Nowadays we tend to think of Richard Wagner as an opera composer whose ambitions and versatility extended beyond those of most musicians. From the beginning of his career he assumed the role of his own librettist, and he gradually expanded his sphere of involvement to include virtually all aspects of bringing an opera to the stage. If we focus our attention on the detailed dramatic scenarios he created as the bases for his stage works, we might well consider Wagner as a librettist whose ambitions extended rather unusually to the area of composition. In this light, Wagner could be considered alongside other theater poets who paid close attention to production matters, and often musical issues as well.1 The work of one such figure, Eugène Scribe, formed the foundation of grand opera as it flourished in Paris in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Wagner arrived in this operatic epicenter in the fall of 1839 with work on his grand opera Rienzi already under way, but his prospects at the Opéra soon waned. The following spring, Wagner sent Scribe a dramatic scenario for a shorter work hoping that the efforts of this famous librettist would help pave his way to success. Scribe did not oblige. Wagner eventually sold the scenario to the Opéra, but not before transforming it into a markedly imaginative libretto for his own use.2 Wagner’s experience of operatic stage production in Paris is reflected in many aspects of the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer, the beginning of an artistic vision that would draw him increasingly deeper into the world of stage direction and production.

The two and a half years that Wagner spent in Paris from September 1839 to April 1842 were full of eye- and ear-opening opportunities, despite the many challenges he encountered. From his post as musical director in Riga and work as conductor in a handful of provincial German houses, he had gained in-depth experience with a cross-section of repertoire, including Auber’s influential early grand opera La muette de Portici. What he could have only gleaned up until this stage, however, was the extraordinary level of resources that supported opera production in the French capital, together with the intricate production system that was inherent to grand opera. An 1836 performance of Gaspare Spontini’s Fernand Cortez in Berlin had made a strong impression on him on account of its overall integrity and level of professionalism—Spontini oversaw the production. In Paris, the growing complexities of grand opera and opéra comique, with their large moving choruses and elaborate production-specific designs and technical effects, went hand in hand with a process that supported and coordinated the efforts of many specialists. The results were carefully documented so that productions in Paris could serve as models for other performances, the concept of the work now also extending to its realization onstage.3 The seeds of Wagner’s far-reaching and idealistic view of what could be achieved technically in opera took firm root in these years. Cutting-edge technology and high-level illusions were featured above all in popular forms of theater, offering a spectrum of possibilities that fueled Wagner’s imagination, especially as he developed the two works that he would produce toward the end of his life in his own theater in Bayreuth: Der Ring des Nibelungen and Parsifal.4

Although Wagner left Paris deeply ambivalent about the operas that thrived there, he soon lamented the means and method of opera production in Paris compared with what he returned to find in Germany, not least the lack of a healthy-size violin section in Dresden as he began rehearsing Rienzi: “I sensed a certain poverty in German theatrical efforts, most evident when operas from the Parisian repertory were given…. Although I had already felt profound dissatisfaction with this kind of opera during my Paris days, the feelings that had formerly driven me from the German theaters to Paris now came back to me.”5 The ultimately successful premiere of Rienzi on October 20, 1842, enabled the premiere of the riskier Der fliegende Holländer the following January. Although on a more modest scale, Der fliegende Holländer is nevertheless ambitious scenically, involving as it does a regular and a ghostly ship in the framing acts and a closing scene in which the Dutchman and Senta are to be seen rising out of the waves. This final tableau did not feature in Wagner’s prose sketches for the opera but emerged as a stage direction in the first version of the full libretto, completed on May 28, 1841.6 The evolution of this ending takes us to a core of issues that engrossed Wagner as he began to develop the innovative ideas that would lead to the “music drama,” including new ideas about acting and stagecraft.

As initially envisioned in prose, Senta leapt into the waves at the end of the opera and disappeared along with the Dutchman and his ship. It is a tragic close, ringing with irony as the Dutchman sets off without recognizing that Senta is the extraordinarily faithful woman he has been seeking to redeem him from his cursed existence. She proves true to her oath of fidelity until death in an extreme fashion. In developing his prose material into a libretto Wagner placed additional value on Senta’s angelic nature and on her role as redeemer, both ultimately manifested in the final image of her ascent with the Dutchman.7 In the weeks prior to July 11, 1841, when he began working on the continuous composition sketch, Wagner further developed Senta’s character through the addition of stage directions connected to new compositional options. In this phase, his handling of Senta’s Act 2 Ballad unlocked the potential of the opera’s final tableau, moving beyond tragedy to a celebration of the extraordinary psychological nature of Senta, which first enabled her to commit to being his redemptress.

“Senta’s Ballad” is one of several stage songs performed within the opera, none of which unfolds as a discrete musical-dramatic unit; each is broken off, interrupted, and resumed in accordance with varying dramatic contexts. In Act 1, for example, the Steersman’s song, anticipating reunion with his sweetheart, breaks off as he is overcome by weariness. When he reawakens many minutes later he resumes singing his song after a substantial contrasting musical-dramatic unit has unfolded—the Dutchman’s arrival and monologue. Such strategies are typical of the more realistically shaped and extended musical-dramatic units of grand opera and other repertoire that Wagner knew. Related here, too, is Wagner’s practice of composing gesturally or mimetically significant music, whereby stage action and musical gestures are interconnected.8 More remarkable still is Wagner’s recourse to psychological nuances of the dramatic scenario to shape and correlate text, music, gesture, and stagecraft. Each of the opera’s acts features a stage song that is sung by characters who are at work (the Steersman sings while on watch) and/or who are doing something physical that dovetails with material in which the legendary and supernatural emerge with substantial expressive power. But the eerie and the uncanny is ultimately only a way station. Each time, mundane realism opens out toward a formal and psychological complexity that outstrips the ways the supernatural functions in the Schauerromantik style of Marschner’s Der Vampyr, for example. The juxtaposition and intermingling of a conventional but finely wrought kind of musical-dramatic realism with a more psychologically driven form is a characteristic of all of Wagner’s mature stage works. He unstintingly demanded that things incredible to our rational minds should be acted, designed, and carried out onstage persuasively, expanding the aesthetic horizon.

