As with the commanders, the troops in Sheridan’s Shenandoah campaign were among the best soldiers available to both sides in 1864. At the beginning of the year, the troops in the Shenandoah had been leftovers—locally recruited, or simply shifted into the area and considered too unimportant to move to a more active theater. Grant’s 1864 spring offensive, with simultaneous drives on several fronts—including into the Shenandoah Valley—underscored the importance of the valley to the South.

Lee countered the Northern threat by shifting Early’s Corps to the valley. Among the best soldiers in Lee’s army, Early and his men did what Lee expected them to do. Despite being outnumbered two to one by Union forces, the Confederates under Early swept the Union troops from the valley. Early even delivered a secondary objective of the transfer; his lightning raids into Pennsylvania and Washington DC drew troops away from Grant at Petersburg.

In a sense, Early was too successful. Given the skill of the Confederates guarding the valley, Grant realized that quantity alone would not yield victory. The valley was too important to cede to the South, however. The reinforcements Grant sent were among his best—men who had been tested in battle, and who performed reliably. Even troops drawn from other theaters, such as the XIX Corps’ divisions brought from the Mississippi, were the best available. This, in turn, forced Lee to dispatch still more combat veterans to the valley. The loser in the upcoming contest might blame many factors for defeat—inadequate supplies, poor lines of communication, or even bad luck—but a lack of quality troops would be no valid excuse for failure. Neither side had to apologize for the troops in the campaign.

Washing day for an army on the march. Clean clothes and marching were equally important for soldiers in the Civil War, regardless of side. Men of both armies would remember days like this. (LOC)

Grant built the Union Army of the Shenandoah from four sources: the Army of West Virginia, the Army of the Potomac’s VI Corps and the Cavalry Corps, and the Union’s XIX Corps.

The Army of West Virginia was made up of the troops originally in the region, roughly two infantry divisions, one cavalry division, and an artillery brigade. These troops were commanded by major-generals Franz Sigel and David Hunter earlier in 1864. In August that year, these soldiers were reorganized into the Department of West Virginia. It contained 26,000 men: 14,000 infantry, 8,500 cavalry, and 3,500 artillerymen. A sizable percentage was required to guard West Virginia, western Maryland, western Virginia and the approaches to Pennsylvania. They were also needed to protect supply lines and communications and to guard against raiding Confederate partisan units. Thus, Sheridan could only use 60 percent of these men in his field army.

Sheridan reorganized these troops. He took roughly half the cavalry, creating one cavalry division, which he assigned to his Cavalry Corps as the 2nd Division. Of the infantry, he took 12,000 men, divided into three infantry divisions: the 1st, 2nd (Kanawha), and Provisional divisions. The 1st and 2nd divisions, existing formations, were used as field formations. The Provisional Division, made up of replacements and garrison troops, was kept as a reserve and rarely exceeded a brigade in strength. This force was designated the Army of West Virginia.

These troops may have been chased out of the valley by Early’s offensive in June, but this represented a failure of army leadership, not a weakness among these soldiers. One infantry division—the Kanawha—had a distinguished combat history, and numbered among its officers two men that later became Presidents of the United States: Rutherford B. Hayes and William McKinley.

With a field force that ranged between 12,000 and 14,000 men, the Army of West Virginia was the size of a Union corps, and was treated as such tactically during Sheridan’s campaign. Histories often refer to it as VIII Corps, perhaps confusing it with the actual formation of that name, commanded by Lew Wallace, which defended Washington DC.

Future President William McKinley enlisted as a private in the 23rd Ohio Infantry in 1861. By 1864 he had risen to the rank of captain. He served on Brigadier-General George Crook’s staff during Sheridan’s Shenandoah campaign. (AC)

Most of the rest of the Union Army of the Shenandoah was drawn from the Army of the Potomac. Grant had been forced to detach VI Corps to Washington as a result of Early’s July raid. Rather than use it in static defense of the capital, Grant made virtue out of necessity. He gave VI Corps to Sheridan, to help clear Early out of the Shenandoah. Grant also threw in two divisions of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps.

