Franz Brendel (1811–68) took over the editorship of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik from Robert Schumann at the end of 1845—Schumann had founded the journal in Leipzig in 1834, to provide an alternative to the conservative Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (1798–1848). The twenty-fifth anniversary of the journal’s founding was the occasion for the Leipzig Tonkünstler-Versammlung (musicians’ assembly) of June 1859, at which Brendel delivered the opening address: “Advancing an Understanding.”1 The talk’s historical importance resides in Brendel’s coinage of the designation “New German School” for the music of Wagner, Liszt, and Berlioz, to replace the term “Zukunftsmusik” (music of the future) that the opposition had imposed upon the compositions and aesthetic writings of the progressive party.

It made sense that Brendel should open the assembly, since he had been responsible for the Leipzig Tonkünstler-Versammlungen of the late 1840s; moreover, he had dedicated the Neue Zeitschrift to the new movement in the early 1850s, tirelessly writing and publishing on behalf of Wagner and Liszt.2 In other words, Brendel and his journal had become recognized respectively as the spokesman and the organ for the progressive cause in music. However, this central position also meant that the opposition—in large part music critics and musicians from northern Germany, the Rhine and Vienna—would focus their attacks on the editor. A vehement polemic battle between “progressive” and “conservative” forces had indeed raged in the press of Central Europe since at least 1853—this is the point of departure for “Advancing an Understanding,” which recent scholarship on the one hand has dismissed as “drivel,” and on the other uses as the platform for developing elaborate aesthetic systems for the New German School.3 However, beyond the important neologism coined here, the address is also a reasoned argument aimed at both supporters and opponents of the new direction in music, a structured discourse that presents the editor’s construction of music history and the essential role of the written word therein, recapitulating the nature of the aesthetic dispute and laying out the groundwork for a reconciliation. Its value resides in the articulation of Brendel’s historical and polemic perspective on the positions of the “New Germans” and their opposition. That Brendel appeared to be working toward a reconciliation without making any real concessions to the opposition was not lost on them, for the well-known riposte (or “manifesto”) in May of 1860 was specifically leveled against the direction of Brendel and his journal. The manifesto appeared on 6 May 1860, in the Berliner Musik-Zeitung Echo and was signed by Brahms, Joseph Joachim, Julius Otto Grimm, and Bernhard Scholz. However, the New Germans somehow came into possession of a pre-publication copy of the manifesto and published a parody of it in the Neue Zeitschrift two days earlier.4

Several aspects of “Advancing an Understanding” merit special consideration. In the opening paragraphs, Brendel clearly valorizes “the printed word” in his apology for the newest movement in music, noting how Schumann importantly pioneered the calling of composer-critic yet remained mired in subjectivity and caprice in his writings. Brendel takes credit for having introduced a more objective, “scientific” approach to the critical and aesthetic side of writing about music—the desire to bring about uniformity on that basis led to the first Tonkünstler-Versammlung, in 1847. For Brendel, this was the age of informed writing on music, when composers articulated their principles in print and critics relied upon reason in their judgments. It might seem strange that Brendel mentions only one composition (Lohengrin) in the entire address, but one must bear in mind that in 1859 relatively few recent works of Wagner and Liszt were known, the opposition was not championing any composer of its own (Brahms had yet to make a significant appearance), and—most important for Brendel—both Wagner and Liszt had significantly committed their aesthetic ideas to print.

Brendel presents a four-step plan to realize the reconciliation. The first phase involves “working toward the elimination of countless misunderstandings” (on the part of the opposition). Then he turns to the need to replace “naturalism” (Romanticism) and its world of “instinct” and “sensoriality” with “rationalism,” “a thinking comprehension of art,” which includes the practical reorganization of musical life. Once that basis of principles is achieved, it will be possible to determine whether the music itself conforms to them (he mentions no works in this short third section). Finally, he talks of the need to purge the field of things that remind us of the old battle. Here he proposes replacing the designation “Zukunftsmusik” with New German School. Brendel’s final major argument regards the suitability of that term to collectively represent the three leading composers of the new direction (Wagner, and the unnamed composers Liszt and Berlioz), which he justifies on the basis of what he calls the “universal German.” This category enables artists of foreign birth to adopt the German spirit and intellect, whereby they become just as German as the “specifically German.”5

Brendel is not particularly helpful regarding the neologism New German School. After establishing the indebtedness of the movement’s three coryphaei to Beethoven, he defines the term as “the entire [German musical] development after Beethoven,” the German North having taken the lead from Beethoven after the “Italianate” Classical era of the Viennese masters. If we take him at his word here, Brendel would have to include Schumann and even Mendelssohn among the New Germans, at least as transitional figures.6 He may have replaced “Zukunftsmusik” with another name for the progressive movement, yet when one investigates more closely, the new designation raises as many questions as the opposition’s term. Indeed, Brendel seems to distance himself from any deeper interpretation when he wrote in the 1860 edition of his Geschichte der Musik, “As is generally known, … the Wagner-Liszt school… has now adopted the name of the ‘New German [School],’ for no other reason than to dispel invidious memories attached to the distasteful word ‘Zukunftsmusik.’”7 Elsewhere, Brendel does not appear to have used his own neologism, whether in the Geschichte der Musik or in the opening address to the next Tonkünstler-Versammlung, in Weimar in 1861.8 By that time, he had turned his attention to the new organization called the Allgemeine Deutsche Musikverein, which was supposed to put the principles of the progressive party into practice and realize Brendel’s own vision for the gathering of musicians. Certain progressive apologists like August Wilhelm Ambros and Louis Köhler did write prominently about the New German School in the 1860s, yet it was a later generation of music historians and aestheticians—arguably beginning with Hugo Riemann in 1901—that would consistently apply the designation to the three composers and their followers.9

That Brendel concludes the address with a complaint about the tone of debate in the musical press rather than a panegyric to the just-named New German School reflects his priorities in “Approaching an Understanding.” He was primarily concerned with establishing a framework for discussing—even debating—the “music of the future.” Elsewhere he had already presented the aesthetic agenda for the progressive movement—here Brendel needed to establish his credentials and to muster support as prophetic spokesman for the party (after all, he had assumed the power to name it), to show himself to be a reasonable, logical participant in the debates, and to cast whatever aspersions possible at the opposition, even while maintaining a surface position of evenhanded neutrality. In the final analysis the address served musico-political purposes, as the opposition perceived and as they reinforced in their 1860 manifesto. It also provides valuable insights into how Brendel—leading apologist for the “New Germans”—perceived the movement around Liszt and Wagner to have taken shape and defended itself.

