WHEN JAMES’S essay “Miss Woolson” appeared in the February 12, 1887, issue of Harper’s Weekly, a full-page, folio-sized portrait of Woolson graced the cover of the magazine. It marked the culmination of years of worry over the idea of her portrait appearing in print. In Florence in 1883, Mrs. Howells had urged her to allow her brother, the sculptor Larkin Goldsmith Mead, to make a medallion portrait of her to complete his set of famous authors, comprising Howells, James, and Hay. Woolson expressed to both James and Hay her feelings on the subject: “I do not at all think that because a woman happens to write a little, her face, or her personality in any way, becomes the property of the public.”1

Mrs. Howells argued that “[w]hen the Harpers want your portrait, to put in the magazine—as of course they will—it will be all ready.” When Mead also suggested that portraits of American authors belonged on the Washington Monument, then nearing completion in the nation’s capital, Woolson felt as if she were living “a sort of night-mare.”2

In late 1885, when the Harpers first asked for her portrait, she turned to Hay: “As you may imagine, it is a pang to every nerve in my body, to be produced in public in that way; they say that I should not be able to suppress a likeness altogether, since there is a fancy at present for bringing out ‘series’ of ‘authors’ likenesses;’ & a photograph of some sort is sure to be obtained of everybody, somewhere; & the thing done whether the victim likes it or not. Therefore how much better to have a good likeness brought out in a proper place. Such is the argument.” Woolson knew the craze for writers’ photographs well because she had participated in it herself, as a consumer. Her collection included a portrait of Stedman cut from a magazine and a velvet triptych frame containing a poetical Hay, a smiling Howells, and a cynical James. But, she felt, “there’s no ‘proper place’ for an ugly woman!”3

When her portrait first appeared in Harper’s, in the March 1886 issue, she was happy to report that it looked nothing like her. Another representation that didn’t look much like her—more like a boy than a grown woman—was a bust created after an 1887 illness in which she had lost much of her hair. She wrote at length about it to her nephew: “Sam, do’nt you think you could lend me your nose? Richard Greenough, the Sculptor, who has been here [at Bellosguardo] lately (he lives in Rome) has formally asked permission to ‘do’ my head,—again reducing me to the embarrassed & vexed state of mind which the subject of ‘a likeness’ always produces. Why have’nt I a nose? It would be such a pleasure to decline modestly; & then be forced into consenting; & then have a lovely bust in marble to send you. Your [step]mother, now, might lend me her profile. I have declined Mr Greenough’s proposal—with thanks. I shall never sit to anyone—painter, sculptor, or photographer, again.”4 But the requests kept coming, and she was unable to hold them off.

Used to expressing her deepest feelings behind the mask of fiction, Woolson had erroneously believed that she could simply remain hidden. She desired fame for her writings but not celebrity for herself. It had come to her nonetheless. She was now, as a Cleveland paper remarked, “the world’s property.”5 She could, however, as the Harpers suggested, control her image, limiting, in effect, the public’s access to it. The portrait that accompanied James’s essay about her was a calculated attempt to satisfy the public’s cravings and thwart them at the same time. Rather than allow readers full access to her face, she deliberately turned away from the camera. Her body faces the viewer partially, but her head looks away. Her eyes are downcast, as if she has only reluctantly submitted to the intrusion. Her hair is pulled back into a braided coil. Her curls have been tamed, cut short and tightly framing her face. A neckband hides her throat, and a delicate lace cape conceals her bust. It is hard to imagine a more conservative portrait of the woman author. Look at me if you will, it seems to say to the viewer, but you will see only what I am prepared to reveal. Not coincidentally, the accompanying essay by Henry James sends substantially the same message.

Portrait of Woolson used for the etching in Harper’s Weekly, February 12, 1887, which took up the entire folio-sized cover of the paper.

(Correspondence and Journals of Henry James Jr. and Other Family Papers, MS Am 1094 [2245, f.58], by permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University)

JAMES’S “MISS WOOLSON”

In writing his essay “Miss Woolson,” James confronted the many complications of Woolson’s personal and public lives, not to mention his relationship with her.6 He would have to figure out a way to do her justice as the private woman he had come to know and as the author who had become the “world’s property.” It was also a test of their friendship, for he had picked up the critic’s pen, which, as Woolson knew well, could draw blood.

