ONE DAY in the summer of 1882, Constance came upon a beaver in the Dresden Zoological Gardens who had pulled together a few branches in a futile attempt to make a dam. She stopped and stared at him for a while. He reminded her very much of herself—an American exile yearning for home and rather pathetically attempting to re-create it. “I suppose there never was a woman so ill-fitted to do without a home as I am,” she wrote to Henry James. “I am constantly trying to make temporary homes out of the impossible rooms at hotels & pensions.”1 Her wandering life had become its own kind of cage.

As the Benedicts planned their return to the United States, there was some talk of Constance returning as well. Instead, she accompanied them only as far as London. With their departure began a new period in her life. After so much time alone in Rome, Engelberg, and Sorrento, she entered more fully into expatriate society. “Everybody I knew, or have ever heard of, seems to be [in London] now!” she declared to Sam.2 John and Clara Hay, William Dean Howells and his wife, as well as various friends from Cleveland were all in town.

When everyone left for the winter, Constance followed the Hays to Paris, where James had just arrived from the countryside. Constance found “a quiet little place” where she could take meals in her own parlor. It was her first real glimpse of Paris, and although the weather was dreary, she enjoyed herself immensely.3 Whatever time she spent with James appears to have been brief. However, the trip was memorable for another reason. It was her first encounter with Hay’s close friend, the American geologist Clarence King.

By all accounts, everyone—from miners to royalty—fell under King’s spell. He was often described in superlatives. James called him “the most delightful man in the world,” and Hay dubbed him an “exquisite wit, . . . one of the greatest savants of his time.”4 King’s book Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada, published in 1872, combined the soul of a poet with the bravado of a mountain climber and made him a national icon. He was the first director of the U.S. Geological Survey and the foremost explorer of the mountainous West. (He named Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the continental United States.) King was strikingly handsome as well, with a brown beard, close-cut hair, and sharp hazel eyes. He was not tall—only five feet six—but had a commanding presence.

Woolson shared many mutual friends with King, among them Hay, Howells, Stedman, and James. Hay hoped to find the inveterate bachelor a wife and appears to have set his hopes on Woolson. They certainly had a lot in common: a fondness for grand mountains and wild places, a love of rowing, a peripatetic lifestyle, a preference for realism in literature and art, and, sadly, struggles with depression. Constance, however, wasn’t King’s type. He was notorious for pursuing women untainted by education or the trappings of Western civilization, such as the barmaids of London or the native women of Hawaii. He once wrote, “Woman, I am ashamed to say, I like best in the primitive state. Paradise, for me, is still a garden and a primaeval woman.” He would soon secretly marry an African-American woman and have a family with her, a fact his friends did not learn about until after his death.5

Constance met King in Paris one December evening and would many years later remember him as “one of the most agreeable men I have ever known.” He was “exquisitely kind,” she recalled. “He took me to the Comedie Francaise, with the Hays, & his sister, & I was much touched by his thoughtfulness.” Constance loved the theater, but it made her uncomfortable. She could find herself stranded on an island of silence as the audience erupted in laughter. King, with his characteristic attentiveness, sat next to her and repeated the actors’ words. After that night, Hay wrote to his friend Henry Adams that Woolson, “that very clever person, to whom men are a vain show—loved [King] at sight and talks of nothing else.”6 She had joined the band of the smitten.

King had promised to take Woolson to the Louvre, but she lost sight of him. Her feelings were “divided between liking and disappointment.”7 King no doubt reminded Woolson of Zeph Spalding and the adventuring male characters in her stories of the 1870s. He was a bracing wind all the way from the mythical American West. She would soon find herself caught up in a much stronger current, however.

