The flautist, music theorist, composer, and writer Johann Christian Lobe (1797-1881) embarked on a career in music criticism as early as 1826 as co-editor of the Musikalische Eilpost, and would work as correspondent, columnist, reviewer, and independent writer for a host of the most respected music journals and newspapers in Germany before editing the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung in its final years (1846-48) and the music section from the Leipzig Illustrirte Zeitung (1861-63). By the mid-1840s, needless to say, he was intimately enmeshed in the debates about the purpose of music criticism, as well as acting as one of the profession’s central voices.

The fourteen Letters to a Young Composer About Wagner were published between 1854 and 1855 as part of Lobe’s self-authored music journal, the Fliegende Blätter für Musik: Wahrheit über Tonkunst und Tonkünstler (Loose leaves on music: Truth about musical art and musical artists), 1853-57.1 This consisted of quarterly installments of about sixty pages containing essays and letters as well as smaller entries of anecdotal significance; it was written entirely in the first person—acknowledging the author’s subjectivity—and had the purpose of making music accessible to as wide an audience as possible, though aside from connecting with the midcentury Bildungsbürgertum (an embryonic form of the bourgeoisie proper), the journal likely had very limited effect on the business class within the middle strata of society, and probably had no impact whatsoever on the rural population, which by 1848—following the steady growth of the small peasantry and a landless “underclass”—still constituted three-quarters of the people within the German states.2 Thus, Lobe’s altruistic outreach effectively applied to non-music specialists within a small, educated class. On the other hand, J. S. Dwight estimated in 1855 that as many as one in two people between the ages of ten and forty in Germany “has undergone some sort of musical training,” and “at least” nine out of ten take “some interest” in musical matters.3 The relatively small circulation of the major music journals—projected at under three thousand subscribers by Dwight—was a result of their impractical content, he surmised, which disregarded what the public wanted. Lobe’s intention, at least, was thus to reach this wider, musically inclined demographic.

With this in mind, Lobe first expressed a sympathetic view of Wagner’s music in 1850 when he favorably reviewed Liszt’s Weimar premiere of Lohengrin in Heinrich Laube’s Signale für die musikalische Welt, eliciting an uncharacteristically friendly response from Wagner.4 In 1853, Lobe further defended Lohengrin and Opera and Drama against chronologically confused criticism from Julius Schaeffer, a Wagner supporter whose serialized, analytically dense monograph measures the essay against the opera with unwitting sophistry.5 A year earlier, Lobe had half-cynically characterized the relationship of Wagner’s operas to Opera and Drama as that between heavily laden sailing ships stuck at port (in windless weather) and a bellowing breeze; Wagner’s essay whipped up such a “wind” that his fleet of dramatic works now “float with full sail on the sea of his fame.”6 Yet on the whole, Lobe disapproved of Wagner’s polemical writing about music, assuming an aesthetic stance fundamentally opposed to increasingly jaded notions of “progress,” a common cry he likened dismissively to the squawking of parrots.7 Indeed, it was even argued at the time that the Fliegende Blätter were conceived entirely “in opposition to the extravagances of [Franz Brendel’s] Wagner organ,” the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.8 Although Lobe’s biting satire of 1857, “A New Prophet of the Future,” is not a direct attack on Liszt, Wagner, or Berlioz, it nevertheless takes aim at those composers whom he felt wrote incomprehensible music under the protective banner of Zukunftsmusik.9 The main reason for the poor quality (and rapid disappearance) of many newly composed German operas, he argued in 1852, was that composers forgot to write “for their contemporaries,” and instead sought out their fame by anticipating the future.10

Accordingly, Lobe admires conservative elements in Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, which he analyzes in terms of symmetrical, periodic melody, and formal structure. In the second letter he even rewrites Wagner’s theory of a synthesis of the arts to justify it, in organicist terms, as the natural corollary of working from a single, poetic idea (Idee). Parroting “progress” was leading inexperienced composers astray, he feared. A response to this situation is Lobe’s detailed analysis of the Tannhäuser overture, prompted specifically by Wagner’s poetic program written for concerts in Zurich (1853), which Lobe systematically picks apart in his fourth letter.11 Foreshadowing the corrective approach to Wagner, Lobe had analyzed the “progress” that Niels Wilhelm Gade had made in his celebrated third symphony (1847), and deduced that Gade had not in fact progressed beyond Beethoven. In that earlier essay, Lobe concluded that trends in criticism toward the “future” and “progress” were tempting young composers to innovate at the expense of appropriate study of older masters.12 Hence, the Wagner letters are addressed specifically to such young composers.

Untangling the discourse of critics and mediating partisan views is Lobe’s initial concern. He opens his letters by contrasting newspaper snippets that praise and censure Wagner’s Romantic operas with equal ferocity. Writers are too one-sided, he begins diplomatically. The reader should look first at what Wagner has achieved as a composer, not what has been written about him (or what he himself has written). Practical considerations—such as the impossibility for smaller theaters to perform Wagner’s operas, and the corresponding difficulty for people to actually hear and see them—also influence Lobe’s didactic tone. The striking means by which he shepherds his readers through Wagner’s unfamiliar scores is extensive musical illustration (including harmonic reduction), with all the “see for yourself,” hands-aloft innocence such an approach projects. The tacit assumption is that musical notation that represents or in-scribes the works themselves (however philosophically problematic this equation may be) will trump the polemically biased and personally motivated arguments that describe or de-cipher the operas’ content into a critical muddle. In Franz Liszt’s discussions of Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, the musical illustrations are offered as a means of sharing his listening experience with the reader. In Lobe’s paradoxical view, on the other hand, music is posited as visually self-evident; against a wash of dirty phrases in the Wagner discourse, the notation functions as a cleansing agent, apparently offering a way out of the vortex of disagreements. Throughout his career, Lobe’s view was that aesthetic criteria were not determined by philosophical systems, but by the musical works “themselves.” As late as 1869, he continued to be respected for the salutary, “refreshing” impact his approach could offer.13

The Fliegende Blätter exemplify this perspective and enjoyed international circulation, as a New York reviewer put it, “in consequence of the practical knowledge and experience in musical matters exhibited in them.”14 Since a variety of serialized articles and letters extended through the various journal issues, Lobe anticipated that his readership would follow not only one series, but read his other articles as well, and he occasionally cross-references his work with this in mind. The Fliegende Blätter were even considered “a continuation of [Lobe’s Musical] Letters,”15 that is, of his Musikalischen Briefe—published in 1852 under the pseudonym “Briefe eines Wohlbekannten”—which also bore the subtitle: “Truth About Music and Musicians.”

A particularly relevant series contemporary with and reinforcing the aesthetic stance of the Wagner letters was Lobe’s “Aesthetische Briefe” (Aesthetic letters), in which he isolates music-analytical parameters for interrogation, including rhythm, harmony, melody, tone, dynamics, as well as modulation, modality, and key. The background for Lobe’s skepticism about Wagner’s rejection of most prior music, indeed about Wagner’s aesthetic “system” tout court, is further grounded, for instance, in his very first “Aesthetic Letter”:

There is no musical work that will give pleasure (or appear beautiful) to all men in every era. For that reason there can be no single, eternally valid aesthetics … [He] who gathers and assembles the rules according to which … [paradigmatic] works are created will at any rate provide the best musical aesthetic relative to his own time.16

Since Tannhäuser is predominantly the lens through which Lobe focuses his critique of Wagner, the letters selected for translation here focus exclusively on Lobe’s analysis of the Tannhäuser overture to aid comparison with Liszt’s text about the same, also included in the present volume.

JOHANN CHRISTIAN LOBE

Letters to a Young Composer About Wagner

From Fliegende Blätter für Musik: Wahrheit über Tonkunst und Tonkünstler

Leipzig, 1854–55

A few think in this way, and many appear to want to do so; they shout and set the tone; the great mass remains silent and behaves indifferently, and sometimes agrees and sometimes disagrees. (Lessing)17

You have read it often enough and can still read it daily (for one side never tires of repeating things): a principal merit of Wagner is that he demands in his writings—and strives to apply in his works—an entirely new, indeed the only right-minded artistic direction in both operatic poetry and composition.

With this, the art lover is quite naturally directed toward the main vantage point from which he should observe, examine, and judge Wagner’s music. This cannot happen, however, should one want to reach no more than a fairly plausible conclusion, with general propositions and gushing phrases; rather one must turn to the facts and ask oneself whether what is attributed to them is really there to be perceived.

Tannhäuser and Lohengrin constitute such facts.