Author interviews and profiles had become incredibly popular in Britain and America, and it was inevitable that the Harpers would want one of the widely admired Woolson. Surely the Harpers asked James to write it because he had recently written two similar essays for Harper’s Weekly: one of his friend Howells and another of the artist Edwin A. Abbey, both accompanied by portraits.7 Considering how nearby Woolson was when he wrote the essay, she must have approved of the plan. Unfortunately, her feelings about the piece and the additional publicity it would thrust upon her have not survived. She probably accepted that someone would write a profile of her eventually and it was better to control the circumstances under which it was produced.

But could she? Although it was her friend who was writing the essay, she must also have feared his underlying disdain for women writers. He would, in fact, a few short weeks after penning the essay, write in his notebook venomously about the “scribbling, publishing, indiscreet, newspaperized American girl,” whose desire for publicity was “one of the most striking signs of our times.”8 Woolson’s withdrawal from public notoriety preserved her status as a proper woman, however. Surely she could trust James to treat her with more respect than he did the “newspaperized American girl.” But she still had cause for worry.

While his essay on Howells had begun quite conventionally with biographical details about the author, his essay on Woolson began much differently, indicating how foremost it was in his mind that he was writing about a woman. After a paragraph on the prominence of women in current literature, which says nothing about his proposed subject, he then erects a protective screen around her:

The work of Miss Constance Fenimore Woolson is an excellent example of the way the door stands open between the personal life of American women and the immeasurable world of print. . . . [Her work] breathes a spirit singularly and essentially conservative—the sort of spirit which . . . seem[s] most to oppose itself to the introduction into the feminine lot of new and complicating elements. . . . [I]t would never occur to her to lend her voice for the plea for further exposure—for a revolution which should place her sex in the thick of the struggle for power. Such is the turn of mind of the author . . . and if it has not prevented her from writing books, from competing for the literary laurel, this is proof of the strength of the current which to-day carries both sexes alike to that mode of expression.

At the end of the essay, he reiterates that her works “all have the stamp . . . of the author’s conservative feeling, the implication that for her the life of a woman is essentially an affair of private relations.”9

On the one hand, James was trying to preserve her privacy by telling readers she desired no “exposure.” On the other, he thrust her into the fray of “competing [with men] for the literary laurel,” hardly a “conservative” act. James seems to be taking his cues from Woolson herself, seeking a compromise between the private woman he knew and the artist her writings had revealed her to be. It was a conundrum neither could easily solve. His essay suggests he supported her determination to maintain a conservative identity as a woman while she also adopted a fairly radical conception of herself as a serious author. In fact, the only way she could make the assertiveness of her bid for recognition palatable was to hide it behind an image of herself as a private, traditional woman.

Under pressure to include some biographical details about his subject, James mentions a few, pretending to be simply an interested reader rather than someone who actually knows her. In his essay on Howells, he hadn’t mentioned their relationship either because he wanted to distance himself from his friend’s critical views, namely an adulatory essay on James that had drawn intense criticism.10 James also had to distance himself from Woolson, but for different reasons. Their friendship was known to a few friends and relations but it was not something either wanted publicized. To avoid the scandal that could ensue if their closeness became the topic of public discussion, James kept “Miss Woolson” at arm’s length.

Applying his own dictum that “[t]he artist’s life is his work, and this is the place to observe him,” most of the essay concerns itself with her writings. Considering that most criticism on women writers focused inordinately on the author’s personal life, his focus on her work suggests his great respect. “Miss Woolson” does, in fact, contain some very high praise. He found her southern stories “the fruit of a remarkable minuteness of observation and tenderness of feeling” and thought East Angels “represent[ed] a long stride in her talent,” predicting that “if her talent is capable, in another novel, of making an advance equal to that represented by this work in relation to its predecessors, she will have made a substantial contribution to our new literature.”11

Perhaps most important to Woolson, he was loyal to her in his lengthy defense of her portrayal of Margaret Thorne in East Angels. Some small criticisms creep in, and although he could be accused of some “enigmatic doublespeak,” he was much kinder to her than he was to Howells. James came close to the heart of her work (and life) when he noted that she was “fond of irretrievable personal failures, of people who have had to give up even the memory of happiness, who love and suffer in silence, and minister in secret to those who look over their heads. She is interested in secret histories, in the ‘inner life’ of the weak, the superfluous, the disappointed, the bereaved, the unmarried.”12

Woolson must have been pleased with the essay. James had protected her privacy, taken her side against Howells, and given her some of the highest praise he had granted any woman writer.

