FIVE

The Big Idea

Years after leaving Melbourne, Bob Stupak occasionally made trips to Australia to visit his daughter, Nicole, who attended school there. Australia held fond memories for him, and nearly two years after he had warned Melbourne news readers of the problems with legalized casinos, he was back Down Under. This time he was in Sydney with Nicole.

On the way to lunch, Bob Stupak noticed something that would change his life forever.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“It’s the Sydney Tower,” his daughter replied.

They would eat lunch there, he decided. The Sydney Tower, tallest structure in the country, dominated the skyline and held an enormous fascination for Bob Stupak. As they approached the tower, he noticed something else, something that always made him tremble with excitement.

A crowd. A grand tangle of humanity snaked outside the entrance to the tower. What were they doing? Were they actually waiting in line to ride an elevator to the top?

They were, indeed. And they were paying $5 a head for the privilege. Lunch could wait. Stupak had to see for himself. So he stood in line nearly an hour and took in the view from the top.

His plans for building the tallest sign in Las Vegas were scrapped half a world from Vegas World.

The big idea was born.

If thousands of Aussies converged on the Sydney Tower, what might the millions of tourists who visit Las Vegas each year do at a tower and casino?

When he returned to Las Vegas, he set to work learning all he could about the economics and engineering of towers.

His was not the first big idea in Las Vegas history. As early as 1961, Kansas City developer Frank Carroll decided to build a 14-story tower and casino in the shape of the Seattle Space Needle, which was gaining national attention as the centerpiece of the World’s Fair. Carroll quickly decided to raise his Landmark tower to 17 stories, which would make it the tallest building in Las Vegas, a full three floors higher than downtown’s Mint.

Carroll, also known as Frank Caracciolo, had difficulty funding his big idea, but by 1966 managed to coax a $5.5 million loan from the mobbed-up Teamsters Central States Pension Fund for the Landmark, which by then had grown to 31 stories. The Landmark featured a revolving restaurant on the 31st floor and a spectacular view of the valley. Edward Hendricks of Los Angeles was the architect.

By then, it had become obvious that Carroll’s contacts with organized crime were more than casual, and he was denied a gaming license.

Thanks in part to the maneuvering of Howard Hughes aide Robert Maheu, the Landmark was sold to Hughes in 1968 for a whopping $17.3 million. Like other Las Vegas casino acquisitions by the eccentric billionaire, it proved a monumental waste of capital.

Maheu would recall in his memoir, Next to Hughes, that his elusive boss couldn’t even decide when to unlock the place and whom to invite to the grand opening.

“The opening of the Landmark was planned as the most glamorous event to hit Las Vegas in years,” Maheu recalled. “…Although Howard wanted desperately to have a grand party, he didn’t want it to be overshadowed by the opening of the International [now the Las Vegas Hilton, across the street from the Landmark], scheduled for the following day. For weeks, we argued over the opening date, and for weeks we could not agree.

“The absurdity of trying to organize a major event without knowing the date didn’t seem to make any impact on Hughes’ mind.”

Neither did the fact that he paid millions more than the property and building were worth. The 500-room tower opened in July 1969 and struggled from the start. It continued to change hands after Hughes’ Summa Corporation sold it for $12.5 million in 1978. The Landmark lingered in and out of bankruptcy for the next 15 years before the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority purchased it in 1993 for $15.1 million—still less than Hughes’ original price 25 years earlier. On November 17, 1995, the Landmark was imploded to make way for a parking lot.

Stupak planned to avoid the fate of Frank Carroll and the curse of the Landmark. His research would be thorough. He was known as a huckster, a formidable liability in the straight financial world, and anything less than a precise prospectus would doom his plan to failure. There were plenty of precedents to draw from.

Tall buildings had been a part of the American psyche for more than 150 years. They had awed the masses and challenged their builders for generations.

Take the Washington National Monument, for instance. In an attempt to erect a monument worthy of the first president of the United States, the Washington National Monument Society was formed in the mid-1800s. The society hoped to raise $1 million by selling public subscriptions to the tower project for $1 apiece. Americans loved George Washington, but after four years the society had managed to scrounge up just $25,000.

