10: THE MANAGER AS TRAINER & DEVELOPER

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the contribution that the manager can make to training and developing staff in organisations

- Explain the positive and negative features of developmental relationships

- Explain the different training and development roles that the manager may perform in an organisation

- Explain the different types of coaching activities that a manager performs

- Explain the skills and strategies that the manager can use to mentor employees

- Explain the steps that can be taken by the manager to use performance reviews for development purposes

- Explain the characteristics of coaching and how to use it in a corrective and developmental context

- Explain the value of counselling in a developmental context

- Outline the value of a personal development plan and explain its key components.

INTRODUCTION

We have considered the roles and skills of the trainer in facilitating training and development in organisations. We have identified and described at various points the role of the manager in developing employees. We give more consideration to the roles of the manager as a trainer and developer of staff in this chapter.

We consider the manager to be an important stakeholder in influencing and determining the effectiveness of T&D in an organisation. Typically, managers perform a number of important T&D roles. They may carry out on-the-job training, they may be involved in both corrective and developmental coaching, they may act as formal and informal mentors and they may undertake developmental reviews.

We consider the personal development plan to be an important component of effective development. We explain the issues you should consider when constructing a personal development plan. We consider each of these development dimensions in this chapter.

DEVELOPMENTAL RELATIONSHIPS & THE MANAGER

The process of training and developing staff in organisations does not take place in a vacuum but occurs as a response to the environment in which an individual works. The manager is a major component of the learning environment. Managers influence the nature and direction of an individual’s development, and also have responsibility for the learning and development climate. We firmly believe that individuals are responsible for their own learning, although the manager has a major role to play.

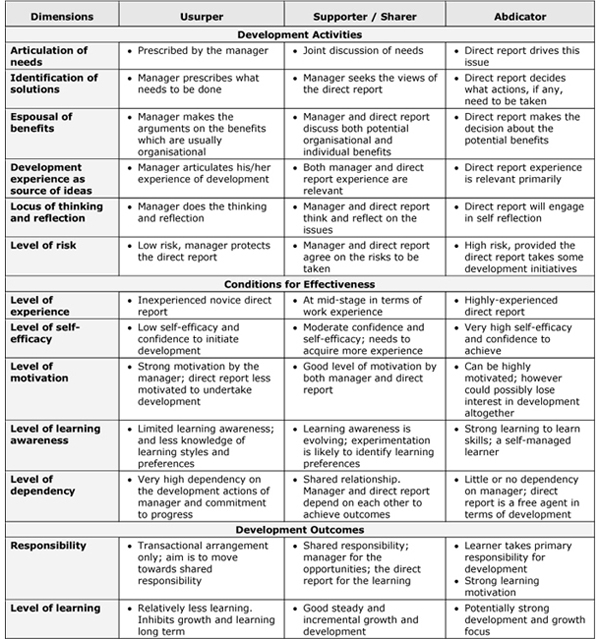

There are three distinct developmental relationships that a manager can adopt in respect of developing his/her direct reports

- The Usurper: In this relationship, the manager seeks to take over fully the responsibility for a direct report’s development. This is a role that may be appropriate for the manager to play at the initial stage of a direct report’s development. It may also be an appropriate role to perform where the learner has low trainability, less learning maturity and is relatively inexperienced. But this role should be no more than a temporary role for a manager

- The Supporter / Sharer: This relationship is a more positive and constructive one from both the perspective of the manager and the direct report. Both manager and direct report maintain a constructive dialogue on development and both have different development responsibilities. The manager provides the opportunities for development and the direct report has the responsibility for taking and using them. There is a strong sharing of ideas and discussion of development needs. Manager and direct report are likely to discuss development actions and address both organisational and personal needs. The supporter / sharer role is a demanding role for both parties to play. It requires a sharing of ownership, a strong level of motivation by both parties and a level of agreement on the development needs that are to be addressed

- The Abdicator: The third developmental relationship is the abdicator. A very advanced development relationship could evolve from supporter / sharer to abdicator over a period of time. The manager in this case abandons the interface. There are a number of implications that can flow from this withdrawal of responsibility by the manager. If the direct report is mature, then this role offers the potential for the direct report to take increased ownership for development activity. It allows the direct report to self-direct his/her learning and self-manage the process. However, the direct report may ignore the organisational agenda and focus primarily on individual development needs. Where the direct report possesses less maturity and emotional resilience and has not fully developed his/her learning skills, it is likely that limited development may take place. This is a risk that the manager may have to take.

Figure 10.1 provides a summary of the three roles.

FIGURE 10.1: CHARACTERISTICS OF THREE DEVELOPMENT RELATIONSHIPS

Training & Development Roles of Line Managers

- Appraisal of performance

- Appraisal of potential

- Analysis of development needs and goals

- Recognising and facilitating developing opportunities

- Giving learning a priority

- Using everyday activities for learning purposes

- Establishing learning goals

- Accepting risks in subordinate performance

- Monitoring learning achievement

- Providing feedback on performance and learning

- Acting as a model of learning behaviour

- Using learning styles to facilitate meaningful learning

- Offering help, support and counselling

- Direct coaching of employees.

Line managers are “key players” in promoting training and development. One of the fundamental tenets of Human Resource Management is that managers should take responsibility for the “people management” as well as the “task management” aspects of their role. This is in contrast to the situation where responsibility for training and development is “hived off” to development specialists and trainers or is perceived to be the responsibility of training departments. There is a strong rationale for this approach – simply that managers are in day-to-day contact with their employees, they know the job role and are aware of the direct report’s strengths and weaknesses. Therefore, they are ideally placed to take an active role in the development of their direct reports, whose performance they are expected meant to manage.

The problem with this is that managers often tend to be task-driven and do not possess the people management skills necessary to take on a significant developmental role. Nevertheless, many organisations now expect line managers to take a degree of responsibility for employee development, and are putting in place supporting systems to ensure that this happens. Sometimes, 360-degree appraisal is used, and staff development responsibilities are being written into job descriptions and appearing in managers’ performance objectives. In addition, organisations are trying to provide managers with the skills they need to take on these responsibilities.

Typical responses from line managers when faced with the news that they share responsibility for the development of employees under their supervision range from comments like “I’m paid to manage the job, not train people. That’s what we have a training department for!” to “Can you send Joe on an interpersonal skills course? He must learn how to deal with people”.

The question arises as to why line managers are reluctant to become involved in T&D. The research evidence suggests that line managers may not have staff development clearly specified in their job description and performance objectives; that they lack the skills necessary for needs assessment, course selection and evaluation, and they may prefer to defer to centralised training departments where expertise is seen to rest. This system of expertise is often likely to be perpetuated by a centralised training department concerned with justifying its own existence.

Whatever the rationale for resistance, line management involvement is considered critical to the success of T&D. Many of the reasons for this have been articulated already in Chapter Two but, in summary, the increasing pace of organisational change requires that decision-making be taken closer to the work being done. It is line managers who are most continually involved with employees, know their development needs, understand their part of the business better than anyone else, and are in the best position to evaluate the results of employee development activity as it relates to the current and future work of the work group.

Whatever the rationale for resistance, it is easily overcome if top management makes T&D a high priority. Shifting both responsibility and authority, in addition to resources, for T&D to line managers can have significant influence on line manager behaviour. If coupled with appropriate development of the skills needed, this can produce positive outcomes.

There is general agreement as to the dimensions of the line manager’s role for employee development. It involves giving active support to the role of employee development in the organisation. Setting aside time to think about and engage in employee development activities can do this. Short-term workload should not be accepted as an excuse for failure to allow employees to participate in T&D – this merely demonstrates the manager’s lack of ability to plan and manage human resources. Second, managers should engage in regular, formal need assessment activities with their staff. Often the most appropriate forum for this is with the work team; at other times, it is with individual employees. The development and updating of the “personal development plan” should be seen as an opportunity to reinforce the message of continuous development that is inherent in the philosophy of employee development.