VI Corps was one of the Union army’s best corps. Organized in 1862, it had participated in most of the Army of the Potomac’s campaigns, from George B. McClellan’s 1862 Peninsula Campaign through Grant’s Overland Campaign in 1864. At Gettysburg it was numerically the largest corps in the Union army.

After the Army of the Potomac’s reorganization in spring 1864, VI Corps numbered over 24,000 men. VI Corps fought a hard campaign, and by August its numbers had been significantly reduced. Returns for August reported 16,414 officers and men present. The men who remained were experienced, long-term combat veterans. They knew how to fight, were steady in battle, and had survived some of the toughest engagements of the Civil War.

The rest of the Army of the Potomac’s contribution came from the Cavalry Corps. For the first two years of the war the Cavalry Corps had performed poorly. Its results and reputation began to change in 1863, starting with the Battle of Brandy Station. It turned in a creditable performance at Gettysburg, seizing ground that allowed the Union army to gain a strong position running from the Round Tops to Culp’s Hill. By August 1864, led by Phil Sheridan, the Cavalry Corps had been transformed into an elite formation.

The Union cavalry was of limited use in eastern Virginia while the Army of the Potomac was mired in a siege at Petersburg. It was ideal for the mobile warfare that an attack on the Shenandoah Valley involved, so Grant added two of its three divisions to Sheridan’s forces, keeping one for himself. The 1st and 3rd divisions of the Cavalry Corps brought Sheridan over 11,000 officers and men, a combination of cavalry and attached horse artillery. With the cavalry from the Department of West Virginia added to this Cavalry Corps as its 2nd Division, Sheridan had one of the most formidable collections of horse soldiers available to the Union army for his campaign.

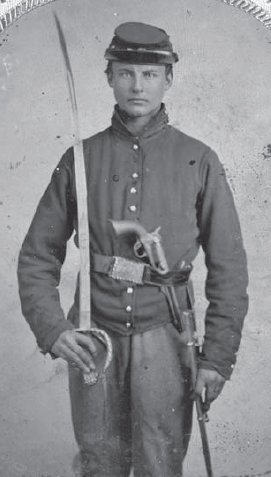

A private from the 67th Pennsylvania Regiment. The 67th Pennsylvania was assigned to the 2nd Brigade of the 3rd Division of VI Corps. (AC)

Finally, to bulk out the Army of the Shenandoah, Grant gave Sheridan two divisions from the United States Army’s XIX Corps. The latter had been part of Nathaniel Banks’s Army of the Mississippi. They fought at Port Hudson in 1863, and participated in the Red River Campaign in the spring of 1864.

The Red River Campaign ended disastrously, and XIX Corps had relatively little to do by summer. Grant decided its soldiers would be better used actively serving in the Virginia Theater than in reserve in a military backwater like Louisiana. Grant transferred two of its divisions east and they were on hand when he began organizing the new push in the Shenandoah. He gave the two divisions to Sheridan, providing the Army of the Shenandoah with an additional 14,000 infantry. These men were veteran troops, tested in battle.

These soldiers gave Sheridan a force of 45,000 men for his offensive, as well as reserves to draw upon in case of need. His troops were well supplied, well equipped and well armed. Most were men who had long-term enlistments. The majority, due to the units involved, were volunteers. Most were also combat veterans. Almost all had fought in the various Union spring 1864 offensives. Some were veterans of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.

Most infantry units had late-model 1861 Springfield or 1853 Enfield rifled muskets. The Union cavalry were equipped with repeating rifles—a force multiplier. The rate of fire that repeating Henry or Spencer rifles wielded by Union cavalry troopers permitted a dismounted cavalry regiment to stop an advancing Confederate infantry brigade, despite the longer range of the infantry’s rifles. Additionally, the Army of the Shenandoah had 100 artillery pieces assigned to its field corps. These were light cannon, capable of rapid movement.

An artillery private in the United States Army offers a stern-faced pose in a formal portrait. With his artillery sword at present and a pistol stuck in his belt, he attempts to impress the folks back home. (LOC)

The Union army was suffering from manpower problems by summer 1864. To make up a shortage of infantry, it had started to pull heavy artillery regiments out of their fortifications, strip these regiments of their artillery, and re-equip them as infantry. It was also dismounting surplus cavalry regiments and using these as ad hoc infantry. Grant had done his best to give Sheridan the best troops available, however. Of the nearly 100 regiments assigned to infantry brigades in the Army of the Shenandoah, only four were heavy artillery or dismounted cavalry.

