SOMETIME IN the months after Jarvis Woolson’s death, Constance walked beneath the overhanging elms along Euclid Avenue on her way downtown to the Herald newspaper offices on Bank Street. A portfolio was tucked under her arm. Inside were a historical essay on Mackinac Island, a reminiscence about a visit to Zoar, and a short story about a doomed Indian summer romance at a Zoar-like retreat. Each of these pieces contained a little bit of her father and the trips they took together. On every page were oblique tributes to him, evidence of the gifts he had given her over the years: a historian’s reverence for the past, a romantic’s adoration of nature unspoiled, and a realist’s regard for “strong wood-cuts” over “nondescript scenery.”1 She would show the portfolio to the group of men waiting for her in the Herald offices, and they would decide if she could make of herself a writer.

Until now she had shared her writings with only a few carefully chosen friends. They had urged her to exercise her literary talent and even convinced her to allow the Herald to publish, anonymously, some of the letters she had written to them while on her summer excursions. But she was alarmed at the idea of seeing her name in print. Fear of failure and of publicity had held her back. Her shyness and low opinion of herself had combined with the lingering feeling that a woman should not dare that way. According to one of Connie’s cousins, her father had encouraged her writing while he was still alive, and she deeply regretted that he did not live to see her begin her career. However, without his death and the loss of his income, it is questionable whether she would ever have braved public exposure. In fact, it may have been a fear of disappointing him, should she fail, that prevented her from pursuing publication. Now her friends, including her brother-in-law and his father, part owners of the Herald and executors of her father’s estate, told her she essentially had no choice. She had to overcome her squeamishness about appearing in print for her own and her mother’s sake.2

A SERIOUS QUESTION

After Jarvis’s death, all his heirs could do was sell his business and some of the land on which the stove foundry was situated for $12,000. There were also the Wisconsin lands, which would continue to earn modestly for many years. But there must also have been debts, for the end result was that Constance and Hannah no longer had enough money to live without constant anxiety. Constance bore the full weight of their financial worries. Charlie had barely left the nest and wasn’t making much money. Clara and her husband could help some, but they were not wealthy. The Mathers were, however, and they offered assistance, but Constance would not accept it. At the age of twenty-nine, she was determined to stand on her own.3

Thus Constance joined the army of so-called surplus women, who had since the war outnumbered men in many states and had to support themselves. According to an article in Harper’s magazine, how single women could support themselves had become “a most serious question to society.” The typically female occupations of governess, teacher, and seamstress were overcrowded. Constance was certainly well trained for teaching, and her old teacher Linda Guilford, now principal of the Cleveland Academy, would surely have hired her. However, female teachers earned on average only $659 a year, and the uniformly overworked and underpaid schoolteachers in Woolson’s fiction suggest she had little appetite for the profession.4

Writing was much more appealing, but also more uncertain. It could be done at home, and the magazines were filled with the names of women who seemed to have made their fortunes—or at least a decent living—at it. However, as the Harper’s article also pointed out, most who attempted it failed to earn any support at all. Indeed, the literary and journalistic fields had been so glutted with aspiring female writers that the editor of Harper’s in 1867, replying to someone signing herself “A Weak-Minded Woman,” had warned the multitudes of women longing to see their names in print to put down their pens. Constance was an avid reader of literary periodicals, including Harper’s, and very likely read this column, as well as the response from “Another Weak-Minded Woman,” who claimed to have been seized by the “furore scribendi” to disastrous results, including the neglect of her family. This erstwhile aspirant now took it upon herself to “warn others how straight is the gate and narrow is the way to authorship, and how few there be that find it.” She counseled, “Bury pen and paper at once. . . . That way lies madness.” The successful writer Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, who had just published her runaway bestseller The Gates Ajar, was hardly more encouraging in her contribution to the discussion, titled “What Shall They Do?” She was grieved “to see in what crowds the women, married and unmarried, flock to the gates of authorship” to be “turn[ed] away in great sad groups, shut out.”5

In spite of the miserable chances for a young woman from Cleveland, Ohio, to make a name for herself as a writer, it seemed like Constance’s best chance. One reason why was the men waiting for her at the Herald offices on Bank Street: family friend George A. Benedict, part owner of the newspaper, and his son and partner, George S. Benedict, Clara’s husband. Also in attendance was John H. A. Bone, who ran the literary department of the paper and was an experienced author, having published in the Atlantic Monthly and elsewhere. The men looked over her portfolio and gave her their verdict: they decided she should make a go of it. Bone knew many of the literary men she would need to approach, including the Harpers, who published a monthly and two weekly magazines, and Oliver Bunce, an editor at Appletons’ Journal. Bone would write her letters of introduction to each of them. The “weak-minded” women yearning to become authors would have given their eyeteeth for such connections.6

