3: HOW DO ADULTS LEARN?

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Distinguish between pedagogy and andragogy and explain the implications of this categorisation for your style and practice as a trainer

- Explain the different metaphors you can use to describe your role in the training process

- Explain how thinking has changed about how adults learn and its implications for your practice as a trainer

- List the characteristics of the learner and the needs of the adult learner

- Describe the laws of learning and their application for the training programmes you design

- Explain the concept of learning styles and their relevance for the training methods and practices you use

- Explain some of the misconceptions about the adult learning process

- List the main conditions that facilitate effective adult learning.

INTRODUCTION

Learning lies at the heart of training and development. Whether you adopt a formal and systematic learning process or a more informal and ad hoc approach, learning is a necessary pre-condition for anything that you wish to achieve.

To learn is to gain knowledge or skill in a particular area. You will find that many trainers use the terms “competence” and “capability” to express the objective of learning. They often say things like “I want to be competent in a job role” or “to possess the capability to carry out certain activities to the highest standards”. This type of discussion places an emphasis on the results rather than on the change process of learning.

We are concerned in this chapter with the process of learning. We focus on the philosophical aspects of learning, in addition to the characteristics of adult learners, and the more important learning “laws” that you should be aware of as a trainer. We believe that it is important that you have a basic conceptual grasp of what learning is and why it is central to your effectiveness as a trainer.

PHILOSOPHIES & METAPHORS OF LEARNING

We first consider some of the philosophies of learning. We explain three metaphors that are commonly used to describe the learning process. If you fully understand the learning process, it will help you design more effective T&D activities.

Understanding Learning Philosophy

The two primary learning philosophies are: Pedagogy and Andragogy.

Pedagogy

Pedagogy is derived from the Greek words “ped”, meaning “child”, and “agogus”, meaning “leader of”. Therefore, pedagogy literally means the science of leading (teaching) children. Historically, from the Middle Ages to the 20th century, the pedagogical model was primarily used to teach.

Pedagogy represents the traditional, most frequently implemented and trainer-centred approach to learning. It is based on a number of important assumptions:

- You make all the decisions about the learning process and the learner is a submissive receptacle

- The learning is standardised and progressive because it is aimed at a group of learners uniform in terms of age and experience

- The training activities you implement are subject-oriented. There is a strong emphasis on subject matter content

- The learner brings little experience to the learning situation. The learner is essentially dependent and inert

- Lectures and formal inputs are the backbone of the pedagogical approach. The pedagogical approach is now considered less appropriate in the adult learning context, although it may have relevance depending on the subject matter.

Andragogy

Andragogy is described as “the art and science of helping adults learn” and can be viewed as the antithesis of the pedagogical approach. Knowles’s model is the backbone of this philosophy and is based on the premise that, as an individual matures, the need to be self-directed, to have opportunities to use experience in the learning process, to be active and to participate in organising and structuring the learning process all develop.

If you wish to implement an andragogical philosophy in your training, you need to be concerned with the following androgogical assumptions:

- The Desire to Know: Adults need to know why they need to learn. Adults have a keen desire to establish “What is in it for me?”, before they invest in the process. You need to emphasise the importance of the training event in terms of improving the effectiveness of the learner’s performance to their jobs and lives

- The Need to be Self-Directed: Adults like to be responsible for themselves and may resist situations where they are being forced to learn. Trainers need to empower learners to enhance their skills and abilities and nurture this self-directed need

- The Need to Build on their Experience: Adults have developed experience over many years, which needs to be tapped using appropriate learning methods. These methods include:

- Group discussion

- Role-plays

- Case studies

- Problem-solving activities

- Action learning.

A group of adults will learn much more from each other than they would from listening solely to a trainer. On the other hand, adult experience can be viewed as negative, as we can develop biases that can inhibit our ability both to change and to develop new ideas. This can sometimes manifest itself in the training room.

If you are to successfully implement the androgogical model, you need to be concerned with clearly diagnosing the needs of your learner, and involving them in the formulation of the learning objectives and the design process.

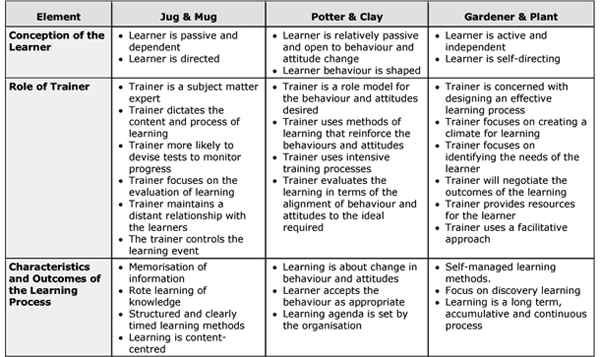

Figure 3.1 presents a comparison of pedagogy and andragogy.

FIGURE 3.1: COMPARING PEDAGOGY & ANDRAGOGY

We do not present these two categories of philosophy as representing good/poor training practice. They are best viewed as approaches to training to be considered in terms of their appropriateness for particular learners in particular situations. If pedagogical assumptions are realistic in a particular situation, then pedagogical strategies are appropriate. For example, if a learner is entering into a totally new content area, there will be a strong dependency on a trainer, until enough content has been acquired to enable self-directed inquiry to begin.

A significant amount of current training practice is based to a certain degree on the philosophy of andragogy. If you wish to implement an effective andragogical approach to training, you need to be aware of the following implications for your style and approach as a trainer:

- Motivation of the learner is an intrinsic process. Your role as a trainer is to create a learning environment that captures these intrinsic drives

- Self-directed learners might need your support. Your role is to recognise when this need exists and to provide the appropriate support

- Whenever possible, you should tap into the experience of each learner. Knowles would argue that “to deny a learner’s experience is to deny the learner”

- Participative learning methods are more appropriate because they use the learners’ experience to the benefit of others; they also ensure that the learner’s span of attention is widened and that more learning takes place

- The content of the training programme should be a contract between you and the learner. This helps to meet the learner’s needs for relevance

- Where you decide to impart knowledge to learners in a passive manner, you should provide ample opportunities to reinforce the learning by varying the methods that you use.

Some Metaphors to Explain the Learning Process

We suggest that there are three metaphors of learning that may be of value to you in seeking to understand your role in the learning process. Knowledge of these metaphors should enable you to clarify the purpose of the learning activity, your role within the learning process and the role that the learner is expected to perform.

- Jug and Mug: The “jug and mug” approach to training is essentially a pedagogical approach. You, the trainer, are viewed as the fountain of knowledge, the subject matter expert. Your task is to transfer your knowledge and experience to the trainee, like a jug (the expert) filling the mug (the trainee). Rogers described this approach as the traditional trainer-centred approach. If you adopt this metaphor, you will be expected to develop a detailed programme of learning and follow it strictly. Your trainees will have limited involvement and are generally not expected to question the content. Your learners are required to digest information and memorise it. It is a good idea to use this approach when you engage in training activities related to explaining policies and practices of the organisation – for example, it can be used in induction training and elements of operator training, training on health and safety and quality

- Potter and Clay: A “potter and clay” metaphor is concerned with shaping the behaviour and attitudes of your learners. It is a metaphor that you are likely to use in many modern training activities. For example, if you are training in safe working practices, total quality management or customer service, your role as trainer is to shape the learner’s behaviour and ensure that their attitudes are in line with the values espoused by the organisation. This metaphor is linked to the Jesuit maxim: “Give me a child before seven years and I will train him for life”. It is possible to consider this metaphor as a form of brainwashing, in that you know what is best for the trainee and you set out to achieve it. Part of this modus operandi requires you to use methods that reinforce the message you seek trainees to take on board and to demonstrate behaviours consistent with the behaviour you wish trainees to demonstrate

- Gardener and Plant: The “gardener and plant” metaphor is learner-centred, where you take on the role of facilitator. Your task here is to assist, realise, enable and promote the natural potential for learning that the trainee possesses. You empower the learner, develop their growth potential and allow them to reach their potential. You share responsibility for learning with the learner and your task is to encourage a climate of continuous development through experiential learning. This type of learner-centred learning will lead to significant, lasting and pervasive learning because the learner is involved. In this way, the learner will learn the process of learning, as well as the content of learning.