One unusual aspect of the Union Army of the Shenandoah was an absence of “Colored” units. The Army of West Virginia was one of the few “all-white” armies in the Union order of battle by 1864. The Army of the Potomac had enough Colored regiments that it eventually formed a corps exclusively from Colored troops. XIX Corps was one of the first Union formations to field large numbers of these troops. Yet VI Corps was all white, as the two cavalry divisions detached from the Army of the Potomac (1st and 3rd) had no Colored cavalry regiments and the two divisions sent east from XIX Corps consisted solely of white soldiers.

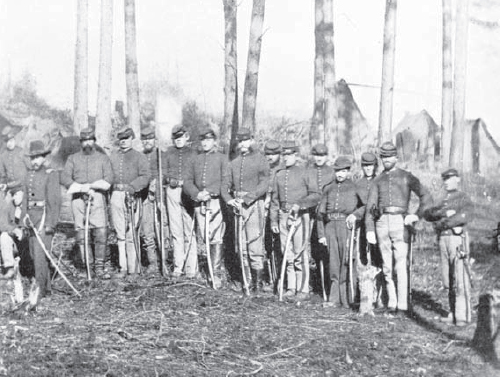

Troopers of the 1st United States Cavalry Regiment at Brandy Station in February 1864. Six months later it formed part of Brigadier-General Wesley Merritt’s 1st Cavalry Division, fighting in the Shenandoah Valley. (AC)

Opposing the Union forces was the Confederate Army of the Valley. At the start of the campaign this consisted of Jubal Early’s corps augmented by the remaining Confederate field forces in the Shenandoah Valley at the end of the Union spring offensives. To offset the reinforcements sent to Sheridan, it was reinforced in August by a second corps sent from the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee intended this corps as a loan, however, to be returned at the earliest opportunity. In addition, Early could call upon the services of several regiments of partisan cavalry. These were locally raised formations, enrolled in the Confederate armies but fighting exclusively as guerrillas, attacking lines of communication.

Early and his corps had been shifted to the valley in June 1864, as Lee’s response to the Union’s spring offensives. Officially II Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, by June 1864 it was almost universally called “Early’s Corps.” Organized in 1862, it was originally commanded by the legendary Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. Following the latter’s death at Chancellorsville in 1863, its command was inherited by Richard Ewell. Early took command on May 29, 1864, after Lee, dissatisfied with Ewell’s performance as a corps commander, shuffled Ewell off to a backwater assignment.

This corps had one of the most celebrated histories in the Army of Northern Virginia. It formed the core of “Jackson’s Foot Cavalry” that hustled the Union out of the Shenandoah Valley in 1862. It led the flanking movement that routed the Union army at Chancellorsville. It smashed the Union garrison holding Winchester, Virginia at the Second Battle of Winchester in mid-June 1863.

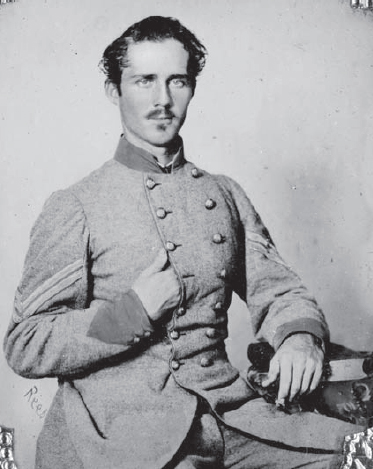

Luther Hart Clapp of Company C, 37th Virginia Infantry Regiment. The 37th Virginia was part of Terry’s Brigade in Gordon’s Division. Terry’s Brigade contained the remnants of 14 Virginia regiments decimated during the Overland Campaign. (LOC)

By August 1864 the corps had been whittled down to three understrength infantry divisions. While its divisions officially listed 34,515 men on its rosters, those actually present totaled just over 10,000 men. On a good day those present for duty—excluding the sick and otherwise unavailable for fighting—might number between 8,200 and 8,300 men. The corps had three battalions of artillery, with 35 light field guns.