The Washington Monument languished as an embarrassing stump in the nation’s capital until 1876, when it was completed in time for the centennial of the American Revolution. At 555 feet, it was the world’s tallest hunk of masonry.

Surely the Eiffel Tower, built for the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889 to celebrate the centennial of the French Revolution, was the most famous tower of the 19th century. It remains one of the most recognized structures in the world and is one of the few great towers named for its designer, Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel, who also designed the Statue of Liberty.

The 984-foot structure, which was built at a cost of $500,000 and designed to be dismantled at the end of the exhibition, was immediately condemned by French artists and intellectuals as a monstrosity, too mechanical looking to be classified as great architecture.

It was all too grotesque to be French, its detractors shouted. Among the most vocal critics were novelists Alexandre Dumas Jr. and Guy de Maupassant, the latter of whom was so disgusted by La Tour Eiffel that he ate lunch at its restaurant as often as possible for the pure pleasure of not being forced to look at it on the horizon.

But the people loved it, and no one dared touch a rivet to harm it.

“If La Tour was an insult to the representatives of the ‘effete class,’ it was love at first sight for the people,” Mario Salvadori wrote in What Makes Buildings Stand Up: The Strength of Architecture. “Two million of them flocked to visit it during its first year. More than half of them reached its top. Thousands climbed the 1,671 steps before the elevators were open to the public. The crowds increased even long after the exhibition closed and, slowly but surely, their visits acquired new meanings. They went to look at the Tower as much as to look from it, to look inside, at its filigree of steel, as much as to point out the other monuments of their city. It became the symbol of Paris, the Mecca of all travelers, visited by far more people than Notre Dame or Sacre Coeur. And then it became, somehow, the symbol of France.”

Could Bob Stupak with his eighth-grade education and questionable reputation be the man who changed the way Americans looked at Las Vegas by building a tower?

The Eiffel Tower also opened a new chapter in structural engineering. It was made by a mere 250 workers from 7,000 tons of wrought iron and 12,000 prefabricated pieces, and held together with 2.5 million rivets. Its cross-braced lattice structure gave it maximum wind resistance; it moved just nine inches in hurricane-force winds. So geometrically sound was the structure that it applied no more pressure on the ground than that of a person sitting on a chair, Salvadori wrote. It was a financial steal at a half million dollars and was completed in a little more than two years without the loss of a single life.

It also attracted visitors from around the world and was the source of countless news articles whenever someone attempted to climb it or fly an airplane through its arched legs.

Bob Stupak was beginning to dream big. And as he continued his research, he grew even more excited.

New York City has been the proving ground for America’s tallest structures. It is the place where the skyscraper got its name. Manhattan’s first impressively tall building was not a behemoth office giant, but the 350-foot Latting Observatory. Constructed of wood, it was completed in 1853.

In 1902, the Fuller Building, at 300 feet, became the world’s tallest inhabitable building. It was soon forgotten after William Van Alen designed what would become known as the Chrysler Building. Heavily influenced by the Jazz Age, and the first building taller than the Eiffel Tower, the Chrysler stood 1,048 feet high and was completed in 1928.

The Empire State Building was more than a skyscraper. It emerged as a symbol of the strength of the American spirit during the Great Depression. The 85-story building, designed by Shreve, Lamb and Harmon, was constructed of 200,000 cubic feet of Indiana limestone at a cost of $52 million. In all, 57 tons of steel went into the building, which, including its 200-foot spire, stands 1,250 feet. It took less than one year to build.

The Empire State Building was designed and constructed as a mountainous office complex, but when it opened in May 1931 its developers made a killing off its impressive size. According to John Tauranac’s The Empire State Building: The Making of a Landmark, “The gate for the ordinary, everyday view would have pleased a Scrooge. By the middle of November, the observatories were averaging 2,200 visitors a day, and had brought in $698,554. In the first year, a total of 775,000 visitors provided a gross income of $875,000 for the observatories, including the profits from ticket sales and the sales of souvenirs and refreshments to visitors. At that rate, the building was grossing about two percent of the building’s construction costs every year.”

