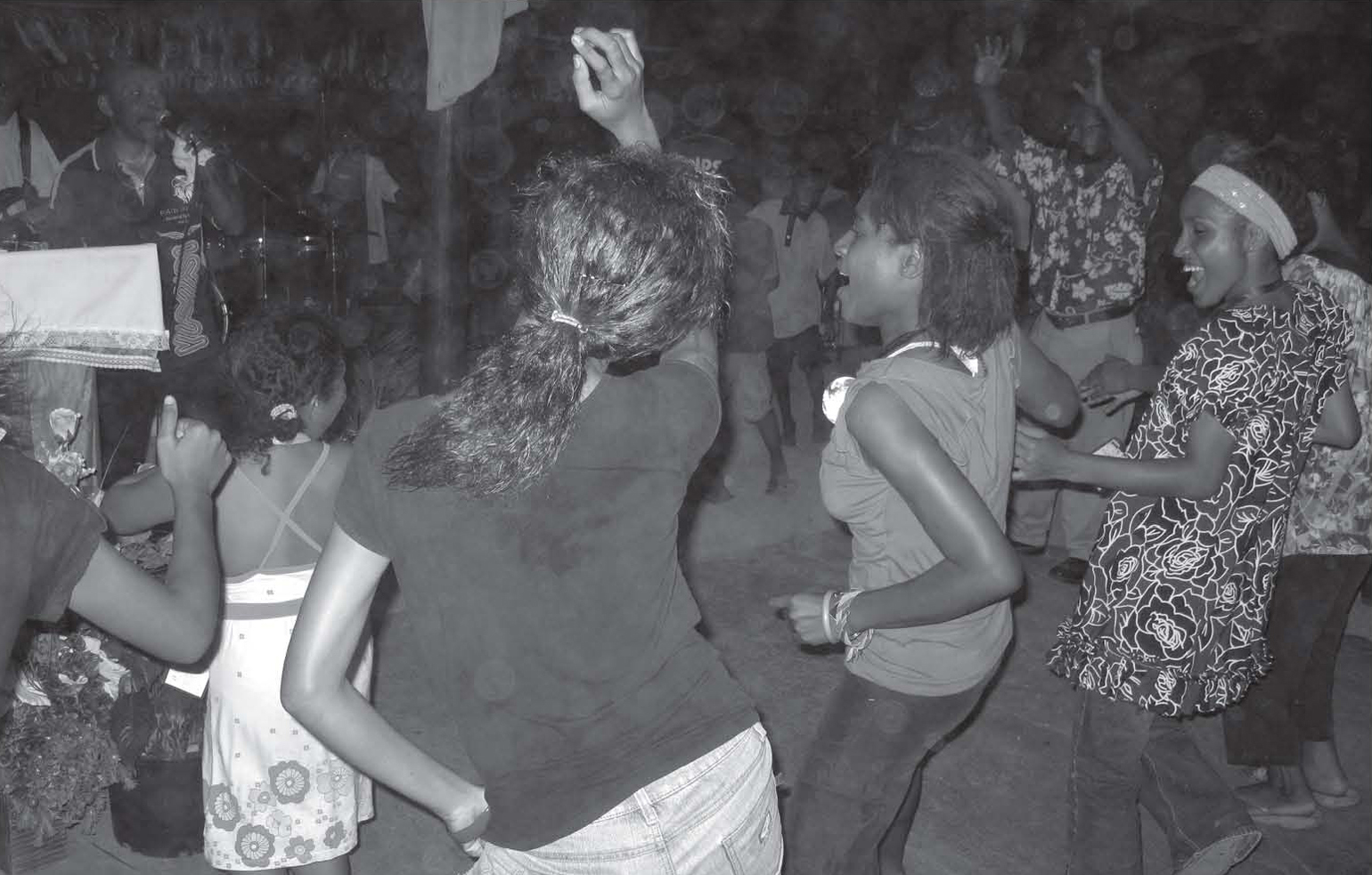

In Port Moresby in April 2010, while undertaking research on Christian musical expressions in Papua New Guinea (hereafter PNG),1 I was invited one midweek evening to the training center of Covenant Ministries International, an isolated, open-walled venue at Eight Mile, on the city outskirts, to attend an event billed as Breakthrough Praise. Here, I was told with pride, I would experience “high praise.” As I was to learn, this is a local term for an extended form of song-based Christian worship involving shouting, cheering, speaking in tongues, jumping, and club-style dancing by teenage girls (fig. 4.1). The entire two-hour-long song sequence—which followed forty minutes of microphone-led and often-hectic prayer and tongues—was sung in English and set in the same key. An expert gospel rock band was absorbed in shaping and responding to the mood; its musicians spontaneously wove contrapuntal lines into and around the sound stream, while punctuating it with rhythmic accents and cymbal splashes. Around eighty people of all ages and from at least several PNG ethnic groups were in attendance, and from the start their singing was a harmonious cloud of contained exuberance. It began with the gently rocking sounds of the locally composed theology-laden worship classic “Abounding Grace”:

Fig. 4.1 “High praise” freestyle dancing at the SOS Breakthrough Praise night in Port Moresby, April 2010. Pastor Daniel Meakoro is on the microphone in the top left-hand corner. Photo by the author.

We are born because we’re called

We are running because we’re chosen

We are serving for we were ordained

Living our lives predestined by grace, amazing grace

Until we see the coming of our King.

Amazing grace open my eyes

Abounding grace unveiling your ways

Till your glory manifests in us

Men on earth will see your face.2

Over the song’s eight-minute rendition, backing vocalists offered improvised solo interjections and responses, and the worship leader and song’s co-composer, Pastor Daniel Meakoro, flanked by fellow pastors Oswald Tamanabae and Peter Bogembo, measured out tuneful exhortations: “Jesus, we worship you! Jump into the river—jump into the river of worship! Send a proclamation across this nation!”