Another auspicious circumstance that made Woolson’s entrance into the literary world a fait accompli was her middle name. “Fenimore,” the name Constance shared with America’s first famous novelist, was a marketable commodity, and Bone was eager to capitalize on it. He used her full name in his letters of introduction and suggested that when she talked with prospective editors she mention being a grandniece of James Fenimore Cooper. She was unsure of the propriety of leaning on her Cooper connection and was casting about for a pseudonym. Bone was adamant, however, and she was outnumbered; the three men who held her future in their hands convinced her to brave full exposure. There would be no turning back.7

George S. Benedict was soon on his way to New York on business. He brought Constance with him, armed with her portfolio and Bone’s letters of introduction. They first visited the Harper & Brothers office on Franklin Square. As she sat in the dusty, cigar-ash-covered office of the editor, Henry Mills Alden, noticing the shelves teeming with stacks of unpublished manuscripts, her heart was in her throat. Although Alden had turned away many a novice author, Constance fared better than she could have hoped. The name “Fenimore” drew his attention, and he was impressed to learn of her connection to the author of The Last of the Mohicans. He said he and his colleagues would look at her stories and asked her to return the next day for their decision. When she came back, not only did they want the stories she had given Alden, but they also wanted her to send them everything she wrote. She gratefully agreed. During that first trip to New York, she also met with Bunce at Appletons’, who was disappointed the Harpers had gotten her first. He asked her to send him whatever she felt free to submit elsewhere.8

From the beginning, she produced more than Harper’s could publish. Woolson’s first two signed publications appeared in July 1870: “The Happy Valley,” about Zoar, in Harper’s, and “The Fairy Island,” about Mackinac, in Putnam’s, a New York magazine to which her great-uncle and her cousin, George Pomeroy Keese, had contributed in the 1850s. Not exactly travel essays, these were whimsical tributes to her two favorite places, both still hidden away from the bustle of the modern world. For the rest of her career she would write about such places, often having to exaggerate their remoteness as the civilized world encroached on them. Four months later, her first short story, “An October Idyl,” appeared in Harper’s. It was oddly unconventional in its portrayal of an illicit flirtation that could not be consummated. Set in a remote Zoar-like village during an Indian summer, the story was the first of many in which Woolson would portray lovers who have found each other beyond the boundaries of an oppressive social world but must resign themselves to lives of duty, “returning to [their] stations in the hard world.” After the story’s publication, Arabella sent her some criticism, to which Constance responded defensively: “ ‘The October Idyll’ was wordy, but I am only feeling my way, now. I shall do better in time, but I never cease to wonder at my success. If you think it is easy to advance, even so short a distance as I have, just try it.”9

Just as she was launching her career, she and her mother spent the summer in Cooperstown, giving Constance an opportunity to reflect on what she had inherited with her famous middle name. Although her first pieces had appeared under “C. F. Woolson” and “Constance F. Woolson,” she soon changed her mind about suppressing the “Fenimore” and even decided to adopt the pseudonym “Constance Fenimore” for a tribute to Cooperstown and her uncle in Harper’s titled “A Haunted Lake.” In the essay she described how “memories of the past” lingered over Otsego Lake and the wild, wooded hills around it. She felt more than a little haunted by the legacy Cooper had left behind: “The air is filled with an unseen presence, and a spirit moves upon the face of the deep. A master mind has hallowed the scene; and as we linger on the pebbly beach the echoes seem to repeat his name over our heads and the waters to murmur at our feet.” Although she was drawn to the pioneers and wild frontiers Cooper had so famously portrayed, she was not sure such a heritage was accessible to her as a woman who had grown up in a domesticated Midwest transformed into an industrial center. Nonetheless, she found a model for herself in the kind of writer he had been: “Those authors who write from within, and coin their own brains into words, may go dreamily through the world, their eyes fixed upon vacancy, . . . but the man who takes mankind for his subject, the man who writes to benefit and interest his race, is quick-witted and sharp-sighted, drawing upon his own observations of every-day life.” However romantic a writer Cooper may seem to us today, to Woolson he provided a model of the writer interested in keenly observing the “literal truth.” In him she found a form of realism that was “far more fascinating . . . than the wildest flights of fancy.”10

Just as this piece was published, however, Constance had second thoughts about riding on her great-uncle’s coattails, deciding to retract her use of “Constance Fenimore” in favor of her “true signature.”11 Yet she still couldn’t decide what that should be. In the coming years, she would continue to vacillate between Constance F. Woolson and her full name.

