ON MARCH 5, 1840, a healthy, plump little girl was born to Hannah and Charles Jarvis Woolson in the riverside village of Claremont, New Hampshire. They named her Constance. Before they had time to adjust to the fact that yet another girl, their sixth, had been born to them, the older ones fell ill. Ominous red rashes spread across their faces, indicating scarlet fever. Connie, as they called her, was protected by her mother’s milk, and Georgiana and Emma, the oldest, recovered. But five-year-old Ann, four-year-old Gertrude, and two-year-old Julia did not. They died before Constance was a month old.

The family that remained would soon flee New Hampshire’s unforgiving winters and the sight of the three tiny headstones in the town cemetery next to the park. Hannah would never speak of the lost girls, but Constance knew that her birth had been overshadowed by their deaths.1 It is little wonder that for the rest of her life she would look over her shoulder, expecting her own or someone else’s end. In their letters, she and her family would often qualify their plans with the phrase “if I live.”

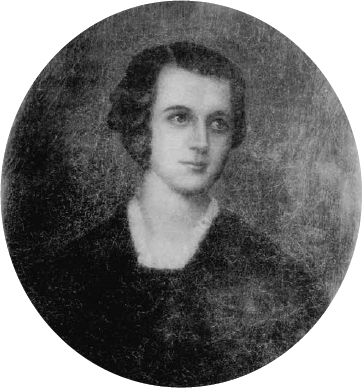

Hannah was broken by the sight of her girls’ empty beds and discarded playthings. Years later, one of her daughters would explain, “Mother nearly lost her reason. . . . Father often told us children that a ‘something’ went out of her that week, that was lost forever . . . so that we children did not know what Mother had really been except for a beautiful portrait which Father had had painted of her.”2 It shows a young Hannah with a thoughtful, almost dreamy look in her large, almond-shaped eyes. Constance would never know that calm, innocent gaze. She would know, instead, a worried, watchful mother’s eyes.

Many years later Hannah wrote rather coolly about her breakdown after the three little girls’ deaths. “My health was so much impaired that it was necessary to leave New England before another winter. We broke up housekeeping,” she wrote, using a common expression that conveys something of the devastation she felt. As Clara, the child who came after Constance, would one day write, “I have always thought the use of ‘breaking up’ a home so appropriate—to those who feel that it breaks up also a part of the heart that never heals!”3 This was certainly the case for Hannah, who had not only to pack up her books, silver, mahogany bed, and sewing table, but also to leave her darling little girls lying in the frozen New Hampshire earth.

Portrait of Hannah Cooper Pomeroy Woolson, before the deaths of her children.

(From Voices Out of the Past, vol. 1 of Five Generations (1785–1923))

This was the start of a pattern. When tragedy struck, when life became too hard, the Woolsons moved on. This response to grief became ingrained in their children, most of all Constance, who would spend the majority of her adult life on the move. The Woolsons’ home in Claremont was only the first of innumerable homes that would be broken up during her lifetime.

THE WOOLSONS IN CLAREMONT

That first home was a two-story, white, Greek Revival house that her father, Jarvis (he went by his middle name), had built across the street from his parents’ house. Claremont’s heyday would come and go with the Industrial Revolution. In the 1830s, the water power of the river was only beginning to be harnessed, and the town’s prospects remained dim. With the financial crisis of 1837, they all but evaporated. Hannah had no regrets about leaving the sleepy town. She detested the bitter winters and the cold New England stoicism, but Jarvis would always miss the hilly landscape of his youth.4

Constance’s parents had married on April 26, 1830, having met less than two months earlier at the wedding of Hannah’s best friend and cousin, Julia Campbell, and Jarvis’s best friend, Levi Turner, an up-and-coming lawyer. Turner had ties in Washington and spent tens of thousands of dollars each year speculating on western lands. Some of his air of promise must have rubbed off on his friend Jarvis, or perhaps Hannah was simply drawn to his sharp wit and affectionate ways, for Jarvis was not a lawyer, businessman, or speculator. His passion was journalism. A more capricious occupation would have been hard to find.