Breakthrough Praise was part of a weeklong series of workshops entitled SOS, or School of Strategies, culminating in a public outdoor Praise Extravaganza, all conceived to equip participants with skills in media technology useful in Christian outreach. Here, it appeared, was a gathering of local Pentecostal Christians rehearsing their liturgy (and evangelism “strategies”) in accordance with their understanding of transnational models and methods. The SOS was organized and run by Bogembo, Meakoro, and Tamanabae, a trio of PNG’s veteran elite musicians, all Pentecostal pastors who had been pioneers in popularizing local gospel and worship music. Those in attendance were drawn from small Port Moresby Pentecostal “fellowships” affiliated with Covenant Ministries International, including those established and led by Pastors Meakoro and Tamanabae—Brook by the Wayside and House of Bread, respectively.3

Given the technical and stylistic versatility of the musicians, the extensive use of English-language global praise “hits,” and the incorporation of freestyle disco dancing, “high praise” appeared to be a sophisticated urban variant of the Pentecostal (and Pentecostal-like) worship4 I had previously encountered on the north side of PNG.5 This liturgical form or set of practices, which I refer to more generally as Pentecostal-charismatic worship (hereafter P-CW), is a postmissionary-era phenomenon in PNG that has become widespread and influential over the past several decades.6 Anthropologist Courtney Handman, for example, recently noted a “Pentecostal norm” of worship conventions becoming ever more common in the country (2010, 231n3).

Significantly, in a nation renowned for radical linguistic and cultural diversity, as well as a fragmented religious landscape resulting from a variegated history of evangelization, P-CW practices began forming in the mid-1970s, during the immediate post-independence era, and have become a widely shared indigenous form of participatory music making.7 In this chapter, I consider P-CW practices as representing a transformational shift within the urban and rural musical culture of PNG. First, I employ various sources, including my own fieldwork, to construct an overview of manifestations of the new liturgical form.8 Then, by way of a case study of the three organizers of the SOS, gospel musicians whom I refer to as the Oro “brothers” after their province of origin, I explore the Pentecostal revival–inspired transmission of instruments and song repertory between villages and urban centers, which led to the founding of P-CW.9 These three “brothers”—and a fourth, Tony Ando—were important as brokers of both commercial gospel and grassroots-level worship music.10 Finally, I discuss ways in which their music is imbued with what I term a “spatiotemporal millennialist aesthetic”—that is, how, in terms of musical form and style, they believe that their songs and “high praise” or P-CW performance prepare individuals and the PNG nation, as part of the Christian transnation, for God’s future blessing.

P-CW is a liturgical form that in PNG involves “ecstatic singing and dancing, vigorous backchannels of ‘amen’ and ‘hallelujah,’ lots of hand clapping and hand raising, and group prayers” (Handman 2010, 230). Two broad types of P-CW are practiced in the country—one at church services, the other at crusades (table 4.1). Each is shaped according to its key purpose, which, in the case of the former, is worship, broadly construed, while the latter is dedicated to public witness and outreach. In worship services, the P-CW segment is prefaced with an extended time of prayer, led by a specially designated individual from a microphone, which builds in fervency as the congregation joins in—a practice known as bung beten (Tok Pisin [TP], collective prayer). The prayer time is generally shortened for crusades and tends not to involve the audience in bung beten, and the person praying is also the worship leader. Preaching follows in both forms, and healing and (or) an “altar call” involving confession of sin and (or) a decision to follow Christ bring the event to a close.

TABLE 4.1 Comparison of the place of Pentecostal-charismatic worship (singing, dancing, and praying with instrument backing) in generalized crusade and church service. The crusade format is more fixed; in the church service format, announcements, offertory, and perhaps other short segments are inserted at various points.

Crusade (ca. 2 hr., 30 min.) |

|||||

Solo-led prayer, with instrument backing 10–15 min. |

Singing and dancing 30–40 min. |

Preaching 40 min. |

Healing / altar call, with instrument backing 30–40 min. |

Closing song 5–10 min. |

|

Church service (ca. 2 hr., 30 min.) |

|||||

Ecstatic prayer or bung beten, with instrument backing 15–25 min. |

Singing and dancing 30–50 min. |

Preaching 40–50 min. |

Transition: solo song or instrumental music 5 min. |

Altar call, with instrument backing 10–15 min. OR Testimony time (no instruments) 25 min. |

Closing song 5–10 min. |

The church service version of P-CW tends to involve committed congregants intensely focused in purpose; hence, as already mentioned, the attendant atmosphere can be fervent. Services are usually held in a structurally open building of the kind designed for public meetings in a tropical climate. Since these are partially or completely open sided, the sound of worship spills out into the environment, itself a form of witness (see Farhadian 2007).

“Crusade,” Handman notes, is a “local term roughly equivalent to a tent revival” (2010, 239n9). All over PNG, Pentecostal groups constantly mount crusades, outdoors and mostly at night, erecting stages in public parks and open areas in cities, towns, and villages.11 Since crusade P-CW invites wide and often spontaneous communal participation, the event can become a kind of all-purpose public celebration. Those who attend are often affiliated with other denominations or church groups. Children, youth, and women, in particular, join in by singing, jumping, and waving palm fronds or branches of cordyline plants.12

P-CW is led by at least one singer on a microphone and ideally is driven and accompanied by a fulset (PNG English, full set)—that is, a rock band setup with some combination of acoustic guitar with pickup, electric rhythm / lead guitar, bass guitar, keyboard, and drum kit—as well as guitar amplifiers, a multichannel mixer, and public address system. Spoken exhortations of encouragement to congregants by the worship leader are an important feature of P-CW. These are intermingled with snatches of prayer asking the Holy Spirit to descend and bless not only the local place and people gathered but also the wider sphere and often the whole nation.13

For P-CW leaders, dress in the colors of the national flag—red, black, gold, and white—is fast becoming the standard formal attire at crusades and Pentecostal churches in urban centers. Women leaders wear a long home-sewn version of the meri blaus (TP, women’s blouse, a long loose-fitting dress introduced by missionaries) and men a polo shirt in these colors. In a YouTube video of a recent “Holy Spirit Crusade” held at Kimbe in West New Britain Province, men and women, locals and visiting guests, are seen wearing the national colors (see “Kimbe Holy Spirit Crusade” 2012, from 1:06), and the various indoor and outdoor venues are extensively decorated with red, black, and gold bunting. Wearing the national colors is an indication that Pentecostals in PNG identify as a community at the national rather than primarily the local level, as well as an index of “participation in the Christian transnation” (Robbins 2004, 176).