However, the soldiers present for combat were the best available. It included survivors from the old “Stonewall Brigade” (commanded by Jackson at First Bull Run). In 1864 it was leavened by the veterans of Jackson’s campaigns and Gettysburg, and virtually all the men present in August had fought in the Overland Campaign, and in Early’s offensives in the Shenandoah and the raids into Maryland, Pennsylvania and Washington DC that summer. The 10,000 that remained were among the most experienced troops left in the Army of Northern Virginia.

These troops were underfed, short on ammunition, and frequently had to fight barefoot in tattered uniforms or civilian clothing due to Confederate supply shortages. Yet fight they did. Since being detached from Lee’s direct command, they chased the Yankees out of the Shenandoah Valley, twice raided Pennsylvania, burning Harrisburg, and drove the Union army into the fortifications guarding Washington DC.

Supplementing Early’s Corps were troops originally stationed in the valley at the beginning of 1864. By August the field portion of this force had been reduced to the equivalent of a division each of infantry and cavalry and 13 pieces of field artillery. As with the men in Early’s Corps, these soldiers were long-term veterans. The regiments assigned to the valley in 1864 were generally from western Virginia, including the Shenandoah counties and present-day West Virginia.

These men spent most of the war fighting in western Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and eastern Tennessee. These were the forces that had faced Franz Sigel’s corps and David Hunter’s Army of Western Virginia in the spring. They fought at New Market and Lynchburg earlier in the year, and were intimately familiar with the Shenandoah Valley. Their numbers were small—perhaps 2,500 to 3,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry—but, as with Early’s Corps, the ones that remained were the fighters.

These units were joined by two additional divisions under the command of Lieutenant-General Richard H. Anderson: Major-General Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry division and Major-General Joseph B. Kershaw’s infantry division. Both had 20 field guns. Sent from the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee intended these troops as temporary reinforcements, to counter Sheridan’s buildup. The cavalry division—with fewer than 2,000 men—remained in the valley for the rest of the campaign. Kershaw’s Division, which numbered 3,800 at the end of August, was recalled to the Army of Northern Virginia in early September, only to be ordered back to the valley following the Third Battle of Winchester on September 19.

Bernard Bluecher Graves served in the Amherst Artillery, part of Nelson’s Battalion. A corporal, Graves fought in most of the major battles during the Shenandoah campaign. He was captured at Waynesboro on March 2, 1865. (LOC)

As with Early’s Corps, the men from these two divisions were long-term veterans. Kershaw’s Division had fought with the Army of Northern Virginia from the Peninsula Campaign in 1862 through the Overland Campaign in 1864. It was also part of Longstreet’s Corps dispatched to Tennessee in the last half of 1863, and had fought at Chickamauga and participated in besieging Knoxville. The three brigades that made up the cavalry division rode with J.E.B. Stuart until his death in 1864. One regiment had had Stuart as their first colonel. Other regiments had participated in Jackson’s Valley Campaign in 1862.

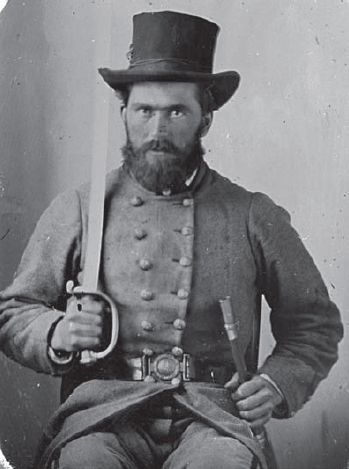

A cavalry trooper from Brigadier-General Thomas Lafayette Rosser’s Laurel Brigade. The Laurel Brigade was sent to the Shenandoah after Fisher’s Hill to reinforce the Confederate cavalry in Early’s army. (LOC)

The Army of the Valley was “white.” Most of its soldiers came from farming backgrounds, many from small family farms. Their absence meant hardship for their families. Relatively few owned slaves.

In total, Early could field no more than 20,000 men during Sheridan’s Valley Campaign. Frequently, he could only muster 10,000 or fewer men. Nor could he expect replacements for his losses. The Confederacy’s manpower barrel was empty. Yet Early’s troops still gave him a few advantages. Many were familiar with the terrain they were fighting over. All were tough—three years of hard fighting had scoured away the weak, lame, and lazy. Those still fighting were fiercely loyal to their states. Those that were not had gone home.