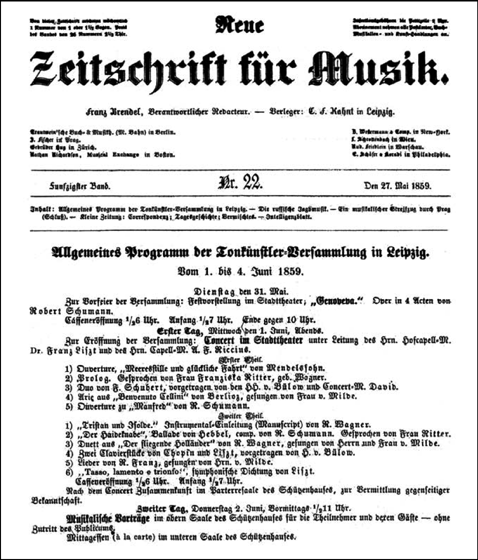

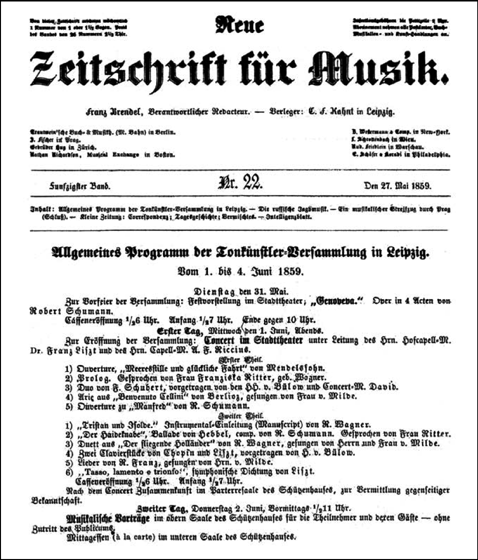

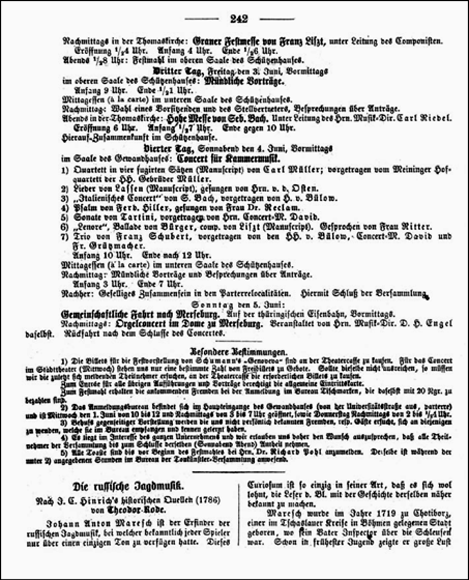

The programming of the concerts that accompanied the Tonkünstler-Versammlung was intended to underline the official message of reconciliation between old and new; between canonic “old masters” like Bach, early traditionalist Romantics like Schubert and Mendelssohn, and modern “New Germans” like Liszt and Wagner. Schumann, the founder of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, figured prominently. The programs for these concerts are reproduced below.

Concert program for the Leipzig Tonkünstler-Versammlung, June 1-4, 1859.

Concert program for the Leipzig Tonkünstler-Versammlung, June 1-4, 1859.

FRANZ BRENDEL

Advancing an Understanding

Address to the Opening of the Tonkünstler-Versammlung

Delivered in Leipzig on June 1, 1859

Esteemed Assembly!

A significant stage in the history of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik provided the initial, ostensible occasion for this assembly: the twenty-fifth anniversary of its founding. You have come here to celebrate that anniversary together with us.

Since I am the one most directly involved in this event, as the person who initiated the celebration, it is incumbent on me to present you with its concept and intention. It is my task to lay out the inner significance of the activities of the assembly and to demonstrate how I consider it to be a beneficial and appropriate means for engaging with the musical conditions of the present.

Before I turn to this, my main topic, however, it is my agreeable first task to welcome you most heartily. I hope that you will like it here and that we will be in the position to meet your expectations to some extent. It is also my pleasure to thank you for the interest you have shown by attending this event, all the more so because of the heightened difficulties of the general conditions that prevail at the moment and that nevertheless did not deter you from coming.10

As regards more particularly the task just identified, this must inwardly result from the journal’s development, even as it is externally determined by a stage in the history of this organ.

To this end we hardly require a detailed consideration ofthat which came before. I will only recall what is generally known when I direct your attention to the stages through which the journal has passed up to this point.

You know the circumstances under which Schumann began, how it was a matter of regenerating music criticism and at the same time pioneering a new direction in the art of the time. A general flagging of effort had taken hold both in the realm of musical production and that of criticism, the latter especially here in Leipzig. Concerning production, one held to the traditions of Mozart, while the implications of late Beethoven remained a closed book. For this reason it became crucial at the time to allow for a further development of art based on Beethoven, a direction that would take the intellectual as a point of departure, as opposed to the excess of sensuality in the prior school. You also know how Schumann carried out this task. It is significant that he initiated the period when artists undertook to represent their art through writing, that this now started to become the rule, while heretofore it had only been the exception. Schumann’s work as critic distinguished itself through his deeply penetrating artistic perspective, even though it also relied primarily upon subjective foundations and the mood of the moment was often too decisive a factor. Needless to say, such a change could not advance without some Sturm und Drang, and at times what seemed to be acceptable limits were somewhat exceeded. Schumann nevertheless deserves much credit for having brought to life the new epoch of music.

