In his lectures on Richard Wagner at the University of Vienna held during the 1903-4 academic year, the music historian Guido Adler felt obliged to confront the claims in Wagner’s notorious essay “Das Judentum in der Musik” (Judaism in Music). He characterized them as reprehensible political commonplaces, part of a social tirade unbecoming a great artist. Adler and his audience were keenly aware of the electoral successes of Vienna’s charismatic Christian Socialist mayor, Karl Lueger, who during the 1890s had deftly exploited a potent populist and political anti-Semitism in the city.1 Adler, who was born a Jew, conceded that the sort of political platitudes Wagner used could inspire modernity’s sheep-like masses. But he added no further comments, closing with this thought: “I would prefer to leave to others to speculate on any further conclusions. On such questions, the sort of irritability that, unfortunately, is so morbidly aroused must not play a role, but rather open, brave opposition, calm debate, and thoughtful consideration of all points of dispute. Let us place our confidence in the judgment of history. That judgment, however, must not be based on false ‘foundations’ derived from false premises that lead to monstrous conclusions.”2

The judgment of history about Wagner’s anti-Semitism and whether its influence, particularly on Germans and Hitler, contributed significantly to Nazi Germany’s “monstrous conclusions”3 remains open to much ongoing debate.4 The well-publicized ban on Wagner performances in Israel continues to focus our attention on Wagner’s role in modern European history and the historical significance of his anti-Semitism.5 When David Stern was appointed director of the Israel Opera in 2008, he indicated that he would honor the Wagner ban as long as Holocaust survivors remained alive, out of respect for their feelings.6 His decision reflects a prevailing consensus, not only in Israel, that Wagner was a key inspiration for modern German anti-Semitism, that he influenced Hitler, and that enthusiasm for Wagner helped justify the death camps for those Germans who created them, as well as for those who stood by in silent agreement. This belief persists whether or not one believes that links between Wagner’s anti-Semitism and Nazi ideology can be read outside of Wagner’s prose and conversations, and are located, tacitly and overtly, in the music, texts, and plots of the operas and music dramas.7

Disagreement over the appropriateness of the ban derives only partially from disagreement over the historical claim that Wagner was a decisive influence on the Nazis and the German embrace of Nazism. Wagner died in 1883, long before there were Nazis and even before Hitler was born. The historical debate has therefore centered on the originality and influence of his anti-Semitism. How unusual and persuasive was Wagner in the admittedly highly anti-Semitic context of late nineteenth-century Europe, in which anti-Semitism had long been a historical reality? Does anti-Semitism, cloaked in the seductive beauties of Wagner’s works, emerge as symbol and allegory? If so, was it recognized as such in the past and is it still perceptible on the stage and audible in the music? If anti-Semitism is understood as an essential component of the drama and the musical fabric, then the historical debate shifts from Wagner the personality and ideologue to the character and impact of Wagner’s art.

Wagner’s anti-Semitism first became the subject of heated controversy in 1869 when the composer republished his already notorious “Judentum” essay under his own name, in a slightly revised form with an appendix. The debate regarding its significance and influence has continued with intensity since 1933. Yet despite extensive work on Wagner’s influence in Wilhelmine Germany, on Hitler, and on twentieth-century German anti-Semitism, there has been comparatively little investigation on how Jews in German-speaking Europe reacted and responded before World War II to Wagner the anti-Semite, or even how they reacted (as Jews) to Wagner the writer and composer.

Wagner’s unparalleled success not only in Germany but throughout Europe and North America from the mid-1870s on, and his popularity among Jews, particularly after 1870, forced German-speaking Jews to confront fundamental issues of their self-image and status in civil society beyond the confines of legal emancipation.8 Wagner was more than a composer who claimed for himself the mantle of Beethoven in the history of music. Wagner became a potent cultural force and symbol after the unification of Germany, when the success of Jews in integrating and assimilating into German society and culture became increasingly palpable and visible.9 Not surprisingly, the confrontation with Wagner and Wagnerism among Jews coincided with revivals in Jewish nationalism (including Herzl’s Zionist project), the acceleration of a Jewish identification with “Germanness,” and the deepening of the pre-1848 Jewish embrace of the ideal of a transnational aristocracy of culture that transcended politics and religion.10

Since after 1870 political anti-Semitism became associated with Wagner, and since Wagner and his followers were viewed in liberal circles as “arousing” the “morbid irritability” of the day that anti-Semitism represented, educated Jews could not easily avoid Wagner. One of Wagner’s signal achievements was his success in generating a self-serving but persuasive and widespread account of music history. The character of Jewish responses to Wagner, both adoring and critical, helped lend twentieth-century modernism its character, particularly modernism’s construct of language and form. Indeed, the reaction against Wagner, in part fueled by the need to counter the aesthetic underpinnings of Wagner’s astonishing popularity (and therefore indirectly his ideas, anti-Semitism among them) helped spur a fin-de-siècle “rediscovery” of Mozart and a subsequent renaissance of interest in Offenbach.11 Only after 1945 did Wagner’s role as an anti-Semite inspire an attempt to reconsider the way the modern history of music since Bach is understood.12 Unfortunately, this post-World War II revisionism resulted in only halting and marginally successful reevaluations of the achievements of the primary victims of Wagner’s version of history and anti-Semitic polemics, Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer.13

The most powerful argument against Israel’s ban, however, invokes none of these issues about cultural reception. Rather it concerns the merit, efficacy, and unintended consequences of official or consensual censorship. By implicitly asserting Wagner’s historical responsibility, the ban tacitly avoids confronting two common underlying assumptions: that the Germans under the Nazis were alone responsible for the Holocaust and that the Nazis represented the culmination of a unique, continuous historical trajectory of anti-Semitism in German-speaking Europe in which Wagner played a crucial part.14 But if one questions the historical assumptions linking Wagner and the Holocaust, arguments against the ban assume a different aspect. By endorsing the assignment of historical responsibility for the extermination of European Jewry, even symbolically, to Wagner, the ban may have the effect of falsifying history.15 The consequence for current and future generations in Israel is disastrous, for the real causes of the Holocaust become obscured, distorted, and replaced by a facile, convenient, and misleading formula. Any distraction of attention from the historical circumstances that actually made the death camps and Einsatzgruppen possible and astonishingly efficient is dangerous. Genuine respect for the survivors might then argue against a ban on Wagner, even if the survivors themselves, for a complex of understandable reasons, viscerally accept the validity of the Wagner-Hitler equation.

Wagner attained a significant Jewish public from the start of his career. Banning Wagner shields Israelis from the historical record of the response among Jews to Wagner, in his lifetime and after. What were the ways in which Wagner influenced not only German and European Christians but also Jews in Germany? This aspect of Jewish history, suppressed and disfigured by the ban, demands recovery. In the process of recovery, affirmative and not defensive reasons to produce, play, and listen to Wagner, in Israel as well as elsewhere, can emerge that do not require a rationalization of the historical record and do not tacitly apologize for the monstrous consequences undeniably present in all forms of nineteenth-century European anti-Semitism.16

There were three distinct eras of debate between supporters and critics of Wagner in German-speaking Europe between 1870 and 1945. In each era Wagner’s anti-Semitism played a crucial role. The first of these controversies erupted soon after 1870, in the wake of Wagner’s 1869 republication of “Judaism in Music,” the German victory (over France) in 1870, German unification, and the 1870 Viennese premiere of Die Meistersinger. A public exchange between Wagnerians and anti-Wagnerians continued throughout the decade (which witnessed the opening of Bayreuth) and continued until shortly after Wagner’s death in 1883. The second era began at the turn of the century and culminated in 1913, when Bayreuth’s right to continue its exclusive hold on Parsifal was openly contested. Unauthorized performances in New York, Amsterdam, and Monte Carlo became a subject of controversy.17 That debate revealed a fin-de-siècle generational divide. The young reacted against the Wagnerian enthusiasm of the 1870s, both in art and politics. It was in this era of reaction that Guido Adler gave the lectures cited at the beginning of this essay. The third era of intense controversy lies beyond the scope of this essay and has been the one most closely scrutinized by modern scholarship. It began in the late 1920s and accompanied the rise of Hitler and the establishment and defeat of Nazi Germany.18

The Viennese premiere of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger took place on February 27, 1870. In 1871, in the wake of the opera’s success, Peter Cornelius published an essay in the Viennese Deutsche Zeitung, “Deutsche Kunst und Richard Wagner,” arguing on behalf of a pan-German campaign for the support of Bayreuth. With Die Meistersinger, maintained Cornelius, Wagner had realized his destiny and historical mission, filling a longstanding vacuum by providing the German people with a contemporary artistic and communal expression of the modern German spirit. Having experienced the power of Die Meistersinger firsthand, the time had finally come for the Viennese to embrace the creation of Bayreuth.19 Only two years earlier Wagner had republished “Judaism in Music” under his own name, with an appendix excoriating a Jewish conspiracy against him. Did Cornelius’s call for a populist embrace of a Wagnerian “Germanness” include German Jews in Vienna or anywhere else?