THE WHIRL OF SOCIETY

After Paris, Constance returned to Florence and her old pension, the Casa Molini. Settling again into her writing routine and taking most of her meals in her room, she felt “at home.” She declined most invitations. She didn’t feel “strong enough to take much part in Society, or go out much, and do writing-work at the same time,” so she saved the “best” of herself for her writing.8

Her peaceful seclusion did not last, however, due to the arrival of William Dean Howells and his family. Whatever reservations she had about Howells were put aside as she came to know him well for the first time. As one of America’s foremost novelists, Howells received many invitations and was pursued mercilessly by the city’s “lion-hunters.” Soon the invitations started arriving for Woolson as well. She later explained to James, with her tendency to trivialize, “The same fate that befell the great masculine Lion, befell the very little feminine one—though on a much smaller scale.”9

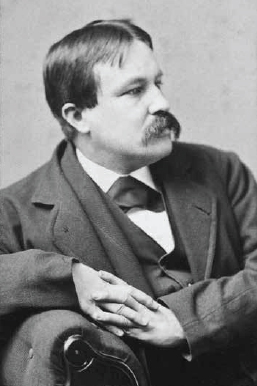

William Dean Howells, novelist and editor of the Atlantic Monthly. Woolson became close to him and his family during their visit to Italy in 1882–83. Photograph circa 1880.

(Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University)

Before long, Woolson’s days were full of visits and parties. She had so many friends in town and made so many new acquaintances that she set her own day to accept calls. Besides Howells and his wife and daughter, with whom she became very friendly, there were also the Hays, King’s sister, and her old friends from Rome, Lieutenant Commander Caspar Goodrich and his wife, who asked Constance to be godmother to their new son, Wolseley. He was a nice boy, she told Sam, but she regretted “wandering about the world, standing godmother to strange children” when Sam had a new baby in Cleveland.10

Florentine society was also full of expatriate artists and writers whom Woolson befriended. There was Violet Paget (pen name Vernon Lee), whom James thought “a most astounding female” with “a prodigious cerebration,” and her friend, the poet Agnes Mary Robinson. She also befriended Mrs. Launt Thompson, a writer and the wife of an American sculptor, and Eleanor Poynter, an English novelist and sister of the painter Sir Edward Poynter. Woolson was particularly fond of Miss Poynter, finding her “very quiet” and “appreciative.” Most of society overwhelmed her, however, generally reminding her of a “picture of wraiths & shades being swept round in a great, misty, crowded circle, by some bewildering & never-ceasing wind.”11

Constance was more at home with a group of men and women she met three times a week for six-to-eight-mile hikes in the hills surrounding Florence. On one of those hills, Bellosguardo, Constance met Miss Louisa Greenough (a sister of the sculptor Horatio), who lived next to friends of Henry James in the Villa Castellani, the model for Osmond’s home in The Portrait of a Lady. Astonishingly, Louisa Greenough, born around 1809, had known James Fenimore Cooper during his brief residence in a neighboring villa in the 1820s and was delighted to meet his relation. Frequent invitations addressed to Miss Fenimore Woolson made their way down the hill.12

However much Constance complained about Florentine “society,” it was not entirely disagreeable to her. She found that her age and occupation as a writer made her much respected, a rather novel experience for her. Women seemingly past their prime were not “shelved” as they were at home but were “important, considered.” Society, however, threatened to consume all of her time. She simply could not “be going out to lunches, & dinners, and evening-companies” and continue her writing.13 The “best” of herself was being siphoned off gradually but surely.

In the spring, Constance fled to Venice, where she was sure to have “no ‘calls.’ ” Although Howells and his family were also there and the dinner parties continued, she considered the smaller Venetian society much more manageable than that in Florence. Ever since a brief visit to Venice in 1881, she had longed to return. She had discovered then that “the perfection of earthly motion is a gondola” and decided that the “Floating City” was her ideal place.14

Woolson found rooms in the Palazzo Gritti-Swift, just above the English art historian John Addington Symonds, where she could see from her arched windows the busy Grand Canal, the Church of Santa Maria della Salute, the pink-hued campanile of San Giorgio, and the boats docked at the Riva Degli Schiavone. In the late afternoons she floated on the canals or enjoyed losing her way in the winding streets. She was starting to wonder, she wrote to James, “whether the end of the riddle of my existence may not be, after all, to live here, & die here.”15