While I later made these principles of my predecessor my own, above all emphasizing the present and demanding the advancement of our age and our art, I attempted at the same time to push for greater clarity of critical perception [Auffassung], that is to say, to work out the side of objective, empirical knowledge. It became necessary to conceptualize in its inner cohesion that which up to then had appeared merely as coincidental and arbitrary, especially to comprehend the present in its inner link with the past, which was not really Schumann’s concern. It was a matter of attaining firmer principles than were possible up to that time, indeed, to attain principles at all. Musicians earlier only felt, or knew, themselves to be united through the technical side of art. In matters of aesthetic comprehension the most extreme arbitrariness prevailed, and the realm of opinion was a chaos of the greatest contradictions.

It was for this reason that now a number of years ago, I gave the first impetus for a musicians’ assembly,11 which was likewise held here in Leipzig, as you know.12 The memory of that first undertaking is fresh, now that I see you all gathered here again, and if I were to make a comparison between then and now, it would not merely be one of externals and chance. No, a glimpse at that which we attained earlier will bring us closer to comprehending our current task.

It was remarked that that gathering had only slight results. This is admittedly true, if you have in mind that which directly impacts life, immediately visible and tangible; but it is very untrue if we are willing to think about less obvious results. At that time it was a matter of giving expression to the desire of musicians for mutual convergence, of drawing art and artists out of isolation, out of a state of fragmentation into as many atoms as there are artists—in other words, of working toward a community of knowledge and of endeavor through inclusion of individuals. This was actually attained, and the ground was laid for that which developed later; the efforts of the journal were considerably advanced and supported through it.

Now those earlier developments are undergoing a reprise. In the meantime, however, conditions have significantly altered. That greater clarity of critical perception initiated, then, the maintaining of specific principles, understandably led to renewed division—this time, however, not to a chaotic disarray but rather to a conscious separation, to the formation of special groups, and ultimately to the creation of parties. The Neue Zeitschrift für Musik thereby entered into a party position, although really against its will, in a certain sense. This occurred intentionally and consciously, if you see such partisanship as the desire to maintain specific principles in opposition to a worthless chaos of opinion, such as was the norm up to that time; it occurred against the will of the journal, however, if you confuse such partisanship with exclusiveness and one-sidedness.

How the newer partisan battles have developed as a result of such a position is so well known that I only need remind you of it here in passing. An unbroken organic development does reveal itself from that time up to the present. Even before debates over the newest endeavors, I had already represented the same principles, in part, as a glance through the early volumes of the journal will show you—it was only a fulfillment of that to which I had aspired when the masters of most recent times appeared and gave practical evidence through their artistic creations. This also explains, incidentally, the close affiliation of the journal with two of these, an affiliation that is thoroughly objective, a matter of principle.13 Arriving independently from different points of departure, it was inevitable that we should come together. I admit that earlier I often doubted and asked myself whether I was not in the process of dictating to music an inappropriately heterogeneous, pluralistic agenda. The artistic activity of the latest masters has freed me from my doubts and provided me with the proof I was not mistaken.

It was in this way that the party battles of recent years originated—they have unfortunately increased to a degree that in terms of animosity they really could bring to mind the religious fanaticism from earlier centuries of our history, as one opponent recently observed.

Anxious dispositions have asked whether such partisanship is necessary for the well-being of the art, and they have lamented it from the start. I answer the question unhesitatingly in the opposing, affirmative sense, and see progress in such battle. Nothing really influential or lasting can be attained without some Sturm und Drang, without passions being spurred on, and if Schumann, in his time, had not also sometimes gone overboard in his enthusiasm, we would never have emerged from our earlier lethargy. Thus significant things have already been accomplished, in truth, and we can look back on them now as real achievements. A new epoch of heightened intellectual life has come about in the realm of music, with a rich literature of writings about music. Musicians have woken up, have been freed from immersion in their moribund, subjective emotional lives. Now almost all of them have had significant success as writers in representing their art and aims, while earlier, as mentioned, they hardly ventured to pick up the pen for the sake of making their critical views known. Through this activity, elevated interest has been stimulated in the furthest circles, also with the public. Such general engagement with the world of art puts musicians back in the position to accomplish infinitely more for their own discipline than would have otherwise been possible. Out of many potential examples one may suffice for you to infer the great difference between then and now. At the beginning of my journalistic activity I strove long and fruitlessly to promote a German translation of Ulibischeff’s Mozart book before, eventually, I succeeded in this.14 Now, every month brings more substantial works about music than once had appeared over a matter of years. It should be obvious, too, that much of this has also made possible the ambitious ventures in the realm of practical composition we now enjoy.

Certainly none of this could have been achieved without some detrimental consequences, too. I have already recalled the vehemence with which the battles have been waged. However, it is not just this vehemence we have to lament: there have also arisen boundless misunderstandings, and misrepresentations to such a degree that one hardly recognizes the original core; a prejudice has set in that does not and will not see or hear; a Babylonian confusion of tongues, amid which the different parties hardly understand each other; much unexampled animosity, even vulgarity, has become the order of the day in the field of music.

If we weigh these conditions, the question arises whether it is not high time to bring about some change, whether it is not time to hold on to our gains, to continue positive developments, and to expunge the more unfortunate ones, in a word: to take steps toward the reconciliation of the parties. Party positions are not abiding or final, but rather moments of transition—they have their significant uses, but are also likely to be discarded over time in order to make way for a mediating, more universal outlook.