Few Jews were regular readers of the pan-German and frequently anti-Semitic Deutsche Zeitung, but in 1870 Vienna had more than its fair share of Jewish Wagner devotees. The premiere of Die Meistersinger made this abundantly clear. Daniel Spitzer (1835-93), the great Jewish Viennese satirist (who himself briefly wrote for the Deutsche Zeitung), described the premiere. A conflict broke out between supporters and detractors. The performance took place, as Spitzer’s review acknowledged, in front of an audience that knew Wagner held a Jewish clique responsible for hindering his career. The irony, Spitzer observed, was that among those in the audience shouting on behalf of Die Meistersinger, the quintessential articulation of German national pride, there appeared to be a large number of unmistakably Jewish Viennese opera lovers. As Spitzer put it, coyly referencing Wagner’s essay, “One could not succeed in getting beyond the verbal insults during the performance, where, as expected, the Wagnerians often lost all sense of proportion, so that a perfectly decent derisive whisper of ‘Mendelssohn’ was followed by an even more crude insult of ‘Meyerbeer’ being thrown in one’s face. The confessional character of this musical war ultimately receded, so that one could see Christian-musical Germans hissing, and in contrast, possessors of noses bent heavily by the burden of Semitism applauding.”20

The most vocal skeptics and critics at the premiere turned out to be non-Jews, well informed and articulate connoisseurs who took exception to Wagner’s form of theater, poetry, and music. One such critic was Ludwig Speidel (1830-1906), who noted with considerable amazement that “Wagner treats the Hebrews like mangy dogs and in return they follow with tails between their legs and lick his hands with pleasure. They are deaf to the gentle alluring calls of Mendelssohn and the sharp whistling of Meyerbeer. Certainly these paradoxical phenomena belong to the amazing effects that derive from Wagner’s personality.”21

The reaction of Viennese Jews to Wagner’s music was not exceptional in German-speaking Europe, despite the composer’s public standing as a committed anti-Semite. At the conclusion of the first production of the Ring at Bayreuth in 1876, George Davidsohn, critic of the Berlin Börsen-Courier and head of the Berlin Wagner Society, stood up and delivered an off-the-cuff public encomium to Wagner, precipitating ovations that forced the composer to the stage to address the audience.22 Davidsohn (1835-97) was Jewish.23 Again, Spitzer was there: “The house was full… and even the prosperous Wagner-Semite from Berlin was not missing, who, despite the attacks by the music monopolies against their Jewish competitors, could be found in the prominent presence of the happy Master, whose long Talmud-Sniffing nose reveals clear signs of an earlier racial affinity. It is said that Wagner fears most of all the discovery of his own Jewish ancestry and dislikes when he sees his name shortened to R. Wagner because he fears it could be read as easily to mean ‘Rabbi Wagner.’”24

By the 1870s three facts seemed clear: Wagner was an outspoken anti-Semite, his art was inextricably bound up with a new German self-definition, and German Jews were among the most enthusiastic consumers of Wagner’s work. Writing in response to Cornelius’s essay on “Richard Wagner and German Art” in 1871, Speidel, despite deep misgivings about Wagner’s aesthetics and morals, conceded that one could not argue with success: “The German people see in Wagner’s operas its contemporary musical ideals realized, and whoever wishes to take that from them—assuming that were even possible—would be taking a piece of soul from the bodies of these people. If art, above all music … belongs even a tiny bit to the substance of Germanness, Wagner’s substance cannot be separated any longer from the essence of the German … against my own feelings … the conclusion is inescapable: The substance of Richard Wagner can no longer be separated from the substance of the German.”25

In light of the Germans being defined in Wagnerian terms and therefore connected in substance to Wagner’s construct of anti-Semitism, how could German Jews embrace Wagner so enthusiastically?

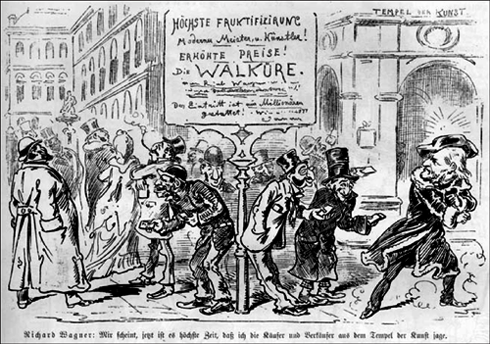

The implausibility and irony of a Jewish enthusiasm for Wagner did not escape Wagnerians, anti-Wagnerians, or anti-Semites. In the humor magazine Wiener Luft (associated with Figaro, the publication with which Spitzer first gained his reputation as a satirist), the texts and cartoons from the 1870s show both a persistent exploitation of popular anti-Semitism and a thoroughgoing skepticism about Wagner—his delusions of grandeur, the bizarre character of the content of the Ring with its dragons and giants, and the excessive cost of the spectacle. Wagner’s own hypocritical attitude to money, power, fame, and Jews is underscored in a cartoon from the spring of 1877, when Die Walküre was premiered in Vienna (see Figure 1). Jews are depicted, gathered outside the Opera House. Some well-heeled types are in the background. A sign indicating the sale at wildly high prices for the performance is placed above a set of shabby Jews in the foreground hocking tickets, seeking to make a profit. The phrase “The Temple of Art” is placed on the Opera House above an idealized caricature of Wagner looking shocked and angry. The caption reads “Richard Wagner: ‘It appears to me that it is high time that I chase these buyers and sellers from the Temple of Art.’”26

In a caustic review of the 1877 performance, Spitzer shredded Walküre’s poetic language, the story’s pretensions, and any claim to dramatic tension or symbolic meaning. Spitzer took aim once again at the Jewish enthusiasm for Wagner. Poking fun at Siegmund’s Act 1 declaration of various incognitos he must refuse (Friedmund, Frohwalt) or accept (Wehwalt), Spitzer suggested three more modern equivalents in use in Vienna that would sound even more apt: Friedmann, Fröhlich, and Wehle—all familiar Viennese Jewish last names.27

Figure 1. An 1877 cartoon of a hypocritical Wagner eying Jewish scalpers with disapproval.

Non-Jewish observers, particularly Wagnerians, may have marveled at the Jewish embrace of Wagner, but at the same time they used Wagner’s anti-Semitism to explain away criticism of the master of Bayreuth, as he himself had tried to do. If critics (often identified falsely as Jews) were opposed to Wagner, it was merely on account of Wagner’s politics, not his art, they claimed. Yet as Wagner’s popularity grew throughout Europe (particularly in Vienna after Wagner’s triumphant appearance there as a conductor in 1875), there was increasing enthusiasm for his music among Jews.

The Jews’ marked overcoming of hesitancy and skepticism was subject to scathing contempt: conversion to Wagnerism seemed as pathetic an attempt to erase the indelibility of one’s identity as a Jew by conversion to Christianity.28 It was as if Jews, by becoming ardent Wagnerians, were intent on disproving Wagner’s assertion of their essential lack of artistic feeling, their incapacity to recognize and experience the aesthetic. Yet by their actions they actually underscored among anti-Semites Wagner’s explicit fear of a “Jewish” skill at mimicry and imitation, as well as an alleged “Jewish” instinct for mere fashion. The Jewish Wagnerian became the ideal type of the insecure parvenu seeking to camouflage his essential vulgarity by proclaiming himself in the forefront of a new and fashionable artistic movement.