UNDER THE SAME ROOF

In the early spring of 1887, not long after the publication of “Miss Woolson,” James fell seriously ill in Venice. After much worry over his strange symptoms, he discovered that he had jaundice. Woolson was alarmed and wrote him letters of consolation and advice. She worried she had intruded herself, but he sent her a message through Boott: “Tell Fenimore I forgive her—but only an angel would. She will understand.” As James’s sister Alice explained to her sister-in-law back in the United States, “I hear from him & from an outside source [Woolson] that the attack is a light one.” But Woolson must have known how serious it was. James would later say that his health “was more acutely deranged in Venice than it had been since my youthful years.” Alice was relieved to learn that he had “Miss Woolson in the background at Bellosguardo upon whom he is going to fall back when he is able to travel to Florence.”13 Woolson had offered him the apartment below hers, where he could recuperate far from the cold air of Venice and avoid the social obligations of Florence.

James arrived in the middle of April. Dr. Baldwin, Woolson’s friend and doctor, met him at the train station and escorted him to Bellosguardo. James’s health and good spirits revived quickly. He planned to stay until the first of June so that he could fully recover. Unlike his previous stay, this time he was Woolson’s guest. He planned to “lead a life of seclusion and finish some work,” he told one friend whose lunch invitation he declined. James was busy writing “The Aspern Papers,” a story about an eager biographer who insinuates himself into the lives of two unmarried women—an elderly aunt and her middle-aged niece—in Venice. The narrator hopes the aunt will die and leave him her love letters from a famous writer whose memory he has cultivated. James’s return to the Villa Brichieri may have recalled to him the voracious appetite of the public for authors’ lives, an appetite he had attempted to both satisfy and thwart in “Miss Woolson.” The story’s theme of a secret relationship, the evidence of which is burned in the end, may also have been inspired by the deepening friendship between the two writers, which they increasingly desired to keep to themselves.14

During James’s six-week stay, he and Woolson would determine once and for all the nature of their relationship. Were they companions, bachelor and spinster, who could conceivably take the next step toward romance? Or were they writers, that breed apart, who could live outside of the conventional arrangements between men and women? Woolson may have wanted to remain a “proper woman,” but her friendship with James was charting new territory that her mother and sisters would not have dared to enter. And he was certainly as conservative as she in his desire to conceal his private life.

Only a few people knew of their living arrangements—Boott, the Duvenecks, Baldwin, and possibly Alice. James wrote of his new situation to his sister-in-law but made no mention of Woolson. Woolson’s letters to her nephew, Sam, make no reference to her tenant. Instead, she focuses on her contentment with her new home. “I am so happy here, Sam, that . . . it is pathetic—almost. The old Auntie enjoys, like a child, her own cups & saucers, & chairs & tables. The view is a constant Paradise to me.” James, below her, wrote the very next day in similar tones. “I sit here making love to Italy,” he told a friend in London. “At this divine moment she is perfectly irresistible.” He attributed his bliss to his surroundings, the “supercelestial” Villa Brichieri, and the new flowers of spring. “There is nothing personal or literary in the air,” he insisted. “The only intelligent person in the place [Florence] is [the writer] Violet Paget.” To Katherine de Kay Bronson, a widow and close friend of the late Robert Browning, who lived in Venice, he casually mentioned that he had met one of her kinswomen who “appeared here yesterday punctually to call on my neighbor Miss Woolson, on whom I was also calling.”15

Although they were living under the same roof, they were in separate apartments with separate entrances, so their afternoons together were essentially visits. His account to his brother William indicates that he wrote all day in his quiet rooms and then went down to Florence every evening for dinner.16 To William’s wife, Alice, he wrote that he had his own cook. However, he and Woolson must have shared Angelo, who surely prepared meals for two when James was in the house. Undoubtedly they had many meals together, as they had the previous December when he was living nearby.

