11: COSTING TRAINING & MEASURING RETURN ON INVESTMENT

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the distinction between learning costs, training costs and opportunity costs

- Understand the nature of costs as understood by accountants, and distinguish between direct, indirect and full cost concepts

- Explain the main stages involved in calculating the costs of training

- Use a number of formulae and frameworks to calculate of different categories of training costs

- Develop an appropriate cost classification system to track and keep an accurate record of training costs for budgetary purposes

- Identify the steps you should follow when preparing a training budget

- Calculate the financial return on investment in training

- Publicise the results of training and market the benefits within your organisation.

INTRODUCTION

Two important skill areas that you will need to acquire competence in to become an effective trainer are:

- Costing your training and preparing a training budget

- Measuring the return on your training investment.

These two issues concern us in this chapter.

Any training and development activity you undertake has an expense (cost) and an asset (benefit) component. It is relatively easy to understand how a training course may be considered as an expense in strict accounting terms. It is less easy to identify and understand how it may be viewed as an asset.

Under strict accounting rules, if the benefits of any T&D activities that you undertake all arise in the current year, the expenditure must be treated as an expense – there is no future benefit to carry forward as an asset. However, if you can demonstrate that expenditure on T&D activities in the current year will give rise to benefits in a future accounting year, the costs of such activities (or part of them) may be carried forward as an asset.

Your skill in costing a learning activity is an important part of your overall effectiveness as a trainer. Inputs to your training process can usually be costed with a significant degree of accuracy, although you will need good information systems to cost your training effectively. You will have to make a judgement about how detailed your costing of training activities should be. It is generally recommended that, at a minimum, you should include:

- The direct personnel costs of participants and trainers

- The development costs of identifying and analysing training needs

- The direct resource and direct accommodation costs.

You should also be concerned with the return on investment that your training provides. There are several ways that this return can be measured.

In many instances, a group of employees are trained together, so the amount invested is the total cost of analysis, development, delivery and evaluation of the whole development programme. The benefits are then calculated by assigning financial data to areas such as improved employee morale or their improved attitudes. This can be difficult, but is not impossible. We will outline later in this chapter how you may go about this task.

DISTINGUISHING LEARNING COSTS, TRAINING COSTS & OPPORTUNITY COSTS

We make a distinction between learning costs, training costs and opportunity costs.

Learning Costs

Irrespective of the type of training activity you undertake, there is still a cost to be borne by the organisation as a result of employees having to learn their jobs. The costs you incur in providing unsystematic or unplanned training are normally termed “learning costs”. In the absence of formal training, this learning cost will be incurred, simply because employees are on full pay, at the going rate, when they are first learning their jobs. It is very rare to find that pay is adjusted downward to take account of a reduced level of output. The following are considered the main elements of learning costs:

- Payments to employees when learning on the job

- The costs of materials wasted, sales lost or incorrect decisions made by employees who are less than competent

- Supervision/management cost in dealing with “incompetence” problems

- Costs of reduced output/sales caused by the negative effect on an established team of having members who are less than competent

- Cost attributable to accidents caused by lack of “know-how”

- Cost resulting from employees leaving – either because they find the work too difficult, or resent the lack of planned learning, or feel they have no prospects.

These learning costs can be minimised, or even replaced by new earnings, through expenditure on training and development.

Training Costs

We define training costs as those deliberately incurred to facilitate learning, and with the intention of reducing learning costs. These costs might be aimed not at planned training per se, but at the learning system. A training intervention might involve investing in appraisal procedures in order to get better data on learning needs – the act of clarifying learning objectives, in itself, might generate some learning. Most training costs are more directly related to planned training itself and are of two kinds:

- Fixed costs: Not expected to change with the amount of training that takes place (salaries of permanent staff)

- Variable costs: Vary directly with the level of training activity (materials used or college fees paid).

The following are examples of training costs you might incur:

- People Costs: Wages, salaries of trainers and instructors / Managers’ or supervisors’ salaries while training or coaching / Fees to external training providers / Fees to external assessors / Fees to assessing bodies for in-house courses / Travel and subsistence of trainees and trainers

- Equipment Costs: Training equipment and aids / Depreciation of training building and equipment

- Admin Costs: Wages and salaries of admin or backup staff / Telephone and postages / Office consumables / System and procedures (post-training questionnaires) / Hire of rooms

- Materials Costs: Films and tapes / Distance learning packages / Materials used in practice sessions / Protective clothing / Books and journals.

On-the job training can incur the costs of additional supervision and the cost of waste or mistakes made by trainees.

Large-scale initial costs relating to buildings or major items of training equipment (a simulator) will normally be “capitalised” – as “fixed assets”, the costs of which are spread over a long term via the annual “depreciation” charge in the company’s profit and loss account. Additionally, the upkeep of a training centre (a purpose maintained building) will incur all the normal costs usually associated with buildings – for example, insurance, cleaning, heating, lighting, decorating and general maintenance. Training and development departments usually will also be required to carry a proportion of the organisation’s overheads.

The relationship between learning costs and training costs should be such that both are minimised, because an expense is justified only if it reduces the costs of unplanned learning. However, the degree of certainty attached to any estimates will vary, and decisions usually have to be made based on incomplete information. This requires that you must set an upper limit in advance – a “budget” on what can be spend in a given period (usually a year).

Opportunity Costs

This is another important cost concept. All T&D activities have associated opportunity costs, equal to the return on capital that could have been gained from investing in other projects. The concept of opportunity cost is relevant to managers who may wish to consider them before they agree to invest in a T&D programme. In order to calculate detailed opportunity costs of training investments you will require detailed financial information. There is also an opportunity cost to be considered when making a choice between two training options. This cost component is the one least likely to be considered by a training specialist on a day-to-day basis, however it is part of the language of senior management and should therefore be considered as senior management frequently have to make choices about alternative investment options.

UNDERSTANDING THE NATURE OF COSTS

We make a distinction between three different types of costs that are commonly used in accounting terminology:

- Direct Costs: Expenses that can be traced directly to specific projects or activities. In terms of training, out-of-pocket direct costs include: travel, fees, daily expense allowances, costs for purchased learning materials, contracted consultants, training room rental, and food service. Direct costs are the most obvious and easily tracked costs associated with T&D, although out-of-pocket expenses rarely equal more than 10% of a training programme’s total costs. The main cost of training activities relate to people’s time – salary costs for people conducting the training, if it is delivered in-house, or of external consultants, as well as participants’ salaries

- Indirect Costs: Expenses that cannot be directly associated with a specific project or training activity but which are necessary for the organisation to function. Sometimes, the term “overhead” is used to describe all of the indirect costs of conducting training. Examples include costs for interest on organisational debt, general building maintenance and repair, lights, heat, office equipment, and administrative salaries and expenses. Another example of indirect costs is fringe benefits – overhead costs related to the time for which employees are paid but do not work (vacations, sick leave, and holidays) plus employer payments for health insurance, pensions, and other indirect compensation

- Full Costs: The total of direct costs plus indirect costs. Full costs are the best measure of how much it actually costs an organisation to deliver a training programme. In particular, recognition of the full cost of an employee’s time is a key element for understanding the total costs of training programmes.