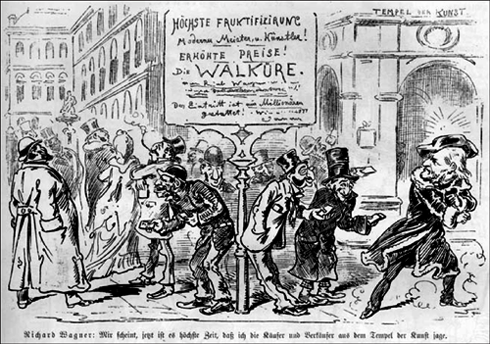

Once again, the Wiener Luft weighed in. On the occasion of the 1879 Viennese premiere of Götterdämmerung, the front page of the November issue sported a cartoon showing three small caricatures of Jewish men (see Figure 2). Two, on ladders, are placing a wreath on an outsized bust of Wagner while the third reads an address to the Master. The caption: “Even the most embittered of Anti-Wagnerians permit Richard Wagner to call himself a genius after the performance of Götterdämmerung.”29 Now that it was socially acceptable, joining the Wagner cult would redeem the Jewish capacity for aesthetic judgment. The parvenu Jew, metaphorically speaking, jumped on the bandwagon in a desperate but useless attempt to disguise his true and ultimately unalterable character.

The Jews were trapped. The judgment of serious critics of Wagner (Spitzer, for example) was impugned because their attitudes were ascribed to defensiveness, a desire for revenge, and a philistine but characteristically Jewish adherence to established and conventional norms of judgment.30 Given Wagner’s views and the attitudes of the most enthusiastic of his anti-Semitic followers, particularly those closely associated with Bayreuth, Jewish Wagnerians were either viewed with bemusement or held in contempt for their evident self-loathing. The contempt on the part of Wagner and his circle was so acute that they exploited without apology the enthusiasm of their Jewish followers near and far.31 Wagner’s inner circle knew they had little choice. As early as the 1850s, Hans von Bülow acknowledged, with considerable regret, the importance of the Jewish urban middle class as a crucial audience for music and theater, and therefore an important source of patronage for artists and institutions, including Wagner. By the 1870s the visible significance of the Jewish audience was widely recognized (Figure 3).32

Spitzer was among the most eloquent Jewish cultural critics to espouse a normative anti-Wagnerian view of art, in which language and music were distinct and independent, albeit related, entities. Spitzer was born into a Jewish Moravian family; his father founded a printing firm that produced high-quality art reproductions. Unlike many of his fellow intellectuals, Spitzer remained Jewish. His wit and satire took no prisoners; even to Jews he was merciless. Against anti-Semites he used his unabashed willingness to identify with the masses of poor, uneducated, and unassimilated Jews of Vienna. From his grandmother he learned Yiddish, which he later used to satirize Jews in Figaro under the sarcastic pseudonym Itzig Kneipeles. His friendship with Brahms led to the rumor, he joked, that Brahms, too, might be a Jew.

Figure 2. An 1879 cartoon of Jews paying tribute to the mighty Wagner.

Yet Spitzer was entirely acculturated, inactive in the Jewish community, and as best one can make out, a skeptical agnostic, if not an atheist.33 He acquired a strong, classical, Gymnasium education and a law degree. Like Eduard Hanslick, Spitzer’s idealized construct of the German was located in the literature of Weimar Classicism (Goethe and Schiller) and in music from the era of Mozart and Beethoven. As his love of Greco-Roman culture and Tristram Shandy suggests, there was little in Wagner to attract Spitzer. For him, music was an autonomous art, distinct from poetry and prose. The bombast of Wagner’s musical and linguistic rhetoric made the Master an easy prey—as did his endless alliteration and faux archaism, and his penchant for rhetorical questions. Commenting on lines sung by Gutrune in Act 1 of Götterdämmerung, Spitzer singled out the “entirely meaningless” words tapfen and ergannt he saw in the 1876 publication of the libretto as probable printing errors rather than bizarre versions of the familiar words tapfer and erkannt. Despite desperate efforts of fanatical orthodox Wagnerians to justify this odd language at any cost, might these not be merely overlooked printing errors? If so, Spitzer mused, might one not be compelled to regard “half” of the poetic text to be the work of a poor copy editor rather than that of Wagner?34

Figure 3. An 1874 Viennese caricature of Jewish patrons at the opera.

Spitzer demolished the ethical and symbolic content of both the Ring and Tristan.35 About Walküre, Spitzer argued that “the action on the stage inspires our disgust, the recitatives are without character, and the crippled verses (that ought have first been admitted to an orthopedic hospital) offend our ears, and the orchestra bores us with long-winded identifying explanations of the plot and the words.”36 Language, in the end, revealed the pretentious vacuity of Wagner. Spitzer opened his Walküre review with a nearly untranslatable parody using the letter W: “Weh, wie wenig Wonne ward mir wanderndem Wiener Spazierwalt [sic] durch Wagner’s ‘Walküre’!37 This, my dear unlucky new high German reader, is the famous now long dead alliteration that the Master has brought back from the grave where it has rested for a thousand years. In these deadly mechanical rhymes his talkative gods and heroes hold their endless conversations. After one has listened for a while one begins to hear these ghostly rhymes clatter as if bones of the dead were banging against one another. But these heroes are, despite their shriveled language, not the old German heroes who sang together brandishing shields and swords but… [represent rather] the triumph of merely boring parliamentary habits.”

In Spitzer’s view, Wagner’s pseudo-archaic recasting of myth revealed the worst of modernity. Wagner’s ambition to herald the future, to critique a corrupt civilization, and to offer an idealized universal worldview resulted in precisely the opposite: a spectacle of contemporary moral and ethical self-deception and confusion. The telling symptom was Wagner’s own invention, the synthesis of bad language and ugly music. “No melody disturbs the elevated monotony of this work of music,” Spitzer concluded.

As if to cast further doubt on Wagner as a serious and revolutionary thinker, Spitzer highlighted Wagner’s prowess in publicity, money raising, and self-advertisement. These unmasked Wagner’s grandiose ambitions as egregious examples of crass contemporary commercialism. Wagner’s musical theater, despite its claim to endless melody, seemed purely about mere spectacle and effect, a cheapening of musical, literary, and philosophical traditions.38 After seeing the last part of the Ring, Spitzer concluded that “with Götterdämmerung one finally has survived the Ring of the Nibelung, this tiresome Edda travesty in which the devoted listener is presented not with a meaningful epic, but manipulated illusions; instead of something wonderful, something contradictory; instead of power, vulgarity; instead of magical sounds, incomprehensible gibberish; and instead of the naïve, the philosophy of Schopenhauer”—a claim that Spitzer went on to demolish in an effort to rescue Schopenhauer from Wagner’s cheap version.39

At the crux of the debate about Wagner during the 1870s were questions that would resurface in every subsequent controversy. Why was Wagner so fashionable? What did Wagner mean to communicate in music and poetry? Were the roots of his success his greatness as a musician (and poet) or the consequence of debased cultural trends and fashions manipulated to generate a delusional escape from reality that facilitated an alluring reductive nationalism, replete with anti-Semitism? From the 1870s on, responses to these questions were incongruous and contradictory. Those who were Jews or viewed as Jews within German-speaking Europe knew that Wagner, the anti-Semite, had become the symbolic representative of a modern German civilization. Some, like Spitzer, attacked Wagner for undercutting noble Enlightenment standards of German culture and true learning—Bildung—the arenas of achievement Jews used to establish their place in the non-Jewish mainstream of society. Others embraced Wagner as the very epitome of modern culture and progress, as modernity’s most powerful expressive voice, its equivalent of Shakespeare, Goethe, and Beethoven.

Guido Adler was a loyal subject of the Habsburg monarchy in the manner best articulated by his better-known younger contemporaries, the writers Franz Werfel (1890-1945) and Joseph Roth (1894-1939), who, like Adler, were of Jewish birth.40 Culturally, Adler was a German chauvinist. But he was also an optimist who believed in the power of culture, reason, and high art to engender tolerance, as well as ethical and political progress. A close friend of Gustav Mahler and one of the founders of modern musicology, he argued that despite Wagner’s biography, political views, and anti-Semitic writings and pronouncements, the artistry and evocation of the “purely human” in his music would triumph in the course of time. The emotions Wagner’s work evoked might be unusually powerful, sensual, and irrational, but they sparked a catharsis in which the aesthetic power and beauty of the music cleansed the irrational (e.g., anti-Semitism) and “transfigured and ennobled” the listener. This, for Adler, was precisely the consequence of encountering the great works of art that had passed the test of time.41

Adler’s 1903-4 lectures on the twentieth anniversary of the composer’s death were designed to rescue Wagner’s legacy from the radical nationalist and racialist orthodoxies energetically propagated by Wagner’s epigones at Bayreuth, including Cosima Wagner, whose anti-Semitism had become more virulent and essentializing in the twenty years since her husband’s death.42 History became the instrument by which Adler sought to counter any continuing radical political appropriation of Wagner. Wagner was no longer relevant to politics, only to art. Adler distanced Wagner from the contemporary by elevating his status and rendering his artistic achievement as the only subject worthy of analysis: “Today the struggle over Wagner’s art is over; the art has won. We no longer have to speak for it, much less against it. We only have to speak about it.”43

A retrospective reading of German history that reverses history by starting with the Holocaust has shaped our judgments about the past.44 This is particularly evident in recent scholarship on Wagner’s polemical writings and anti-Semitism.45 From this perspective, Adler’s optimism in 1903 and 1904 regarding Wagner’s future reputation, reception, and influence seems starkly naïve. It reads, in retrospect, like a caricature of a familiar self-delusion all too prevalent among highly acculturated intellectuals of Jewish origin in German-speaking Europe at the turn of the century.