Two final units that bear mention are two partisan cavalry battalions: Lieutenant-Colonel John S. Mosby’s Rangers or Raiders (43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry) and Captain John H. McNeill’s Rangers (Company E of the 18th Virginia Cavalry). They were not present at the major battles during Sheridan’s Valley Campaign, and between them never fielded more than 650 men. Yet both had an influence disproportionate to their tables of organization.

The Southern States raised several dozen partisan cavalry regiments and battalions in the early years of the Civil War. These units were intended to operate behind Union lines as irregulars, disrupting Union supply lines and communications. Lee’s unease with guerrilla warfare caused most partisan units to be disbanded or reorganized as standard cavalry at the start of 1864. Only Mosby’s Rangers and McNeill’s Rangers, both in Virginia’s western counties, were retained as partisans.

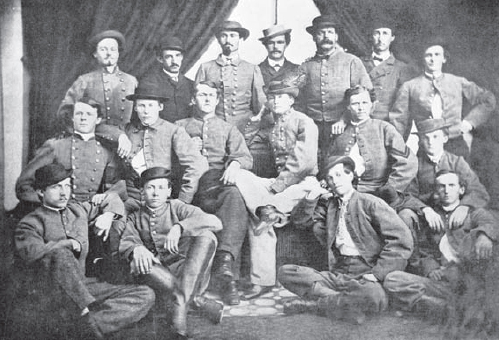

Colonel John S. Mosby and 16 members of the 43rd Virginia Cavalry Battalion—better known as Mosby’s Rangers. Mosby is the fourth figure from the left in the second row, sitting with his legs crossed. (AC)

These battalions operated in small groups of 30 to 150 men, generally at night, and attacked Union lines of communications. They fought in uniform, but the uniforms were informal. In some cases, gray clothing sufficed. They blended into the civilian population when not fighting, and permitted civilians, not formally enlisted, to accompany them on raids. A relative handful, they tied down tens of thousands of Union troops in protecting railroads, depots, and telegraph lines. The Union army considered them guerrillas and illegal combatants, not entitled to protection as prisoners of war when captured.

These rangers made a significant contribution to Early’s ability to hold the Shenandoah Valley by denying Sheridan’s field army the troops required to protect Union lines. Yet they also contributed significantly to the bitterness with which Sheridan’s Valley Campaign was fought. The presence of partisan rangers in the Union rear was a major reason for Sheridan’s decision to burn the valley out in September and October 1864.

6th United States Cavalry (Escort)

VI ARMY CORPS

1st Michigan Cavalry, Co. G (Escort)

1st Division

1st Brigade

4th New Jersey

10th New Jersey

15th New Jersey

2nd Brigade

2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery

65th New York

121st New York

95th Pennsylvania1

96th Pennsylvania1

3rd Brigade2

37th Massachusetts

49th Pennsylvania

82nd Pennsylvania

119th Pennsylvania

2nd Rhode Island (battalion)

5th Wisconsin (battalion)

2nd Division

1st Brigade

62nd New York

93rd Pennsylvania

98th Pennsylvania

102nd Pennsylvania

139th Pennsylvania

2nd Brigade

2nd Vermont

3rd Vermont

4th Vermont

5th Vermont

6th Vermont

11th Vermont

3rd Brigade

7th Maine3

49th New York

77th New York

122nd New York

61st Pennsylvania (battalion)

3rd Division

1st Brigade

14th New Jersey

106th New York

151st New York

184th New York (battalion)4

87th Pennsylvania4

10th Vermont

2nd Brigade

6th Maryland

9th New York Heavy Artillery

110th Ohio

122nd Ohio

126th Ohio

67th Pennsylvania

138th Ohio

Artillery Brigade

Maine Light Artillery, 5th Battery (E)

Massachusetts Light Artillery, 1st Battery (A)