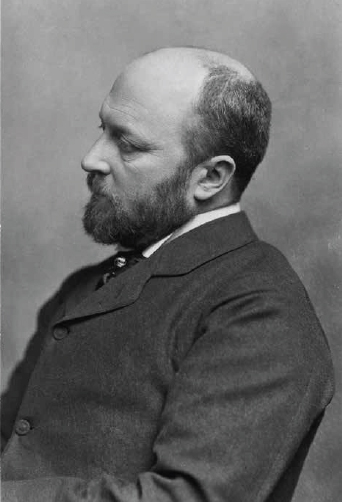

Henry James stayed in the downstairs apartment of Woolson’s villa for six weeks in 1887, visiting with her daily. Photograph from 1890.

(Correspondence and Journals of Henry James Jr and Other Family Papers, MS Am 1094 [2246, f.33], by permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University)

The two were hardly alone on their hilltop, however. Francis, Lizzie, Frank, and the baby were again in residence at the Villa Castellani. A constant stream of visitors from Florence kept Woolson very busy, as she complained in letters. She had limited social calls to one day a week and did not return them, assuming that people came as much for recreation and the view as to see her. In April and May, while James was living downstairs, every American in Italy seemed to be in town for the series of fetes leading up to the unveiling of the Duomo’s new façade.

As the event neared, the city was bursting with excitement about “the processions, the fireworks & illuminations, regattas, tournaments, races, etc.” Woolson thought that up on her hill she could stay above the fray, but her position perched above the city proved to be the best place to watch the fireworks. For five evenings in a row she had guests to entertain. As they were English, she had to serve tea and discuss the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, their dearest project. Woolson felt as if she were the abused animal in the scenario, especially when they waited in vain night after night for the promised pyrotechnics. Finally, the night of the illumination arrived. All of Florence “blazed with light,” and “the tower of the Palazzo Vecchio, the Dome of the Cathedral, & all the spires & campaniles were outlined in lines of glittering stars.” The hills all around glowed with bonfires.17

Sitting outside during the cool nights took its toll, however, and soon Woolson fell ill. Dr. Baldwin made a house call, and James repaid her kindness by helping to care for her. This isn’t the picture usually drawn of their friendship, in which her devotion to him is often portrayed as one-sided. However, Woolson later told the English-American writer Frances Hodgson Burnett, the author of Little Lord Fauntleroy, about James’s “great kindness and attention to her when she was ill.” When Burnett later met him, she “found him all that [Woolson] described, most gentlemanly, kind and attentive—a charming man, indeed.”18 The two friends probably never knew of Burnett’s disclosure of their intimacy to a newspaper reporter in Richfield, New York. They would have been horrified if they had.

Beyond such glimpses, however, their friendship during these years is a virtual blank. Not only did they conceal their proximity to others, they also at some point, probably around this time, made a pact to burn their letters to each other. Some have assumed that James was eager to destroy the secrets he shared with her and that he may have even desired to erase her from his life. Many have also suspected that James and Woolson wished to thwart future biographers. But just as likely, the agreement was intended to maintain their privacy in the present. Letters were often read aloud to friends and family or sent on to others for their enjoyment. James’s and Woolson’s agreement would make their correspondence a private affair. He made no such agreement with anyone else—not even the two other women who were among his closest friends over the years, Grace Norton and Edith Wharton. When Norton once chastised him for reading portions of her letters aloud to others, he responded, “It is indeed, I think, of the very essence of a good letter to be shown,—it is wasted if it be kept for one.” By the same token, she was free to share his letters with others.19 While Norton could not convince him of the necessity of keeping their correspondence an intimate affair, Woolson could and did.

On her side, the pact to burn letters was not unique, so it was probably her idea. She had a similar arrangement with her sister Clara, whose daughter suggested many years later that the two writers’ agreement to destroy their correspondence was the result of their wish to “write freely.” Clara once noted, “Connie always wrote me when she was going to use me as a ‘safety valve,’ and pour out to me what at that moment was overpowering her.” Constance, who guarded herself so carefully, seems to have grown comfortable revealing private aspects of herself to Henry. The mask she wore for the rest of the world had slipped. “Though I pass for a constantly-smiling, ever-pleased person, [m]y smile is the basest hypocrisy,” she had earlier told him.20 What a relief it was to be able to be herself, as her character Margaret Harold never could.