P-CW songs are either very local in origin or from around the country or overseas. They are sung in indigenous languages, Tok Pisin, and English, depending on geographical location and context. Songs are sequenced so as to progressively build emotional intensity. Angela Panap, a Pentecostal worship leader with the Joseph Kingal Miracle Centre in Lae, explains that P-CW songs are ordered with the aim of taking participants to wanpela kain poin, na level, na mak (TP, a particular point, and level, and mark). When this mark is attained, “everyone is so alert to receive the Word. But if we don’t hit that mark in praise and in worship you’ll see the people are tired” (October 7, 2008). In an effort to reach an emotional high point, crusade P-CW sometimes threatens to descend into disorder, and I have witnessed a pastor sternly warning a crowd to cool down after the music team has worked single-mindedly to foster exuberance.

P-CW involves various kinds of dance. During the 1998 Assemblies of God Jubilee celebrations at Maprik in northwestern PNG, many of those in attendance at the outdoor daytime event waved palm branches as they moved counterclockwise in a large circle, while singing to fulset-accompanied songs such as the early praise “hit” “Holi Spirit kukim” (TP, Holy Spirit burning) (see “Revival Celebrations” 2012). This crusade-type gathering took on the general appearance of a singsing (TP, traditional dance festival). Crusade P-CW dancing I observed in Lae in 2008 was less organized, with participants jumping up and down in a crowd-like mass in front of the stage platform, waving palm branches. The aforementioned “Holy Spirit Crusade” at Kimbe in 2012 featured a formal opening ceremony that included dancing by a group of women dressed in the colors of the national flag, over which some wore bilas (TP, from the English “flash,” meaning dance accoutrements, decorations). They performed two distinctively traditional-style dances to fulset-accompanied singing. The first was a welcome procession with dance movements; the second involved around thirty women and traditional-style choreography (“Kimbe Holy Spirit Crusade” 2012, 1:06–2:18). In contrast, dancing in church service P-CW tends to be more contained but also more individualistic, although it can be exuberant, as was the case at the SOS Breakthrough Praise event (see fig. 4.1).

A general mood of optimism surrounded the 1975 declaration of political independence in PNG. Independence in the political sphere to some extent coincided with a handover of the nation’s churches to indigenous leaders. All over the country, people composed and sang songs of unity, in both tok ples (TP, local indigenous language) and Tok Pisin, and the subsequent, related rise of a national music industry stimulated a great interest in mastery of the rock band as an ensemble. Probably not coincidentally, around this time intense Christian revival activity broke out in various parts of the country. Anthropologist Joel Robbins suggests that this was an era of Melanesian “great awakening,” as communities were “swept by waves of healing, prophecy, visions, tongue speaking, and other ecstatic phenomena” interpreted locally as “outpourings of the gifts of the Holy Spirit” (2004, 122). Indigenous theologian and musician Andrew Midian interpreted the revival as “the young people’s cry for religious independence” (1999, 47).

“Instruments create consequences everywhere,” ethnomusicologist Mark Slobin observes, and this was certainly the case surrounding the 1970s PNG revivals (2010, 17). Through the revival, the guitar became pivotal to the foundation of P-CW in two ways (see Strathern and Ahrens 1986, 20). First, it sparked the creation of the kores (TP, chorus)—that is, indigenous praise and worship songs (Midian 1999, xxxiii–xxxiv). This explosion of local songs was largely a rural phenomenon. Second, with the drum kit and later the keyboard, the guitar was central to fulset worship taking hold in the PNG church. These instrumental skills were largely disseminated from the cities of Port Moresby, Lae, and Rabaul.

In 2012–13, the PNG P-CW musician Robin Kawaipa teamed up with the Australian-based transnational Pentecostal church Hillsong under the name OneBell to produce a polished album of praise and worship songs sung in Tok Pisin, entitled Kisim i go.14 This collaboration resulted from Kawaipa’s study at Hillsong College in Sydney.15 While one might be inclined to assume that such global musical connections are relatively recent, in reality they date back some thirty years, as the case of the Oro musicians makes clear.