This suggests that managers themselves will need new skills: to coach, to assess training and development needs and to evaluate T&D activities that have been conducted, as well as the increased management skills needed to work with a workforce that is continually developing and changing its own skill base. Therefore, they must be active participants in the employee development process.

There is evidence that the optimum developmental relationship requires the espousal and implementation of a number of important values and actions by the manager, including:

- Manager and direct report work with a natural curiosity and the manager is continually concerned about the learner

- Manager and direct report agree some form of explicit or implicit learning contract

- Real issues and problems are worked on and used as vehicles for learning

- Feedback on self-performance is encouraged and practiced

- Learners are considered to have a valuable contribution to make to the process of learning

- Learners are trusted to learn for themselves

- Responsibility for learning is shared with learners

- The manager offers resources to learn

- Learners continually develop and are encouraged to develop

- Learner and manager have joint responsibility and power to make development decisions

- There is a climate of genuine mutual care, concern and understanding

- The focus is on fostering continuous learning, asking questions, and the process of learning, and learning is at the pace of the learner

- The emphasis is on promoting a climate that supports deeper, more impactful learning that affects life behaviour

- There are no teachers, only learners, in the developmental relationship.

MENTORING & COACHING

Mentoring and coaching are two development processes that you will most likely use in a T&D role, either as a trainer or as a manager. We provided a brief definition of these concepts in Chapter One. We explain in more detail the differences between both concepts now.

Coaching is a process in which an individual (usually a manager) interacts with another (direct report) to teach, model, and provide feedback on technical, professional and interpersonal skills and behaviours in a future-focused constructive way. The coach seeks to use everyday experience to improve performance.

Coaching, as a development tool, performs important functions:

- To enable the direct report to recognise their own strengths and weaknesses

- To encourage the direct report to establish targets for future performance improvement

- To monitor and review the direct report’s progress in achieving targets

- To identify any problems that are likely to impact performance and progress

- To assist the direct report in generating alternatives and developing development action plans

- To enhance the direct report’s understanding of the work context

- To assist the direct report to realise their potential.

Mentoring is a process that deliberately pairs a person who is more skilled or experienced with one who is less skilled or experienced (the protégé or mentee) in order to transfer skills and experience in a focused, effective and efficient manner. The skills transferred may be job-specific, technical or professional, generic or career-oriented. The reporting relationship is “off-line” – that is, not between a manager and his/her direct report.

Many trainers consider mentoring to be a career management tool used by organisations to nurture staff. Mentoring generally involves the giving of advice and guidance or in providing a role model. Mentors focus on the development of the learner, giving time and attention beyond the role boundaries of the manager. Development usually takes place “as required” at a pace to suit the individual.

Mentoring processes usually include the following elements:

- Determining which goals, needs and opportunities of the organisation can be supported by increased skills and experience

- Developing strategies for pairing employees in a mentoring relationship on the basis of skill deficits in the employee and the presence of those skills in another

- Securing some form of agreement for each pair that defines the roles, focus and duration of the mentoring relationship.

Mentors typically carry out tasks such as teaching, tutoring, coaching, modelling, serving as a sounding board, demonstrating, listening, reflecting on the contribution of the mentee, giving feedback, counselling and guiding. The role is therefore all-embracing and requires a strong skill set.

Informal mentoring occurs in many organisations. Although it is a positive process in that it enables individuals to form natural pairs, mentors often choose mentees who are very much like themselves and impress their beliefs and styles on the protégé or mentee. It is possible that learners with strong development potential may be left out of these informal relationships.

There is evidence indicating that the creation of an effective mentoring relationship is a function of personality, so some organisations have adopted a facilitated mentoring strategy. This process is an overall structure and series of activities that enable the creation of a mentoring relationship. The process is available to any individual who perceives that he or she has potential for development and is willing and motivated to take more responsibility for personal and management development

Coaching and mentoring processes are appropriate to use in a number of situations:

- Performance Improvements: Coaching is appropriate where performance improvements are needed, when someone starts a new job task or procedure or where someone is initiating a professional development process

- New Organisational Skill Requirements: Mentoring and coaching are useful processes where organisations are concerned about the future skill needs of the organisation, as they can contribute to developing these skills

- Inefficient Formal Training Processes: Typical formal training courses are aimed at the average learner. It is common on many formal courses to find that participants have widely varying skills and knowledge and so a significant proportion of training content may not be relevant to a participant. In a coaching or mentoring situation, the learning is precisely targeted to the learner’s specific needs. When this specific focus is clearly defined, they are very effective for learning

- Speed of Traditional Formal Learning may be too Slow: Formal learning events may not be scheduled at a time to suit the demands of the organisation for new skills. Training departments may only provide courses at a particular time. Coaching or mentoring strategies may be appropriate to address issues in the short-term and to meet skill requirements in a timely fashion.

Figure 10.2 shows the main differences between coaching and mentoring.

FIGURE 10.2: DIFFERENCES BETWEEN COACHING & MENTORING

The Manager as Coach

Coaching involves helping another person systematically and deliberately to develop skill and knowledge. It usually involves personal development in terms of attitudes and motivation. Some commentators argue that the role of coach is an amalgam of four other roles that are usually performed by a manager:

- Appraiser: This role focuses on what development is required, what the performance standards are and the preparation of a development plan to achieve them

- Supporter: This role is concerned with creating opportunities, providing support, services and recourses and counselling and helping the direct report with problems

- Communicator: This role is concerned with giving balanced and constructive feedback. The coach offers advice and suggestions, develops positive relationships and is an information source

- Motivator: This role focuses on encouraging, giving recognition, challenging, articulating expectations and understanding the needs of the direct report or developer.

Figure 10.3 presents a summary of key dimensions of the coach in a training and developmental context. These represent the more commonly-emphasised roles.

FIGURE 10.3: DIMENSIONS OF COACHING IN A T&D CONTEXT

- Experiential Coaching: This takes place when the coach is observing or sharing the individual’s on-the-job activity. The coach can guide the work performance encourage, give feedback and “model” the appropriate skill

- Reflective Coaching: The coach asks questions about the individual’s performance in the development area so that the key aspects of the experience can be recalled and thought about. This may produce new angles and insights for the person being coached. It can often produce significant leaps forward in learning

- Guideline Coaching: This approach involves the coach in explanation or in giving rules and guidelines. It is the instruction element of coaching

- Trial Coaching: The coach gives the individual the chance to try out a new skill. Both parties manage the degree of risk in the trial. It is an opportunity to test and experience in relative safety, as a preparation for the real thing

- Coaching as Preparation for Learning: If the individual is to have a development opportunity in the near future, the coach can help maximise the learning by discussing it beforehand. If the person is able to attend a course, for example, the coach manager should spend time checking what learning they both would like to occur on the course. It will help the learning motivation of the learner to share hopes, enthusiasm and expectations.

- Coaching as Learning Reinforcement: New learning needs reinforcement and the coach can be instrumental in helping achieve this. If the individual returns from a course with new skills and knowledge, for instance, it is vital for the coach to discuss it. Together, they check what has been learned, what else needs to be done, how the coach can support the development and how much of their plan has been accomplished. Opportunity to practice is essential.

Types of coaching include:

- Individual versus Group Coaching: Coaching is primarily a 1:1 activity and most managers generally coach on an individual basis. However, coaching can also take place with groups or teams, since some people find working on a 1:1 basis uncomfortable and are most comfortable with groups or teams. However, in order to be an effective coach, you first need to be comfortable working on a 1:1 basis. Like all skills, it takes practice to increase your competence and feel comfortable with the coaching process

- Hands-On Coaching: “Hands-on” coaching is appropriate than you are training new or inexperienced staff. Your role as a coach is to demonstrate and explain new tasks, activities and procedures and then observe direct reports putting them into practice. Your tone and manner need to be sympathetic, motivational and patient. The hands-on coach will typically say:

- “I am going to tell you exactly what to do”

- “I will show you how to do it”

- “That was good (not so good or indifferent)”

- “Now try it again”.

