In biographies of Wagner and Liszt the figure of the other always looms large, whether as supported or supporter, borrower or lender, unlikely son-in-law or reluctant father-in-law. At the first Bayreuth Festival Wagner effusively claimed that “not a note” of his music would have been known were it not for the faith of his friend, while in an apocryphal version of Liszt’s death the ailing maestro expires with the word “Tristan!” on his lips.1 Their destinies had been closely entwined since the late 1840s, when Wagner was enduring one of the deepest of his self-inflicted sloughs of despair, and Liszt was distancing himself from the profession of piano virtuoso that had made him famous. The latter’s full assumption in 1848 of the post of Kapellmeister in Weimar heralded an attempt to center the avant-garde of European music in the small but distinguished German town to supplement the literary luster it had acquired in the days of Goethe.2 In the process, Liszt desperately desired to shift his own artistic persona from pianist to composer, from the ephemeral triumphs of the concert stage to the more lasting laurels of the creative artist. On Wagner’s part the needs were more pressingly practical. Exiled from Germany on account of his role in the abortive Dresden uprising of May 1849, he needed money and the means to promote his operas in the native land from which he was now outlawed. Liszt came to the rescue on both fronts.

The traditional view of the situation is that Wagner exploited Liszt—both financially and artistically—and that Liszt allowed himself to be exploited. The traditional view is correct. I do not intend to undertake some perversely implausible “reinterpretation” of the material elements of the Liszt-Wagner interchange, or to claim in twisted tenure-seeking fashion that we have in fact misunderstood the matter—that Wagner was all along the unsung Good Samaritan of the story. Rather, I hope to illuminate some sidelined aspects of the artistic entwining of Wagner and Liszt: the decisive impact that Wagner’s works and theories had on Liszt’s compositional direction, and the complexities of Wagner’s reaction to Liszt’s radically evolving musical style. These areas saw a more subtle exchange than the standard story of the grasping, greedy Wagner, and the long-suffering Liszt would allow. Along the way, I shall chart the most convincing chronicle we have of Liszt’s creative response to Wagner: his transcriptions from Wagner’s operas. They constitute striking evidence of the increasingly divergent musical paths trod by both composers in the latter half of their careers.

The desire for success as a composer rather than as a pianist, more particularly as an opera composer, is a recurrent theme of Liszt’s correspondence in the 1840s. By that time he had finally established himself as the foremost pianist in Europe, a reputation bolstered by a long series of concert tours that garnered unequaled acclaim and unrivaled amounts of money. But though Liszt basked happily in the adulation of the concert-going public, he was well aware that his fame as a virtuoso had always eclipsed his reputation as a creative artist. In a less than wholly enthusiastic review of the Douze grandes études (1837-38), Robert Schumann claimed that Liszt had concentrated on pianism at the expense of his compositional skills and prophesied pessimistically that this neglect would be evident even in his ripest works. It was now, in other words, too late for Liszt to escape his fate. Like an adult struggling to learn a second language, he would never achieve the accent-free fluency of a child mastering a mother tongue.3

But try to escape it he did, and with great energy. From the mid-1840s his hopes for a dramatic breakthrough centered on Sardanapale, an opera after Byron. The Italian libretto had been cobbled together by an anonymous associate of Liszt’s friend and occasionally more-than-friend, Princess Cristina Belgiojoso, luckily a native speaker of a language Liszt understood less than fluently.4 The reason for the choice of Italian was simple. By at least early 1846, and probably even at the time Sardanapale was first conceived, Liszt nurtured hopes of succeeding Donizetti in the prestigious post of court Kapellmeister in Vienna, a much more attractive appointment than the one he would eventually take up in Weimar. He naturally realized that if he wanted to replace a prolific Italian opera composer like Donizetti, experience in composing at least one Italian opera was essential. Liszt seems first to have tested his capabilities in setting shorter Italian texts with the composition of three Petrarch Sonnets for piano and voice, along with “very free transcriptions of them for piano, in the style of nocturnes!” Their success promised much. He proudly told his former partner Marie d’Agoult, “I regard them as having turned out singularly well and more finished in form than any of the things I have published.”5

The biggest problem for Liszt in his desire to succeed Donizetti in Vienna was not simply lack of operatic experience—it was that there was still no official vacancy. Donizetti had indeed been taken seriously ill with tertiary syphilis, but he was still clinging to both his job and his life. And Donizetti, like the proverbial melody, lingered on, steadfastly resisting the grim reaper until 1848. This was too late for Liszt—he was already in the process of settling down in Weimar. He had with him the libretto of Sardanapale, although not a note of the score had been written.

After four years of wrangling over changes to the text, Liszt appears finally to have started to sketch the Sardanapale music in the middle of 1849. He wrote to his amanuensis Joachim Raff in August of that year expressing confidence that the opera would be swiftly finished by the winter.6 But by 1850 he was still optimistically plowing away at it, telling his old Parisian friend and onetime biographer Joseph d’Ortigue: “I am applying myself well to Sardanapale (Italian text, in three acts), which ought to be completed by the end of the year, and in the intervals, I am achieving some of the symphonic works of which I am undertaking a certain series that can only be ready in its entirety in two or three years.”7

In January 1851 he informed Wagner that the opera would be fully finished by spring 1852, to be produced in Paris or London.8 But after this, Sardanapale suddenly vanishes from his correspondence. The triumph he had sought for so long was not to be. Instead, the symphonic works he had been writing “in the intervals” between bouts with Sardanapale became the main focus of his Weimar years, along with piano pieces and, eventually, religious choral music. What happened?

If we are seeking candidates to charge as accomplices to the death of Liszt’s Sardanapale, along with what must ultimately have been the composer’s lack of confidence in his own developing score, two fairly formidable suspects stand in the dock, arms folded defiantly and casting glances of mutual contempt at each other: Liszt’s new partner, the Princess Wittgenstein, and Richard Wagner. But firstly, there is some evidence that the death was as much assisted suicide as murder, evidence compellingly constituted by the libretto. What remains of it seems stilted, wooden, and remarkably old-fashioned. Many passages might not be out of place in a text by Metastasio from the previous century. As Liszt got down to serious work on the music, he must surely have become more and more painfully aware of its drastic shortcomings, and possibly also of his own lack of experience as an opera composer. Moreover, the concluding pyrotechnic conflagration of Sardanapale’s funeral pyre—one of the things that first attracted Liszt to the subject—might suddenly have appeared too clichéd just after the similar final scene Meyerbeer’s Le prophète (1849). It was, of course, also an upcoming special feature of Wagner’s Siegfrieds Tod libretto (soon to be Götterdämmerung).

Liszt’s involvement with opera production in the Weimar theater surely gave him firsthand insights into the dramatic dangers of a limping libretto and of the harm an old-style operatic catastrophe would do to his refashioned reputation as a leading composer. He had certainly not yet proved himself in other major genres—the Beethoven Cantata of 1845 had scarcely made an impact, and his symphonic works were still far from polished. How would his persistent portrayal of himself as the standard-bearer of the musical avant-garde in Germany sit with the setting of a surprisingly dilapidated Italian opera text, especially now that hopes to succeed Donizetti in Vienna had long evaporated?

It seems likely that Princess Wittgenstein was distinctly lukewarm about Sardanapale. The opera was, after all, closely connected to Liszt’s intimate friendship with Princess Belgiojoso, a dangerously seductive “other woman,” and what’s more, another woman of just the type that Liszt tended to go for—titled, talented, and married to someone else. Princess Wittgenstein seems therefore to have directed her indefatigable energies into steering her companion toward symphonic and choral composition. (Only later would she become an operatic muse—not to Liszt but to Berlioz, whose Les Troyens was completed with her insistent encouragement between 1856 and 1858.)

And finally, there was Wagner.

Liszt’s early activities as an opera conductor in Weimar were heavily slanted toward Wagner’s works. He did not only support Wagner on his home ground, he helped to negotiate performances in theaters with which he had little direct connection. He also wrote about Wagner’s achievements in enthusiastic detail, even if his extensive articles were penned with the too unrestrained help of Princess Wittgenstein. Liszt being Liszt, he naturally made piano transcriptions from the operas. These were not for his own concert use, like most of his previous transcriptions, but intended primarily to publicize their source material. In sum, he admired Wagner’s creative endeavors with unqualified enthusiasm and devoted himself wholeheartedly to their support.

It is not surprising that in January 1851, while rejecting Wagner’s insistently well-meaning if typically tactless offer to provide a German opera libretto for him on Wieland der Schmied, Liszt made clear a strong reluctance to compete directly on Wagner’s turf. He was still clinging to his hopes for Sardanapale, because an Italian opera would necessarily be judged by rather different standards:

However great the temptation even for me to forge your Wieland, I can nevertheless not budge from my firm decision never ever to compose a German opera. — I don’t feel any vocation for it, and I’m quite lacking in the patience to struggle with the conditions in German theaters. Altogether it’s much more suitable and more comfortable for me to risk my first dramatic work on the Italian stage (which will probably take place early next year—’52—in Paris or London) and, in the event that things don’t go badly for me, to stick with the Southerners [Welschen]—Germany [Germanien] is your possession, and you its honor.9

Just after signing this letter, Liszt added a significant P.S.: “Are you already far advanced with your book on opera? I’m eagerly looking forward to it…” The book referred to was of course the soon to be celebrated Opera and Drama. Wagner wrote back the following month to say that although no publisher was yet in sight, his “very powerful” polemic was indeed finished.10 Liszt was delighted, largely because he had hopes of finally understanding from Opera and Drama what on earth Wagner had been waffling about regarding opera reform. He admitted he had hardly understood a word of its prolix predecessor, Art and Revolution.