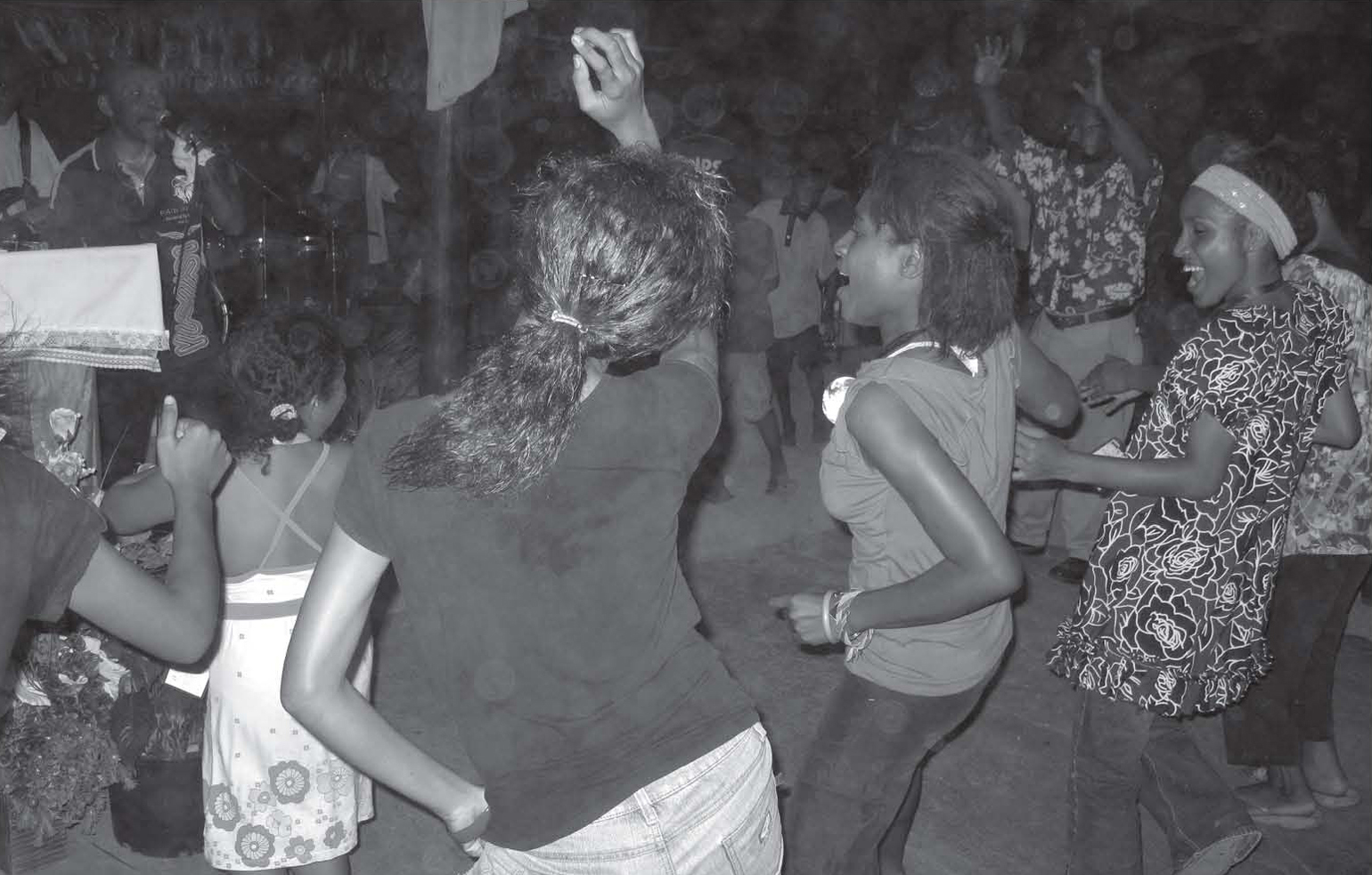

The Oro “brothers” (fig. 4.2)—Peter Bogembo (b. 1968), Daniel Meakoro (b. 1966), and Oswald Tamanabae (b. 1965)—were peers with a background in the Anglican Church whose families originated from different villages within the Binandere language area of Oro (Northern) Province.16 The revival that broke out in their province was spearheaded by an Australian Pentecostal organization called the Christian Revival Crusade (CRC), which had established the Bethel Centre as its base in Port Moresby in 1972 (Gallagher 2011, 197–99). As Gallagher reports, Oswald’s parents (Grace and Thomas) were instrumental in persuading other members of their family to become committed members of the Bethel Centre congregation. It was through members of the Tamanabae family worshipping there that in 1976 “revival ignited and spread like fire across Oro Province” after some of them returned to evangelize villages in their home district of Ioma (202). This revival had a profound impact throughout Binandere and later other villages, including on members of Bogembo’s and Meakoro’s family, resulting in what Robbins terms “second-stage conversion.”17

Fig. 4.2 The Oro brothers (and mentor) at Boroko, April 2010. Left to right: Oswald Tamanabae, Daniel Meakoro, mentor Iara Eliakim, Peter Bogembo. Photo by the author.

As youths during the time of the revival, the brothers were excited by musical changes in the wind. Bogembo recalls, “Before we were used to hearing hymns, and suddenly they’re singing songs like [Hank Williams’s] ‘I Saw the Light’ and [the “country-fied” hymn] ‘At the Cross.’ When they put music into [added instruments to] those type of songs—they had a bit of rhythm—it became totally new, a new sound! And it caught the attention of all the young ones, especially the younger generation” (April 20, 2010). Gallagher explains that such English songs, used by CRC team members in their “missionary outreach patrols,”18 gave way to songs of praise and worship in indigenous languages (2011, 276–77). Until the revival, “language songs” had been considered the domain of the secular, guitar-based string band idiom, but at that time it occurred to youth that the string band could be adapted to Christian ends. According to Richmond Tamanabae, Oswald’s uncle, as a result of the revival, “language songs became very, very popular and powerful” (quoted on 277). Digby Ho Leong, a close friend and musical associate of the Oro brothers, explains that revival-prompted, Spirit-inspired song composition became the norm in villages around the country: “Every so many years revival breaks in and then everybody is renewed.... It starts in one place and spreads throughout the nation.... When everybody catches on, that’s where all the new songs come in, because everybody gets different impartations and different revelations, and they write about them.... They just sing about them and express what they feel inside” (January 15, 2008). Midian, an ordained minister of the United Church who was deeply moved through his encounters with a Pentecostal revival in northeastern New Britain in the 1980s, confirms this, noting that “many young indigenous Christians are writing gospel songs... indigenous in sound... [which] have gained popularity with Christians throughout the nation” (1999, xxxi).