Figure 3.2 presents a summary of the main features of each metaphor.

FIGURE 3.2: CHARACTERISTICS OF THREE TRAINING METAPHORS

CHANGES IN THINKING ABOUT THE LEARNING PROCESS

It is clear from what we have discussed so far in this chapter that our thinking about the learning process has changed in the last 20 years. When we think about the learning process, we usually focus now on both the processes and outcomes of learning.

Processes

We define the process by which people learn as the way learning takes place. We can use the terms “approaches to learning” or “methods of learning” to describe the types of decisions that you will be required to make when you design training activities.

However, the term “process” has another meaning. It can refer to the internal process that a learner experiences during learning. We have a lot yet to learn about this internal process, although we do know that experience leads to learning. We will say more about this a little later.

Traditionally, we considered that learning took place in a structured manner and that people could only be instructed or taught. Our more holistic and comprehensive view of the learning process shows that people can learn in six different ways:

- Learners can be taught: This is a typical “jug and mug” approach and is associated with the use of a narrow range of methods under the control of the trainer. It involves rigid roles for both the trainer and the learner and usually involves the learning of knowledge and the imparting of information. This approach is potentially problematic where the trainer does not have effective training skills

- Learners can be instructed: This is similar to the first approach, although it is associated with psychomotor rather than cognitive skills. It generally involves a learner being shown what to do, with supporting explanations about how to do it. There is significantly less uncertainty about the learning outcomes. Again, success depends on the skills of the instructor/trainer

- Learners can experience: Learners can learn through new experiences and challenges. The key challenge for organisations is to provide a variety of experience that is relevant to the job and to structure the processes so that learning is predictable and effective for both parties

- Learners learn from trial and error, failure and success: This learning process is not subject to control or structure. The learner experiments and may make mistakes, which are regarded as learning opportunities. The learner may also have successes from which they learn

- Learning can be based on observation and perception: This is a natural and important part of the learning process. It is an incremental learning process and involves the learner making sense of the world through “seeing” things in a particular way and giving meanings to what is “seen”.

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge of what learners are supposed to learn, and ensuring that it is known and understood, are vital components of the learning process. Two types of learning outcomes are relevant:

- Vertical: Learning how to do what the learner can already do, better, differently or to a higher standard. We can label this as vertical learning because the learner is simply increasing or building on a current level of competence

- Horizontal: Learning to do something new or different from a learner’s existing capabilities. We describe this as horizontal learning because the learner’s view of the world is being extended.

Many learning situations are a combination of both types of learning and the relative emphasis given to each one will vary depending on the objectives of the learning process.

We now have a more integrated notion of the learning process. Research points to significant changes in our thinking about learning. These changes in assumptions about the learning process are summarised in Figure 3.3.

FIGURE 3.3: HOW RESEARCH HAS CHANGED OUR ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT THE ADULT LEARNING PROCESS

UNDERSTANDING LEARNING THEORIES

We now focus on some of the main laws and theories of learning that are relevant to you, as a trainer, and which will inform your training style and activities.

Laws of Learning

Psychologists have identified certain influences, commonly referred to as the “Laws of Learning”, which can either help or hinder the learning process:

- The Law of Intensity states that the rate of learning is more rapid when material is organised into meaningful relationships. This has important implications for the way you sequence training content

- The Law of Contiguity in a learning situation refers to nearness in time. For learning to take place, for example, the associated learning event must fall within a certain time limit

- The Law of Exercise means that the trainee is exercising what has been learnt. For example, performing a skill in conditions favourable to learning tends to improve subsequent performance. In simplistic terms, the learner is practising what has been learnt; this is termed an “exercise” by psychologists

- The Law of Effect states that a response leading to a satisfying result is likely to be learned, whilst a response leading to an unsatisfying result is likely to be extinguished. The idea of satisfaction goes beyond mere pleasure. For example, to be satisfying, the result must fulfil some need or motive of the individual in the learning situation. In this sense, some psychologists refer to this learning as reinforcement rather than the law of effect. It is important to note that some unsatisfactory consequences of learning can be as effective as satisfactory consequences if they are vivid, novel, or striking

- The Law of Facilitation and Interference occurs where one act of learning assists another act of learning – for example, if some stimulus in the new situation needs a response already associated with it in the old situation. However, it will hinder the new act of learning if some stimulus, which needed one response in the old situation, needs a different response in the new situation.

The application of laws are referred to as conditioned learning.

Silverman’s Nine Principles of Learning Theory

Silverman (1970) formulated nine core principles of learning. He summarised them in this way:

- Learners learn from what they actively do

- Learning proceeds most effectively when the learner’s correct responses are immediately reinforced – effective feedback

- The frequency with which a response is reinforced will determine how well the response will be learned

- Practice in a variety of settings will increase the range of situations in which learning can be applied

- Motivational conditions influence the effectiveness of rewards and play a key role in determining the performance of learned behaviour

- Meaningful learning (learning with understanding) is more permanent and more transferable than rote learning, or learning by some memorised formula

- People learn more effectively when they learn at their own pace

- There are different kinds of learning and these may require different training processes.

Kingsland’s Approach to Learning

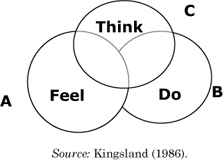

A further approach to learning was developed by Kingsland, based on his theory that learning is a combination of cognitive (thinking), affective (feeling) and behavioural (doing) components:

- Cognitive learning is related to aspects of behaviour, which we might call “insight”. So cognitive learning is concerned with various aspects of knowing, such as perception, memory, imagination, judgement, reasoning and problem-solving. There is a close relationship between cognitive theories and “discovery” learning, whereby trainees are set tasks that involve searching for and selecting stimuli on how to proceed

- Affective learning concerns the involvement and response of individuals within the learning process so that they perceive the interaction as being conducive to their commitment. In organisational terms, this type of learner becomes involved in an ongoing informal exchange of feelings between all other individuals involved in the learning process, such as the learner’s supervisors, as well as external customers

- In characterising human behaviour, it is conventional to refer to it in terms of stimulus and response. The stimuli are very often external to the individuals, but they may also be internal. For example, the external stimuli could be very definite, such as the changing of a traffic light. Subtle stimuli might only be discerned or picked up by those especially attuned to them – for example, a manager’s tone of voice. An example of internal stimuli could be where the completion of one operation or a particular job or task triggers another. For example, an accountant’s duties might involve a sequence of tasks, one automatically following the other.