- Hands-Off Coaching: “Hands-Off” coaching is used with experienced staff or when trying to develop superior performance in someone. You will rely almost entirely on questioning to enable learners to improve and to take responsibility for doing so. At the same time, the learner is developing the mental attitude necessary for success. As a hands-off coach, you will typically say:

- “Can you tell me what your performance objectives are?”

- “How can you improve?”

- “Can you show me?”

- “How does it feel?”

- “Can you imagine what success might be like?”

- “Can you describe it?’”

- Qualifier Coaching: “Qualifier” coaching may be used when helping learners who are studying or training for a professional qualification to develop a specific piece of knowledge or expertise for their studies. As a qualifier coach, you need to:

- Explain clearly the standards and performance criteria required for the specific qualification desired

- Enable the learner to collect appropriate evidence for assessment

- Liaise effectively with other people supporting the learner’s qualification

- Provide the learner with technical input, support or expertise.

The Components of Coaching

The coaching process usually follows a five-stage process:

- Statement of purpose

- Objectives and options

- What is happening now

- Empowering the learner

- Review of performance.

We will briefly describe these components. Later, we will describe the specific components of corrective and developmental coaching and the specific issues that pertain to each one.

Specifying the Purpose

In a coaching relationship, it is important to define the purpose of any coaching session for those involved. For example:

- “How much time have we got?”

- “What is the purpose of this session of you?”

- “What are you looking for from me?”

- “What can I not coach you on?”

It is important to spell out exactly what the learner sees as the purpose of each coaching session, rather than the coach prescribing it. If the learner encounters difficulties answering these questions, then the coach should help the individual to clarify the learning purpose before embarking on any actual coaching. This helps create a sense of ownership in the learner in his/her own development.

Exploring Objectives and Options

It is important for the learner to identify his/her own objective(s), option(s) and indeed goal(s). Your role as coach must be to keep the learner on track and help them to measure progress – but the goals must be relevant and realistic and owned by the individual.

A trusting and honest relationship between you and the learner is fundamental, if real progress is to be made towards the achievement of goals. You should help the learner to identify their objectives by asking questions, such as:

- “What is your ultimate goal?”

- “How realistic is that objective?”

- “What do you want to achieve in the short- /medium- /long-term?”

- “When do you need to achieve this goal by?”

- “Is it realistic?”

- “How will we measure your progress?”

- “What will you feel like when you achieve your goal?”

- “What would achieving this goal mean to you?”

In asking these questions, you act as a motivator in building enthusiasm for the personal benefits that the learner will gain from the coaching. The agreed objectives should be SMART:

- Specific: The objective should clearly state exactly what the learner should be able to do after completing the activity

- Measurable: The objective should indicate a measurable level of performance the learner is required to achieve

- Achievable: The target should be realistic and attainable

- Relevant: The target should be appropriate to the situation

- Time-bound: The goal should include the timescale over which the change should occur.

The Focus of the Coaching Session

Once you and your learner have begun with an objective or goal in mind, both of you need to establish the current level of performance. You need to ask judgemental questions that help to raise the awareness of your learner and focus him/her focus on the gap between the current and the desired level of performance. You need to pay close attention to the answers, and to explore further with the learner, if the responses are not specific enough. The following are examples of questions you can use for this “reality check”:

- “What is happening now?”

- “What has been done so far?”

- “Who is involved?”

- “What is your contribution?”

- “What are the current results?”

- “What stopped you from achieving more?”

- “What are the barriers in relation to your goal?”

- “What, if anything, have you done to overcome these obstacles?”

- “What would you do differently now?”

- “What are the opportunities open to you in relation to your goal?”

- “On a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate your current level of performance?”

Open questions encourage the learner to dig deep within him/herself and not rely on you to come up with all the answers. They can be supported or followed-up with questions to explore further.

Empowering your Learner

Empowerment is a way of giving more responsibility to your learner. As coach, you must remain accountable for the overall results and the performance of your learners. However, from the commencement of coaching, it should be the learner who is primarily responsible for his or her own development. Learners who are empowered in a coaching situation can identify what objectives they need to meet and therefore what options they have in order to close the gap between their current performance and the desired performance.

Empowering questions in a coaching context include:

- “What are the different alternatives?”

- “What else could you do to improve your performance?”

- “What options do you have?”

- “What are the pros and cons of each option?”

- “Which would give the best results?”

- “Would you like a suggestion?”

- “What would you do differently if you could start all over again?”

- “How much trust do you have in your ability to do it?”

- “On a scale of 1 to 10, what is the likelihood of your succeeding with this idea?”

- “What are here advantages / disadvantages of this approach?”

- “What plan of action will you implement?”

- “How can I (the coach) help you?”

You will need good interpersonal skills to help a learner through these empowering questions. It is advisable to start on a positive footing and to ask what has worked so far. Out of empowering should come an agreed plan of new tasks, actions and activities of the learner to carry out.

Review of Coaching Session

You will need to observe and review the learner’s performance and compare it against an agreed standard. You should offer constructive feedback and ensure that such reviews are on-going.

Typical questions to ask during a review include:

- “What were you trying to achieve?”

- “What worked well for you during the performance?”

- “What could have gone better?”

- “What would you do differently the next time?”

- “What are the next steps in your action plan?”

Finally, your coaching style should be designed to build self-confidence and in particular to encourage learner autonomy.

Coaching has the potential to offer numerous benefits to the learner, the coach, the training department and the organisation. Figure 10.4 is a summary of the key benefits that you can articulate in order to justify the implementation of a coaching strategy.

FIGURE 10.4: BENEFITS OF COACHING

Learner

- The recognition of the importance of the line manager

- The development of their skills

- Higher job satisfaction, as they improve their performance

- Greater interest in, and sense of responsibility for, their work

- A growing ability to take on a greater variety of tasks

Coach

- A more successful and productive department / team

- Greater confidence when delegating tasks to your staff

- Development of your own management skills

- A growing reputation as a “developer of people”

- Exposure to new ideas and perspectives from your staff

Organisation

- Encourages instant and ongoing feedback about performance

- Improves manager and staff relationships and communications

- Provides a cost-effective means of staff development

- Greater value for money from formal training

Training Department

- Encourages line managers to think about their T&D role

- Takes the emphasis away from formal, course-based learning

- Enhances the learning transfer process and potentially enhances the status of the training function

- It takes some of the burden off you as a trainer

- It facilitates a speedy response to learning and training needs

- A realisation that the training department must act in partnership with line managers and learners

We now consider two coaching situations: corrective and developmental.

Conducting Corrective Coaching

Corrective coaching is an important dimension of a manager’s role because it focuses on developing skills for effective performance in your organisation. It involves meeting with your direct report where you focus on correcting a pattern of behaviour and improving overall job performance. Corrective coaching is important because, if it is used effectively and not just at performance review time, it can lead to significant improvements in individual job performance. Most important from the manager’s point of view, corrective coaching can prevent small problems developing into big ones.

Corrective coaching has three major advantages for the manager:

- It is a tool for giving regular and direct feedback to your direct reports. Through coaching, you can keep direct reports “on track” with their regular assignments and the special tasks or projects you have delegated to them

- It is a source of information and skills. You can learn more about, and from, your direct reports because good corrective coaching involves two-way communication. By using constructive feedback in coaching sessions, you can also encourage the development of positive work relationships

- It provides opportunities for you to develop and practise your interpersonal and management skills.