Meakoro recalls that while the brothers were involved in this string band changeover, they always had an ear open for what they considered more dynamic sounds: “We were enjoying the local19 and watching the trends—country music and rock music that was playing on the radio. They [that is, country and rock] were a lot more appealing.” He continued, “We wanted the beat, we wanted the drums.... And then, this revival was coming and we couldn’t sing hymns, because we needed something that was more upbeat, more up tempo, that could gain a bit of rhythm... that people could dance with and jump with—or, you know, flow with” (October 18, 2012).

Moving around between their home province and the cities of Lae and Port Moresby during their later teens, they discovered that laiv ben (TP, live band) or amplified gospel country rock was beginning to be used in several churches in the cities. “We were trying to pattern after” two groups in particular, explained Meakoro: a “country”-style Christian band called the Jesus Experience based at the Foursquare Gospel Church in Lae, where Meakoro undertook some of his secondary schooling, and the Bethel Singers, a band formed at the CRC’s Bethel Centre at Tokarara in Port Moresby, where Oswald Tamanabae began as a drummer. These groups were among the first church worship bands in PNG comprising local musicians. The sounds and idea of Christian popular music “just rubbed on us as we were growing,” Tamanabae remembers. “The first time I heard the Jesus Experience [on cassette],” Bogembo concurs, “it was like, ‘Wow! Christians can sing like this?’ I said, ‘So Christian music does sound like this too?’ It was a new [concept]!” (April 20, 2010).

Meakoro refers to himself and Tamanabae as “dropouts” (October 18, 2012) and explains that at first the brothers had no clear direction, only an urge to be creative. Despite feeling that they were church “captives” due to their families’ deep involvement, it was the eventual personal “discovery” of God that brought purpose to their innovation: “At the early stage we were captured with the church, the Faith, and everything in there. Because this passion was strong and we were creating, you know, we were actually really initiating a new trend.... Then we discovered God for ourselves, and I think that’s where the trend of music—the trends and the desires, the passion, and even the worship aspect of it started taking another trend. But the creative aspect of it continued, you know” (April 20, 2010).

Meakoro and Tamanabae were encouraged to gain proficiency on rock band instruments by “our big fathers” (October 18, 2012), Richmond Tamanabae and Pastor Peter Igarobae, respected family elders who served as their spiritual guardians. Motivated to make a musical impact on their own local area in those early years, they remember being stretched for resources:

MEAKORO: We didn’t lose our passion for music—we were developing that, really literally from scratch. We didn’t have amps, so we have stories that we laugh about.

BOGEMBO: We were using loud-hailers to amplify the guitars...

MEAKORO: We had to hang cymbals on a kind of clothesline...

BOGEMBO: And on one trip up to Kokoda, we didn’t have a mic stand, so we had to put a forked stick in [the ground] and hang the mic down...

TAMANABAE: And wherever the wind blew we had to follow. [laughter]

(April 20, 2010)

Such were the challenges involved in establishing “live band” or fulset worship in the remote, rural areas of PNG.

Understanding this era as their “season” collectively (discussed further below), in retrospect the brothers see themselves as agents of a spiritual change—or, as Bogembo put it, an “awakening”—that was “breaking out” at the time:

MEAKORO: Every creative aspect, it was breaking out, if you like! The trend of [break] dancing, the trend of music, anything to do with performing arts, we were tapping into that.

BOGEMBO: We could even write scripts of drama—dramatizing Bible stories—we were actually writing the script and getting young guys, and just train them and they would go out and they would make the Bible stories so alive!

MEAKORO: And choreographing. It was our season, you know, those days.

TAMANABAE: That’s right. And we used that as a tool of evangelism, in a way in which we could capture the young people...

BOGEMBO: To share the Gospel.

TAMANABAE: And really, I think that was one of the ways in which we created an opening for the young people to start filling up the churches.

(April 20, 2010)

The revival prompted the three of them to experiment in these early years with a “diversity of ritual modalities” previously unknown to the PNG church (Yong 2010, 206). “Once we got the hang of it,” Meakoro relates, “we started getting into creativity and... we just took off” (October 18, 2012).

In 1986, an opportunity arose for Meakoro and Tamanabae to travel overseas with the Pentecostal organization Youth with a Mission (YWAM), and the timing—in those early years after independence—proved to be critical. While Tamanabae undertook evangelism training in South Carolina, Meakoro spent over three years based in Hong Kong, learning ballet, jazz dance, and break dancing. Through dance, he evangelized in the red-light districts and gay bars of Amsterdam, Haarlem, Paris, and Copenhagen. In the late 1970s, the Oro brothers had become aware of contemporary Christian music (CCM) and were particularly drawn to the songs and sounds of Andraé Crouch, Keith Green, Dallas Holm, the Imperials, and Petra. While abroad, they became ever more attracted to such music and the emerging interracial nature of CCM of the era. Being among PNG’s first overseas missionaries themselves, and encouraged by YWAM’s progressive, ethnically inclusive policies, Meakoro and Tamanabae learned firsthand that their new nation of PNG was part of a Christian transnation.

Upon Meakoro’s return to PNG in 1988, the Oro brothers formed the gospel group Higher Vision with a number of other Spirit-revived brothers, most of them also from Oro Province. This was the first of a number of widely popular PNG gospel bands they founded over the following decade, which led to their becoming major recording artists within the PNG popular music industry. Around the same time, they began a tradition of traveling at the end of each year from the different corners of the country where they were studying or working to Popondetta, the capital of their home province, where they would hold a public “Jesus march.” As Bogembo put it, “Those are moments [when] what we used to desire, we’d take it [live, amplified gospel music] out onto the streets and in the town and just explode it!” He continued, “At the time, when we brought that new sound, it’s like suddenly our people in the province started hearing, like, ‘Hey, a new sound—this is a new sound!’ ” By this time, they were writing original gospel songs in earnest and touring around parts of the country performing (April 20, 2010).