In terms of conditioned learning, these three faculties correspond with associating new experience and data primarily with ideas, patterns and structures (cognitive); with human contexts (feeling); or with physical responses and actions (behaviour). Individuals will have all three patterns of association, but in varying degrees.

ADULT LEARNING STYLES

Kingsland’s Personality Spectrum

Kingsland developed a personality spectrum that illustrates the learning styles of individuals with the overlapping of feeling, doing and thinking. He refers to these areas simply as A, B or C. In the case of a particular individual, a small amount of one of these attributes would be represented by lower case a, b, c.

This spectrum is further developed to produce seven combinations or different styles of learning: reactive, proactive, holographic, adaptive, communal, functional and molecular.

- Reactive: The stimulus for the reactive or activity style is typified by action-based learning, with perhaps numerous trials. Reactive learning can also take place where there is a need in an organisation for immediate action to be taken and the individual learns as the task is carried out. This style of learning can also be supported by practical instruction of some kind. The more formal development of the employees within this context must involve training activities that stimulate the learners both physically and mentally, in every respect.

- Proactive: The learners thrive on tough business games that are perceived as a challenge. They are highly “energised” to learn and seek challenging projects that lead to the successful identification of opportunities. In an organisation, this identification would be of opportunities for the business as a whole. The learning event must, therefore, be highly “charged” and be behaviourally and emotionally challenging, because learning for this type of learner must be highly demanding in every way.

- Holographic: These learners are inspired by their need for self-actualisation and may be regarded by others as visionaries. They may project a powerful image, because they strive to change or transform an organisation and to adopt an innovative approach to all work-based activities. A T&D event would have to be inspirationally demanding and relevant, otherwise it would not be regarded as necessary by this learner and, consequently, the transfer of learning would not occur

- Adaptive: This is learning by experiment and is different from reactive learning. Employees should be actively encouraged to learn by experiment on an on-going basis. The learner’s style consists of experimentation with new ideas and methods for procedures, assessing how they work and, therefore, learning from the results of the experiments. These learners very often assist an organisation in adapting to rapid changes, as they need the changing circumstances to allow them to experiment. This, in turn, helps the organisation to implement change. A learning event must be varied and provide opportunities to experiment with an appropriate work-related problem so that the learner can present, and relate to, tangible outcomes

- Communal: Responsive learners within communal learning are those who become actively involved not only in their own development, but also that of other learners, managers and the organisation itself. Such learners are motivated by small group activities where the learning can be shared and where myths and stories about the organisation can be recited. The purpose of these myths is to retain the “identity” and external perceptions of the organisation’s standing and value to the general public. Communal learners need to have a “sense of belonging” and they are caring and sympathetic if difficulties arise in the learning of their peers. These learners appreciate coaching and mentoring from other “like” individuals who have a caring or people-oriented approach to human resources, rather than a market-led or market-oriented approach

- Functional: This style of learner acquires knowledge or skill in a methodical or deliberate manner, where the learning event is pre-determined or prescribed on a formal basis. The learner is content to be trained systematically, where the learning event is regarded as a short sharp injection of training rather than being developed on an on-going basis. This shorter event provides an opportunity for the learners to acquire specialised expertise, but on a de-personalised basis. An organisation with a bureaucratic structure, functional delineation areas, changes occurring infrequently and which is formal and predictable would be suitable for this type of learner

- Molecular: The learner here flourishes as an interventionist who is interested in focusing on areas that will be of mutual benefit to individuals, groups, departments and to the organisation as a complete holistic entity. These learners must be provided with learning events that lead to positive outcomes, because they like to create synergy both within and outside the organisation – for example, by developing and learning from productive experiences with the organisation’s direct suppliers and customers for the benefit of everyone involved. This can help to protect the organisation’s survival and ensure its growth.

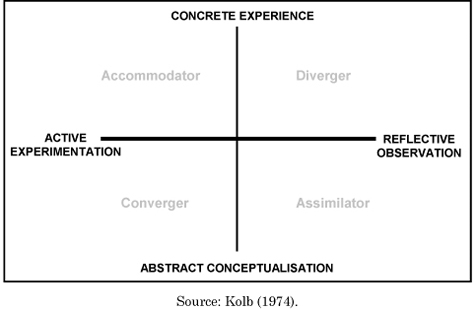

Kolb’s Learning Style Theory

Kolb formulated a theory of learning by identifying four learning styles and arranging them into a model. His contribution to researching learning styles did not end with this model; he also analysed the different types of learners. Kolb postulated that a learner’s dominant learning styles is the result of “our hereditary equipment, our particular past experiences and the demands of our present environment”.

He identified four learning styles, defined as:

- The diverger combines concrete experience and reflective observation and can consider situations from many perspectives. This style characterises many human resource managers

- The converger combines abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation and favours the practical application of ideas. This style is often found amongst engineers

- The assimilator combines abstract conceptualisation and reflective observation and has strength in inductive reasoning and creating theoretical models. This type of learner can be found in research and planning departments

- The accommodator combines concrete experience and experimentation and is a risk-taker who excels in carrying out plans and experiments. This type of learner characterises many of those who work in marketing or sales departments.

An important development of Kolb’s (1979) work is the Learning Style Inventory (LSI), which he describes as “a simple self-description test, based on experiential learning theory”. It is designed to measure the learner’s strengths and weaknesses as a learner in each of the four stages of the learning processes:

- Concrete experience

- Reflective observation

- Abstract conceptualisation

- Active experimentation.

The objective of the questionnaire is to help individuals to identify their dominant “learning style” – the way that they go about solving problems.

According to Kolb, the four stages can be combined to form two major dimensions of learning: first, a concrete/abstract dimension, and second, a reflective/active dimension. Results can be logged on a chart incorporating these two dimensions, and a dominant learning style is allocated to each quadrant, as shown in Figure 3.4.

FIGURE 3.4: KOLB’S LEARNING STYLES CLASSIFICATION

Honey and Mumford’s Learning Styles

Honey and Mumford (1995) also researched learning styles, basing much of their work on Kolb’s ideas. They refined Kolb’s categories and used them to profile the type of trainee (identified by learning style) most likely to benefit from certain types of learning situations. Honey and Mumford propose the following learning styles:

- Activists: Enjoy the here and now; dominated by immediate experiences, they tend to revel in short-term crisis and fire fighting activities. They thrive on the challenge of experiences but are relatively bored with implementation or longer-term consolidation. Activists are the life and soul of the party

- Reflectors: Like to stand back and ponder on experiences and observe them from different perspectives. They collect data and analyse situations before coming to any conclusions. They like to consider all possible angles and implications before making a move, so they tend to be cautious. Reflectors enjoy observing other people in action and often take a back seat

- Theorists: Are keen on basic assumptions, principles, theories, models and systems thinking. They prize rationality and logic ability, and tend to be detached and analytical and are unhappy with subjective or ambiguous experiences. Theorists like to arrange disparate facts into coherent theories, and tidy and fit them into rational schemes

- Pragmatists: They positively search out new ideas and take the opportunity to experiment with applications. They are the people who return from courses brimming with new ideas that they want to try out. Pragmatists respond to problems and opportunities “as a challenge” (activists probably would not recognise them as problems and opportunities).

The learner’s preferred style has important implications for the kind of learning methods and approaches that you adopt. This is particularly important because for example we know that activists and reflectors learn best in one-to-one instructional situations whereas pragmatists learn best from coaching programmes.