Against the melodically winsome but mechanical “Spinning Song” of the women’s chorus, Senta offers her rendering of the Ballad in a song contest of sorts. Within the Ballad’s basic strophic framework of three verses, the description of the legendary Dutchman’s terrible plight is contrasted with a refrain questioning the possibility of his redemption. As an advance promotional excerpt written before he had fleshed out the libretto, Wagner’s first version of this text ended after the third refrain but did not include Senta’s subsequent bold claim to be the Dutchman’s redemptress. Weaving the song into the libretto Wagner added stage directions that yielded not merely a solo performance but a more dynamic and interactive one, with the onstage audience of women sympathetically participating in the close of the second refrain. Senta becomes increasingly involved with her performance until, after the third and final refrain and “suddenly carried away in exaltation” (“von plötzlicher Begeisterung hingerissen”), she claims to be the redeeming woman the Dutchman seeks.9 It is not clear whether at this stage Wagner foresaw this text having any musical relationship to the setting of the Ballad proper. However, shortly before he began composing, he added another stage direction before the third refrain: “Senta pauses, exhausted, while the girls continue to sing quietly.”10 While Senta is outwardly disengaged from the performance, the chorus takes over and quietly sings the final refrain’s crucial questions: “Ah, where is she, who can point you to the angel of God? / Where might you find her, she who will remain true to you even unto death?”11 Senta is reenergized at this point, as per the earlier stage direction, but her offer to save the Dutchman represents both an answer to the questions of the other women as well as her displaced offering of the final refrain in a radically reinterpreted form. In Wagner’s musical realization of the Ballad, it is as if Senta is able to command the orchestra to assist in the dramatic rendering of her part; the orchestra collapses into silence with her while the song continues, realistically, with the other women singing a capella. Senta’s reengagement and vocal reentry brings the orchestra back into play with a transformation of the refrain’s originally gentle woodwind melody and sympathetic questioning tone, extending the framework of the Ballad just as she claims the role of the redeeming woman in an assertive coda. In this process, Wagner found a way to develop material within the Ballad that could come into play in later parts of the drama to underscore not simply Senta’s uncommon sympathy for the Dutchman but also her uncommon willingness to be his redemptress or, in more general terms, her exceptional transformational powers. At the same time, Senta became a more psychologically unusual character, demanding more of a singing actress than if Wagner had pursued a simpler teleological path in her performance of the Ballad.

Wagner did not suddenly change Senta’s nature. Instead, he sharpened its profile as he aligned it with other parts of the libretto in which she behaves extraordinarily. Later in Act 2, Erik shares with Senta his dream in which he has seen the arrival of the Dutchman. The dialogue with Senta in which he describes this dream triggers her to repeat her assertion to be the Dutchman’s redemptress. In his last round of revisions to the libretto before he began composing, Wagner inserted the performance direction “in a muffled voice” (“mit gedämpfter Stimme”) so that again Senta’s striking response is to material delivered in an understated, hushed manner. As composed, Erik’s dream narration is arguably one of the most innovative passages in the score, its more nebulous shape emulating both the narrative’s origins in a dream state as well as the process whereby Senta gradually becomes confirmed in her resolution, and hence motivated to reclaim the confident coda with which she had concluded the Ballad. For the published piano reduction, Wagner expanded the stage direction at the onset of Erik’s narration to read: “Senta falls exhausted into the chair; at the onset of Erik’s narration she sinks as if into a magnetic sleep, so that it seems as if she dreams the dream that is told to her.”12 In clarifying the state Senta is in as she hears Erik’s dream and his questions, Wagner drew further attention to the connection with her performance of the Ballad. The reference here to “magnetic sleep” points to the concept of animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism or artificial somnambulism, a stepping-stone in the development of hypnosis and the source of much fascination as well as skepticism.13 In both cases, Senta passes into a state in which she does not seem to be outwardly conscious, while significant material concerning the Dutchman unfolds and serves as a link to her audacious proclamations.

What is pertinent here is that Wagner explicitly identifies a psychological model that served as a primary creative stimulus in his shaping of Senta’s character, her manner of performance, and the experimental musical processes that prepare and illuminate her role as the Dutchman’s redemptress. Somnambulism was a popular theme on Parisian stages in the late 1820s, spilling over into French literature through the 1840s.14 Scribe’s own work in this vein includes the libretto for Ferdinand Hérold’s 1827 ballet-pantomime La somnambule, the precursor to Bellini’s 1831 opera La sonnambula, which Wagner had conducted. The plot hinges on a private somnambulistic episode of the female protagonist that places her in a potentially compromising situation that is misunderstood; her innocence is only established by a second somnambulistic episode that is observed by the entire community. The somnambulistic experience itself is not explored. It is characteristic of Wagner’s radical approach that what Senta psychologically experiences in a profound way is shown as becoming so vital as to challenge our perception of reality. This idea echoes throughout the rest of Wagner’s oeuvre, for example, in Tannhäuser’s response to the Pilgrims after his miraculous relocation to the Wartburg as well as in his “Rome Narration,” in Elsa’s vision of Lohengrin, in Mime’s “Verfluchtes Licht” soliloquy after the Wanderer’s visit in Act 1 of Siegfried, in Hagen’s twilit dream scene with Alberich and Siegfried’s death scene in Götterdämmerung, as well as in Amfortas’s first lament and Parsifal’s response to Kundry’s kiss in Parsifal. It is a guiding idea for the lovers throughout much of Tristan und Isolde. Wagner became acutely aware that such psychologically distinctive characters and their altered states of consciousness were not readily transparent or comprehensible to others, including the singers he required to bring these characters to life onstage. Wagner’s many plans for operatic reform in Germany included better dramatic training opportunities for opera singers, and his expectations for his own works were on an altogether different plane from anything he encountered in contemporary theatrical practice.

Dresden afforded Wagner his first opportunities to bring his own operas to the stage in a fully professional context, with substantial resources available for production. Rarely did he know in advance which singers would create his characters onstage. For the role of Senta (as well as Adriano in Rienzi and later Venus in Tannhäuser), Wagner was able to work with the very singer who created the first strong impact on his notion of the ideal opera performer. Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient’s persuasively acted performances that so impressed Wagner in his youth remained uppermost in his mind when he began creating such atypical operatic characters as Senta.15 Past her prime by the mid-1840s, Schröder-Devrient was no longer as compelling onstage, especially in the voluptuous role of Venus, yet her critical understanding of Wagner’s goals remained acute. She recognized, as Wagner painfully did, too, that Josef Tichatschek was fully capable of singing the role of Tannhäuser but completely unable to understand the character’s complexity and the gravity of key moments in the drama.16 Wagner worked painstakingly with Tichatschek, whom he thought a better Lohengrin than Tannhäuser, but came much closer to his ideal performer only twenty years later with the tenor Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld, who created the role of Tristan (1865). Wagner knew from these early experiences that the roles he was creating would be difficult to cast well, especially dramatically, yet he continued moving ever further in the same direction.