Admittedly, Wagner does not yet want to acknowledge either work as a completed expression of his new system, but allows them to be performed where one wants to perform them. His friends raise them as felicitous proof of the new direction above all else that has been achieved before him by musical minds18 of greatest genius in this field, and we cannot know what more he will achieve in them. We must therefore adhere to that which we have before us.

The first question for every artwork one wants to treat fairly must be: What did the artist intend with it? The second: Is the intention artistically reasonable? The third: Did he achieve this entirely, or only partially, or not at all?

Nobody will have any objections to these questions. I did not invent them, they lie in the nature of things, and have long been recognized as safe guiding criteria. Let us attempt to answer them in turn with good intentions and according to our best knowledge and conscience.

Wagner rejects all absolute music in his writings, i.e., all music that aims to describe something definite without recourse to words, as something for which its indefinite means are insufficient.19 To begin with, this is nothing new, but rather a time-honored view. Wagner’s overtures and introductions, his marches, preludes, interludes, and postludes in his operas prove that he does not count as absolute music that music whose content is to be intimated through a program, or is to be inferred from a given plot.

The Adagio from the Don Giovanni overture anticipates the entrance of the petrified guest in the last finale; the introduction to Lohengrin anticipates Lohengrin’s entrance in the opera. The overture to Freischütz prefigures a series of moments from the plot, the overture to Tannhäuser does the same.

Let us take a close look specifically at the latter work, and direct our first question to it: what did the artist intend with it? The answer can only be: absolutely nothing different from what Weigel before him intended in his overture to Schweizerfamilie, or Weber in his overtures to Freischütz, Oberen, to Euryanthe, or Beethoven in his three overtures to Leonore, etc. The second question therefore takes care of itself. What all of these masters accomplished, including Wagner, will probably be artistically reasonable.

The question remains for Wagner: did he achieve his intentions entirely, or only partially, or not at all?

But this question would be blasphemous in the eyes of the converted, for Wagner’s principal merit is of course the new direction that so markedly surpasses all precursors.

Thus we know to look for it in this overture nowhere more than in an increasingly powerful artistic treatment. Wagner will have expected his Tannhäuser overture to express something more specific, and he will have accomplished this in a far more excellent, truer, more apparent and more influential way than was ever possible for an earlier master.

This, my young friend, is what I want to examine as uninhibitedly and as precisely as possible after having become acquainted with the music through multiple listenings, score in hand.

That our composer was absolutely conscious of what he wanted to describe in the overture lies beyond all doubt.

Through his accompanying written program Wagner has documented irrefutably that he meant to express more in this overture than any other master before him, the most daring and genial not excepted.20

I want to set out for you the view on this of an unknown writer from the Augsburg Allgemeine Zeitung who discusses the performance of the overture in Vienna, first because of the apposite expression of some thoughts, and further to refute some matters in favor of Wagner, since it seems to be his tragic fate that his judges are unable to keep in balance either the “for” or “against.”

The anonymous author writes:

Wagner proved that he still bears a secret love in his heart for these “dated viewpoints,” for he still wrote a clarifying program for the Tannhäuser overture at the last music festival in Zürich.21 This program—it lies before us—turned out strangely enough. We should really see with the ears, also smell at times, e.g., a “slim, youthful man”—Tannhäuser—“rosy mists”—“delightful scents,” an “unspeakably enticing female form”—Frau Venus and such. In the end this even amounts to the musical solution of a philosophical problem: “the two sundered elements of spirit and senses, God and Nature, embrace one another in the sacred unifying kiss of love.” The essence of this music, even a naïve reader must admit, lies in not being music; it is only fed to the imagination as a means of generating figures, in the process of which one never enjoys the freedom to imagine what one wants. The glorified nonsense that surrounds the Wagnerian interpretation of his overture fades somewhat, however, if we remember that this piece of music is put together from separate components which, individually, have their attendant meaning for the corresponding places in the opera. The overture, precisely because it is no introduction but a compressed summary of the whole, requires an acquaintance with the complete opera to be understood.

The final verdict of this Viennese judge of art reads: “It is a sorry effort pieced together without inner development, without organic execution that—one understands not why—breaks off suddenly!”

You know Wagner’s complete program from an earlier issue of the Fliegende Blätter für Musik where I compared it with one by Berlioz to show that Wagner criticizes others in the harshest terms for the very things he allows himself to a far more exaggerated degree.22 According to him, Berlioz demands that music express what music absolutely can never express, whereas Wagner, as you have just read, requires his music to paint.

Now this would certainly be a new direction of intent, but since it demands something that is quite simply impossible, it is an absolutely false one.

In this peculiar case, to avoid exploiting with hostile spirit the strengths of Wagner the composer against the weakness of Wagner the writer of programs, one comes to defend the weakness of the former to the detriment of the latter.

His intention is not nearly so bad in this overture as it might seem in light of his program. The music is comprised of discrete sections from the opera, and in the opera Wagner, of all composers, surely wants nothing more than that which all good masters have wanted and done before him. He expresses a character’s feelings and, in doing so, symbolizes with his tones as far as is possible and productive the inner and outer ideas that those feelings induce and provoke. In the Pilgrim’s Chorus he paints the sentiment of the penitents; of course, it does not enter his mind additionally to depict their figures, physiognomies, clothing, etc. Tannhäuser’s song in praise of Venus expresses his drunken love for her. Wagner would have refrained from painting Tannhäuser’s slender figure—even if tones were capable of depicting a person externally—because in the different possible Tannhäusers on stage he could not have counted on having only slender tenors, and could have run the risk of being proven a liar by a theatrical squirt. A rosy scent settling over the stage is not merely smelled, but also seen, and a composer can try hard to symbolize secondarily the appearance of color in nature, and has famously done so often enough, with and without success. Should the tone poet tasked with depicting a scene that takes place in darkest night not be able and allowed to awaken the idea of darkness in the listener’s imagination with a dark instrumental color? Has Haydn not already in his famous passage managed to sensualize the entry of light through a tone picture, so that one believes one is really seeing light with one’s ears (to use the Viennese expression)?23

So, to defend Wagner against himself concerning the relationship of his program to his music goes like this: if, like Berlioz, he had simply cared to write: Procession of Pilgrims; —magical apparitions at nightfall, lustful cries of joy; Tannhäuser’s proudly celebratory love song; uniting of the Pilgrims’ song with the cheers about the release from the Venusberg, etc. —well, in that case nobody—the Viennese critic included—would have had any objections, and all would have considered the matter quite natural and long customary.

Admittedly, Wagner and his friends want to talk us into believing that he does nothing like other artists, rather he does everything entirely differently, entirely new and more beautiful, deeper, more sublime, more art-worthy.

And here, my young friend, I come to the most dangerous point in the literary wheelings and dealings of Wagner and his largely or seemingly unconditional admirers. With unmistakable art and political savvy, Wagner and his acolytes use the same methods that have given rise to and continue to preserve the immense power of hierarchy: the power of resolutely persuasive, holy, awe-inspiring language, in the garb of infallibility, now apparently humble, now striking down with excommunication and sentence of hell, threatening and thundering against non-believers, even slight doubters. If you read papal allocutions, archiepiscopal pastoral letters, and compare these with most of Wagner’s writings and those of his priests, it will immediately become clear to you what I mean.

This manner of representation with its purpose of letting a higher glory shine around Wagner’s head than that allotted any earlier master (in the eyes of the great, undiscriminating mass) dictated through the phrases of his “program” by the very quill of the composer, can well be called, as has the Viennese critic, “glorified nonsense.”

We then read: “This is the seductive magic of the ‘Venusberg,’ which can be heard at nighttime by those in whose breast there burns a brazen, sensual longing.”

One strains the ear in vain, however, to hear this “seductive magic” during performances of the work. For me at least, with the best intention and passable aural skills, it was not possible to hear anything of the sort.

One reads: “A slim, youthful man appears, drawn by these seductive apparitions: this is Tannhäuser, the singer of love.”

This is pure swaggering, intended for all-believing, unmusical readers. No composer in the world can depict such things with tones. Only the poet can awaken them in the imagination with words, only the painter and sculptor can bring them before our eyes’ sensory impression through colors and stone.

“He sounds his proud, triumphant love song as a kind of joyful challenge to that sensual magic, bidding it approach him.”

The tone poet can express the first part of this instruction, and he can do it in such a way that the mind is gratified by the fitting veracity of tones, the imagination by the novelty of the figures, and the ear by the magical sonority of the tones.