Activists learn more easily when they can get involved immediately in short “here and now” practical activities and when there is a variety of things to cope with; they are not put off by being “thrown in at the deep end”. Activists do not learn well when they are required simply to observe and not to be involved or when they are required to listen to theoretical explanations. Highly-structured massed practice sessions, such as where an activity is practised over and over again, would also not be liked by the activist.

On the other hand, reflectors learn best when they are allowed to watch, observe or listen and then think over or review what has taken place. They certainly need to “look before they leap” and to be given plenty of time for preparation. Being “thrown” into situations without warning would lead to an adverse reaction from reflectors.

In coaching situations, pragmatists need to work with activities or techniques that have an obvious practical “pay off”; they must concentrate on practical job-related issues. For the pragmatist, the content of the coaching session must not be theoretical but clearly related to their own reality.

An individual’s learning style preference can be assessed in a reasonably objective way by means of a questionnaire, preferably administered prior to the beginning of any training interaction coaching sessions. The benefits of this data for you as a trainer are that:

- It will help you to design training events that fit in with the predominant style of the trainees

- If the results of the questionnaire are “fed back” to learners, it can help them to appreciate the difficulties they might experience with particular training methods that, out of necessity, may have to be used during the training

- It enables you to identify learners who may need special attention because their learning style contrasts significantly with the methods that you propose to use

- It allows you to put into perspective the learners’ observations and comments about the training content and approach.

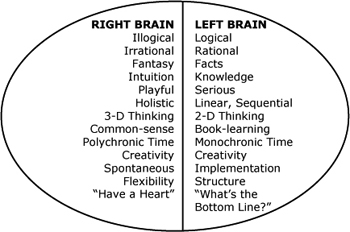

Left-Brain/Right-Brain – Brain Dominance Theory

A fourth perspective on learning styles comes from left-brain/right-brain theory or Brain Dominance Theory, which argues that right-brained and left-brained people think and acquire information in different ways.

Other versions of the theory split the brain into four quadrants:

- The upper quadrant A typifies cerebral processing

- The lower left B quadrant is structured and organised

- The lower right C quadrant is emotional, feeling and concerned with interpersonal orientation

- The upper right D quadrant is concerned with imaginative qualities.

FIGURE 3.5: LEFT BRAIN / RIGHT BRAIN THINKING

We know from research that how a person learns is highly dependent on the way they receive and apply information. People perceive and learn through different systems tied to their basic senses and learning can be described as a “filtration” system, directly related to a person’s senses. Due to this, communication and learning are linked closely together. The average person has one primary system as their method of learning but can use a blend of systems.

This theory identifies three categories of learning styles:

- Visual: People who are “visual”, learn best by seeing or watching how something is done. The written word is their favourite communication process. Examples of how these type of people learn best are through graphics, process flows, checklists, video and demonstration. Example: “I see what you mean”

- Auditory: People who are “auditory” learners prefer to hear how something is done. Trainers need to talk them through skills, discuss them and use verbal instructions. Examples of what works best for learners with this communication style are lectures, being coached verbally through a process, meetings and audiotapes. Example: “I hear what you mean”

- Kinaesthetic: This style of learning describes people who communicate primarily with their senses of touch and emotions. They learn by doing things in a “hands on” environment, by either physically touching something, “getting into it” or “getting a feel for it”. Kinaesthetic learners deal with their feelings about a subject in order to learn. When they feel comfortable with a subject, they retain the information better. Example: “I think I have a feel for that now”.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ADULT LEARNER

As well as understanding learning styles, when you design training activities, it is important that you have in your possession some other pieces of information about your potential learners. Research tells us that you should know something about four individual differences: age, intelligence and ability, emotional state and learning maturity.

Age

There are a number of important differences between young and adult learners. Generally speaking, adult learners learn more slowly and may have more difficulty “grasping” new material than younger learners. Furthermore, if the adult makes a mistake early in training, then the error is likely to persist and correcting it becomes more difficult. You can employ a number of strategies to manage group training or 1:1 training sessions to compensate for some of the difficulties that adult learners experience. You should:

- Avoid, where possible, instruction that relies on the need for memorising large amounts of information. This is a very ineffective strategy to use

- Ensure that the learner has had a chance to demonstrate that one task has been mastered before moving on to the next

- Make sure that errors are corrected as soon as possible because they tend to persist with the adult learner; ideally, you should try to ensure that errors do not occur at all

- Where possible, you should try to instruct the task in meaningful “whole” parts rather than smaller stages that do not seem connected to each other

- Provide variety by changing or modifying your methods of instruction; repetition of the same method can tire adult learners, who like variety

- Longer uninterrupted learning periods are appropriate for adult learners, whereas they are not as effective with younger learners. On the other hand, interrupted or short sessions may cause forgetfulness in the adult learner

- Let the adult learner proceed at his/her own pace and let them compete against themselves rather than against targets achieved by others in the training session

- The “discovery” method can be useful, provided that the tasks are carefully graded into tasks of different levels of difficulty

- With complex tasks, get the adult learner to learn in stages that gradually increase in complexity or difficulty

- Avoid formal time limits for the completion of different phases of the task and do not use formal tests of progress to assess achievement. This is counter-productive

- If a task has to be learned in parts because of its complexity or breadth, use the cumulative parts method – a, a+b, a+b+c, etc.

Levels of Intelligence and Ability

You should not assume that there is a standard or “clone-like” adult learner. Research tells us that there will be greater disparity in intelligence and intellectual ability amongst adult learners than younger learners. Therefore, some of the suggestions we make may need to be modified. You should customise your approach to suit the profile of your learning group.

The learning principles and tactics that you employ should be modified, depending on the ability or intelligence level of the learner. Higher-ability learners are more likely to be able to work from general principles to concrete situations and, depending on the complexity of the task, to cope with learning a task as a whole, rather than breaking it into parts. It may be more appropriate to teach the principle and theoretical aspects to learners with more academic experience before demonstrating and practising. In the case of learners with less academic experience, it may be better to tackle the practical aspects first, before dealing with the theory.

For learners who have less effective learning abilities:

- Use small learning steps and employ the cumulative part method that we explain later

- Proceed from concrete examples to general principles;

- Avoid unstructured learning situations, because lower ability learners are more easily distracted by irrelevant information

- Keep explanations brief, because the learner may have difficulty understanding long, expansive instruction

- Employ short learning sessions that will prevent possible boredom and discouragement

- Make sure that there are plenty of opportunities for practice.

The modern view on intelligence is that learners have multiple intelligences. Howard Gardner has carried out extensive research on the concept of intelligence and has exploded the theory that we are born with an intelligence that is immutable and can be definitively measured. Gardner defined intelligence as “an ability to solve a problem, or make a product that is valuable in at least one culture or community”. He went on to say that “an IQ test won’t show you whether you can cook a dinner, or conduct a meeting”. Gardner identified a number of different intelligences:

- Bodily-Kinaesthetic: Such people enjoy touching, feeling and tapping (surgeons)

- Interpersonal: Good personal knowledge of one’s strengths and weaknesses, “without good self-knowledge, people make mistakes in their personal lives” (Gardner)

- Intrapersonal: People with high levels of intrapersonal intelligence are good at understanding other people and what motivates them. Nowadays, employers prize this intelligence. People who have high levels of this intelligence also have self-knowledge and understand their own feelings, strengths and weaknesses

- Logical-Mathematical: Associated with deductive reasoning, patterns, abstract symbols and geometric shapes (statisticians)

- Musical-Rhythmic: Having a musical ear being able to carry a tune and having a sense of rhythm (musicians)

- Naturalist: Enjoys the outdoors and feels stifled by confined places. They enjoy learning from nature and have a natural affinity with animals and plants (gardeners, botanists, zoologists).