But Wagner had never been one to leave an awkward issue diplomatically alone, and characteristically returned to the attack over Liszt’s own opera plans. From his Zurich exile it must certainly have struck him as strange that Liszt should complain about the difficulty of getting operas produced in German theaters when he himself was the resident conductor in one of them. Not only would any Liszt opera be automatically produced in Weimar under the loving direction of the composer, but there was naturally the expectation that writing operas for the court theater was the sort of thing a Kapellmeister ought to be doing. König Alfred, an opera by Liszt’s pupil Joachim Raff, had just been premiered with some success in Weimar,11 and Wagner—no doubt with the best of intentions—continued to browbeat his hapless supporter:

Raff’s opera pleased me uncommonly, very nice! But further, to say it directly: you must do the same. Write an opera for Weimar—I beg you. Write it for the resources that are available there, and should be improved, ennobled, and expanded through your work. Don’t on my account give up your plans for the Southerners (you can also achieve something famous and flourishing in that area, I know!) but stay also with the things nearest to you, on what is now your home ground…. Don’t bother yourself for the moment worrying about the usual conditions in German theaters; you don’t need them to achieve something both beautiful and useful. To say it openly, what would you want to gain just now, at the height of your present powers, from the southerners apart from an increase in your fame? Good! But will that make you happy? You? Not any more, surely!… Do something for your Weimar!12

Wagner had, for once, a point. There was now a growing psychological block with Liszt about German opera, which would soon seemingly extend itself to all opera. All the more ironic that Liszt’s most ambitious effort as a child prodigy in Paris had indeed been an opera. Don Sanche ou le château d’amour (1825) was a slender one-acter completed with the help of his then composition teacher Ferdinand Paer, but it had nevertheless reached the stage of the most prestigious opera house in Europe in an era when more promising pieces like Berlioz’s Les francs-juges were being roundly rejected. The situation was not dissimilar from that of Mendelssohn, who like Liszt had little problem composing operas as an adolescent, but always found a good reason not to complete one as an adult. On his death in 1847, Mendelssohn’s long-heralded “Lorelei” was in a fragmentary state akin to Liszt’s Sardanapale, though it is impossible to say if it would have been finished had he lived longer.13 Liszt, for his part, found himself in a particularly embarrassing position. He was the Kapellmeister of a small German court, a regular conductor of other people’s operas and a would-be “great composer.” But he himself could only point to a half-sketched opera on an old-fashioned text that had initially been intended for performance in the Italian theater in Vienna, or in Italy itself. The specter of Wagner’s pioneering dramas would hover balefully over anything he did in Germany—partly because of his own selfless success in promoting them. Now even students like Raff had stolen the march on him.

The final nail in the coffin of Sardanapale could well have been the dauntingly vast Wagnerian polemic on the future of opera that Liszt was so masochistically eager to peruse. Opera and Drama was not published in complete form until 1852, but in 1851 Liszt read some advance extracts that appeared as articles in the Deutsche Monatsschrift.14 However difficult Liszt found it to comprehend the convolutions of Wagner’s prose, it must have become quickly clear to him just how little an antiquated Italian offering like Sardanapale would fit in with Wagner’s notions of the artwork of the future. Liszt, usually only too keen to be at the cutting edge of the avant-garde, suddenly found himself potentially to be yesterday’s man.

And so Liszt’s grand designs for an operatic hit met their end, not with some great theatrical triumph or disaster, but by slinking silently into the wings, unfinished and unsung. The symphonic works that he had been writing “in the intervals” while composing the opera now took center stage.15 By 1854 he had even found a new and exciting name for them—“symphonic poem,” rather than the boring “concert-overture,” as most had been called up to that point. Wagner may have played a role here as well. In a letter to Liszt of 1852, he referred to his Faust Overture as a Tongedicht (tone poem).16 One wonders whether this might have had any influence on Liszt’s otherwise unexplained change of nomenclature?

Whatever the origin of the name, a symphonic poem’s “poetic idea” would allegedly inspire the music in the same way as Wagner’s “dramatic idea” would be the breath of life for the opera of the future. With the sketches for Sardanapale consigned to a drawer in Weimar, Liszt would now set to work solving what he called the “symphonic problem” presented to him in Germany. After having spent the best part of a decade dealing with this to his own satisfaction (if not that of his very vocal detractors), he boldly announced in 1862 that he was now ready to tackle “the oratorio problem.”17 Dramatic symphony and dramatic oratorio—orchestral and choral counterparts of Wagner’s music-dramas—would form the core of Liszt’s ambitions for the most fruitful compositional phase of his life. Opera on the stage would be left to Wagner, but there was always opera on the piano.

A profusion of Wagner opera transcriptions flowed from Liszt’s pen.18 But should not the absence of the above-mentioned “dramatic idea”— supposedly so essential to the comprehension of the music—render them unviable from the start, at least in Wagner’s own terms? How can the transcription of an operatic extract hope to work when there can be no “dramatic kernel,” or at least none immediately present to the listeners? When, to use Wagner’s gloriously galumphing phrase coined in the 1872 essay “Über die Benennung ‘Musikdrama,’” no “ersichtlich gewordene Thaten der Musik” (deeds of music made visible) were there at all? Like so many of Wagner’s all too tiresome problems, this one was self-inflicted.

Writing about the first six of Liszt’s symphonic poems in 1857, Wagner could not resist a little sideways swipe at Berlioz concerning this issue. He lamented that in the love scene (Adagio) of the “dramatic symphony” Roméo et Juliette the listener “loses the thread” because the music follows the dramatic course of the scene rather than unfolding according to the “logically clear development of specific [musical] motives.” Berlioz and Shakespeare may have had a certain narrative in mind, but the auditors could not be expected to appreciate this. They ineffectually had to “hold on to scenic motives that weren’t immediately before the eye.”19

Ironically, Berlioz himself shared similar concerns, at least for the “Scene at the Tomb” from the same symphony. He advised in the score that this movement should always be omitted in public performance, “unless played to a select audience familiar in every respect with the fifth act of Shakespeare’s tragedy as conceived and represented by Garrick, and endowed with a highly poetic mind.” So, unless you know exactly what goes on in the fifth act of Romeo and Juliet (with the dénouement de Garrick, of course) you have little hope of understanding Berlioz’s Tomb Scene. The staged narrative is the key to the music.20 Similarly, Wagner was insistent that his own scores were only fully intelligible as part of an operatic production. In 1879 he explained the issue at (for once) reasonable length in “On the Application of Music to the Drama,” where the illustrative example was taken from Lohengrin:

The motive the composer of Lohengrin allots as the closing phrase of a first arioso to his Elsa … consists almost solely of a tissue of remote harmonic progressions; in the Andante of a Symphony, we will say, it would strike us as far-fetched and highly unintelligible; here it does not seem strained, but quite arising of itself…. This has its grounds, however, in the scenic action. Elsa has slowly approached, in gentle grief, with timid down-bent head; one glance at her transfigured eye informs us what is in her soul.21

This was hardly a new idea in 1879. It had formed a central thread of Wagner’s operatic thinking at least since Opera and Drama of 1852. He continued to harp on the topic so insistently that his views were soon common knowledge.

But if the stage setting was so essential for understanding Wagner’s music, where did that leave piano transcriptions, or the concert performance of excerpts from his dramas? Not only did Wagner often conduct the latter, he also wrote concert endings for those that would have trailed off a little too indeterminately in their original incarnation. The point was not lost on a skeptical Eduard Hanslick when he reviewed an 1862 Wagner concert in Vienna. This consisted of extracts from the yet uncompleted Ring cycle and Die Meistersinger. Here Berlioz’s hope that “a select audience” would rely on their memory of a previously staged performance could hardly apply, even if Wagner did provide program notes in an attempt to contextualize the music. With more amusement than malice, Hanslick commented:

It seems noteworthy to us that Wagner can so blithely program such a potpourri from his works—the content of which the public is scarcely even superficially acquainted with—out of context and without the support of scenery. Has Wagner not said countless times that in opera the music is nothing in itself, can be nothing, but on the contrary gets its meaning only in association with the entire action, text, acting and scenery? … The author of Opera and Drama … has indisputably been untrue to himself. Still, it doesn’t occur to us to blame him for it. An artistic disposition has other requirements than consistency.22

The crowning contradiction concerns the most frequently played type of Wagner opera excerpt—in those days piano transcriptions or, as specifically concerns us here, Liszt’s piano transcriptions. It may have been coincidence that the passage from Lohengrin that Wagner claimed would be unintelligible without the scenic action had furnished the material for one of Liszt’s first Wagner arrangements, Elsas Traum, nearly thirty years before—arrangements undertaken with the enthusiastic blessing of Wagner himself. Liszt sometimes included the words in the scores of his transcriptions, but surely this could scarcely compensate for the keenly felt absence of Elsa’s “timid, down-bent head.” Moreover, the early arrangements were effectively collaborative artistic ventures between Wagner and Liszt, although the publicity benefit was, as ever, mostly on Wagner’s side. At no point in the process did Wagner mention any weighty aesthetic objections to transcribed extracts from his opera; nor did he insist that they only be played as accompaniment to a salon staging of the scenes in question, the mistress of the house doing her best to imitate Elsa’s coy glances during crucial modulations. On the contrary, he seemed overjoyed that Liszt had devoted himself to the pianistic promotion of his operas. Hanslick was right: for Wagner publicity was more important than probity.

