacy.”

These “sleep with something perishable on your face” cures usually involve trying to replace lost fatty tissue, to plump up that which has wrinkled. Various substitutes for your own face fat included: sheep’s wool soaked in sheep’s fat, olive oil, almond oil, beeswax, spermaceti (don’t worry, not what it sounds like; it’s just a gooey waxy substance created inside a sperm whale’s head that early whalers thought looked like semen), veal, and lard. Late-century catalogs pioneered serial-killer style rubber masks to help keep whatever spoiling food you hoped would turn back the clock tightly affixed to your face.

There, now. We’ve got you clean, menstruating with charm, and able to keep your face, hair, and body just as pleasant as sperm whale by-products and unfairly villainized poisons will permit. It is time to go forth armed with your new knowledge, ma petite, and begin the hunt.