- Verbal-Linguistic: High verbal communication intelligence in both spoken and written language (teachers and broadcasters)

- Visual-Spatial: Involves the ability to think in pictures (artists, architects or navigators, hairdressers)

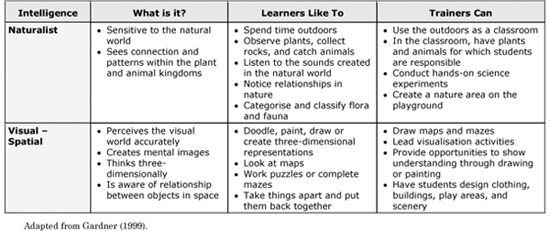

You should be aware of the varied potential and intelligence of your learning group. You can use this information to shape the learning process. Figure 3.6 presents the eight intelligences and explains what the learner and trainer can do in the case of each one.

FIGURE 3.6: MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES & LEARNING

Physical Readiness

The learner’s physical readiness is an important consideration, especially for certain types of training situations. The training situation may demand certain requirements such as physical fitness, visual acuity, hearing, etc.

Emotional State of Learner

A learner’s emotional state may influence how and what is learned. Anxiety, fear or failure and lack of confidence are the sorts of feelings experienced by some learners that can negatively impact motivation and willingness to learn.

You can use a number of strategies to deal with the emotional characteristics of the learner:

- Allow the learner to control the pace of the session. Nudge them forward in a gentle manner – for example, “Do you feel confident now to move on to the next step?”

- Structure the session tightly and avoid the discovery method

- Set more easily attainable goals and do not make comparisons between the learner and other learners

- Give plenty of guidance and emotional support and continuous or frequent feedback on progress. This will bolster the learner’s motivation and self-confidence

- Reassure the learner when there are periods of little or no progress, which are fairly natural in learning situations

- Divide up the instruction into short, easily managed stages

- Ensure that the learner is not left to practise for long periods on their own because, if they get into difficulty, they will need to be given assistance quite promptly.

The attitudes and enthusiasm of the trainer are important influences on how well the learner learns a particular skill. However, trainers must guard against being over-exuberant. “Hyping up”, or stimulating high motivation before and during training, may create anxiety and apprehension in some learners. This is particularly the case if the trainer, at the same time, minimises and is unrealistic about the difficulties of learning complex tasks. These emotions may be felt by the learners because of doubts and fears aroused by the memory of previous failures in their earlier experiences of educational or occupational learning environments. Your sensitivity, style and approach throughout the training event, but especially in the early stages, can help in eliminating, or at least lessening, the emotional blockages and barriers that might interfere with subsequent learning.

Learners who are over-confident or arrogant may need to be managed in a way that challenges and utilises their capabilities – for example, give them an opportunity to lead the session or give a presentation on their views to the group, followed by a Q&A session.

Learner Maturity

Another individual difference that you should take into account is the “maturity of the learner”. Maturity in a training context is not referring to the learner’s chronological age, but rather the learner’s:

- Capacity to set high, but attainable, learning goals

- Willingness and ability to take responsibility for learning

- Education and previous experiences.

If you have a relatively immature group of learners, you should try to ensure that they “walk before they run”. If you push learners too fast, it is likely to have a negative impact on learning time and their motivation. With such learners, you may need to be persuasive, be in control and be more direct. As the learner matures, you can then become less structured in your approach and concentrate on guiding, advising and supporting. A mature learner will respond more effectively to a participative, challenging and collaborative learning situation.

MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT ADULT LEARNING

Many misconceptions exist about learning and the adult learning process, in particular the following.

Learners over a Certain Age Cannot Learn

This is a common misconception. There is little evidence to support such a myth; anyone at any age can learn. It may, however, take longer for an older learner to learn, because their rate of learning and retention may become slower with age. But, if an individual wants to learn, then he/she can.

It is the learner’s personal approach to life that influences learning. The major positive factor that adults bring to learning is their motivation: they already have an idea of the relevance of what they learn. This is something younger learners sometimes lack. Adults have the capacity to learn a vast number of new skills and apply them effectively to a range of situations. Information may be absorbed at a slower rate and is therefore less likely to evaporate.

Technophobia

Many organisations that have experienced staff shortages have recruited more mature employees. This more mature employee may not have been exposed to new technology prior to this experience and can suffer from a fear or a block to using it. This creates problems for trainers whose task may be to run induction training or teach basic technological skills. Training strategies can be employed effectively to overcome technophobia. The core issues are creating a safe environment where learners can discuss their lack of confidence. Reassurance from the trainer is vital.

The Person who Learns Fast is Best Suited to the Job

In some ways, this statement could be accurate, in so far as some learners experience a high level of achievement if they are continually learning new things, rather than coping with routine work, which is relatively easy to learn.

It is important to get the balance between the different aspects of a job, which the learner can master with time, and the more mundane work, which is done routinely. If there is an imbalance, the person who learns quickly and is seeking new or more difficult tasks will become demotivated because their interest in the learning process is not sustained. This is one of the essential reasons why you should know the ability level of your learners.

It is important to recognise that learners will not be motivated, if they are considered to be less effective learners and labelled as such. Learners at all levels must be encouraged. Less effective learners are more suited to routine tasks of a less complex nature. It should be noted too that there are learners who learn some of the more routine tasks very fast, but soon become very bored if there is nothing new to learn. A trainer needs to use some tricks here – they can get the fast learner to work with the other learners as a coach or guide, or give the fast learner more complicated problems to work on and to present their findings to the group.

There is a Strong Correlation between Academic Success and Performance on the Job

It is not correct that only high academic achievers will succeed. On the contrary, an individual may have a long list of academic qualifications but possess very little business acumen or practical intelligence. It is not possible to specify that a degree, in whatever subject, will ensure that the person becomes an entrepreneur. However, possession of a degree does suggest that a person will have a level of analytical skill that will help in a position when a situation needs to be analysed, the problem identified and problem-solving skills applied, as most degrees include this essential element.

It is necessary, however, to consider the late developer – not only those in the early to late teens, but also the older developer, those who did not recognise their own abilities until quite late in their lives. There are also those learners who did not have the opportunity, for a whole host of reasons, to study for a formal qualification. This type of learner can be very successful in the workplace

People Learn all they Need to Know on the Job

This is generally not a correct statement. It is true that employees do learn on the job; indeed, they are continually learning on the job every day – for example, by exploring and experimenting how a task can be done more efficiently or more effectively to save time, energy or cost. Through experimenting, the learner can learn to do the job in many different ways.

Learning is a continual process, but it would be most undesirable for an employee to attempt to perform a job on a production line for example, without first acquiring the basic knowledge and skills needed. A good example of this misconception relates to management and supervisory skills. The fundamental skills of management are often overlooked or regarded as capable of being learnt on-the-job. The preferred approach is that potential supervisors or managers should learn the essential skills and acquire the knowledge needed for these positions, through structured learning activities.