Benefits

Best practice makes a distinction between two categories of benefits that are relevant in a training and development context: tangible and intangible.

Tangible benefits include:

- Increased Revenue: By impacting the quantity of output or sales per unit of time, training-based improvements can increase revenue. Increased output or sales can be documented and training’s share of the increase can be calculated

- Decreased or Avoided Expenses: A frequent benefit of a training programme is the reduction (saving) or avoidance of costs. By enhancing employees’ skills, training can help improve the quality of a product or service. Other measurements include the reduction of scrap, absenteeism, inaccuracy, grievances, accidents and wasted time or materials.

Intangible benefits are activities, qualities, or conditions that have value but which are extremely difficult, or impossible, to quantify in financial terms. For instance, employee flexibility benefits an organisation, but its contribution is difficult to quantify in cash terms. To keep investment in these benefits in perspective, decision-makers should consider the potential risk of not investing in them and should estimate how substantial intangible benefits might possibly arise.

ESTABLISHING AN ACCOUNTING SYSTEM FOR T&D

We focus in this section on some of the decisions that you need to make when establishing an effective accounting system for training. You will need to consider first what you understand by the term “training and development” for costing purposes, then you will need to determine all of the training cost categories that are relevant. We now explain each of these steps in more detail.

Defining T&D for the Purposes of Costing

Your first step is to reach a decision about what T&D is for the purpose of costing it within your company. We have focused in this book on structured T&D activities with identifiable objectives focusing on knowledge, skills and attitudes and clear learning plans. This definition incorporates the following types of training situations:

- Formal T&D courses offered by the organisation or outside training providers

- Structured on-the-job training conducted by an employee’s immediate supervisor or a qualified trainer and supplemented by written learning objectives and schedules

- Open learning programmes, job rotation assignments, and developmental centre activities– if their primary purpose is enhancing the knowledge and skills of the employee

- Participation in conferences and seminars related to the job or professional area

- A training activity, where an employee learns to use a specialist software package in a learning centre.

The definition of T&D does not include activities such as:

- Meetings and performance appraisals – unless development is their primary purpose

- Self-development that an employee carries out on non-work time or using personal resources

- Meetings of a team of managers to introduce a new product

- A performance review that sets new objectives for the employee.

Determining Your Training Cost Categories

You must identify and define training cost categories to track all of your training costs and to keep your training budget in check. We have already briefly defined training costs into two categories: direct and indirect costs.

CALCULATING T&D COSTS: GUIDELINES FOR PRACTICE

We now explain a number of guidelines that you should follow when calculating training costs. It is important to take into account your organisation’s accounting policies and conventions when calculating the costs of T&D.

Direct Costs: Personnel

There are four categories of direct personnel costs that you may need to calculate:

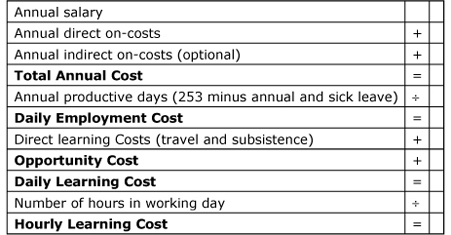

- Training Participant Costs: Estimate the average salary or wage for training participants and include an organisational overhead rate (this will depend on the accounting practices used in your organisation). The Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development (2001) suggests the methodology in Figure 11.1 to calculate the cost of an individual learner’s participation on a training programme.

- Training Personnel Costs: The second direct personnel cost that you will need to calculate is your training personnel costs, which you determine in the same manner as you do your participant costs. If you wish to ascertain the true cost of training personnel, in addition to the time each instructor spends on designing and delivering training programmes, you will also need to factor in the time spent on task analysis, and the identification of training needs, other clerical and administrative support and time spent on training evaluation activities.

- Other In-House Personnel Costs: It is quite common for a training department to use the services of other employees in the organisation to design, deliver or in some way support a training programme or activity. Use the same approach as the previous categories to order to calculate the daily and hourly costs of other in-house personnel who contribute.

- Direct Outside Personnel Costs: These are easy to identify because you usually agree a fee with the external consultant at the point of contracting.

FIGURE 11.1: COSTING AN INDIVIDUAL’S PARTICIPATION ON A TRAINING PROGRAMME

Calculating Cost of Individual Participation

This framework can be used to calculate the cost of the time input for any participants in the learning activity (participants, trainer, administrator, coach, line manager, etc).

Start with the annual salary, including any allowances (skills payments). If a substantial part of someone’s pay is made up of commission or bonuses, include an average figure.

Add employer’s on-costs (PRSI/National Insurance, pensions, and company car). If you want to be extremely rigorous in your calculations, you could also add indirect costs of employment (accommodation, personnel administrative costs, etc). In most organisations, however the information needed to calculate these costs is not readily available, and the effort of attempting to calculate them is probably not justified. An alternative to calculating the exact on-costs of employment is to add on a percentage of salary for on-costs. A reasonable assumption is 35% of salary, although this may vary with seniority and nature of the job (number of “perks”, provision of specialist equipment). Your finance department or accountant may be able to provide a more specific percentage figure for your organisation.

Example of calculation of cost of an individual’s involvement in learning activity:

If you are running a programme of learning activities for a large number of people, calculating the individual cost for each one would be time-consuming. Instead, calculate the cost for the average salary level for each grade represented in the activity.

Whether you use individually-calculated or average figures, you do not need to re-calculate them until, or unless, any of the input figures change (salary increases, changes in travel and subsistence rates, change in venue causing changes in travel and subsistence etc.).

Source: CIPD (2001).

We now explain three other types of direct costs that you will need to factor in when calculating the cost of your training:

- Travel, Accommodation and Incidental Expenses: To establish the total of these costs, multiply the average cost per participant by the total number of participants. Sometimes, it may be difficult to ascertain the average costs of these items of expenditure, simply because training records are not available. Then, you could survey participants in your organisation and find an appropriate average

- Outside Goods and Services: If you use outside goods and services, you will find the total costs for these services simply by adding the sub-costs that make up this category. In some cases, some of these costs are on a per-participant basis, while others are on a per-programme basis

- Facilities: If you have to rent out facilities, then you must include this cost. If the rent is a flat fee – the process is relatively simple; however, if it is not, calculate the total by multiplying the daily or weekly fee by the number of days or weeks of rental.