The Constance revealed in the letters that do survive could be frustrated at times and even admit to feeling depressed, but she was mostly chatty, witty, and earnestly observant. It is only from her niece Clare that we know another side of her. As Clare later wrote, “My aunt had a passionate and dramatic nature, and a high temper.” This was the Constance who hid behind the smiling façade. Clare continued, “But she was extremely gracious and a wonderful friend. I don’t think that Cousin Henry had those characteristics—he had intellect, humour and an extraordinarily fine perception of other people’s feelings and ideas.” Their personalities complemented each other. Henry offered her his comprehension, which she returned, along with her devotion.21

What the two writers felt for each other was undoubtedly a kind of love, but one not sanctioned by their era. They had certainly been very fond of each other from the beginning. But after their frequent meetings in London in 1883 and James’s subsequent visits to her elsewhere in England, the affinity between them had flourished. In Italy, not only did they enjoy each other’s company, but they also discovered that they could rely on each other at their most vulnerable times, when they were ill, essentially taking the place of faraway relatives. After living together at the Villa Brichieri, Constance began to call him “Harry.”22 Only his family and old friends from America called him that. Perhaps he also started calling her “Connie,” as all of her family did.

During this time they were also drawn together by their mutual friends Francis Boott and his daughter, Lizzie. While Henry was staying with Constance, he too became a part of the quasi-family she had joined. Her great affection for Francis undoubtedly lessened Henry’s fears that she may have been growing exclusively attached to him. He must have felt more comfortable accepting her hospitality and allowing her to approach him more closely now that it was clear her affection was not for him alone. He could show an even greater interest in her without fearing that she might misinterpret his attention as romantic. Whether or not she ever knew that James was sexually attracted to men, as most critics today believe he was, she certainly understood the boundaries of their relationship.

Although Henry was closer to Constance than anyone else outside of his family, he still raised emotional barriers. He always put his writing above his relationships. His amanuensis, Theodora Bosanquet, would write much later, “He loved his friends, but he was condemned by the law of his being to keep clear of any really entangling net of human affection and exaction. His contacts had to be subordinate, or indeed ancillary, to the vocation he had followed with a single passion.” In the coming years, James would write a series of stories that solidified that commitment as he also struggled to make sense of his intimacy with Woolson. She would accept it more easily for what it was—a bond of minds and hearts. The outer limits of their alliance were taking shape but perhaps not yet set. They would arrange visits whenever they could, but they would not marry, they would not live in the same apartment, and they would not have a physical relationship. But there was also a lot of gray area for the two dedicated writers to navigate up to those limits. Woolson must have seen what Edith Wharton would later recognize: he was “a solitary who could not live alone.” Wharton perceived “a deep central loneliness” as well as “a deep craving for recognition” in him.23 Not coincidentally, Woolson possessed those qualities as well. She and James were drawn to each other as two isolated, ambitious souls who feared being completely alone in the world. They both knew there was someone within reach (if only by letter or occasionally by train) who understood their need for connection and solitude.

James recognized that Woolson was as devoted to her work as he was to his. Living below her apartment, he was aware of her steady work habits and admired her for them. Sometime in 1887 he gave her a volume of Shelley’s poetry inscribed to “Constance Woolson / from her friend and confrère.” With the French word confrère—colleague or comrade, the root of which is Latin for “brother”—he acknowledged her as a companion in the writing life and as a would-be sibling. Theirs was a chosen kinship. They both knew by now that the other would never marry. Marriage was, however, the only model they had for close relationships between men and women, and families were defined by blood. So they had to forge a new way to think about their intimacy. In later years Clare referred to him as “Cousin Henry,” signifying that he was viewed as a member of the family.24 To think of him as an uncle would have been to insinuate a marital relationship with her aunt. “Cousin,” however, kept the connection familial but vague.

Constance and Henry’s time together at Bellosguardo ended in the middle of May, earlier than James had at first projected. Alice needed him back in London now that Katharine Loring was preparing to return to her family. Much as Alice and Katharine had created an extrafamilial, extramarital bond that was as close as, if not closer, than those they shared with their blood relatives, so too had Henry and Constance. Although they would never again live under the same roof, their relationship would remain strong for the rest of her life.

BETRAYING MISS WOOLSON

Despite their greater intimacy, however, the tensions between the two as writers remained. They resurfaced when, after James’s return to England, he put together a new volume of critical essays, titled Partial Portraits, for which he decided to revise “Miss Woolson.” He cut out the biographical paragraph (perhaps at her request) but also added some new criticisms of East Angels. Woolson always said she wanted candid assessments of her work, but these were hardly the constructive kind.