The Oro brothers began to branch out: Higher Vision soon became Tamanabae’s band, Meakoro started Voice in the Wind in the early 1990s, and several years later Bogembo formed P2-UIF with a number of PNG session musicians.20 All of the bands contained a core of Oro “clan” members; hence, this was a kind of dynasty of PNG Pentecostal music makers. As Bogembo phrased it, the bands were “all coming out of the same matrix, the same womb”—that is, a common cultural background, faith “encounter” (their term), and creative impulse (April 20, 2010).

I now turn to a discussion of the Oro brothers’ music performance aesthetic as it relates to the Pentecostal expressions of their faith in the PNG context. I term this a “spatiotemporal millennialist aesthetic” since, taken together, their music style, song repertories, and embodied communal performance practices can be understood as enfolding an apocalyptic sense of space and time that anticipates the coming reign of God. That is, although not overtly articulated as such, their oeuvre is informed by a sense of the PNG nation playing a contributing role to the larger transnational Christian community, which itself foreshadows the imminently arriving kingdom of God. Further, it represents a predilection for current and new global styles over older local ones, and by driving the experience of “high praise,” it initiates a new, future “season” of spiritual blessing.

Over the years, the Oro brothers have paid close attention to the cultural meanings of musical sounds. Indeed, for some years, they encountered intense opposition to their musical innovations from Anglican church leaders. They have been impressed by performances in PNG by Island Breeze, a YWAM peripatetic performance group that “channels the power of cultural music and dance as a visual way to share the message of Christ” (Youth with a Mission Perth 2012). Wrestling with how to understand PNG traditional music from a biblical perspective, they have consciously employed indigenous musical elements in some of their recordings. Fascinatingly, Meakoro sees the brothers’ music making as being parallel in vision to that of the high-profile and decidedly “secular” PNG transethnic fusion ensemble Sanguma:21

While we were in these pioneering stages in the gospel scenery, we were also influenced by our own [national] creative arts band, Sanguma, [which] had this kind of a vision also—they wanted to display PNG and its culture. So, they studied music and then they went deeper into the cultural aspect of it, spirits and all. We were around about the same time, but were in a very sensitive spot, as well. [chuckles] We were influenced by them, but at the same time we had a culture in the church to try and enforce, you know, with our music. But I think somewhere along the line, we didn’t cross the line, but we tapped into that [cultural] dimension because we are also Papua New Guineans. (April 20, 2010)

Here, Meakoro emphasizes that they shared with Sanguma a vision to musically represent the PNG nation and its culture. In Robbins’s terms, the Oro brothers and many other Pentecostals in PNG firmly believe that “the modern world is properly a world of nations” (2004, 170).

As I have shown, in the early post-independence revival years, P-CW song repertories arose as a response to local revival experience, although they circulated around the nation orally (a situation that continues). In the latter 1990s, following the practice in the Christian transnation beyond PNG and influenced by the worldwide success of Australian Hillsong Church songwriters Geoff Bullock and later Darlene Zschech, as well as Ron Kenoly from the United States, various members of the Oro brothers’ groups began composing and recording songs for use in corporate worship. P2-UIF later achieved a first in PNG with the inclusion of lyrics on a gospel cassette so that the songs could be used in worship, and with Tony Ando and several others, Meakoro formed the studio worship band Covenant Praise. As Tamanabae explains, the songs on their recordings followed a three-language format, indicating an intention to reach local as well as national and perhaps global worshippers: “When we started coming into the early ’90s, I think our songs, our arrangements, started changing. We started incorporating a little bit of the English version, our language—tok ples [TP, indigenous language]—and pidgin. And that actually emerged into the church scenery in the revival that hit in 1997” (April 20, 2010). Further, keeping in mind Meakoro’s comparison with Sanguma, as the Oro brothers were consciously composing Christian music for consumption across the nation, they occasionally infused a song arrangement with a local rhythmic feel. For example, Meakoro referred to the underlying rhythm of the Covenant Praise song “Sigarap” (TP, Desire or Passion) as “Sepik beat” (October 9, 2008; see Covenant Praise 2000).22

Recording engineer Digby Ho Leong confirms Tamanabae’s linking of these new songs with the 1997 revival and notes with enthusiasm how the songs began to find a place in the repertories of the Christian transnation: “When the revival was on... we wrote how many—twelve or thirteen songs—and we recorded them, and it spread like wildfire around the country. [The songs] even got down to Alice Springs [in Central Australia], and they translated them into English. And Tony’s [Tony Ando’s] songs have been sung in Malaysia!” (January 15, 2008). More recently, Meakoro has begun employing his songwriting “trademark,” in which he composes lyrics mostly in English but “slip[s] in a phrase or two of pidgin” in the hope that someday songs in a PNG language will enter the transnational worship canon (October 9, 2008).

Indigenous musical elements and languages notwithstanding, ultimately the way the Oro brothers have chosen to represent their vision of the nation is not by composing string band–style songs, nor by incorporating indigenous instruments or other musical elements, as in the approach taken by Sanguma. Rather, they adopt the sounds and style elements of Western pop, gospel, and, more recently, popular worship music. Clearly, they have always seen themselves as innovators, as brokers of new sounds and styles. This emphasis on musical currentness corresponds with their sense that Christians need to be “up to date” with God, alert to a change of “season.”