The CIPD recommends the framework in Figure 11.2 for calculating the direct costs of a training and development activity. This is a very useful matrix because it combines people, accommodation, equipment, material and external costs and considers them for the total training cycle.

FIGURE 11.2: COST CLASSIFICATION MATRIX FOR THE TRAINING CYCLE

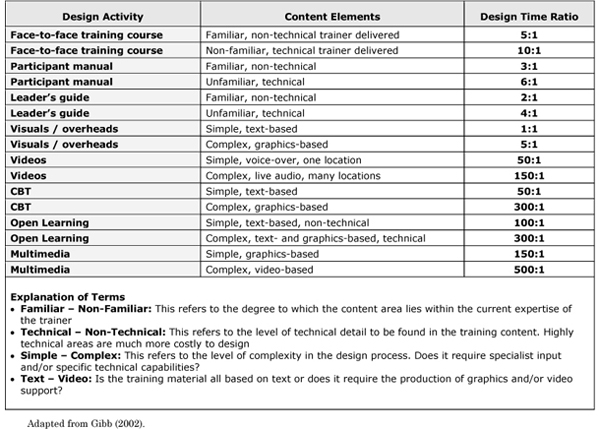

Figure 11.3 outlines a “rule-of-thumb” for calculating the costs for the design of different once-off learning activities.

FIGURE 11.3: DESIGN TIME RATIO FOR DIFFERENT TYPES OF LEARNING ACTIVITIES

Indirect Costs of a Training Activity

Most trainers make systematic attempts to calculate their direct training costs. Indirect training costs can often equal or exceed the direct costs, although they are less likely to be calculated, because they are more problematic to calculate with any degree of precision. The extent and level of accuracy with which you calculate indirect costs will depend on the information available and the accounting policies of the organisation.

There are three sets of indirect costs that you need to consider:

- Overhead Costs: The simplest method you can use to estimate overhead costs are to establish a base percentage rate of indirect costs for all training programmes. If you use this approach, the indirect costs are estimated by multiplying the base percentage indirect cost rate by the training programme’s total direct cost. A more precise method to capture indirect training costs involves the use of total training department budget information

- Facilities Costs: These costs should be accounted for separately from other indirect costs, although they are generally a relatively small percentage of total costs and are often difficult to determine. If your organisation has a well-established accounting function, then it will be easier to ascertain, for example, the costs of electricity, maintenance, building administration and the cost of a mortgage on the premises

- Equipment and Materials Costs: Most of these costs will be incurred in off-the-job training, but they may also arise in other training activities. Some of these costs will include:

- Purchase / subsidy of training material (computer-based training packages or books)

- Payment / subsidy of external course fees (seminar attendance, evening class fees)

- Purchase or hire of audiovisual or computer equipment and materials

- Supply of consumables such as notepads, workbooks, flip-chart pads, etc.

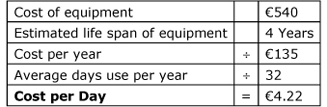

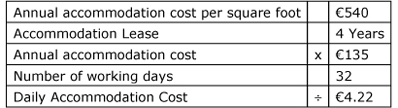

Figure 11.4 outlines the CIPD recommendation for calculating in-house equipment and in-house accommodation costs.

FIGURE 11.4: CALCULATING THE COSTS OF EQUIPMENT & ACCOMMODATION

To calculate the daily costs of using in-house equipment:

- Divide the cost of the equipment by its estimated lifespan

- Divide the annual cost by the average number of days’ use per year to produce the daily rate.

Example of Calculation Cost of Using In-House Equipment

To calculate the cost of in-house accommodation:

- Obtain the figures for annual accommodation cost per square foot (including heating and lighting if possible)

- Multiply square foot cost by the size of the accommodation to give annual cost

- Divide annual cost of accommodation by 253 working days a year (365 minus 112 days for weekends and bank holidays but could be different for an organisation that works shifts) to give accommodation cost per day.

Example of calculation of cost of in-house accommodation

Training Costs: Other Issues

You can make a strong contribution to managing your training department and demonstrate your professionalism to key stakeholders such as senior management if you consider the following training cost issues as part of your overall approach to T&D costs:

- Target Particular Costs: If you target particular cost areas for special scrutiny, this can improve your ability to determine how much should be spent on training and where you can make improvements in the management of training

- Specific Training Populations: You should consider examining training needs and costs for different groups of employees, such as senior management, technical, administrative and clerical / operative staff. If you can get data from other organisations on how much training and expenditure these groups receive, it should help you to identify priority changes and/or confirm that you have your priorities correct

- Subject Matter / Training Needs: It is often a useful exercise to track your training expenditure on different categories of training needs or expenditure on generic courses

- Training Providers: If your organisation uses a number of external training providers, it is useful to track expenditure on once-off providers against regular contributors

- Training Phases: The CIPD recommends that you analyse training costs for each phase of the training process. You may consider the following:

- Costs related to the analysis of needs

- Resources devoted to the selection of training participants

- Design costs related to the choice of learning objectives

- Preparation of training proposal and developing course content

- Development costs related to instructor guides, workbooks, slides, tapes, etc

- Delivery costs related to personnel, outside goods, services and facilities

- Evaluation costs related to training lists, interactions and analyses

- Administrative costs related to scheduling courses, etc

- Research and development costs related to exploring new training approaches

- Marketing costs related to advertising and publishing training, preparing brochures, etc.

Developing T&D Cost Codes

If you are to keep track of training costs, then you will need to develop a cost coding system. This will enable you to keep accurate records. The codes you develop will be determined by the needs of the organisation – and should be agreed with the accounting function before use.

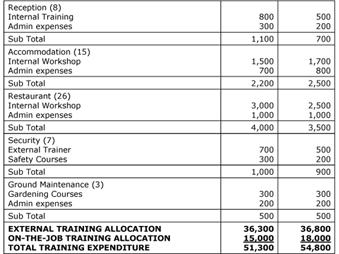

FIGURE 11.5: EXAMPLE OF A T&D BUDGET

Notes on Training Budget

At the time of writing, through CERT Retain, businesses can receive up to €20,000 in training grants. Individual businesses can obtain grant-aid of 50% towards direct training costs for programmes in management development and human resources. We hope to attain approximately €32,000 overall in grant-aid from CERT over two years.