I consider that this moment has arrived, a moment desired by all sensible, right-minded people. That is the cause I am presenting to you here and for which I request your participation. That is what I designate as our task, as the idea behind our festival: this is something that can be attained to a lesser degree through the press, but fully only through such an assembly. One might ask why such an assembly is needed, since the lectures are published, and time is too short for discussions that could go into more detail. The answer is the same as that given to individuals who think that university lectures are superfluous, since what is taught can already be found in a thousand books. One can agree with this straightaway, yet still decisively be of the opinion that those lectures cannot be replaced through any other means. The essence of our assembly does not consist of attaining immediately practical, palpable results in a few hours—for that we would need many days; rather, the internal stimulation, the direct observation are to be gained. A more personal approach, a personal familiarity with all of the conditions and relationships is the main thing—and it is a great deficiency of our opponents that they neglect this. Do not imagine, moreover, that I suppose I am speaking here to some assembly of dissenters with the aim of bringing them around. I know that the opposite is the case. I hope to find among you a consensus, and thus the moral force with which you are able to support such principles. An assembly of artists like the present one, consisting of men of quite differing perspectives (despite all their agreement on the main issue), must result in a more general understanding if the group is to endorse my principles, as I hope. As before, at the first of our gatherings, the further working out of that which has been established at this meeting remains a matter of the press—of [our] journal. Now it is a matter of having you disseminate within your circles the change, the progress that we hope to accomplish here, and to bear witness to your opinions.

If we are that far, if we have come to that point, it becomes necessary for me to express my opinion more precisely about how I desire such an understanding to be taken, to formulate the decisive propositions.

I do not mean an immediate amalgamation, a complete elimination of all differences of opinion, which would be an impossibility as well as an absurdity. Thus I do not intend a leveling, which rests only on the blurring and blending of differences. It also would not mean a cessation of battle where that is required by irrefutable necessity. I desire an understanding through the elimination of misunderstandings in those extraordinarily many cases where the differences really only arise from misunderstandings. I desire understanding, agreement with sensible opponents through becoming mutually clearer, through agreeing for the sake of art in all of those equally numerous cases where no differences of opinion can really exist. I desire moreover the elimination of the fully useless animosities in the press, the removal of those rude battles, even with a genuine and irremovable difference of opinion. I insist that, if argument is necessary, it be aboveboard and conducted with decency. For that purpose we sincerely extend our hand, so that the press can work itself out from the confusion of the present and make a step forward. Also, since to a certain extent we gave first initiative to action (while we are not responsible for the animosities, which are solely the work of the opposition), I think it is appropriate that steps toward conciliation should now be made from our side. However, should that not succeed, should my good word find no solid foothold, then I will consider myself sufficiently justified before you in ceasing to show that due respect we have maintained so far to those who would remain incorrigible, who close their eyes and ears to the clearest and simplest instruction, who cast about themselves armed only with prejudices pulled out of thin air, which they then lay at our own feet as if these represented our own opinion; I think, then, we will also be justified in quite freely pointing out to them how their opposition is unfounded, their argumentation mere empty chatter. We are not calling for reconciliation at any price, for understanding is only possible with those who understand. Moreover, no external coercion of any sort can determine this step for us. If need be, let the battle continue in the current manner.

If the latter, however, we do not fear. There is too large a majority of the well meaning, so that the few incorrigibles must soon be dispatched.

I. The first matter of concern in reaching an understanding is to work toward the elimination of the countless misunderstandings, simply by setting out what is true and accurate. We must recognize that many things have been and continue to be fought over to no purpose—in many cases we must realize that this has been much ado about nothing. The better informed have known this for some time, however much the opposition still misuses the situation, so that what began as honest misunderstanding continues to be exploited as a convenient tool to generate bad feeling.

To illustrate the point, let me recall in passing several examples of such drastic misunderstanding.

When Wagner appeared with his doctrine of the artwork of the future, many traditional, specialized musicians [Sonderkünstler] believed that they were to be immediately eradicated, and thus saw no more pressing need than to save their skin in the best possible way. Granted, Wagner cut a rather brusque figure, and some of what he published appeared rather hyperbolic. People did not sufficiently consider, however, that none of us fully agreed with Wagner in every detail, or that, in fact, we quickly endeavored to soften the brusqueness, to strip away the exaggerations. Time and again, nevertheless, these exaggerations were turned into the object of attacks, without subsequent mitigating efforts ever being taken into account. This has continued up to today: with this year’s first Lohengrin performance in Berlin, the local papers have yet again trotted out familiar talk, oblivious of any later developments.15 They still held on to the husk, failing to discover the great kernel of Wagner’s teaching.

Moreover, the term I coined of a “superseded viewpoint” [überwundener Standpunkt] has given occasion for conflict, evoking more of the same attacks from the broadest public circles, even those where the views and tendencies of the new direction in music have not become known.16 Misunderstandings have been the basis for this, however, and the confusion of opponents alone bears responsibility when a simple sentence is assigned an importance not intended for it. Accordingly, this type of confusion must finally cease—whoever cannot extricate himself from such confusion should just be told to learn more about the case before speaking on it. There have been exaggerations [on our part] now and then, exaggerations that seem to have granted the opponents greater justification on this count. Here as well, however, misunderstandings are the cause: the perspective of young hotheads has been mistaken for the general principles of our party. It is equally inadmissible—even in cases where mature individuals may express themselves disparagingly—to pass off subjective views as those of the school. One has to differentiate between the individual and the general. Exaggerations crop up everywhere there is life and activity, and if opponents are right to a certain extent in taking offense, they should not forget that during Mendelssohn’s time such was exactly the case here in Leipzig, and no one would think of putting the blame on him.

