Composers who distrusted and shunned each other in the light of day often come together in secret: Wagner and Offenbach in the crimson salon of a God-forsaken love.

— Theodor Adorno, Quasi una fantasia

If one understands by artistic genius the greatest freedom under the law, divine frivolity, facility in the hardest things, then Offenbach has even more right to the name “genius” than Wagner…. But perhaps one might understand something else by the word genius.

— Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power

Everything that recalls the modern immorality of Parisian life, everything that might encourage its cultivation in our land we will seek to destroy…. Offenbach out of Germany!

— Alfred Dörffel, “Aus neuester Zeit”

(Musikalisches Wochenblatt, 23 September 1870)

In the seclusion of his Swiss villa Tribschen on the shores of Lake Lucerne, Richard Wagner enjoyed the Franco-Prussian War immensely. Of course, the war against France aroused patriotic, not to say chauvinistic enthusiasm in Germans of all stripes, Brahms no less than the young Friedrich Nietzsche, for instance. Especially following the strategic defeats of the French at Sedan, Strasbourg, and Metz in the late summer and autumn of 1870, German support for the war was vigorous and nearly universal. For Wagner, however, it was a personal as well as a national affair: the Prussian-led campaign against the French Second Empire was nothing less than a vindication of the deprivations and humiliations inflicted on him by a heartless and soulless Paris during his failed attempt to achieve international recognition there in 1839-42, the Parisian Tannhäuser fiasco of 1861, and several brief, equally troubled encounters in between. If the protracted siege of Paris following the military defeat at Sedan was for Bismarck a political tactic to force diplomatic cooperation from the unstable government replacing Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III), a tactic which he to some extent regretted, Wagner experienced the siege as an act of personal vengeance conveniently staged for him by the armies of the federated German states. He was also very willing to take spiritual credit for the success of the German armies. When his infant son Siegfried was christened on September 4, 1870 (the day on which a provisional republican “Government of National Defense” was declared after the fall of Sedan and the capture of the emperor), Wagner declared proudly, “I am bad for the Napoleons! When I was six months old there was the Battle of Leipzig, and now Fidi is hacking up the whole of France.”1

Cosima Wagner’s diaries provide a running commentary on the entire course of the conflict, from July 1870 to the final capitulation of Paris in late January 1871. They also provide the background to a small literary jeu d’esprit (or mauvais esprit) that occupied Wagner briefly toward the end of the fall, when the Germans continued to fight the armies of the new French government and to maintain their strategic blockade of the French capital. As a diversion from work on Siegfried and the tone poem Siegfried Idyll (being written secretly as a birthday surprise for Cosima), he drafted a topical and tasteless farce on the wartime dilemma of the French titled Eine Kapitulation and designated “ein Lustspiel in antiker Manier” (a comedy in the manner of the ancients). The inspiration for this piece of self-entertainment was a celebrated episode that occurred a month after the founding of the provisional government, when the charismatic one-eyed republican leader Léon Gambetta—at first appointed Minister of the Interior, afterward of Defense—journeyed by hot-air balloon from a beleaguered Paris to the vicinity of Tours in order to energize political and military support and to establish an alternative provincial seat for the new government.2 (This adventurous mode of air transport, along with the extensive use of carrier pigeons, became an emblematic image of the siege, as shown in the 1870 painting by Puvis de Chavannes, The Balloon: The Besieged City of Paris Entrusts to the Air Her Call to France, reproduced as Figure 1.)3 A few weeks after Gambetta’s balloon voyage Wagner commented: “The French government in balloons would be a subject for an Aristophanic comedy; a government like that, up in the air in both senses, would provide a writer of comedy with some splendid ideas” (CWD, 6 November 1870).4

Figure 1. Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, The Balloon: The Besieged City of Paris Entrusts to the Air Her Call to France, 1870. Oil on canvas (Paris, Musée d’Orsay).

The remark suggests that Wagner had in mind Aristophanes’ political satire, Birds, in which two disgruntled Athenians, Euelpides and Peisetairos, join forces with assorted avians to establish a rebel utopia, “Cloudcuckooland” (Nephelokokkugia), suspended in the air between the domain of humans on earth and the gods above. And indeed, between the time of Gambetta’s balloon flight and this inspiration, a month later, for a modern satire in the “manner of the ancients,” Richard and Cosima had been reading Aristophanes’ Knights and Peace (though apparently not Birds, just now).5 The previous February they had read together Frogs, Wasps, and Acharnians.6 Early in 1874, following an evening of Buddhist studies, Richard began to read Lysistrata to his wife (“Great fun,” she remarks), but cut it short two days later: “There is too much licentiousness, in which women can take no part” (CWD, 26, 28 January 1874; not a surprising verdict, but more than a little ironic in view of the women’s role in Lysistrata!) Whatever elements of these comedies Wagner may have drawn on for his own modern political satire (details from Frogs and Peace also provide lively models), the aptness of the Aristophanic oeuvre as a whole to Wagner’s purposes is clear enough: the pervasive role of topical political references, pointed and often coarse cultural satire, and a background of military conflict in the protracted wars between Athens and Sparta. A trait preserved in Aristophanes from a more primitive, “non-literary” tradition of comedy, as Kenneth McLeish notes, can be seen in “numerous short interludes which lampoon known individuals, picking on eccentric character traits and demolishing by ridicule.”7 Later references in Cosima’s diaries to Aristophanes also suggest Wagner found particular inspiration in the poet’s uninhibited naming of his targets (his unceasing stream of invective against the demagogic Athenian leader Cleon, for example), in addition to his ludicrously fantastical-satirical scenarios.

During the October 1870 readings that led to the Kapitulation project, Wagner remarked “how naïve and full of genius” the Greek comic poet was—not so much as a poet, he adds, but as “a dramatist, and above all a musician” (CWD, 18 October 1870). Naturally, the master of the music drama was well attuned to the role of music in Greek comedy, no less than in tragedy. The role of the chorus, dance, and the variety of meter and verse (or whatever he gleaned from the translations he read, presumably those of Gustav Droysen) must have commanded his attention during his readings of Aristophanes, first in the 1840s and now during this wartime intermission to his completion of the Ring of the Nibelung cycle. His own political farce about the French war was thus also conceived as a musical comedy. And as Wagner reasonably deduced, the most suggestive modern analogue to the “musical” satire of Aristophanes was the opéra bouffe or “operetta” of Jacques Offenbach, that guiding spirit of Second Empire giddiness. Another German-Jewish expatriate in Paris, Max Nordau (later famous as the diagnostician of fin-de-siècle cultural “degeneration”) specifically dubbed Offenbach “the Parisian Aristophanes,” the title of an essay on the cultural phenomenon of Second Empire operetta written in the 1870s.8 This contemporary model is made explicit in the concluding episode of Eine Kapitulation, where Offenbach himself emerges from beneath the stage (the “Underworld,” as it were), playing one of his tunes on the cornet à pistons. While Victor Hugo, here transformed into the “Genius of France,” floats above the stage in Gambetta’s balloon, Offenbach leads the whole cast in a series of cotillion dances, concluding with a galop meant to evoke, no doubt, the “Galop infernal” of Orphée aux enfers—that is, the famous “cancan” that became the essential signature of Offenbach and the operetta, rather like the “Ride of the Valkyries” became that of Wagner and the music drama.

Offenbach’s operettas were widely perceived as the very embodiment of the Second Empire’s pleasures and vices—the frivolous irresponsibility and political cynicism that brought France low, as was often claimed at the time.9 The modern operetta would thus seem a natural vehicle for Wagner’s satirical celebration of the regime’s collapse (even if his central characters are drawn from the government of the nascent Third Republic). But the initial point of reference remains Aristophanes and the Greek theater, as the opening stage directions already make clear:

The proscenium, as far as the middle of the stage, represents the square before the [Paris] Hôtel de Ville and is used in the course of the piece in the manner of the “orchestra” of the ancients; in the center, in place of the Thymele10 is the altar of the Republic, adorned with Phrygian cap and fasces…. The classical stairs on each side of the stage lead to the raised portion in the rear, representing the balcony of the Hôtel de Ville; behind it the towers of Notre Dame and the Panthéon are visible.11

Wagner indicates that the “altar” should resemble a modern prompter’s box, and should also provide a practicable mode of entrance and exit. The pointed references to the disposition of the classical theater—“orchestra” or dancing platform for the chorus, the altar, the skene or stage building behind the orchestra, the lateral stairs or walkways (parodoi, referred to here as the antike Treppe)—are all offered as further proof of the author’s credentials for emulating the “manner of the ancients,” the antike Manier.12 (Perhaps, too, classical erudition is meant to justify a joke that even Wagner sensed was in questionable taste.)