Whether in the form of the 1,350-foot World Trade Center in New York or the 1,454-foot Sears Tower in Chicago, modern cities of any importance have a skyline to match their ambition. Towers appeal to the societal ego of modern Western civilization, and a Las Vegas tower was beginning to appeal to Stupak’s sense of hyperbole.

“Las Vegas and Versailles are the only two architecturally uniform cities in Western History,” Tom Wolfe wrote in 1965 in The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby.

“Las Vegas was the only city of its kind to be seen on this scale of thoroughness,” Alan Hess wrote in Viva Vegas: After-Hours Architecture. “To call it untraditional would be an understatement; it was generally considered an urban freak, in thrall to the gigantic and the garish.”

And what could be more freakish, fun, and financially feasible than a Las Vegas tower?

Toronto’s 1,815-foot CN Tower, the world’s tallest self-supporting structure, was completed in April 1975 after a little more than two years of construction. Built at a cost of $63 million, the 143,000-ton structure was made of reinforced post-tensioned concrete and included a revolving restaurant at the 1,150 mark.

Not only is the CN Tower a tourist attraction, but it helped spur an impressive development in the area. Today, a major league baseball stadium has sprung up nearby, and it continues to serve as a marketing and development centerpiece of Toronto and eastern Canada.

But nowhere in North America has a tower made more of an impact than in Seattle, where the Space Needle has long since become the central identifying image in the city’s skyline.

Modern marketers have portrayed the Space Needle not as a restaurant or tourist attraction, but as a national landmark. Make that a national landmark generating millions in retail sales on everything from T-shirts to gourmet coffee. The national landmark attracts 3,000 people a day, or approximately 1.2 million per year, and has become a favorite location for New Year’s Eve celebrations. Like a sports franchise or celebrated athlete, the Space Needle is so popular it collects fees for corporate sponsorships from Coca Cola, Mars, Eastman Kodak, and Boyd Coffee.

Beyond the symbol, the Space Needle’s revolving restaurant is the 12th busiest eatery in America. To Stupak, the Space Needle embodied the powerful economic potential of observation towers.

Surely a Las Vegas tower would do at least as well. And with plenty of slot machines and table games strategically positioned at its base, there was no telling how much money Stupak’s big idea might be able to generate.

The Seattle Space Needle had something else in common with Stupak’s dream: a surprisingly similar location.

“Those working to rejuvenate downtown Seattle envisioned a compact, centrally located business district that would become both more built up and more attractive to pedestrians and shoppers,” John M. Findlay wrote in Magic Lands. “Planners for downtown Seattle hoped to provide freeway access as well as plentiful parking and pedestrian landscaping. They also intended to attract new businesses and cultural activities that would help the downtown withstand the threat of suburban growth; to develop a public transit system that might forestall traffic congestion; to stimulate urban renewal in order to minimize blight.”

Which is precisely what Las Vegas dreamers had been attempting to accomplish with their fortune-squandering downtown redevelopment projects, ill-conceived Fremont Street attractions, and heavy-handed use of eminent domain.

For the site of the tower, Seattle planners chose the Warren neighborhood. It was in several respects much like Naked City.

“Although hardly a slum, the Warren neighborhood had a higher crime rate than the rest of Seattle, more unemployment, fewer owner-occupied homes, a higher percentage of older, less valuable housing, more elderly residents, lower average incomes, and fewer families and school-age children,” Findlay reported.

If the history of the Space Needle was any barometer, a downtown Las Vegas tower would affect a lot more than Stupak’s business interests.

“The need for financial success weighed heavily on the businessmen who promoted the 1962 fair,” Findlay wrote. “Yet proposals to import nude showgirls from Las Vegas and Paris, as well as to repeal local blue laws for the duration of the exposition, lent credence to the charge that fairs catered to the lowest common cultural denominator.”

The fact that Stupak planned to build his tower as a hook to fleece the millions of tourists who sojourned to Las Vegas each year was beside the point.

It is important to note that venues for the performing arts and big-league sports grew out of the success of the Space Needle and the fair. The Space Needle quickly came to symbolize Seattle the way Disneyland defined Los Angeles.