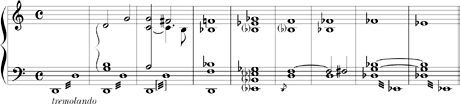

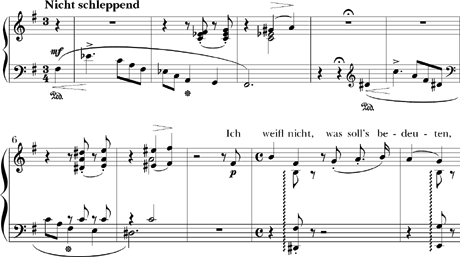

For his part, Liszt later claimed the transcriptions were merely “modest propaganda on the inadequate piano for the sublime genius of Wagner,” but the surviving manuscripts and later revisions show that he took great care in working out the details.23 Even a seemingly simple thing like constructing a few preludial bars to “Isolde’s Liebestod” was approached with unusual imagination.24 He made no fewer than three attempts to find something suitable, starting with the rather too subtle connective tissue that appears in the operatic score, and then replacing it with the theme sung to the words “Liebe, heiligste Liebe” in Act 2. Finally, he hit on a reworked version of the latter as the final formula:

Example 1a. First deleted draft of Wagner/Liszt, “Isolde’s Liebestod,” introduction (Weimar MS. U32).

Example 1b. Second deleted draft of Wagner/Liszt, “Isolde’s Liebestod,” introduction (Weimar MS. U32).

Example 1c. Published version of Wagner/Liszt, “Isolde’s Liebestod,” introduction.

The passages above are clear evidence of Liszt’s improvisatory approach —we can almost hear him trying out the variants on the piano as we read the manuscript. Liszt’s initial engagement with Wagner’s music apparently also involved improvisation, at first on excerpts from Rienzi during his concert tours of the 1840s (although his only published fantasy on that opera dates from much later).25 With the exception of the Ring, from which only Das Rheingold was represented, Liszt’s transcriptions eventually traversed every one of Wagner’s mature works.

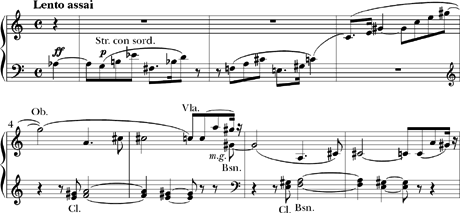

Naturally the first transcriptions to appear in print were connected with Liszt’s Weimar performances of Wagner’s Tannhäuser (1849) and Lohengrin (1850). It was in fact those performances that fostered the close friendship between the two composers. They constitute the most numerous group among the Wagner transcriptions (three excerpts from Tannhäuser and four from Lohengrin) and fall into two distinct classes: works designed for the parlor pianist versus those only playable by top-class virtuosi.26

From the first, however, even the former category was not intended to result in routine arrangement, but something “after Liszt’s unique manner” —hardly a surprise, given that Liszt usually found it difficult to leave well enough alone.27 It is all the more remarkable, then, that he sometimes did attain that level of renunciation when dealing with Wagner’s works. In the “Overture to Tannhäuser,” for instance, he produced a remarkably faithful yet pianistic arrangement. His solution to the problem of the climax of the Pilgrims’ Chorus was so striking in its treatment of the three distinct textural levels of the score that it was transferred over to one of his own original works for piano, the rather unimaginatively named Grosses Konzert-Solo, a preliminary study for the much better-known Sonata in B Minor.28 Here was an example of Wagner influencing Liszt, rather than the other way around, even if through the indirect medium of Liszt’s own transcription.

Example 2. Wagner/Liszt, Tannhäuser Overture, mm. 38-41.

Example 3. Liszt, Grosses Konzert-Solo, mm. 235-38.

Liszt regularly consulted Wagner in his Zurich exile over questions ranging from titles for his arrangements to the structural details of their layout. On the former issue the usually so verbally incontinent Wagner had little to say, on one occasion responding to Liszt’s request for suitable titles with the distinctly dull suggestion: “Two pieces from Tannhäuser and Lohengrin.”29 On the latter point things were different. The formal scheme of Liszt’s arrangement of the Act 3 prelude and “Bridal Chorus” from Lohengrin—two statements of the main material of the prelude framing a treatment of the chorus “Treulich geführt” (“Here Comes the Bride” to English speakers)—was devised by Wagner for his Zurich concerts of May 1853 and quickly taken over by Liszt for his transcription.

If the whole concept of transcribing operatic excerpts was acceptably Wagnerian—at least when it suited Wagner himself—then there was relatively little that could have disturbed him in the slick artistic working out of the early Liszt arrangements. Liszt did admittedly add his own short chromatic coda to the “Song to the Evening Star” from Tannhäuser (Example 4), and dared to vary part of the “Entry of the Guests” from the same opera with the sort of flippant virtuoso figuration Wagner despised. Most piquantly, he produced an amusingly inappropriate Italianate ending for Lohengrin’s “Reprimand to Elsa” (the arioso, “Atmest du nicht mit mir die süssen Düfte?”) which sounds momentarily as if it might suddenly break into “Santa Lucia” (Example 5):

Example 4. Wagner/Liszt, “Song to the Evening Star,” from Tannhäuser, mm. 104—15.

Example 5. Wagner/Liszt, “Lohengrin’s Reprimand to Elsa,” mm. 58-63.

Liszt began to plow his own furrow more obviously toward the end of the 1850s. The “Fantasy on Themes from Rienzi” of 1859 is less of a transcription and more of an original work. Unusually for an opera fantasy, it is organized in sonata form, with the “second subject” (Rienzi’s battle cry, “Santo spirito, cavaliere”) in Liszt’s favorite major-third relation to the tonic—a feature of many of his symphonic poems.30 Liszt had a special reason for writing such an elaborate fantasy—an unexpected throwback to the more extended arrangements of his earlier years. Wagner had just been offered the prospect of a production at the Opéra in Paris, and planned to put on Tannhäuser. Liszt, however, was insistent that Rienzi was best suited to the tastes of the French public. He hoped that presenting Wagner with an advance piece of pianistic publicity would persuade him to take his advice. But Wagner would not budge. The well-known tale of the catastrophic Paris Tannhäuser tells us who was right.

Two subsequent excerpts from Der fliegende Holländer (“Spinning Chorus” and “Senta’s Ballad”) return to the more modest format of Liszt’s later transcriptions. They are not so much structurally as harmonically divergent from Wagner’s original, with the inclusion of languid Lisztian chromaticism quite alien to the world of the early operas.

Example 6. Wagner/Liszt, “Spinning Chorus” from Der fliegende Holländer, mm. 111-20.

If Isolde’s Liebestod is devoid of any additions after its new introduction, “Am stillen Herd” from Die Meistersinger shows the opposite approach. A floridly chromatic improvisation on the theme, it showcases a sequential development of motives extended even beyond that found in the opera. The Russian composer Alexander Borodin had personally heard Liszt experimenting in this style around the same period: “[Liszt] improvised new arrangements like Balakirev, sometimes altering the bass, sometimes the treble notes. By degrees there flowed from this improvisation one of those marvelous transcriptions in which the arrangement for piano surpasses that of the composition itself.”31

Had Wagner believed he had been “surpassed,” these later Liszt transcriptions would not have found much favor at Wahnfried. Yet Liszt played the Tristan and Meistersinger extracts to an enraptured Cosima in 1872, and occasionally extemporized other excerpts, such as “O sink hernieder Nacht der Liebe” from Tristan, before the master himself.32

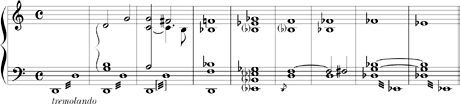

But toward the middle of the 1870s, a gradually deepening artistic gulf between Liszt and Wagner began to manifest itself in the transcriptions. This did not affect Liszt’s unbounded admiration for Wagner’s music, but it did affect Wagner’s opinion of Liszt’s. Some aesthetic aspects of the last Wagner arrangements constitute not just extempore extensions and embellishments of their source material but downright distortions. The beginnings of this can be seen in a third, radically revised version of the “Entry of the Guests” from Tannhäuser, made specifically at the request of Breitkopf & Härtel in 1876. Breitkopf, the publisher of Liszt’s 1853 and 1874 versions, had unexpectedly and preposterously been threatened with legal action by C. F. Meser, the original publisher of the Tannhäuser score. The latter alleged that Liszt’s transcriptions were so close to the vocal score as to constitute infringement of their copyright.