Inherent in the historical critique of Adler’s outlook is a contradiction. On the one hand, Adler, lulled into complacency by his own success, failed to see the proverbial handwriting on the wall: the pernicious influence Wagner would continue to have on politics and culture. Assessing Adler in this way assumes a trajectory that connects Wagner to Hitler and the “Final Solution” and assigns a key causal role to art and culture in shaping political realities. Another interpretation, which Adler’s case supports, is to acknowledge the weakness of culture in history. Cultural achievement and refinement, even when acknowledged by official status and public recognition, were inadequate social protections against radical, racialist, anti-Semitic politics, even for exceptional Jews like Adler. Jews in post-1870 Germany and the Habsburg monarchy (and later, inter-war Austria) who relied on culture and learning as routes to stable social integration and assimilation were shocked by the events of 1933 and the Anschluss of 1938. But despite the ubiquity of anti-Semitism around him, Adler, like so many of his distinguished Jewish contemporaries, sensed no fundamental instability for Jews, in part because he had no doubt about the significance of culture both in history and in contemporary society. Precisely for that reason he felt compelled to attempt a major revisionist interpretation of Wagner. The debate over Wagner’s legacy seemed an important public issue.

One needs to differentiate to whom the label “Jew” in the polemics beginning in the 1870s actually referred. Adler and his older colleague Eduard Hanslick (1825-1904), for example, no longer considered themselves Jews and were not officially part of the Jewish community.46 However, a racial definition of Jewishness was based on descent and lineage. It rendered being Jewish indelible and impervious to conversion. The political and cultural currency of this view owed a considerable debt to Wagner.47 In late nineteenth-century Vienna, Adler and Hanslick were not legally Jews, but socially, except in refined liberal circles, they were dismissed as Jews, baptism notwithstanding.48 Adler, who converted for practical reasons, never denied his social status as a Jew. However, being a rationalist and a devotee of science, he rejected all religion.49 He opened his memoirs by offering the reader a statement he had penned in 1928 regarding his “religion”: “Awe for God, respect for all faiths insofar as they reflect moral laws and ethical norms, love of one’s neighbor, love of nature, the cherishing of every nation … in the criticism of every national sense of superiority… in the prizing of all work on behalf of mankind, as well as art and science.”50 No credo could have been more redolent of a tolerant, enlightened, liberal cosmopolitanism.51

Hanslick went well beyond Adler’s admirable and ardent humanism.52 From the point of view of a Holocaust-inspired teleology, his path is instructive about the limits of assimilation. His mother had been Jewish, but she converted at the time of her marriage and raised her son as a Catholic. Therefore Wagner’s suggestion that Hanslick was Jewish was simply false.53 But for Wagner and a large segment of contemporary anti-Semitic ideologues, being Jewish was not a matter of confession and religion, but one of race. If the noble and humanistic sentiments Adler located as the essence of Wagner’s artistic achievement were to triumph, that victory depended on how successfully one could counter Wagner’s own racialist polemics.

Adler sought to inspire a radical shift in the interpretation of Wagner by minimizing Wagner’s historical originality. After placing him within a tradition of musical drama that dated back to the Renaissance, Adler explored Wagner’s debt to Romanticism. Most radically, given his regard for Mahler’s collaborations with Alfred Roller at the Vienna Court Opera, Adler called for a break from orthodoxies of interpretation and for a constant renewal in staging, so that the works might speak powerfully, as art alone, to new eras.54 With Mahler and Roller’s pioneering Viennese productions in mind, Adler called for a philosophically based symbolic revisionism in the way Wagner’s work was presented on stage, subordinating its naturalistic and narrative surface.55 Adler rejected Wagner’s normative view that music was inevitably tied to speech. For Wagner, music represented at one and the same time the origin of language and its historical fulfillment. Hence the integration of music with ordinary language became a historical imperative. Adler’s critique appropriated an earlier anti-Wagnerian argument about the unique character and autonomy of music vis-à-vis language. Adler’s historical method, unlike Wagner’s, eschewed obvious historical teleology. In explicitly anti-Wagnerian aesthetic terms, and despite the Master’s intentions, Wagner’s music, for Adler, was great.

By rendering Wagner not a contemporary phenomenon but a historical one, Adler stripped the political writings of all but biographical significance. They were, he argued, flawed by their lack of clarity and by historical errors. As Adler saw it, Wagner had achieved canonic status only as a composer, not as a thinker or even an innovator. In the canon he was one among many equals. The Ring, Adler argued, could not be viewed as literature. Only in combination with music could it be construed as comparable to literary drama. And Adler, deftly through deflection, rejected the idea that one might read contemporary political anti-Semitic stereotypes into the Ring. Adler explicitly argued that the centrality of gold and the obsession with the power of money that Wagner placed in the foreground had their root in ancient Nordic and German sources, in pagan mythic traditions (where there was no awareness of Jews and Judaism) in which money was defined as the ultimate source of evil. The overarching message of the Ring was not even radical or national. It was at once bourgeois and universal: the exclusive power of love between a man and a woman (e.g., Siegfried and Brünnhilde) to triumph over the pain and suffering of life. Wagner’s meaning was philosophical, not political. Adler denied Wagner the prophetic status he had so assiduously cultivated during his lifetime.56

As Adler’s strategy revealed, by 1900 Jewish Wagnerians like Adler, inspired by the experience of Wagner’s music in the theater, struggled to circumvent the political implications of Wagner’s ideas, particularly anti-Semitism. This is powerfully and poignantly revealed in the experience of the young Ernest Bloch. Born in 1880 in Geneva, Bloch studied composition in Frankfurt and Munich between 1896 and 1903. He became an enthusiastic Wagnerian, spellbound particularly by Siegfried, Götterdämmerung, and Die Meistersinger. Wagner’s music communicated the idealized essence of love and human solidarity. The impact was more than vague and general: Wagner helped define the meaning of intimacy. Writing to his fiancé in 1903 after hearing Götterdämmerung, Bloch confessed that the “least significant note of that immense genius, Wagner, can better serve to reconcile us than all the phrases … but shall I let it…?”57 Writing to her eight years later from Berlin, Bloch lamented, “I regret that you are not here … and now I have the ardent desire to listen once again to Wagner with you, in this country.”58

A seminal confrontation with Wagner occurred in the years between 1911 and 1916, when Bloch decided to embark on works known as the “Jewish Cycle,” including three Psalm settings (1912-14), the Israel Symphony (1912-16), the Three Jewish Poems (1913), and last, Schelomo, the Hebrew Rhapsody for cello and orchestra (1915-16). He was inspired by encounters with the journalist Robert Godet (1866-1950), Debussy’s friend and the translator of Boris Godunov, with whom he corresponded about anti-Semitism, and by his reading of H. S. Chamberlain’s notoriously anti-Semitic The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century (1899). Godet led Bloch to rethink his relationship to his Jewish identity and his allegiances as a composer. For Bloch, Wagner demonstrated that, in order to communicate universality, composers needed to sense membership in a particular national community. In 1911, Bloch studied in close detail the score of a work dear to his heart, Siegfried, finding it once again utterly beautiful, admirable, and grand. In the process Bloch resolved to assert his solidarity with the Jewish nation through music. Writing to his close friend Edmond Fleg (a Jew and the librettist of Bloch’s 1910 opera Macbeth), Bloch confessed that while listening to Die Meistersinger in Germany he felt closer to humanity—the same feeling he had when he played Bach and Beethoven. When Hans Sachs addressed the crowd in the third act, Bloch sensed Sachs was speaking to him as well.