Just how far the music for this passage fulfills all of the expectations aroused by Wagner the author, thereby hugely outstripping all earlier composers of genius, I will leave to your own judgment in a later letter where I provide musical notation for your eyes and inner hearing.

“He is answered with wild cries.”

Good. The composer may want to depict that. He does not merely sensualize wild rejoicing for us, but also lets us hear comfortable, pleasing music alongside. The description of what one ought to hear reads as follows:

“The rosy mists close about him more densely, delightful scents surround him and intoxicate his senses. In the seductive twilight atmosphere there materializes before his wonder-struck gaze an unspeakably enticing female form”—and a further number of similar promises (which you yourself may read in the program booklet) belong to such exuberances, which the poet can stimulate with words as a vague play of premonition in the imagination of the reader, but which the composer—no more than Schiller’s “Power of Song” with its audible music can bring to satisfactory, confirmative, and effective expression. In his work, Wagner can never have intended for music to express such things as are absolutely inaccessible to it; he can have intended this all the less, since he reproaches Beethoven and, to a greater extent, Berlioz for precisely this. Nor can Wagner, after his work, have believed that these things had been instinctively created within it through his own genius and without conscious intention;24 he now recognizes this plainly and thus wants to make it clear to the public after the fact, through the program. No, neither the one nor the other dictated those deceptive phrases in his program. It was, rather, either conscious intention or at least instinctive feeling, the deep poetry of his soul, the most ardent and highest artistic intentions, and the power and truth of musical expression (far surpassing all before him) which he wants to possess or perhaps imagines he does possess and which he at least struggles to awaken and fasten upon the credulous world with a fervent longing, energy, and stamina that cannot be praised enough.

Does that sound rather hostile and far from impartial? Patience. In case you should think so now, you will change your views in the next installment. I want to attribute the exaggerated excellence one imputes to him to quantity, which in my opinion and knowledge of the present facts must be reduced for the sake of truth. I will attempt to defend him on the same grounds against the exaggerations of the other side, against much unjustified censure, and thereby attempt in the end to gain and establish a conclusion that, if not completely covering the topic, as one likes to say of late, at least might lead to greater consensus than hitherto.

It is granted to any individual that he may have his own taste; and it is laudable to try to account for his own taste. But to grant a generality to the reasons through which one wants to account would have to make his the only true taste (if it were to be valid), and means leaving the bounds of the inquisitive amateur, and appointing oneself as an obstinate law maker.

The true judge of art deduces no rules from his taste, rather he has formed his taste according to the rules that the nature of things demands. (Lessing)25

In my previous letter, I tried to indicate a priori that—and why—Wagner’s program promises more than any music is in a position to achieve. Now my task is to prove it to you.

“The glorified nonsense,” professes the Viennese critic, “that surrounds the Wagnerian interpretation of his overture fades somewhat, however, if one remembers that this piece is put together from separate components, which, individually, take their attendant meaning from the corresponding places in the opera. Precisely because it is no introduction, but a compressed summary of the whole, the overture assumes an acquaintance with the complete opera to be understood.”

Now then, if that is so, one does not have the right to say: “It is a sorry effort pieced together without inner development, without organic execution that—one understands not why—breaks off suddenly!”

But similar judgments have been made about very many overtures by those without familiarity with the opera and on hearing them completely for the first time; among others, namely the great overture to Leonore; in Vienna the great master even had to banish it because of the same reproaches now being leveled from that city at the Tannhäuser overture.26 The Tannhäuser overture is not without inner development, not without organic execution, and besides it does not break off suddenly, but concludes because its life has been completed naturally, and one sees very well why it is completed.

First I want to prove this to you and thereby dismiss those complaints made about the overture wherever it has been heard without the opera. Only then will I allow myself to make some remarks and substantiate them through examples that situate the work in question in a canon of effective overtures, but in no way raises it above all precursors as the very best.27

The Overture is not without inner development, if with this term one means the reflection of the action. The Tannhäuser overture lives up to these demands as well as any other I know. You can see that if you read the program and track the tone pictures in accordance to them.

The Overture does not break off suddenly. It concludes in the same way the opera closes, with the Pilgrims’ return from their penitential journey to Rome, and the rejoicing at Tannhäuser’s atonement and the redemption of his spirit as it drifts away from the earth. One knows perfectly well why it ends; namely, because the action that it reflects has reached its end.

The Overture is not without organic execution, if by this we mean its technical form. Some principal ideas are set up and repeated often in order to achieve referentiality and roundedness, quite in the same way and form that other earlier composers crafted them.

You can convince yourself of all this by attentively observing the piano score, and it will arise by the by from my future letters.

Wagner therefore does not deserve the reproaches that have been made everywhere about his overture, when one could only hear it without knowing the opera; but at the same time you see that, with respect to the Tannhäuser overture’s setting and expressive purpose, he has not followed a new direction, not opened up a new path; rather, he went the way of all good earlier masters.

If, then, not excepting this overture, the effusive assurances of Wagner’s tremendous genius should be based on truth, as is still repeated sedulously by many, so can this genius be found only in a novelty and peculiarity of musical thought that far surpasses all prior achievements in its portrayal, instrumental coloring, harmonic and modulatory properties, in magically charming melodies, in hitherto unattained expressions of truth and hitherto unattained expressions of effect.

But let us leave these assurances aside and bring some facts before our eyes and eavesdrop on what our own senses feel and judge about it.

The Adagio is quite a popular melody, absolutely simple and flowing in its design. It belongs to the Pilgrims’ song. It is a good melody, expressive, harmonically and instrumentally interesting. It must please anyone who opens his ear and heart to it without prejudice. Yet I neither want nor am able to explain it to you as the best, most original, pleasing, and most deeply moving of all melodies that have appeared up to now. Judge for yourself.

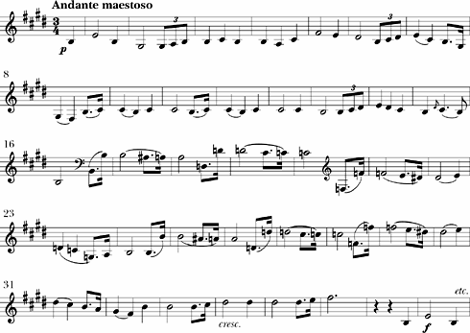

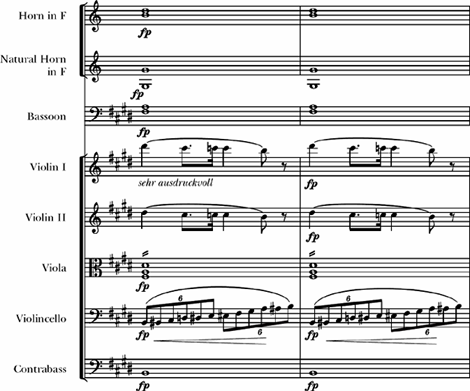

Example 1.

What follows is a repetition of the preceding material with a different accompaniment, which we can talk about later.

You see in passing that Wagner can certainly form clear and symmetrically structured periods and melodies, where he wants to. As mentioned above, Wagnerian melodies are not the best among all that exist. There are many that are equal to his melodies in value and effect, and some could be cited that surpass him in both respects. Listen to this melody, then listen to Weber’s played by the horns in the Adagio of the Freischütz overture, and ask your ear and heart which makes a more pleasing impression. The answer, I think, will turn out decisively in favor of the second.

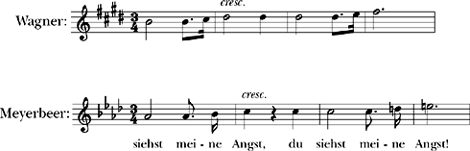

One can still doubt the constant originality of Wagnerian melody. Glance over at the final four measures. Do you not think of a composer who Wagner treats in the most contemptuous way in his writings? I mean Meyerbeer; I mean his “Mercy” aria.28 See for yourself:

Example 2.

Do not think I want to indict Wagner as a deliberate plagiarist. That would be more than ridiculous, it would be slanderous. Less injustice would be done were one to think: Meyerbeer’s phrase emerged from Wagner’s quill unconsciously through memory while he worked, and he regarded it as his own invention. One may accept this all the more easily since Wagner appears to be congenitally blessed in the highest degree with the belief that he is absolutely original, that he creates everything purely from his spirit, and his apostles do what is possible to sustain and secure him in this belief.

If this assumption should prove warranted, one might suspect that the contempt Wagner supposedly feels toward Meyerbeer’s works is not really all that intense, for musical thoughts that appear contemptuous to a great tone genius do not usually nest themselves in his head in order to dart out later in his own scores as reminiscences.