After briefly editing the Virginia Advocate in Charlottesville, where a New Englander opposed to slavery had little hope of success, Jarvis worked at the New England Palladium in Boston. But in 1833, having already three mouths besides his own to feed, he gave up his dream, moving his growing family back home and joining his father’s stove business. His love of the written word—exhibited early when he devoured David Hume’s six-volume History of England before age eleven—never waned, however. He would bequeath it to Constance, who was his pet and inherited his keen intellect and wit.5

After the death of his father in 1837, Jarvis took over the manufacture of the “Woolson Stoves,” his father’s invention and the most popular stoves in New England. Thomas Woolson left little other legacy. Constance would remember him as “a dreary useless man” who had given himself up to depression. Hannah described him as “a man of great intellectual ability, wonderful inventive powers, curious research into all strange subjects, but very peculiar in his manners, stern and, at times, morose, [making] his younger children very much afraid of him.” Much to Jarvis’s regret, his father did not come from a noble lineage. When Constance was young, her father spent years searching in vain for an aristocratic Woolson ancestor, finding only a Thomas Woolson who was sentenced in 1685 for peddling liquor without a license. Although she would carry a feeling of social inferiority with her throughout her life, Constance found as much humor as heartbreak in her father’s disappointment.6

Jarvis’s mother, Hannah Peabody Woolson, whose ancestors came over on the Planter in 1635, provided the noble ancestry and parental affection in the family. Jarvis took after her, becoming a loving father and grandfather. But Jarvis also inherited his mother’s deafness along with his father’s tendency toward depression. Unfortunately, Constance also inherited these traits. Jarvis would warn her against succumbing to the darkness that had engulfed his father, but there was little they could do about their acquired deafness. They could both hear as children and developed normal speech patterns, but in their late teenage or early adult years, their hearing began to degenerate and steadily receded throughout their lives, isolating them and exacerbating their depressive tendencies.

Jarvis’s worsening hearing may have prevented him from realizing his promise as a journalist or budding industrialist. Hannah’s cousin Richard Cooper wrote of him as early as 1831 that his deafness “incapacitates him from those pursuits, by which the majority of our young men rise to commerce and competency.”7 Jarvis never was as devoted to business as were his father, Levi Turner, and most of the men of his class. The only surviving portrait of him, in which he stands stiffly erect, staring directly into the camera with an icy look of confidence, is of a piece with the portraits of nineteenth-century military and business leaders. In life, however, he aspired to neither form of masculine accomplishment. Business was something he had settled for, having been barred from more intellectual pursuits.

Understandably, Constance never liked her father’s portrait. It conveyed nothing of his quick wit or lively sense of humor, both of which she also inherited from him. Contrary to the stern image it projects, he was in fact “something of a wag,” responding once to an inquiry about a prospective business associate with the lone fact that he was “a light-complexioned young man.” Described upon his death by the local paper as “a man of very domestic habits,” Jarvis’s primary devotion was to his family and to his books. His immense love for his daughters was unclouded by a desire for a boy. He claimed to possess “a strong admir[ation] of the fair sex” and “a pervading desire to render myself agreeable to the younger portion thereof.” When his seventh daughter, Clara, many years later became a mother, his affection had a new object in her baby girl. He wrote to Clara on one occasion, “ ‘Gampa’ wants to see Baby very bad indeed. He would walk ten miles to play with her half an hour.” For Constance, who took after her beloved father in appearance and personality, he was the ideal father.8

Charles Jarvis Woolson.

(From Voices Out of the Past, vol. 1 of Five Generations (1785–1923))

COOPERSTOWN AND THE COOPERS

The Woolsons’ first stop after they left Claremont in the wake of the three girls’ deaths was Hannah’s birthplace, Cooperstown, New York, on the shores of Lake Otsego. It had been founded in 1786 by her grandfather, the judge and speculator William Cooper. When he moved his family there, to a home still surrounded by wilderness, his wife, Elizabeth, sat in an heirloom Queen Anne chair and refused to budge, according to family legend. In response to his wife’s rebellion, William reportedly lifted the chair, with her in it, and placed them both in the wagon, signaling the caravan to begin its journey.9 This kind of stubborn willfulness cropped up periodically among the Cooper women, and Constance would inherit her fair share of it.