Were we to pursue the origins of such misunderstandings, we would indeed have to lay the blame almost exclusively at the door of the oppositional party. This group failed to notice that a major new intellectual movement was afoot, that it had developed while they slept. Suddenly awakened, our opponents are now disoriented, in too much of a hurry, having read one thing not at all, and another only partially; they are unable to access the spirit of the times. They speak like the blind would of a color, about things whose development they have not followed at all, and then fail to notice how they are struggling really only against their own misunderstandings. If our opinions were truly represented by the absurdities so frequently attributed to us from the Rhineland, for example, I would be the first to concede to our opponents.17 For this reason I must describe the necessity of the opposition to us as fundamentally pointless, unfounded and mistaken. Our principles are so embracing, and always so objectively supported, that the supposedly justifiable opposition has really nothing more to fall back on than those weaknesses that adhere to any human undertaking. Meanwhile they ignore any positive results of our efforts. This is a miserable, comfortless business; one might well suppose they pursue it merely in order to say something different, and so to preserve some form of existence. They want to maintain Classical principles, but their notion of the “Classical” resides not only in the true attributes of the idea but as much in its characteristic deficiencies. They seek to maintain these deficiencies because, simply, they have not advanced enough in insight to recognize them as such. If we agree with our opponents to a certain extent that the old days must provide the foundation and starting point of music education, they nonetheless err in defining the “Classical” too exclusively according to historical period, while neglecting undeniable good things produced in modern times. They believe it a matter of egoism and arrogant domination when we express ourselves brusquely in the interest of art and out of a sense of duty. They look for bad motives because, as a result of insufficient understanding, they cannot instinctively explain the matter to themselves. In all of this we encounter yet again—in those rarer cases, of course, where truly pure motives are decisive—the strange conceptual confusion; namely the belief that some are called to be the gatekeepers for art. Meanwhile they cannot comprehend or will not concede that we are led by a similar sense of duty: the endeavor to protect art from that stagnation and decay into which it would inevitably descend were they in fact correct.

But enough of this. It was necessary to provide several proofs, and in doing so I have not even considered the equally numerous cases where they believed they were able to press their own case best by simply opposing us. It has also occurred often enough that the others found their expectations disappointed; that they were not so represented in the journal as they would have liked to be, and as we would have gladly done were it possible—for that reason, they went off and wrote invective. Here I envision, as said earlier, the kind of understanding that is easy to achieve with good intentions, even without concessions from either side, since it is only a matter of mutual enlightenment.

As the situation now stands, I emphasize most the necessity of a personal exchange of opinions, the necessity of presenting one’s own position on the spot. At this moment many who still incline toward the opposition would be quickly convinced, if they met the conditions I have just expressed here—as, in fact, duty obliges.

At any rate we, and the journal, are also to blame, up to a point, and I would be the last one to want to hide this. I spoke openly about the faults of the opposition, and the other side of the matter should be treated no less openly. I already indicated how, before Schumann started writing music criticism, the most lamentable half-measures and cautiousness had become the norm. Schumann took the path of greater open-mindedness, and thereby restored the state of musical life to vigor and health. It was only natural, then, that I took up this legacy, extending it further in many directions, and what for Schumann had still only been accidental and subjective, I elevated to a lasting foundation. In addition, to give you just one example, Schumann had not yet dared to debate with contributors to this journal in the journal itself. I immediately introduced this practice, and now it has become customary everywhere. That proper moderation could not always be observed in this has to do with the very nature of a development that had not yet reached its conclusion. Open-minded as I like to think myself, I have not always been so particular or apprehensive as to reject those perhaps all-too-decisive pronouncements of my esteemed colleagues, and for this reason some isolated excesses have certainly occurred that would have been better avoided.18 Now, with a long and rich experience behind me, I have gained some perspective, I know exactly what I need to do, and how it must be done; thus my motto is: “Mutual understanding among all who are impartial, without of course doing damage to conviction; a more decisive stand against those who simply refuse to hear another’s viewpoint and who continue to spread suspicious rumors and untruths—even now, when a conciliatory hand has been extended toward them.

II. While we clear up misunderstandings this way, we start to approach the core of the matter, getting closer to the positive side of things, to that which forms the true focus of our endeavors. That is my second important point, and we need to grasp this with full determination. Of course, here we see a wide, immense field; I cannot go into particulars here, any more than previously, I can only establish the principle.

This is, to summarize: rationalism versus the previous naturalism; self-consciousness versus instinct; the spiritual side versus the sensual; the characteristic versus the beauty of the merely formal. In our age the foremost thing is to cultivate a thinking appreciation of art. This does not altogether exclude the instinctive side; the unconscious aspect is the abiding foundation of all artistic production. But a theoretical, aesthetic consciousness should now accompany it, purifying and clarifying it; artistic production should maintain an equilibrium between both sides, whereas before the naturalistic side was given distinctly more weight. Furthermore, the great masters of the past were by no means just thoughtless naturalists; the greater the natural forces, the unconscious side, the more elevated and powerful the intellect has shown itself, in all ages and in all epochs. But the historical progression in the development of art nevertheless consists particularly in this, that the conscious side struggles more and more to emerge, so that earlier creations, when considered from the perspective of a later stage, always seem naïve. This can be seen, to give a few examples, in the much more correct handling of the voice in vocal music, a matter of extraordinary importance; and in purely instrumental music in the elimination of conventional schemata and in the greater dependence of form on content. As concerns harmony, this was originally a matter of discovering the laws of euphony over and against a raw simplicity. Thus the many restrictions and prohibitions [of theory]. We have now come to a point, long after this has been achieved, where we can consciously place the main emphasis upon the Ideal, though of course always still selectively recognizing earlier foundations. Thus every epoch may be viewed, relatively speaking, as correct in its own way.

Another product of this principle are the practical consequences. It is our task to see that the accidental, the fragmented, the naturalistic should all make way for conditions organized accordingly; we have to work toward establishing an organization of musical life upon artistic principles that will replace what has heretofore come about more arbitrarily. Though much of this is not in our power, much depends entirely on us. Among these latter things is the issue of improving the structure of concert programs, accepting the new without doing away with the old, but in some arrangement that manifests a guiding idea, in contrast to the old, slapdash routine. Equally important is the matter of theatrical reform, the improvement of musical instruction, developing institutions of musical education—the conservatories—according to modern principles; such an extraordinary number of things might be mentioned here that simply listing them would take too long. But much more is also happening these days that is not in our power to change. There has hardly been a time when the rulers of Germany were so inclined to sponsor and fund music as they are right now. Here I have occasion to recognize gratefully our esteemed patron, that German prince, whose support has made possible the present celebration; as you know, His Majesty the King of Hanover has, moreover, donated an annual subsidy of 1,000 thalers to the Handel Society, in a similarly generous act of musical patronage. The liberality with which the Weimar Court has for a long time now provided a haven for contemporary art, helping to provide a firm footing for this so that, as in the time of Goethe and Schiller, a new ideal of art might flourish throughout all of Germany—this has long been recognized and lauded. Through the support of His Majesty the Duke of Coburg the German Handel Society has been enabled to make use of manuscripts in the private possession of the Queen of England; the collaboration of two German princes has enabled Germany to achieve for Handel what England could not. And the same is true in many other cases. Now it is up to us not to remain behind, but to step forward with mature, practical suggestions worthy of such a generous promotion of art.