It is important that corrective coaching has benefits for your direct reports. Three specific benefits can be identified:

- Direct feedback on performance problems and opportunities for improvement. If you coach constructively, direct reports can turn a mistake or work problem into a learning situation

- Stimulus to direct reports who may just be cruising along. Corrective coaching shows your concern for what the direct report is doing and your attention can improve their performance

- Opportunities for employees to develop their own problem-solving skills. A good coach will not impose solutions but, through discussion, will help direct reports to sort out their own problems and make better decisions.

Figure 10.5 provides a summary of corrective coaching guidelines that may be followed by the manager or by a trainer when they are required to perform a corrective coaching role.

FIGURE 10.5: CONDUCTING CORRECTIVE COACHING: GUIDELINES FOR ACTION

1.Identifying Coaching Goals: Before you discuss a performance problem with a direct report, take the time you need to plan and prepare. Decide what you want to accomplish through the coaching session – what are the specific outcomes you want to see, such as the direct report making a specific commitment to change or improve something

2.Prepare for Coaching Session: Gather the information that you need, decide upon the time/place for your discussion and communicate this to the direct report

3.Express your Desire to Help: Welcome the direct report and explain that you want to ensure good two-way communication in the workplace. This meeting is an opportunity to clarify and discuss your own and your direct report’s expectations and views. Begin by focusing on positives – informing your direct report that you appreciate the things they do well makes them more open to receiving feedback on performance problems

4.State the Problem and its Consequences: Based on the facts of the situation, describe the problem that has led to this coaching session. At the beginning of the session, it is important to be objective and factual and to use descriptive rather than evaluative statements. Be relaxed and open-minded. Don’t jump to conclusions and be prepared to discuss the direct report’s expectations. After stating the problem you might refer to some of the consequences – for example, other people being affected, work delayed, customers upset, and so on. You should not overlook your own feelings as they relate to the issue – what has been the impact of this problem on you – and share those feelings

5.Reach Agreement that a Problem Exists: Obtaining the direct report’s agreement that a problem exists is the most important, and often the most difficult step, in the corrective coaching process. If you continue without gaining agreement, additional difficulties will arise and you may need to return again to try to secure agreement. One way of gaining agreement is to point out the gap between the standard or what you expect and the person’s actions and behaviour. Once you have agreement that a problem exists, emphasise this agreement so that it is clear to the direct report

6.Discuss Causes of the Problem: Determine the facts by asking information questions like “What happened …”, “What time …”, “Why did you do that?”. Encourage the direct report to talk about the problem while you listen and try to see the situation from his/her point of view. In addition to asking questions, you might steer the coaching session by interrupting occasionally and using reflective statements such as: “So you think that …”, “Does this mean that …”. These statements reflect back to direct reports the picture they are presenting and check your understanding of what has been said. They may also stimulate your direct report to expand on a point or help you guide them to the next stage in the coaching session

7.Discuss Possible Solutions and their Benefits: Move the discussion from talking about the past to talking about the future, from talking about things that have gone wrong to how to prevent them from going wrong again. With a direct report who needs more direction, you may narrow down the possible solutions by discussing two or three options: “Which do you think would be better …?”. Don’t forget to discuss how the direct report will benefit from taking the actions you suggest

8.Agree upon Actions: On the basis that employees generally respond well to a personal approach, you might tell the direct report something about how you see things and your own experience related to this problem. Here, you can demonstrate your own involvement as a person rather than someone judging at a distance. However, try to avoid telling your direct report that they “should do such and such” or “should have done such and such”. Too many “should”s can make you appear rigid and pedantic. The responsibility for changing his/her behaviour is not yours: it lies with the individual. This is why your direct reports needs to be involved in making decisions and agreeing upon future action. In this way, he/she will be more committed to these decisions or actions. End this session on an encouraging note and show how direct reports can benefit from taking the actions agreed upon. Identify a target for future performance and arrange to discuss the issue again at a future date so that you can provide support and monitor progress

9.Document the Session: You need to document the session. Then you will have a record to refer back to later, particularly if there are any further coaching sessions or if disciplinary action may be necessary. Document the solutions or actions agreed upon and the date of the follow-up meeting

10. Follow-up on the Session: Consider how you might follow-up on the corrective coaching session. When and how often do you need to check on progress? How will you recognise achievement or change? If you reward the behaviour, is it most likely to be repeated? What will you do if the problem continues?

Created from Beard and Wilson (2002), Sheal (1999) and Evenden and Anderson (1992).

Developmental Coaching

Some of the skills we have discussed in respect of corrective coaching equally apply to developmental coaching, although a number of additional considerations apply to the effective implementation of developmental coaching:

- Customisation of the Coaching Relationship: Coaching can be customised to the unique needs of the direct report / learner being coached. Both the content (what is learned) and the process (when, where and how it is learned) can be customised. Thus, unique needs can be met in one process. Another consideration in choosing coaching is how well a customised learning approach fits with the organisational culture

- Just-in-Time Coaching: When the development need is urgent, coaching can be arranged more quickly than other learning modes such as classroom training, university courses, or action learning

- The Value of Coaching: Coaching is recommended when an employee’s time is more valuable than the cost, such as with senior executives, financial gurus, and other key individuals. Coaching tends to provide the maximum learning for the time invested, because the learning is continuously tailored exactly to the topics and the level of the person being coached

- Confidentiality: Coaching generally takes place in the context of a close, trusting relationship, where it is safe to discuss sensitive personal and business issues. For managers, in particular, it provides a confidential and objective sounding board for issues that they may be reluctant or unable to discuss with other members of their team

- Skill Focus of Coaching: Developing coaching is a particular useful way of enhancing a range of skills such as the following:

- Interpersonal skills, including relationship building, tact and sensitivity, assertiveness, conflict management, working across cultures, and influencing without authority

- Communication, including listening skills, presentations, and speaking with impact

- Leadership skills, including delegating, coaching and mentoring, and motivating others

- Certain cognitive skills, such as prioritising, decision-making, and strategic thinking

- Self-management skills, including time management, emotion and anger management and work-life balance.

Figure 10.6 sets out what you need to consider when establishing a developmental coaching relationship.

FIGURE 10.6: DEVELOPMENTAL COACHING: DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

Identifying the Learners who will Benefit from Coaching

Organisations should develop specific criteria for determining who will receive coaching. The following questions should be considered when selecting learners:

- Is there a genuine development need?

- Is that development need linked to business performance?

- Is the issue something the individual has control over, or is it symptomatic of a larger organisational problem that needs to be addressed on a broader scale?

- Is the person open to learning and feedback?

- Is the person motivated to learn and change?

- Is coaching the most appropriate development solution given your understanding of the problem?

Selecting and Training the Coach

An effective coach requires two key qualities:

1.It is important to make sure that the coach can relate to the person and the world that person lives in. Find out how well the coach has worked with others in similar situations by asking the following questions:

- What kinds of people have you worked with? What results did you achieve?

- Where do you do your best work? With what kinds of people and topics do you work best?

- Who would you turn down and why?

2.A coach should be able to walk a person through all the important steps of learning. The following questions are useful in assessing a coach’s appropriateness to the learning process:

- How will you determine what the person needs to work on?

- How will you help the person learn new ways to do things?

- How will you ensure they get results?

You may consider using either an external or internal coach. External coaches are most appropriate:

- When you need rapid learning and behaviour change. Few organisations have internal coaches with the depth of skill and experience that is readily available among external coaches. This is especially the case for management development

- For dealing with direct reports who are resistant to change or who are cynical toward the coaching process. There is less risk if an external person fails as a coach

- For relatively confidential or sensitive issues, where the person does not want an internal person involved

- When internal coaches are unavailable or in different locations.