In temporal terms, the Oro brothers are guided by their understanding of the biblical notion of “season,” a Pentecostal usage derived from Jeremiah 8:7 that appears to be related to dispensationalist thinking.23 Meakoro explains that their music assists in moral transformation because it is biblically inspired and is future—and hence purpose—oriented: “I like to see my songs that I’m writing as basically going to help someone find Life.... So I like to have a source that is Life, that is good, that is wholesome, that has got the future, you know, in perspective—that has got purpose.” He continues, “On the other side is the ‘now,’ the season that we are tapping into. And while you have a source you are connecting to, one of the things that has helped me so that I stay current, I stay ‘in the now’ and I’m relevant with what I’m saying. I’m updating [that is, renewing] my material, I’m updating [renewing] my life; I’m helping others update the church—by tapping into the season” (October 9, 2008). This season is one in which God may choose to “manifest his glory” among his people in a new way, as “Abounding Grace,” the opening song of Breakthrough Praise and Ando and Meakoro’s best-known worship song, puts it.24

In Robbins’s study of the Urapmin, a group of 390 people who live in the remote West Sepik Province of PNG, most of whom are Pentecostal Christians, he documents a “redemption ritual” they call “Spirit disko” (2004, 281–88). This bears some resemblance to “high praise” and P-CW more generally, although it is held separately from worship and outreach services. In any case, as Robbins explains, “it is through this institution that the Urapmin most fully elaborate their vision of collective salvation” (305). Interestingly, the 2010 SOS, with its musical Breakthrough Praise night and Praise Extravaganza model, coincided with a decision among the small Oro Pentecostal ministry groups living in Port Moresby, and the many musicians who had been members over the years of one or another of the Oro gospel groups, to “merge.” As Meakoro put it, “[We] are more concerned about the corporate destiny than our own individual streams. Because we are feeling it’s like the corporate destiny of the church, the corporate destiny of the nation—more for a corporate pursuit” (April 20, 2010). There was a sense that it was time to turn away from the individualism that had come to characterize their musical pursuits for several decades and to prepare for a new “season” with a new strategy. Tamanabae summed up their several decades of gospel music making with a teleological reflection: “All this time we’ve been saying, ‘Let’s just keep building; let’s keep preparing it. We don’t know what’s going to happen but something’s going to open up for us. We never know—it may come in its full timing!’ ” (April 20, 2010).

In this chapter, I have examined aspects of the liturgy of P-CW as it has come to be practiced across PNG over the last two decades and outlined the historical circumstances that saw it emerge as a new form of shared sacred Christian ceremony incorporating elements of popular, traditional, and national culture. Through a case study of the Oro brothers, who in their youth were inspired by a Pentecostal revival in their province and who went on to both innovate in the field of gospel music and creatively enliven worship locally and nationally, I have attempted to uncover the processes involved in establishing the liturgical form. Finally, I have proposed that the Oro brothers operate within the framework of a spatiotemporal millennialist aesthetic. This is encapsulated in the logo screen printed on the back of T-shirts worn at the SOS Breakthrough Praise event:

PNG

Praise Extravaganza

United for Purpose

Destiny is Dawning

“PNG” and “United for Purpose” indicate a relating to space as nation. “Praise Extravaganza” conveys participation in “extravagant” performance and the entering into musical and sacred time. And “Destiny is Dawning” announces an imminent future age of blessing and fulfillment. Considering the three strands of the logo together and the work the Oro brothers have done to shake up and transform worship nationally, we might better understand their belief that through “high praise” their merged congregations, and the PNG nation more broadly, can experience moral transformation in readiness for “the coming of our King.”25

I am indebted to Pastor Tony Ando, Pastor Peter Bogembo, Pastor Daniel Meakoro, Pastor Oswald Tamanabae, Digby Ho Leong, Edric Ogomeni, and Iara Eliakim for their time, patience, humor, and friendship. In Lae, thanks to Angela Panap of Joseph Kingal Ministries, Pastor Ernest Menemo of City Tabernacle Church–CRC, and Kich Bernard of Our Saviour Lutheran. I am particularly grateful to Don Niles of the Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies for advice and encouragement over thirty years. Fieldwork was funded by the New Frontiers grant scheme of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney. Photographs, song-text transcription, and all translations are mine.

1. Papua New Guinea is an independent state with a population of around seven million. Located north of Australia in the southwestern Pacific Islands subregion generally designated Melanesia, it is one of the most linguistically and culturally diverse regions of the world, where well over one thousand distinct languages are spoken.

2. The text of “Abounding Grace,” by Tony Ando and Daniel Meakoro, is reproduced with the composers’ permission. Breakthrough Praise was held on April 10, 2010, in Port Moresby, PNG. A field recording of an excerpt of this session, with additional analytical notes, can be found on the author’s website, http://www.melanesianmusicresearch.com, under Libraries: Sound Recordings: Papua New Guinea. Also uploaded there are excerpts from field recordings of Pentecostal-charismatic worship accompanied by a fulset (electric rock band) from an outdoor public evangelistic crusade in Lae, on the northern side of PNG.

3. These groups are also affiliated with the Malaysia-based I.S.A.A.C. network. See http://www.jonathan-david.org.

4. According to Allan Anderson, those participating in Pentecostal and charismatic worship are given an opportunity to “pray simultaneously, to dance and sing during the ‘praise and worship,’ to exercise the gifts of the Spirit, to respond to the ‘altar call,’ and to call out their approval of the preaching with expletives like ‘Amen!’ and ‘Hallelujah!’ and with applause and laughter” (2004, 9).

5. Webb’s (2011) detailed discussion of Pentecostal-charismatic worship as practiced in and around the city of Lae provides contextual information relevant to the present study.

6. The postmissionary “era” in PNG more or less coincides with political independence in 1975 and the earliest phase of decolonization, and it signals the beginning of a time of financial and institutional independence for local Protestant (including Pentecostal) churches (see Howell 2008, 23).

7. While P-CW is commonly associated with Pentecostalists, it has been adapted for use by many different denominations, both Catholic and Protestant.

8. I draw on the following interviews in this chapter: Digby Ho Leong and Edric Ogomeni, January 15, 2008, Port Moresby, PNG (1 hr., 14 min.); Angela Panap, October 7, 2008, Lae, PNG (43 min.); Daniel Meakoro, October 9, 2008, Port Moresby, PNG (1hr., 20 min.); Peter Bogembo, Daniel Meakoro, and Oswald Tamanabae (group interview), April 20, 2010, Port Moresby, PNG (1 hr., 21 min.); Daniel Meakoro (Skype conversation), October 18, 2012 (15 min.). In the text, I reference these by date. In quoting from interviews, I have omitted minor repetitions.