It must have been the first time that Liszt had been accused of undue fidelity in any walk of life, and he responded by casting aside all restraint in what at times constitutes a free fantasia rather than a transcription. The piece starts perfectly soberly with Wagner’s unadulterated introduction before the main theme suddenly turns up in the wrong key (D major instead of B major). Liszt then spends a wittily wandering page trying to get to the right one, producing what is effectively a development section before we have even heard the theme in the tonic. If one already knows Wagner’s march the effect raises a smile; if not, it can only seem utterly puzzling—exactly the sort of eccentricity without dramatic justification that Wagner so often railed against. He laid down the law a few years later: “Properly speaking, we cannot conceive of a chief motive of a symphonic movement as a piece of eccentric modulation, especially if it is to present itself in… a bewildering dress at its first appearance.”33 This arrangement remained unpublished in Liszt’s lifetime, and Wagner was probably never aware of its existence. The threat of legal action having presumably receded, it languished in Leipzig until 2002, when it was unearthed by the indefatigable editors of the New Liszt Edition.34

On the other hand, the even more outrageous Wagner/Liszt “Grail March from Parsifal” (1882) did reach the press the following year and was honored with a public premiere by none other than Liszt’s brilliant pupil Eugen d’Albert. This is indeed a peculiar piece—dragging Parsifal into the fragmentary, depressively willful world of Liszt’s late music. The themes are routinely “downsized”—broken up and repeated in circling sequences that never seem to have any particular tonal goal in view and rarely reach anything more than a halfhearted cadence. Wagner’s mysticism becomes Liszt’s pessimism.

It all sounds like a twisted parody of Parsifal rather than a transcription from it, as if Liszt is trying to remember the music but can’t quite figure out how it goes. And Wagner’s reaction? Surely this was one of the compositions he referred to in 1882 as evidence of Liszt’s “budding insanity.”35 The insanity reached full bloom soon afterward in Am Grabe Richard Wagners (At the grave of Richard Wagner), where further intensification of the tendencies shown in the “Grail March” reduce the entire piece to a disjointed, nostalgic sketch. Both works constitute a jarring compositional comment on the source material. Certainly not a condemnation—for their author remained the most steadfast of Wagner enthusiasts—but an unsettling reflection of Liszt’s own personal disillusion and disappointment.36

Example 7. Wagner/Liszt, “Grail March” from Parsifal, mm. 1-21.

And what of Wagner’s reaction to Liszt’s original music—before and after the “insanity” had taken its toll? Although the influence of Liszt on Wagner has been acknowledged as important by numerous writers, Wagner’s remarks on Liszt have mostly been ignored, as indeed has his influence on Liszt’s oeuvre. This is all the more strange in that Liszt’s encomiums for Wagner’s creative genius are cited ad nauseum, in fulfillment of his role in reception history as John the Baptist to Wagner’s Messiah. But Wagner’s own viewpoint is of compelling interest. He was better acquainted with Liszt’s output than most contemporary musicians, and brought to it a critical faculty capable of genuine insights when it was not being diverted by rants against Judaism, Catholicism, or theater directors. Wagner’s “borrowings” from Liszt’s music, too, are a type of criticism—a compelling musical commentary obscured neither by his bigotry nor his prose style. But as we shall see, ascertaining what these borrowings might actually constitute is hardly simple. Even what seems at first to be outright theft is sometimes only evidence of a striking artistic affinity.

Wagner’s opinion of Liszt’s music was as inconsistent as Liszt’s music itself was. Evaluating Wagner’s views is all the more delicate because most of his casual comments have come down to us through the agency of his second wife, Cosima, either in her own voluminous diaries or in Mein Leben, the autobiography dictated to her. Cosima, as Liszt’s daughter, was hardly a neutral interlocutor. Although Wagner seemed to be happy enough both to praise and criticize her father’s music in her presence, we might suspect that the frequent indignation expressed over the baleful influence of his companion Princess Wittgenstein (who had replaced Cosima’s mother, the Countess d’Agoult, in Liszt’s affections) may easily have been intensified in this context.

When Liszt and Wagner first forged an artistic alliance in the late 1840s Liszt was by far the more famous musician, but Wagner was already the more successful composer. As we have seen, Liszt’s eventual concentration on orchestral and choral music was decisively influenced by potential competition with Wagner, whereas Wagner’s initially grudging admission that after getting to know Liszt’s music he had become “ein ganz anderer Kerl als Harmoniker” (a completely different chap as a harmonist) is a standard line in the history books.37 In his old age, Wagner was more relaxed about things, reminding Liszt in 1878 that he had “stolen” much from the symphonic poems, joshingly calling them “un repaire des voleurs,” (a den of thieves).38 He had more chance than most to borrow ideas from Liszt’s music. The first set of six symphonic poems was published in 1856; the next six, with the Dante and Faust Symphonies, did not appear in print until a few years after. But Wagner had already been introduced to earlier versions of many of these works in 1853 when Liszt was his guest in Zurich. The laconic entry in Wagner’s “Brown Book” diary was only: “Liszt’s visit. Poetry. Symphonies.”39 Yet Wagner reminisced in his autobiography that he was given an extensive grand tour at the piano of Liszt’s latest music, likely including drafts of several symphonic poems (not just the first six) and certainly including sketches for the Faust Symphony.40 In a subsequent visit in 1856 Liszt brought with him a revised version of Faust and a draft of the Dante Symphony. The ensuing discussion is also detailed in Wagner’s My Life.41 So, although Wagner’s essay (or “open letter”) from 1857 “On Franz Liszt’s Symphonic Poems” is ostensibly a reaction to the final publication of some of the symphonic poems, he had been acquainted with the pieces in manuscript for some years. He had even heard Liszt conduct Orpheus and Les preludes in 1856 at a music festival in St. Gallen in which both composers participated.

One can rarely say for sure what constitutes direct theft from Liszt’s “den of thieves,” but the sheer number of possible cases is significant. The melody used for Sieglinde’s feverish nightmare in Act 2 of Die Walküre perhaps recalls the initial impact of Liszt playing through the Faust sketches to Wagner in 1853 (compare Examples 8a and 8b, on the following page).

Equally striking is the suggestive opening of Liszt’s wonderful song “Lorelei” (published 1856). It is so astonishingly similar to the start of Tristan und Isolde (begun December 1856) that the resemblance has drawn a bewildered gasp of recognition from at least one concert audience (Examples 9a and 9b).42

We might further speculate that the unusually consistent focus on the diminished seventh chord in the “Inferno” of the Dante Symphony inspired Wagner’s reliance on another, less strident seventh harmony—the famous “Tristan chord”—at significant points in his opera. This approach gives both works a distinct harmonic flavor, even if many critics have found the taste of the latter more palatable than the former. It has also been argued, intriguingly, that the open-ended harmonic and melodic construction of Orpheus was not without influence on the “endless melody” of Tristan und Isolde.43

On a more specific level, the bluff Kurwenal motive in the same opera sounds uncannily like a tune in Liszt’s largely forgotten Beethoven Cantata of 1845, while the theme for the “Wanderer” in Siegfried seems partly to have been inspired by a passage from Orpheus. Moreover, if Tristan begins with a salute to “Lorelei,” then the opera ends with an ecstatic climax distinctly recalling that of Liszt’s Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude, one of his favorite party pieces when playing the piano for friends (Examples 10a and 10b).44

Example 8a. Liszt, Faust Symphony, first movement, mm. 1-7 (piano solo arrangement by August Stradal).

Example 8b. Wagner, Die Walküre, Act 2, “Kehrte der Vater nun heim!”

Example 9a. Liszt, “Die Lorelei,” mm. 1-10.

Example 9b. Wagner, Tristan und Isolde, Prelude, mm. 1-7.

Example 10a. Liszt, Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude, mm. 294-301.

Example 10b. Wagner, Tristan und Isolde, Act 3, “Transfiguration” (“In des Welt-Atems wehendem All”), arr. Liszt.

But before we decide that the issue of Wagner’s artistic indebtedness to Liszt is an open-and-shut case—convincingly proven and brazenly admitted by the debtor himself—we should take a look at some contradictory evidence that certainly complicates matters. Particularly thought-provoking is the issue of the twin Fausts: Wagner’s Faust Overture and Liszt’s much more ambitious Faust Symphony. A glance at the opening of the Overture (Example 11) immediately reveals a remarkable similarity to the second theme (with the falling seventh) of the Symphony (Example 8a).

Example 11. Wagner, Eine Faust-Ouvertüre, mm. 1-6.