Nevertheless, I want to let this thought go as well. I want to suppose more in favor of Wagner than even his absolute admirers; namely, that Wagner has never heard a note of Meyerbeer.29

The irrefutable fact, however, remains: Wagner wrote down four measures whose novelty does not surpass everything previously achieved in music. Rather, he wrote down four measures that had already been born identically in the head of a composer (before him) whom he deeply despises.

Only four measures of preexisting music, to be sure!

But we encounter these four measures right in the first part of the first opera that should have forged the new direction: the Adagio of the Tannhäuser overture.30

This discovery will mean nothing at all for those to whom Tannhäuser is recommended as the opera of a highly talented composer. Similar things happened to the greatest musical geniuses of every age. But if one extols Wagner as the composer who leaves far behind him all that has previously been achieved in music, if Wagner himself tells us that all prior masters strolled about in error, went along entirely false paths, and that he first discovered and entered along the only right one, so he who follows him attentively may become somewhat suspicious when right at the entrance to the new route he catches sight of a little spot already seen in almost exactly the same form on earlier walks along well-trodden paths. So comes to mind spontaneously the old saying: “Nothing new under the sun!”

There are individual passages in music that make very particular impressions on individuals and elicit quite opposed opinions. The long violin passage in the Adagio of the Tannhäuser overture must belong to these, for it has been praised by one side just as warmly as it has been rebuked angrily by the other.31 There is nothing in this configuration that sins against any legitimate rule of art. It is clear in design and instrumentation. Wagner discloses its idea in his program: “It is the rejoicing of the Venusberg itself redeemed from the curses of unholiness, which we hear as Divine song. All pulses of life surge and bound to the song of redemption.” Reproachful judgments of this passage can only flow from individual perceptions precisely because it cannot be proved that the passage contravenes any essential rule of art. Of course, one cannot argue about the worth or shame of this passage with people who perceive differently. If you want to know my thoughts about it, I say to you that I like the idea as well as its musical symbolization very much indeed; the passage makes the same agreeable impression on me at every performance. Of all Wagner’s inventions, I regard this as one of his most characteristic, and concerning the fitting expression of the object, one of his most excellent.

On all technical points, the whole Adagio is absolutely perfect, and it is therefore absolutely perfect because it does not want to develop any new-fantasized rule of art, rather it follows in its whole structure the best of the old rules exactly. As mentioned earlier, its spiritual content is significant, and very agreeable poetically, musically, and formally.

If it were really Wagner’s innermost conviction that all previous musical forms are now defunct, and for that reason a new and living content can no longer be revealed in them, then in this Adagio our composer overturned his dictum through the facts of his own musical pen, for it presents precisely a new Content in traditional Form, as mentioned already.

And if Wagner’s admirers were really inwardly transfigured to such an extent that they could not accept any piece of music that appears in a traditional form, then this Adagio should arouse in them no pleasure at all, but merely revulsion.

Nevertheless, Wagner allows this introduction in his overture, and his friends will surely regard it not as a bad passage, rather as a very good one, or indeed, as the very best that has ever opened an overture, since in their eyes Wagner is the greatest composer.

I too regard it as one of the best, and so I agree, as do certainly all uninhibited musicians and connoisseurs not prejudiced against Wagner; even the public at large agrees with the most absolute of Wagner’s admirers.

Whoever can create such an Adagio, I would argue, must be a highly talented musical mind, and the despicable phrases that his opponents disseminate lock, stock, and barrel are no more justified than the effusive phrases of many of his most enraged defenders.

One can recognize and feel much—a great deal—in his works that contravenes the real rules of art, but he still is and remains a first-rate musical mind. It is only that he is not the greatest composer of all previous ages. I am afraid that I will be able to prove the latter remark to you through detailed analysis of just the Allegro of the Tannhäuser overture.

But that comes in the next letter.

One does not become acquainted with artworks when they are finished, one must grasp them in their process of becoming in order to comprehend them to some degree. (Goethe)32

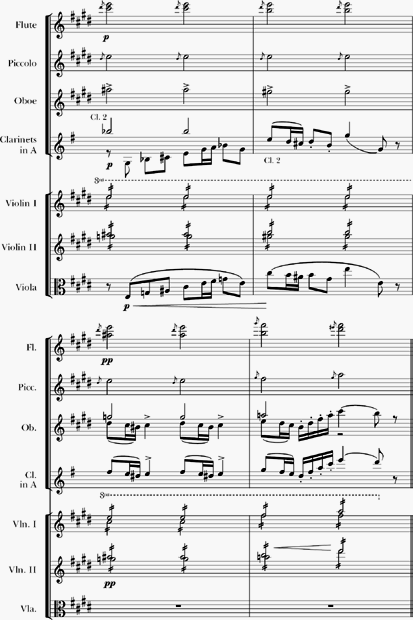

Do not be shocked when I tell you that today’s letters deal with little more than an analysis of the first sixty-one measures of the Allegro from the Tannhäuser overture, of which every detail will be subjected to such analytical precision and microscopic exactitude, in a way that perhaps no other comparatively small piece of a composition has ever been observed. The advantage of this approach will be clear to you in the next volume, where we can already bring to a close our considerations of Wagner’s two main works that have appeared so far.

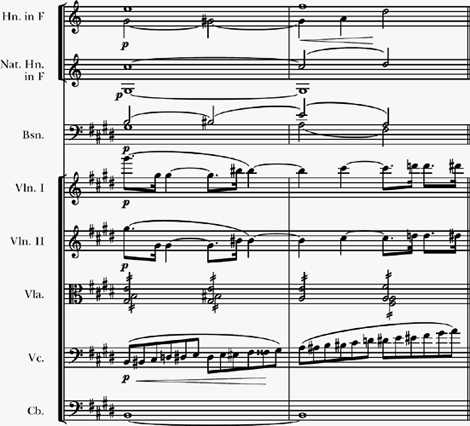

First look at the underlying material of the thoughts, the motives that form the basis of these sixty-one measures (Example 3).

You will not be able to say of any single musical figure viewed on its own that a similar or the same figure has never existed before; no single measure is absolutely new, indeed we and our forefathers have heard many of them very often.

You will object that this does not matter; that one arrives at the same result with the most genial works if one plucks and unravels them in such a way; that the genius may create the most original and noble composition from the same material with which a beginner or a dull-witted talent assembles only a trivial whole.

I will gladly tolerate this objection. I only wanted to leave nothing unexamined in a composer who accuses all his forebears of wandering down false paths, whom his devout supporters extol as the first and only true tone poet, so that I might uncover the point where the historically unprecedented begins.

Certainly Wagner cannot complain about unfairness if the material of his thoughts is declared no better and no worse than that of a Beethoven, C. M. v. Weber, and Schumann, among others.

Example 3.

Let’s see what sketch or design he made from this for his [musical] painting (Example 4).

Example 4.

From a technical aspect this design is new through its deviation from the previous way of constructing an overture. The sixty-one measures take up the space in which our best masters executed the main theme and transition. In place of this appears first an expanded section of three measures in which two ideas are telescoped together (1); two four-measure phrases follow from this (2 and 3); after which follow two sections (4 and 5). None of these five miniature pictures has anything in common with the others; each is of an entirely different nature from the others in shape and meaning.

If one wanted to start a speech in this way, it would go something like: “I went walking yesterday. The church was well attended today. It looks like rain. I’m happy. The green tree.” Here you have five short, consecutively stimulated ideas following each other; each is comprehensible in itself, but taken together they allow for no unity of thought.

The six musical thoughts following these five miniature pictures can be described as periods, but with these too, the feeling of being aphoristic remains, and so in these sixty-one measures eleven ideas flit over each other to us, which—however true you want each to be—do not combine into a clear organism, and must inevitably produce an impression of confusion.33

The result of such deviations from other masters’ methods of composition should not be to obscure constructions, but rather to progress genially toward the music of the future.34

“Every deviation from the norm has confused and repulsed the old hats,35 though it eventually was found pleasing and appealing to a later, riper time. The genius who opens new pathways has always failed to be recognized initially.”

This is the argument of those who attribute a higher artistic wisdom to themselves, and take a brighter view of the future than all those who cannot believe in Wagner’s absolute perfection as a composer.

It is a weighty argument, for it is backed up by many indisputable experiences. Therefore we want to get at it more sharply than others have hitherto, in order to see if what has been proved in some instances can be proved consistently. Truthfully, I am not writing these letters to encroach on Wagner’s actual merit, but always and only to defend the laws of art without whose preservation art cannot exist.