9. In interview and conversation, the three referred to one another as brothers, an overlap of a Christian usage, shared history, and provincial origin.

10. Tony Ando was unavailable at the time I conducted the interviews on which this case study is based. I subsequently met and interviewed him in February 2013, although this data is not drawn upon in the chapter.

11. For one example, in 2008 the well-resourced Pentecostal organization Joseph Kingal Ministries of Lae launched Flame of Touch, a “national spiritual strategic plan” to evangelize each of the nation’s eighty-nine electorates over twenty years, with five major crusades per year (Aihi 2008).

12. The Cordyline fruticosa, a plant native to many parts of the Pacific Islands, has sacred connotations. Its leaves are often worn in dance performance.

13. Consult field recordings of P-CW on the author’s website, http://www.melanesianmusicresearch.com.

14. OneBell (from wanbel; TP, of the same conviction); Kisim i go (TP, Take it out).

15. In a YouTube video performance of the OneBell song “Yu yet yu Namba Wan” (TP, You alone are Lord), Kawaipa plays guitar and sings a duet with Australian Hillsong musician Raymond Badham (“Ray Badham” 2012). Interestingly, in terms of musical glocalization, both the PNG and Australian musicians sing in Tok Pisin, and it is Badham, the Australian, who provides a lead guitar introduction and coda comprising a genericized string band guitar motif. Both Badham and Kawaipa reproduce the ailan reggae (PNG English, island reggae) guitar strum and overall “feel” common in PNG studio-produced pop music from the early 1990s.

16. The Oro “brothers” form the core of a larger group of influential musicians that includes Oswald’s brothers Steve and Brian, Tony Ando, and Edric Ogomeni, as well as John Uware, who comes from the Orokaiva region.

17. According to Robbins, “second-stage conversion” occurs “when Christian meanings have come to shape people’s world to such an extent that those meanings themselves, rather than ones drawn from traditional culture, begin to provide the motive for conversion” (2004, 215).

18. The term used by Port Moresby–based CRC members for their evangelistic excursions into the provinces (see Gallagher 2011, 202).

19. In PNG, lokal (TP, local) is a synonym for stringben (TP, string band). Meakoro’s usage of the word is interesting—an unintended pun, perhaps?

20. The group’s alphanumeric name derives from the registration code of an aircraft owned by the CRC that crashed in rugged terrain in PNG in 1992, resulting in the death of the pastor pilot and passengers. For the band, P2 came to stand for “Two Partners” and UIF for “United in Fellowship.”

21. See Crowdy (2004) for a history of this ensemble.

22. This is a studio-created approximation of a rhythmic “feel” derived from a string band strumming style from the Sepik River region, created by juxtaposing the melody in triple meter against the quadruple metrical structure set up by drums.

23. For an explanation of dispensationalist theology and an account of its impact on a PNG society, see Robbins (2004, 158–68).

24. In the dispensationalist system, the current church age is marked by the dispensation of grace.

25. From the text of “Abounding Grace.”

Aihi, D. 2008. “20-Year Crusade Plan Launched.” The National, June 12.

Anderson, Allan. 2004. An Introduction to Pentecostalism: Global Charismatic Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Covenant Praise. 2000. Spirit of the Word. Port Moresby: Chin H. Meen. Cassette tape.

Crowdy, Denis. 2004. “From Black Magic Woman to Black Magic Men: The Music of Sanguma.” Ph.D. diss., Macquarie University.

Farhadian, Charles. 2007. “Worship as Mission: The Personal and Social Ends of Papuan Worship in the Glory Hut.” In Christian Worship Worldwide: Expanding Horizons, Deepening Practices, edited by Charles Farhadian, 171–95. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans.

Gallagher, Sarita. 2011. “Abrahamic Blessing Motif as Reflected in the Papua New Guinean Christian Revival Crusade Movement: Blesim bilong Papa God.” Ph.D. diss., Fuller Theological Seminary.

Handman, Courtney Jill. 2010. “Schism and Christianity: Bible Translation and the Social Organization of Denominationalism in the Waria Valley, Papua New Guinea.” Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago.

Howell, Brian. 2008. Christianity in the Local Context: Southern Baptists in the Philippines. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

“The Kimbe Holy Spirit Crusade.” 2012. YouTube video, 5:00. Posted by Fred Evans, September 19. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o_JqMIJKcPQ.

Midian, Andrew. 1999. The Value of Indigenous Music in the Life and Ministry of the Church: The United Church in the Duke of York Islands. Port Moresby: Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies.

“Ray Badham, Robin Kawaipa, and Hillsong College Team@ PNG EncounterFirst 2012 Conference.” 2012. YouTube video, 2:26. Posted by Robin Kawaipa, June 12. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vImcxvBn7mM.

“Revival Celebrations in Papua New Guinea.” 2012. YouTube video, 3:34. Posted by Fred Evans, August 28. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0EqTz63kcT0.

Robbins, Joel. 2004. Becoming Sinners: Christianity and Moral Torment in a Papua New Guinea Society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Slobin, Mark. 2010. Folk Music: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Strathern, Andrew, and Theodoor Ahrens. 1986. “Experiencing the Christian Faith in Papua New Guinea.” Melanesian Journal of Theology 2 (1): 8–21.

Webb, Michael. 2011. “Palang Conformity and Fulset Freedom.” Ethnomusicology 55 (3): 445–72.

Yong, Amos. 2010. In the Days of Caesar: Pentecostalism and Political Theology. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans.

Youth with a Mission Perth. 2012. “Island Breeze.” http://www.ywamperth.org.au/missions/island-breeze/.