Is this yet another example of Wagner pillaging Liszt’s music? It would be easy to assume so, especially as the initially pensive atmosphere of both pieces is also virtually identical. But the chronology simply does not work. The first version of Wagner’s overture was written in 1840, and the initial sketches of Liszt’s Symphony seem to date from the middle of that decade.45 Could Liszt, then, have borrowed from Wagner? This too is unlikely, for Liszt did not get to know the overture until 1849, well after his first Faust sketches, when he requested a score from its composer with a view to performing the piece in Weimar.46 Liszt later told his student August Göllerich, “Wagner and I adopted the same theme for Faust before we even knew each other—I give you my word on this.”47 The melody with the falling seventh soon became one of Liszt’s favorite thematic shapes—variations of it appear in the Grosses Konzert-Solo (1849) as well as the later Sonata in B Minor. And we should not forget the additional influence of Berlioz (its dedicatee) on the Faust Symphony, which adds to an already tangled web. The beginning of the “Mephistopheles” movement is so close to the opening of the last movement of the Symphonie fantastique that Liszt must have intended it either as a friendly gesture of homage or a brazen plagiarism.

The explanation for all this is simply a certain affinity of musical styles between Liszt and Wagner. Both composers were, after all, quite capable of independent musical invention.48 This artistic intertwining becomes the more remarkable when we consider that in the 1840s Liszt already appears to have intended his Faust Symphony to comprise at least a “Faust” and a “Gretchen” movement, while Wagner’s Faust Overture was originally planned as the first movement, titled “Faust in Einsamkeit” (Lonely Faust), of a Faust Symphony of his own.49 The second movement of this was going to be—yes—“Gretchen.” Liszt, however, did not learn of Wagner’s abortive Faust Symphony scheme until late 1852, when Wagner mentioned it in a letter.50 If this were not enough, a revised version of Wagner’s Faust Overture was completed in 1854-55 at Liszt’s prompting, and very much with Liszt’s detailed advice in mind.51 Finally, the piano score of the Overture was arranged by none other than Liszt’s pupil, soon to be son-in-law, and eventually former son-in-law (owing to Wagner’s celebrated intervention): Hans von Bülow. A cozy compositional coterie indeed.

It can sometimes be difficult to say who the borrower and who the lender really is in this tangled musical web. To take another instance, Liszt’s song “Ich möchte hingehen” has often been pointed to as yet another prefiguring, like “Lorelei,” of the opening of Tristan und Isolde. In this case even the “Tristan chord” itself appears. But as with the Faust Overture, chronology throws a spanner in the works. The anticipation of Tristan turns out to be a quote from it—Liszt added the relevant bar after he got to know Act 1 of the opera.52 And even when a direct Wagner borrowing seems fairly likely, as in the Orpheus-Siegfried similarities, Liszt’s ideas tend to be treated with a new sophistication in Wagner’s hands.53 The latter’s version of the Orpheus passage is less four-square, less repetitive, more contrapuntal (Liszt’s elegant melodic melisma appears to have been transformed into Wagner’s inner part writing in the second bar). We note a striving after a longer line, and a greater richness of texture. Now, it is quite true that complexity is not always more satisfying than simplicity (otherwise Reger and Sorabjii would be among the twentieth century’s most lauded composers), but Wagner seems to know where to stop—how to keep on the right side of satiety.

Many other fascinating instances of this type of transformed borrowing could be cited, capped with one specific resemblance admitted by Wagner himself—that of the opening theme of Parsifal’s Act 1 prelude to the “Excelsior” prelude of Liszt’s cantata The Bells of Strasbourg Cathedral.54 The copious use of bells in Liszt’s cantata certainly inspired a similar sound-world in Parsifal. Cosima even noted that in 1879, when drafting the Act 1 “Grail March” (probably the transformation music and its continuation), Wagner refreshed his memory of Liszt’s score “to make sure that he has not committed a plagiarism” (CWD, 28 December 1877). Or too much of a plagiarism, at any rate. Both pieces are pervaded by thematic fragments based on familiar patterns of bell chimes, even if Wagner’s tintinnabulations were ultimately different in outline and much lower in pitch than Liszt’s. But let us return for a moment to the famous borrowed theme:

Example 12a. Liszt, Excelsior, mm. 1-8.

Example 12b. Wagner, Parsifal, Act 1, Prelude, mm. 1-6.

Liszt’s music seems like a mere skeleton of Wagner’s, for the latter spins out melodic lines of vastly greater length and subtlety. Yet however short-breathed and sketchy Liszt’s phrases are here, they obviously contain the germ of the Parsifal idea. We might also ask if the opening of “Purgatio” from the Dante Symphony had a further influence on Wagner’s continuation. Liszt presents his material in the symphony just as Wagner was later to do in the opera, in separate, transposed blocks, each ending with ethereally arpeggiated chords floating like the perfume of incense up into the higher reaches of the orchestra.55 Again, Wagner does something more with the material. The Liszt version is beautiful but static—a very pretty picture in which nothing much is actually going on.56 Wagner’s harmony has, on the contrary, both variety and forward motion. With the transposition to C minor, the music unexpectedly takes on a newly piercing poignancy, suggesting a film narrative rather than a photo.

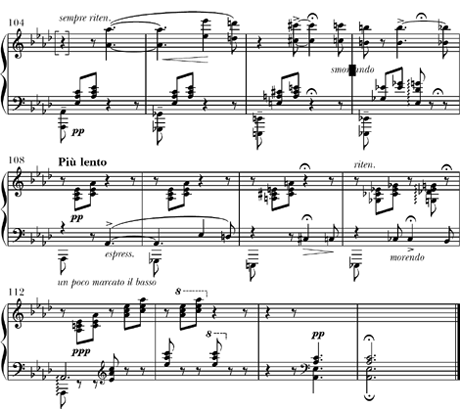

Thus it is especially ironic that it should have been Liszt’s transcription from Parsifal that most jarringly illustrated just how far his own musical world had moved from Wagner’s by the early 1880s—a divergent path that was trod further in the poignantly brief Am Grabe Richard Wagners. This nostalgic eulogy for Wagner incarnates the interaction between the two men both in the music and in Liszt’s written preface to the score: “Wagner once reminded me of the similarity between his Parsifal motive and a theme in my previously written ‘Excelsior’ (the Introduction to the Bells of Strasbourg). May this resemblance be enshrined here. He has fulfilled all that is great and noble in the art of the present day.” The composer of Parsifal would probably have hated the bizarrely meandering melodic distortions in this shadowy sketch. It twists the theme back into an exhausted echo of Liszt’s cantata, then stumbles fitfully heavenward, blindly searching for the “grail motive” that opened Lohengrin.57 Failing, it descends exhausted to more earthbound regions with a gentle chiming of Parsifal bells. But Wagner was now in no position to complain.

Example 13. Liszt, Am Grabe Richard Wagners, mm. 1-24; continued on next page.

Example 13. Liszt, Am Grabe Richard Wagners, mm. 25 - conclusion.

Naturally enough, Wagner’s celebratory “open letter” to a pointlessly mysterious MW (Marie Wittgenstein, Princess Carolyne’s daughter) “On Franz Liszt’s Symphonic Poems” (1857) mentions nothing of any musical borrowings.58 Such admissions were not for public consumption. Indeed, the essay is couched in unusually vague terms, even taking into consideration Wagner’s typically tortuous writing style. His private evaluation of Liszt’s music was more direct, more mixed and frequently more thought-provoking. Nevertheless, one thing that shines through the pretentious fog of Wagner’s prose is his enormous admiration for Liszt’s artistic personality. Like Hanslick, he was never in doubt that Liszt was a “great man.” His enthusiastic response to Liszt’s Sonata in B Minor was effectively based on this—that the music reflected the personality of its creator—“Dearest Franz, you were suddenly with me!”59 Later on, Liszt’s artistic personality seemed to be shaped by forms other than the sonata—but always with the obligatory “apotheosis.” Privately, Wagner waxed poetic to Cosima:

Your father’s life course is stated for me in the “variation.” One has before one nothing except the theme, repeated ever anew, but always somewhat altered, adorned, decorated, in different clothes, now virtuoso, now diplomat, now martial, now spiritual, always amiable, always himself, at bottom incomparable and for that reason presented to the world only in variation form; personality ever to the fore, noticeable above all, always so placed that the latter is shown to advantage, as under a prism—ever unique, repeatedly astonishing, but always the same, and—following each variation, it goes without saying, applause. Then comes the peroration, the apotheosis—the coda of the variations.60

Whatever the success of individual Liszt pieces, then, they luckily partook of the fascination of Liszt’s personality. “It is all interesting, even when it is insignificant,” Wagner declared (CWD, 30 November 1872). Nevertheless, his fascination with Liszt’s compositions was tempered by intermittent reservations. One of his bugbears was Liszt’s fondness for clamorous conclusions—what Wagner described as his Apotheosen-Marotte or “apotheosis obsession,” a feature of Les preludes and Tasso: Lamento e trionfo among many other works (CWD, 2 August 1869).