As Kapellmeister in Dresden, Wagner was not only concerned with the creation and production of his own operatic works, but with the theater in general and its ability to produce a range of repertoire. In the heady revolutionary days just before Wagner began his long term of exile outside Germany, he wrote a report proposing a series of reforms intended to improve the level of quality of performances, provide better support for all employees (including theater poets and composers), and reduce less successful activities so that the overall budget was a little tighter and more balanced.17 Once exiled to Zurich, Wagner focused more exclusively on his own artistic activities, pursuing with renewed energy a revolutionary path. As for the performances of his existing stage works, he was indebted to his friend Franz Liszt for undertaking a revival of Tannhäuser (1849) as well as for the premiere of Lohengrin (1850) in Weimar. Unable to participate directly in productions of his own works during those years, Wagner wrote two essays concerning Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser that give us detailed insight into his views about optimal rehearsal conditions and handling of stagecraft and describe how he, as Regisseur, would direct singers to interpret their roles in key scenes. Although the term Regisseur had been used in spoken theater since the 1770s and the role soon came to involve dimensions that we associate with stage directors today, Opernregisseure at this time were far less involved with dramatic interpretation.18

Wagner begins the essay “Über die Aufführung des ‘Tannhäuser’” (On the production of Tannhäuser)19 by proposing that the current division of labor of stage direction, musical direction, and set design does not support dramatic coordination and that the Regisseur should play a larger interpretive as well as mediating role. With more than a little disdain Wagner refers to the “book” usually used by stage directors in their main task of blocking of characters. Production books (livrets de mise en scène) had become a specialty in Paris in part due to the practical need to organize the large number of people that move about stage in grand opera and opéra comique. The production book for Le prophète (1849), for example, is an elaborate, semi-choreographic record including many details about gestures and poses (meant to signal an understanding of characters’ emotions or motivations), lighting, and costumes.20 It does not include a complete libretto nor is there any indication of the stage directions actually published in the score; the manner of cuing when something is to happen involves references to the appropriate fragment of text and occasionally to the beginning or ending of a clear-cut musical section; otherwise there is scant mention of the musical part of the score. In German-speaking regions at this time, the Regiebuch or Dirigirbuch was more typically a version of the Souffleurbuch, the prompter’s copy of the libretto, into which similar types of details were written.21 Wagner asks that the Regisseur study the score, in which the relationship between his stage directions and music is clear, while seeking the conductor’s assistance. At the same time, he urges the conductor to study the libretto, which would have been the common focus of all involved in rehearsals before preparation of the musicians got under way.

Working at a distance from theaters mounting his operas, Wagner outlined what he felt needed to happen to avoid pitfalls that he himself had encountered in producing these works and those which he felt were likely to happen if performance and production norms prevailed. As follow-up to his critique that singers are primarily concerned with technical execution and only remotely with the drama, Wagner claimed that his work demands “an approach to performance directly opposite to the usual” (“ein geradesweges umgekehrtes Verfahren als das gewöhnliche für seine Darstellung”).22 Wagner was completely opposed to all routine manners of gesture and blocking not specifically meaningful to what was happening onstage. At the same time he emphasized that he was creating works with uncommon scenarios and characters that involved a special sensitivity in their portrayal. Whereas in production notes he could specify precisely at which beat of a measure the Dutchman should take a further step toward land as he disembarks from his ship, such directions are less of a rigid road map than a way of explaining how a man so weary would disembark so slowly. The simple stage direction in the score for the Dutchman to descend to the stage does not make clear the pacing, nor how he might also be reluctant to again search for a faithful wife, something which becomes clearer only in the course of his monologue. A good example of how Wagner’s expectations might be counterintuitive to contemporary practice or to an interpretation based on the libretto alone is evidenced by the amount of physical restraint he wished the Dutchman to show during much of his monologue; the protagonist is obviously frustrated, which could well encourage a good deal of flailing about onstage. But the Dutchman’s frustration is not fresh and he has already reached a stage beyond hopefulness, most originally and effectively conveyed in the hushed otherworldly interior section of his monologue concerned with the redemption clause offered him by “God’s angel.” As he begins another phase on land, he is to convulse at the onset of this middle section and then collapse after the negating climax, before the relentless musical ritornello drags him back into the rendition of his cursed state. His appeal to divine forces is actually an anti-prayer that underscores how he has no faith or desire to participate in the process already under way.23

Wagner never imagined that the score could bear the amount of detailed stage directions necessary to convey how a singer or conductor might arrive at a completely satisfactory understanding of text and music and how they should be performed. Interpretation for Wagner was a matter of study and reflection, a process that combined the efforts of many performers of which he, in the role of Regisseur, was typically the most lively and committed. Traces of the process of interpretation can be found in the many reports of those with whom he worked and those who observed his working methods, as well as in entries written into rehearsal scores.

The records that exist of Wagner in action are remarkable and varied, beginning from the brief time he was active in Munich under the patronage of Ludwig II. A greater reverse of fortunes is scarcely imaginable.24 After years of working in relative isolation and with limited but frustrating attempts to produce his operas, Wagner was suddenly granted the opportunity to bring several of his works to the stage through the extreme generosity of the freshly crowned young king, while also gaining the support he needed to continue working on his ambitious but still incomplete Ring cycle.

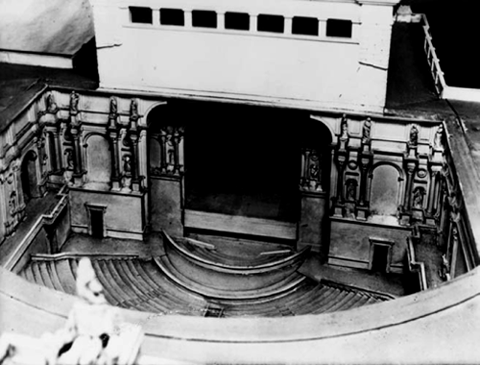

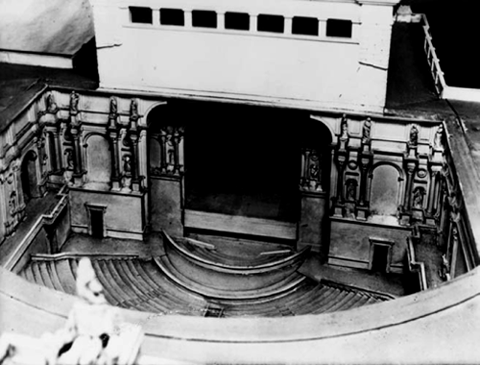

Wagner’s welcome in Munich was, at best, a deeply divided one, and he swiftly wore it out. But during the time he was active there he was given opportunities that helped crystallize his ideas about preparing and carrying out productions of his works that would spill directly into the realization of his own theater in Bayreuth. His persistent claim to need his own special venue for producing the Ring reflects Wagner’s belief that no existing theater in Germany had a resident ensemble and orchestra strong enough, or the necessary stagecraft, to cast and perform his post-Lohengrin works. Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger demanded relatively little in the way of extraordinary stage effects, but much in terms of musical preparation. Ludwig soon began exploring the idea of a special theater for the Ring in Munich to be designed by Gottfried Semper. Semper eventually produced three different models, trying to cater to both the king’s desire for a magnificent theater on the bank of the Isar and to Wagner’s more modest wishes. Semper’s models feature characteristics that Wagner would take over as he built his own theater in Bayreuth: an amphitheater-like auditorium, double proscenium, and sunken orchestra—all features intended to focus the audience’s intentions on the drama onstage.25 Though Wagner’s written report to the king concerning an affiliated national singing school made it clear that he encouraged the training of a pool of talent, he was already committed to preparing his works along the lines of the festival model, drawing the best singers from houses all over Germany.26

The first modern style “arts festival” in Munich was a group of spoken theater performances organized a decade before Wagner arrived by Franz Dingelstedt, who had written an essay on the occasion of the Weimar premiere of Lohengrin in 1850. It was during his tenure as Intendant of the Munich Hof- und Nationaltheater that Dingelstedt organized his Gesamtgastspiel or “collective guest performance,” as he called it. Dingelstedt pooled the best actors for a series of model performances of classic German works outside of the regular season in the summer of 1854 (the same summer he had promised to produce Wagner’s Tannhäuser; that plan was put off until the following year). For his own series of model productions in 1864-65, Wagner drew upon the orchestra, production staff, and physical resources of the Hoftheater, but he had freedom to choose singers from elsewhere.27

Figure 1. Gottfried Semper’s model for a Wagner theater in Munich.