In his revised version of the essay, which would appear in May 1888, James portrays Woolson as merely a woman writer, who is inherently incapable of writing to the same standard as men. In the new version, he opens with a fuller discussion of the prevalence of women writers: “Flooded as we have been in these latter days with copious discussion as to the admission of women to various offices, colleges, functions, and privileges, singularly little attention has been paid, by themselves at least, to the fact that in one highly important department of human affairs their cause is already gained—gained in such a way as to deprive them largely of their ground, formerly so substantial, for complaining of the intolerance of man.” Woolson’s story “At the Château of Corrine” certainly had complained of just that. (The story was finally published in October 1887.) To her, men’s contempt toward women such as herself had not dissipated, merely gone underground. As Ford tells Katharine Winthrop, men only pretended to appreciate women writers. James insisted, in a new passage added to the essay, “In America, in England, today, it is no longer a question of their admission into the world of literature: they are there in force; they have been admitted, with all the honors, on a perfectly equal footing. In America, at least, one feels tempted at moments to exclaim that they are in themselves the world of literature.”25 Surely he overstates his case.

The real betrayal of his friend (much more serious than calling her “conservative” or belittling her portrayal of men’s continued intolerance toward women writers) came in a new paragraph, in which he now delineated East Angels’ “defects.” The most serious was a direct result of the author’s gender. “[I]t is characteristic of the feminine, as distinguished from the masculine hand,” James wrote, “that in any portrait of a corner of human affairs the particular effect produced in East Angels, that of what we used to call the love-story, will be the dominant one. . . . In novels by men other things are there to a greater or less degree, [but] in women’s, when they are of the category to which I allude, there are not but that one.”26 While love was not a particularly important subject for men, women seemed incapable of writing about anything else. James’s criticism brings to mind that of John Ford toward Katherine Winthrop’s poetry. Whether or not James read the story, he fulfilled Woolson’s prediction that underneath the polite criticism lingered a deep-seated distaste for women acting on their literary ambitions.

Having worked so long for acceptance by male critics and peers, Woolson was probably disappointed but not surprised by James’s condescension. But considering that East Angels was in part a response to The Portrait of a Lady—which is almost entirely preoccupied with the question of marriage, although less so with love (for which she had criticized him)—she must have been stung by his comments. She had specifically faulted him for not showing his characters in love. Now he criticized her for showing little else, an unfair assessment, really, given the novel’s considerable attention to its Florida setting and analysis of character and social relations. The love story is never the sole theme of her novels.

Woolson would have her revenge, but privately. She had recently written in her notebooks, “If a man is a critic like Lang, or Birrell, he will never appreciate or care for a love story. . . . But in spite of these gentlemen the great fact remains that nine-tenths of the great mass of readers care only for the love story.” Sometime around the time of James’s Partial Portraits essay, she also wrote out the idea for a tale, never written, of the female writer’s victory over the pompous male critics, not unlike the James-like characters in some of her stories:

The case of Mrs. B., unable to read any tongue but her own, and having read herself but very little even in her own language—but who yet can produce works that touch all hearts—carry people away. A man of real critical talent (like [Matthew] Arnold) and the widest culture, thrown with such a gifted ignoramus. His wonder. At first, he simply despises her. But when he sees and hears the great admiration her works excite, he is stupefied. He follows her about, and listens to her. She betrays her ignorance every time she opens her mouth. Yet she produces the creations that are utterly beyond him. Possibly he tries—having made vast preparations. And while he is studying and preparing, she has done it!27

Woolson was no “ignoramus,” although she felt that her education had inadequately prepared her to compete with the likes of Arnold or James. Her fantasy of the success of Mrs. B. stupefying the male critics certainly had a personal element to it. She also understood that the fact of her success with the public remained a thorn in James’s side. What she didn’t add to her idea for this story is the envious male critic disparaging the woman writer’s works in print, reasserting his authority over the field of literature, as James had done.

After Woolson’s death, James would read her notebooks, even borrowing a story idea from them.28 So he likely read about Mrs. B. Did he see a shadow of himself and Woolson there? If so, her triumph came too late. Still, she must have taken pride in the fact that she was the only living American author (and the only American besides Emerson) included in Partial Portraits. Howells, her chief adversary, was left out entirely.