It is true, many artists’ innovations have only later emerged as successful innovations. But it is just as true that many innovations were and always remained unsuccessful.

I could give examples of the latter experience from all the arts; but I will cite only one from dramatic literature: Grabbe.36 This poet was greeted by some of the critics almost as a new Shakespeare. And truly, he did not lack for genial tendencies and flashes, or in strength and daringness, nor was he unwilling to disregard many hitherto effective laws of dramatic art. Those who denied he was a reforming genius, striding forth on a new path, were proved right. He did not achieve the goal that he might have been able to achieve if he had sought only to apply his ingenuity not in transgressing but in following the essential rules of art.

This argument is therefore not infallible. It has been proved, but also disproved.

But is this the case with Wagner? Does the present thrust him away apathetically? On the whole his works are received with approval wherever they are performed. He only recently reached the age at which a man is strongest and is already a celebrated figure as few earlier masters were at his age.

Those who oppose him do not deny his great talent and considerable success in some elements of his works; but they find weaknesses there as well, and cannot recognize in him the perfect composer against which all other masters sink into deep shadows.

There are details in Wagner’s compositions that at this moment do not please us and which we believe can never become beautiful. Among these displeasing constructions I count the part of the overture that I am discussing here, thus I want to produce some further supporting evidence for this opinion.

In his seventh letter, Lobe poses the question of whether artistic “innovation” must always exceed the “boundaries” of art. To illustrate his skepticism, Lobe likens arias by Mozart and Handel to the orderly construction of a house, and implies that Wagner’s imaginative freedom would fare less well in this particular simile:

If one scrutinizes a house according to the laws of natural consequence, and notices an irregularity in the parts and their relationships to each other, if e.g. in a row of eight windows one were only half the size of the other seven, this deviation from symmetry would incur one’s displeasure. How this would only increase if every window were of a different size and form, the first forms a regular square, for instance, the second an oblong, the third a circle, the fourth a triangle etc.!

The builder could produce such a house full of irregularities. He could install a chimney above the door, could craft a row of windows of the kind just described, and instead of being level, he could let this row be askew. His imagination could indulge in quite different shapes if he did not want to take into account the real needs of human nature, and wanted to carry out a capricious construction! Would one credit such a builder with having opened new paths with his art and having effected artistic progress?” I do not mean to say that—in a technical respect—the beginning of the Allegro of the Tannhäuser Overture is just as confusingly constructed as the house of capricious design mentioned in the previous letter; without doing injustice to the highly talented composer, however, I do believe that Wagner takes excessive leave of symmetry, of easily clear and comprehensible forms and division of thoughts.

One might reply: the idea takes precedence over technique, and the idea of the Tannhäuser Overture calls for a form different from the usual; it calls for exactly the form used here; the form must always conform to the idea, not the idea to the form.

Understood correctly, this dictum is true; misconceived and misapplied, it leads to the absurd; under the pretext that it had to be this way, it could easily excuse the most shapeless piece of hackwork as only able to emerge from the idea in this form.

Let us follow the new aestheticians behind even this barricade; do we see the ideas that Wagner expresses in these sixty-one measures?

His program specifies them:

a) At nightfall magical apparitions appear

b) a rosy scent of twilight swirls around

c) sensual sounds of joy reach our ear

d) the mad motions of a harrowingly voluptuous dance become faintly visible

The verbal expression of these four moments already lacks natural order; (b) would have to be first, (a) second. The spirit conjuror first lets incense rise up, and out of this the ghostly figures then emerge.

The program would therefore have to run:

a) At nightfall a rosy scent of twilight swirls around

b) magical apparitions appear

Aside from this, we now want to ask: Why did Wagner express these four ideas with words in normal language? Why does he comply as a writer to the recognized grammatical and rhetorical laws in the same way as every other sensible writer?

What would one say, for instance, if Wagner had expressed these four ideas in the following new way:

a) Fall at night around a scent

b) rosy of twilight swirls; appear apparitions

c) magical; sounds of joy etc.37

Would one be allowed to explain this way of connecting words as “the language of the future”?

Look again at numbers 1 to 5 in the sketch provided in our sixth letter, and tell me whether these short and heterogeneous mini-phrases do not produce an effect on your feelings not so very different from the effect of those rearranged verbal fragments above?

The thoughts are taken from the [composer’s] introduction. Look at this—you surely have the piano score—and compare it with the overture. Instead of finding some genial innovation in the latter, which we musicians are still simply unable to grasp, it makes much more sense to declare that the composer failed in transforming the introductory form into overture form. For we have already encountered many composers who wrote only operas and did not have any practice in submitting their thoughts to the stricter forms of the symphony or quartet, etc., while still maintaining some semblance of creative freedom. Wagner generally preaches with conspicuous zeal about freedom of form, and recently he proposed that the opera overture … should be eliminated, as he does himself. It might well be for this reason that he senses quite well the genus of a specific given form and wants to liberate himself from it through a new postulate. Goethe says: “Recent German artists declare any branch of art they do not possess as harmful and something to be beaten into submission.”38

And one more thing. Many people do not feel the lack of form. If they regard the expression as true, they are happy, and fail to see how others could wish for something more. We’ll let it pass. Appreciation for graceful musical forms is not just innate, it must also be cultivated through study. If this appreciation is sometimes lacking even in artists, its total absence in some contemporary critics need not surprise us. We might be more justly surprised, though, when the latter kind of inconsequential people declare everything they are unfamiliar with to be chimerical, and dub everyone a “pettifogger” who knows and has learned more than they.

And what contradictions the despisers of form get caught in! By their assurance, art up to now has closed itself off like an aristocracy, existing only for a small chosen few; progress must consist in making music into a general good for the people. Do they believe they are reaching this purpose by construing form ever more artistically and intricately, on the one hand, while on the other sometimes dissolving it entirely? Formations of such an incomprehensible kind as these sixty-one measures of the Tannhäuser overture will hardly ever become a general good for the people.

“Among the men of letters from the north”—Mme. Staël says—“exists a peculiarity that depends more, so to speak, on party spirit than on judgment.39 They are anxious about the defects of their writing almost as much as of their beauty; while they themselves should say, like a woman of wit, while talking about the weaknesses of a hero: he is great in spite, and not because of them.”

Up to this point, I have observed the material of this part of the Allegro and the design formed from it, and I have not been able to discover a perfected composition therein.

Let’s look further to see whether this perfection is perhaps produced by the addition of the other musical elements.

The last aesthetic letter attempted to outline the laws of modulation with respect to what is pleasing.40

Wagner declares these laws to be narrow-minded.

Observe his freer modulation.

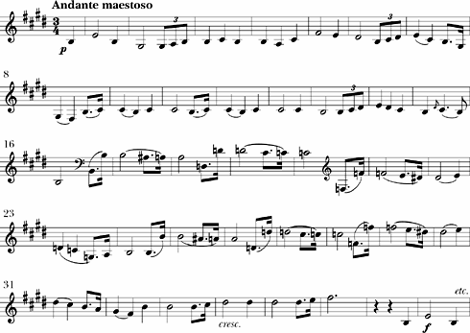

Example 5

In the first three measures the music already passes through five different keys. What a number of dissonant chords here! Forty-two in sixty-one measures! Among them, twenty-five diminished seventh chords, and fifteen based on B minor.

Consider that a diminished seventh chord belongs simultaneously to four different minor keys, and resolves equally legitimately to four different major keys; consider furthermore that if these customary resolutions are passed over, that is to say, the diminished sevenths progress to other diminished sevenths, the feeling of a particular key cannot arise in us at all: so it is easy to understand that on hearing these first sixty-one measures, one has almost no clue as to the principal key. Here we have diversity in excess, while unity is lacking altogether.

We already encounter this manner of modulating in the first sixty-one measures of the Allegro. Follow the dissonant chords through the whole overture, or through the whole opera (as I did), and you will feel that this utterly lavish use of dissonances becomes irritating for the ear, and must sap the expression of all meaning. Here too one speaks of what is desired by the “Idea.”

The demonic activities of the Venusberg, the whirring and straying about of magic apparitions, the mentally disorienting songs and dances, should all of this have been expressed in just one key?

In reply to this, we must say that eliminating one extreme does not entail summoning the other. Nobody can deny the dreadful truth of the devils’ chorus in Don Juan; the modulatory element is also employed there, but the feeling for the principal key, D minor, remains. Keys and modalities arose from the mind’s need to bring diversity into unity. The eradication of this achievement—the transition back from the fixed and particular into the wavering and indefinite—can never herald an improved system.