The cast of this Aristophanic operetta includes contemporary personages (for example, the foreign minister and vice president of the new republic, Jules Favre, Léon Gambetta, Victor Hugo, the photographer Nadar, and Émile Perrin, director of the Opéra) as well as representative “comic” types (Alsatians and Lotharingians speaking in dialect). These figures are deployed in a whimsically parodic and improvisational scenario after the manner of Aristophanes, without any of the linear narrative or comic imbroglio typical of modern operetta. Still, the superimposition of some elements from Parisian operetta onto the classical template was easily effected: noisy marching songs, giddy dances, familiar tunes in the vaudeville tradition of popular allusion, and a steady stream of choral intrusions evoke the kinetic energy of modern operetta and of classical “Old Comedy” alike.

Wagner himself scarcely deserves credit for discovering the affinity of the modern opéra bouffe with Old Comedy, since two of Offenbach’s signal successes, Orphée aux enfers and La belle Hélène, treat the gods and heroes of Greek antiquity in a mockingly irreverent manner distinctly reminiscent of Aristophanes, updated to allude to the vie parisienne of the mid-nineteenth century. Max Nordau, as noted above, wrote appreciatively about Offenbach as “The Parisian Aristophanes.” In that essay, written apropos of an 1876 revival of La belle Hélène, Nordau also mounts an interesting argument that it is the “philosophical” contribution of Offenbach as a musician that earns him this title. Offenbach, he says, is altogether a perfect product of his times, a representative man (“as the English express it so nicely”).

The intellectual currents and perspectives of our times are alive in him, and he gives an entirely original expression to them. The secret of his success is that he thinks in a modern way, that his talent beats with the very pulse of our century. Here is the explanation for the fact that a poor German Jew could arrive in Paris, unknown and without recommendations, and yet, after a brief period of struggle for survival, could so soon establish himself among the first rank of international celebrities.13

No doubt Wagner was keenly aware of this. Like that other German Jew of his generation, Giacomo Meyerbeer, Offenbach had made a fabulous success precisely where Wagner had failed. Unlike Meyerbeer, he did so without the advantages of money, education, or connections. He flourished, as Nordau suggests, not simply because of his native musical talent, but because of an uncanny ability to take the cultural “pulse” of this modern metropolis. Other composers of the “light genre” boasted similar melodic gifts: Johann Strauss Jr., Franz von Suppé, Charles Lecocq. They befriended the popular muse quite as fully as did Offenbach, but for the most part their musical comedies have not attained the immortality of Offenbach’s, Nordau remarks. For they are, in the end,

nothing more than composers; Offenbach, on the other hand, is a composer and a philosopher. He is a true innovator; he has extended the realm of music, introducing polemics into the field of music. He is the creator of a satirical music. The melodies of other operetta composers are pleasantly harmless, while Offenbach’s are pointed, and have someone or something as their target. Offenbach is one of the chief challengers in a struggle against authority and tradition; he is the champion of those who would fight against received opinion. With a merciless hand he has torn away the halo from the head of Greek mythology, exposing its figures to the mockery of the world.14

Besides skewering the pious worshipers at the altar of “classical” learning (the culture of the Gymnasium and the University) through his parody of the cardboard heroes of classical mythology, Offenbach set his sights on the modern “idols” of royalty and the military in what Nordau calls his Tendenzoperetten (topical operettas) such as Barbe-bleu, La grand-duchesse de Gerolstein, La Perichole, or Madame l’archiduc. Obviously, the libretti of Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy are a crucial ingredient of Offenbach’s musical satires, but the texts alone would not qualify the operettas for the Aristophanic prize, as Nordau sees it. He reads this “philosophical” element in the cultural-critical character of Offenbach’s scores from the vantage point of post-Second Empire Paris. But it seems that the great musical “philosopher” of the century, Wagner, already appreciated something of this critical potency at the outbreak of the French-German war. He intimated, it seems, a distinctively urban and even political modernity in Offenbach that challenged the anti-modern mythologizing of his own music dramas and their effort to fight the commodification of culture (an urban and Jewish phenomenon, as Wagner saw it) with an aesthetic “truth” he wanted to regard as timeless and priceless.

Eine Kapitulation is among the least noticed of Wagner’s published works—deservedly so, perhaps. It can be seen as a companion piece of sorts to the (nowadays) much more frequently cited essay “Judaism in Music.” That formal denunciation of “public enemy no. 1,” the Jews, was published pseudonymously in 1850, at a time when Wagner was not yet much a name to conjure with, but later reissued under Wagner’s name in 1869, when he was very much one. Soon after, the war of 1870 prompted this less formal, more playful, but similarly vicious attack on “public enemy no. 2,” the French. Subsequent history has given much greater urgency to the issue of Wagner’s outspoken anti-Semitism, and his fulminations against the French have paled in significance. Today Wagner’s anti-French invective seems scarcely more relevant than his rantings against the Jesuits, or for that matter, the Prussian “Junkers.” Throughout the later nineteenth century, however, the anti-French rhetoric figured more prominently in Wagner’s controversial status than did his denunciation of the Jews. And in the last months of 1870 it was the besieged Parisians who were suffering under the scourge of German “barbarity,” as it was styled in the French press, as well as some foreign papers sympathetic to the French cause. Such sympathy had been scarce at the outbreak of the war in August, since the French were at least nominally the aggressors and Napoleon Ill’s political reputation was reaching a low ebb, both abroad and at home. But by November 1870 the Prussian siege had begun to reduce much of the Parisian population to near-starvation, while dwindling supplies of fuel began to reduce grand parks such as the Bois de Boulogne to mere deserts.

The attempt to carry on the gastronomic traditions of the French capital under siege conditions captured the collective imagination. “The emergence of horse, dog, cat, and rat as part of the Parisian diet became a staple of conversation,” as Rupert Christiansen notes, and menus featuring these new ingredients dressed up in elegant culinary preparations became emblematic of the privations suffered during the siege as well as during the political chaos of the Paris Commune the following spring. (Figure 2 reproduces a painting by Narcisse Chaillou commemorating this topical feature of Parisian life during the siege: a young butcher’s apprentice prepares to apply his skills to a freshly caught rat against a trompe-l’oeil background of posted bills advertising political plays and pamphlets, household necessaries, and, in front, an almanac for the new year with a feature on “cooking in the time of siege.”) Wagner was not alone in his fascination with the role of the rat on the Parisian menus, but his whimsical deployment of it in the scenario of Eine Kapitulation has seemed to most observers a lapse of taste and judgment not readily excused by either the conventions of Aristophanic comedy (whatever allowances it made for crude and earthy humor) or by the vehemence of the composer’s political and cultural opinions. (Perhaps, though, Wagner did exercise some element of self-restraint in refraining from giving his comedy the very plausibly Aristophanic title Rats.)

Aside from these cultural and ethical factors, the specifically “Aristophanic” manner of Eine Kapitulation also accounts for its obscurity. Scholars have worked hard over the centuries to illuminate the whole range of poetic idiom and cultural reference to mythical, literary, political, military, and civic personalities embedded in the plays of Aristophanes. The figures who populate Wagner’s comedy are scarcely remote, by comparison. They were the stuff of daily headlines in the international press some 140 years ago (indeed, Eine Kapitulation is a kind of “CNN operetta” of 1870, a political comedy skit with certain pretensions to learning in the tradition of university theatricals of earlier eras—similar to what Nordau called the Tendenzoperetten of Offenbach). Yet the daily news of a century ago is also a kind of ancient history, which may also have contributed to the general neglect of Wagner’s questionable “comedy” and its politics.

Figure 2. Narcisse Chaillou, Skinning a Rat for the Pot: A Rat-Seller in the Siege of Paris, 1870. Oil on canvas (Paris, Musée Carnavalet/Roger-Viollet).

One justification for my dragging this nearly (and perhaps best) forgotten “jest” briefly back into the light could be its value as evidence of Wagner’s creative reception of Aristophanes—a potentially interesting footnote, at least, to the more familiar pedigree of the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk in the tragic drama of the ancient Greeks. Eine Kapitulation is of potential historical interest, too, as a document of Wagner’s and Germany’s attitude toward the French at this critical juncture of modern European history. (The French-German conflict of 1870 might be regarded as something like the Rheingold to the Götterdämmerung of European warfare some seventy years later.) Just as Bismarck felt he needed a war against France to consolidate support for the unification of the German states under a Prussian leadership, Wagner perhaps considered a war on French culture (or rather, civilisation) valuable in cultivating the ground for a musical-dramatic festival that would serve as a unifying “cult” of true German art; within half a year he and Cosima were investigating Bayreuth as a venue for the great national rite that would be consummated by the premiere of the Ring cycle. (Coincidentally, Wagner was received by Bismarck in Berlin later on the same trip in the spring of 1871; but the hope that Bismarck and the Kaiser would patronize Wagner’s grand enterprise in the name of the new Reich would be repeatedly disappointed.) Finally, this wartime pièce de circonstance is a unique document of Wagner’s in some ways surprising response to Jacques Offenbach, a German Jew who—like Meyerbeer or Heine—forsook the Vaterland to become the toast of Paris, and whose steady stream of operettas from the 1850s and ‘60s suggest a swarm of satyr-plays to the “trilogy” of Meyerbeer’s grand operas (Robert le diable, Les Huguenots, Le prophète) that continued to dominate the international repertoire through those decades. Where Meyerbeer was to Wagner an antagonizing rival and even an operatic father figure of sorts who had to be slain twice over (as a “father” and as a Jew), Offenbach operated in a sphere wholly unconnected to him. Eine Kapitulation makes fun of Offenbach as the “bandmaster” of a decadent, culturally bankrupt regime. But in an odd way it also represents a latent desire to compete with Offenbach: at the very moment he is styling himself the high priest of German culture, Wagner succumbs here to a passing temptation to address the modern, urban Volk with a political-satirical operetta: “classical” in form but in the absolutely “modern” style of the Variétés, the Gaîté, and the Bouffes-Parisiens. (As we will see, Wagner was for a time quite earnest about getting his comedy composed and staged, if not necessarily by himself or under his own supervision.) Rather than slaying Offenbach, Wagner imagined becoming him, if only for a day, and in semi-respectable classical disguise.