1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, Battery C

1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, Battery G

1st United States Artillery, Battery M

XIX ARMY CORPS

1st Division

1st Brigade

29th Maine

30th Massachusetts

90th New York5

114th New York

116th New York

153rd New York

2nd Brigade

12th Connecticut

160th New York

121st New York6

47th Pennsylvania

4th Vermont

3rd Brigade7

30th Maine

133rd New York

162nd New York

165th New York

173rd New York

Artillery

New York Light Artillery, 5th Battery

2nd Division

1st Brigade

9th Connecticut

12th Maine

14th Maine

26th Massachusetts

14th New Hampshire

75th New York

2nd Brigade

13th Connecticut

11th Indiana

22nd Iowa

3rd Massachusetts Cavalry (dismounted)

131st New York

159th New York

3rd Brigade

38th Massachusetts

128th New York

156th New York

175th New York

176th New York

4th Brigade

8th Indiana

18th Indiana

24th Iowa

28th Iowa

Artillery

Maine Light Artillery, 1st Battery (A)

Reserve artillery

Indiana Light Artillery, 17th Battery

1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, Battery D

ARMY OF WEST VIRGINIA (VIII ARMY CORPS)

1st Division

1st Brigade

34th Massachusetts

5th New York Heavy Artillery, 2nd Battalion

116th Ohio

123rd Ohio

1st West Virginia

4th West Virginia

12th West Virginia

3rd Brigade

23rd Illinois (battalion)

54th Pennsylvania

10th West Virginia

11th West Virginia

15th West Virginia

2nd Division

1st Brigade

23rd Ohio

36th Ohio

5th West Virginia

13th West Virginia

2nd Brigade

34th Ohio (battalion)

91st Ohio

9th West Virginia

14th West Virginia

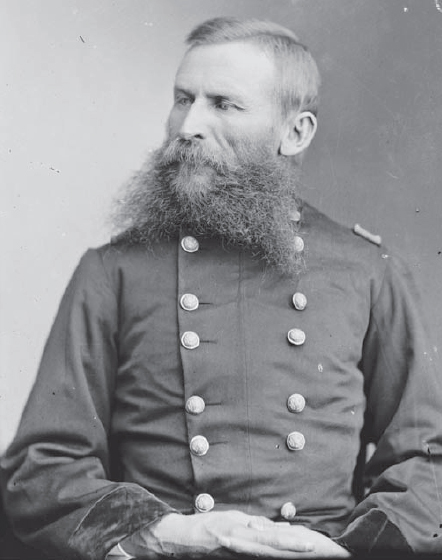

Brigadier-General George R. Crook replaced David Hunter as the commander of the Army of West Virginia in August 1864. The army’s cavalry was reassigned to the Army of the Shenandoah’s Cavalry Corps, leaving Crook in operational charge of two full-strength and one brigade-sized infantry divisions. (LOC)

Artillery Brigade

1st Ohio Light Artillery, Battery L

1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery, Battery D

1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, Battery G6

5th United States Artillery, Battery B

CAVALRY CORPS

1st Rhode Island Cavalry (Escort)

1st Division

1st Brigade

1st Michigan Cavalry

5th Michigan Cavalry

6th Michigan Cavalry

7th Michigan Cavalry

25th Michigan Cavalry7

2nd Brigade

4th New York Cavalry

6th New York Cavalry

9th New York Cavalry

19th New York Cavalry (1st Dragoons)

17th Pennsylvania Cavalry8

3rd Brigade9

1st Maryland Potomac Home Brigade

2nd Massachusetts Cavalry

25th New York Cavalry

Reserve Brigade

19th New York (1st Dragoons) Cavalry

6th Pennsylvania Cavalry6

1st United States Cavalry

2nd United States Cavalry

5th United States Cavalry

2nd Division

1st Brigade

8th Ohio Cavalry (detachment)