But Bloch admitted to Fleg that “we are not French … we are also neither German, that is true, but our profound Jewish sensibility is closer to the complete realization of humanity which is German music than to the pretty musical contours of French music.”59 Writing in 1911 to a new-found friend, the Italian composer Ildebrando Pizzetti, Bloch reiterated that he had nothing in common with “French garb” but “contrary to Wagner, who said to the Jews ‘Cease being Jews, in order to become fully human with us,’ I think, I believe, I am convinced that it is only by becoming once again fully Jewish that the Jews will become fully human.”60 Wagner’s explicit anti-Semitism and his conception of music’s place in the formation of community led Bloch to reinvent himself as the modern artistic voice of the Jewish people so that Wagner might be proven wrong.61

For Jewish Wagnerians, the will to come to terms with the seeming irreconcilability between Wagner’s art and his politics did not end with the rise of Hitler. Consider two anecdotes from the early 1940s. In 1940, a thirty-four-year-old Leipzig Jew, without Gymnasium or university education, boarded with his wife and two small boys a train to Genoa, from which they would sail to America. He refused to spend a long layover in Nuremberg, owing to its identification with the Nazi Party. Instead, he arranged a trip to Bayreuth so that he and his family could fulfill a dream: to see the Festspielhaus and Wahnfried. The second anecdote comes from a Jewish woman from Berlin who remembers her “Wagnerian” conversion in 1936, at the age of ten, when she heard Furtwängler conduct the overture to Tannhäuser. After coming to America, she recalled, “When in 1944 I put on a recording of Wagner, another immigrant yelled at me ‘You have been Nazified!’ The next day I played Wagner’s music again, but as a Jew.”62

Bloch grew up in a non-Jewish neighborhood, but in a marginally observant home. His rediscovery of a Jewish national identity through Wagner is reminiscent of a far more significant journey taken nearly twenty years earlier by another highly acculturated Jew: Theodor Herzl (1860-1904).63 Within the spectrum of responses to Wagner among German-speaking Jews, none is more startling than Herzl’s enthusiasm for Wagner. As a student, Herzl witnessed the controversies of the 1870s and early 1880s. He reacted against Hermann Bahr’s anti-Semitic speech on behalf of one of the university’s Burschenschaften at the March 5, 1883, commemoration of Wagner’s death.64 Later, as a successful writer and editor in Vienna he experienced, like Adler, the centrality of anti-Semitism as a political and social force. Nonetheless, he fantasized in his early thirties that the solution might be a mass conversion of the Jews in Vienna’s cathedral, the Stephansdom.

Along with Adler, Mahler, and others of his generation, the young Herzl acquired a taste for the Wagnerian experience. The aspiring writer succumbed to Wagner’s success in drawing listeners into an intense, constructed world that seemed pregnant with meaning. The attachment endured beyond his youth. He confessed in his 1898 autobiographical fragment that during a crucial period of his life, while in Paris covering the Dreyfus trial, “I worked daily on [The Jewish State] until I was exhausted. My only recreation in the evening consisted of listening to Wagner’s music, particularly Tannhäuser, an opera I heard as often as it was playing. Only on those evenings when there was no opera did I sense doubt about the rightness of my thoughts.”65 Herzl’s 1895 diary recounts his return from a Tannhäuser performance, whereupon he sketched a vision of the future Jewish state where the masses would react, like the elite of the Paris Opera, “seated for hours, close together, motionless, uncomfortable,” for the sake of “imponderables—-just for sounds, for music and pictures!”66

The Wagnerian spectacle of music and drama and the community that formed around it within the theater helped inspire Herzl’s Zionism and his utopian vision of the future Jewish nation. The affinity with the Wagnerian ideal bolstered his self-confidence, his self-image as a leader capable of heroic sacrifice. Vivid and personalized fantasy, whether escapist or political, seems to have enveloped spectators of Herzl’s generation who became enamored of Wagner. Born 1860, the same year as Mahler, Herzl came of age in full recognition of the centrality of Wagner in European arts and culture, particularly in Germany. For his parents’ generation, who witnessed the rapid expansion of the composer’s popularity, Wagner represented radical aesthetic modernity. To Herzl’s generation, particularly to its Jews, Wagner was an overwhelmingly dominant cultural and political phenomenon that somehow had to be contended with.67

Herzl and his contemporaries recognized in Wagner a unique medium of communication that used word, sound, and sight—a musical drama—to reach a massive public for art and culture, well beyond the more limited public sphere that dominated high culture in the early and mid-nineteenth century. Before Wagner, a sustained tradition of connoisseurship had prevailed, that of the Liebhaber und Kenner, dating back to the era of Goethe and Beethoven. After 1815, aristocrats and an elite middle class allied to maintain an aristocratic cultural tradition as patrons, amateurs, and audience. Beethoven’s sponsors in the last years of his life reflected this combination, as did the support base for Vienna’s post-Napoleonic Society of the Friends of Music. This alliance was still intact when Brahms sought and got his first job in 1857 in Detmold. This exclusive, cultured class thought of music as a participatory art form, similar to but different from literature. Both music and literature required complex cognitive and physical attainments (reading, writing, singing, playing), and in both arenas amateurism was widespread as a mark of distinction.

From the 1830s on, the public for art and culture expanded and by 1860 had developed beyond the type of audience with which Mendelssohn and Schumann had made their reputations. Liszt and Paganini were the first to capture a new broad-based, middle-class public, using the theater of virtuosity and cult of personality as tools. But it was Wagner who reached the enlarged nineteenth-century public through radical innovations in the shape and character of the musical experience. He extended the theatricalization of music explicit in instrumental virtuosity and grand opera by placing drama, defined in terms of ordinary language narrative, at the core of his compositional criteria for melody and harmony. He crafted an expressive musical rhetoric and controlled musical time in ways that aligned the musical experience for the listener with expectations derived from new habits of reading associated with mid-nineteenth-century narrative in fiction and drama, notably the works of Balzac, Stendhal, and Sand, and later, Flaubert and Tolstoy. Their German counterparts were Wilhelm Raabe, Theodor Storm, Gottfried Keller, and Theodor Fontane.

The parallel between Wagner’s innovations for the opera stage and the nineteenth-century novel is instructive. In the epistolary novel and other prose fiction forms of the eighteenth century, events in the plot are not overtly reconciled with an awareness of the temporal presence of a narrator or with the reader’s self-conscious sense of his or her own time spent reading. Three active dimensions of time provide for a delimited and distanced illusion of realism. The essential artificiality of writing and narration as an object of contemplation is not camouflaged. Spitzer’s favorite novel, Tristram Shandy, is a famously extreme case. The nineteenth-century novel, however, sought to unify the three temporal elements into a single, continuous illusion of elapsed time in which both the reader and the narrator disappear under the weight of an illusory recalibration of real-time experience directed at the reader. When compared with eighteenth-century fiction, the nineteenth-century novel was far less philosophically self-conscious and made fewer demands on the reader: plot was manipulated to overwhelm any awareness of form, artifice, illusion, irony, and self-referential cues.

Like plot in the nineteenth-century novel, Wagner used music as the instrument of drama in direct opposition to the traditions of grand opera and so-called number opera. Wagner sought to cast a spell over his listeners that hid the artificiality of the stage and induced the listener to submit to a magical mythic realism.68 Even the role of music as defining the perception of time remained mysterious and overpowering, emanating continuously from the hidden orchestra at Bayreuth. Wagner wished to generate, partly through the extended duration of his works, an integrated psychological experience in which individuals lost self-awareness and were drawn into believing in the emotional and philosophical authenticity of extreme fantasy represented on the stage.69 Wagner collapsed the ironic distance between spectator and spectacle and thereby defined the terms of the modern theater in a manner that has remained valid for the commercial cinema of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Wagner’s aesthetic nemesis, Meyerbeer, on the other hand, refused to draw the audience into a coherent illusion of realism.70 He remained attached to an eighteenth-century construct of art as a mirror of sensibilities. Psychologically plausible and affecting moments of action were generated and then disrupted by Meyerbeer. The artificial scaffolding of spectacle remained fully visible and audible to the spectator. The listener was at once touched by the story, inspired by a nascent political message, enchanted by the music, yet reminded of a received tradition of opera and therefore thrilled at the novel theatrical devices and the star singers. Meyerbeer’s grandeur was evidently theatrical. Grand opera became a form in which irony and commentary accompanied representation, narration, and aesthetic pleasure. The listener remained conscious of his own time and place as well as his role as observer witnessing an intentionally inconsistent sequence of disparate theatrical segments. The scaffolding of the theater always remained visible, lending performers parallel identities as functional characters and real personalities.

Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929), the great German Jewish philosopher, argued in 1921 that the route that both literary and musical art took to enter the community in modernity required the transformation of the aesthetic into theater in the Wagnerian sense (even for poetry). For Rosenzweig, normative aesthetic values in works of art were accessible ultimately only to an elite. For art to reach a mass audience, these aesthetic values had to be transfigured into a seductive theatrical experience. In modernity, aesthetic purity had to be sacrificed on behalf of theatrical illusionism. All art needed to become Wagnerian: “The real drama is the drama of the book. For the aesthete it may seem a crime that it should become theatrical. Yet it is a crime for which Shakespeare is inexplicably forgiven, but Schiller and Wagner are much blamed, although surely the time will come (as it has already for Schiller) when Wagner will no longer be criticized for having written theatrically for the theater.” For Rosenzweig, dangerous as theatricalization might be to aesthetic value per se, Wagner’s work achieved legitimacy as “pure art.”

Wagner, like Shakespeare and Schiller, managed to preserve a valid aesthetic dimension despite his radical use of music as a theatrical framing device of communication with a large public. But the Wagnerian subordination of the purely aesthetic to the theatrical in modernity carried with it the danger of the corruption and debasement of the aesthetic experience of form and drama. In contrast to the demands Beethoven’s music asked of listeners, those who listened to Wagner no longer needed the capacity to recognize and follow aesthetic categories such as musical structure. Nonetheless, Rosenzweig defended Wagner’s art (just as Adler had) even if it “cannot wholly rid itself of the influence of the assembled masses.” In the theater, particularly in Wagner, an “ideal” world of the work fights for itself in the engagement with the “real” world of the assembled public.71

By the early 1920s, Rosenzweig’s assembled public—to which Herzl belonged and which he hoped, during the 1890s, would characterize the future Jewish state—represented not only a significant segment of the politically enfranchised literate population but also a considerably less musically trained public, despite the impressive spread of a passive piano-based species of musical literacy. Its “engagement,” as critics like Hanslick, Speidel, and Spitzer had argued half a century earlier, was no longer with musical culture per se (constituent elements of musical form in, for example, Bach, Mozart, or Schubert—Rosenzweig’s “pure art” and the “ideal” world of the work itself) but with the embrace of spectacle and narrative as persuasive, perhaps even escapist surrogates for the real.72

George Bernard Shaw identified the source of Wagner’s late nineteenth-century success with a markedly expanded audience in his 1898 The Perfect Wagnerite. He addressed “those modest citizens who may suppose themselves to be disqualified from enjoying The Ring by their technical ignorance of music. They may dismiss all such misgivings speedily and confidently. If the sound of music has any power to move them, they will find that Wagner exacts nothing further. There is not a single bar of ‘classical music’ in The Ring…. If Wagner were to turn aside from his straightforward dramatic purpose to propitiate the professors with correct exercises in sonata form, his music would be at once unintelligible to the unsophisticated spectator, upon whom the familiar and dreaded ‘classical’ sensation would descend like the influenza…. The unskilled, untaught musician may approach Wagner boldly; for there is no possibility of a misunderstanding between them. … It is the adept musician of the old school who has everything to unlearn.”73

Wagner reception in German-speaking Europe, particularly among Jews, was decidedly ambivalent about the radical accessibility of music as art that Shaw welcomed. Indeed, political and aesthetic considerations in rejecting or embracing Wagner’s “democratizing” innovations were inseparable at the fin de siècle. Wagner’s success in reaching a mass audience and generating a sense of collective euphoria through fantasy cloaked in the artifice of realism inspired Herzl with the possibility of generating a new political community. Socialist critic and Wagner admirer David Josef Bach (1874-1947), writing in Vienna’s Arbeiter Zeitung in 1913, argued reluctantly against maintaining Bayreuth’s hold over Parsifal precisely because of the imperative to realize Wagner’s accessibility to a wider audience. Yet his contemporary, friend, and fellow Jew Arnold Schoenberg was more skeptical about Wagner’s populist achievement.

Schoenberg sought to understand Wagner’s extraordinary capacity to reach the historically new and wider public in terms of compositional strategy. Wagner’s “evolution of harmony expanded into a revolution of form” and represented an “accommodation” to “popular demands.”74 The subordination of musical gestures to the task of expressing the so-called extramusical provided the public with a basis for intelligibility, a narrative equivalent located in an effective system of musical representation. As Schoenberg noted, he learned from Wagner three things: (1) the possibility of using themes as expressive, narrative vehicles; (2) the expansion of harmonic relationships; and (3) the use of motives and themes, primarily with repetition, so that in an enlarged harmonic landscape, dissonance could be incorporated and transcended.75

The endless melody, the repetition of motives, the shifting colors without harmonic closure through the extension of tonality, and the use of identifying signifiers attached to melodic fragments allowed Wagner to generate temporal continuity and to use music to frame a seamless story line with clarity that ensured easy comprehension and emotional engagement despite an enlarged harmonic palette. Novelty in harmonic logic and sonority became allied with populism, marginalizing the specialized learning, skills, and awareness of form required for the appreciation of music from the Classical period. Basic to Wagner’s intention was the rejection of the claim that music had an inherent logic separate from words and images. Accessibility through music depended on appropriating the linguistic and the visual into music. This integration was accomplished by Wagner’s virtuosity in using sound and color, rendering the façade and surface decoration of musical sound the overwhelming factor.76 By utilizing repetition to generate recognition of motives and musical rhetorical gestures, the link between musical events and ideas on the one hand, and narrative moments, on the other, was effectively communicated.77

The democratization of music, the extension of an elite eighteenth-century aristocratic tradition of music connoisseurship to the middle classes of the late nineteenth century, was viewed much more negatively by those for whom culture (Bildung) represented a prized possession whose value required that it be a hard-won mark of distinction. The accusation that Wagner represented a watering down of aesthetic standards became a clarion call among anti-Wagnerians like Spitzer and entered the nineteenth-century discourse of cultural decline that flourished throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Jews, for whom culture and learning had been successful meritocratic routes to integration since the late eighteenth century, worried about the loss of the exclusivity of their achievement of discernment as well as the cultural and political consequences of a debasement in taste and judgment.78

This discourse helped frame the fin-de-siècle debate over Wagner. Herzl, Bloch, and David Josef Bach admired Wagner’s capacity to enlarge the audience for culture and thereby place culture in the service of generating community as a species of democratization consistent, for example, with socialism and nationalism. But other Jewish intellectuals were skeptics who warned of the consequences.79 First among equals in this respect was Max Nordau (Simon Maximilian Suedfeld, 1849-1923), who would help found the World Zionist Organization and vigorously defend the importance of Offenbach, a cause he shared with one of his most vociferous critics, Karl Kraus.80

In his first book, The Conventional Lies of Our Civilization, published in 1883, Nordau called for a new politics of freedom, where heart and brain, the spiritual and the sensual, could find common ground in a new humanist credo. Wagnerian in its vision and scope, but philosophically inclined toward the Enlightenment, the book was banned in Nordau’s native Habsburg Empire. But Nordau turned away from this initial proto-Wagnerian impulse in his most famous work, Degeneration (1892), in which Wagner plays a crucial negative role alongside Ibsen and Nietzsche. The decorative, seductive surface allure of Wagner, the musical qualities Schoenberg identified as the substance of the Wagnerian narrative and which had contributed to Wagner’s wide popularity, led to the danger of widespread moral, civic, and physical deterioration. Wagner was guilty of Nordau’s pet sins: egomania and the manipulation of the mystic and the symbolic. Wagner was dangerous because his obscurantism was popular and had so many imitators.

In the fin-de-siècle debate, as Nordau’s 1892 attack on Wagner suggests, not all Wagnerians were nationalists, and not all anti-Wagnerians were dreamers on behalf of universalist utopias. Nordau never lost his own intuitive penchant for Wagnerian grandiosity in the language and scale of his ideas. In 1897, the anti-Wagnerian Nordau joined in earnest the Wagnerian Herzl and the Zionist movement.