LET LOOSE

Most women writers in the nineteenth century wrote from the vantage point of their homes. Woolson was different. Having trained her eye, as her father had encouraged her, to look out at the world, the impulse to write drove her away from home. Living in Cleveland, she would never amount to much, she believed. She needed a wider field to make her observations of life worth recording. As a single woman, however, her options for roaming were few.

Her brother, Charlie, now nearly twenty-four, was in an entirely different situation. The world lay spread out before him like a smorgasbord. He had only to choose his destination. When he came for a visit to Cooperstown that summer of 1870, he announced that he had been given a position at A. T. Stewart’s, one of the largest department stores in the heart of Manhattan’s fashionable shopping district. Here was Connie’s chance; she could follow her younger brother out into the world. It was decided that as winter approached Hannah would return to Cleveland to live with Clara and George, and Constance would follow Charlie to New York.12 While he was going there to become a clerk and start his upward climb (as Zeph had done many years before), her prospects were less certain. Moving to New York was simultaneously a step away from her identity as a daughter and a step toward a new identity as a writer that she barely knew how to imagine.

The plan was for Constance to write letters about New York for publication in the Herald back in Cleveland. Newspaper writing has always been an important source of income and training for American writers. Woolson’s foray into that field would be short, but it was instrumental in helping her develop the critical eye and authoritative voice that would serve her well in her later work. Travel letters were a popular feature in American newspapers throughout the nineteenth century, and many of them were written by women. But it was the opinion columnist—the first was Fanny Fern in the 1850s—who would initiate a new tone for women journalists. During the postwar period witty, sometimes caustic, writers such as Gail Hamilton and Kate Field set the standard. Constance likely knew Field’s work, as it often appeared in the New York Tribune. Field was the consummate modern woman, roaming widely and living by her pen. Henry James would use her in The Portrait of a Lady as the basis for his intrepid female reporter, Henrietta Stackpole, who “smell[s] of the Future—it almost knocks one down!”13

Constance would try on a similar literary persona, publishing at least five letters in the Herald under headings such as “Gotham. What a Woman Sees and Says,” and “Gotham. A Bit of Bright Womanly Gossip.” They are long, witty, sometimes chatty, and invariably opinionated. Hiding behind the anonymity of “Our Special Correspondent,” she could poke fun at the men’s “Manhattan uniform”—incomplete without a “variously shaded brown appendage curving over the upper lip and ferociously waxed at the end”—or marvel at the abundance of fur on the ladies—one “immediately withdraws all he has ever said against our new acquisition, Alaska, where every four-legged animal in the land must have been sacrificed last summer to supply the demand for ‘Alaska Sable’ now raging in the metropolis.” At the venerable St. Paul’s, she found fodder for her pen in a name on one of the old memorial tablets: “ ‘Rip Van Dam!’ Did anyone ever hear of a more astonishing title? It is of no use to tell that he was a staid, dignified burgher of pious and portly presence. His name is against it, and we will not believe it. No one but a regular rip-and-tear sort of fellow, a very dare-devil, a roistering, rollicking chap, would ever have borne such a name as those three significant mono-syllables, ‘Rip Van Dam!’ ”14

Constance found her subjects primarily in the posh part of the city. Her boardinghouse at Broadway and Thirty-Second Street, where Charlie probably also lived, was only a block away from Fifth Avenue and around the corner from the mansions of the Astors, Stewarts, and other upper-crust New Yorkers. Flora Payne Whitney was living comfortably in the new brownstone her father had built for her and her new husband at 74 Park Avenue, three blocks away, where they were rapidly climbing their way up into Mrs. Astor’s Four Hundred. Constance was never comfortable around such wealth or ostentation. Walking along Broadway or Fifth Avenue, noting the diamonds, the elaborately braided hair, and long, close-fitting gloves, Constance knew she could never “deceive the cool eye of a city lady who reads you like a book, stamps you as countrified and lets you go.”15