III. Granting all this, as I believe anyone must do, the question may then be posed whether the works themselves, those in which we see our principles realized, are really in accordance with the values and suited to serve as practical proofs of these principles. We can agree on the recognition of the fundamental principles and still harbor doubts regarding their concrete application. Even less than on previous points can I afford to elaborate on this question. Everything we have committed to print in recent years has some bearing on this, and we could point to all that by way of answers. Right now the most important thing for us is the following: the difference in opinions about [new] works has its cause primarily in their still deficient familiarity, in the lack of opportunity to make their acquaintance in performance. I have chosen the works to be performed here with this in mind.19 Many can only be judged, as is right and natural, by being heard. Thus was created this opportunity; thus was performance enabled to take the place of argument and rhetoric. That is indeed all we ask for with regard to new works, and insofar as I bring it up, I have another opportunity to set right an absurd distortion. It is our quite harmless wish that room be made for contemporary works, without in any way detracting from the works of the past; indeed we have no intention of shunning these older works. So at the moment there is no talk of battle. Only when others deprive us of light and air, refuting our fully justified demands, will the flames of battle be kindled, and then it should hardly be wondered at if, in the face of persistent opposition, restraint should finally no longer prevail.

IV. Having come this far, we need then to remove anything else that recalls the old quarrels. This is a fourth point I would like to set before you.

In this respect what might seem at first a minor matter is of some importance: the name “Zukunftsmusik.” In itself this name might appear rather neutral, but it assumes importance by virtue of its having been made a party slogan. I would therefore like to suggest doing away with this name, and offer a step toward doing so. You already know that the words in themselves are nonsensical, as I have already explained in the journal. Wagner has called the union of the arts the “artwork of the future.” By this he means a synthesis of the arts, in which each one loses some of its independence to be absorbed into the whole. Accordingly, each separate art in this sense becomes no longer self-sufficient. Therefore by speaking of “Zukunftsmusik” we single out one art—music—as a separate art, in contradiction to the whole initial intent. “Zukunftsmusik” is at one and the same time a music that is dependent and independent, something at once music and not music—a contradictio in adjecto. Of course, we cannot make any authoritative pronouncement about setting new standards right now, and so we must wait and see whether our suggestion will be accepted. But we can agree among ourselves to avoid this designation in the future, and through our example perhaps inspire others to follow; if this happens, I truly believe that the wishes I have outlined here may soon be attained.

What I have just said encompasses only half of my proposal. The other side is to employ a new phrase in place of the one to be discarded; and that is certainly the more difficult task. At any rate, the question might well arise whether any of this is necessary at all; at first glance, opinions might differ on this. Upon closer inspection, nevertheless, you will find that some new designation cannot be avoided, if not for the sake of musical practice then at least for the sake of writing about it—which is becoming more and more significant.

Therefore I will allow myself to propose a new name for you to consider and, if it meets with your approval, to adopt. My proposal is the designation “New German School” (neudeutsche Schule or neue deutsche Schule). If this new name surprises you, given that the said “school” includes two non-German masters, then allow me a few comments toward mitigating the alienating effect.20 The correctness of my suggested name needs no proof as regards at least one member of the triumvirate representing the “music of the future”: Richard Wagner. He was the first one who gloriously realized the ideal of a purely German opera, following the example of Beethoven, Weber, and a few others, and in contrast to the Italian-French-German direction represented by Gluck, Mozart, et al. The matter becomes more difficult, though, when we try to include two other, non-German masters under this rubric. Of course, it has long been recognized that these two took their point of departure from Beethoven, and thus they are fundamentally German in their roots. But both of them also exhibit undeniably foreign elements, such as might at first seem to call into question the aptness of my designation; the one betrays the intellectual-reasoning aspect of the French; the other one betrays a characteristic southern fire, the flaring up of passion, the glow and the ardor of the South, all in contrast to the unadorned inwardness and stark, compact power of the German. Burdened as they are with such qualities, the question might well be put whether both masters are to be regarded as German artists—the decisive matter here.

In my “History of Music” I have proven how two developmental paths coexist in Germany, one specifically German and one universal, the latter based on an amalgamation of German, Italian, and French styles. On the one hand we have Seb. Bach, Beethoven, et al.; on the other we have Handel, Gluck, Mozart et al. In our poetry we have the very same phenomenon: beside the specifically German of the Romantic school in Tieck, Kleist, etc. there stand the universal artistic creations of Goethe and Schiller, or Wieland’s affinity for the French character next to the purely German tendency of Klopstock. Of these artists who occupy a universal standpoint, all possess foreign elements in abundance: Greek in Schiller and Goethe, the latter embracing oriental influences as well; yet no one would think of calling them non-German. On the contrary, the nation has recognized itself glorified in them, with the result that we do not narrowly limit the truly “national” to the specifically German; the decisive thing is the authentically Germanic foundation, regardless of whether that which is built upon it is primarily German or more universal. This universal disposition of the nation has the result, on the other hand, that highly talented foreigners who reach out beyond the boundaries of their nationality have attached themselves to us—these have sought and found a spiritual homeland in Germany. Cherubini, Spontini, Méhul, and many others belong to this category, just to mention musical figures. Of course, all of them retain foreign elements. Yet no one doubts that their spiritual center is really to be found in Germany—we have no misgivings about imparting them citizenship. This applies above all to Cherubini, who has become what he is thanks to Germany and whom we consider a German master. The birthplace cannot be decisive in matters of the mind, no more than exact chronology in other cases; for it often occurs that someone living and working in one era can really better be assigned, spiritually, to an earlier style, and vice versa. In this sense, the case at hand is fully analogous. Neither artist would have become what he is if at an early point he had not been nourished and strengthened by the German spirit. As a result, Germany eventually had to become the locus of their career, and in this sense I have recommended the designation New German School for the entire post-Beethovenian development. Through this we gain both clarity of arrangement and a simpler, more consistent nomenclature. Protestant sacred music up to and including Bach and Handel has already long borne the name altdeutsche Schule (Old German School). The Italian-influenced epoch of the Viennese masters is the age of Classicism, the perfectly balanced interpenetration of the ideal and the real. Beethoven extends his hand to the specifically Germanic North and so establishes the New German School.