A lot had changed since Stupak’s original plan to build a 320-foot sign to advertise Vegas World. In October 1989, he announced his intention to build a 1,012-foot observation tower next to Vegas World.

“What I’m trying to do for Las Vegas is what the Eiffel Tower did for Paris, what the Empire State Building did for New York, what the Space Needle did for Seattle,” Stupak said.

He asked the city Building and Safety Department to put on hold plans he’d submitted for a neon sign four times as tall as Vegas World. Then he quickly began redrawing his big idea to include an elevator and observation deck.

Stupak’s detractors on the City Council immediately moved to block approval of the plans by passing an ordinance limiting the height of signs within the city limits, but the move was so painfully obvious that it died in committee. The so-called “Stupak Ordinance” faded rapidly.

In keeping with Vegas World’s outer-space theme, Stupak would add laser lights to his tower, which now had a price tag, $30 million, and a tentative completion date, New Year’s Eve 1990. That gave Stupak a little more than a year to bring it all together. If the Empire State Building could be constructed in a year, so could Stupak’s tower.

“My daughter was living in Australia, and I went to visit her. We had lunch at the Sydney Tower. That’s a 1,000-foot tower with a revolving restaurant on top. … That gave me the spark of an idea. We’re building this sign. Maybe I should put an observation deck at the top.

“Then we said, ‘Well, maybe we can make it go a little higher.’ Then we started fiddling with the tower and, after a while, forgot about the sign. And 1,000 feet high seemed like the right number. I made it 1,012 because it seemed like a more scientific number.

“The Eiffel Tower was 984 feet, and everybody was familiar with that, so I figured we had to be taller than the Eiffel Tower.”

By 1990, gaming consultant Howard Grossman had left Stupak’s employ, but he enjoyed dropping by Vegas World to listen to the city’s foremost pitchman. That’s where he first heard about the tower.

“I went into Vegas World one time to visit somebody there who was working for him and ran into Stupak,” Grossman recalled. “I asked him about the tower. I figured it was another of his crazy ideas.

“He knew all about towers. He said every tower in the world makes money. He believed that he would have probably a couple million people a year coming through the tower. It would bring him business and I never doubted him.”

As a last reality check before running headlong into the project that was sure to make or break him, Stupak contracted with Arthur Andersen & Co., a national accounting firm, in an attempt to double-check his theory. Its numbers crunchers were impressed by what they saw.

“They came back with even bigger numbers, and I said, ‘This is too good to be true,’” Stupak told a reporter. “I figured, ‘To hell with casinos in Vegas, I’m going into the tower business all over the world.’

“I wanted it to be bigger than the Eiffel Tower in Paris, bigger than the Space Needle in Seattle. The CN Tower in Toronto is 1,815 feet tall, and I wanted it to be bigger than that.”

And so the Stratosphere Tower was born.

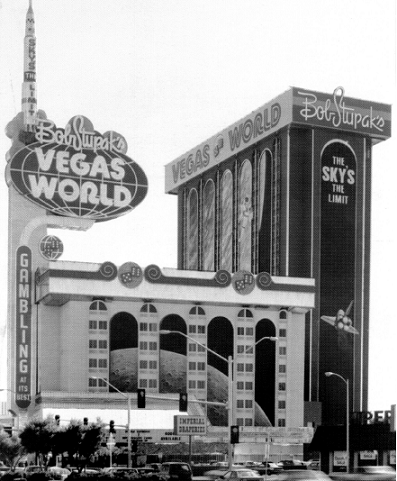

At Vegas World, Stupak’s motto always was “The Sky’s the Limit.” For all his shortcomings, he had gained a reputation as a man who, given the proper circumstances, would fade any bet. More than a slogan, it was his life’s philosophy.

The financing and construction of his dream tower were about to test his philosophy to the breaking point.

Vegas World. The sign on the left eventually evolved into the 1,149-foot Stratosphere Tower.