14th Pennsylvania Cavalry

22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry

2nd Brigade

1st New York Cavalry

1st West Virginia Cavalry

2nd West Virginia Cavalry

3rd West Virginia Cavalry

Artillery

5th United States Artillery, Battery L

3rd Division

1st Brigade

1st Connecticut Cavalry

3rd New Jersey Cavalry

2nd New York Cavalry

5th New York Cavalry

2nd Ohio Cavalry

18th Pennsylvania Cavalry

2nd Brigade

3rd Indiana Cavalry

1st New Hampshire Cavalry

8th New York Cavalry

22nd New York Cavalry

1st Vermont Cavalry

Horse Artillery

New York Light Artillery, 6th Battery10

1st United States Artillery, Battery K and Battery L11

2nd United States Artillery, Battery B and Battery L

2nd United States Artillery, Battery D

2nd United States Artillery, Battery M

3rd United States Artillery, Battery C, Battery F, and Battery K

4th United States Artillery, Battery C and Battery E

Notes on Union forces

1. Guarding trains during the the Third Battle of Winchester (September 19) and not engaged in the battle.

2. At Winchester during the Battle of Cedar Creek (October 19).

3. Replaced by 1st Maine (Veteran) Infantry after the Third Battle of Winchester.

4. One battalion of the 184th New York replaced one battalion of the 87th Pennsylvania after the Third Battle of Winchester.

5. Added after September 20.

6. Detached after September 20.

7. In reserve at Harpers Ferry during the Third Battle of Winchester (September 19).

8. Assigned to 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, VI Corps during the Battle of Cedar Creek (October 19).

9. Dissolved September 9.

10. Assigned to 1st Brigade, 1st Division, Cavalry Corps after September 20.

11. Assigned to 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, Cavalry Corps after September 20.

Company D of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry was part of the 1st Cavalry Division during Sheridan’s campaign in the Shenandoah. (AC)

II CORPS (EARLY’S CORPS), ARMY OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA

Rodes’s (later Ramseur’s) Division

Grimes’s Brigade

32nd North Carolina Infantry

43rd North Carolina Infantry

45th North Carolina Infantry

53rd North Carolina Infantry

2nd North Carolina Infantry Battalion (independent)

Cox’s Brigade

1st North Carolina Infantry

2nd North Carolina Infantry

3rd North Carolina Infantry

4th North Carolina Infantry

14th North Carolina Infantry

30th North Carolina Infantry

Cook’s Brigade

4th Georgia Infantry

12th Georgia Infantry

21st Georgia Infantry

44th Georgia Infantry

Battle’s Brigade

3rd Alabama Infantry

5th Alabama Infantry

6th Alabama Infantry

12th Alabama Infantry

61st Alabama Infantry

Gordon’s Division

Hays’s Brigade

5th Louisiana Infantry

6th Louisiana Infantry

7th Louisiana Infantry

8th Louisiana Infantry

9th Louisiana Infantry

Evans’s Brigade

13th Georgia Infantry

26th Georgia Infantry

31st Georgia Infantry

60th Georgia Infantry

61st Georgia Infantry

12th Georgia Infantry Battalion (independent)

Stafford’s Brigade

1st Louisiana Infantry

2nd Louisiana Infantry

10th Louisiana Infantry

14th Louisiana Infantry

15th Louisiana Infantry

Terry’s Brigade

2nd Virginia Infantry

4th Virginia Infantry

5th Virginia Infantry

27th Virginia Infantry

33rd Virginia Infantry

21st Virginia Infantry

25th Virginia Infantry

42nd Virginia Infantry

44th Virginia Infantry

48th Virginia Infantry

50th Virginia Infantry

10th Virginia Infantry

23rd Virginia Infantry

37th Virginia Infantry

Ramseur’s (later Pegram’s) Division

Pegram’s Brigade

13th Virginia Infantry

31st Virginia Infantry

49th Virginia Infantry

52rd Virginia Infantry

58th Virginia Infantry

Johnston’s Brigade

5th North Carolina Infantry

12th North Carolina Infantry

20th North Carolina Infantry

23rd North Carolina Infantry

Godwin’s Brigade

6th North Carolina Infantry

21st North Carolina Infantry

54th North Carolina Infantry

57th North Carolina Infantry

1st North Carolina Infantry Battalion (independent)

Artillery Division

Braxton’s Battalion

Cutshaw’s Battalion

McLauglin’s (later King’s) Battalion

Nelson’s Battalion

Breckinridge’s (later Wharton’s) Division

Wharton’s Brigade

45th Virginia Infantry

50th Virginia Infantry

51st Virginia Infantry

30th Virginia Infantry Battalion,

Sharpshooters

Echol’s Brigade

22nd Virginia Infantry

23rd Virginia Infantry Battalion (independent)