For Holländer in 1864, Wagner served as Regisseur and installed himself as conductor. Generally pleased with the musical results, he nonetheless realized again how difficult it was to bring off the stagecraft side of this work satisfactorily. A far greater and different challenge lay in the premiere of Tristan und Isolde on June 10, 1865. Having found in Schnorr von Carolsfeld a singer of rare sensitivity and responsiveness, Wagner committed himself fully to coaching his interpretation of Tristan, as the vocal pedagogue Julius Hey reported:

Then the imposing figure of Schnorr moved forward into the circle of performers. Curiosity on every face! … I could at most describe the impressions that Schnorr’s powerful presence, voice, and dramatic presentation made on his colleagues in the course of the rehearsals. For all present, Wagner’s rapport with this exemplary singer conveyed a wholesome lesson, providing insight into the meaning of the work itself as well as the nature of its creator in his role of a master of interpretation [Vortragsmeister]. More and more, all of those involved recognized that precisely in this capacity Wagner had extraordinary things to offer. Largely as a result of Wagner’s inspiring guidance, the evening’s rendition exerted on all such a surprising impact that the composer could justifiably assert that it had exceeded his wildest expectations.28

Schnorr’s death a few weeks later, on July 21, was a tremendous blow to Wagner, who admired the singer’s artistry at length in an essay for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.29 Further clouding this great artistic accomplishment was the rapidly escalating political opposition to Wagner’s undue influence on the Bavarian king, and the uncomfortable atmosphere resulting from his less than smooth handling of his affair with Cosima (née Liszt), then wife of the conductor of the Tristan premiere, Hans von Bülow. Ludwig defended Wagner as much as he felt he could at this time, but he could no longer support him in Munich past the end of the year. Soon Wagner was again in exile, this time in Tribschen, Switzerland, and his involvement in the preparation of the three ensuing Munich premieres—Die Meistersinger (1868), Das Rheingold (1869), and Die Walküre (1870)—dwindled radically. Still, Wagner had formed a network of professional relationships that were to bridge what otherwise might seem a mostly hostile divide between his activities in Munich and Bayreuth.30 Albeit more coolly than before, Ludwig continued to support Wagner financially as he moved toward realizing his idea of a festival theater in Bayreuth, in Bavaria’s northernmost region. Individual artists connected to Wagner’s work in Munich also contributed to the new project. Julius Hey, the keen observer of the Tristan rehearsals, for example, served as vocal teacher in Bayreuth. Franz Betz, who created the role of Hans Sachs, went on to sing the role of Wotan in the first complete Ring cycles. A young Heinrich Vogl (1845-1900) sang Loge both in Munich (where he also sang Siegmund) and Bayreuth, where he also performed in the first revivals of the Ring at Bayreuth, in 1896 and 1897, under the direction of the composer’s widow Cosima Wagner.

Crucial to the Bayreuth project was the entire technical setup of the theater, an area where Wagner needed to rely most on experts.31 Ludwig had obliged Wagner by having certain improvements made to the stage of the Munich Hoftheater for the demanding scenic effects in the two individual Ring operas produced there. Although the special effects may not have been optimally realized, Wagner recognized that he could work with few better machinists than Carl Brandt as he set out to build his own theater and equip it in the best possible manner. In the area of scenic and costume designs, Wagner usually left the details of execution up to other artists and machinists so long as they were naturalistically rendered and the stagecraft was sophisticated and efficient enough to integrate special illusions relatively seamlessly.32 He was far less bound up with the growing trend toward historical detail in set and costume design than were many of his contemporaries and successors, including Ludwig and Cosima. This lack of visual fussiness was part of his basic premise that matters of design should not be distracting for their own sake. The goal was always to convey a somewhat dreamlike world.33 The technical challenges in attaining that dreamlike world were more problematic with the Ring than with Parsifal, and it is hard to avoid thinking that Wagner’s willingness to experiment with new technology might have found better solutions a few years into the future, as developments in electricity and lighting technology enabled new design possibilities and major shifts in production aesthetics.

Figure 2. Wagner directs Franz Betz in the role of Wotan.

Wagner’s work at Bayreuth made intense and lasting impressions on everyone with whom he collaborated. Although he himself would not direct revivals of either the Ring or Parsifal, his conductors, singers, designers, and machinists all played a direct role in the ongoing life of these artworks, in Bayreuth and elsewhere.34 And of course there was Cosima, the woman who devoted herself with the zeal of a martyr to the success of her husband’s enterprises. Starting in 1869, the year before their legal marriage, Cosima began painstakingly recording in her diaries a myriad of details about the creation and production of Wagner’s works. Following Wagner’s death, a half year after the successful premiere of Parsifal, Cosima found ways to resume the festival (not annually at this stage), ardently championing and defending her husband’s practices and wishes as she recalled them. She maintained Parsifal as the festival’s backbone, preserving the 1882 production as long as possible. Wagner himself had seen Parsifal as the financial solution to his family’s future; he had gone to lengths to exclude it from his arrangement with Ludwig of handing over performance rights to his operas as repayment for debts from the Ring premiere. With the Berne Convention for the protection of Literary and Artistic Works of 1886, Cosima was able to prevent other performances of Parsifal from taking place in most of Europe during the three decades following Wagner’s death. The original production was virtually frozen in time until Siegfried Wagner began to modify the sets in 1911.35 Cosima’s efforts to continue the Bayreuth festival project were nothing short of Herculean, especially as she began adding to Wagner’s repertoire operas that had not been previously staged there. However, a balanced appraisal of the singers who worked only with Cosima reveals a rigidity in her approach to gesture as well as vocal declamation that contradicts Wagner’s more flexible approach to acting, which, as Patrick Carnegy argues, “should retain, within limits, an essential element of improvisation.”36 Despite her surely good intentions, Cosima’s lack of involvement as a singer, pianist, or conductor perhaps prevented her from achieving an even closer relationship to Wagner’s own practices as a stage director.