Among the seven Cooper children in that caravan were Hannah’s mother, Ann, and the future novelist James Fenimore Cooper, who would make Cooperstown and the region famous in his Leatherstocking novels. Ann and James were born five years apart and after 1820 were the only surviving siblings. James was away in New York and Europe during the years Ann raised her family in Cooperstown. Nonetheless, the bond between the families remained strong despite a rift in the 1820s when Ann and her husband, George Pomeroy, participated in the sale of many of the grand Cooper homes and initiated court proceedings to secure her share of the dwindling Cooper legacy. Unlike her mother, Hannah grew up in genteel poverty with a feeling of beleaguered family honor, which her uncle James redeemed in the early years of her marriage by becoming a famous author. When Constance was born, his prolific career was mostly behind him and he had returned to Cooperstown, restoring the family’s home, Otsego Hall, and with it the family’s pride.10

After the death of the three Woolson girls in Claremont, James urged his niece to come home to Cooperstown. He remembered how her little Annie, who had stayed there the preceding summer, “had made friends of us all,” writing to Hannah that “her quiet, affectionate, little ways are often present to my mind when I recall your loss.” He encouraged Hannah to turn for consolation to the Almighty, but in the meantime only the love of family and change of scenery could begin to break up the delirium of her grief. “[W]hile you will be just as near the spirits of the little ones here as there,” he wrote, “you will be more likely to see them as spirits, than when surrounded by objects familiarly connected with their brief lives. . . . Your friends will prove to you how much they feel for your privations, which are in some degree theirs, and the family tie will be strengthened by the sympathy you will meet.”11 Throughout Constance’s life, this tie between the Woolsons and Coopers, especially James’s daughters, would remain strong, no matter how far she roamed.

The greatest inheritance Constance received from the Cooper side of the family, however, was the middle name she shared with her great-uncle: Fenimore. While the Cooper name itself was fairly common and locally had fallen from its earlier preeminence, Fenimore retained its luster, which was only burnished by the novelist’s worldwide fame.12

The Cooper women bestowed on Constance less obvious, but no less important, influences. From them she inherited a contrary mixture of genteel convention and rebelliousness that would define her personality and make her the subtly powerful writer she was to become. Her grandmother, Ann Cooper Pomeroy, hewed closely to a conventional model of reserved womanhood. Her domestic life as Judge Cooper’s daughter and then as the wife of the affluent apothecary George Pomeroy fulfilled her every aspiration. She spent her long life in Cooperstown, serving as its chief charitable coordinator and caregiver, attending, it was said, virtually all of its births and deaths. Known as a homebody, Ann is said to have shut herself up in her house when the railroad first arrived in New York, declaring the whole state ruined by its invasion.13

Ann’s older sister, Hannah (namesake of Constance’s mother), was less content with her lot. A spirited young woman who enjoyed society and, in her words, “long, rough walks,” she bristled at her domestic and rural isolation in Cooperstown. The future prime minister of the French republic, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, was charmed by her during his 1795 visit to Cooperstown, extolling her as too refined for her uncultured surroundings. Although her brother James would immortalize her as a paragon of genteel young womanhood in his novel The Pioneers, she was in fact independent-minded and skeptical of the role she apparently played to perfection. Marriage seemed to her an intolerable crisis in a woman’s life: “It fixes her in a fate of all others the most happy or the most wretched,” she wrote in her commonplace book, recognizing the complete submission required of wives. She turned down many proposals, including one from future president William Henry Harrison. Hannah died suddenly at the age of twenty-three when, ignoring her oldest brother’s objections, she insisted on riding a new, extraordinarily spirited horse on a twenty-five-mile journey to visit friends. The roads were hilly and rough, and Hannah’s horse threw her after being spooked by a dog. She was killed instantly.14 A considerable portion of her skeptical and restless spirit would find its way into Constance.

As a young woman, Ann’s daughter Hannah Pomeroy Woolson possessed some of the daring of her namesake, but it was tempered by a deep attachment to home. Writing when she was almost twenty to her cousin William Cooper, then in Paris with their uncle James, she showed her bold side in a passage about her desire to reclaim for her family the dilapidated ancestral manor: “The present owner [of Otsego Hall] is a rich and invulnerable hearted old Bachelor. I had the vanity to think at one time, that I might become mistress of the mansion—but he never will be married—for if I failed to captivate him, is there any one that can do it[?] Oh certainly not! You may think I have a large portion of vanity in my composition, but really, you have no conception how I have improved in all that is beautiful within the last three or four years—and I do think I have but a humble opinion of my own merits.”15

But in spite of Hannah’s vivacity, she was as much of a homebody as her mother. In the same letter she admits that spending the coming winter in the gay society of New York would please her, but she preferred to stay in the relaxed atmosphere of Cooperstown where she felt more at home. She threatened to break out into verse on the subject of her birthplace, blaming heredity for her poetic tendencies.16 Still, while a young woman proud of her abilities, Hannah was nonetheless fearful of showing them off, an ambivalence she would pass along to her daughters.