Shortly after she arrived in Venice, she received a letter from James, who had gone to America after the death of his father. “[Y]ou have added much to the pleasure of my summer by writing as you have,” she replied. He had envisioned between them more talks “against an Italian church-wall,” but she asked him to leave out such images in the future, complaining that “there has never been but that one short time (three years ago—in Florence) when you seem disposed for that sort of thing. How many times have I seen you, in the long months that make up three long years?” He had as yet no plans for a return to Europe. He asked her to give him “ ‘a picture’—to keep [him] ‘going.’ ”16

She happily obliged, setting in front of him sumptuous visions of Venice and then inviting him mentally into her apartment, where she would make him a cup of weak tea, as he liked it, and invite him to sit on the plush sofa from which he could see out beyond the Grand Canal to the lagoon. She offered him her “infinite” “charity,” as he had called it. She preferred to name it “gratitude,” not for him personally, but for his writings, which “voice for me—as nothing else ever has—my own feelings; those that are so deep—so a part of me, that I can not express them, & do not try to.” She was reminded of how Hay had said in Florence that wherever his friend King was, “there is my true country, my real home.” She had said the same thing once to Stedman about Rome. If she could not have a literal home, she found it instead in James’s books, in which she felt her innermost self uncannily reflected. A few lines later, she implicitly contrasted herself to the wives of their friends Hay and Howells. Mrs. Hay, James had complained, “expressed herself with a singular lack of cultivation.” Now Constance commented on how Mrs. Howells was consumed by “[s]mall feminine malice, & everlasting little jealousies.”17 Constance was a very different sort of woman, she subtly conveyed to him, one who could appreciate his work and enter into his plans for future writing with full comprehension.

This letter also suggests a growing appreciation for James the man. She admired his decision to remain in America after his father’s death for the sake of his sister, who was “now, save for you, left alone.” Such a gesture meant a lot to her, also single and alone in the world. “That you are doing this only confirmed my idea of you—that you are, really, the kindest hearted man I know,—though this is not, perhaps, the outside opinion about you.” He was starting to look less like the self-centered author she had first glimpsed. The two letters Woolson wrote to James during her stay in Venice clearly show her venturing into a deeper intimacy, one that the tone of his letter from America had called forth. Although the common perception of James is that he was reserved and aloof, in reality he could be very warm and affectionate. Clearly he had swept away the embarrassment Woolson felt over telling him of her success with Anne. Her last letter to him from Venice concludes, “The lagoons, the Piazzetta, & the little still canals all send their love to you. They wish you were here. And so do I.”18

As the summer approached and the visitors began to pack their bags, Constance wrote in Winnie Howells’s autograph book “[Venice] is my ‘Xanadu.’—But not for always; Xanadu never lasts, you know!”19 She stayed on until the seventh of July, leaving finally after a slight illness made her seek out cooler climes and fresher air. Her final weeks in Venice were also tainted by the recent death of her godson, Wolseley Goodrich, whose parents had been staying there as well. Her story “In Venice,” published the year before, had presciently portrayed a child’s death in the water city. As magically beautiful as Venice was, for Woolson it was already associated with death.

SUFFERING SO PITEOUS

After leaving Venice, Constance made her way first to Engelberg and then back to Baden-Baden, where she met her old friend Jane Carter and her children, Mary, Grace, and Averell. Constance was delighted to renew their old closeness. Mary was now twenty-one, Grace nineteen, and Averell, another godson to Constance, fourteen. Jane had brought her children to Europe in the hopes of breaking off Mary’s engagement to a man who reminded Jane of her own ill-fated marriage to Lawson Carter, which had ended with his suicide in 1869. Constance became quite attached to the emotionally fragile Mary, perhaps recognizing some of her own moodiness and sensitivity in her. After the family left Baden-Baden, Constance wrote to Mary of the final gaieties of “the season,” recalling all they had done together: the musical evenings, races, walks up the hills to the ruins of Hohenbaden Castle, and royalty-watching.20

Constance was virtually alone in Baden-Baden when news arrived of a family tragedy. Her brother Charlie had died on August 20, 1883, in Los Angeles. According to county records, the cause of death was “suicide by poison.”21 Constance collapsed from the shock.