26th Virginia Infantry Battalion (independent)

Smith’s Brigade

36th Virginia Infantry

60th Virginia Infantry

45th Virginia Infantry Battalion (independent)

Thomas Legion

Lomax’s Division (Cavalry)

Imboden’s Brigade

18th Virginia Cavalry

23rd Virginia Cavalry

62nd Virginia Cavalry

McCausland’s Brigade

14th Virginia Cavalry

16th Virginia Cavalry

17th Virginia Cavalry

25th Virginia Cavalry

37th Virginia Cavalry Battalion (independent)

Bradley T. Johnson’s Brigade

8th Virginia Cavalry

21st Virginia Cavalry

22nd Virginia Cavalry

34th Virginia Cavalry Battalion (independent)

36th Virginia Cavalry Battalion (independent)

Jackson’s Brigade

2nd Maryland Cavalry

19th Virginia Cavalry

20th Virginia Cavalry

46th Virginia Cavalry Battalion (independent)

47th Virginia Cavalry Battalion (independent)

UNITS FROM I CORPS (ANDERSON’S CORPS)1

Kershaw’s Division2

Conner’s Brigade

2nd South Carolina Infantry

3rd South Carolina Infantry

7th South Carolina Infantry

8th South Carolina Infantry

15th South Carolina Infantry

20th South Carolina Infantry

3rd South Carolina Infantry Battalion (independent)

Wofford’s Brigade

16th Georgia Infantry

18th Georgia Infantry

24th Georgia Infantry

3rd Georgia Infantry

Cobb’s Legion (Georgia)

Phillips’s Legion (Georgia)

Humphrey’s Brigade

13th Mississippi Infantry

17th Mississippi Infantry

18th Mississippi Infantry

21st Mississippi Infantry

Bryan’s Brigade

10th Georgia Infantry

50th Georgia Infantry

51st Georgia Infantry

53rd Georgia Infantry

Fitzhugh Lee’s Division (Cavalry)

Wickham’s Brigade

1st Virginia Cavalry

2nd Virginia Cavalry

3rd Virginia Cavalry

4th Virginia Cavalry

Rosser’s (Laurel) Brigade3

7th Virginia Cavalry

11th Virginia Cavalry

12th Virginia Cavalry

35th Virginia Cavalry Battalion (independent)

Payne’s Brigade

5th Virginia Cavalry

6th Virginia Cavalry

15th Virginia Cavalry

Artillery

Carter’s Battalion

Horse Artillery (seven batteries)

Independent partisan ranger units in theater

43rd Virginia Cavalry Battalion (Mosby’s Raiders)

McNeill’s Virginia Cavalry Company (McNeill’s Rangers)

Notes on Confederate forces

1. Sent to the valley on August 15, 1864.

2. Withdrawn September 14, 1864; ordered back, September 20.

3. Initially remained with the Army of Northern Virginia after Lee’s Division was sent to the valley. Ordered to the valley on September 20, 1864 from the Petersburg theater.

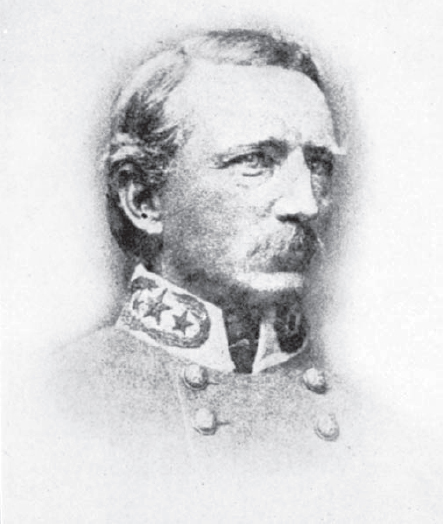

Major-General Joseph Kershaw commanded a division temporarily sent by Lee to reinforce the Army of the Valley. Kershaw’s Division was on its way back to Petersburg at the Third Battle of Winchester. It missed that battle as well as Fisher’s Hill, but rejoined Early in late September at Browns Gap (AC).