Wagner was certainly ambitious in regard to stagecraft, but the most important influence he exerted as Regisseur was on the musicians he worked with closely in Bayreuth and who embraced the process of dramatic-musical interpretation he espoused. Angelo Neumann—decidedly not an artist, but an ambitious impresario who would take the Ring on tours of incredible scope—sensed a seismic change when he attended performances in Bayreuth in 1876: “To be sure, I had already learned to admire Richard Wagner as a stage director in Vienna, but through the performance of Rheingold it became clear to me that new and unprecedented challenges had been posed by the greatest of the world’s stage directors [and] that from then on a new epoch of reform was under way.”37

In addition to the care that Wagner paid to stage design and technology, he took exceptional care with specific roles that were less certain to make their mark on the public. For the role of Siegfried, for example, Wagner chose a singer whose vocal technique was rather immature, as was his acting technique. Capitalizing on the overall naïveté of Georg Unger, Wagner groomed the performer with Julius Hey’s assistance in a manner that suited his gradually emerging hero. In the environment of Bayreuth Wagner thrived as “schoolmaster Mime” (Hey’s words) in coaching this raw talent:

This rehearsal of the first act of Siegfried was unforgettable! Wagner marked not only Mime’s key words, but he sang the part through the entire act with full voice!! And how he sang his “schoolmaster Mime.” Unger’s mouthy, colorless singing tormented me, and I listened to it without interest, whereas the master teacher offered an incomparably characteristic expressive rendering (although he did not at all possess a trained voice in the normal sense); he created without caricatured awkward physical gestures [Gangeln und Gehn] a character of such sharp, strongly etched depiction, the likes of which one would perhaps never experience on the stage!38

Unger was not fully adequate in performance in Bayreuth, but Wagner continued to work with him and regarded him as key to future performances of his operas. Several of the singers Wagner coached in Bayreuth already possessed better technique and more effortlessly conquered stages as his acting emissaries: Franz Betz, Karl Hill, Albert Niemann, Amelie Materna, Emil Scaria, Lilli Lehmann, and Marianne Brandt.39 While the Bayreuth stage remained dark following the financial disaster of the 1876 premiere of the Ring, which had been far from satisfactory in terms of stagecraft, many of the original cast participated in the first performances of the complete Ring elsewhere, as in Munich in 1878. Several of these singers also participated in the touring production of the Ring led through Europe by Neumann in 1882-83.

A subset of Wagner’s singers embraced the role of operatic Regisseur themselves, emulating their dramatic coach in an era when the title had not yet acquired much meaning beyond someone who controlled onstage traffic. Swedish bass Johannes Elmblad sang in the Ring at Bayreuth in 1876 and then again in 1896, as well as in revivals through to 1904, around the time it seems that Cosima became uncomfortable with his competing views on Wagner’s intentions about staging.40 Elmblad sang at the Metropolitan Opera in the 1887-88 season when Anton Seidl was active there. During his return to the Met in 1902-3, he mostly directed Wagner operas and sang his farewell performances as Hunding, in a production he also directed. In 1907 he was responsible for directing some of the performances of the first complete Ring in Stockholm. Anton Fuchs, who premiered the role of Klingsor in 1882, directed the hotly debated production of Parsifal in 1903 at the Metropolitan in New York (while copyright was in effect elsewhere). Especially with Parsifal, a personal link to the premiere production was prized on other stages.

If there is one primary heir to Wagner’s legacy as Regisseur, that role can only belong to Anton Seidl, the young conductor who became an indispensable member of the theater team as the complete Ring came to the stage and a member of the Wagner household until 1878 as the composition of Parsifal neared completion. Through years of copying the scores for the Ring (and half of Parsifal), participating in rehearsals for its premiere, and studying all of his operas with the composer, Seidl became uniquely qualified to take Wagner’s place in preparing his operas for the stage. Had the orchestra from Munich not arrived equipped with its resident conductor Hermann Levi in 1882, Wagner would have entrusted Seidl with the premiere of Parsifal. There was nobody else as gifted in musical interpretation who understood the intimate relationship between the music and stage as Seidl. Despite Wagner’s huge reservations about a revival of Tristan und Isolde in Leipzig, given the massive challenges entailed in bringing it to the stage the first time, Seidl had scored a major success with the work. Following a report of the event by Neumann, then Intendant in Leipzig, Wagner replied in a letter dated 16 January 1882 “I also beg you for the sake of the whole, to give him more authority over the scenic disposition than is usually granted to conductors, for herein lies what he has especially learned from me.”41

Seidl’s close identification with the Ring in these years was confirmed by the far-ranging tour of Neumann’s “Traveling Richard Wagner Theater,” during which Seidl conducted nearly 135 Ring performances and 58 concerts between September 1, 1882, and June 5, 1883. Seidl took note of all these performances in a small notebook, a study in understatement given the nature of the enterprise:

Friday Sept. 1 early little concert: rehearsal, evening concert 7 o’clock. Succeeds fabulously. The 2nd: first performance of Rheingold: aside from a few minor errors, goes well. Performance from 7-9:30. The 3rd: Walküre. Much imprecision in the orchestra in the first act; the rest of the performance very good. Much enthusiasm from the audience. The 4th: repetition of Walküre. Goes very well. 6:30-10:30.42

Figure 3. Anton Fuchs as Klingsor.

From its first complete performances in a specially built festival theater with an elaborate setup, the Ring had become a compact show that traveled by rail to play in many theaters of varying capabilities.43 For all of Wagner’s ambition and vision of how the Ring could be produced using elaborate stagecraft, such a tour placed the greatest burden of success on the more fundamental levels of the musical-dramatic rendering. It is worth noting that Seidl was only thirty-two at the time—youth was surely an asset for the troupe’s grueling performance schedule (although he was also known for sleeping late). Seidl had arrived in Bayreuth when he was twenty-five. He quickly became aware of the concurrent levels of theatrical activity involved in the enterprise, as evidenced by the notes he took during the Ring rehearsals. Upon two pages of the notebook he used during this time we can see entries on the printed staves concerning the transition to scene 3 of Das Rheingold as Loge and Wotan descend to Nibelheim in search of Alberich. Seidl notes the emergence of pallid mist (fahle Nebel) in conjunction with Loge’s query “Was sinnt nun Wotan so wild?” (What wild thoughts are Wotan’s?) as well as the Schwefeldampf (sulfur vapors) in connection with Loge’s call to Wotan to slip with him into the rock’s cleft. Stressed on the page’s lower lines are the dynamic levels of the dotted rhythmic figure associated here with the anvils, and these performance directions are repeated at the top of the facing page (see Figure 4). Stage directions in the score make clear when Wagner’s much-loved steam machines were to come into play, but they lack details about how the machinery would be used to achieve such special effects. The rest of what is written on this page concerns the ways in which Alberich’s various disappearances would be handled, specifically the floor traps that would enable him to disappear while concealed by a column of smoke. The trap would take him out of sight completely—“Versenkung ab. (ganz)”—before the mist disappeared and Wotan and Loge arrived in Nibelheim. Later, when Alberich transforms himself into a toad while wearing the Tarnhelm, the trap would lower him until only his head was above stage (“bis zum Kopf ab”) and then raise him halfway up (“Halb auf”) when Loge is to seize him by the head. From the onset, Seidl embraced the Wagnerian theatrical world in toto.