The real New York she had come to see was to be found in its cultural offerings, reviews of which filled her Herald letters. Free of responsibilities for others and free of provincial Cleveland, she was now able to immerse herself in the finest art, music, and theater on offer. She wrote to Arabella that she felt “just like a prisoner let loose.” She worried at her excessive fondness for the city’s attractions but nonetheless “revel[ed] in the superb orchestras, magnificent architecture, beautiful faces and delicious voices.” She felt as if she were at the center of the universe, where “stars of every magnitude have come to shine in the New World.”16

In the midst of so much culture, her Herald letters allowed her to begin to develop the critical opinions that she would hone during her literary career. Her hearing was still strong enough to allow her to make distinctions between the fine performance of the city’s premier amateur musical society and the disappointing Italian opera at the French Theatre, where the prima donna’s voice was past its prime. Ever a lover of the theater, she relished Joseph Jefferson’s performance of Rip Van Winkle and Edwin Booth’s of Cardinal Richelieu. She also told her Cleveland readers about the growing fame of their own Clara Morris, who had just made her New York acting debut in a new comedy.17

Constance felt sure of herself reviewing music and theater, but art was another matter. Having previously had little exposure to it, she was rather baffled by many of the works in the Academy of Design’s new exhibition. For now her taste in literature dictated her expectations from art: she was not so much on the lookout for beauty as for fidelity to reality. She apparently found little of it on display at the exhibition. The most flawed picture to her mind was “The Landing of the Pilgrims,” by an artist named Wopper, who, she determined, “certainly omitted the ‘A’ in [front of] his name.” Portraits of the Pilgrims in print or on canvas had been notoriously false, she admitted, but this picture strained all credulity: “One woman . . . is much to be pitied owing to the evident dislocation of her neck and the absence of any spinal column.”18

As James would later write of Henrietta Stackpole, “the great advantage of being a literary woman was that you could go everywhere and do everything.” Constance discovered this for the first time in New York, and forever after in her travels she carried with her the license of being a writer, which gave her the freedom to peer into the places mere tourists avoided. But she also wanted her pen to give her a kind of cover, hiding her from the stares of strangers, allowing her to observe without being observed. This is what prevented her from ever becoming a Kate Field or a Henrietta Stackpole. In later years, after her fame made the Herald attach her name to some letters she penned about her travels, she would feel the sting of exposure. She would come to loathe writing newspaper letters. “I do not like to approach so near the public. It is too ‘personal’ a place for a lady,” she decided.19

Fiction was a much safer place for a shy woman such as herself, for there she could express her opinions and feelings behind the veil of fictional characters. While in New York, she wrote two stories set at Christmastime that pay tribute to Dickens, who had died earlier that year, and provide glimpses of another New York. One, “A Merry Christmas,” featured Zeph’s war experience. The other suggests that however much the status of a literary woman freed her from convention, her gender, particularly as an unmarried woman, limited her access to the public world. In “Cicely’s Christmas,” New York becomes a cruel, inhospitable place for an unchaperoned female of limited means. It is Christmas Day, and a fashionable church is so overcrowded that Cicely can’t hear the music or see the service. She is forced to spend an exorbitant sum for a ten-course dinner, only half of which she is able to eat. The men of the city are rude and lascivious, jostling her on a crowded streetcar and ignoring her pleas for directions. At a play, admirers offend her with their advances. When Cicely complains, the usher replies unpityingly, “[M]ost ladies has gentlemen with them in such a crowd.”20

Although we can’t assume these were exactly Constance’s experiences, the story teems with the loneliness she felt in the bustling city. Despite the presence of Charlie and Flora and a visit from George and Clara, she felt like a “desolate spinster.” And although she had met many friendly people in New York, none could make up for the loss of Arabella and her father.21 After the initial giddiness over her freedom in New York, her sorrow about being all alone in the world had returned with a vengeance.

GONE!

On the morning of February 7, 1871, Constance awoke to a frantic knocking on her door and an urgent voice announcing that a telegram had arrived. The message within informed her that her brother-in-law, George S. Benedict, was presumed dead. She had seen him during one of his business trips to New York and had just kissed him goodbye, on his way back to Clara and the baby. His train to Cleveland had crashed outside of New Hamburg, New York.

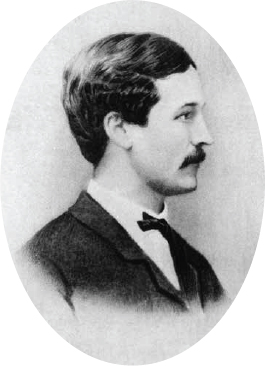

George S. Benedict, Woolson’s brother-in-law and adviser.