Couching his anti-French “operetta” in the guise of an early classical comedy not only provided an aura of intellectual, scholarly (German) respectability to the enterprise; it also excused, in a way, the unsavory, distinctly unrespectable character of the humor. The so-called Old Comedy of Aristophanes enjoyed a kind of carnivalesque dispensation to ridicule contemporary personalities with relative impunity, and even to indulge in scurrilous, obscene jesting that would never be tolerated as part of normal public discourse. The obscenity and satirical unrestraint of Old Comedy are comprehended under the term aischrologia, or “speaking what is shameful,” as Stephen Halliwell remarks. The genre “incorporated an extreme but temporary escape from the norms of shame and inhibition which were otherwise a vital force” in Athenian society.15 Something of this carnivalesque dispensation applied also to the works of Offenbach and his long-term collaborators Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy. With a candor transgressing the bounds of what would be acceptable in the “legitimate” theater or in a newspaper editorial, these musical revues and farces skewered the pretenses of Second Empire Parisian society (or for that matter the foibles of German Kleinstaaterei and Prussian militarism, in a work like the Grand Duchess of Gerolstein). For Wagner, Offenbach’s infectious frivolity presented at once the perfect target and the perfect vehicle for his own scurrilous satire on the French enemy. In parodying the “Mozart of the Champs-Elysées,” Wagner supposed he could have his fashionable Parisian gâteau and eat it, too. Indeed, in emulating the giddy frivolity and nonsense of the modern operetta in his neoclassical musical farce, Wagner was not so much attacking Offenbach as “consuming” him, cannibalizing an alien musical-theatrical genre in a gesture of covert cultural imperialism.16 Just as the end of the Franco-Prussian War would see the crown of empire and military dominance usurped from France by the new German nation (declared at Versailles in January 1871), Wagner briefly imagined conquering the Parisian operetta and transplanting it to the popular stages of the new Reich for the purposes of satirizing the defeated Empire.

True to its Aristophanic models, Wagner’s satirical skit is built around a loose tissue of topical allusion and whimsical (even crude) imaginative conceit, difficult to reduce to a cogent narrative core. Roughly summarized, it goes something like this. Victor Hugo returns from his nineteen-year exile to a newly republican Paris, under siege by the Prussian army.17 (Hugo sneaks in through the sewers, famously explored in the climactic sequence of Les misérables.) He observes the dilemmas and divisions of the provisional (National Defense) government, and is at the same time courted by a nebulous, underground socialist faction, headed by Gustave Flourens. A debate over whether the new state should banish religion in favor of an official atheistic policy is resolved through the decision of opera director Émile Perrin to promote opera and ballet to the status of official national “cult.” French opera, and above all ballet, Perrin argues, will serve to rally the support of all Europe—even the Germans cannot resist. The photographer Nadar makes a startling and uncanny appearance; his photographer’s hood is inflated to serve as a balloon. The republican leader Léon Gambetta volunteers to join Nadar in an aeronautical expedition to collect the dispersed personnel of the opera and ballet from the provinces and the eastern front. While these two hover in their hot air balloon above the stage, the underground socialist faction (identified as “the Blacks” rather than the Reds) tries to seize control of the government, led by the communard Flourens.18 A chorus of human-sized rats emerges from below, which Flourens and his followers try in vain to catch and slaughter. Gambetta returns, full of promises but empty-handed. He commands the people not to slaughter the rats for food, however, as they hold the secret to the ultimate victory of France and the new regime. Jacques Offenbach appears (also from below stage), playing a cornet à pistons and conducting the chorus and assembled cast in a series of cotillion dances. Under the influence of his music, the rats are transformed into a female corps de ballet “in the lightest of opera costumes.” Victor Hugo returns ex machina as “the Genius of France,” in the balloon vacated by Gambetta. While Hugo delivers a valedictory recitative and aria, the rest (including an international delegation of diplomats) dance a vigorous and awkward cancan. Hugo is “transfigured by the light of a Bengal fire.”

Wagner’s knowledge of Aristophanes and the Greek Old Comedy seems to have been limited to his own occasional readings. He first encountered the poet in the course of his intensive study of the classics during his later years in Dresden. In the summer of 1847, as he recalls in Mein Leben, he would slip off to a secluded, shady corner of the gardens behind the Marcolini Palais, “where I would read, to my boundless delight, the plays of Aristophanes … having been introduced by The Birds to the world of this ribald darling of the Graces, as he boldly called himself.”19 Otherwise, we only know about his (sometimes expurgated) readings for Cosima in 1870 and occasionally again in later years.20 It is not surprising that his informal attempt at a “comedy in the manner of the ancients” reflects the structure and detail of Aristophanic comedy only loosely, at best. All the same, it is perfectly possible to identify the model.

The expository prologos in Old Comedy may take various forms. Among the earlier plays of Aristophanes a solo character is sometimes found reflecting on a scene just “uncovered” by the break of day: Dicaeopolis brooding before the still-closed gates of the Athenian assembly in Acharnians, or Strepsiades in Clouds waking up just before dawn to survey the signs of extravagance and waste in his household, prompting him to learn the art of sophistry from his neighbor Socrates so he might argue his way out of his debts. The playwright is also fond of injecting a bit of earthy, scatological humor near the beginning of the prologos: the care and maintenance of Trygaios’s giant dung-beetle in Peace, for example. Wagner combines both elements at the beginning of Eine Kapitulation, when Victor Hugo emerges from the depths of the Parisian sewers through the altar-cum-prompter’s box to find himself at the place de Grève, the site of the city hall. In an extended opening monologue he reflects on the adventurous route of his return, and how it may furnish him—celebrated for his prolific output in poetry as well as prose—with the stuff for untold volumes yet to come. (The extensive bawdy humor in the Greek comedies finds no place here, however, beyond the “lightly clad ballerinas” into which the chorus of rats is transformed.)

It is not clear if Wagner understood the convention of the parodos—the official introduction of the Chorus, following the prologos or exposition of the principal characters and their concerns—in which the Chorus generally engages with the cause of the comic protagonist, either pro or contra. Aware perhaps of the way the Chorus in Aristophanes might change voice or identity (especially later, in the parabasis), Wagner deploys his Chorus in multiple roles, even somewhat indiscriminately.21 Right after Hugo’s opening monologue we hear indeterminate “voices” from below. Soon after that, a “Chorus of the National Guard” marches on singing (and subsequently high-kicking), well before it is entrusted with any form of more substantial dramatic address.

Though structurally premature, according to the pattern of Old Comedy, this Chorus of the National Guard embodies an attempt to wed the manner of Aristophanes to that of Offenbach. In anatomizing the word Republik the Chorus generates a kind of musico-poetic nonsense reminiscent at once of the croaking in Aristophanes’ Frogs (“Breke-ke-kex koax koax”) as well as the playful rhythmic deconstruction of text that was a specialty of Offenbach. Compare the text of Wagner’s republican Chorus, for instance, with a well-known example of Offenbach’s musical wordplay in the “Marche et couplets des rois” from Act 1 of La belle Hélène:

| CHORUS OF NATIONAL GUARD: | MÉNÉLAS: |

Republik! Republik! Republik blik blik! Repubel Repubel Repubel blik blik! (usw.) Repubel pubel … pupubel … Replik! (usw.) (Eine Kapitulation, GSD, 9:7) |

Je suis l’epoux de la reine (La belle Hélène, Act 1) |

Following the Offenbachian model, Wagner has tried—somewhat laboriously—to tease out punning syllables from this syllabic deconstruction of the word Republik: “blik” to suggest Blick! (Look!); “pubel” to suggest, perhaps, the French poubelle (trash can). He tries this and similar effects elsewhere: isolating the last syllable of Gouvernement—“ment, ment!”—to suggest a conjugation of the verb mentir (to lie); punning between German and French (the Chorus hails the aerial departure of Gambetta and Nadar: “Fahr wohl, und vole au vent! Gouvernement! Gouvernement! Vol-au-vent! Vol-au-vent!”); or simply inventing “froggy” sounds (or is it the crowing of the Gallic cock?) to celebrate the arrival of Offenbach as national bandmaster: “Krak! Krak! Krakerakrak! / Das ist ja der Jack von Offenback!”22