Figure 4. Page from Anton Seidl’s notebook during rehearsals for the Ring in 1876.

It is hardly surprising that early in Seidl’s treatise “On Conducting,” clearly written in homage to the man who groomed his career as a great Wagner interpreter, he recalls a moment before the stage rehearsals for the Ring began when Wagner took him and another young colleague behind the scenes. As recalled, Wagner told them that they “must assume responsibility on the stage for everything that has anything to do with the music—that is, you must act as a sort of musical stage manager.”44 From the stages of Europe to New York and the American Eastern seaboard, where Seidl established Wagner’s operas as theater, he carried out his work in a wide array of production environments, always ready to support and defend vibrant and sensitive dramatic interpretations.45

It is perhaps worthwhile to remind ourselves again of the atypical operatic scenarios that Wagner created and the ease with which they could be misinterpreted onstage. In his defense of the serious dramatic nature of Siegfried’s death scene, for example, when the hero relays what he has learned from the Woodbird, Seidl critiqued the practice of adopting “an utterly unnatural comic falsetto tone to make it seem as if a bird’s voice might be imitated by a tenor.” Instead, Seidl argued for a “Siegfried, who did not twitter the words of the bird to the men, but told them in a simple manner what the bird had sung.”46 Wagner commented upon the unusual paths that many of his idiosyncratic characters follow while coaching Seidl on the first act of Holländer in the fall of 1877. Wagner was then working on the first act of his final stage work, Parsifal. Cosima Wagner recorded the following: “From Holländer to Parsifal—how long the path and yet how similar the character!—Following the music, R. talks about the influence of the ‘cosmos,’ the outside world, on characters who, though basically good, do not perhaps possess the strength to resist it, and who then become quite exceptionally bad, indeed perverse.”47

Following Wagner’s death, Seidl remained a warmly embraced member of the Wagner family. In 1885-86, he began to lead German seasons at the Met. Critical to the success of many of Wagner’s operas in this time was Seidl’s ability to bring singers who had worked with Wagner and himself in Europe to New York. Seidl also fanned the flames of interest in Parsifal in semi-staged performances that deferred to Cosima’s wishes. Finally, she offered him the chance to conduct at Bayreuth, for the 100th performance of Parsifal in 1897. Seidl died in March of the following year. According to Joseph Horowitz, Seidl was, unlike Wagner, “poised and mysterious, undemonstrative and impassioned, attractive and remote,” with the adjectives “magnetic” and “electric” often surfacing in reviews of his performances at the Met.48 In some ways, Seidl trumped Wagner as the perfect performer. Yet his natural and flexible approach to dramatic pacing owed a great deal to Wagner, and this was perhaps the most challenging idea for Cosima to grasp and maintain.

In the case of Tristan und Isolde, for example, Seidl wrote how his primary concern in conducting the passages of Tristan’s grave illness in Act 3 was to accommodate the idiosyncracies of a given performance.49 In stark contrast is the 1936 publication by Anna Bahr-Mildenburg, in which she advances her detailed description of a strict and near continuous mimesis for the principal characters in Tristan und Isolde.50 The extent of movement and degree of histrionics she calls for often work against Wagner’s stage directions and practices, yet the account is offered as an authentic staging tradition emanating directly from Wagner. Bahr-Mildenburg sang at Bayreuth from 1897 until 1914, where she studied several roles under Cosima. As Nicholas Baragwanath argues, contemporary accounts of a naturalness and economy of gesture in her performances of Isolde in 1903 in Vienna may reflect the tempering influence of Gustav Mahler, with whom she had worked since 1895.51 The revolutionary Wagner performances that Mahler began to shape together with the stage designer Alfred Roller from 1903 to 1907 mark the first important break—and a highly successful one—from staging practices at Bayreuth.52 Utilizing light as a powerful dramatic medium in and of itself, Mahler and Roller moved toward a simpler design aesthetic. Fundamentally important, however, remained musical-dramatic interpretation.

Late in 1903, Cosima faced her greatest contest to date when Heinrich Conried managed to produce Parsifal at the Met in New York, free from Berne restrictions. Ernst von Possart, Cosima’s rival in producing Wagner’s operas in Munich since 1894, supported Carl Lautenschläger’s sharing his expertise concerning the original stage machinery of Parsifal, and the stage of the Met was renovated so as to meet or exceed the technical capabilities in Bayreuth. Anton Fuchs, of the original Parsifal cast, directed the performances and Alfred Hertz conducted. Cosima vowed never to work again with anyone affiliated with this New York production; Hertz never conducted in Germany again. By this time, Fuchs had devoted himself to stage direction. From November 1903 until December 1904 he acted as director for twelve productions at the Met, including a new Ring with the conducting split between Felix Mottl, who assisted Richter in Bayreuth for the premiere of the Ring and was at this time a guest at the Met, and Hertz, as well as new productions of Tannhäuser and Meistersinger. Fuchs also directed the 1914 premiere of Parsifal at Munich’s Prinzregententheater, where he had already directed the Ring and other Wagner repertoire since the theater opened in 1901.

Figure 5. The opening scene of Das Rheingold (1906) as directed by Anton Fuchs in the Prinzregententheater.

Fifteen years after Ludwig’s death in 1886, his dream of a Wagner theater in Munich was realized with a modified version of Semper’s plans. The project to build the Prinzregententheater was spearheaded by Possart, Intendant of the Hoftheater and fittingly, perhaps, one of Germany’s greatest actors. Whether in Munich, Vienna, or New York, the intense interest in producing Wagner’s most ambitious music dramas, including Parsifal, made the opening years of the twentieth century challenging ones for Cosima Wagner, as she attempted to hold on to some unique vestige of Wagner’s legacy. Although Anton Seidl had passed from the scene, and only a few singers who had worked directly with Wagner remained active, a generation of expertise with the later stage works continued to bear fruit, nurturing strong production traditions that in a variety of ways endeavored to keep alive Wagner’s ideas about dramatic interpretation.

Figure 6. Under the photo sit Ernst von Possart and (to his right) Anton Fuchs. Further to right (seated): conductors Hermann Zumpe, Franz Fischer, and H. Röhr, each of whom would conduct the production of Götterdämmerung (playbill hanging in rear) that Anton Fuchs directed and premiered in the 1903 festival. Photo possibly from that year, when Zumpe and Fischer both conducted. Röhr holds in his hand what appears to be the playbill for the world premiere of Die Feen that Fischer conducted in Munich in 1888. Seated to Possart’s left: the stage machinist Carl Lautenschläger, stage director Jocza Savits, and W. Schneider.