People Learn Nothing from Mistakes

Some learners do not learn from their mistakes, as they hold the misguided attitudes that “… oh well, everyone makes mistakes” and that mistakes are best forgotten. This negative reaction will not lead to performance standards being achieved and is sometimes indicative of learners who perceive themselves to be inferior or incapable in some way. This attitude may be a result of a previous mistake that was poorly handled by a trainer or manager. A trainer or manager should be supportive and encourage an employee by coaching or counselling where appropriate. Some learners make mistakes merely because they lack self-confidence, rather than because of any lack of ability. Encouragement is imperative, if employees are to learn from the mistakes they make. A mistake needs to be regarded positively as a learning opportunity.

It is natural that employees will make mistakes from time to time, but those employees who view it as an opportunity for learning and self-development will become valuable employees. Employees should be encouraged to communicate their experiences of mistakes, as others may make the same mistakes. This is particularly important where there is a health and safety aspect that requires corrective action.

People Learn All They Need to Know at the Beginning of their Careers

Internal and external environments are constantly changing; many organisations now view the culture of their organisation as a “change culture”. As a result, many employees have at least one career change. The reasons are varied, but one is that many individuals perceive a change as a career development strategy. Thus it is not true that one learns everything one needs to know at the beginning of a career.

Telling and Exhortation by an Instructor is the same as Learning by Listening

This is false because fatigue leads to lack of interest and boredom, irrespective of the topic. However, there are a few exceptions, such as an outdoor activity to develop individuals in decision-making and personal effectiveness, including team-building. The activity itself increases and retains the level of interest of the learner. The feedback discussions are generally lively and highly participative, indicating the level of response to the activities, and reinforcing what has been learnt.

Effective instruction consists of question and answer sessions, demonstrations that are seen clearly, and accompanying supporting material. Learners should be constantly stimulated to retain their interest. This is not an exclusive list, but emphasises the importance of varied learning methods to heighten retention by learners.

Consideration of the length of periods of instruction is fundamental to the success of a learning event. Appropriate breaks of relevant durations are essential and should be designed into the programme schedule. It is a good idea to build in shorter breaks of approximately five minutes every hour. Adults are not used to sitting in one place for long periods in a learning context.

Psychologists consider that it is impossible for learners to retain everything they are taught, and generally agree that retention is approximately 25% of what is learnt initially; the reinforcement of learning is therefore extremely important.

UNDERSTANDING CONDITIONS OF LEARNING

We made a brief reference to the laws of learning earlier in this chapter; here, we go into more detail. We will address the practical implications of these well-established principles when we consider training design and delivery.

Sequencing the Training Material

Training content should follow some logical order that makes sense to the learner. If this is achieved, it will make learning, as well as subsequent recall and application, much easier.

There are a number of “laws” that will help you to arrange material in the best order:

- Proceed from the easy or simple to the difficult or complex: This represents a fundamental principle. In some tasks, learners must acquire basic knowledge or skill before progressing to more complex material or situations. Moving to the latter too quickly, before the fundamentals are in place, will result in learning gaps

- Proceed from what the learner knows to new or unknown material: The trainer/instructor must try to build on what the learner already knows or can already do. Forging a link between the known and the unknown will usually make new learning much easier, not just because learners may feel less anxious handling or dealing with new material, but because they start from a pre-established base of knowledge

- Proceed from the practical or concrete to the more abstract and theoretical: Learners will eventually learn general principles or rules if, initially, those principles or rules have been demonstrated or illustrated by way of concrete example. Asking them to acquire abstract principles in isolation, without first clearly showing the specific and relevant situations to which the principles apply, will hinder the build-up of their knowledge and understanding.

Whole versus Part Learning

Another important consideration is whether or not to cover what has to be learned in one complete session, or whether to break it up into smaller sessions. For instance, if the skill to be learned is made up of several elements, should it be learned all at once or should the learner be taught the elements separately, before combining them into the whole? The answer to this question seems to be “it depends”.

The “whole” method is more advantageous than the “part” method when:

- The learner is intelligent (making a very able person learn a series of easy parts may have an adverse effect on motivation)

- The learning of, and practice on, the task or skill is spread out over time rather than massed into a short time frame

- The task or skill is not particularly complex and the elements that make it up seem to “fit” together naturally.

Setting Objectives and Sub-Objectives

In order to stimulate and sustain a learner’s motivation, you should outline the learning objectives to be achieved at the beginning of the programme. This will give the learner a clear idea of what has to be accomplished as a result of the one-to-one training or coaching experience. Furthermore, it will allow learners to judge their own performance against the objectives set.

If objectives are to be valuable in a learning context, the following conditions must be met:

- Objectives must be within the learner’s ability to achieve them

- Feedback on how well the objective is being met must be given to the learner at appropriate intervals

- Learners are given specific challenging objectives rather than modest objectives or no objectives at all, or simply encouraged to “do your best”.

Apart from telling the learner about the overall learning objectives at the outset, you can influence the learner’s ongoing attitudes and motivation towards the learning programme by setting or agreeing a series of shorter term or interim objectives with him/her. Having progressive learning objectives will allow you to monitor the learner’s achievement more closely and also, to a certain extent, to alert the organisation to workplace activities required to reinforce the learning following the training.

This link is vital to consolidate learning. Training is not a stand-alone activity. Learning can evaporate, if the trainee is not given the opportunity to use the skills in the workplace – for example, a presentation skills course needs to build in on-the-job opportunities to complete at least four presentations in the workplace soon after the course is completed. Coaches need to be identified to give structured feedback to the trainee so that they can develop their skills to a high level on-the-job.

Providing a Meaningful Context for Learning

Apart from stimulating the learner’s motivation by setting learning objectives, you need to structure the learning environment in a way that maintains alertness throughout the training sessions. Sessions that are run as on-the-job training sessions are already placed in the context of the work environment and little can be done to make the learning more stimulating. However, some aspects of training may have to be taught as separate items and may not be directly related to what has gone before or what follows. Giving an overview of the task and showing its relationship to other tasks and activities provides a more meaningful context in which the learning can take place. Another way in which a meaningful context can be provided is by simulating an environment that resembles, as closely as possible, the real working conditions – for example, using models of the workplace.

Directing Attention

There will be occasions when you have to draw the learner’s attention to particular elements of the material to be learned. These features may be associated with any of the six senses: Vision, Hearing, Touch, Smell, Taste, and the Proprioceptive sense (this sense relates to the position and movement of the body – for example, balance).

Guidance, Prompting and Cueing

These terms are very similar in that they are all used to direct learners at times when they are physically involved in doing something and you feel that there is a need to provide some help. Although they are explained separately for reasons of clarity, their function is the same.

Guidance

Guidance can be given in two ways:

- It can be a form of demonstration in which you show the learner the “right way to do something”, such as how to hold a tool properly before they actually use it.

- It can be used when mistakes can occur and the learner is alerted to the need to take care or to work more slowly.

It is particularly important to provide guidance in the early phase of the learning of complex tasks. Errors that are made at this time are likely to be repeated and subsequently, learning resources will have to be devoted to unlearning those early mistakes. It is also important to prevent errors occurring in training where serious safety problems or damage to equipment might result.

However, there are circumstances in which allowing errors to be committed might be more beneficial to learning, than making correct responses. This needs to be monitored carefully.

You will need to consider the amount of guidance you provide. Observing a learner’s reaction to guidance will give some indication of how much is welcomed and needed and how far the trainer can go before there is a danger of boredom and demotivation. The learner may perceive that he/she does not have sufficient independence and control over the learning situation, if the trainer is too controlling and thus he/she may not learn as effectively as possible.