The Training Budgets for 2003 and 2004 are based on 3% of the projected Labour Costs for both years converted to Euros.

General Manager: The General Manager will be sent on an external Hotel Managerial course at a cost of €4,000 per annum. Appropriate CERT courses identified include: Leadership for results, Managing the personnel function, Trainers in Industry

Deputy Manager: One external course at €3,000 per annum. CERT courses as above would also be identified as appropriate to this position

Assistant Managers: An external instructor will be hired to provide training for this group at a cost of €1,000 per annum. CERT courses, as above, have been identified as appropriate with an outlay of €500 and €700 per annum respectively.

Trainee Managers: The six trainee managers will receive internal training from the General Manager and an allocated assistant. All six should be sent on the CERT approved Coaching and Mentoring course. Other appropriate CERT courses identified include: Developing supervisory skills, Leadership for results, Managing the personnel function, Trainers in industry. This would cost approximately €500 per employee.

Rooms / Reception Manager: This employee will receive internal training at a cost of €500 and €600 per year. Appropriate CERT courses identified include: Developing supervisory skills, Leadership for results, Accommodation skills, with an outlay of €500 per annum.

Night Club Manager: This employee will receive internal training at a cost of €500 and €600 per year. Appropriate CERT courses identified include: Developing supervisory skill, Leadership for results, Accommodation skills, with an outlay of €500 and €600 per annum.

Head Barman: The head barman will be placed on a CERT course with an outlay of €800 per annum. Appropriate CERT courses identified include: Introduction to supervision, Leadership for results.

Chief Chef: The chief chef will be placed on a CERT Professional Cookery course with an expense of €1,000 per annum.

Restaurant Supervisors: The two restaurant supervisors will have an external trainer brought in at a cost of €600 per annum. Appropriate CERT courses identified include: Introduction to supervision, Leadership for results, Restaurant advanced skills. We will provide €600 and €800 respectively per annum for the completion of these courses.

Bar Staff: All training will be provided internally. Expenses will be provided to employees who undertake the course.

Kitchen Staff: All training will be provided internally. Expenses will be provided to employees who undertake the course.

Reception Staff: All training will be provided internally. Expenses will be provided to employees who undertake the course.

Accommodation Staff: All training will be provided internally. Expenses will be provided to employees who undertake the course.

Restaurant Staff: All training will be provided internally. Expenses will be provided to employees who undertake the course.

Security Staff and Ground Maintenance Staff: An external trainer will be hired for on-site training.

CALCULATING RETURN ON INVESTMENT IN T&D

The second half of this chapter focuses on some of the issues that you will encounter when evaluating the return on your training investment. Training managers are continually preoccupied by a concern to show that investment in T&D brings tangible benefits to the organisation. They will often resort to methods such as reaction questionnaires, although such questionnaires do not have the capacity to effectively link training activities to financial return. There is evidence of increasing pressures on training specialists to calculate ROI, although the evidence indicates that only a small number of organisations attempt to systematically measure ROI.

We can identify a number of reasons why very few organisations carry out ROI evaluation. Many of them consider it too costly, complex and time-consuming. Seven specific barriers exist:

- Senior management often do not ask for ROI evaluation of training activities. The view often prevails that training, of itself, is a good thing and produces positive outcomes

- Many trainers do not possess the skills to calculate ROI. There is evidence that the collection of ROI data is difficult and time-consuming to collect and analyse

- Training specialists frequently are unsure about what particular dimensions they should evaluate. There is a strong tendency to rely on trainees’ reports of improvements rather than seeking to use appropriate measures that can be quantified

- It is sometimes considered a risky activity to undertake. Trainers believe that they will be blamed, if the benefits do not outweigh the costs

- The attribution of benefits to training is very difficult simply because firm or company performance is influenced by a myriad of factors, including markets, interest rates and the efficiency of technology. This results in imprecise ROI figures for T&D

- The costs of training are generally understood to occur up-front, often before the training activity takes place. It is frequently the case that the benefits accrue slowly over time and, in many cases, depend on unpredictable factors such as turnover rates

- Cultural resistance to measurement of the costs and benefits of training may exist in an organisation. Some senior managers may view ROI initiatives simply as promotion and marketing by the training department. Moreover, the “best practice” companies in terms of training are often the most resistant, and accept the value of training as an act of faith.

We believe that the systematic investigation of ROI will bring a number of benefits to the training function:

- It can help to highlight the value of human resources as a significant element of the productivity growth of a company and as a critical component of the adoption of technology

- ROI analysis can be used as a strategy to bring about continuous improvement in T&D practices. It places a greater emphasis on documentation, measurement and feedback processes

- ROI information can provide T&D specialists with critical information to enable them address poor learning transfer

- Finally, ROI analysis can bring greater accountability and enhanced efficacy to the training function.

Figure 11.6 provides examples of the benefits of a number of training interventions.

FIGURE 11.6: EXAMPLES OF TRAINING BENEFITS FOR DIFFERENT TRAINING ACTIVITIES

Starting the Process: Measuring Costs and Benefits

In order to conduct even the most basic analysis of ROI, you will need to ascertain a reliable estimate of costs and benefits.

Return on investment can be used to examine a single isolated training intervention to assess its potential. It has three basic inputs:

- The life or time of a training project

- The amount of investment

- The cash flow after expenses.

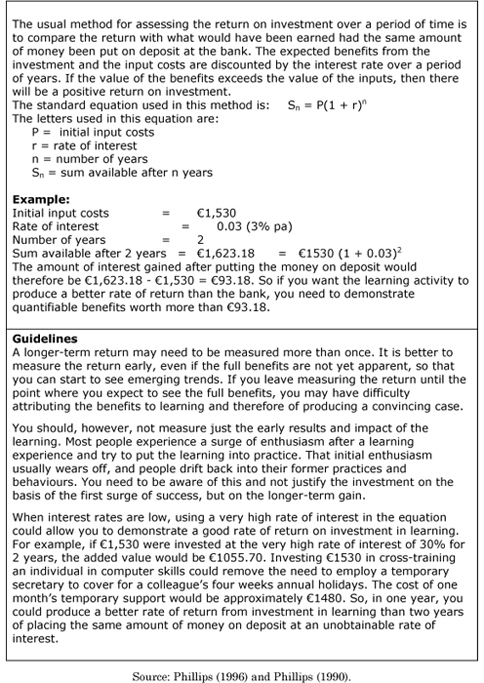

We now look at three models that you can use:

- Compact Cost-Benefit Analysis: This method measures job performance after training. It is a “compact method”, because it uses a formula, not a spreadsheet, to calculate ROI. The result is a monetary amount that describes what the training is worth to the organisation in terms of the performance of employees who have participated in the training. Five steps are calculated to determine the benefits of training using this method:

- Determine the effect of the training

- Determine the monetary value of the effect

- Find out how many people have been trained

- Determine the training cost per person

- Put the information together in the formula and calculate.