There is no doubt that the unclear design here is made no clearer through the use of modulation; rather it is obfuscated further. Thus the only remaining question is whether the instrumentation might allay this lack of clarity.

No expert will want to dispute Wagner’s knowledge of the laws of instrumentation; his operas contain many interesting and effectively colored sections; the impartial listener cannot concede, however, that he portrays through the orchestra the outline of his thoughts in the most perfect way throughout, i.e., true for feeling and for mind, while equally clear and pleasant for the ear. The sixty-one measures offer as much evidence for one truth as for the other.

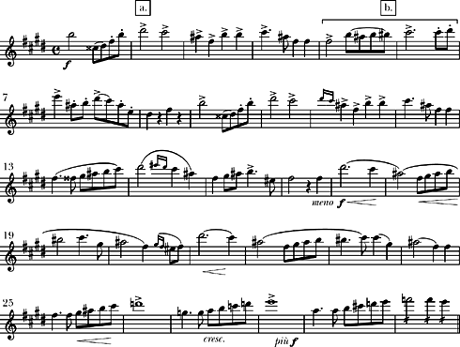

The most exquisite passage in these measures seems to me to be the following (Example 6).

One really does seem to see though one’s ear the rosy scent of twilight, and though truth of expression is undeniably present, the ear is equally won over by the pleasing sonority and clarity of the music.

That the divisi effect of the violins is no invention of Wagner’s, but has already been used by C. M. v. Weber, Mendelssohn, and Berlioz to most marvelous effect, I repeat not in order to diminish Wagner’s achievement, but rather to put it in a proper perspective.

On the other hand, you can judge the following passage through a mere observation of the score (Example 7).

In itself, the figure in the flutes and oboes is ineffective, worn-out, and fails to conjoin with the figures of the other instruments either with respect to rhythm or sound quality to produce an agreeable overall picture. Observe the melody in the third and fourth measures, which the oboe and clarinet play in unison. This unison becomes unpalatable for the ear in the fourth measure at the clarinet’s upward-shrieking notes and the oboe’s spiky sharpness. I know perfectly well that the composer wanted to characterize the wild bacchanal-like singing, but we must regard it as an eternally fundamental principle that under no pretext should a composition offer unpleasant sounds to the ear.

Example 6.

Example 7.

Above all things, one expects from the instrumental composer a precise knowledge of that which each instrument is able to achieve according to its nature. If he writes an unplayable passage for any instrument, he proves thereby that he is not well acquainted with its technique.

Take a look at the cello figures in the following passage, and think about the tempo at which they ought to be performed.

Example 8.

The greatest cello virtuoso cannot hope to play such figures (with their mixed succession of diatonic and chromatic intervals) purely and clearly at such a fast tempo. You can well imagine what a tonal mishmash results when this is played by three or four cellists in the orchestra at the same time, and anyone with a musically educated ear can hear this in performance. To be sure, this blending together of notes will be less noticeable to the unschooled ear, as a thick veil is thrown over it by the sustained notes of the four horns, two bassoons, and double bass, as well as the sixteenth tremolo of the triple-stopped viola notes; and the violin melody also draws the ear’s attention away from it. Precisely from this, however, composite sound pictures [Gesammtklangbilder] arise, whose labeling as “muddled din” is not unjustified.

Incidentally, compare this cello figure with the following from Weber’s Euryanthe.41

Example 9.

I set no great store by such similarities. Whoever is familiar with older music knows that hardly any composer featured more conspicuous reminiscences than—Mozart. This remark should only be further evidence of the truth that no artist can tear himself away entirely from his precursors, and be new through and through. In a later letter, I will bring more persuasive proof for this proposition when applied to Wagner. For the time being, it is enough to admit that even Weber’s figure, cited here, is hard to perform. However, it does not pose nearly the difficulties that Wagner’s figure does.

Purification of art is the great word by which Wagner denotes his mission. At times, however, his actions stand in direct contradiction to it. Whoever thinks he can find more purity in such passages as the two adduced above than in the artistic creations of our noblest masters is someone with whom we no longer wish to argue.

Purification of art! But surely of orchestration as well?! And then such pictures as these, in just one small section of the overture! —But consider the scores of Tannhäuser and Lohengrin from the point of view in which this new “art purification system” is meant to be revealed! Truly, we hear things asserted whose direct opposite is plainly apparent for those with eyes to see and ears to hear—as if all true musical knowledge had been lost.

The sixty-one measures have led me to speak at length. I will be able to be all the more concise about the remaining part of the overture. Ideas that are somewhat insufficient at the beginning of a piece of music can in the course of the work perhaps be enhanced through recurrence and further development. This remains for us to investigate in the Tannhäuser overture.

After the sixty-one measures, Wagner stops deviating from the customary form. He delivers a clearly constructed second group, a Gesangsgruppe based on Tannhäuser’s love song, and—like other masters—in the dominant key. Our composer has been accused of wanting to eliminate melody in his artwork of the future because he is unable to compose any. I will show you later some of his melodies that belong to the most deeply stirring and simplest that have ever been sung by a tone poet.42

One would not deny the name melody, for instance, to Tannhäuser’s song (Example 10).

I can, however, adjudge this melody as neither more charming nor more extraordinarily original than several of those by earlier masters. Consider Adolar’s song of praise to his Euryanthe (Example 11).43

The spiritual similarity of both melodies jumps right off the page at you. The creator of this melody could just as well be Wagner as Weber, or Weber as well as Marschner. But compare the measures marked “a” with those marked “b” in both melodies, and you also find something certainly technically akin. Every impartial listener must admit that here one is again concerned with an extended musical thought that exceeds the good structures of earlier masters in neither form nor content.

Example 10.

Example 11.

Thereafter, Wagner repeats and develops the material thematically.

To be sure, after attentive and frequently repeated study, one arrives at the same defense I proclaimed in contradiction of the Viennese critic in the fifth letter—namely that the Tannhäuser overture lacks neither inner development nor organic execution; nonetheless I must insist that it is in all respects more contrived and complicated than the best of other masters, and therefore cannot and never will be regarded as the most perfect of all overtures.

This is the only way in which the many brusque judgments rendered about this overture explain themselves. I have already shared the one from Vienna with you. One from London is still more terrible; there the overture is called a downright noise that confuses the senses.

Here again one might refer to other, similar cases, e.g., to the three Leonore overtures by Beethoven, that likewise first found only disapproval, but now please universally.

The comparison, though, is not completely correct. The Leonore overtures—when also heard without the opera, and for the first time—were never disliked by connoisseurs; on the contrary, they aroused the applause of all competent judges immediately. That could not have been otherwise, for there resides in the individual ideas of the overtures a graceful breath of melody alongside deep expressions of truth; my feeling is that the Tannhäuser overture lacks this component.

But let us at last illuminate this favorite objection—that “things were just the same with the works of other geniuses at the beginning!”—from a new point of view.

If it did turn out this way for several geniuses with one or another of their works—for we cannot claim that it is so for all geniuses with all of their works—should we not then ask at least once whether a genius absolutely must fare like this? Whether a real musical artwork can be produced under any other condition than that of total lack of initial recognition? Or whether this in fact documents a weakness of the artist, that he can form a product in no other way than that which on first appearance more likely repels the public rather than attracts them?

Works such as Goethe’s Egmont, Schiller’s Maria Stuart, and many other dramatic poems did not need the future; they pleased at once. The statues of Canova and Thorwaldsen found immediate recognition.44 And how do the great actors fare with such absolute maxims about the future? If the roles portrayed by a Garrick, Iffland, Devrient, Schröder-Devrient had repulsed their contemporaries, in what way would they have ever pleased and been recognized by posterity?45

It remains an established truth, then, that artworks can be created whose worth and effect are apparent on their first appearance.

Through frequent contact and habit, an initially rejected entity can become likable, and through clever commentary many things become comprehensible. Just because this happens now and then, must it therefore be a necessary attribute of real artworks? I ought to say that creations which one must first become used to and which require commentaries in journals before they ever get a foot in the door (or as now happens more often, enormous encomiums), do not at least earn a preference above those artworks that are just as valuable, and immediately find recognition and give pleasure without such assistance.

Instead of excusing the umbrage aroused by what is complicated and hard to understand with the phrase: “Other geniuses fared no better!” it would be much better to say: this artist has surpassed his predecessors by understanding how to sensualize the deepest truth in the simplest, purest, most graceful forms, so that the whole world can instantly understand and completely enjoy them.