Less than two years after writing this letter, Hannah married Jarvis. She gave birth within a year and then had a new baby every year or two thereafter for a decade. The duties of a wife and mother did not come easily to Hannah. She had never been taught the domestic arts; her mother had raised her to rely on servants for most household tasks. But in Claremont, the thrifty wives did all of their own baking, cooking, cleaning, sewing, knitting, and even carding and spinning of wool. Hannah would later write up humorous accounts for her granddaughters of her early mishaps as a housewife. She once mistakenly baked up forty-two perishable mincemeat pies instead of preserving the filling for use throughout the winter. The family got so tired of eating them that she instructed the kitchen girl to dispose of the leftovers after every meal, against the girl’s frugal impulses. More seriously, Hannah resented the way she saw wives treated in New England, inwardly rebelling against the “iron rule” of Claremont men who made their wives and daughters prepare breakfast and clean up by candlelight before sunrise.17

The Woolson home was presided over by a much gentler patriarch, but still the backbreaking tasks of nineteenth-century housekeeping had to be done. Although Hannah would later have the help of three Irish servants, she put to use the skills she learned from her sister-in-law in Claremont and was by all accounts a consummately domestic woman. She made sure that her own daughters were taught all of the skills they would need as wives and mothers, the only roles she ever imagined they would be called upon to fill.18

The gay girl who wrote to her cousin William faded considerably during the Claremont years as Hannah suffered the ill health that childbearing brought. After her third child was born she was so dangerously ill that the baby had to be sent away to a wet nurse. The doctor wasn’t sure Hannah would live. This trying period ended “what may be called the youth of our married life,” she later recollected. When the loss of the three girls to scarlet fever forever banished her youthful self, she did not retreat from her family, as many grieving mothers did, but was able to overcome her terrible sadness and be a caring, supportive presence in her remaining children’s lives. In the evenings, before the children went to bed, they gathered around her, finding a spot on her lap or on the arms of the rocking chair, and listened to her sing English and Scottish ballads, “the toe of her slipper just touching the floor to keep the chair rocking in time.”19

CLEVELAND

After a brief stay in Cooperstown, Hannah, Jarvis, and baby Connie joined the masses fleeing the depressed East for the promise-laden West. Georgiana and Emma, the two oldest daughters, were left behind with relatives. The heartbroken parents already had been preparing to move for some time. Jarvis’s friend Levi Turner had been a key player in the immense land grab that had been taming the upper Midwest frontier and populating it with New England outposts. Levi and others became wealthy seemingly overnight, benefiting from the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the completion of the Erie Canal.20

The financial depression of 1837 had been a major setback for Jarvis, but the plunge in western land values gave him his chance. That year, as the crisis reached its peak, he joined Turner and Hannah’s cousin Richard Cooper in search of western land. Jarvis was in for the long haul, rightly assuming that western expansion would continue despite the economic crisis. He made a fateful choice, allowing his “love of picturesque scenery,” as Constance later put it, to persuade him to buy lands in Michigan and Milwaukee over Chicago, whose muddy ugliness made him overlook its promising situation. Constance believed that if he had invested a tenth of that money in Chicago lands, he might have become a millionaire.21 As it was, Jarvis never made a fortune as a speculator, but his investments would provide a modest income well into Constance’s adulthood.

Jarvis was not content to simply speculate out west, however. The year before the Woolson girls’ deaths, he and Hannah had made an exploratory trip to see where they might want to live. They encountered friends and relatives at nearly every stop. Her cousins in Chicago took her out for a moonlit stroll through the city’s sand-covered streets and a sunny drive in the morning to see the vast, grassy prairie. She was impressed but felt this was no place to make a new home.22

Their return to the West in 1840 was a mission to find a more suitable residence. They bumped across rutted roads and sailed across Lake Erie, heading again toward that mythical land where the wide-open spaces provided plenty of opportunities to start afresh. When they reached Cleveland, Hannah is reported to have “expressed her first wish: ‘I like this place . . . Let’s stop travelling and stay.’ ” The young city had plenty of attractions, including beautiful views of Lake Erie and the fact that the city had been settled by New Englanders, many of whom they knew. Among them were the Turners, who welcomed the family into their home. That first winter was mild enough that Hannah decided they could stay for good. Jarvis retrieved Georgiana and Emma, and the Woolsons started over in a house on Rockwell Street, opposite the post office in the town’s center.23