- When internal coaches do not have the particular expertise that is desired

- When an objective, independent viewpoint is critical

In contrast, internal coaches are most appropriate in these cases:

- As part of regular, ongoing development activities, such as supporting a specific development programme

- When deep knowledge of the personalities or relationships among a given cast of characters is important

- When knowledge of organisational politics or how things really get done inside the organisation is critical

Initiate the Coaching Relationship

Contracting: There are several aspects of contracting:

- The first focuses on the content, outlining the purpose of the coaching, establishing specific learning goals, and setting clear expectations for how and when performance will improve

- The second is procedural, defining various stakeholders and their roles, as well as clarifying guidelines for confidentiality and communications

- Finally, contracting involves financial arrangements, such as fees, expenses, and billing schedules in the case of an external coach.

The contracting process can begin by identifying the key stakeholders, usually the coach, the person being coached, that person’s immediate superior or designated organisational sponsor, and an appropriate human resource contact. The coach should discuss expectations, roles and responsibilities with each stakeholder.

Coaching Sessions: There are typically three parts to an effective coaching session:

- The Opening: In the very first meeting, the opening is a chance to clarify expectations, solidify the working agenda, and get to know each other. This may be the first time the coach and the participant meet face-to-face, although they have usually been in communication with each other in arranging the coaching process. The coach needs to pay particular attention to building trust and rapport by understanding what the person hopes to accomplish through coaching. In subsequent meetings, the first part of each session allows time to re-establish that rapport, catch up on what has happened since the last session, and prioritise the agenda for the day

- Practice: The middle segment is the heart of the coaching process. Here, through hands-on practice of real-world situations, instruction, modelling, feedback, and discussion, the coach facilitates the kind of learning that participants can carry back with them to the workplace

- Action Planning: It is relatively easy for participants to leave each session with new insights and skills and a genuine motivation to put them into action. Participants should visualise exactly what will happen when they try to put a new behaviour into action. When do they plan to do it? How will they remember to do it? What will get in their way? What will they do to stay on track? How will they evaluate the outcome of their new action? How will they get feedback from others? When will they try it again? How will they modify or build on what they tried the next time they use it?

Development Activities Between Sessions: Between coaching sessions, participants are expected to apply what they have learned. Attention to this is essential for breaking old habits and establishing new ones. Participants need to be encouraged to push their comfort zone on a daily basis.

Created from Kraiger (2001), Evenden and Anderson (1992) and Gunnigle (1999).

Corrective versus Developmental Coaching

It is likely that in your role as manager you will perform both corrective and developmental coaching. Both processes have the potential to develop the employee. Figure 10.7 provides a summary of the assumptions and differences between corrective and developmental coaching.

FIGURE 10.7: DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CORRECTIVE & DEVELOPMENTAL COACHING

The Manager as Mentor

A mentor is usually a more experienced and senior person than the mentee. Mentors are likely to be technical or professional experts or middle or senior managers and are more frequently drawn from within the organisation.

Mentors usually perform a number of important roles. Typically, they provide one or more of the following:

- Guidance on how to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to do a new job

- Advice on dealing with any administrative, technical or “people” problems

- Information on “the way things are done around here” – the culture and its manifestations in the shape of core values and organisational behaviour

- Help in obtaining access to information and people within the organisation

- Coaching in specific skills, especially managerial skills such as leadership, communications and time management

- Help in completing projects – not by doing it for the mentee but by helping them to help themselves

- A parental figure, with whom mentees can discuss their aspirations and concerns, and who will lend a sympathetic ear to their problems.

There are a number of roles that mentors may have to fulfil:

- Mentor as Coach: Coaching can help in developing new skills in the mentee, can give constructive and considered feedback and can offer an insight into management practice. It works best when the mentor is supportive and offers friendly encouragement

- Mentor as Counsellor: Counselling can help mentees explore and resolve problems and difficulties they may be facing in a confidential setting. However, it is important to remember that you are not a trained counsellor and any issues that you cannot handle should be passed to an expert

- Mentor as Role Model: Mentors, by their behaviour, can demonstrate the acceptable standards of conduct and impart “the way things are done around here”, particularly in the case of new recruits. They can also be seen as someone who has “trodden the path” already.

It is important that the focus of the mentoring is on helping the mentee to learn. While direct advice and instruction from the mentor can be helpful, it is important to ensure that mentees learn to think for themselves and that the mentoring process does not, either intentionally or unintentionally, create a dependence where they just blindly follow the mentor’s instructions and cannot take action without advice.

Mentoring is likely to suit managers who are interested in the development of others and who enjoy sharing their knowledge and experience with them. Not all managers are likely to make good mentors. It requires a considerable amount of time commitment, emotional resources and sustained effort.

Selecting Mentors and Initiating a Programme

There are a number of issues that you and your organisation should consider implementing a mentoring programme.

Selection of Mentors

This is a critical task, because it determines the success of the programme. You should select as mentors those who are interested in other people and, in particular, in their development. When choosing a mentor, the following qualities are important: experience, breadth of knowledge, technical proficiency, credibility, respect for confidentiality and status. The mentor needs to be completely trustworthy, so that it is possible for the mentee to discuss career and personal issues knowing that they will be held in strict confidence.

If the right kind of mentor does not exist in your organisation, you should look outside. You can find mentors in universities, colleges, similar organisations, or your own professional association. Most people worry about asking someone to mentor them without remuneration. Remember that most people consider it a privilege to help others develop and are flattered to be asked to participate in other people’s career development. They understand that being asked to act as a mentor is a way of building their own career and profession. The pay-off for the mentor is that as their protégés develop, so will their own network and sphere of influence.

When you are choosing a mentor, the following are some of the questions that need to be asked (from the perspective of the mentee):

- Do I want someone with similar, or contrasting, work experience to me, or a mixture?

- What type of background and experience do they possess?

- Do I want a mentor with a similar, contrasting, or specific management style?

- Do I want to work with someone of the same or a different gender?

- Should they be based in the same building or site, or could I travel easily to another location to meet them?

- Do I want to work with someone with a wide knowledge of the industry or with a deeper understanding in a specialist area?

- Will I have ready access to them, or will they be too busy to meet me at short notice?

- How well do they know my line manager?

Development of Mentor Skills

In order to be an effective mentor, the mentor should be capable of identifying the strengths and opportunities for development of the mentee. The mentor needs to be skilled in motivating the mentee to develop – it may be necessary to have coaching skills to provide specific skill development. The mentor should also be able to provide networking opportunities for the mentee to access other influential people, as well as education and development resources and opportunities. The skilled mentor needs to be able to listen actively, question effectively, understand differences in learning style and adapt their mentoring style to the learning style of the mentee. The mentor may need to challenge assumptions and ensure that they give enough time to the protégé. Mentors need to be self-aware and capable of self-analysis and two-way feedback.

Establishing Ground Rules and Preparing the Mentoring Contract

If your mentoring programme takes place in a formal context, then it may be your role as trainer to make a formal allocation of mentor and mentee. If, however, mentoring takes place on an informal basis, then the mentee will probably have to seek out and approach a suitable mentor. However arrived at, from the perspective of the organisation, it is important that the contractual dimensions of the relationship are made explicit from the outset. Some of the issues include:

- Identify and explore the expectations of both mentor and mentee

- Agree the overall objectives of the mentoring relationship

- Agree on what each other’s roles are within the relationship

- Consider what will be covered and what will not

- Decide how mentor and mentee will give each other feedback

- Discuss any involvement of the mentee’s line manager

- Decide who will be responsible for organising meetings

- Decide when and where mentor and mentee both meet

- Decide on how long mentor and mentee will generally meet for

- Discuss on-going informal contact with each other

- Agree on the structure for mentoring meetings

- Agree on the breadth of confidentiality

- Decide on the overall duration of the relationship

- Agree on an opt-out clause after a certain timeframe (usually three months), if the relationship is not working out

- Decide on the processes to be used when there are disagreements and conflicts.