Figure 11.7 presents an example of compact cost benefit analysis.

FIGURE 11.7: CALCULATING THE RATE OF RETURN ON T&D INVESTMENT

This compact method has a number of advantages and disadvantages. The advantages are:

- It uses a monetary unit of measure for the analysis. This unit of measurement is usually acceptable to managers because they understand it

- The method is relatively simple to use

- It does not require extensive computer capability or number-crunching power

- It provides results fairly quickly (you don’t have to wait for a one-year budget report).

However, it is problematic because:

- It relies on the reports of supervisors and managers concerning the benefits. These reports may not be reliable

- It assumes that the correct training solution was applied in the first instance

- Long-term benefits many not be directly attributable to the training

- It is necessary to make certain assumptions about interest rates and the number of years over which the benefit will accrue

- The Relative-Aggregate Scores Approach: This approach compares the relative value of training for different tasks or duties within a job, and for assessing the gain in value for that job after training. When you use it to assess the benefits of training, the difficulty, importance and frequency of various job tasks needs to be assessed. For each of these elements, weights need to be derived. Then, actual performance data are used to show a value for each task, a performance value before and after training, and a performance gain for each task, as well as for the job as a whole. The results of this approach can be used to monitor the results of training and also to plan training so limited resources are invested in the most important or priority areas

- The Maurice Model: This model is a combination of numerous ROI models. It consists of the following six steps:

Estimated figures:

- Step 1: Calculate the potential for improved performance. A front-end analysis is conducted to determine the purpose of the training request, identify the desired and actual performance after training, and identify the appropriate solutions that are relevant, feasible, and acceptable to the organisation and the targeted employees

- Step 2: Calculate the estimated training costs. These costs include development costs, implementation costs, and maintenance costs

- Step 3: Calculate the value analysis. This step verifies the value of training by comparing the cost of training to potential outcomes. First, estimate the highest number and the lowest number of annual deficiencies or improvements. Second, estimate the high and low cost of each deficiency or improvement. Third, calculate the current annual cost of both the high and low deficiencies or improvements. Fourth, estimate the range of expected deficiencies, corrections or improvements obtained from training. Fifth, estimate the high and low annual value of training. Sixth, multiply the high and low annual amounts of training by the length of time the training will last and divide the estimated training costs to obtain the potential worth of a training intervention

Actual figures:

- Step 4: This step includes design, development, implementation, support, and monitoring/evaluation of training and refers to the actual implementation of the training and the measuring of costs

- Step 5: Calculate the true costs of training. This step is similar to step 2, but now actual figures are used in place of estimated values

- Step 6: Calculate the organisational ROI. This step involves estimating the percentage of impact likely due from training and calculating the value of results against training costs. This should be done only on projects where training has been the major performance improvement intervention.

The first three steps are a front-end analysis, based on estimated rather than actual costs; the latter steps are based on actual costs.

SOME ISSUES WHEN PREPARING A COST/BENEFIT ANALYSIS

There are a number of practical decisions you must make in order to conduct an effective ROI analysis.

The Basic Procedure

The basic sequence or approach for calculating a monetary value for any learning benefit, whether hard or soft is as follows:

- Identify one unit of data – for example, one error, one employee grievance, one customer complaint

- Put a monetary value or cost on each unit. Ask people in the line or personnel to help calculate the value, if the management information is not available

- Calculate the change in performance pre- and post-learning

- Calculate the change in performance over a comparable period. Make allowances for any other factors that may have affected performance – for example, reduced equipment breakdowns might be partly due to a new servicing routine

- Calculate the annual change in performance. The most valid way to do this would be to wait till the end of the year, but if you need to produce data sooner, then you could compare shorter periods and extrapolate for annual performance (but beware of any seasonal trends, for instance, does the error rate go up in summer when numbers of casual staff are taken on?)

- Calculate the annual value by multiplying the annual performance change by the unit value. If you subtract the cost of the learning from this figure, it will give you the annual return on investment.

Considering Benefits

When you are considering the benefits of your training, the following may be relevant:

- Output, wastage and sales, which are expressed by value, or by units or amounts, which can be readily converted into monetary value

- There are several indicators of improved quality that can be quantified to produce monetary values, including:

- Error rates: The cost of errors include any materials wasted and time spent correcting the error. There may also be an additional cost of dealing with any resultant customer complaints

- Customer complaints: The costs of customer complaints includes time spent investigating and remedying the cause of the complaint. Some organisations also add in the cost of “shadow” complaints, estimating that for every customer who complains there are others who vote with their feet

- Customer satisfaction ratings: One unit could be represented by a 5% increase in customer satisfaction ratings; if your organisation conducts a customer satisfaction survey, then it should be possible to identify the value to the organisation of an improvement in rating

- You can express employee performance, commitment and morale in terms of the following units:

- Productivity

- Attendance: The cost of one day’s absenteeism will be the cost of a productive day’s salary (see calculations for individual participation in learning)

- Staff turnover: If your organisation has a personnel department, they should be able to tell you the average cost of recruitment. Calculation of the cost of staff turnover should also include the value of lost output whilst a job is vacant and the reduced output while the new recruit learns the job.

- Equipment breakdown: If people do not have the correct skills and knowledge to operate the equipment they use at work, there are likely to be more breakdowns. The cost of an average breakdown can be calculated in terms of lost production, time taken to repair the equipment and any spare parts needed

- Health and safety incidents: The cost of a health and safety incident includes lost time and possible sick leave of the employee(s) involved, management time in investigating the incident, and possible management time and legal costs in a resultant court case

- Formal grievances: The cost of dealing with a grievance includes lost employee and management time in the line and human resource department.