Prompting

Prompting as a skill is most applicable to learning verbal material and not to procedural tasks. After some initial learning of information, the learner may be required to recall it and is helped accomplish this task by being “prompted” by the trainer. Skilful questioning of the learner may also act as a form of prompting, leading to the correct response or action. As with guidance, prompting appears to be particularly effective in the initial phase of the learning process. We will say more about it in Chapter Eight.

Cues

You can speed up the learning process by providing or highlighting easily identifiable and easily remembered cues that trigger the correct response or sequence of actions. For example, in some forms of social skills training such as selling, you can direct the learner’s attention towards cues such as a customer’s facial or oral expressions, tone of voice, etc. This will help the learner to interpret particular social situations and helps them to behave appropriately.

Practice and Rehearsal

It is the learner who learns. Therefore it is necessary to ensure the learner’s participation and active involvement if learning is to be effective. Practice and rehearsal are two of the most important activities that learners must engage in, under your influence and direction, in order to acquire new knowledge and skills.

There are two initial conditions that you should be aware of, if “practice is going to make perfect”:

- The learner must be motivated to improve performance

- You must provide feedback on an on-going basis, both during and at the end of the practice session.

Similarly, for rehearsal to be an effective method of ensuring that verbal or procedural material is remembered, you must involve the learner in active retrieval and recall of the material, during the training or coaching session. This form of activity is important because:

- It requires active participation by the learner, which helps to maintain attention and interest

- Active recall gives the learner an opportunity to practise the material

- Giving constructive feedback about accuracy will indicate to the learner what he/she does or does not know and should also help them to direct and allocate subsequent effort and time to perfecting the knowledge/skill.

Distribution of Practice

You will need to consider whether practice should be completed all at once (massed) or spread over several sessions (distributed). It is difficult to provide conclusive guidelines, although the following should be considered:

- Distributed Practice: In learning manual skills, distributed practice is usually more effective than massed practice, both in terms of the phases of learning and of retention of learning

- Series of Sessions: When the material to be learned does not make immediate sense to learners, or cannot be associated with what they already know or are skilled in, it will be more difficult to learn in a single session as opposed to a series of sessions

- Timing is Crucial: The ideal time interval between practice sessions and the timing of the session itself will depend on the nature of the task to be learned and on the learner’s personality, previous experience, etc. If the interval is too long, then forgetfulness may become a problem and a relearning or a “warm-up” period may be necessary. On the other hand, if the interval is too short, then learners may become bored or suffer from mental or physical fatigue.

Feedback, Knowledge of Results and Reinforcement

Learners need to know how well they are doing at all stages in the learning process. This will ensure that they learn effectively and improve performance. Feedback may focus on how well a learner performs a particular task. Alternatively, you can direct the learner to look out for cues and information that allows the learner themselves to judge how effectively the learning is progressing.

You should be concerned with two important features of feedback:

- How much to give

- How specific to make it.

We know from research that too much specific feedback in the early stages may not necessarily lead to improvements in performance. If you overload the learner with too much detailed information about performance, it may only serve to confuse and may also have a depressing effect on their motivation.

The general recommendation on feedback seems to be to give the learner a small amount early on, increase the amount and specific detail as the learner improves, withdraw it gradually as the skills to be learned become more established, and finally exclude it altogether.

When giving feedback, you should not ignore your learner’s emotional needs. Some form of emotional reward – for example, saying “well done” – should follow effective performance of parts, or the whole, of the task. However, the learner should not become overly dependent on your emotional support as their confidence and performance may be adversely affected when support is withdrawn. On the other hand, praise or reassurance is necessary and important when progress is slow or non-existent and the learner needs to be motivated to achieve a higher level of performance.

Retention and Forgetfulness

Forgetting what was originally learned is a common enough experience. It is important to ensure that skills and knowledge learned in training situations are retained and transferred to the work context. This may be difficult to achieve if there is little or no opportunity to use the knowledge and skills immediately or on a relatively frequent basis in the work context. You can employ a number of strategies in the training context that can facilitate retention and prevent or minimise forgetfulness:

- Introduce a job aid – any form of printed document containing verbal or pictorial material kept in the place of work that can be used as a memory-jogger or as a procedural guide for a difficult, complex or infrequently performed tasks

- Use distributed, rather than massed, practice sessions

- Train to produce over-learning in the learner – train to a level of performance above that strictly needed to achieve the training objectives

- Introduce further supplementary practice sessions after the learner has achieved the required level of mastery

- Encourage the learners to engage in mental practice or rehearsal when they return to their work locations

- Make the training as meaningful as possible by linking it with the learners’ previous knowledge and experience and by organising and sequencing it to make initial learning easier

- Ensure that the way the training and coaching sessions are run motivates the learners stimulates their interest and is not an experience they would rather forget

- Ensure that the learner is an active participant in the session rather than merely a passive recipient of the material.

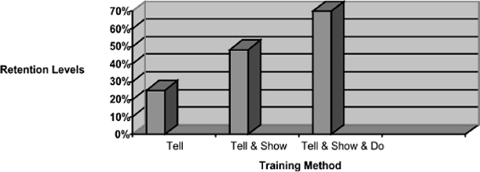

Retention of learning is facilitated when the learner is allowed to watch and perform a task in addition to being told how to perform it. Incorporating hands-on training into a lesson plan significantly improves learners’ learning retention.

Figure 3.7 shows retention percentages after 60 days for three types of training.

FIGURE 3.7: LEARNING RETENTION LEVELS FOR DIFFERENT INSTRUCTIONAL APPROACHES

Criticism and Punishment in Training

We know from research that constructive criticism has both advantages and disadvantages in a learning context. You should be concerned that criticism does not destroy employees’ confidence or self-esteem. The way in which you communicate criticism is important.

If learners have been previously continuously criticised in the workplace, it may take a long time, extreme patience and understanding to re-establish the self-value of those individuals before any forward steps can be assumed or indeed measured in any way. The re-building of a learner’s self-esteem is a lengthy process and as a trainer you need to be patient.

We believe that punishment and fear of any kind are not conducive to the learning process. Research indicates that these activities inhibit individualism, stifle creativity, induce a sense of failure and produce neuroses, all of which deprive learners of their dignity.

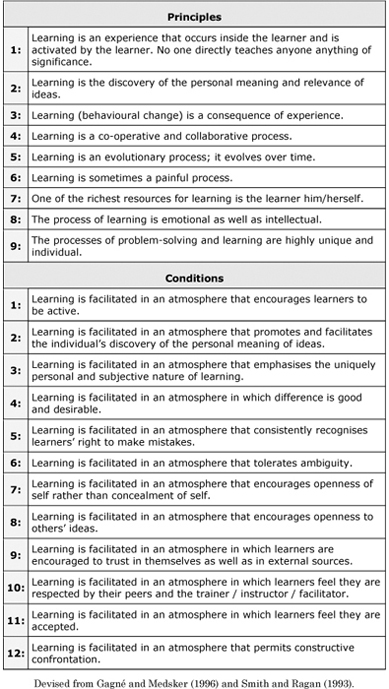

FIGURE 3.8: PRINCIPLES AND CONDITIONS OF LEARNING

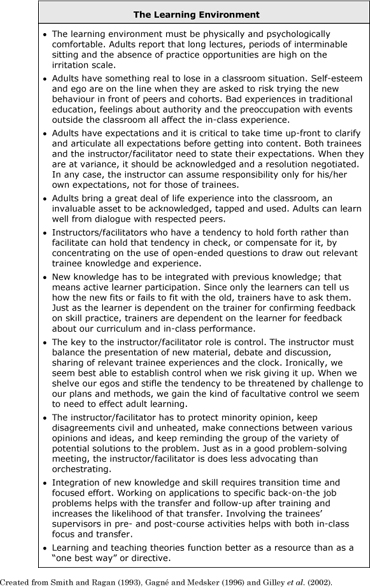

The Learning Environment

There is a strong body of research evidence indicating that effective learning will be transferred to the workplace, if it takes place in an environment that is conducive to learning. The comfort and relaxation of learners can help learning. The external environment may also be significant. If, for example, day release or evening classes have to take place several miles away from a trainee’s work or home, this is not likely to enhance the motivation to learn.