Charlie had seemed to be doing better. Afraid of another breakdown from working too hard in a cramped office, he had bought some farmland the year before with the help of the Mathers and possibly Connie and Clara. At the beginning of 1883, Constance reported that Charlie had been writing to her regularly. He was disheartened by the dreary winter, and she was concerned about how well the farm would do in the next season.22 But there was no cause for alarm. When summer came, he sank further, despite the California sunshine and promise of the coming harvest.

This time Charlie did not reach out to Constance. Instead, he kept “a sort of diary” over the summer. It appears that as he prepared to take his life, he mailed it to her. Charlie’s diary, she told Sam, “showed suffering so piteous that it broke my heart. I cannot imagine any suffering greater than his was, at the last.”23 After reading the diary, she destroyed it, as he had wished. But his agony imprinted itself on her mind. It would find its way at times into her writing, mingling with her own silent suffering.

The revelation of Charlie’s torment and suicide plunged Constance into her first deep depression since her mother’s death. She told Sam she had never suffered so much in her life. Charlie’s death so far away had made her “perfectly desolate, &, for a time, it seemed to me that I cd. not rally from the depression it caused; & that it was hardly worth while to try.” Physically, she was also suffering from a series of painful ailments. She could hear her father’s voice telling her to “[k]eep a stiff upper lip.” Over time it began to drown out Charlie’s final cries. But it would take months for her to regain courage enough to face even the simplest of tasks.24

The only known photograph of Charlie Woolson. His death shortly before his thirty-seventh birthday was devastating to Constance.

(The Western Reserve Historical Society)

After being paralyzed for weeks, unsure where to go next, she decided on London, arriving in October and planning to stay through the winter. She had long been drawn to its culture, history, literature, and landscape and had hoped she could spend part of every year there while she was abroad. But everyone seems to have discouraged her, worried that the dark, foggy days and cold, damp weather would be detrimental to her health and emotional state. Only Jane Carter was supportive, advising her to give it a try.25

To her delight, London was warmer than Menton had been and the houses more properly heated. She enjoyed the homey comforts of England. And the darkness didn’t bother her; it was cold she feared. She was lucky. According to James, it was the “most beautiful winter I have known in England—fogless and frostless.” In the middle of January, the temperature rose into the fifties.26

James had returned to London on the first of September, and his presence was probably another reason Woolson chose London. She had glimpsed a tenderness in his last letters and probably wondered if he could be a harbor in her emotional storm. There was no other friend in Europe just then she could turn to. She would not only give London a try, but James as well.

Seeing the crisis she was in, he did not turn away. In fact, during the eight months she lived in London, the two friends saw each other often and began what would be one of the closest relationships for either of them outside of their families. So close was it that they would one day decide to destroy their letters to each other, hers from Venice being the last to have survived. We can only piece their friendship together now from fragmented, often veiled references in their letters to others.

James told his good friend Lizzie Boott that if she came to London he could “make a place” for her, “in spite of the fact that Costanza has just arrived,” suggesting Constance occupied the principal place just then. Later that winter James wrote to Howells of Woolson, whom he claimed to see “at discreet intervals”: “She is a very intelligent woman, and understands when she is spoken to; a peculiarity I prize, as I find it more and more rare.” Only a few weeks earlier, Woolson had indicated to Sam that James visited her “now & then,” while her neighbor noted to John Hay that James came “frequently” to call on her.27

Her neighbors were French Ensor Chadwick, naval attaché for the American Legation in London, and his wife, whom Constance had met in Florence (they were friends of the Hays and Goodriches). They had found her an apartment below theirs in Sloane Street, South Kensington, and were “kindness itself,” Constance informed Sam. “They have done everything they cd. think of to add to my comfort & keep me from too much loneliness.”28

Unfortunately, though, it seems the Chadwicks were not able to help her recover from her depression. As she explained to Hay, whose health had also not been good, Chadwick was “one of the best fellows in the world,” but he couldn’t understand the kind of grief and illness she and Hay endured. “I really think that he believes I cd. have got better sooner, if I had only tried!” she complained. Hay understood, however, “the illness that hangs on, & baffles effort, & takes the heart out of a man.” Just as she had with Paul Hamilton Hayne many years before, she now found a companion in her depression, but Hay was far away. James was nearer and had a good deal of experience with depression, having witnessed his brother William’s battle with it in 1869–1870. He was no stranger to depressive episodes and was experiencing his own “pronounced state of melancholy” that winter after the deaths of his father and good friend Ivan Turgenev, the Russian writer.29 His younger brother Wilky, who, like Charlie, had failed to fulfill his early promise, was also declining rapidly.