1. Although eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century stage direction practices in Italy were mostly uneven, theater poets often played a role in blocking and role preparation. Pietro Metastasio was exceptional in the specificity of the dramatic realizations of his work; to this end he remained involved in the rehearsal process. See Gerardo Guccini’s “Directing Opera,” in Opera on Stage, ed. Lorenzo Bianconi and Giorgio Pestelli, trans. Kate Singleton (Chicago and London, 2002), 125-76, esp. 134-42.

2. On aspects of the work and its genesis, see Richard Wagner: “Der fliegende Holländer,” ed. Thomas Grey (Cambridge, 2000). Other early works, especially Rienzi, are important in tracing the development of Wagner’s mature aesthetic strategies, but the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer is especially distinctive.

3. Although H. Robert Cohen has drawn substantial attention to these production books in several publications reaching back to the late 1970s, his assertion that these books documented Parisian premieres for replication elsewhere has been challenged. A more flexible understanding of opera production practices and these important documents emerges in Arne Langer’s in-depth study Der Regisseur und die Aufzeichnungspraxis der Opernregie im 19. Jahrhundert (Frankfurt am Main, 1997). Arnold Jacobshagen’s reassessment of the dating of production books shows how they reflect different moments in evolving production practices. See his article “Staging at the Opéra-Comique in Nineteenth-century Paris: Auber’s Fra Diavolo and the livrets de mise-en-scène,” Cambridge Opera Journal 13/3 (November 2001): 239-60.

4. Patrick Carnegy traces Wagner’s evolving ideas about the theater and their impact on his operatic activities in Part 1 of his Wagner and the Art of the Theatre (New Haven and London, 2006); see esp. 15-25 for a description of theatrical offerings in Paris. Mathias Spohr broadens the lens beyond technology in his examination of the influence of melodrama, from the period of Wagner’s youth through to the popular forms of theater in Paris. See his “Medien, Melodramen und ihr Einfluß auf Richard Wagner,” in Richard Wagner und seine “Lehrmeister,” ed. Christoph-Hellmut Mahling and Kristina Pfarr (Mainz, 1999), 49-89. Dieter Borchmeyer fascinatingly probes dense literary and theatrical contexts of Wagner’s development in Das Theater Richard Wagners (Stuttgart, 1982); trans. Stewart Spencer as Richard Wagner: Theory and Theatre (Oxford, 1991).

5. Wagner: My Life, trans. Andrew Gray (Cambridge, 1983), 226.

6. The texts that were set independently before the libretto was written and the differences between the four versions of the libretto and later published versions are charted in Isolde Vetter’s PhD diss. “Der fliegende Holländer von Richard Wagner: Entstehung, Bearbeitung, Überlieferung” (Technical University, Berlin, 1982).

7. See Grey’s interpretation of the multiple biographical and symbolic implications of these changes in Richard Wagner: “Der fliegende Holländer,” 5-17.

8. Carl Dahlhaus explores this dimension of Wagner’s music in Die Bedeutung des Gestischen in Wagners Musikdramen (Munich, 1970). For an account that considers Wagner’s indebtedness to other composers, see Mary Ann Smart, Mimomania: Music and Gesture in Nineteenth-Century Opera (Berkeley, 2004), esp. 163-204.

9. David Levin considers Senta’s unusual perspective in contrast with that of those around her in “A Picture-Perfect Man? Senta, Absorption, and Wagnerian Theatricality,” Opera Quarterly 21/3 (Summer 2005): 486-95.

10. “Senta hält vor Erschöpfung an, —die Mädchen singen leise weiter.”

11. “Ach! wo weilt sie, die dir Gottes Engel einst könne zeigen?/Wo triffst du sie, die bis in den Tod dein bliebe treueigen?”

12. “Senta setzt sich erschöpft in den Lehnstuhl nieder; bei dem Beginn von Eriks Erzählung versinkt sie wie in magnetischen Schlaf, so daß es scheint, als träume sie den von ihm erzählten Traum ebenfalls.”

13. For a survey of animal magnetism in Wagner’s time and in literature, see Reinhold Brinkmann, “Sentas Traumerzählung,” in Die Programmhefte der Bayreuther Festspiele (1984) 1:1-17. Brinkmann is skeptical of Wagner’s actual knowledge of the practice/phenomenon and regards the allusion as fashionable among Romantics but as ultimately unhealthy. Of the many other artistic figures also interested in animal magnetism, E. T. A. Hoffmann must be counted as an especially strong influence on Wagner during this time. As with Der fliegende Holländer, somnambulists and magnetic states in his literary works serve as thematic material that impacts the shape of the narrative. If we accept the premise of her somnambulistic tendencies, which is not a popular modern critical approach, Senta does not have access to her brazen ecstatic outbursts, which she contradicts when she is in a normal state of consciousness. Carolyn Abbate reads Senta’s inconsistencies as “hysteria and spiritual chaos” in “Erik’s Dream and Tannhäuser’s Journey,” in Reading Opera, ed. Arthur Groos and Roger Parker (Princeton, 1988), 139. Rarely noted is that Senta’s strange psychological behavior ceases when she actually meets the Dutchman.

14. Sarah Hibberd carefully distinguishes somnambulism from madness in French stage works of the late 1820s and illuminates the rich web of musical allusions that Hérold employed in conjunction with Thérèse’s somnambulistic tendencies. See her article “‘Dormez donc, mes chers amours’: Hérold’s La Somnambule (1827) and dream phenomena on the Parisian lyric stage,” Cambridge Opera Journal, 16/2 (July 2004): 107-32.

15. Wagner’s own accounts of his early experiences of Schröder-Devrient in performance have often been questioned for their accuracy. The fact remains that he was deeply impressed by the conviction of her performances, which superseded the limitations of her vocal gifts. On Schröder-Devrient’s career and her influence on Wagner, see Part II of this volume.

16. Ernest Newman, The Life of Richard Wagner (New York, 1933), 1:397.

17. “Entwurf zur Organisation eines Deutschen National-Theaters für das Königreich Sachsen.” in Richard Wagner, Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen (henceforth GSD), 10 vols. (Leipzig, 1887-1911), 2:233-73.

18. For a detailed history of the evolution of the Regisseur, see Langer, Der Regisseur und die Aufzeichnungspraxis.

19. Wagner, GSD, 5:123-59; here, 124-30.

20. A facsimile of this production book is published in H. Robert Cohen and Marie-Odile Gigou’s The Original Staging Manuals for Twelve Parisian Operatic Premières (New York, 1990), 151-82.

21. Langer, Der Regisseur und die Aufzeichnungspraxis, 157.

22. Wagner, GSD, 5:127.

23. The dramaturgy of this monologue is closely connected to “Senta’s Ballad,” at some moments in markedly inverse ways. The Dutchman has no interest in seeking a redeeming wife and possibly implicating someone further in his curse—a benevolence that he expresses when he sets off to sea, leaving Senta on land.