The closest Wagner comes to providing a proper parodos, the formal introduction of the Chorus, occurs with the presentation of the republican government, seated on the balcony of the Hôtel de Ville, which occupies the position of the classical skene. In response to Victor Hugo’s inquiries about the state of the city hall and government, the Chorus calls forth the members of the new regime, to vigorous “military” rhythms and gestures:

Regierung, Regierung! Wo steckst du? Die Feinde dahin, wann streckst du? Wo träumen die Jules? Was treibt der Gambetta? Mach’ ich ihm Beine Zur kriegerischen Stretta? (Eine Kapitulation, GSD, 9:13) |

O Government, where are you hiding? Our foes now, why aren’t you fighting? Where dream all those Juleses? What’s up with Gambetta? Let’s get his feet moving to a military stretta. |

Another formal articulation of this juncture is the sudden disappearance of Hugo from the scene, a Looney Tunes variation on the end of Don Juan: “The Chorus grabs Hugo by the head, while his feet are being pulled from below; his figure becomes elastically elongated”; voices from below summon him again, as his head snaps back to join the rest of him below stage. Though brief, the choral sequence here fulfills the common function of the parodos by underlining the fundamental situation of the comedy (here, the instability of the new government) in verse, music, and dance, while also setting up the confrontation or debate at its center.23

This central debate, or agon, duly follows: the discussion between the “three Juleses” regarding an official religious (or anti-religious) policy for the new regime. (Later, there is a larger confrontation between the underground socialists and the moderate republicans aboveground.) The decision in favor of reestablishing opera—or more particularly, ballet—as a national “religion” with international and commercial appeal resolves the agon and at the same time establishes a further central characteristic of the Old Comedy, a fantastical quest or some other quixotic scheme, loosely directing the remainder of the plot. In Frogs, Dionysus journeys to Hades to bring back the “good old boys” of Tragedy, Aeschylus and Euripides; in Birds, the two Athenian men join forces with another species to establish a new utopian republic of the air; in Lysistrata, the women occupy the Acropolis in their antiwar protest and temporarily seize sexual as well as political control from the Athenian men; in Peace, Trygaios flies to Mount Olympus and back on a beetle, likewise with the aim of ending the protracted war with Sparta. In Eine Kapitulation, Wagner reimagines Gambetta’s escape to Tours by hot-air balloon as a recruiting expedition for the Parisian opera and ballet. Like Trygaios’s beetle-borne flight to Olympus, Gambetta’s balloon journey is intended as a means of concluding hostilities, in this case by garnering international support for the Opéra and its indispensable corps de ballet. (Unlike Aristophanes, whose comedies repeatedly protest ill-conceived Athenian military campaigns, Wagner himself remained hawkish to the end, waxing indignant at the Prussians’ hesitation to conclude the siege of Paris with a large-scale bombardment.)

Perhaps the most distinctive formal sequence of Old Comedy is the parabasis, in which the Chorus addresses the audience at some length on the subject of the play or otherwise editorializes—typically exhorting the judges to award the playwright first prize in the competition (the “Lenaea” or the “City Dionysia”). At first glance a parabasis seems to be entirely lacking in Eine Kapitulation. Wagner was of course always willing to blow his own horn; but then, he was not actually competing with anyone (except perhaps Offenbach, in an imaginary way). On closer consideration, however, he has preserved something of the parabasis function, if we view it as being transferred from the Chorus to the role of Gambetta in his balloon. The term parabasis indicates, literally, a “stepping aside” on the part of the Chorus from its dramatic role to assume the poet’s voice or some neutral voice, rather like the Chorus of Greek tragedy. Here, it is Gambetta’s balloon, the central prop of the piece, that almost literally breaks through the theatrical “fourth wall”: Wagner instructs that it should float out beyond the Chorus (and “Orchestra” stage space) “as far as possible into the audience” (GSD, 9:26). With the aid of Nadar’s opera glasses, Gambetta surveys the audience and announces that throughout Europe, Germany very much included, everyone is eager to return to the theaters of Paris. Wagner explicitly addresses his imagined German audience through Gambetta here: the main point of his satire, he insisted, was to castigate his own countrymen for surrendering so readily to the lure of Paris fashions, above all Parisian music and theater. (As Gambetta surveys the continental landscape from on high and catalogues the peoples longing to return to their accustomed Parisian diversions, the Chorus asks, “And what about the Germans?” “They sit there peaceably among the rest,” replies Gambetta; “they have capitulated, and are blissful at the prospect of returning to our theaters!”)24 Perpetuating this bit of (characteristically Aristophanic) meta-theatrical comedy, Gambetta and Nadar steer their airship into the wings in search of artistes as well as costumes to refurbish the Paris stage.25

From the perspective of later Latin and modern European comedy, with its traditional emphasis on the construction and resolution of intrigue, the conclusion (or exodos) of the Old Comedy can seem a bit slapdash. Wagner’s Kapitulation follows suit. Both of them naturally turn to theater’s originary ingredients, song and dance, to effect comic closure. As the Parisians are about to attack and consume the rats that have swarmed up from the prompter’s box, Gambetta halts them, anticipating their transformation into the redemptive corps de ballet. “Just as the tumult reaches its frenzied peak, the sound of a cornet playing an Offenbach melody is heard from the prompter’s box” and the composer’s torso emerges, Erda-like, from the subterranean depths to celebrate the mock victory of Parisian light entertainment. The concluding galop général led by Offenbach suggests the cordax of Old Comedy, a riotous comic dance sometimes concluding the play, “associated with lewdness and drunkenness.” This piece of high-spirited entertainment would round out the performance, willy-nilly, with the rhetoric of sheer physical exuberance, something like the “jig” that traditionally ushered out any performance, either comic or serious, in the Elizabethan theater. Aristophanes had actually claimed to purge comedy of this particular pandering to common tastes; but at the end of Wasps he recalls it parodistically, bringing on the “three sons of Carcinus” (a rival comic playwright), to execute a coarse, athletic high-kicking dance, itself suggesting a sort of classical cancan.

Although the apotheosized Victor Hugo occupies the flying machine in the closing scene (as the “Genius of France”), it is really Offenbach who figures as the piece’s parodic deus ex machina when he pops up from the same altar-cum-prompter’s box whence Hugo had emerged at the beginning, ready to save the day with his music. Jules Ferry hails him as France’s “secret weapon.” Offenbach’s cornet has been mistaken by Flourens and his insurrectionary followers for the advancing Prussian army, and they accuse the Republicans of having capitulated to the enemy. But Ferry corrects them:

FERRY:

False claim! No capitulation! We bring you the most international individual of the world, who will secure for us the intervention of all European powers. The city that has this man within its walls is forever invincible, and has the whole world as its friend! Do you recognize this man of wonders, Orpheus from the Underworld, the venerable rat-catcher of Hamelin?26

Through the figures of Hugo and Offenbach, Wagner weds the idioms of mock exalted hymn and frenzied Dionysian dance to conclude his comedy in appropriately “classical” fashion. Both Hugo and Offenbach exalt the Parisian pleasures that Wagner means to denounce as exemplifying the moral and aesthetic decadence of modern France, admonishing the Germans to desist from their mad infatuation with such frivolities. The Germans, Wagner implies, must resist the blandishments that Hugo offers them in the form of an enemy ruse:

| HUGO: | |

Als Feinde nicht nehmt ihr Paris, |

As foes you’ll never take Paris, |

Hugo goes on to point out how Parisian opera has made German culture palatable to the rest of the world, citing the examples of Guillame Tell, Don Carlos, Faust, and Mignon. “So kommt und laßt euch frisieren, parfümieren, zivilisieren!” he exhorts in aptly Frenchified German (Come have yourselves coiffed, perfumed, and civilized!).28 The message, Wagner assumed, was perfectly clear. Celebrate with me the Untergang of Paris and all it represents, but for heaven’s sake don’t then continue to ape Parisian fashions, importing Parisian entertainments back into Germany and further risking the decline of our own culture.

If Eine Kapitulation approximates the model of Aristophanic comedy rather loosely, it is even further from providing a practical libretto in terms of the contemporary operetta, a “book” with “lyrics” viable for composition and staging. Apart from Wagner’s obvious lack of experience in either genre (ancient comedy or modern operetta), and quite apart from the fundamentally questionable nature of the material, the practical problem is precisely the admixture of these two very different models. For a viable operetta there are too few proper song or ensemble texts; notably missing are any of the couplets that were the essence of opéra bouffe. The Chorus, on the other hand, is deployed with indiscriminate frequency, presumably under the influence of Greek comedy; its many brief interjections would defy any normative compositional practice of Wagner’s day, whether in opera, operetta, or even his own “music drama.” Otherwise, the more concrete musical points of reference in the text derive, as we could expect, from the operetta: strongly rhythmic rhyming lines, abundant cues for marching and dancing, as well as generally frenetic stage business and a large dose of fantastic spectacle in the manner of popular pantomimes and melodramas (though not without some resonance with the fantastical scenarios and occasional stage effects that made the comedies of Aristophanes popular with his audiences).