Accordingly, Wagner preferred the slightly more restrained orchestral ending of the Faust Symphony without the chorus, and had little time for the alternate fortissimo peroration of the Dante Symphony.61 Wagner’s shadow fell over the latter work particularly strongly (he was to be its dedicatee). Liszt’s original plan had been to compose a three-movement symphony, Inferno-Purgatorio-Paradiso, following the ground plan of Dante’s Divine Comedy. The last movement was to include a chorus. But Wagner argued him out of this—he felt that the Paradiso part of Dante’s poem was by far the weakest section. It certainly wasn’t Wagner’s idea of a good time: after the trials of Hell and Purgatory, Dante’s Paradise turns out to involve endless discussions of theology (whereas Wagner’s favorite pink silk underwear is nowhere even mentioned). An effective representation of Paradise in music, Wagner insisted, was impossible, and he counseled Liszt to abandon plans for an elaborate choral finale.62 His advice was followed. As published, the symphony includes only movements depicting hell and purgatory, the latter finishing with a fairly short choral passage intoning the Magnificat. But Liszt still provided alternate endings in the score of the Symphony—the one fading away mystically, the other concluding clamorously—an apotheosis yet again.

The inclusion of these histrionic farewells, Wagner had no doubt, was due to the malign influence of the Princess Wittgenstein. She “understood only the crudest effects.”63 As early as 1849, before he had heard a note of Liszt’s orchestral music, Wagner had inveighed against the “brainless herd of imitators” of Beethoven’s C-Minor Symphony. Their music charted a clichéd course from misery in the minor key to martial triumphs in the major.64 Liszt may not have been brainless, but he was certainly fond of swaggering codas. He even added an “apotheosis” to Die Ideale when one was, regrettably, not to be found in the source poem by Schiller. It is not surprising that out of all Liszt’s compositions, Wagner reserved “a special place of honor” for the delicate and restrained symphonic poem Orpheus, although he could not deny the “great drive” of Mazeppa, even if it did end with a bang (his admiration for Mazeppa is enshrined in the wonderful “Ride of the Valkyries”).65 Unfortunately, many of Liszt’s other orchestral works also feature the hysterical endings Wagner hated, and Princess Wittgenstein certainly cannot be blamed for them all. Tasso: Lamento e trionfo is even in C minor/major, marred by a load of “triangles, gong-strokes and rattling of chains”—this from the man who wrote for sixteen anvils in Das Rheingold.66

Noticeably, an “apotheosis obsession” is not mentioned in Wagner’s essay on Liszt’s symphonic poems, despite it being a prominent trait of five out of the six pieces under discussion. But in the context of his apologia, Wagner does not hesitate to catalog other common contemporary criticisms of Liszt’s music: its rambling “formlessness” and eccentric harmonic effects, typically viewed as the result of a misguided attempt by a great performer also to be a great composer. He certainly chooses a surprisingly roundabout way of rebutting these criticisms. To claim, as he does, that Liszt’s piano playing constitutes “genuine production, rather than just reproduction,” is rather beside the point, since the inspiration of the playing was never an issue, only the compositions. Moreover, Wagner’s assertion that Liszt’s music has a “form” derived from the “poetic idea” remains nothing more than an assertion. Although he condemns Beethoven for writing a too-conventional recapitulation in the third Leonore Overture, and criticizes Berlioz for “losing the thread” in the Adagio movement from Roméo et Juliette, he never seems to want to go into details about exactly how Liszt does things better. Perhaps he is referring to the much freer treatment of recapitulation in Tasso and Orpheus, but if he is, why does he not simply say so? Wagner does at least directly rebut complaints about Liszt’s willful treatment of harmony, and openly praises the “pregnancy of the themes.”67

In private, Wagner’s evaluation of Liszt was at times more directly critical, but at least less opaque. He lauded the Faust Symphony, especially the “masterly conception of the Mephisto movement” (CWD, 23 May 1882), and admired the “musical scene painting” of the Dante Symphony (CWD, 27 August 1878), even if it required listeners to know too much about Dante’s poem for easy accessibility (CWD, 22 September 1880). Anyway, the Dante Symphony was just too Catholic for Wagner’s taste, as indeed was Christus, where “the resources of a great and noble art” were used to “imitate the wailing of priests” (CWD, 7 June 1872). Almost needless to say, the fanatical Catholicism of Princess Wittgenstein was blamed for this, too. When the Wagners attended a Weimar performance of Christus, conducted by the composer, their reaction ranged from “ravishment to immense indignation,” although the conducting was pronounced to be excellent. Liszt was, alas, “the last great victim of this Latin-Roman world” (CWD, 29 May 1873). A performance of Christus with full orchestral and choral complement at least allowed it a fair hearing. On receiving the vocal score of the oratorio, Wagner had stumbled through it on the piano, criticizing along the way the clumsy choral writing (CWD, 7 June 1872). The clumsiness, however, may have lain elsewhere. When Liszt played over the score, it suddenly sounded much better. Cosima ingenuously remarked, “It certainly seemed very different under his fingers” (CWD, 16 October 1872).

However tendentious Wagner’s evaluation of Christus—later he would speak more highly of it when it gave him a corresponding chance to condemn Brahms’s Triumphlied (CWD, 8 August 1874)—he unerringly identified one significant feature of Liszt’s musical makeup that is underrated today, namely his fondness for French grand opera. The oratorio was indeed, as Wagner asserted, “thoroughly un-German” in its blend of “Old Church style” with echoes of Meyerbeer and Halévy, whose operas had “a decisive influence” on Liszt in his youth (CWD, 9 June 1872). (Undeniably, they had just as strong an effect on Wagner.) Even today, many find the stylistically Catholic cosmopolitanism of Liszt’s music difficult to swallow, and although Wagner himself did not make the connection, French grand opera likely shared some responsibility for Liszt’s apotheosis obsession. The more pompous passages of Les preludes could easily be inserted into the “Blessing of the Daggers” scene of Les Huguenots and hardly an eyebrow would be raised.

Eclecticism and extroverted conclusions were simply part of Liszt’s middle-period musical style, whether one warmed to it or not. But technical failings were quite another matter. Wagner could not ignore the odd lapses in concentration that marred even fine works such as the Faust Symphony. Here he was surprised to find scrappy inner-part writing, in contrast to his own care over such things.68 Liszt thought no one bothered listening to the inner voices, claimed Wagner. He might also have pointed out that Liszt’s music generally shies away from contrapuntal complexity—the melodies are memorable, the harmonies often novel, but the texture tends to be “tune with accompaniment” (see discussion of Orpheus/Siegfried above), even in supposedly fugal passages. Moreover, a startling unevenness, as Wagner noted, is disconcertingly evident not only within but between pieces. A Liszt rhapsody might be “original … and reflect [the composer’s] individuality” (CWD, 10 October 1882)—the “great personality” once more makes its bow—whereas the symphonic poem Hamlet gave Wagner the impression of “a disheveled tomcat lying there before him.”69 The revised Beethoven Cantata of 1870 was supposedly even worse—impossible to appreciate owing to the text, its treatment, and indeed the entire genre to which it belonged. Worst of all, the main theme of the Eroica Symphony was sung! (CWD, 30 June 1870)

The most trenchant criticism reported in Cosima’s diaries, however, was reserved for Liszt’s late music. Admittedly, Wagner still seemed to be able to enjoy Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este and Aux cyprès de la Villa d’Este from the third Année de pelerinage.70 He was also mightily amused at the sudden moderation of Liszt’s technical demands. “Now I too am a Liszt pianist!” he proclaimed, gleefully pointing out a resemblance between the main tune of Zum Andenken Petöfys and Brünnhilde’s “War es so niedrig” from Walküre, Act 3 (CWD, 8 July 1879). But the Second Mephisto Waltz of 1881 was resolutely trashed (a “dismal production,” CWD, 2 March 1882), as was the Christmas Tree Suite.71 One evening he announced (“sharply, and in much detail”) that Liszt’s latest efforts were “completely meaningless” (CWD, 28 November 1882). Cosima made a mental note to consider writing to her father, in the hope that Wagner’s verdict might bring him to his senses, as it were. Yet her husband had not quite exhausted his interest in the topic. The next night he pursued his quarry further, unleashing a frothing tirade of abuse against Liszt’s recent music.72 The Wagner children seem to have found his choice of words a bit too near the bone. They were, after all, also Liszt’s grandchildren, and Daniela was no doubt proud to be the dedicatee of the condemned Christmas Tree Suite.73 Part of the relevant passage in Cosima’s diary was energetically obliterated. Enough remains to read the words keimender Wahnsinn (sprouting insanity) and a final verdict: “It is impossible to develop a taste for these dissonances.”