Other Issues

Other issues that you will need to consider when preparing a cost-benefit analysis include the following:

- You will need to decide over what period you will expect to see full payback from your training investment. This will vary according to the nature and objectives of the learning or training activity. Full payback on an apprenticeship, for example, will take four to eight years, and even after payback is achieved, the benefits of learning may last a lifetime. For sales training on a new product line, payback will be expected much sooner, and the learning may have little or no value after the product line is withdrawn or is modified

- If you find it difficult to calculate a financial value for the organisational benefits, you should ask managers to put their own value on the benefit – but, if you do this, err on the side of caution for the sake of credibility

- You should proceed from the position that not every benefit from learning can be quantified in monetary terms, so do not ignore pay-forward benefits, which we briefly discussed in Chapter Two. Qualitative pay-forward benefits are particularly apparent and applicable in organisations that are implementing a programme of change, which includes elements of cultural change. Change programmes include a number of initiatives and it will never be possible to attribute exactly what benefits arose directly from learning activities and what role other factors played in bringing about the changes. Moreover, the aim of change is often to shift perceptions and attitudes rather than develop skills and knowledge; thus to attempt to apply quantitative measures to qualitative benefits is unrealistic and artificial. In such circumstances, you should direct your efforts to identifying pay-forward qualitative benefits such as:

- Improved team-working and co-operation

- Increased understanding and awareness of the organisation’s purpose and objectives

- Better identification of and focus on strategic priorities

- Development of and/or adaptation of a new organisational culture.

TECHNIQUES & STRATEGIES USED TO QUANTIFY THE BENEFITS OF T&D

The management and training literature is replete with examples of strategies and techniques you can use to quantify the benefits of training and development. Some of them will give you a rough and more subjective measure, others are more precise but may be complicated for you to use. We will consider some of these approaches and techniques and comment on their strengths and weaknesses.

Direct Reports from Participants and Line Managers

You could ask participants and line managers to provide estimates of what improvements have occurred in their performance and how much of this can be attributed to a training and learning activity. This approach has advantages in that it solicits direct feedback from those directly involved in implementing the results of the activity in the workplace. It represents an attempt to quantify a level of improvement in both hard and soft skills.

However, direct reports suffer from two significant limitations: the estimates of benefits derived are subjective and they are likely to vary considerably; and any quantitative data, which you derive from the process, will be at best an estimate.

You could enhance this approach by using a combination of structured interviews and questionnaires. The greater the number of people who contribute estimates, the less likely it is that eccentric responses at the extremes will distort your data and the more confident you will be concerning your findings.

TABLE 11.8: USING DIRECT REPORT EVIDENCE: STRATEGY & EXAMPLE

Strategy |

Example |

In order to elicit the appropriate information, you will need to ask the following questions:

The question about people’s level of confidence about their estimate is key, as it allows you to get a more rounded picture of the possible impact of the learning and to show that you are taking a cautious approach to handling subjective information. The response to the confidence question should be factored into the response about the percentage improvement attributable to learning. |

Participants estimate that their performance has improved by 25% (one box marking on a five-box appraisal scale; output up by 25%; error rate reduced by 25% etc) |

360° / 180° / 540° Feedback

This method consists of asking those working with participants to assess the participant’s behaviour against certain observable criteria. The questionnaires can be sent to peers, boss and subordinates (360°), peer and subordinates (180°), peers, subordinates, boss and other contacts such as customers (540°).

This approach has a number of advantages in the context gathering information about benefits. It is particularly useful when you are attempting to evaluate the impact of learning activities directed at improving less easily-evaluated skills such as leadership, management of others, communication and customer service. It allows direct report input for management and leadership skills. It is anonymous, so the feedback is more likely to be objective and it is very useful as a “before” and “after” measure. You could also use it to measure learning over time.

Qualifications Obtained

Qualifications are evidence of achievement, but not all qualifications will be directly related to an individual’s current job, nor are they in themselves a guarantee that the individual will apply the certificated skills and knowledge on the job. The types of qualifications that best reflect the impact of learning on performance in the workplace are those qualifications that are assessed on a competency basis in the workplace. Such qualifications can be awarded only when an individual can demonstrate the ability to transfer and apply learning on the job.

Appraisal / Performance Management Reports

If your organisation has a performance management system, this might provide valuable sources of data to enable you to assess the impact of training. The main advantage of this method is that the data already exists and does not have to be specially collected.

It does, however, have a number of inherent weaknesses. Learners may be concerned about the confidentiality of their ratings. It is also a problematic technique in terms of identifying and linking changes in performance to specific learning or training activities. It is possible that the skills and knowledge that are assessed during the performance review process are not the same as the skills and knowledge that the learning activity sought to develop.

This approach will be more effective if your organisation has conducted a learning activity directed at improving the performance of a team or a particular occupational group.

Structured Interview with Senior Managers

This is a similar process as with participants and managers, but repeated at a more senior level in the organisation. It asks managers to focus on the broader picture and the impact on the organisation rather than on individual performance. Its primary strength is that it involves senior management in the evaluation process and, therefore, in the decision-making process concerning T&D.

It has two main disadvantages:

- It requires a significant amount of senior management time

- It may be difficult to get senior managers to engage in the process.

Also, in some organisations, especially larger organisations, senior management may be too far removed from the workplace to observe the direct impact of the T&D intervention.

FIGURE 11.9: USING SENIOR MANAGEMENT EVIDENCE: STRATEGY

Identify which members of the senior management team are most likely to have observed the impact of the training and development activity.

Ask questions that concentrate on business – not learning – objectives and measures: for example, “‘What changes in output/customer service have you observed?”. Top managers’ interest is not focused on whether people are better skilled, but whether their performance is adding value to the organisation’s overall performance.

You could consider combining the structured interview with the senior managers’ evaluation of benefits.

The definition of “senior management” will vary depending on the size and structure of your organisation. In a company employing less than 100 people, it is likely to be director level. In a large company employing 5,000 people, it is more likely to be the level below director.

Send the interviewee a list of the main questions you want to cover, in advance. This will reduce the time needed for the interview and allow for a more considered response.

The level at which you interview will also depend on the depth and breadth of your training and development programme. For instance, if in a large organisation you have targeted only first line managers, then a Board member is unlikely to be able to identify the specific impact of the training and development activity. However, if the learning activity involved every member of staff, then you could expect Board members to be aware of the activity and its impact.

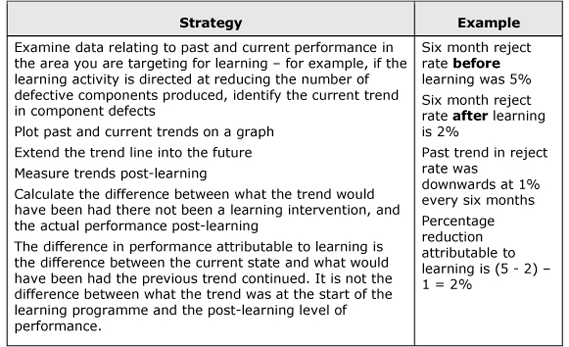

Trend Line Analysis

This process involves studying current trends in organisational performance, projecting them into the future and then assessing the impact of learning on those trends. It has two major advantages:

- It possesses the potential to demonstrate a clear link to critical aspects of organisational performance

- It uses existing data.