Despite the implausible nature of the text as an actual libretto, however, Wagner at first fully intended to have his comedy set to music and performed at the same German theaters that were currently featuring the newly popular Parisian and Viennese operetta.29 If he had no particular compunction about associating his name with the text, he nonetheless would not compromise himself to the extent of composing music in the requisite style.30 That task fell to Hans Richter, future conductor of the first Bayreuth festival and then living with the Wagners at Tribschen as a combination house musician and au pair. (His fondness for joking and playing with the children, in addition to his versatile musical talents, suggested him as a good candidate for the job.) But the project withered quickly on the vine. A week after Wagner finished the text, Richter began composing (November 21, 1870). A week after that, Wagner sent off a copy of the text to Franz Betz (the first Hans Sachs and Wotan, then resident in Berlin) suggesting he peddle it to the “minor” metropolitan theaters—most likely he had in mind the Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater, which had come to specialize in productions of Offenbach’s operettas, along with the “Krollsches Etablissement” and the Viktoria Theater. On December 16, Richter previewed his music to the Tribschen household. He “admits to us,” Cosima noted that evening, “that he would find it embarrassing to put his name to it.” The following day “Betz returns Die Kapitulation; the theaters are frightened of the production costs” (apparently Betz’s face-saving excuse).31 “R. is basically glad, for the situation in Paris has changed, the mood is no longer the same.” For weeks the besieged Parisians had been freezing and starving, reduced to eating not only most of the city’s horses but even their own pets, in addition to the much reported rats. Even Wagner had to admit that his little satire might not be appreciated quite as he had hoped.

What had he hoped, then? Eine Kapitulation began as a private diversion, not unlike the Siegfried Idyll he was simultaneously composing in secret to celebrate Cosima’s birthday that Christmas. But Wagner was always able to convince himself that his views on any subject were of ultimate value to society. When he eventually published the text in the ninth volume of his collected works (first edition, 1873), he prefaced it with a somewhat shamefaced apologia.32 The French themselves had been “performing” their envisioned defeat of Germany for public entertainment before the outbreak of the war, he claimed.33 The Germans, for their part, had been satirizing the subsequent French military defeats in popular theater and cabaret. Here, he explains, he saw an opportunity of reforming the taste of “our so-called Volkstheater, which has heretofore been limited to poor imitations of Parisian entertainments.”34 Wagner recalls, too, in this preface the relief of a “young friend” (i.e., Hans Richter) when his anonymously submitted text had been rejected for production, “since he confessed he would have found it impossible to put together the necessary music à la Offenbach; from which we both concluded that all things require a certain genius of one kind or another, and this was one kind we readily conceded to Herr Offenbach himself.” In this minimally self-effacing way Wagner concedes a small “capitulation” on his own part, before going on to underline his alleged principal aim: to castigate his countrymen in their excessive cultivation of French fashions and music.

Wagner’s brief (editorial) “capitulation” in this foreword to the published text suggests a grudging admiration for the “peculiar genius” of Offenbach. And whether his satire was principally aimed at the decadent frivolity of the French or at the Germans who imitated them, music à la Offenbach was deemed the appropriate vehicle for this “Lustspiel in antiker Manier” that attempted to revive the comic art of Aristophanes, genuinely admired by Wagner, in a modern style and context. There is a further confluence of his views on the Greek comedian and the German-Jewish-Parisian musician. Both at the time of his first reading of Aristophanes in the late 1840s and again at the time of the Franco-Prussian war, Wagner hailed the Old Comedy as a laughingly critical, self-aware embrace of Athenian “decline” toward the end of the fifth century BCE. It seems that he perceived something similar in the operettas of Offenbach: a popular art merrily conniving at the perceived decline of French political and cultural hegemony in Europe. Under these circumstances, operetta would be one product of modern Parisian culture Wagner was willing to embrace.

It is difficult to say how much of Offenbach’s music Wagner had actually heard. Obviously, it does not figure prominently in the repertoire of Bayreuth Hausmusik. (Richter’s halfhearted tryout for Eine Kapitulation was probably the closest approach to it there.) It would not be unreasonable to speculate on a sort of prurient curiosity on Wagner’s part toward Parisian operetta, but it would have to remain speculation. To judge from Wagner’s few recorded remarks about Offenbach, and from the composer’s cameo role in Eine Kapitulation, Wagner seems to have regarded him principally as a composer of dance music—instinctively responding, perhaps, to that compulsive sense of rhythm and “the body” in Offenbach’s idiom that, as Nietzsche was to complain, became increasingly absent from Wagner’s own music.35 And of course, then as now, Offenbach was associated in the popular imagination with the cancan, a dance of somewhat obscure origins that acquired iconic status as the music of uninhibited Parisian debauchery once it became identified with the riotous “Galop infernal” of Orphée aux enfers. Even if Wagner never intended to put himself forward publicly as a composer of operetta, we would be justified in speculating on the intriguing question of what sort of music Wagner “heard” in writing the text of Eine Kapitulation, especially in view of the authentic Wagnerian dogma that the composer generally anticipated important details of musical composition in drafting and versifying the texts of his operas.

To judge from the “lyrics” of Eine Kapitulation, as distinct from the prose dialogue, Wagner seems to have been particularly attracted to the rhythmic-musical wordplay of his model, as suggested earlier. Offenbach’s librettists, Meilhac and Halévy, were ingenious in devising material for such effects. A classic example is the opening chorus of La vie parisienne (1864), one of the most frequently performed of their works by 1870, in which the chorus of railway employees simply rattles off, to the inexorable rhythm of a modern locomotive, the names of all the stops on the “Western line” between Paris, St.-Mâlo, and Brest. An extreme case is the “Alphabet Sextet” from the postwar operetta Madame l’archiduc (1874), where two comic servants mistake the conspiratorial code “S-A-D-E” (“Supprimer Archi- Due Ernest” or “Down with Archduke Ernest”) for an alphabet song they recall imperfectly from their school days, such that the characters end up spewing out a chaotic string of letters resembling modern-day computer programming. Elsewhere, as paradigmatically in the “Marche et couplets des rois” introducing the Greek kings in Act 1 of La belle Hélène, it is Offenbach’s musical setting that teases out latent rhythmic and verbal jests, puns, or simply amusing nonsense. Agamemnon, for example, announces himself, “Le roi barbu qui s’avance, c’est Agamemnon,” and then renders his royal beard (“Le roi barbu”) a silly, meaningless expletive by isolating the syllable -bu (“-bu qui s’avance, -bu qui s’avance”), echoing the comical march rhythms of the kings who have preceded him. Or, to cite one last example, in the “Rondeau des maris récalcitrants” that concludes Act 2 of La Périchole, Don Andrès leads the chorus in anatomizing the syllables “ré-cal-ci-trants” as he admonishes the uncooperative husband of La Périchole, Piquillo, whom he has cruelly duped. Each syllable of the offending word (recalcitrant) is accompanied by a vigorous musical kick:

Conduisez-le, bons courtisans, |

Lead him, my good courtiers, |

Wagner attempts something of this sort a number of times with his “Greek” chorus. In the following, for example, he tries to pun the name of the director of the Opéra, Perrin, with the perron or balcony of the Hôtel de Ville (represented by the upper portion of the skene), incorporating a gratuitous, though rhythmical, reference to the troublesome cousin of Napoleon III, Prince Joseph-Charles-Paul (Napoléon-Jérôme), whose nickname “Plon-Plon” is matched up to the repeated final syllable of the doggerel-verse refrain word, Mirliton:

Seht, Bürger, Perrin Plon-plon-plon! |

Behold there, Perrin Plon-plon-plon!36 |

Toward the climax of his musical skit, Wagner has the “subterranean chorus” of underground socialist agitators marching to the old revolutionary anthem “Ça ira.” In this rendition, the demotic chanting and drumming shakes off the final syllable of “aristocrats” and transforms it into a new battle cry of “Rats, Rats!” (equating the two “underground” populations of wartime Paris while also capitalizing on the opportunity to invoke once again this signature feature of Paris under siege):

Pumperumpum! Pumpum! Ratterah! Ça ira, Ça ira, Ça ira! Aristocrats!—Crats! Crats! Courage! En avant! Rats! Rats! Ihr Ratten! Ihr Ratten! Pumpum ratterah! |

Pumperumpum! Pumpum! Ratterah! Ça ira, Ça ira, Ça ira! Aristocrats!—Crats! Crats! Courage! En avant! Rats! Rats! On rats! On rats! Pumpum ratterah!37 |

Surely Wagner was tapping out reminiscences of Offenbach in the back of his mind as he wrote this.

On the other hand, as mentioned before, his text pays scarcely any attention to the most basic unit of the operetta: the couplet. The sole example of the latter is embedded in Victor Hugo’s valedictory scena, the first strophe beginning “Die Barbaren zogen über den Rhein — / Mirliton! Mirliton! Tontaine!” followed by the appropriate choral refrain (“Dansons! Chantons!) and a second strophe (“Nun zogen wir selber über den Rhein — / Mirliton! Mirliton! Tontaine!”).38 Hugo prefaces his couplets with a parodic allusion to the apotheosis of Goethe’s Faust, by which Wagner mocks the French poet’s literary ambitions in contrast to the imputed triviality of the culture he celebrates.