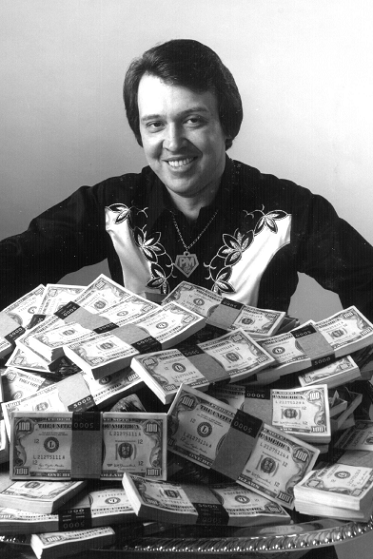

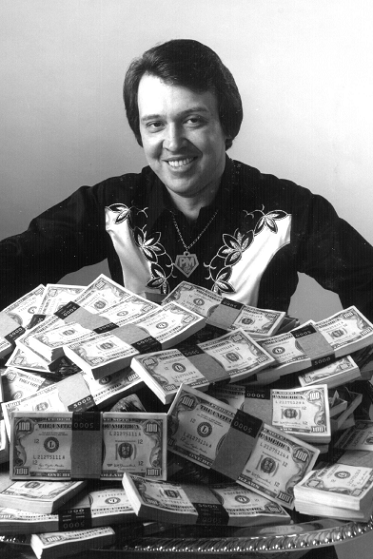

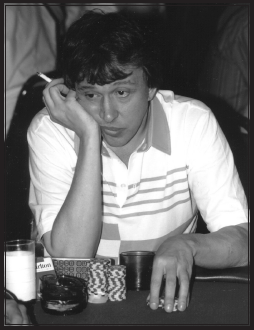

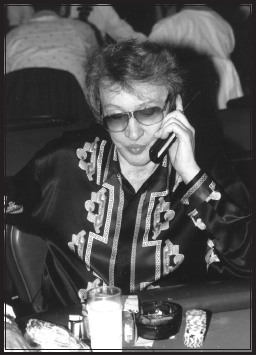

Bob Stupak in marathon no-limit poker games—before and after the motorcycle accident. (Larry Grossman)

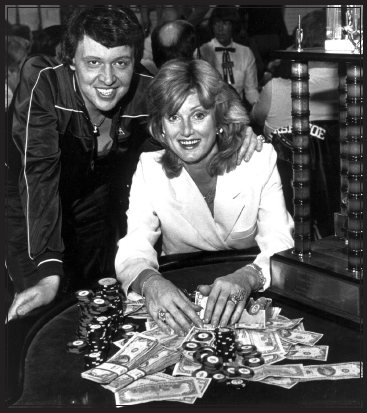

Australian Sandy Wilkinson Stupak celebrates with her husband after winning a celebrity poker tournament.

from left: Summer, Bob, and Nevada Stupak

Phyllis McGuire lent some class to Stupak’s later years. (Jeff Scheid/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Bob Stupak’s lifelong love affair with motorcycles nearly killed him.

Though Frank Sinatra befriended Stupak, he never appeared in Vegas World’s Galaxy Showroom.

Who gets less respect—Bob Stupak or Rodney Dangerfield?

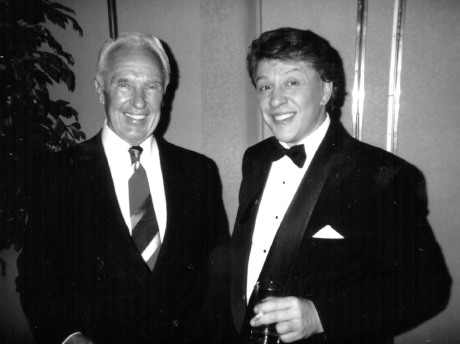

Bob Stupak with the banker who built Las Vegas, E. Parry Thomas.

Las Vegan Debbie Reynolds, and billionaire Kirk Kerkorian (below).

Nicole Stupak’s performance in a pre-election debate with opponent Frank Hawkins proved her undoing in the 1991 City Council race. (Jim Laurie/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Politics—Bob Stupak ran for mayor of Las Vegas twice and lost.