That would be real progress in my opinion; it would be the composer’s most beautiful and most sublime task. Wagner did not set this task for himself, or at least he has not yet solved it. There are passages to be found in his works that are formed more artificially, confusedly, and incomprehensibly than everything that has been written so far in a similar way. And continuing to explain this as the effusions of a higher artistic spirit (as has happened up to now) and attempting thereby to entice talented young people on the same path can surely lead to no refinement, no purification, rather only to the decay of art.

“In every type of spiritual development,” says Friedrich v. Schlegel, “there is, as in the graduated progression of nature, a moment of bloom and a highest point of completion that manifests itself in a beautiful perfection of form and of language.”46

No composer has attracted such an exclusive and immoderately ennobling party as Wagner. It is not enough for them to compare and put him on the same level with other, perhaps even the most highly recognized geniuses; no, he is treated as incomparable, as though his like had never existed before.

Likewise it is also not enough to praise Wagner’s striving after proper musical characterization (up till now his weakest side in my view); no, he is to have achieved this with a formerly unimaginable perfection. If one but opens the score or the piano arrangement to a passage like this one, or listens to it in the theater:

Example 12.

one must confess first that it is music, good music that cannot be mistaken for anything but a significant talent; but to insist that such music arises from such an ineffable, incomprehensibly effusive nature that nothing similar could ever have occurred to the mind of the greatest geniuses of earlier times—this can be called nothing but sheer apotheosis. The natures of a goddess and an earthly woman are certainly far apart from each other.

The enchanting, seductive Venus might have all the feelings and passions of the earthly woman; the characteristic difference between both, however—the same fit of temper over a renegade lover in terms of melody, harmony, instrumentation, etc.—would certainly have a different appearance for the Goddess and for the mortal beauty.

Look at the beginning of the duet between Tannhäuser and Venus in the example above.

You only see the vocal part and the accompaniment in the piano score, but even this will be enough to prove that the melodic and rhythmic accents of neither the singer Venus nor the accompaniment show any features that would particularly differentiate the Goddess’s anger characteristically from that of any single earthly female.

It is true, in Lohengrin Elsa is different from Ortrud and Lohengrin is different from Telramund when they appear in moments of calm emotion. At the apex of passion, however, they all declaim similar melodic phrases without characteristic difference; and Elsa has the same accompanimental figures, the same strong orchestration as Ortrud, Lohengrin the same as Telramund.

Look at Elsa’s part in the following section (Example 13).

Example 13.

That is the same high pitch of passion as voiced by Venus, Ortrud, Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, and Telramund during agitated moments.

And, quite apart from these particular examples, I would ask if all of Wagner’s characters are more sharply portrayed than Mozart’s Sarastro, Moor, Papageno, Tamino, the Priests, the three women, the three boys, Pamina, the queen of the night; than Don Juan, Leporello, Zerlina, Elvira, Masetto, Ottavio; than Belmonte, Constanze, Pedrillo, Blonde, Osmin; than C. M. v. Weber’s Max, Caspar, Agathe, Aennchen; Euryanthe, Eglantine, Adolar, Lysiart; than Méhul’s characters in Joseph in Egypt; Cherubini’s characters in Les deux journées, etc.?

But enough!

With an artist as highly talented as Wagner it is no pleasant business to have to emphasize not his many strengths but to draw attention instead to his weaknesses. Whoever truly loves art and artists, however, can do no other. Wagner provokes the comparison of his music with his doctrines by the way he indicts all previous masters for their misconceptions.

He possesses a great characteristic—energy. It is rare in our time, very appreciable in itself, and it wields an almost irresistible power over the majority of people. If he always knew how to hold this energy in the necessary bounds, where it remains energy without being driven into Schwärmerei or even fanaticism, he would be all the better for it.

Admittedly, the controversy that he aroused skillfully enough through his writings—like the clamor that his followers have raised around him—has awoken an extraordinary degree of curiosity about his operas.

Everyone simply must hear and see them, and it is entirely natural that they appeal everywhere through their real poetic and musical worth.

But the huge torrent of enthusiasm that has been aroused partly artificially will drain away. When curiosity is sufficiently satisfied, and through frequent enjoyment of the opera, the public does not merely catch several beautiful aspects, but is also able impartially to sense the weaknesses. Wagner’s works will join the ranks of the better works, but will no longer be vaunted as the highest blossoming of our art. The real works of earlier masters will be vindicated, and the future?—will create its own works.

Certainly, Wagner has written no drama of the future—rather, he has written dramatically and musically effective operas, the understanding and enjoyment of which require no future generation. The present understands and grasps their merits, which are often of the best kind; it also recognizes and grasps the weaknesses, however, which at times are of a very present kind. On the whole, this will have to be the final assessment. It has already become such for everybody not exclusively caught up in the pro or the contra, in one-sided ways of viewing or willing or feeling, but who has and wants to have ears open to both.

I regard Wagner as one of the most significant, most powerful, and most energetic artistic natures of our time, not as the only one. Robert Schumann is completely equal to him musically, superior in technique and more universal in his creativity, even if he lags behind Wagner in the field of opera.

I cannot, however, hold back something in conclusion:

“Geniuses alone ruin taste because taste does not exist without them, and geniuses can only ruin taste if they misuse their powers. There are two ways in which this is possible, through false ends and through false means. If a vessel is already full, and one pours in more, it overflows. If the mind full of power has already achieved its aim and wishes to go still further, it progresses beyond the goal, into an unnatural land of false taste as an end. If it chooses a will-o’-the-wisp as a purpose, or wants to fly to the sun with Icarus’s wings, so its name will signal swamp and sea, for it has chosen false ends and will succumb on the way. Or a genius has a noble, true goal before him, only he has no guide. In the initial heat of inspiration he takes the wrong path, realizes too late he has strayed. As a genius, he has achieved some good on the false path; he looks back and does not have enough greatness to give up everything and come around to a better pathway. Perhaps irresistible false objects tantalized him along the way. With his powers he believed himself capable—on this wrong path—of going where no other had gone before him. He strode onward and with his noble powers became an archetype for false taste, a seductive, negative greatness. That is the sad theory of corrupt taste of all ages, seen from the genius’s point of view.”

It is not me saying this; it was written many years ago—by Herder in his “Causes of the Decline in Taste.”47

1. Lobe published his Fliegende Blätter in three volumes: 1 (494 pp.) in 1853-54; 2 (509 pp.), 1855-57; 3 (112 pp.), 1857. The Briefe über Wagner appeared in the first two volumes: 1:411-29, 444-65; 2:27-48. A complete itinerary of these volumes and indeed everything Lobe published is given in the bibliographic appendix of Torsten Brandt, Johann Christian Lobe (1797—1881): Studien zu Biographie und musikschriftstellerischem Werk (Göttingen, 2002), 317-31.

2. See David Blackbourn, The Long Nineteenth Century: A History of Germany, 1780—1918 (New York and Oxford, 1998), 106-20.

3. J. S. Dwight, “Music Journalism in Germany,” Dwight’s Journal of Music 6 (13 January 1855): 115.

4. “Please also give Lobe my warmest thanks,” he wrote to Liszt, “his judgment both surprised and pleased me very much.” Wagner to Liszt, 24 December 1850, Zurich, in Sämtliche Briefe (Leipzig, 1867-2008), 3:486. Lobe’s review, “Das Herderfest in Weimar,” appeared in the Signale für die musikalische Welt 37 (11 September 1850): 345-50.

5. Lobe, “Ein Verteidiger Richard Wagner’s,” Fliegende Blätter für Musik 1 (1853): 54-56. Schaeffer’s review sets out from the entirely incorrect assertion that “Wagner dedicated a special work—Opera and Drama—to precisely this [music and poetry], and within it, declared their relation to one another as their only possible position in the ‘Drama of the Future.’ But he did not stop at that, rather he simultaneously aspired to the realization of his principles in original composition, particularly in Lohengrin and Tannhäuser.” See Julius Schaeffer, “Über Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin, mit Bezug auf seine Schrift: ‘Oper und Drama,’” Neue Berliner Musikzeitung 20 (12 May 1852): 153.

6. Lobe, Musikalische Briefe: Wahrheit über Tonkunst und Tonhünstler, von einem Wohlbekannten (Leipzig, 1852; 2nd ed., 1860), 277.