(From The Benedicts Abroad, vol. 3 of Five Generations (1785–1923))

Constance packed up her few belongings and caught the first train she could, taking roughly the same route as George’s doomed train. She was overcome with grief and terrorized by images of his fiery death. Harper’s Weekly called the accident “one of the most shocking disasters on record.” The train had collided on a bridge at high speed with a car carrying 500 gallons of oil, which had jumped a neighboring track. The subsequent explosion had burned the forward sleeping car, where George had been. He and his fellow passengers must have died instantly. For the rest of her life, Constance would refuse to sleep on trains, insisting on stopping for the night, even when only the humblest accommodations were available. Nearly twenty years later she would write, “I cannot see the curtains of a sleeping car without a sick feeling.”22

Back in Cleveland, Constance joined her shocked family and community in mourning. She spoke for herself and many others in her poem “In Memoriam. G.S.B. February 6, 1871”:

GONE! But we could not understand,

When broken voices said

That he was gone—we could not feel

That GEORGE, our GEORGE, was dead

Until they brought him home, his hands crossed on his breast . . .

So young, so beautiful, so strong,

So dearly, deeply prized,

So needed, trusted, leaned upon,

So loved, so idolized . . .

How can we spare thee, GEORGE? How live

Through the long dreary hours

Without thee? . . .

A small service for the family and close friends was held at Clara and George’s home. Pallbearers carried the casket to Grace Church, overflowing with mourners, where Arabella’s husband, Rev. Washburn, performed the service.23

George had become, in her father’s absence, Constance’s chief adviser and the male relative she relied upon. He was not only her chaperone on her first trip to New York but also her guide to the literary world. He had literally and metaphorically opened to her the doors that remained closed to so many women writers. Who would advise her now? Who would help her negotiate contracts or nudge unresponsive editors who owed her a check? If she were to continue her upward climb, she would have to learn to rise on her own or find another helping hand.

Constance wasn’t sure how to look forward. She later reflected, “I was so despondent, and the future looked so dark, yet I wouldn’t betray how I felt.” That summer came the news of Zeph’s marriage as well. In the stories she began to write of young women who found themselves forsaken and alone in the world, suicidal thoughts emerged. In “Hepzibah’s Story,” the heroine loses all interest in life but can find “no means of dying at hand.” Flower, in “The Flower of the Snow,” leaves Mackinac Island, murmuring, “Desolation! a land of desolation and death!” As she wanders through a bitter snowstorm that has complicated her departure, a devilish voice whispers temptingly in her ear, “What have you to live for? . . . Life will be long and lonely.”24 Constance may have shared her characters’ hopelessness, but she had to put on a brave face. Just as she had stepped into her father’s shoes, Constance now had to take George’s place in Clara’s home with the baby Clare (“Plum,” they called her) and their dependent mother. The part of herself awakened in New York—the literary woman who roamed and observed—was packed away, for good she feared.

Fortunately, Constance found that she was not as entirely alone in her literary pursuits as she had assumed. George’s father, who frequently stopped by Clara’s on his way home from work, became her new “mainstay.” He helped to sustain her connection to the world of ideas and writing, carrying on long conversations with her about his running of the Herald and the latest news. “[H]is encouragement and interest were everything to me,” she later explained. “I don’t believe I should have gone on if I had not had [him] behind me just at that time.” She wrote almost nothing that first year after George’s death, publishing a story in Appletons’, the essay on Cooper, and the two New York stories, which may have been written earlier. But the worries that always followed a male provider’s death brought back the question of how the women left behind would support themselves. Clara had only a small “guardian’s allowance” to support Plum. Charlie (according to the city directory) had returned to Cleveland and, boarding elsewhere, was working as a clerk; his salary would barely maintain himself.25 If the uncertainty of Connie’s economic future after her father’s death had launched her literary career, the greater uncertainty in the wake of her brother-in-law’s death would make her redouble her efforts and question what kind of writer she would be. Would she pursue profit or literary laurels? Was it possible to achieve both?