HUGO: |

|

(rezitativisch, zu einer goldenen |

(in the manner of recitative, to a golden |

(Melodisch) |

(Melodically) |

| OFFENBACH: | |

| (kommandierend) | (calling the dance): |

| Chaîne des Dames! | Chaîne des Dames! |

CHORUS: Dansons! Chantons! (etc.) |

HUGO [Couplets, first strophe]: |

||

Die Barbaren zogen über den Rhein Mirliton! Mirliton! Tontaine!— Wir steckten sie alle nach Metz hinein— so gesteckt vom Marschall Bazaine! Mirliton! Plon! plon! In der Schlacht bei Sedon da schlug sie der grimmige MacMahon! Doch die ganze Armee General Troché— Troché—Trochu, Laladrons, Ledru— der steckte sie ein in die Forts von Paris. Im Jahre mille-huit-cent-soixante-dix da ist geschehen all dies!— Als echtes Génie de la France (usw.) |

The Barbarians have crossed over the Rhine Mirliton! Mirliton! Tontaine!— We captured them all there at Metz, just fine, with the help of our Marshal Bazaine. Mirliton! Plon! plon! As we fought at Sedon [Sedan] they were beat by the terrible MacMahon!39 The entire armée under General Troché—40 Troché—Trochu, Laladrons, Ledru— he hid them all safe in the forts of Paris. In the year mille-huit-cent-soixante- dix so it was, if you please!— As the genuine “Genius of France” (etc.) |

| OFFENBACH: | |

| Chassé croissé! | Chassé croissé! |

| CHORUS: | |

| Dansons! Chantons! (usw.) | Dansons! Chantons! (etc.) |

HUGO [Couplets, second strophe]: |

|

Nun zogen wir selber über den Rhein— Mirliton! Mirliton! Tontaine!— Wir nahmen das ganze Deutschland ein, à la tête Mahon und Bazaine—

Schnettertin tin! tin! Mayence und Berlin von Donau und Spree bis zum Rhin. General Monsieur auf Wilhelmshöh’— Tropfrau! Tropmann Tratratan! Tantan! Über die dreimalhundert-tausend Mann! Im Jahre mille-huit-cent-soixante-dix (usw.) |

Now we ourselves had crossed the Rhine— Mirliton! Mirliton! Tontaine!— We pushed back and back the German line, at the fore [Mac]Mahon and Bazaine. Schnettertin tin! tin! Mayence41and Berlin from the Danube and Spree to the Rhin. General Monsieur up at Wilhelmshöh’—42 Tropfrau, Tropmann Tratratan! Tantan Three times a hundred thousand men! |

OFFENBACH: En avant deux! |

En avant deux! |

Even the couplets shown here are preoccupied mainly with rhythmic-syllabic nonsense: folklike refrains such as “Mirliton! Tontaine!” and more attempted wordplay, or rather name-play, alluding, for example (and with no particular rhyme or reason), to the military governor of Paris, General Louis-Jules Trochu, or to the notorious serial murderer Jean-Baptiste Troppmann, “whose bestial crime,” Siegfried Krakauer notes, “was regarded by the revolutionaries as a symptom of the moral degeneration caused by the Empire.”43 The whole passage, incidentally, is accompanied by “Offenbach” playing his cornet à pistons. The verbal-rhythmic frivolity or nonsense is meant to underscore here the literal “non-sense” of the rest of the text in these strophes, which fantasizes French victory precisely at the key sites of signal French defeats of the past months (Sedan and Metz).

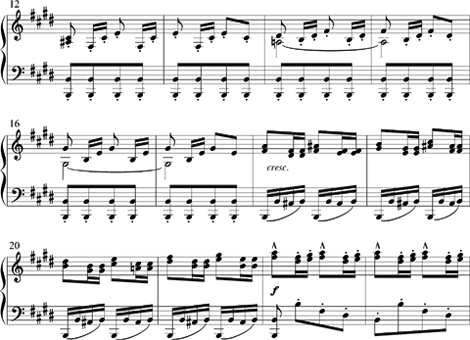

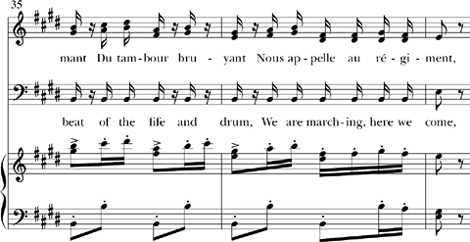

In nearly all of these examples Wagner seems to be invoking a genre of rhythmic march-song he would have known well from pre-Offenbach opéras comiques by Auber or Donizetti, among others: the rataplan. The prototype is to be found in the duet in Donizetti’s La fille du régiment, “Au bruit de la guerre j’ai reçu le jour,” whose rataplan refrain expressly imitates the sound of drums to which “militaire Marie” grew up as the regimental mascot (see Example 1). The repetitions and fragmentations of the word Republik in the Chorus of the National Guard at the opening of Eine Kapitulation (“Republik! Republik! Republik blik blik!”) are undoubtedly meant to echo this modern comic opera staple. (In fact, the closest Wagner got to composing any of this text is the notation of a repeated rhythm of two eighth notes plus a quarter note—followed by isolated eighth notes, presumably followed by rests, for “blik blik!”—which he entered above these lines in a prose draft for his Kapitulation project from mid-November 1870: precisely the traditional rataplan rhythm.)44

Example 1. Gaetano Donizetti, La fille du régiment, Act 1, “Rataplan” chorus, mm. 12-37.

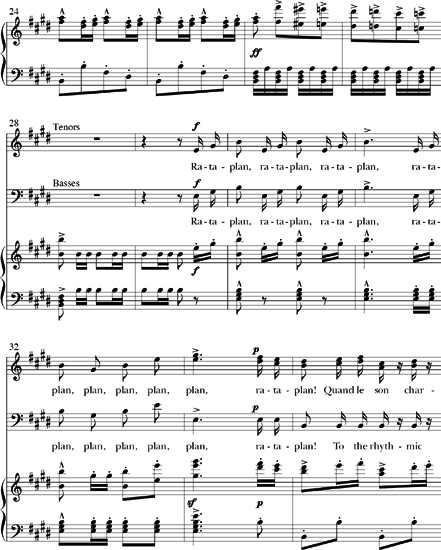

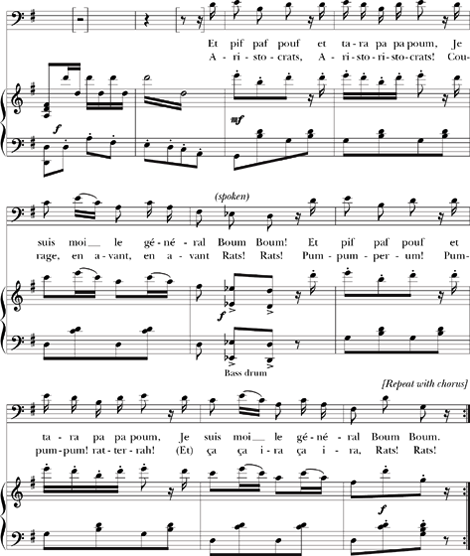

Closer in the background of Wagner’s wartime satire is Offenbach’s Grande-duchesse de Gerolstein. Premiered during the 1867 Paris World’s Fair, the piece turned into something of a topical Zeitoperette with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War three years later. The none-too-delicate Grand Duchess with her pronounced fetish for the military (“Ah que j’aime les militaires!”) seems to embody the very spirit of Prussia as it appeared to the outside world in these years, while the inept bumbling of her officers (no less than her own shameless favoritism for the handsome foot soldier Fritz) might have suggested all too neatly the conditions that led to rapid defeat of the French armies in August of 1870. At least for its first act, the Grande-duchesse is a veritable medley of rataplan-style songs and choruses. It is tempting to fit some of Wagner’s texts to Offenbach’s tunes—indeed, Hans Richter might easily have spared himself some effort by resorting to this military operetta by the maître himself. The mock-military couplets of Général Boum from the opening scene, “A cheval sur la discipline,” sport a refrain almost tailor-made for Wagner’s chorus of insurrectionary rats: “Et pif, paf, pouf, et tara papa poum!” (Example 2 suggests a simple contrafactum or re-texting to this effect.) The assorted French refrain words sprinkled throughout Victor Hugo’s own mock-military couplets at the end of Eine Kapitulation (“Mirliton! Tontaine!” or “Mirliton! Plon! Plon!”) inhabit more or less the same musical position and idiom as, say, the “ta ta, ta ta, rantaplan rantaplan” choral interjections to the Grand Duchess’s “Chanson militaire” (Act 1, no. 4).45 And even a presumably more lyrical number, such as the culminating “aria” in which Hugo delivers the moral (?) of the piece, fits without much strain to the concluding sections of the duet (Act 1, no. 2) introducing the ingénu protagonists of Offenbach’s operetta (with Hugo’s “als Feinde nicht nehmt ihr Paris” replacing Wanda’s line “Et si pour toi perdant la tête,” and so on to the end of the number).