Was it Liszt’s transcription of the “Grail March” from Parsifal that broke the camel’s back? It certainly could also have been a number of other radical experiments, like the bizarre Csardas macabre, whose manuscript bears the inscription “May one write or listen to such a thing?” But Parsifal lay closer to Wagner’s heart. He might have been able to endure “without comment” the bleak fragmentation creeping into Liszt’s original music, but not when the style was applied to his own operas. Wagner’s music had retained the long lines, the generous elaboration that Liszt’s only sporadically attained and had now completely abandoned. Perhaps Liszt’s futuristic fragments arose as much from failing powers of concentration as from disappointment with life, but whatever their catalyst, they were utterly alien to Wagner’s musical aesthetic. Cosima was taken aback by the intensity of her husband’s tirade, remaining “silent, sad,” uncertain how to reply. But she could have said that Liszt’s creative approach had remained consistent. The new music was as expressive of his current personality as the confident cosmopolitanism of his Weimar years had been. It was simply now the music of a different man—a man who had suffered one setback too many. Liszt’s grand apotheosis obsession had finally burned itself out, but Wagner was still living through his own personal apotheosis. The years of artistic affinity had passed.

1. There are many eyewitness accounts of Wagner’s tribute to Liszt at the 1876 Bayreuth Festival; see, for example, Berthold Kellermann, Erinnerungen: Ein Künstlerleben (Zurich, 1932), 193-95. For Liszt’s last days and the “Tristan!” story, see Alan Walker, The Death of Franz Liszt: Based on the Unpublished Diary of his Pupil Lina Schmalhausen (Ithaca, N.Y., 2002), 3. Wagner once remarked to Cosima that had it not been for her father, his works would possibly be “moldering beside Reissiger and his Schiffbruch der Medusa,” referring to one of the largely still-born operatic efforts of his former Dresden colleague Karl Gottlieb Reissiger. Cosima Wagner’s Diaries, ed. Martin Gregor-Dellin and Dietrich Mack, trans. Geoffrey Skelton, 2 vols. (New York and London, 1978, 1980), 2:42 (entry of 16 March 1878). Subsequent references to the Diaries in the main text and endnotes are given as CWD, with the date of entry.

2. Liszt had officially been Kapellmeister im außerordentlichen Dienst (Kapellmeister Extraordinary) since 1842, but this committed him to spend only three months a year in the small German town of Weimar. Before 1848 he rarely got around to fulfilling even this less than onerous attendance requirement.

3. Robert Schumann, Music and Musicians, trans. F. R. Ritter (London, 1878), 1:351. Ironically, some critics could have made the same complaint about Schumann—who started as a composer much later than Liszt—and indeed some did. Such an evaluation lies at the heart of Hans von Bülow’s description of Schumann as a “sentimental” composer—one who actively struggled in his mature years for compositional mastery—as opposed to the “naïve,” precociously talented Mendelssohn. Bülow was evidently adopting Schiller’s famous distinction between “naïve” and “sentimental” poetry.

4. For a full account, see Kenneth Hamilton, “Not with a Bang but a Whimper: The Death of Liszt’s Sardanapale,” Cambridge Opera Journal 8/1 (1996): 45-58.

5. Adrian Williams, Franz Liszt: Selected Letters (Oxford, 1998), 238. It has been customary for scholars to claim that the Petrarch Sonnets were first written in 1838-39. See, for example, Humphrey Searle, The Music of Liszt (New York, 1966), 31. In this letter of 1846, however, Liszt acknowledges them as brand-new works. According to Rena Mueller (“The Lieder of Liszt,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Lied, ed. James Parsons [Cambridge, 2004], 170-1) the melodies (without words) first appear in a sketchbook around 1843-44.

6. La Mara, ed., Franz Liszts Briefe, 8 vols. (Leipzig, 1893-1905), 1:287.

7. Ibid., 8:62

8. Hanjo Kesting, ed., Franz Liszt-Richard Wagner Briefwechsel (Frankfurt am Main, 1988), 162.

9. Ibid., 161-62. (All translations of the Liszt-Wagner correspondence are mine.) Welsch is the word that Hans Sachs notoriously uses toward the end of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger with reference to the foreign (implicitly Franco-Italian) artistic influences threatening German culture.

10. Ibid., 163.

11. The appearance of Raff’s opera was accompanied by the obligatory Liszt transcriptions for piano—in this case the Andante Finale and March. The former is an attractive and perhaps unjustly forgotten piece, which obviously owes a lot to Liszt’s own “Cantique d’amour” from Harmonies poetiques et réligieuses. The latter piece is, alas, justly forgotten.

12. Kesting, Liszt-Wagner Briefwechsel, 180.

13. See Monika Hennemann, “Mendelssohn’s Dramatic Compositions: From Liederspiel to Lorelei,” in The Cambridge Companion to Mendelssohn, ed. Peter Mercer Taylor (Cambridge, 2004), 206-32.

14. Kesting, Liszt-Wagner Briefwechsel, 187. The Deutsche Monatsschrift extracts were slightly revised by Wagner, and therefore the text differs somewhat from that of Oper und Drama.

15. Liszt toyed with a handful of other operatic plans in later years, but none of them came anywhere near fruition.

16. Kesting, Liszt-Wagner Briefwechsel, 248.

17. Letter from Liszt to Franz Brendel, 8 November 1862, in La Mara, Letters of Franz Liszt, trans. Constance Bache (London, 1894), 2:33. One can’t help feeling that Liszt’s routine tendency to “problematize” things would have ensured him a solid career in twentieth-century musicology.

18. Liszt’s opera transcriptions were published under a profusion of titles: the Tannhäuser Overture, for example, was a “Concert Paraphrase,” and most other pieces appeared as “arrangements” (Bearbeitungen). For Rienzi Liszt produced a “fantasy piece” (Fantasiestück).

19. “Über Franz Liszts Symphonischen Dichtungen” (1857), in Richard Wagner, Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen (henceforth GSD), 10 vols. (Leipzig, 1887-1911), 5:193-94.

20. David Garrick’s eighteenth-century performing text of Romeo and Juliet was still as commonly performed in the early nineteenth century as it is ignored in ours. It was accordingly the Garrick reworking that Berlioz first saw on stage. The difference in quality between Garrick’s and Shakespeare’s versification would hardly have been evident to anyone with as little knowledge of English as Berlioz.

21. Translated from “Über die Anwendung der Musik auf das Drama” (1879) by William Ashton Ellis, in Richard Wagner’s Prose Works, 8 vols. (London, 1895-99), 6:189-90.

22. Eduard Hanslick, Aus dem Tagebuch eines Rezensenten, ed. Peter Wapnewski (Kassel, 1989), 13 (my translation).

23. Letter of 23 November 1876 to Breitkopf & Härtel, in La Mara, Letters of Franz Liszt, 2:307. Several of the early transcriptions from Tannhäuser and Lohengrin were subsequently revised (sometimes more than once), resulting in a sequence of published editions with minor pianistic differences.

24. For the practice of piano preluding in the nineteenth century, see Kenneth Hamilton, After the Golden Age: Romantic Pianism and Modern Performance (New York, 2008), 101-38. The manuscript of Liszt’s transcription of “Isolde’s Liebestod” partially survives in the Goethe-und Schiller-Archiv, Weimar (MS. U32). It was Liszt, incidentally, who was largely responsible for the subsequently familiar attribution of this name (Liebestod) to the final episode of the opera, which Wagner had referred to as Isolde’s Verklärung (“Transfiguration”). He himself applied the term “love death” (Liebestod) to the Act 1 Prelude.

25. Richard Wagner, My Life, trans. Andrew Gray and Mary Whittal (Cambridge, 1983), 270. Liszt’s published “Fantasy on Themes from Rienzi,” S.439, dates from 1859.

26. For the amateur: Wolfram’s “Song to the Evening Star,” or “O, du mein holder Abendstern,” from Tannhäuser; “Elsa’s Dream,” “Elsa’s Procession to the Minster,” and “Lohengrin’s Reprimand to Elsa,” from Lohengrin. For the virtuoso: Tannhäuser Overture and “Entry of the Guests at the Wartburg”; Act 3 Prelude and “Bridal Chorus” from Lohengrin.

27. Liszt’s letter of 26 February 1849 and Wagner’s of 1 March 1849 in Kesting, Liszt-Wagner Briefwechsel.

28. Listening to a performance of Liszt’s arrangement of the overture, Wagner admitted to having been influenced by some figuration in the first movement of Berlioz’s Harold in Italy (CWD, 14 January 1882).

29. Kesting, Liszt-Wagner Briefwechsel, 274.

30. There are also hints of sonata form in Liszt’s juvenile Impromptu on Themes of Rossini and Spontini, and in his much later arrangement of the Waltz from Gounod’s Faust.

31. A. Habets, Borodin and Liszt (London, 1895), 141.

32. CWD, 20 October 1872. Cosima refers to “the A-flat music from Tristan,” which surely means “O sink hernieder.” Liszt, of course, never published a transcription of this section.

33. From “On the Application of Music to the Drama,” in Ellis, Richard Wagner’s Prose Works, 6:189.

34. New Liszt Edition, series 2, vol. 10 (Budapest, 2002), ed. László Martos and Imre Sulyok. The manuscript of Liszt’s additions is presently housed in the Sächsische Staatsarchiv in Leipzig.

35. “Today he begins to talk about my father again, very blunt in his truthfulness; he describes his new works as ‘budding insanity’ and finds it impossible to develop a taste for their dissonances” (CWD, 29 November 1882). The editors note that “about twelve words” in the latter part of the sentence were obliterated in the manuscript of the diaries.