However, the process assumes that all other factors remain the same.

Impact Analysis

Impact analysis involves representatives of all stakeholder groups likely to be affected by the learning activity in a workshop before the learning activity. It has a number of advantages in that it ensures the involvement of all key stakeholders. It is useful in identifying learning objectives and predicted areas of impact for follow-up evaluation. It helps build stakeholder commitment to the learning activity and it achieves stakeholder consensus on learning objectives. It does however demand a lot of time from each stakeholder.

FIGURE 11.10: TREND LINE ANALYSIS: STRATEGY & EXAMPLE

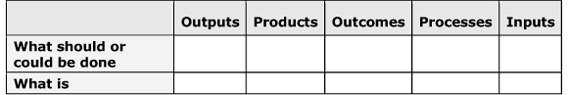

The Organisational Elements Model

The Organisational Elements Model (OEM) is designed to demonstrate the relationship between organisational efforts, organisational results, and external payoffs. The aim is to demonstrate the relationship between inputs and results.

The key point of this analysis is the need to show linkages between all the elements of the process, from inputs through to outcomes. If the chain breaks at any point, this indicates there is no connection between the elements – for example, learning inputs are not contributing to the creation of outputs, and therefore there is no return on investment.

It is considered very useful in identifying areas where evidence of post-learning benefits may be found. It is also useful as a diagnostic tool to identify where there may be a learning need.

It has two major disadvantages:

- It provides no hard data

- It can appear academic.

As a consequence, it is possibly more useful as an aid to discussion rather than persuasion.

FIGURE 11.11: IMPACT ANALYSIS: STEPS

Before the design stage, organise a half-day workshop comprising:

- Agents: People who produce, use or implement the learning activity

- Beneficiaries: People who will benefit from the activity in some way – for example, participants, their line managers

- Victims: Those who will be negatively affected – for example, colleagues who have to cover for people on day release.

Some people may fall into more than one category, for instance, a line manager could be a beneficiary in the long-term, but a victim in the short-term.

Ask each stakeholder to write down what he or she considers the three most important purposes of the learning activity, one purpose to a piece of paper.

Collect the statements and print them up on a board/fix them on a wall.

In discussion, group the purposes into related clusters and agree a title for each cluster.

Give each stakeholder 10 points to allocate as he/she chooses between the clusters, with the most points to the cluster he/she thinks represents the most important learning objective. There are no restrictions on points allocation; stakeholders can give all the points to one cluster if they wish.

This process should have identified the overall learning priorities for all the stakeholders.

Ask the group to consider each of the learning objectives in turn, and to suggest how they would assess whether or not the objective had been achieved and evaluate its impact on the organisational performance.

Guidelines:

It is most useful in setting up a larger and/or expensive learning programme that is likely to have a major organisational impact.

The clustering process works well using large size “post-it” notes on a wall or flip-chart paper.

You can add in an extra stage between prioritising objectives and identifying evaluation measures, which would be to carry out a force field analysis of factors that will help or hinder the learning activity and process. If you do this, you will need more than a half-day workshop.

You may choose to reconvene the workshop after the learning activity (or perhaps when it is well under way, in a long programme) to see if stakeholders’ priorities have changed and if the impact and evaluation measures are proving valid.

FIGURE 11.12: ORGANISATIONAL ELEMENTS MODEL: AN APPROACH

Identify the following elements involved in the learning activity:

- Inputs: numbers and types of participants; organisational resources; policies

- Processes: learning methods; flow of participants etc

- Products: completion of learning activities; tests passed etc;

- Outputs: application of the learning

- Outcomes: longer term and broader payoffs, such as self-confidence and motivation.

- Write this information in the boxes in the OEM table, with the top row showing what your organisation would like the situation to be, and the second row showing the reality of the current situation.

Look at each of the elements and see whether there is a clear link between it and its neighbours. For instance, are inputs used in processes, are outputs the result of the use of inputs in processes?

Missing elements or a lack of clear linkage between elements indicates “disconnects” - areas where there are inefficiencies or lack of the necessary resources and methods to deliver useful results.

An effective learning activity will show clear links between products and outputs and outcomes.

Control Groups and Pilots

This process involves comparing the performance of a group who have undertaken a learning activity, with another group, who have not (the control group). Any improved performance in the learning group demonstrates the impact of the learning. When a pilot project is run, those not taking part in the pilot can in effect be used as a control group.

This approach has two major advantages:

- It helps disentangle the impact of learning from the impact of other factors (for example, new equipment)

- It is a useful tool to demonstrate the benefits of learning to a wider sceptical audience.

It is problematic in that it is impossible to exclude effects of other actors; even the fact that people are being observed has been shown to affect their performance (the Hawthorne effect) and it is very difficult to get pilot and control groups that match in terms of composition, experience, etc.

There are a number of issues you need to consider when running a pilot or using a control group:

- If you are running a pilot, and using the rest of the population as a control group and do not tell them in advance that they are the control, then you can prevent the Hawthorne effect. However, this means you will not be able to carry out any pre-learning measures on the control group that require the control group’s involvement/knowledge.

- The assessment of performance is of the group as a whole; merely recording that each individual’s performance has improved means relatively little

- Use any combination of evaluation tools to evaluate the impact of the learning on the group’s overall performance. For instance, compare output and error rates, absenteeism, health and safety incidents, etc. Ask the senior managers responsible for each group to evaluate the group’s contribution to organisational success before and after the learning activity

- You should choose as a pilot group a group whose members are positive toward the idea of learning, but are also as representative as possible of the target population.

PUBLICISING THE RESULTS & MARKETING THE BENEFITS OF T&D

If you conduct a cost-benefit analysis, it is important that you use it to put together a strong case for investing in T&D in the future. You will need to think about your presentation and strategy, as much as about the content of the arguments you make when you communicate your findings to stakeholders.

Presentation Issues

It is important that you consider the following:

- What is the usual style of presentation in your organisation? For example, written report with several appendices, short graphical illustration, executive summary with appendices, or oral presentations?

- Do you want to use the usual presentation style or increase impact by doing something different? What would be the risk of a change of style?