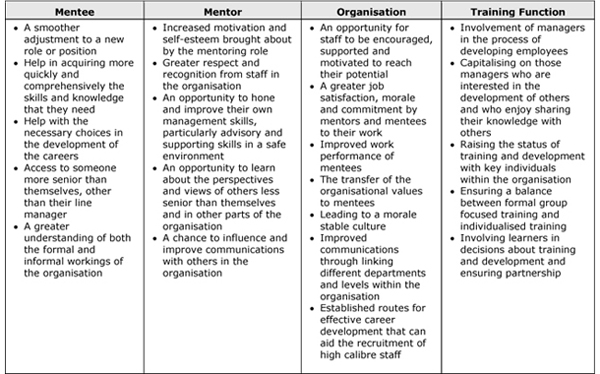

Benefits of Mentoring

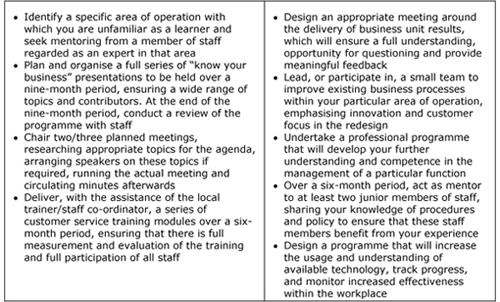

Mentoring can bring benefits to the manager who performs the role of mentor, the learner as mentee or protégé, and the organisation – generally, and particularly to the training function. Figure 10.8 summarises the benefits for all of the parties.

FIGURE 10.8: BENEFITS OF MENTORING

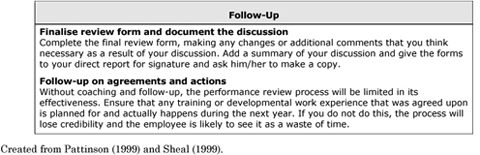

FIGURE 10.9: EFFECTIVE MENTORING: PRACTICE GUIDELINES

Identify Mentoring Needs: You need to consider the current situation. What are your department’s needs in terms of career planning, graduate development, job certification or vocational qualifications? What do individual members of staff need to learn during the next year? What do your new employees need to learn? Who needs to learn a new skill? Who can teach particular skills?

Assess Whether Mentoring will Work: Are the conditions for a mentoring relationship favourable? If there is a lack of management commitment, you or someone else could make a presentation on mentoring. If there are no rewards for mentoring currently, your organisation might find a way to reward mentors through the performance review system or some other recognition process

Identifying the Potential Mentor: As you think about your staff, try to match your potential mentors and those who need to learn. The best matches occur between mentors and staff who share similar jobs, and work in close proximity to each other so they can easily get together. You should identify managers who are already functioning as informal mentors – managers who seem to have the motivation and some experience of mentoring. You might also consider which of your senior management team might benefit from taking on mentoring responsibilities

Discuss with Potential Mentor: Meet with the potential mentor and discuss the purpose and benefits of a mentoring relationship. At the beginning, you need to find out whether the person really wants to be a mentor. Mentors and mentees should always be volunteers. Not all experienced staff may wish to share their know-how. Indeed, some may enjoy the advantage that superior knowledge gives them and want to withhold important job information. If you think this might be the case, you should not use that person as a mentor, or explain very clearly what is required and monitor the mentoring relationship carefully. You also need to draw out any concerns or fears the prospective mentor might have. If these concerns are not discussed at the start, they can undermine the process

Discuss with the Mentee: You should meet with the employee(s) to be mentored. Discuss their strengths, interests, specific skills that may need to be developed. Explain the purpose and benefits of mentoring as a development tool. Mentoring involves people working together, it is a mutual exchange, and employees should know that they are just as responsible for the success of mentoring relationship as the mentor. In particular, mentees must be prepared to consider their own areas for improvement and be willing to learn. The motivation of the mentee to learn is an important judgement call that you will have to make

Arrange for Training: To ensure that the mentoring relationship gets off to a good start, it’s useful for both mentors and mentees to attend a briefing or introduction to the mentoring process. By working together on tasks like needs assessment and development planning, both parties can forge their working relationship, clarify expectations, and ensure that they are “singing from the same sheet”

Agree Development Plan: Work on the mentees’ development plans might start at the briefing session or the introduction to the mentoring process. These discussions between the mentors and mentees often need more time and require consultation with other people involved – for example, the mentees’ supervisors, the training or personnel departments, or other organisations where mentees may have a field trip or short assignment

The Initial Meeting: The first meeting is very important. Mentor and mentee should find out about each other in terms of general background, professional training, time in the organisation, career history, key skills and knowledge. It is important that all elements of the mentoring contract are clearly agreed upon. It is recommended that the initial meeting should occur on a four to six week basis for the first six months to establish the mentoring relationship. Every effort should be made by both parties to keep to the meeting schedule. The duration each meeting should be for 1 to 2 hours per month.

Structuring Follow-Up Meetings: The overall duration of a formal mentoring relationship tends to be from six months to two years. It is desirable that it be for at least six months. In between meetings, both mentor and mentee should contact each other to check on progress, ask questions and deal with any relevant issues. When mentor and mentee meet for the next and subsequent meetings, the following issues should be considered:

- Decide and agree what you want to get out of the meeting

- Review progress since the last meeting

- Establish what has been learnt

- Focus on making progress on a specific issue:

- Establish what the issue is

- Explore what is causing it

- Consider it and discuss possible ways forward

- Seek suggestions and, if needed, offer advice

- Agree a way forward

- Summarise conclusions and actions

- Agree on a time and place for the next meeting.

Adapted from O’Connor (1999).

Problems with Formal Mentoring Relationships

The establishment of formal mentoring relationships in organisations is a difficult one. It is not uncommon for mentoring relationships to fail or to under-perform, for reasons that include:

- One or both members in the relationship find it difficult to get along with the other: Mentor or mentee may not like one another because they hold widely differing views, or simply there is a clash of personality. If this arises, then it should be addressed as early as possible – both should review the relationship to date and discuss whether it is with trying to resolve differences and start again, or indeed whether to call on the opt-out clause and agree to part. It may be worth involving another person, such as a member of the personnel department in these discussions and decisions

- Someone breaches a confidence: This can lead to a lack of trust on the part of the other, resulting in an ineffective mentoring relationship. If the spread and depth of confidentiality has not been previously negotiated, then this should be discussed immediately. If a confidentiality clause is already in place, then both mentor and mentee need to sit down and discuss the reasons behind the breach of confidence and how to ensure it does not happen again – there may be a need to renegotiate the mentoring contract again

- Mentoring takes up more time and is more demanding than originally anticipated: If the mentor or mentee cannot commit the necessary time and attention, or is continually cancelling and re-scheduling meetings, particularly at short notice, then frustration is likely to develop. Furthermore, this behaviour will send a negative signal about the importance of the relationship. If this is simply due to poor time and diary management, then revisiting the time aspect of the mentoring contract and agreeing in advance to a programme of meeting dates over a considerable time-frame – say, six months – may work. However, if the reason is a genuine lack of time, then both parties need to consider whether it is worth seeking another mentor/mentee

- Neither party is really interested in maintaining the mentoring relationship: This occurs when the mentor and the mentee become complacent – eventually, the partnership dissolves due to lack of interest. This can arise if the relationship has run its course, in which case the mentoring has reached its natural conclusion. But if this is not the case, then both need to make more of an effort in terms of general input, setting objectives and goals, agreeing action plans and arranging a programme of meetings, etc. in order to maintain a sense of overall purpose to the relationship

- The mentee has unrealistic expectations about what the mentor can offer: The mentee views the mentor as someone of considerable standing in the organisation, and as such, someone who should be able to “pull strings” and really transform their career. When this doesn’t materialise, the mentee may feel annoyed and disillusioned. Mentors should ensure from the beginning, therefore, that the mentee has a realistic perspective of what the mentor’s role is and what they can and, indeed cannot, do for them. They should never make unrealistic promises or commitments to the mentee that they cannot deliver on.