Of course, I cannot exhaust my theme with these remarks, having only just touched on the main point. Perhaps, however, one of the honored participants here will soon undertake a further development of this theme.

My reflections are near an end. There remains only one topic that I would like to mention on this occasion, as briefly as possible, since I believe it may be more effectively treated here than elsewhere. It is the tone that has become customary in the musical press, the manner in which artists and artistic creations are handled. I must confess that I deeply lament this widespread lack of consideration, and I would urge all of the participants here to help bring an end to it. Any opinion deserves a modicum of respect if it rests in conviction and is open to proof; we grant it the right to exist just as we demand the same of ourselves, with the qualification, of course, that in the process some struggle is not to be ruled out. However, it is time for an end to the arrogance of thinking that one alone is right, and of making reckless pronouncements in a tone of infallibility—all artists must work as a solid majority toward this end. After such abundant advances in the arts and sciences as we have seen, it is great folly to believe that one single person can in and of himself bring about that which belongs to all of humanity; to think, that is, that one’s own individuality is so all-encompassing as to contain within it every other individual. Admittedly, everyone tends to believe that his opinion is the only true, all-inclusive one, for without such an attitude it is impossible to achieve a complete honesty of conviction. Still, in our age each person should also be aware that there exist insights external to himself, which his own individuality will prevent him from ever truly assimilating. It is a matter of uniting firmness and determination with modesty, the certainty of truth with the self-restraint that is the source of true humanity, the result of all-embracing intelligence. Our philosophers once believed that each of them alone had solved the mystery of the world. Now we know that each person has at best contributed just one stone to the grand edifice of humanity: a teaching of the greatest importance for all of us.

With that I reach the end. I believe I have presented you with a picture of what we all have to strive for, and I hope that my words have been such as to find general agreement among you.

Thus I wish that this meeting may constitute a turning point, and at the same time fix the beginning of a historically significant stage.

The main thing is that we, who profess these principles, act on the basis of this collective awareness, maintaining our differences of opinion where this must be so, but in doing so not lose sight of the total picture. Musicians must stand together and represent their art, whichever party they may choose to belong to. They must recognize that reckless enmity will only serve to shake the foundations on which they stand. The opposition itself will suffer when they resist the cause of progress: without acknowledging our principles they cannot practically advance even in their own sphere. Moreover, the efforts of the opposition are rooted in the foundations we ourselves laid down, and only enabled by conditions we ourselves have worked for.

It was my wish that our assembly would be perceived in this sense. If the immediately evident results are modest, as must be the case, we may still cherish the hope that the further consequences will turn out to be all the more significant. If we should succeed in achieving this goal, the present moment will have been for us uplifting, inspiring, and these days will remain for me and for all of you who share my feelings one of our fondest memories.

1. Assemblies took place in 1847, 1848, and 1849, the latter two truncated because of the revolutionary events of those years.

2. The first to promote the music of Wagner in the Neue Zeitschrift was the Dresden musician and critic Theodor Uhlig (1822-53), in 1850; Franz Brendel himself openly advocated the progressive movement beginning with his New Year’s article of 1852, “Zum neuen Jahr,” Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 36 (1852): 1-4. Above and beyond these numerous contributions to the Neue Zeitschrift (see the complete listing in Peter Ramroth, Robert Schumann und Richard Wagner im geschichtsphilosophischen Urteil von Franz Brendel [Bern, 1991]), Brendel also promoted Wagner and Liszt in his monograph Geschichte der Musik in Italien, Deutschland und Frankreich (Leipzig, 1852, with four later editions through 1867) and the journal Anregungen für Kunst, Leben und Wissenschaft (1856-61), devoted even more exclusively than the Neue Zeitschrift to the “New German” cause.

3. The dismissive evaluation can be found in Piero Weiss and Richard Taruskin, Music in the Western World (New York, 1984), 384; for attempts to support aesthetic systems through Brendel’s article, see, for example, Detlef Altenburg, “Die Neudeutsche Schule—eine Fiktion der Musikgeschichtsschreibung?” in Liszt und die Neudeutsche Schule, ed. Detlef Altenburg (Laaber, 2006), 9-22; and Rainer Kleinertz, “Zum Begriff ‘Neudeutsche Schule,’” ibid., 23-31.

4. The “manifesto” appeared on 6 May 1860 in Berliner Musik-Zeitung Echo and was signed by Brahms, Joseph Joachim, Julius Otto Grimm, and Bernhard Scholz. However, the New Germans somehow came into possession of a pre-publication copy of the manifesto, publishing a parody of it in the Neue Zeitschrift on 4 May. David Brodbeck reprints and translates both documents in “Brahms and the New German School,” in Brahms and His World, ed. Walter Frisch and Kevin Karnes (Princeton, 1990; rev. ed. 2009), 111-12.

5. The text reproduced below is Brendel’s address as printed in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 50/24 (10 June 1859): 265-73.