Wagner himself, as we have seen, thought better of trying to compose in imitation of Offenbach. But one prominent critic, Eduard Hanslick, suggested he might have learned something from the exercise—for example, from Offenbach’s canny sense of rhythm. (Nietzsche, although entirely under the spell of Tristan und Isolde at this particular moment, would later come to agree wholeheartedly.) “I’m sure if you gave ten German composers the line ‘Ah que j’aime les militaires!’ to set,” Hanslick speculated, “at least nine of them would scan it uniformly in four trochaic feet; while scarcely one would come up with such a lively, piquant rhythmic setting as Offenbach did.” With regard to his other great strength, his innate musical sense of theatrical effect, Offenbach can only be compared with Wagner. “Indeed,” Hanslick continues, “when I consider how Wagner so often forgot all sense of proportion in his later works, I have to concede the more acute sense of theater to Offenbach.”46

Example 2. Offenbach, La grande-duchesse de Gerolstein, Act 1, Introduction: Couplets of General Boum (“Et pif paf pouf “), refrain with contrafactum from Wagner, Eine Kapitulation.

The hypothetical success or failure, in stylistic terms, of Wagner’s attempts either to revive the comedy of Aristophanes or to emulate the opéra bouffe of Offenbach might seem supremely beside the point, if that point is the one usually made about Eine Kapitulation, which is that it exemplifies all the worst features of Wagner’s many-faceted character: tasteless and callous humor, egregious cultural chauvinism, poor judgment, and a complete inability to exercise self-restraint or appropriate self-censorship. Without meaning to defend him against any of those charges, I believe that his essay in Aristophanic satire, however marginal, can provide an interesting window on the composer’s psychology and on the national conflicts of 1870, in which he participated so vigorously, if vicariously. Wagner’s sense of personal victimhood vis-à-vis the French remains the key to his response to the war, and there is no doubt that it was a profoundly exaggerated, even irrational, one. Nonetheless, he knew his “enemy” a great deal better than many flag-waving and saber-rattling German artists or writers of the day. Musical representations of awakening German national feeling normally involved heavy doses of counterpoint, chorale, turgidly serious (and perhaps “descriptively” bellicose) development, and general bombast—whether practiced at the level of Joachim Raff’s Vaterland Symphony (premiered in 1863) or, with more finesse, in Brahms’s neo-Handelian Triumphlied, expressly composed to celebrate the German victory over the French in 1870. Wagner practiced this genre, too (at least for a fee), in the Kaisermarsch composed to honor the proclamation of the Prussian king as Emperor Wilhelm I of Germany early in 1871. (Anton von Werner’s 1894 painting Quarters at a Base Outside Paris in 1871, in which uniformed Prussian officers in muddy boots lounge about a requisitioned salon entertaining themselves and their French hosts with good German lieder, has often been cited as an image of German Kultur imposing its allegedly inward spiritual values in this aggressive vein; see Figure 3.) But among his fellow Germans only Wagner, it is safe to say, would have contemplated a satire of the French on their own cultural ground, by adapting French operetta (however ineptly) to Aristophanic comedy.

Figure 3. Anton von Werner, Quarters at a Base Outside Paris in 1871, 1894. Oil on canvas (Berlin, Nationalgalerie).

As mentioned, he saw Aristophanes as greeting the decline of the Athenian golden age with a knowing smile, a philosophical resignation grounded in comic awareness. While Wagner took a more personal, more malicious pleasure in what he regarded as the decline of France in 1870, he also believed he was taking a broadly “philosophical” view—mocking not just the French defeat but also the perennial German “surrender” to French culture. At least, this is the gist of Wagner’s defense of his comedy, as we have seen. Just as Prussia and the other German states rallied against French political hegemony, Wagner rallied his followers against French cultural hegemony. The German Empire was born from the downfall of the French Second Empire; the Wagnerian cultural imperium soon to be founded in Bayreuth was likewise nourished in the atmosphere of German triumphalism of 1871. If Eine Kapitulation might at first seem like an inconsequential bad joke, it could also suggest that Wagner had at least some fleeting insight into the emergent power of an urban popular culture, the power of a completely non-Wagnerian music as parody and entertainment, epitomized in the Parisian operettas of Offenbach.

“Operetta is the vital theatrical question of our time,” a concerned provincial critic stated in the Schlesische Volkszeitung of 10 September 1878. “Just as the materialistic tendencies of our day have engendered it and encouraged it to thrive,” he continues, operetta in turn “has provided abundant nourishment to every impure and deplorable seed in the hearts of our contemporaries.” (Earlier in the same article, the writer expresses similar opprobrium toward the “sensual and salacious content” of Wagner’s own operas—“all of which are more or less concerned with the relation of woman to man.”) This provincial prudery is mocked by a more sophisticated Berlin critic, Robert Musiol, who quotes the Silesian journalist (“some sage village pastor or schoolmaster”) at length in his own reflections “On the Question of Wagner, Opera, and Operetta.”47 Yet while Musiol shares his provincial colleague’s low opinion of the aesthetic and moral value of the modern operetta, on the whole, he is equally cognizant of the potential significance of the genre, the potential influence of an emergent popular culture on the modern urban masses. “The messiah of the operetta is still to come.”48 For a brief moment, Wagner toyed with that idea, too.

In retrospect, the Franco-Prussian War can be seen as a dress rehearsal for the First World War, or rather a curtain raiser, though one that failed to alert Europe to the catastrophic dimensions, and consequences, of the “main act” to follow—Untergang on a scale that would scarcely inspire laughter. If Wagner had been a better reader of Aristophanes (the antiwar message, for instance), or had paid closer attention to Offenbach, he might have produced a rather different, perhaps more successful comedy.49 A postscript to Cosima’s diaries, entered by Daniela von Bülow, tells us that on February 12, 1883, the day before his death, Wagner had “asked Mama’s opinion on whether he should retain Die Kapitulation in the second edition of his works, since it had been received so stupidly even in Germany, and by no means understood by his friends, either.”50 In the case of his little “Aristophanic” musical comedy, he understood that he had to admit defeat. The tragedy is that he never really understood why.

1. Cosima Wagner’s Diaries, 2 vols., ed. Martin Gregor-Dellin and Dietrich Mack, trans. Geoffrey Skelton (New York, 1978, 1980), 1:266; entry of 4 September 1870. (Subsequent citations to this edition are given in the text and notes as CWD with date of entry only.) Compare also Wagner’s ebullient response to the fall of Orléans to Bavarian troops a month later: “That we should live to see this, the humiliation of the French nation! And on top of that a wife and a son—is it not a dream?” CWD, 14 October 1870.

2. On Léon Gambetta and his celebrated balloon journey across enemy lines from Paris to Tours, see also Rupert Christiansen, Paris Babylon: The Story of the Paris Commune (New York, 1994), 194-95, as well as the biography by Daniel Amson, Gambetta ou le rêve brisé (Paris, 1994), chap. 24, 192-200. Gambetta’s airship, named the Armand-Barbès, departed from the Place Saint-Pierre in Montmartre in the company of a second one named the George-Sand, at 11:30 a.m. on October 7, 1870, and arrived in the vicinity of Tours only after several close encounters with Prussian artillery.

3. The famous photographer Nadar, who is given a leading role in Wagner’s comedy, painted a portrait of Gambetta’s own airship, the Armand-Barbès, together with its companion, the George-Sand. This 1870 painting, housed at the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace in Le Bourget, France, is reproduced in John Milner, Art, War and Revolution in France 1870—1871 (New Haven and London, 2000), 82. The volume is a rich repository of visual documentation of the Franco-Prussian War, the siege, and the Paris Commune.

4. Wagner, who had already commented on Aristophanes’ resignedly comic perspective on the “decline” of Athenian political power (and culture) in Art and Revolution (1849), could have observed some parallels to the French situation in 1870-71 and the Athenian defeats and “capitulation” to Sparta and Persia in 405-4 BCE. On the latter, see, for example, Alan H. Sommerstein’s introduction to Lysistrata and Other Plays (London and New York, 1973; 2nd ed., 2002), xvi-xvii. Cosima recorded Wagner’s later remarks on Aristophanes as an observer and critic of Athenian political decline (CWD, 1 March 1877): “in the evening we read Peace to the end,…—it is enough to numb us with its genius: the Athenians went laughing to their downfall”; and 4 April 1877, regarding Plutus.

5. We know from Mein Leben that Wagner had read Birds upon first encountering the plays of Aristophanes in 1847.

6. See CWD, entries of 4, 5, 6, 22, and 23 February 1870. This interest in Aristophanes seems to have been suggested by a letter from Cosima’s half sister, Claire Charnacé, mentioned on 17 November 1869.