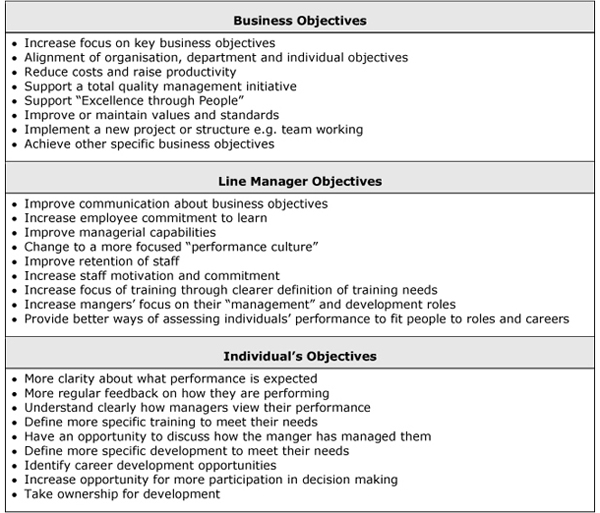

THE MANAGER AS PERFORMANCE MANAGER

The manager has an important role to play in the performance management process. Line managers typically, but not exclusively, operate most performance management processes. Performance management has a number of important objectives for the business, the line manager and the individual, summarised in Figure 10.10.

FIGURE 10.10: OBJECTIVES OF THE PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT PROCESS

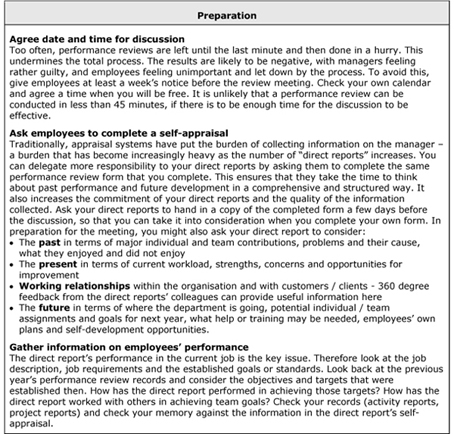

The performance management process usually culminates in an appraisal interview in which the manager and subordinate review the appraisal and make plans to remedy differences and develop strengths.

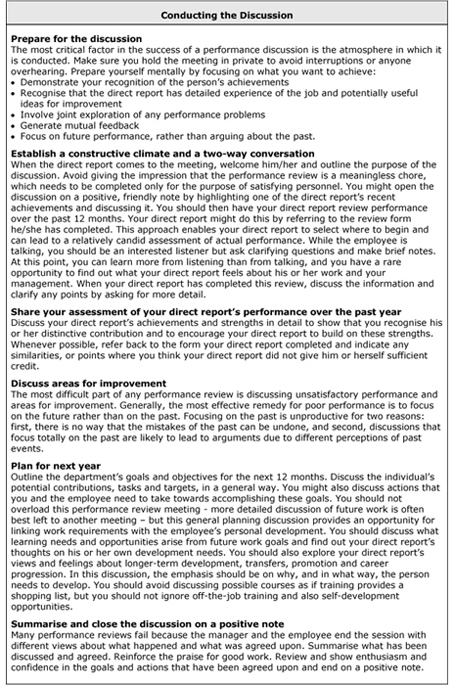

There are a number of issues that you need to be aware of when conducting this discussion:

- Preparation: Effective preparation involves three steps. You should first give the direct report sufficient notice to review his/her work. It is also advisable to read his/her job description, analyse problems or development issues and compile questions and comments. Secondly, you will need to study the job role, compare the employee’s performance to his/her standards and revisit previous reviews. Finally, you should agree an appropriate time/place to conduct the review

- Conducting the Interview: The primary aim of the interview is to reinforce satisfactory performance, to address unsatisfactory performance and to plan for future development. It is important that you check the determinants of performance or behaviour that apply to the performance situation you are analysing. Some of the issues that you need to consider here are presented in Figure 10.5. You will need to be direct and specific. You should talk in terms of objective work data, using examples to support your arguments. Before your direct report leaves, you will need to get agreement on how things can be improved.

It is also important that you are conscious of the possible rating errors you can make in a performance appraisal, which have the potential to significantly undermine the effectiveness of your performance discussion. These include:

- Halo and Horn: A tendency to think of an employee as more or less good or bad is carried over into specific performance ratings. Stereotypes based on the employee’s sex, race, or age also affect performance ratings. In either case, the rater does not make meaningful distinctions when evaluating specific dimensions of performance – all are rated either low (horn) or high (halo)

- Leniency: All employees are rated higher than they should be. This happens when managers are not penalised for giving high ratings to everyone, when rewards are not part of a fixed and limited pot, and when dimensions ratings are not required

- Strictness: All employees are related lower than they should be. Inexperienced raters unfamiliar with environmental constraints on performance, raters with low self-esteem, and raters who have themselves received a low rating are most likely to rate strictly. Rater-training that includes a reversal of supervisor-incumbent roles and confidence building can reduce this error

- Central Tendency: All employees are rated as average, when performance actually varies. Raters with large spans of control and little opportunity to observe behaviour are likely to use this “play safe” strategy. A forced distribution format requiring that most employees be rated average also may create this error

- Primacy: As a cognitive shortcut, raters may use initial information to categorise a person as either a good or a bad performer. Information that supports the initial judgement is amassed, and contradicting information is ignored

- Recency: A rater may ignore employee performance until the appraisal data draws near. When the rater searches for cues about performance, recent behaviours or results are most salient, so recent events receive more weight than they should

- Contrast Effects: When compared with weak employees, an average employee will appear outstanding, when evaluated against outstanding employees, an average employee will be perceived as a low performer.

The performance management process has a major developmental component. There are a number of important benefits to be gained by the manager and direct report, if performance reviews are used effectively as a development tool.

FIGURE 10.11: CHECKLIST FOR DIAGNOSING THE CAUSES OF EMPLOYEE PERFORMANCE DEFICIENCIES

Check the determinants of performance or behaviour that apply to the situation you are analysing.

Competencies / Skills

- Does the direct report have the competencies needed to perform as expected?

- Has the direct report performed as expected before?

- Does the direct report believe he or she has the competencies needed to perform as desired?

- Does the direct report have the interest to perform as desired?

Goals of the Direct report

- Were the goals communicated to the direct report?

- Are the goals specific?

- Are the goals difficult but attainable?

Certainty for the Direct report

- Has desired performance been clearly specified?

- Have rewards or consequences for good or bad performance been specified?

- Is the direct report clear about her or his level of authority?

Feedback to the Direct report

- Does the direct report know when he or she has performed correctly or incorrectly?

- Is the feedback diagnostic so that the direct report can perform better in the future?

- Is there a delay between performance and the receipt of the feedback?

- Can performance feedback be easily interpreted?

Consequences to the Direct report

- Is performing as expected punishing on the direct report?

- Is not performing poorly more rewarding than performing well?

- Does performing as desired matter?

- Are there positive consequences for performing as desired?

Power for the Direct report

- Can the direct report mobilise the resources to get the job done?

- Does the direct report have the tools and equipment to perform as desired?

- Is performance under the control of the direct report?

The benefits that the manager can receive from the process include:

- The opportunity to learn about a direct report’s hopes, fears, anxieties and careers related to both the present job and the future career

- The opportunity to clarify and reinforce important goals and priorities so the direct report can see precisely where their contribution fits in

- The opportunity to motivate staff by recognising important achievements

- Performance review provides a basis for discussing and agreeing upon courses of action to develop employee performance and contribute to organisational performance.

From the perspective of the direct report, the benefits include:

- An opportunity to receive feedback from a manager on how the direct report’s performance is viewed by the organisation

- A forum for agreeing with a manager a plan for overcoming barriers to performance and for enhancing performance in the future

- An opportunity to communicate views about the job to a manager

- An effective process within which to identify the direct report’s training and development needs and agree on appropriate actions to implement these needs.