Some of the issues that you need to consider in this respect are:

- Every learner has worth as a person. An individual is entitled to maintain his self-respect and dignity. The learner’s feelings are important and should be respected. Critiquing learner behaviour is differentiated from rejecting him/her as a person

- Human beings have a capacity to learn and grow. Generally, people do what they have learned to do and usually follow the habits that have guided them in the past. Thus, they tend to be consistent in their actions. However, they also change their attitudes and beliefs and develop new ways of doing things as a result of new emotional-intellectual experiences

- The most effective type of learning – that which is most likely to influence attitudes and behaviour – comes through having emotionally-involving experiences and reflecting upon them. Individuals learn as they are stimulated and challenged to learn. They develop ways of behaving as they get responses (feedback) from other persons about, or to, their behaviour

- A permissive atmosphere – a group climate conducive to free discussion and experimentation with different ways of behaving – is a necessary condition for learning. Only when an individual feels safe enough to behave normally is it possible to detect the behaviours that are unproductive – those that are not effective with other persons. In a non-judgemental atmosphere, a trainee is more likely to be receptive to feedback from others and willing to try different ways of expressing her/himself

- The training role carries responsibility for helping the learner learn from their experiences. This involves facilitating the development of conditions within the group that will be conducive to learning and guiding the learning experience. It implies that the trainer, as a person, influences events within the group and that his/her behaviour is also a legitimate subject for examination. In fact, the trainer’s willingness to encourage scrutiny of their own role behaviour is a crucial factor in furthering the growth of a climate that permits examination of the role behaviour of members of the group

- The most productive way to work is to share the diagnosis of problems and, collaboratively, to plan and evaluate activities. This approach leads to greater emotional involvement on the part of participants. It results in greater member commitment to decisions

- The study of group process – how work is done and the characteristics of the interaction among persons as they work – helps to improve group efficiency and productivity. The crucial factors that interfere with co-operative effort more often lie in the manner in which people work together than in the mastery of technical skills. Problems of involvement, co-operative effort, relationships between individuals, and of relations between individuals and the group are all of universal nature. The best place to study such problems is in the immediate present. Hence, examination of what is going on in the group, the here-and-now, provides the richest material for learning. Every member can participate meaningfully in the examination because they have witnessed and experienced the data being discussed.

Intellectual Readiness

Learners bring something with them to any new learning situation. This will include previous experience, a level of existing knowledge, specific skills, special aptitudes, general potential and capacity of learning, etc. This will have an influence on how ready learners are to undertake the training that is being planned for them.

In some cases, it may be necessary to introduce basic or remedial training before proper training can begin. In other cases, it may be possible to speed up the training, or even omit some of it, if learners have already mastered some of the skills or have sufficient knowledge.

Motivational Readiness

One of the strongest findings from the research is that learning is negatively affected if the learner has no desire or is not motivated to learn. Most positively, it can be a rewarding experience for both the learner and the trainer when the level of motivation to learn is high.

There are a number of factors that potentially might influence trainee’s motivation. These include meeting their needs, rewards and incentives, the perceptions, expectations and attitudes that they hold.

There are four categories of needs that can be met in a training situation:

- Safety Needs: These needs relate to the security that can be achieved through training. This is when the learners know that they can undertake potentially dangerous tasks safely and without danger to themselves

- Emotional Needs: These needs are satisfied when trainees are able to see that learning new skills and acquiring additional knowledge will affect their performance by giving them more control and independence in what they do and by giving them a feeling of achievement, self-confidence, autonomy, approval, acceptance and recognition in the eyes of other workers, and a feeling of belonging

- Intellectual Needs: Being able to master new skills and new knowledge is stimulating for many trainees. They need variety in what they do and the opportunity to exercise curiosity in finding out about the what, why and how of the learning that they are undertaking

- Self-fulfilment Needs: Most people like to feel that they have “got somewhere” and in this respect training or learning helps to provide a meaning and sense of purpose.

Which of the above needs are important for any particular learner will depend on their personality, background and experience.

Broadly speaking, there are two main forms of reward or incentive that are linked with learning events. There are those that are closely associated with the task itself, called “intrinsic”, and those that are more in the way of being an outcome of performing the task, called “extrinsic” outcomes:

- Intrinsic Rewards come from the satisfaction that derives from being able to perform the job properly – for example, preparing a column of figures that balance, receiving the thanks of satisfied customers, building a house, etc, are all activities that provide intrinsic rewards

- Extrinsic Rewards are independent of the task and include such rewards as money, promotion, enhancement career prospects, receiving a certificate. Therefore, the task itself could be boring and not intrinsically rewarding but the incentives that go with it provide the motivation.

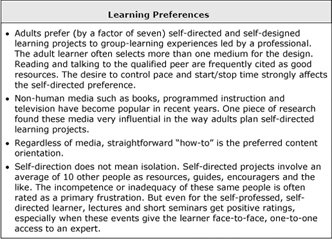

We conclude this chapter with an outline in Figure 3.9 of the main findings that research indicates will help you design high quality T&D activities.

FIGURE 3.9: SUMMARISING WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT THE ADULT LEARNING PROCESS

BEST PRACTICE INDICATORS

Some of the best practice issues that you should consider related to the contents of this chapter are:

- Learning is an active process and adults prefer to participate actively. Therefore, those techniques that make provision for active participation will achieve faster learning than those that do not

- Learning is goal-directed and adults are trying to achieve a goal or satisfy a need. Therefore, the clearer, the more realistic and relevant the statement of the desired outcomes, the more learning that will take place

- Group learning, insofar as it creates a learning atmosphere of mutual support, may be more effective than individual learning. Therefore, those techniques based on group participation are often more effective than those that handle individuals as isolated units

- Learning that is applied immediately is retained longer and is more subject to immediate use than that which is not. Therefore, techniques must be employed that encourage the immediate application of any material in a practical way

- Learning must be reinforced. Therefore, techniques must be used that ensure prompt, reinforcing feedback

- Learning new material is facilitated when it is related to what is already known. Therefore, the techniques used should help the adult establish this relationship and the integration of material

- The existence of periodic plateaus in the rate of learning requires frequent changes in the nature of the learning task to insure continuous progress. Therefore, techniques should be changed frequently in any given session

- Learning is facilitated when the learner is aware of progress. Therefore, techniques should be used that provide opportunities for self-appraisal. Learning is facilitated when there is logic to the subject matter and the logic makes sense in relation to the learner’s repertoire of experience. Therefore, learning must be organised for sequence and cumulative effects.