36. The only hint I can find of criticism of Wagner’s later music by Liszt is in the Russian composer (and member of the so-called Kuchka) Cesar Cui’s reminiscences of a chat with Liszt: “Later, over tea I told him what I thought of Wagner, the falseness of his system, the insignificant role he assigns to the voice, the melodic poverty resulting from his monotonous reiteration of themes, and so on. The Baroness [von Meyendorff] listened with horror, Liszt—with a slight smile. “Il y a du vrai dans ce que vous dites là, mais, je vous en supplie, n’allez pas le répéter à Bayreuth!” (There’s some truth in what you say, but I beg you, don’t go around Bayreuth repeating it!) Vladimir Stasov, Liszt, Schumann and Berlioz in Russia (St Petersburg, 1896), in Vladimir Stasov: Selected Essays on Music, trans. F. Jonas (New York, 1968), 183.

37. Richard Pohl’s “indiscreet” article mentioning Liszt’s harmonic influence on Wagner appeared in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in four installments, from 17 to 19 August 1859, at the height of the critical debates over the so-called music of the future. The article is reprinted in Richard Pohl, Richard Wagner: Studien und Kritiken (Leipzig, 1883). For Wagner’s reaction (in a letter to Hans von Bülow), see Richard Wagner: Sämtliche Briefe, ed. Martin Dürrer (Wiesbaden, 1999), 11:282.

38. CWD, 27, 29 August 1878. Wagner’s expression seems rather ill-chosen here—after all, he is the one admitting stealing from Liszt, so the symphonic poems are more a target for thieves than a den of them. But one cannot really expect constant vigilance over linguistic accuracy in casual conversation.

39. Joachim Bergfeld, ed., The Diary of Richard Wagner, 1865—1882: The Brown Book, trans. George Bird (London, 1980), 102-3.

40. Wagner, My Life, 495.

41. Ibid., 537-38.

42. At the Bard College Liszt and His World Festival in 2006. Not surprisingly, “Lorelei” was one of Wagner’s favorite Liszt pieces (see, for just one example, CWD, 30 November 1872).

43. See Rainer Kleinertz, “Liszt, Wagner, and Unfolding Form,” in Franz Liszt and His World, ed. Christopher Gibbs and Dana Gooley (Princeton, N.J., 2006), 231-54.

44. With a preceding page of surging harmonic sequences possibly inspired by, of all things, “Padre, tu piange?” from Bellini’s Norma. But then, Wagner was a big Bellini fan before he transformed himself into the savior of German opera.

45. Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, Weimar, MS. N4, a sketchbook from the mid-1840s. An undated separate page of sketches (probably from later in the decade) is the first to show the opening of the symphony in a form that we can recognize as similar to the final version, with the juxtaposition of the two principal themes. See Laszlo Somfai, “Die Musikalische Gestaltwandlungen der ‘Faust-Symphonie’ von Liszt,” in Studia Musicologica 2 (1962): 87-137, esp. 100 and 113.

46. Kesting, Liszt-Wagner Briefwechsel, 60. Of course, if the page mentioned in above n. 45 turns out to date from after Liszt got to know the Faust Overture, the issue of a direct influence from Wagner may have to be nuanced yet again. The situation is somewhat complicated here by Wagner’s misdating of his 30 January 1849 letter to Liszt assenting to the dispatch of the Faust Overture score. As is so easy to do early in a new year, he absent-mindedly scribbled “1848.” Both the context and the subsequent course of the correspondence make it clear that 1849 is correct, an interpretation usually adopted by modern editors of Wagner’s letters.

47. August Göllerich, Franz Liszt (Berlin, 1908), 172.

48. The search for borrowings can easily reach obsessive levels, as if music were written on the basis of Tom Lehrer’s song “I Got It From Agnes …” (“And just because we really care/Whatever we get, we share!”).

49. See Somfai, “Die musikalische Gestaltwandlungen der ‘Faust-Symphonie’ von Liszt,” 100. Although in the initial (1840s) sketches for the Faust Symphony the first movement is fairly thoroughly drafted, Liszt had devised little more than a melody for “Gretchen.” The final “Mephistopheles” movement is notable by its complete absence, although it seems probable that Liszt intended even at this point to complete the work with this.

50. Kesting, Liszt-Wagner Briefwechsel, 248.

51. The fascinating exchange of views over the revision of the Faust Overture will be found in ibid., 241, 248, 254, and 398. Liszt suggested, among other things, a revision of the orchestration—especially the use of the brass section, which he found too overpowering—and an expansion of the second-subject group, including the addition of a new, tender, Gretchen-like theme. Wagner followed most of this advice, reworking the orchestration and lengthening the second key area. He did not, however, add the recommended new theme, on the grounds that this would effectively force him to write an entirely new piece.

52. One can trace the thread of inspiration beyond “Lorelei,” Tristan and “Ich möchte hingehen,” to end up at Liszt’s late Aux cyprès de la Villa d’Este no. 2, in which a variant of the “Lorelei”/Tristan opening phrase again raises its familiar head.

53. One might, however, wish to nuance Charles Rosen’s verdict that the resemblance between the openings of “Lorelei” and Tristan “is not entirely to Liszt’s credit, as Wagner’s reworking is both more interesting and more powerful.” Rosen, The Romantic Generation (Cambridge, Mass., 1995), 475. Rosen’s view is partly based on what he considers (correctly, in my opinion) to be Liszt’s routine overuse of harmonies based on the chord of the diminished seventh. Wagner’s rewriting of the “Lorelei” opening is indeed more novel harmonically, but Liszt’s employment of the hollow-sounding, directionless diminished seventh is perfectly suited to the mood (puzzlement, rather than yearning) of the words he intends to illustrate (“Ich weiß nicht, was soll’s bedeuten”). This is immediately obvious if we try recomposing Liszt’s introduction using Wagner’s harmonies.

54. For the full story, see the account by Liszt’s student and amanuensis August Göllerich in his Franz Liszt, 22-23. (Liszt pointed out that he did not invent the Excelsior melody—it was based on a Catholic Church chant.) One might also speculate that the “dragging” motive of Amfortas in Parsifal was influenced by the opening of Liszt’s Vallée d’Obermann, or even Wotan’s “spear” motive in the Ring by the similarly commanding descending-scale theme in Liszt’s B-minor Sonata. The prelude to Act 1 of Die Walküre, too, unfolds in a surprisingly static, Lisztian fashion—what Gerald Abraham (One Hundred Years of Music [London, 1974], 40-41) memorably called Liszt’s “wallpaper-pattern” style of construction—and the sinuous chromaticism of Brünnhilde’s “Magic Sleep” in Act 3 of the same opera strongly recalls Mephistopheles’ final disappearance in the third movement of the Faust Symphony.

55. This cyclopean style of construction is probably partly inspired by the opening of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and perhaps also by the development section in the first movement of his Sixth. Liszt had another go at rewriting the beginning of Beethoven’s Ninth in the Kyrie of his Gran Mass.

56. We know from Liszt’s associate Richard Pohl what this picture is actually intended to be. In a (gushingly sycophantic) “Einleitung zu Liszts Dante-Symphonie” (printed by Breitkopf & Härtel as the preface to August Stradal’s piano solo transcription of the score) we are told that it illustrates the passage in Dante’s poem where the travelers emerge from hell, enchanted by the sight of the rising sun from their gently undulating boat.

57. Am Grabe Richard Wagners exists in two versions: for piano and for string quartet and harp. The Lohengrin allusion—a reminiscence of the high string sonorities at the start of the opera—naturally appears more immediate in the string/harp scoring. Liszt also wrote a short funereal piece in memory of Wagner titled RW-Venezia, and a reworked version of his La lugubre gondola (the first sketch of which was written during a stay with the Wagners in Venice, shortly before Wagner’s death) was published in the year of Liszt’s death with a title page depicting Wagner’s grave. Liszt had come to consider the piece as a musical prophecy of Wagner’s demise.

58. Wagner, GSD, 5:182-98. The original, rather different manuscript version of this “open letter” can be found in Wagner, Sämtliche Briefe, 8:265-81. None of these differences, however, significantly affect the broad thrust of the argument.

59. Kesting, Liszt-Wagner Briefwechsel, 417.

60. Bergfeld, ed., The Diary of Richard Wagner, 72 (entry of 10 September 1865, addressed to Cosima).

61. Wagner, My Life, 537-38. The Faust Symphony originally ended with a fairly short orchestral coda. Later Liszt had the idea of appending a setting for solo tenor and male voices of the Chorus Mysticus from Faust, Part II. Wagner’s memory was at fault when he implied in My Life that the orchestral ending faded away quietly (“ended delicately and sweetly with a last, utterly compelling reminiscence of Gretchen, without any attempt to arouse attention forcibly”). Pace Wagner, it, too, forms a loud, grandiloquent close, but certainly one less hyperbolic than the choral version.

62. Wagner and Liszt’s discussion of the form of the Dante Symphony can be found in Kesting, Liszt-Wagner Briefwechsel, 423, 425-27, 431, 436.