Where you use performance reviews in a developmental context should be aware of the issues summarised in Figure 10.12.

FIGURE 10.12: GUIDELINES FOR USING PERFORMANCE REVIEWS IN A DEVELOPMENTAL CONTEXT

Using Multi-source Feedback for Development

The major goal of a multi-source feedback intervention is to facilitate change and development in individual or team behaviour. A multi-source feedback intervention involves the systematic collection of specific information from multiple sources to enhance the self-awareness of individuals and teams. Focus groups, interviews, or paper-and-pencil instruments are used to obtain data from multiple sources that have a relevant perspective to share. These data are summarised quantitatively or qualitatively, and are then shared orally or in writing with one or more members of the organisation.

The most common form of multi-source feedback interventions typically uses an off-the-shelf or in-house designed instrument that measures critical competencies required for competitive performance. Most feedback from these interventions is collected from multiple perspectives (for example, an individual’s supervisor, direct reports, peers and team members) and is summarised in the form of a written or computerised report (often including graphic comparisons of the perceptions of the individual and others, written comments, and narrative information.

The interventions based on multi-source feedback that are most commonly used are:

- Executive and management coaching

- Training and development

- Career counselling

- Succession planning and development

- Training needs assessment

- Training evaluation

- Performance appraisal and evaluation.

If your organisation is considering using a multi-source feedback process, then you must be clear concerning the situations in which it is appropriate and not appropriate.

The use of multi-source feedback is a valuable tool in the following situations:

- Behavioural Change in Individuals and Teams: A multi-source feedback intervention is useful in providing individuals and team members with specific information from multiple perspectives abut strengths and areas for development. This information increases self-insight and self-awareness and becomes a catalyst for behavioural change efforts.

- Self-Awareness Issues: It is not uncommon for an individual to lack insight about the impact that he/she has on others or about the way others perceive him/her. A multi-source feedback intervention helps individual team members to compare their perceptions of themselves to those of others. Multi-rater feedback has been shown to increase self-awareness and insight for both individual and teams, often resulting in successful behavioural change efforts

- When Multiple Perspectives Provide a Holistic Picture: Although research suggests that agreement among multiple sources may be at best modest, different perspectives provide the respondent with information about how he/she is perceived and the impact that he/she has on internal and external stakeholders.

There is evidence that line managers may be anxious about receiving feedback on their performance from peers and subordinates. Coping with criticism is often difficult, and is likely to be particularly so if opportunities for open communication between line managers and their subordinates are not the norm. One method used by organisations to manage feedback is through the use of a “neutral intermediary” – an individual who is skilled in providing such feedback but is not a close acquaintance of either the line manager or his or her assessors. The feedback can be put into context by collecting the multi-source appraisal results for all managers in key areas, and then comparing individual performance against the common findings within that department or across the entire organisation.

There are a number of difficulties that can be associated with multi-source appraisal processes, including:

- Survey fatigue – appraisers may tire of having to complete forms for all of the peers, subordinates and subordinates with whom they are associated

- Friends of appraisees may present a flattering but unrealistic assessment in order to avoid hurt feelings

- Evaluators are not always nice or positive and may use multi-source appraisal as an opportunity to criticise others

- Unless training and briefing are adequate, feedback may not be accurate, reliable or truthful

- Managers ignore the feedback and nothing changes.

You can enhance the effectiveness of multi-source feedback by:

- Anonymous and confidential feedback, often using a specialist external consultant

- Considering the length of time the appraisee has spent in the position: if it is less than six months, consider using the first appraisal as a benchmark only for a follow-up appraisal

- Using a feedback expert to “interpret” the feedback and remove all the jargon and unnecessary statistics so that it can be easily understood by the appraisee

- Following-up and developing action plans for “low scoring” areas: improvements should be assessed six months to a year later

- Using written descriptions, as well as numerical ratings, as feedback because they are likely to be more meaningful to the appraisee

- Ensuring that the feedback data collection method is reliable, valid and based on sound statistical methods

- Avoiding survey fatigue by not using multi-source appraisal on too many employees at the same time.

It is not advisable to use a multi-source feedback process :

- When a high level of defensiveness exists on the part of the feedback recipient

- When individual raters, other than the feedback recipient’s supervisor, can be identified (when anonymity cannot be maintained)

- When the feedback results will be used in a manner other than initially intended

- When the intervention would be used by practitioners with limited or no training in handling multi-source feedback

- In organisational cultures that do not support, reinforce, and encourage open and honest two-way feedback.

Some organisations now use multi-source feedback processes as a performance review and development tool. We do not propose to give it major consideration here, although Figure 10.13 provides a brief summary of the issues concerned with the use of 360-degree feedback as a performance management development tool.

FIGURE 10.13: MULTI-SOURCE FEEDBACK & DEVELOPMENT

Multi-source feedback reveals how successful an individual is in all-important work relationships. The person’s manager, supervisor, colleagues and direct reports complete individual questionnaires rating his/her competencies and also give written descriptive feedback, where appropriate. These individual questionnaires are collated. The resulting feedback report gives the employee an opportunity to find out how others “see” him or her at work.

Increasingly, multi-source is being used as a tool in development. The advantages of this are:

- Communication of the core competencies the organisation wants to develop. The multi-source lets people know what behaviours and skills are considered important. For example, organisations launching a change process might emphasise continuous improvement, self-development and teamwork in their multi-source questionnaires

- Multiple levels and sources of data should lead to a more objective assessment of a person’s contributions, strengths and development needs

- Higher levels of trust in the fairness of the process. Data from organisations using multi-source indicates that people are more satisfied with ratings from multiple sources than from one person alone. When you hear the same things from different people, you are more likely to change your behaviour

- Making the multi-source part of the performance review gives it some “teeth” – it sends the message that the organisation takes this seriously.

Despite important advantages, there are potential areas for concern:

- Using multi-source can affect trust. Some people fear that a person’s manager could misinterpret the consequences if they give negative feedback. The result can be low quality, or not very useful, feedback

- Staff become less ready to accept multi-source feedback if it seems too negative and has possibly damaging consequences in the performance review process

- Multi-source provides more perspectives on an individual’s performance and development needs but there may still be bias. Degree of agreement measures can be used in the scoring so that high degrees of agreement between raters are highlighted

- The multi-source process can be expensive and the demands of running 360-degree reviews annually as part of the performance review are considerable. Rating fatigue sets in, when everyone has 10 or more questionnaires to compete and the process quickly loses effectiveness and credibility.

Source: Garavan et al. (1997).

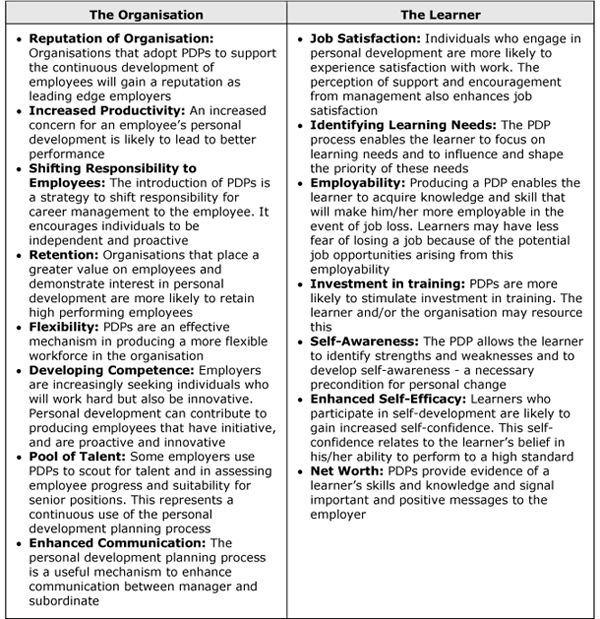

PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT PLANS