Those opposed to Wagner could also be radical cultural nationalists. Within his vigorous and harshly chauvinist argument on behalf of German music, the virulent cultural nationalist Heinrich Schenker (1867-1935) accused Wagner of having been unable to compose in the tradition of Beethoven. Schenker took his cue from Spitzer but extended Spitzer’s argument about Wagnerian language into an extreme critique of Wagner’s compositional practice. Wagner had devised unacceptable shortcuts in the use of musical materials through the creation of the “so-called music drama.” His innovations may have been idiosyncratic, but they were crude simplifications of a great artistic tradition. Wagner could not stand the “fiendishly difficult” task of real composing. If composers and listeners enamored of Wagner, “roll about… [in] something that can no longer be called the basic material of the musical art,” argued Schenker, “then, as I said, Richard Wagner alone bears the blame for having demobilized, as it were, their musical nerves.”81

Schenker remained an observant Jew who was active in Vienna’s Jewish community.82 He was a lifelong defender of Brahms as the last great master. The procedures represented by the apex of the Classical tradition, in which music was considered autonomous and possessed of its own self-referential logic, divorced from visual associations and expressive linguistic meanings, were normative. This meant that Wagner’s musical practice embodied a corrupt cultural representation of the German, an intolerable alternative construct of Germanness. Like Spitzer and Hanslick before him, Schenker’s admiring vision of German superiority harked back to an earlier era, that of Goethe and Beethoven.

Schenker’s views were not unique. Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931), a non-observant Viennese Jew, also distanced himself from Wagner and Wagnerism. As Marc Weiner has argued, Schnitzler views Wagner critically in his great 1908 novel Der Weg ins Freie, both for Wagner’s role in politics (particularly anti-Semitism) and the subordination of musical aesthetics to the demands of theater, narrative, and ideology. Schnitzler agreed that Wagner called for a new kind of listening, a debased perception of the musical experience that inspired either a senseless modernism or a kitsch sentimentalism. The one character who hears music properly, in the sense Schenker defined it (better than the contemporary mass audience), is not the novel’s aristocratic protagonist, Georg von Wergethin, but his friend, a Jew, Leo Galowski.83

In 1900, Max Graf (1873-1958), a twenty-six-year-old Jewish critic, dedicated a book to Mahler titled Wagner Probleme. Graf took a psychological route in his argument against Wagner.84 He used Wagner’s flawed personality to generate an aesthetic critique in which Wagner was invidiously compared with Beethoven. Despite his greatness, Wagner fell short. He lacked character, the sustained aesthetic and creative energy, and the consistency characteristic of Beethoven, Goethe, and, of all people, Bismarck. Graf rejected the cultural and racial idealization of the German encouraged by Wagner in favor of the more limited political definition represented by Bismarck’s Prussian-based achievement.

Wagner’s nature was too “elemental,” Graf wrote. His art was shaped by radical extremes and lacked a firm center and foundation. In Wagner there was a consistent cry “for redemption” as opposed to a “blessing of life,” the proper purpose of art.85 Wagner’s inner unconscious life was one of contradictory impulses characteristic of an “unstable conflicted” personality.86 Graf asked whether a new generation wishing to embrace beauty and positive energy should take as a model Wagner’s “affecting cry of need,” mirroring a “bewildered and longing soul” in search of death and redemption. Would not Beethoven, who, according to Graf, ended his life with “a hymn to joy,” be more appropriate? Graf concluded, “Is the art of Richard Wagner more than the work of an artistic genius, is it really the work of a new culture? Is it more than the work of a representative of modern society and culture who suffered from it and remained unfulfilled and still longing, and who with great effort transcended his historical context just enough to gather around him other longing and unfulfilled spirits? Does it do more than lead us out from modern civilization; does it really have enough power to gather new forces and unite them?”87 Graf’s answer was clearly no, echoing the responses of Schoenberg and Schenker.

These sentiments led to a search for new non-Wagnerian approaches to musical form and content. Schenker and Schoenberg may have agreed on the character of Wagner’s revolution in musical composition. Since they diverged on how deleterious it was, they developed different definitions about what a restoration of pre-Wagnerian musical standards would sound like. Schoenberg (Graf’s exact contemporary and a figure Graf championed) saw the next step as a progressive historical extension, building on Wagner’s achievement through the work of a key intermediary figure, Mahler. Schenker’s views were more reactionary, restorative, and conservative. He rejected Mahler, whose interpretations of Beethoven and compositions he regarded as too influenced by Wagner’s superimposition of narrative meaning onto music and Wagner’s emphasis on sonorities and melodic contours. Wagner’s anti-Semitism was not an overt cause for the skepticism of Schenker and Graf. The same can be said for Schoenberg, who never doubted Wagner’s achievement as a composer. Rather, he took a line more akin to that of Adler, and placed Wagner alongside Beethoven and Brahms as representative of a musical tradition that demanded a novel response by a new generation. For all three figures one can speculate that their identity as Jews played a role, but in an indirect manner. All three figures sought to reassert or reclaim an aesthetic tradition that predated the advent of modern nationalist and racialist politics.

In 1937 Schoenberg recalled the genesis of his 1906 Kammersymphonie, op. 9. He thought he had found an alternative, “a way … out of the perplexities in which we young composers had been involved through the harmonic, formal, orchestral and emotional innovations of Richard Wagner. I believed I had found ways of building and carrying out understandable, characteristic, original and expressive themes and melodies, in spite of the enriched harmony that we had inherited from Wagner.”88 The key idea was to sustain comprehensibility but to reject repetition and scale, thereby returning in a starkly contemporary manner to a mode of composition more characteristic of Beethoven and Brahms. Indeed Brahms, Wagner’s antipode, became for the fin-de-siècle anti-Wagnerians not only emblematic of an older refined culture in opposition to Wagnerian extravagance and vulgarity, but also the source of a new, progressive modernism.

There was little doubt that Wagner had developed in music a compelling equivalent of the nineteenth-century novel in scope, length, and depth, constructed by a musical prose that exhilarated and captivated the audience in a nearly hypnotic and dangerous manner.89 The nearly irrational allure of Wagner’s music to the German public during Gründerzeit, from the 1870s until the outbreak of World War I, confirmed to both sides of the fin-de-siècle debate the extent to which Wagner had realized Schopenhauer’s view of the Will and music’s unique role as the direct expression and not mere representation of the Will—despite the philosopher’s own misgivings about Wagner. But this extreme popularity also generated misgivings, fear, and caution regarding Wagner’s influence, particularly among Jews.

In 1913, the fin-de-siècle polemical debate reached an apogee, including an aggressive Wagnerian retort to the composer’s new critics. German-speaking Jews were prominent on both sides. Emil Ludwig, the wildly successful popular writer, gave his 1913 anti-Wagner book the title Wagner oder die Entzauberten (Wagner, or the disenchanted), using a word that suggested the necessity of reversing the effects of Wagner’s magic. Ludwig sought to highlight the contrast between reason and the irrationality and illusion-ism generated by the embrace of Wagner.90 For Ludwig, a spell had to be broken in politics and culture if Adler’s “monstrous conclusions” were to be avoided. Only Tristan eluded Ludwig’s criticism. The danger to culture rested not in the “people” but in the “spiritual bourgeoisie” who had been seduced by Wagner, a stratum between the connoisseurs and the modern masses. Ludwig contested the 1871 claims of Cornelius. Wagner had not reached Germany’s “people.” He merely persuaded an expanded but still elite taste-making “public.” Ludwig rendered Wagner the object of the very criticism that the Master himself had directed at a Jewish elite in 1869.91

Following Nietzsche’s anti-Wagnerian writings, Ludwig accused Wagner of being merely an “actor” who succeeded only with a like-minded public enamored of spectacle. To have persuaded the “Germans” as a whole nation, Wagner needed to have been an authentic poet, dramatist, or a musician, a proponent of absolute music.” Ludwig’s position resembled Graf’s and Schoenberg’s. Wagner’s failure created an opportunity for contemporary culture. Ludwig’s prescription came closer to Schenker’s.92 The solution lay in a return to Mozart: “Mozart will ‘redeem’ us who are young from Wagner,” Ludwig wrote, thereby relegating Wagner to a historical monstrosity akin to Bernini. The task for modernity was to restore clarity and lightness to art and culture.93

Two critics, both Jews, challenged Ludwig: Paul Stefan and Kurt Singer.94 Stefan’s 1914 Die Feindschaft gegen Wagner argued directly not only against Ludwig but the entire history of anti-Wagnerian criticism, from that of Wagner’s early career through to Nietzsche and Ludwig. Stefan, following Adler, rejected the relevance of any criticism of Wagner’s personality or writings. However, he took a more classic Wagnerian line by blaming mere journalists for defaming the Master. Stefan, who ridiculed Ludwig’s appeal to Mozart, turned the tables on the critics. At the center of the younger generation’s doubts about Wagner was the composer’s courageous unwillingness to hide behind anachronistic and normative notions of artistic beauty and health (absolute music) in the face of the complexity and contradictions of modernity. Wagner’s inspiration stemmed from his recognition of the unique character of modernity. Modernity, for Stefan, was not comforting, logical, or beautiful.95 Hence he celebrated Mahler as a true contemporary voice, one clearly indebted to Wagner.