A letter James wrote a few months later to his friend Grace Norton indicates how much he understood the kind of psychic crisis Constance was experiencing. He told Grace, “You are not isolated, verily, in such states of feeling as this—that is, in the sense that you appear to make all the misery of mankind your own.” Like Constance, Grace was prone to absorb the suffering of others and question the value of a life so filled with pain. In response, James was determined to speak “with the voice of stoicism.” Even in the absence of religious faith, he believed, “we can go on living for the reason that (always of course up to a certain point) life is the most valuable thing we know anything about and it is therefore presumptively a great mistake to surrender it while there is any yet left in the cup.” He had faith ultimately in the “illimitable power” of human consciousness. He begged Grace to “remember that every life is a special problem which is not yours but another’s, and content yourself with the terrible algebra of your own. Don’t melt too much into the universe, but be as solid and dense and fixed as you can. . . . Sorrow comes in great waves . . . and we know that if it is strong we are stronger, inasmuch as it passes and we remain.”30

Far from the uncomprehending admonition simply to get well that Chadwick had offered Woolson, James’s advice acknowledged the depth of his friend’s pain. So must he have conveyed to Woolson a solidarity in suffering that would have been immensely comforting at a time when she felt alone in the world. It was precisely what she needed to separate herself from Charlie’s troubles and find purpose again in her work—that “illimitable power” of consciousness that was the province of the writer. Yet, in her writing as well as in her life, she found it hard to let the troubles of others wash over her.

By January Constance told Sam, “I have conquered, & got a firm hold of myself again.” She had fought her way back to “the interest I was full of last summer” and “the habit of daily work.” When Hay came over in May, he was pleased to report to his brother-in-law Sam that he and Constance had had many talks and that she was “busily engaged upon her new novel with all the energy of recovered health and spirits.” She relished the opportunity to discuss literature with Hay and welcomed him to the band of novelists. His anonymous novel The Bread-Winners, his first, had just finished its run in The Century. She had written to him in January, “I am terribly alone in my literary work. There seems to be no one for me to turn to. It is true that there are only two or three to whom I wd. turn!”31 James would soon become one.

Less than a month later, James indicated that he was reading her work, writing to Howells that he was “the only English novelist I read (except Miss Woolson).” James was used to telling his novelist friends what he thought of their work. Many of them trembled to hear his opinions—“I am afraid I have a certain reputation for being censorious and cynical,” he wrote to the writer Mrs. Humphry Ward.32 Woolson, however, had often asked for frank criticism and found few who would provide it. Constructive criticism encouraged her to aim ever higher, as the Appletons’ review of Two Women had done. It is probably no coincidence that she began to write the most ambitious novel of her career as James began to read her work.

During Hay’s visit in May, Woolson saw him often and finally had the chance to ask his advice on publishing matters. He urged her to request more money for the serial rights of her new novel, but she wasn’t sure she would dare to. King was also in London and had been for months. Woolson was disappointed he had not called on her. Finally he did. “One visit was all I required to revert comfortably to my old opinion of him,—which was superlative,” she told Hay. But one visit was all she would have. She felt as if he had “dropped” her, she complained to Hay, who “comforted [her] by the disclosure that he had dropped, in the same easy way, two Duchesses and the Prince of Wales.”33

During the spring, when she wasn’t writing she “prowl[ed] about this dear, dusky old town.” She found all of the sites associated with Thackeray and Dickens and enjoyed the galleries.34 In June, the Benedicts returned, this time with Kate Mather. Constance secured rooms on Portman Square near Hyde Park and found herself surrounded by young women—not only her two nieces, but also the Carter girls, Mary and Grace (with their mother, Jane), as well as Mary’s friend, Daisy, whose real name was Juliette Gordon Low (the future founder of the Girl Scouts).