The Cleveland they encountered in 1840 looked like a quaint New England village full of green-shuttered white cottages with neat flower gardens. Stores and small manufacturers lined Superior Street, one of the many dirt roads that were dusty in the sunshine and a muddy mess in the rain. As part of the “Western Reserve” of the Connecticut Land Company, Cleveland was a port town that would soon become a railroad hub, but for now shipping determined its fortunes. Lake Erie connected Cleveland to Buffalo and Detroit as well as to the interior of the Great Lakes region, which enterprising men would mine for iron and coal—and which Constance would one day mine for her earliest literary successes. Cleveland held few attractions for a budding writer, however. She would never set a story there. By the time she grew up and started to publish, the city had changed so much she hardly knew it.

Constance not only grew up in Cleveland; she grew up with it. During the years she lived there, from 1840 to the early 1870s, its population rose from 7,000 to 92,000, and it transformed into a bustling manufacturing city. During her youth the Cuyahoga River was bordered with sunny green meadows, and flocks of now-extinct passenger pigeons would occasionally block the sun for most of the day. Just as in Cooper’s The Pioneers, set decades earlier in Cooperstown, people climbed up to their roofs and, armed with sticks, struck the birds down for food or amusement. But such evidence of nature’s abundance would soon fade into memory, and, like her great-uncle, Woolson would fill her fiction with laments for the disappearance of the wilderness. What he had witnessed two generations earlier in the East was repeated in Cleveland. During her teenage years, she and a friend could row up the Cuyahoga River from her father’s stove foundry and stop for a picnic along the banks. But before she reached thirty, the river, whose pollution would help spark the twentieth-century environmental movement, caught fire for the first time, its banks crowded with smoke-belching iron mills and oil refineries.24

Yet throughout Constance’s youth, Cleveland was known as the “Forest City.” The residential east side of the city, where she lived, felt like a town surrounded by woods. Elm-lined Euclid Avenue was the city’s jewel. During Anthony Trollope’s 1861 visit, he lauded the expansive elms that bowed over its homes and sidewalks. Another foreign visitor likened the tree-lined street to “the nave and aisles of a huge cathedral.” The Woolsons lived there briefly in a large, two-storied stone house that would be torn down in 1865 to make room for a palatial estate. By then there was a streetcar running down the center of the avenue, which would become known as Millionaire’s Row, the affluence of its residents exceeding that of Fifth Avenue’s inhabitants in New York. The Woolsons, far from millionaires themselves, moved into a more modest home they called “Cheerful Corner” at Prospect and Perry, just off Euclid.25

As their home’s proximity to Euclid Avenue suggests, the Woolsons belonged to the city’s social elite. But, while the Woolson stove foundry was the first “of importance in Northern Ohio,” Jarvis suffered a series of setbacks, including the perfidy of his partner (a brother of Hannah’s, who absconded with thousands of dollars), and a fire that destroyed most of his business. He started over with a new partner, creating Woolson & Hitchcock, later Woolson, Hitchcock, & Carter. Still, he never prospered on the scale of the city’s other industrialists, such as John D. Rockefeller. Despite bringing the Woolson stove to a brand-new market, one that expanded exponentially during his lifetime, business was fickle. In 1851, Jarvis complained of persistent money problems, explaining, “I have been in such a constant struggle with the world ever since I came west, that I have never had a moment to spend for anything beyond my daily efforts to provide for the large number dependent upon me.”26 It wasn’t until the 1860s that Jarvis would be able to provide a comfortable, steady living for his family.

As the daughter of a father who forever felt like an exile from New England, Constance never felt like a “Daughter of Ohio.”27 But growing up among eastern transplants in Cleveland, as it became more and more diverse with Irish and German immigrants, she developed a broader patriotism. There was something about northern Ohio that would produce five U.S. presidents in the last thirty-two years of the nineteenth century and that would also make Woolson a thoroughly American writer, no matter how far away she moved from her Cleveland roots. Ohio was, at the time, the virtual center of the United States and would become a major economic and political force, if never a cultural one.

In Cleveland, Constance grew up among the men of the future—men who would make the coming era the “Gilded Age.” The brother of one of her best friends would become a major stakeholder in Standard Oil. Another friend would become one of Hawaii’s wealthiest sugar planters. Her nephew would build one of the most ostentatious mansions on Euclid Avenue with the fortune he earned in the coal industry.28 But the question of what role women would play in shaping the nation’s future remained to be answered.