24. During the years preceding his time at Munich, he was only able to be involved directly in two projects. Lavish sets, excellent stage coordination and choral singing, and some fine performances by the soloists could not outweigh the scandalous divided reception and personal financial disaster of Tannhäuser in Paris in 1861. Vienna turned out to be another dead end when orchestral rehearsals for Tristan und Isolde were abandoned in 1863.

25. These plans for a festival theater and the eventually completed theater in Bayreuth are comprehensively covered in Heinrich Habel’s Festspielhaus und Wahnfried (Munich, 1985). A recent dual-language (German-English) publication concentrating on the Bayreuth Festspielhaus is Das Richard Wagner Festspielhaus Bayreuth/The Richard Wagner Festival Theatre Bayreuth, ed. Markus Kiesel (Cologne, 2007).

26. “Bericht an Seine Majestät den König Ludwig II. von Bayern über eine in München zu errichtende deutsche Musikschule,” GSD, 8:174. For a comprehensive discussion of the plans for a special theater in Munich and Wagner’s eventual Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, see Heinrich Habel’s Festspielhaus und Wahnfried: Geplante und aufgeführte Bauten Richard Wagners (Munich, 1985).

27. Detta and Michael Petzet offer a detailed account of the model productions of Wagner’s works financed by Ludwig in Munich (through to Rienzi in 1871) and those mounted by Wagner in Bayreuth in their Die Richard Wagner Bühne König Ludwigs II (Munich, 1970).

28. Julius Hey, Richard Wagner als Vortragsmeister (Leipzig, 1911), 82.

29. The essay, titled “Meine Erinnerungen an Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld,” was published on June 5 and 12, 1868, and is included in GSD, 8:177-94.

30. The background of festival performances in Munich and the strong commitment to performing Wagner’s works past Ludwig’s death is covered in Jürgen Schläder and Robert Braunmüller, Tradition mit Zukunft: 100 Jahre Prinzregententheater München (Feldkirchen bei München, 1996), esp. 9-20.

31. The most detailed account of this dimension of the theater is Carl-Friedrich Baumann, Bühnentechnik im Festspielhaus Bayreuth (Munich, 1980).

32. Still a landmark in the study of the production history of Wagner’s operas is Oswald Georg Bauer’s Richard Wagner: Die Bühnenwerke von der Uraufführung bis heute (Frankfurt/Berlin/Vienna, 1982), trans. Stewart Spencer as Richard Wagner: The Stage Designs and Productions from the Premières to the Present (New York, 1983). For a more analytical and up-to-date perspective, see Mike Ashman, “Wagner on Stage: Aesthetic, Dramaturgical, and Social Considerations,” in The Cambridge Companion to Wagner, ed. Thomas S. Grey (New York, 2008), 246-75.

33. Oswald Georg Bauer, “Die Entwicklung des Bayreuther Inszenierungsstils 1876-1979,” in Wagner-Interpretationen, Beiträge zur Aufführungspraxis 5, ed. Roswitha Vera Karpf (Munich and Salzburg, 1982), 116.

34. In addition to considering the reports of production team members such as Richard Fricke, Heinrich Porges, and Julius Kniese, Martina Srocke also closely considers the entries made by many hands in rehearsal scores in her Richard Wagner als Regisseur (Munich and Salzburg, 1988). Fricke’s diaries have been translated by George Fricke and published as Wagner in Rehearsal 1875—76: The Diaries of Richard Fricke, ed. James Deaville and Evan Baker (New York, 1998), originally published as Bayreuth vor dreissig Jahren (Dresden, 1906). They have also been translated by Stewart Spencer as “Wagner in 1876,” in Wagner Journal 11 (1990): 93-109, 134-50; and Wagner Journal 12 (1991): 25-44. For other accounts of the 1876 rehearsals, see Carl Emil Doepler: A Memoir of Bayreuth 1876, ed. Peter Cook (London, 1979); and Heinrich Porges, Wagner Rehearsing the Ring, trans. R. Jacobs (Cambridge and New York, 1983).

35. For a more detailed discussion of the early production history of Parsifal through to the end of World War I, in Bayreuth and elsewhere, see my “Parsifal on Stage,” in A Companion to Wagner’s “Parsifal, “ ed. William Kinderman and Katherine R. Syer (Rochester, N.Y., 2005), 277-99.

36. Carnegy, Wagner and the Art of the Theatre, 93.

37. Angelo Neumann, Erinnerungen an Richard Wagner (Leipzig, 1907), 20.

38. Hey, Richard Wagner als Vortragsmeister, 110.

39. On the legacy of Wagner’s first Bayreuth festival and some of the singers he trained, see the accounts of the 1886 and subsequent festivals in Part V of this volume.

40. The most detailed information about Elmblad’s extended Wagner activities is found in Stefen Johansson, “Wagners Ring på Kungliga Operan: Regi och framförande-traditioner under ett sekel,” in Operavärldar Från Monteverdi till Gershwin, ed. Torsten Pettersson (Stockholm, 2006), 219-46.

41. Neumann, Erinnerungen an Richard Wagner, 216.

42. “Freitag am lsten Sept. früh kleine Concert: probe, Abends 7 Uhr Concert. Prachtvoll gelungen. Am 2ten: erste Aufführung von Rheingold; bis auf einige leichte Versehen gut gegangen. Aufführung von 7-½ 10. Am 3ten: Walküre. Zum ersten Akt viele Ungenauigkeiten vom Orchester vorgekommen; sonstige Leistung sehr gut. Enthusiasmus im Publikum sehr gross. Am 4ten: Wiederholung der Walküre. Sehr gut gegangen. Von ½ 7-½ 11.”

43. For a vivid account of Neumann’s enterprise and a comprehensive account of the part of the tour that unfolded in Italy just weeks after Wagner’s death, see John W. Barker, Wagner and Venice (Rochester, 2008), 176-240.

44. Henry T. Finck, Anton Seidl: A Memorial by his Friends (New York, 1899), 217.

45. Joseph Horowitz charts Seidl’s American career in detail in his Wagner Nights: An American History (Berkeley/Los Angeles/London, 1994).

46. Finck, Anton Seidl, 211-12.

47. Cosima Wagner’s Diaries, ed. Martin Gregor-Dellin and Dietrich Mack, trans. Geoffrey Skelton (New York, 1978, 1980), 1:990.

48. Joseph Horowitz, “Anton Seidl and America’s Wagner Cult,” in Wagner in Performance, ed. Barry Millington and Stewart Spencer (New Haven and London, 1992), 171.

49. Finck, Anton Seidl, 235.

50. Anna Bahr-Mildenburg, Tristan und Isolde: Darstellung des Werkes aus dem Geiste der Dichtung und Musik (Leipzig/Vienna, 1936).

51. “Anna Bahr-Mildenburg, Gesture, and the Bayreuth Style,” Musical Times 148 (Winter 2007): 65.

52. Mahler’s move to New York in 1907 was launched with revivals of the pivotal Tristan production.