Singer took a similar pro-Wagner line in a set of essays from 1913, Richard Wagner: Blätter zur Erkenntnis seiner Kunst und seine Werke. Singer weighed in on the Parsifal controversy, for which he suggested a compromise that would cede control of performance standards to Bayreuth but open the possibility for performances elsewhere. Singer felt compelled to use his “expertise, experience and good will” to reassert the “ethical, artistic and poetic foundation of the Wagnerian work of art.” The “endless feeling” that emerges from late Beethoven is the same as that which Parsifal generates: a humbling sense of insignificance as if one were near the presence of God. For Singer, Wagner’s works had the power to form a community out of the aggregate of alienated individuals in modern society by inducing a shared sense of recalibrated time as well as a sense of fantasy. They did this by using an extension of sound that was simple to follow precisely because musical elements were linked to a non-musical narrative and symbolism. The parallelism between music and ideas was a virtue. The music and its many moods could be followed easily by listeners without requiring them to follow musical logic per se (e.g., the transformation of themes). Singer, like his contemporary Paul Bekker, understood Beethoven, particularly late Beethoven, in this distinctly Wagnerian manner, as music that argued through instrumental music ideas and sensibilities, and that these rendered possible the formation of communities of shared sentiment.96

What emerges from Singer’s defense of Wagner is a common thread linking turn-of-the-century Jewish Wagnerians with Jewish critics of Wagner. Wagner’s success in captivating the public and its imagination impressed both sides, primarily with regard to the importance of building communities in modernity—both spiritual and political ones. The fear of fragmentation and alienation that accompanied the nineteenth-century urbanization of Europe and its industrialization was that human beings would find themselves isolated, exploited, and without a spiritual center, particularly in a world dominated by a mix of rationalism, competition, and skepticism. The acculturated Jew, a new arrival as a social, economic, and political actor in public life, became at one and the same time the emblem of the perils of contemporary existence and identified as a primary cause of modernity’s ills. It is not surprising, then, that a nearly romantic attraction to the idea of community was a common element in the Jewish response to Wagner, both pro and contra. The Jew was, after all, the ultimate pariah who sought entrance as an outsider into a community imagined as authentic. Insofar as culture was a route to that membership, music, whose life took place both in private and public spaces, became a central arena of Jewish ambition. The attraction to musical culture in the fin de siècle was precisely its post-Wagnerian prestige as a powerful element of the formation of community, even the new national community of Jews envisioned by Zionism.

Singer predicted that in a hundred years Wagner would be regarded alongside Leonardo, Raphael, Bach, Beethoven, Goethe, and Schiller as the source of a “healthy culture of the spirit.”97 The figure of Siegfried represented the integrity of the artistic idea, the breaking of the limits of mortality, the spirit of the divine, and the mirror of the essentially human. Singer was an unapologetic enthusiast of the ethical value of Wagner for a new generation. Wagner’s positive influence over the modern mass public would become increasingly visible with the passage of time. Singer hoped to encourage the direct study of Wagner’s works so that his greatness and centrality to the formation of cultural values could be appreciated.98

Perhaps the most eloquent account of the issues at stake in the fin-de-siècle debate over Wagner’s potential relevance to a new generation and a new era of artists and listeners was that of Egon Friedell. The son of a Jewish manufacturer, Friedell (1878-1939), born Friedmann, worked as cabaret artist, actor, and writer.99 As a student in the late 1890s, he, like Schoenberg, converted to Lutheranism. He was best known as the director of the theater cabaret Die Fledermaus (for which the designer Josef Hoffmann designed furniture). Yet Friedell was admired as both a satirical and serious writer on history and culture, and as a translator.

In the late 1920s Friedell began his most enduring work, a three-part Cultural History of Modernity completed in 1931, in which he devotes space to Wagner. Having witnessed the fin-de-siècle controversies, he revealed a distanced skepticism toward Wagner and a resistance to his charms characteristic of his generation, but without losing sight of Wagner’s genius. Following Adler and Graf, Friedell viewed Wagner as no longer contemporary or relevant. He should be understood primarily (as Ludwig did) as a “baroque” artist from the past, a master of effects (here Friedell followed Nietzsche), and therefore principally a theatrical genius. In Wagner’s art one could actually witness the “fall of a bourgeois worldview” precisely on account of Wagner’s brilliant manipulation of bourgeois taste. Wagner, concluded Friedell, “suggests the recollection of [baroque] culture not only through the pomp and aplomb of his prolix persuasions and his yen for the mystical… but also by his sensual will toward the spiritual … his cramped and yet delightful artificiality, but most of all through his refined mixture of eroticism and asceticism, of the ardor for love with the yearning for death. His is a sultry metaphysics, that in a particular way … is anti-Christian and frivolous…. The secret of life is revealed as biological, in a word: understood as Darwinian…. The ‘music drama’ is the spellbinding funeral march, the extravagant burial service at the grave of the nineteenth century, and of modernity in general.”100 Friedell’s observation coincides with the critique by many of his contemporaries of the eclectic historicist character of nineteenth-century art and architecture, perhaps best exemplified by the elaborate and decorative costumed parade involving 14,000 participants engineered and organized in 1879 by the Viennese artist Hans Makart (Wagner’s favorite painter) to celebrate the silver wedding anniversary of the Emperor Franz Joseph II.

Friedell understood Wagner’s achievement, albeit more charitably, in much the same way Spitzer and Ludwig had. Writing after the catastrophe of World War I, Friedell concluded that Wagner created a new audience and thereby broadened an ultimately eclectic and insufficient set of values characteristic of pre-World War I bourgeois culture. That culture’s pomposity revealed an absence of humor, self-critical satire, simplicity, and clarity, qualities the contemporary world required from music and literature. Wagner represented a dead end, a mannerism from the past. An ambivalent mix of regret, pessimism, and hope concerning the role of art and culture characterized Friedell’s magnum opus. He committed suicide on March 16, 1938, shortly after the Anschluss, jumping from his window to his death while the SS below were arriving to arrest him.

Paul Stefan’s pro-Wagner tract cited slyly, in passing, perhaps the most widely read fin-de-siècle Jewish voice on the subject of Wagner, one for whom the Jewish question was central: the elusive and influential Otto Weininger (1880-1903). Weininger not only built an original theory on the basis of Wagner’s anti-Semitic arguments, he also internalized them. He committed suicide in 1903, at the age of twenty-three.101

Weininger used Wagner’s writings and works to generate a theory of sexuality in which the Jew was the feminine and the Aryan the masculine. Weininger’s 1903 Sex and Character, reprinted many times after his death, had a profound impact on the likes of Ludwig Wittgenstein, Schoenberg, Freud, and Karl Kraus. Weininger viewed the world through the prism of fertile dualities: male versus female, character versus form, talent versus genius, erotic versus aesthetic. For him, Wagner represented the highest aesthetic achievement in history. Parsifal was the greatest of his works (and Kundry was perhaps the most perfect representation of a woman in art).102 Weininger concluded, “What I seriously wish to try to show—not because everything that Wagner created seems extraordinary—is that the Wagnerian invention [Dichtung], on account of the profundity of its conception, is the greatest invention in the world.”103 Stefan had cited Weininger to counter facile attempts to dismiss Wagner purely on account of his anti-Semitism. Stefan suggested quite the opposite. Citing Weininger, Stefan hinted that Wagner’s arguments in “Judaism in Music” were creditable and worthy of careful consideration.

Weininger’s most powerful duality pitted the Jew against the Aryan, whose modern form was the Aryan Christian. Weininger read Wagner closely. He was inspired by the way in which Wagner interpreted Jewish assimilation into non-Jewish culture. Wagner pilloried the Jewish capacity for imitation and mimicry, the Jewish talent for calculation, abstraction and business, and the Jewish skill in manipulating systems, notably commerce (capitalism) and the press. The Jew attacked most vigorously by Wagner was not the ancient Jew, represented in modernity by observant pious adherents to religious traditions and who lived in ghettos, but the modernizing Jew, the outwardly successful and assimilated urban Jew: the Mendelssohns, the Meyerbeers, the journalists and critics, the businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and scientists.