During the following year, Constance worked hard, publishing twenty new works, but her earnings were still no better than what a teacher could make, about $700. Even with the income from their father’s Wisconsin lands, they could barely get by. Then she read a newspaper announcement: the Boston publisher D. Lothrop was offering a $1,000 prize for the best new story for their “Sunday school series” of pious books for children. Constance was willing to try anything. The deadline was near, so she “shut herself up in her room and wrote as rapidly as possible.” Clara, out of desperation over their economic situation, did the same. Within a week, they both had manuscripts to enter into the competition.26

The early 1870s were a boom time for children’s literature, beginning with the colossal success of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women in 1868–1869. As Constance was beginning her career in New York, her old professor Samuel St. John from the Cleveland Female Seminary had visited her and given her “fully an hour’s eulogy of Miss Alcott’s ‘Little Women.’ ” She liked the book too “but could not place [it] above all else in the world.” The new cultural status of children’s literature annoyed her, but Alcott and her many imitators had opened up a rich new field, and St. John and others clearly thought this was where women writers could most profitably toil.27

The phenomenal success of an old acquaintance from her school days, who published What Katy Did in 1872, must have further convinced her to try her hand in the children’s market. Susan Coolidge was the pen name of Sarah Woolsey, who was an older sister of a friend from Constance’s schooldays. Constance must have noticed how the book reproduced sites and scenes from their childhood. In an early chapter a quiet war is waged between the girls at two neighboring schools—Mrs. Knight’s (or Mrs. Day’s, which the Woolsey girls attended) and Miss Miller’s (or Miss Fuller’s, which the Woolson girls attended). Constance was astonished at Sarah Woolsey’s success and “a little jealous.” Surely she could do as well, she thought, having herself told stories to her nieces and nephews for so many years.28

Hoping to mimic the successes of Alcott and Coolidge, Woolson wrote a book that similarly focuses on a group of children’s exploits—inspired by those of the Woolson, Mather, and Carter children—before they learn the important lessons they will need to become adults.29 Even the Woolson family dogs, Pete Trone, Esq., and Turk, made appearances. She also included a character much in the vein of Jo from Little Women and Katy from What Katy Did—a wild girl named Bessie who secretly races horses and longs for fame, in her case as an artist.

The Old Stone House won Woolson the coveted prize but not, unfortunately, all of the money promised. The publisher split the award between her and another author. Published in 1873 under the pseudonym Anne March (a tribute to Alcott), the book did not fail, but neither did it prosper. One reviewer, for The Youth’s Companion, found it “pleasant reading” and noted that it “reminds us of Miss Alcott’s ‘Little Women.’ ” The New York Mail proclaimed it “a vivacious, wholesome story, whose chief characters are neither prigs nor rowdies, but true girls and boys, romping and laughing and playing tricks, yet having manly and womanly hearts, that may well serve as examples.”30

Constance, however, was not happy with the results. She would never acknowledge the book, and her authorship of it remained a secret outside of Cleveland until after her death. She had written it too quickly and had to please not only her youthful readers but also a committee of clergyman. She later wrote, “When I had finished and read over the manuscript I was horrified to find it hadn’t the orthodox Sunday school tone but was simply a young people’s story. I went over it carefully and seasoned it at intervals with the lacking pious condiments.” About the same time she wrote a serial for a children’s magazine published in Cleveland, which must have been an equally unsatisfying experience, for she quickly gave up writing for children altogether.31

Clara, meanwhile, was undeterred by not winning the prize. She sent her manuscript out to other firms and found one willing to publish it, but without payment. One Year at Our Boarding-School was barely noticed by reviewers. One complained, rightly, that it read like a diary, concluding, “There is no predominant interest—no grand culmination.”32 If Clara had bested her in marriage, Constance outdid her in the literary sphere. Clara never attempted to publish again. From Constance’s letters, it appears that her sister was not particularly supportive of her writing, perhaps out of jealousy. Although the sisters would always be close, Clara would resent Constance’s growing devotion to her career.

Fortunately, Clara would soon learn that she and Clare could get by on their own small allowance, with the Benedicts’ assistance. Constance was determined to provide for herself and her mother by producing literature she was proud of. She would return to her earlier conviction that although children’s literature was worthy of a certain rank, “Shakespeare still existed, and Milton; the great historians, the great essayists, the great writers of fiction.” Remarkably, she set her sights on this latter category, to which few women writers—none of them American—had been granted access.33 Her early successes with the high literary magazines Harper’s and Appletons’ had stirred up her long-dormant ambitions. Thus this quiet, thirty-two-year-old woman from Cleveland, who had ventured into the literary arena seeking a means of support, began to hope and work for that most elusive of goals: recognition as a serious artist.