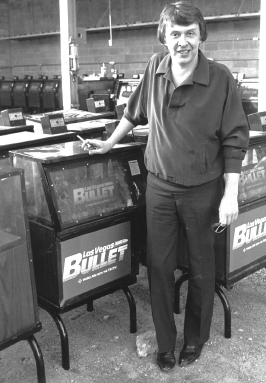

And publishing—His alternative weekly newspaper, the Bullet, lasted 18 months. (Wayne C. Kodey/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

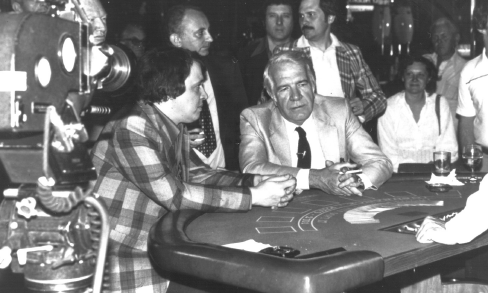

Stupak promoted his out-of-the-way casino on “60 Minutes” with Harry Reasoner.

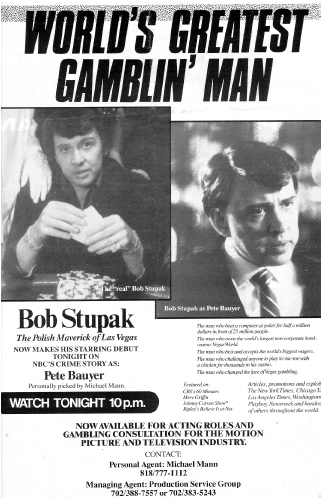

Stupak promoted himself with a full-page ad in Variety announcing his juicy cameo on “Crime Story.”

Dan Koko leapt from the top of Vegas World into a protracted legal battle over jumping and landing fees. (Rene Germanier/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

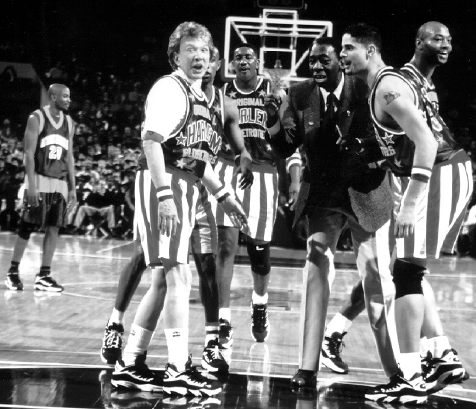

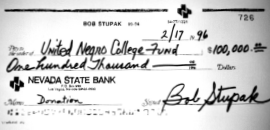

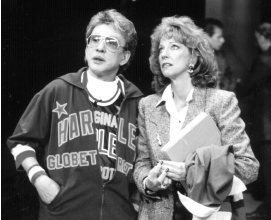

To fulfill a lifelong dream to appear with the Harlem Globetrotters on the floor of Madison Square Garden, Stupak donated $100,000 to the United Negro College Fund. Among his entourage was Las Vegas Mayor Jan Jones.

Among his entourage was Las Vegas Mayor Jan Jones.

The derogatory moniker “Stupak’s Stump” gave way to “Stupak’s Roman Candle” during the brief but spectacular blaze at 510 feet. (Jeff Scheid/Las Vegas Review Journal)

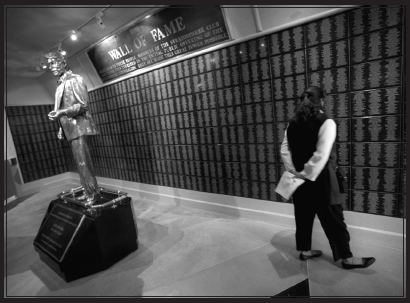

Gilded statue of Bob Stupak in front of the Stratosphere “Wall of Fame.” (Jeff Scheid/Las Vegas Review Journal)

Grand Casino’s Lyle Berman. (Larry Grossman)

Big shot Bob Stupak on Stratosphere’s Big Shot, highest thrill ride in the world. (Jeff Scheid/Las Vegas Review Journal)