6. Indeed, Schumann figures more prominently in “Advancing an Understanding” than either Wagner or Liszt.

7. “Die bekanntlich jetzt den Namen der neudeutschen angenommen hat, aus keinem anderen Grunde, als um gehässige Erinnerungen, die an das abgeschmackte Wort ‘Zukunftsmusik’ sich knüpfen, zu beseitigen.” Franz Brendel, Geschichte der Musik, 3rd ed. (Leipzig, 1860), 612.

8. The one other post-1859 edition of Brendel’s Geschichte that appeared during his lifetime (1867) reprints the same sentence about terminology, with no further use of the designation neudeutsche Schule. The 1861 address can be found in Franz Brendel, “Zur Eröffnung der zweiten Tonkünstler-Versammlung zu Weimar am 5. August 1861,” Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 55 (1861): 61-64.

9. Specific published examples by the “progressives” include August Wilhelm Ambros, Culturhistorische Bilder aus dem Musikleben der Gegenwart (Leipzig, 1860); and Louis Köhler, Die neue Richtung in der Musik (Leipzig, 1864). For the twentieth-century perspective, see Hugo Riemann’s Geschichte der Musik seit Beethoven (1800—1900) (Stuttgart and Berlin, 1901).

10. Brendel is referring to the political unrest resulting from the Austro-Sardinian War, or Second Italian War of Independence of 1859, which pitted Austria against France and Piedmont-Sardinia. At the time of the festival, the initial clash at Montebello had just taken place (May 20).

11. In the original published version of Brendel’s address this italicized phrase and others we have italicized here were given in Sperrschrift, the German practice of spacing out letters for special emphasis. Brendel also used Sperrschrift for almost all instances of composers’ names, a convention we have not followed in this translation.

12. The first Tonkünstler-Versammlung took place in Leipzig in mid-August 1847, and represented the first attempt to gather German musicians for the purpose of having a dialogue about the current state music.

13. The “two” masters alluded to here are, of course, Wagner and Liszt.

14. Russian author Aleksandr Dmitryevich Ulïbïshev (Ulybyshev, Oulibicheff, Ulibischeff; 1794-1858) published his life and works study of Mozart in French, as Nouvelle biographie de Mozart, suivie d’un aperçu sur l’histoire générale de la musique et de l’analyse des principales oeuvres de Mozart (Moscow, 1843); the German translation mentioned appeared as Alexander Ulibischeff, Mozarts Leben, nebst einer Uebersicht der allgemeinen Geschichte der Musik und einer Analyse der Hauptwerke Mozarts (Stuttgart, 1847). Brendel perhaps mentions this particular title as an instance of his intent to mediate between parties: on the one hand, Ulïbïshev’s Mozart book subjects the composer’s oeuvre to numerous Romantic literary-critical exegeses, though on the other hand Ulïbïshev went on to become an outspoken critic of “modern” tendencies in his subsequent Beethoven study, Beethoven, ses critiques et ses glossateurs (Leipzig, 1857).

15. The first Berlin production of Lohengrin took place at the Königliches Opernhaus (Royal Opera House) on January 23, 1859. The Viennese production a year earlier (opening August 19, 1858) had been an important milestone in the reception of the work, as one of the first performances in a major urban center and featuring a strong cast and orchestra.

16. Brendel had been repeatedly taken to task for his references to a “superseded” or “obsolete standpoint,” being that of conservatives who used the Viennese Classical style as a point of reference in aesthetic debates. He was accused by the “opposition” of dismissing thereby the whole classical canon as no longer valid. This term (überwundener Standpunkt) arose in the late 1830s within the Hegelian sphere of influence, to which Brendel belonged. In the writings of German progressive thinkers of the 1840s (for example, David Friedrich Strauss), it became an expression of disdain for conservative positions in philosophy and the arts.

17. Brendel alludes, presumably, to the Cologne-based critic Ludwig Bischoff and the journal he edited (from 1853 to 1867), the Niederrheinische Musik-Zeitung. Bischoff and his journal played a major role in disseminating the term “Zukunftsmusik” as a skeptical and pejorative designation for the modern school of Liszt and Wagner. It was Bischoff, incidentally, who published the German translation of Ulïbïshev’s Beethoven study (see note 13) in 1859, with its provocative criticism of the late period and, by implication, of the modern school that claimed to be the inheritors of that style and to have realized the implications for the “future.”

18. One example Brendel might have had in mind here was the publication of Wagner’s essay “Das Judentum in der Musik” (“Judaism in Music”) in the Neue Zeitschrift in September 1850. Since the article was published under what was understood to be a pseudonym (K. Freigedank), Brendel had to assume even more responsibility for the piece, as editor.

19. The opening concert of the Tonkünstler-Versammlung, conducted by Franz Liszt, included Liszt’s symphonic poem Tasso and the Prelude to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, only the second time the Prelude had been heard in public (Hans von Bülow conducted the first performance in Prague on March 12, 1859; both the Prague and Leipzig performances used the concert ending Bülow had composed for it). To honor the Neue Zeitschrift founder Robert Schumann, his opera Genoveva had been performed the day before the Assembly (May 31). On June 2, Liszt conducted his Gran Festival Mass in St. Thomas Church, where Carl Riedel then directed a performance of Bach’s B-Minor Mass on June 3. Subsequent concerts included Schubert’s B-flat Piano Trio (with violinist Ferdinand David, cellist Friedrich Grützmacher, and Bülow), and an organ recital in the Merseburg cathedral. See Alan Walker, Franz Liszt (New York, 1989), 2:511-13. The New German critic Richard Pohl published an extended account of the Assembly and concerts as a brochure, Die Tonkünstler-Versammlung zu Leipzig, am 1. bis 4. Juni 1859 (Leipzig, 1859). See the printed program for the inaugural concert of June 1, 1859 reproduced as Figure 1.

20. Brendel assumes his audience’s familiarity with the linking of the names Berlioz, Liszt, and Wagner as the principal representatives of “modern tendencies” in the 1850s. The fact that neither the names of Berlioz or Liszt are actually mentioned in the address (nor any work by them) suggests that Brendel felt some compunction about the term he coins here, hence also his attempt to defend it in this passage.