7. Kenneth McLeish, The Theatre of Aristophanes (New York, 1980), 52.

8. The essay appears in the collection Aus dem wahren Milliardenlande: Pariser Studien und Bilder, 2 vols. (Leipzig, 1878), and is reprinted with commentary in Friedrich Chrysander, “Max Nordau über Offenbach und die Operette,” in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 16 (4, 11 May 1881): cols. 279-86, 295-302. “Offenbach strikes me as being the Aristophanes of our times,” writes Nordau. “He shares with his Athenian predecessor the same high spirits, biting wit, fecundity, and the same superior Weltanschauung. But like Aristophanes, he does not write for children, and the charge of immorality that has been leveled against him by school headmasters can be quite simply answered by pointing out that satire is intended for mature minds, and that the inmates of boys’ and girls’ schools are better off reading their exciting stories of Indians in the Wild West than attending a performance of La belle Hélène” (cols. 282-83).

9. Queen Victoria’s daughter, the Crown Princess Victoria of Prussia, expressed this view (shared by many outside of France), writing to her mother a few days after the defeat at Sedan and the fall of Louis Napoleon: “May we all learn what frivolity, conceit, and immorality lead to!” “Gay and charming Paris!” she continues in the same didactic mode. “What mischief that very court, that still more attractive Paris, has done to English society, to the stage and to literature! It would be well if they would pause and think that immoderate frivolity and luxury depraves and ruins and ultimately leads to a national misfortune. Our poverty, our dull towns, our plodding, hardworking serious life has made us strong and determined; is wholesome for us.” Letter of 6 September 1870, cited in Christiansen, Paris Babylon, 162. Though writing from Germany, indeed as a member of the Prussian royal family, the Crown Princess seems to be speaking here for and about the English.

10. The altar of Dionysus, which stood in the center of the dancing floor or “orchestra” of the Theater of Dionysus, on the slope of the Acropolis in Athens.

11. The Hôtel de Ville did not have a balcony in 1870. Nonetheless, Wagner’s image of the Hôtel de Ville missing its upper stories forecasts, unwittingly, the fate of the building at the end of the Paris Commune some months later (May 1871), when, along with the Tuileries Palace and numerous other public buildings, it was gutted by fire.

12. Chapter 3, “The Theater of Dionysos” (38-49), in McLeish, The Theatre of Aristophanes, gives a detailed description of what is known about the theatrical space in which the comedies of Aristophanes were performed in Athens as well as what can be speculatively reconstructed. Wagner clearly took both a scholarly and practical interest in the design of the ancient Greek theater; his plans for the auditorium of the Bayreuth theater, begun shortly afterward, would adapt the classical amphitheater seating to the modern, indoor proscenium stage.

13. Nordau, “Der Pariser Aristophanes,” in Chrysander, “Max Nordau über Offenbach und die Operette,” col. 281.

14. Ibid.

15. Stephen Halliwell, introduction to Aristophanes, Birds, Lysistrata, Assembly-Women, Wealth, trans. Stephen Halliwell (Oxford, 1997), xix.

16. The issue of food assumed both practical and symbolic dimensions in the Prussian siege of Paris; the public fascination with Parisian responses to dwindling food supplies (alluded to in the role of the Parisian “rats” in Eine Kapitulation) reflects what might be viewed as a form of gastronomic warfare, considered especially apt for this particular campaign.

17. Victor Hugo returned to Paris after his extended self-exile on September 5, 1870, the day after the fall of the imperial government. After the 1848 Revolution Victor Hugo had been elected a member of the Corps Législatif and supported Louis-Napoleon in his initial bid for the presidency of a French republic. Hugo opposed, however, Louis-Napoleon’s 1851 coup d’état and the establishment of the Second Empire, after which he fled to Brussels and then spent most of the intervening years in exile on the Channel islands of Jersey and Guernsey until the fall of Napoleon’s government at the end of 1870. He briefly served as a deputy in the new National Assembly in 1871 and published an extended series of verses on the experience of the siege and the Paris Commune (L’année terrible, 1872).

18. The “flamboyant and buccaneering Gustave Flourens,” as Rupert Christiansen calls him (he had previously fought with the Greeks against the Ottoman Turks in Crete), led an attempted coup, together with fellow communist insurrectionary Auguste Blanqui, against the Government of National Defense at the Hôtel de Ville on October 31, 1870, just one week before Wagner came up with the idea for his comedy. Flourens and his associates formed a “Committee on Public Safety,” echoing the name of Robespierre’s notorious revolutionary body during the Terror. The group was disbanded before the night was out, following extensive vandalism and consumption of large quantities of food and wine. General Trochu and Jules Ferry were briefly imprisoned in the city hall, but were freed by members of the National Guard with whom they subsequently reentered the building through various subterranean passages to reclaim control of their government. “Then, like the finale of one of Offenbach’s operettas,” Christiansen remarks, “the 3 a.m. exodus from the Hôtel de Ville brought the government leaders to the portals arm-in-arm with the communards” (Paris Babylon, 207, citing also a contemporary account from the Illustrated London News). The episode is equally suggestive of elements in Wagner’s “operetta,” and most likely the mêlée at the climax of Eine Kapitulation alludes to it.

19. My Life, trans. Andrew Gray (Cambridge, U.K., 1983), 343.

20. After beginning Lysistrata in January 1874, they read Plutus (Wealth) and reread Peace in 1877 (4 April, 1 March), and returned to parts of Frogs in 1878 (6 October) and 1881 (11 April). As mentioned in note 3 above, the 1877 readings elicited remarks on Aristophanes as a “laughing” and “sublime” reflection of Athens and the Greeks at the moment of decline.

21. This may also be a function of the fact that he never got to the point of composing or producing the piece and thus was not forced to work out practical dramaturgical issues.

22. See Eine Kapitulation, in Richard Wagner, Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen, 10 vols. (Leipzig, 1887-1911), 9:13, 23, and 35-36 (henceforth GSD in both text and notes). In the second instance Wagner puns on the imperative “Vole au vent!” (Fly with the wind) and the familiar French term for a puff-pastry shell (vol-au-vent), anticipating further gastronomic “jokes” that make light of the famous famine visited on Paris by the German siege in the last month of the war.

23. Stephen Halliwell’s description of the treatment of the chorus in the parodos (its “movements are always choreographed to represent a particular kind of action, condition, or mood” characteristic of the group represented) would apply to the first appearance of the Chorus in Eine Kapitulation as members of the National Guard, vigorously marching and singing. See Halliwell introduction, Birds, Lysistrata, Assembly-Women, Wealth, xxxiii.

24. Eine Kapitulation, GSD, 9:27.

25. As Wagner would have been aware, the comedies of Aristophanes frequently involved such “meta-theatrical” play with the boundaries of stage, audience, and theatrical illusion, most obviously in the generic institution of the parabasis (the direct choral address to the audience), but also in the form of self-conscious allusions to the technology of the stage, such as the skene itself or the crane used to lift actors on and off it. On this dimension of Old Comedy, see Niall W. Slater, Spectator Politics: Metatheatre and Performance in Aristophanes (Philadelphia, 2002).

26. “Falsche Anklage! — Nichts kapituliert! — Wir bringen euch das internationalste Individuum der Welt, das uns die Intervention von ganz Europa zusichert! Wer ihn in seinen Mauern hat, ist ewig unbesieglich und hat die ganze Welt zum Freund! — Erkennt ihr ihn, den Wundermann, den Orpheus aus der Unterwelt, den ehrwürdigen Rattenfänger von Hameln?” Eine Kapitulation, GSD, 9:35.

27. The Garde Mobile—the mobile guard, a military unit—hardly belongs in this list, but here, as earlier in the play, Wagner is drawn to pun on the term in connection with the popular ballroom dance establishment, the Bal Mabile.

28. Eine Kapitulation, GSD, 9:40-41.

29. Probably the Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater or the Viktoria-Theater. See Ruth Freydank, Theater in Berlin: Von den Anfängen bis 1945 (Berlin, 1988), 245-323. The index of opera and musical theater performances in the Neue Berliner Musik-Zeitung 23 (1869) lists about twice as many performances and/or individual productions of Offenbach works than for any other theatrical composer. Most of the titles listed were presented at the Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater.

30. The text had initially been submitted anonymously, via Hans Betz, to “the larger of the Berlin Vorstadttheater” (minor or suburban theaters), as Wagner noted in the preface to the published edition (GDS, 9:5). Although it is not possible to say for sure whether he would have had the “book” attributed to him had it come to a performance, he did include this text in the first edition of his collected writings, which he already began to prepare for publication in 1872.

31. Prior to that, Richter had tried to offer excuses of his own: “He declares that the reason Betz does not reply to him is undoubtedly that he thinks Richter needs money and has therefore started to compose!” CWD, 16 December 1870.

32. See CWD entry from 24 June 1873 with reference to the preface and plans to publish the text of Eine Kapitulation, called in the diaries either Die Kapitulation or Nicht kapituliert: the latter version presumably referring to Ferry’s speech upon the providential arrival of Offenbach. Cosima quotes Wagner’s own sense of his questionable judgment in printing this text, as in his decision to republish “Judaism in Music” several years earlier: “He says he must always be doing things of which I cannot entirely approve, yet… I never reproach him.”