- Look at your terminology: Talk about “investment” not “cost”

- Concentrate your efforts on the activities that will have the greatest organisational impact. Mayer and Pipe put learning activities into three categories: “shoulda”, “oughta”, “wanna”:

- “Shoulda” are activities that the organisation must undertake, either because of legislation (health and safety procedures) or because they are basic to performance of the job (teaching keyboard users to type)

- “Oughta” activities are those that there is general agreement are likely to benefit an organisation (management skills, updating professional expertise)

- “Wanna” activities are those where the benefits are less obvious or are apparent in the longer term (stress management, creativity)

- Make sure your calculations of the up-front investment and expected return on investment are realistic. Where you have had to estimate, say so, and explain the grounds for your estimates. Finally, double-check your figures to make sure the calculations are correct.

Responding to Negative Perceptions about T&D

You need to consider the negative arguments you are likely to come up against in your organisation. Examples include the following:

- “We place no value on training in our organisation.”

- “Training stops production and production must never be stopped.”

The CIPD makes the following suggestions for pre-empting or countering each of these arguments:

A failure to see the hidden cost of learning by trial and error:

- Cite examples of where mistakes have been made because people were inadequately trained or were thrown in at the deep end

- Identify current mistakes / under-performance and quantify what they are costing your organisation, as well as the value of even a small percentage improvement in individual performance

- Evaluate and compare the performance of a trained or pilot group with an untrained control group.

A belief that effective performance results from innate ability not learning (managers are born not made)

- Quoting individual experience can be powerful in this situation. Find someone who is willing to talk about how they were able to improve their performance following a learning activity. If you are dealing with management skills, get someone’s staff to describe the impact of learning on their manager’s performance

- Again, evaluating and comparing the performance of control and pilot groups can provide useful evidence.

A lack of an explicit causal link between learning and effective job performance

- The Hamblin model level three (measuring the impact on individual performance), which we explore in the next chapter (this evaluation tool will provide the evidence needed to counter this argument).

An inability to distinguish between the effects of training and other factors

- Disentangling the impact of learning from the impact of other factors can be difficult, especially if you are dealing with a situation where there are a number of initiatives taking place at once (reorganisation, new equipment or processes being introduced). A rigorous evaluation process is crucial, involving internal control group comparisons where possible, or external benchmarking comparisons

- Data on personal beliefs and attitudes about the relearning may also be effective. In a time of change, maintenance of staff morale is both critical and difficult. Learning often helps by giving people the tools and information to handle the change. A questionnaire and/or programme of interviews will provide information on whether or not people believe the learning is helping them.

A belief that trained staff will be poached and that others will reap the benefits of investment

- Benchmarking research can help in countering this argument; you should look at organisations that have a high reputation for investing in the development of their people and see if you can obtain any information about their staff turnover

- Look at the staff turnover figures for your organisation: Is there a positive or negative correlation between investment in training and staff turnover? Or no obvious correlation?

- Most staff interpret the organisation’s willingness to invest in their personal development as a signal of the organisation’s loyalty to them, and respond positively; consider conducting an attitude survey by questionnaire and/or interviews in your organisation to obtain staff views about your organisation’s investment in learning.

The view that, as long as an individual is performing competently in a current job, the organisation does not need to invest any more in training and development

- This view represents a failure to see the added value benefits of investing in learning; the fact that “with every pair of hands, a brain comes free”. Look for individual examples of people who have benefited from learning to advance their careers from an unpromising start to build a case for showing how the organisation is under-utilising its human resources

- Look for spin-off benefits from learning, such as staff suggestions for improvements.

Previous poorly targeted or delivered training

- Examine past learning failures, talk to those who were directly involved and identify why it didn’t work. Was the initial business issue correctly identified? Was learning the answer, or was some other action needed? Did the training or learning activity have clearly specified objectives and was it linked directly to the business objectives? Was the nature of the activity appropriate to the organisation’s style and culture? Demonstrate why the pervious activity failed to produce the hoped-for results, and show how you will avoid repeating the same mistakes

- Spend time and effort at the front end of the process of linking learning to organisational success, so that you can be confident learning activities are correctly targeted and appropriately designed.

As well as preparing to counter negative arguments, you need to consider how to put together the case for investment, including:

- Identifying both current mistakes and areas of under-performance that are costing the organisation

- Thinking both laterally and longer-term about intangible outcomes and pay-forward issues.

Strategy for the Presentation of Your Findings

The following are the issues that you need to consider:

- Think about whom you have to convince - usually senior management

- Whenever possible, speak to the people who need to be persuaded on an informal 1:1 basis before any formal decision-making process. Identify for each of the individuals involved what their position will be (agent, beneficiary or victim). Demonstrate that you have thought about and understand their position. Identify the benefits to them as individuals and their group; for victims, this may be the long-term overall value to the organisation. Try and think of some parallels – the problems everyone had bedding-in new IT system, but the benefits it brought in the end

- Is there anyone who would act as a champion in making the case for investment in learning? Your case will be strengthened if you can win the support from people in the line or senior management who are seen as having no axe to grind; best of all, can you win over the Finance Director or budget-holders to support investment in learning? It would also help your case if you can convert an individual who was previously known to be sceptical about the value of investment in learning to the view that learning pays

- Will you have to make your case as a formal presentation, in an informal meeting or in writing? You may want to practise a formal presentation

- What arguments will appeal most to your organization and its managers? Do they want to be seen as on the cutting edge? Are they concerned to stay in step with competitors/parallel organisations?

- Don’t neglect the marketing of the benefits during and after the learning activity. Keep everyone informed about progress and publicise success and results of the early evaluation stages. If things aren’t going as well as expected, don’t try and hide this: publicise your strategy for dealing with it

- Look for opportunities to get wider publicity and recognition for your successes; a write-up in the local press about learners’ successes, consider national award schemes – for example, Investors in People, National Training Awards, Excellence Through People – or articles in trade or specialist press about your activities. If you have one, liaise with your marketing or publicity department over promotional opportunities.

BEST PRACTICE INDICATORS

Some of the best practice issues that you should consider related to the contents of this chapter are:

- A specific proportion of revenue is set aside annually, adequate to resource all planned training and learning activity in the organisation at corporate, unit and operational levels. There is a clear rationale for this proportion, and it is well communicated across the organisation

- An appropriate proportion of the T&D financial investment is targeted on training initiatives and other learning activities that will enhance and continuously improve performance in the workplace

- The T&D budget is not one of the first to be cut in any cost-reduction plan or other contingency. It is treated in the same way as the budgets of other functions and processes that are core to the business

- Top management assesses the added value, as well as the cost, of T&D activity at least annually

- When you are measuring the benefits of training, know your audience and ensure that measures of training impact provide the evidence that is most persuasive, based on their information preferences and priorities

- Distinguish between organisational results and the financial impact of those results. You should measure the outcomes that make the most sense given the strategic priorities of your organisation.