7. J. C. Lobe, “Fortschritt,” Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 50 (1848); “Erster Artikel,” 49-51; “Zweiter Artikel,” 65-69; “Dritter Artikel,” 169-73; “Vierter Artikel,” 337-41; “Fünfter Artikel,” 581-87, 598-601, 615-28, 641-46, 673-78; here, “Dritter Artikel,” 169.

8. J. S. Dwight, “Music Journalism in Germany,” Dwight’s Journal of Music 6 (1855): 115.

9. Lobe, “Ein neuer Prophet der Zukunft,” Fliegende Blätter 2 (1856): 314-19.

10. Lobe, Musikalische Briefe, 33-34.

11. Wagner, “Ueber Inhalt und Vortrag der Ouvertüre zu Wagner’s Tannhäuser,” Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 3 (14 January 1853): 23-25.

12. Lobe, “Fortschritt. Vierter Artikel,” 341.

13. See Eduard Bernsdorf’s warm review of a reissue of several of Lobe’s essays as “Consonanzen und Dissonanzen: Gesammelte Schriften aus älterer und neuerer Zeit” and his specific description of Lobe’s approach as a “Neueinführung,” in Signale für die Musikalische Welt 67 (6 December 1869): 1057-58, here 1058.

14. “Letters About Richard Wagner, to a Young Composer,” New York Musical Review and Gazette (25 August 1855): 284.

15. J. S. Dwight, “Music Journalism in Germany,” Dwight’s Journal of Music 6(1855): 115.

16. In Lobe, “Aesthetische Briefe: Erster Brief,” Fliegende Blätter 1 (1853): 188.

17. “Einige Wenige haben diese Art zu denken, und Viele wollen sie zu haben scheinen; diese machen das Geschrei und geben den Ton; der größte Haufe schweigt und verhält sich gleichgültig, und denkt bald so, bald anders.” Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Gesammelte Werke VI, Hamburgische Dramaturgie, no. 11, (Berlin, 1767; repr. 1954), 63.

18. The untranslatable term “Tongeister” implies the lofty minds of great composers.

19. For detailed discussion of the term “absolute music” and its historical usage, see “The History of the Term and Its Vicissitudes,” in Carl Dahlhaus The Idea of Absolute Music, trans. Roger Lustig (Chicago, 1989), 18-41.

20. Wagner’s program for the Tannhäuser overture, “Ueber Inhalt und Vortrag der Ouvertüre zu Wagner’s Tannhäuser,” was written for his three-day festival in Zurich on May 18, 20, and 22, 1853. The festival featured concert performances of excerpts from all three of Wagner’s Romantic operas, and is given in his letter to Liszt of 3 March 1853. See the translation of Wagner’s program to the Tannhäuser Overture included in Part VI of this volume.

21. Franz Brendel alluded to the Viennese critic’s phrase “überwundenen Standpunkte” (dated or outmoded standpoints) in his 1859 address to the Leipzig “Musicians’ Assembly” (a translation of which can be found below in this section), by which time it had become closely associated with Brendel’s advocacy of the “modern school” and his ideological dismissal of musical conventions and received styles.

22. Lobe, “Hektor Berlioz,” Fliegende Blätter 1 (1853): 86-105.

23. Lobe refers to the opening dramatic effect in Haydn’s Creation.

24. Wagner had no sympathy with the poetic notion of unconscious creation. Writing to Eduard Hanslick, he explained: “Do not underestimate the power of reflection: the unconsciously created work of art belongs to periods which lie far away from our own: the work of art of the most advanced period of culture can be produced only by a process of conscious creation.” Wagner to Hanslick, 1 January 1847, Dresden, in Selected Letters of Richard Wagner, trans. and ed. Barry Millington and Stewart Spencer (New York, 1988), 134.

25. “Es ist einem jeden vergönnt, seinen eigenen Geschmack zu haben; und es ist rühmlich, sich von seinem eigenen Geschmacke Rechenschaft zu geben suchen. Aber den Gründen, durch die man ihn rechtferrtigen will, eine Allgemeinheit ertheilen, die, wenn es seine Richtigkeit damit hätte, ihn zu dem einzigen wahren Geschmacke machen müßte, heißt aus den Grenzen des forschenden Liebhabers herausgehen und sich zu einem eigensinnigen Gesetzgeber aufwerfen. / Der wahre Kunstrichter folgert keine Regeln aus seinem Geschmacke, sondern hat seinen Geschmack nach den Regeln gebildet, welche die Natur der Sache erfordert.” Lessing, Hamburgische Dramaturgie (No. 19), in Gesammelte Werke (Berlin, 1954), 6:100-101.

26. A reference to Beethoven’s Leonore Overture no. 3, which was eventually replaced with the simpler, less dramatically freighted Fidelio Overture, when Beethoven’s opera was revived under the latter title in 1814.

27. Lobe’s term Reihe (canon) does not imply canon formation as the notion is understood in modern criticism, but merely a series of related overtures. His concern is to insert Wagner’s composition into a music tradition that the composer himself vehemently rejected.

28. Isabelle’s cavatina “Robert, Robert, toi que j’aime” (mm. 15-18), the refrain of which runs “Grâce, grâce pour toi-même.” From Act 4 of Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable.

29. Lobe was of course well aware of Wagner’s contempt for Meyerbeer, and so rather than making a patently incorrect statement here, he is posing a hypothetical scenario: let’s imagine, for the sake of argument and neutral criticism that Wagner had not heard a note of Meyerbeer.

30. Wagner’s latest works, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, were commonly received and assessed by German critics as exemplifications of Wagner’s theory for Worttonsprache, Versmelodie, orchestral dialogue, and for his aspirations toward drama as laid out in Opera and Drama. They were by far the two most commonly performed of Wagner’s operas in Germany during the 1850s, yet Wagner is at pains to point out in private correspondence that they antedate his theories (most notably a letter to Adolph Stahr on 31 May 1851), and he publicly distanced himself from them in the preface to the French translation of Tristan, Der fliegende Holländer, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin of September 1860: “[I wish] to draw your attention to the great mistake which people make, when they think needful to suppose that [Holländer, Tannhäuser, Lohengrin] were written with conscious purpose after abstract rules imposed upon myself… my system proper, if so you choose to call it, finds in those first three poems but a most conditional application.” See “Zukunftsmusik,” in Judaism in Music and Other Essays, trans. and ed. William Ashton Ellis (Lincoln, Neb. and London, 1995), 295, 326.

31. Lobe alludes to the persistent figuration in the violins that decorates the Pilgrims’ Chorus theme in the introduction and coda to the overture—an effect that struck listeners from the beginning, and created a similar sensation in Franz Liszt’s difficult piano transcription of the work.

32. “Kunstwerke lernt man nicht kennen, wenn sie fertig sind, man muß sie im Entstehen aufhaschen, um sie einigermaßen zu begreifen.” Goethe to Zelter, Weimar, 4 August 1803, in Der Briefwechsel zwischen Goethe und Zelter, 1799-1818, ed. Max Hecker (Frankfurt am Main, 1987), 1:44.

33. Lobe’s use of the term Perioden (periods) in this sentence is idiosyncratic, perhaps indicating that he wants to mirror Wagner’s use of old forms in new ways through his use of analytical terms.

34. Lobe’s reference here to “die Musik der Zukunft” is among the earlier instances of this quasi-Wagnerian term which, as “Zukunftsmusik,” would become a standard weapon in the arsenal of anti-Wagnerian criticism by the end of the decade

35. Lobe’s Zopf refers to the aristocratic, old fashioned stereotype of “alte Zopf” which is the German phrase for a pre-French Revolution aristocratic wig for men. In Lobe’s usage, it connotes artistic and political outdatedness and conservatism in people, or an antiquated custom. In his essay on conducting from 1869, Wagner used the term to refer to a typical German Kapellmeister—“sure of his business, strict, despotic, and by no means polite”—who displayed an “old-fashioned” attitude toward modern music. See Wagner on Conducting, trans. Edward Dannreuther (New York, 1989), 2.

36. Christian Dietrich Grabbe (1801-36), a paradigmatically Romantic dramatist: eccentric, ambitious, rebellious, and short-lived. He himself wrote an essay “Über die Shakespeare-Manie” in the 1820s, and Heine—an admirer of Grabbe’s poetry—likened him to a “drunken Shakespeare” because of his “tastelessness, cynicism, and exuberance.” See Heinrich Heine, Werke und Briefe, ed. H. Kaufmann (Berlin, 1962), 7:194.

37. “(a) Beim der Nacht Einbruch auf ein Duft