In July, while the others went to Germany, Constance moved just outside of London to Hampstead, a lovely, hilly town where she could enjoy cooler weather and get some work done high above the London smoke and smog. James visited her often there and wrote to Lizzie Boott that Woolson was “a most excellent reasonable woman, . . . I like and esteem her exceedingly.” He was impressed to find her so “absorbed in her work.”35

Her stay in Hampstead was short, however. Her rooms were too small and damp, so she went back to London, where the summer heat soon overwhelmed her. James was in Dover just then, finding the quiet conducive to work. Constance decided to pack her bags and head for the white cliffs as well.36 This was the first of their many secret rendezvous. Neither mentioned the presence of the other in their letters. Unmarried as they both were, such meetings could invite scandal. Although James had come to Dover to work, he apparently didn’t mind having the hardworking Woolson there as well. They both understood that the other needed time to write and thus were settling into an easy companionship.

Near the end of September, as James resettled in London, Woolson moved to the town of Salisbury, where she spent two blissful, solitary months finishing her new novel. Her time there was one of her happiest abroad. She had always “dream[ed] of spending a few weeks in an English Cathedral town.” Her landlord, one of the pulpit vergers, secured her a seat in the thirteenth-century cathedral’s choir. She often stayed after services to let the great organ’s rumbling tones wash over her.37

Her mornings were spent hard at work in her rooms, which looked out over the garden and a beamed house “as old as Shakespeare’s time.” In the afternoons, she walked into the countryside in search of Norman or medieval churches. On her way home in the cool evenings, she enjoyed spying through glowing windows the cozy scenes of clergymen and their families busy with their tea.38 Then she happily returned to her rooms for her own tea and read or wrote letters by gaslight.

On September 29, James came down from London, the first time he made a special trip to see her. The pair hired a carriage to take them to Stonehenge. Buffeted by a cold wind, they wandered underneath the towering stones in silence. On the way back to Salisbury, their carriage pulled off into a ditch, where they cowered for half an hour while the wind roared overhead. Back in her lodgings the two dined and then went to a local theater for a rendition of Richard Sheridan’s society farce A School for Scandal.39

EAST ANGELS

In January 1885, Woolson’s new novel began to appear in Harper’s magazine, running concurrently with Howells’s Indian Summer. She resented the fact, fearing his work would overshadow hers. East Angels was her longest novel at six hundred pages. It was, in fact, the longest novel published in Harper’s thirty-five-year history. Her decision to write a long work was motivated in part by economic need. It was becoming clear that she would have to produce a long novel every two to three years to support herself sufficiently. Her royalties in 1883 had been over $2,000 (nearly $50,000 in today’s money). By 1885, they were only $200 (about $5,000 today). Taking Hay’s advice, she had asked for a raise for the serialization of East Angels, requesting $3,500 (today, $87,500). The Harpers accepted her terms.40

If Woolson had put all of her youthful self into Anne, she put all of her adult ambitions into East Angels. It is her most fully executed realist novel in its analysis of character and motivation. In East Angels, she tested her interest in the analytical novel. Some have noted this novel’s affinity to James’s works, despite its exotic Florida setting, and seen it as an answer to The Portrait of a Lady.41 Woolson had also drawn from one of his greatest influences, Ivan Turgenev, whose works she had grown to love. She learned from him, as James had, to let her plot grow organically from her characters. In writing East Angels, she wasn’t so much choosing sides in the literary debates then raging as she was experimenting with how far she could take the analytical mode. The result is a work that deserves to be read alongside James’s Portrait.

The plot is easily told: a group of northerners settles near St. Augustine, and two of them—Margaret Harold and Evert Winthrop—fall in love. However, Margaret is married to Evert’s cousin, who has abandoned her, and she will not divorce him. James heartily approved of the work, writing, “[W]hat is most substantial to me in the book is the writer’s . . . general attitude of watching life, waiting upon it, and trying to catch it in the fact. . . . [A]rtistically, she has had a fruitful instinct in seeing the novel as a picture of the actual, of the characteristic—a study of human types and passions, of the evolution of personal relations.” While James had brilliantly dissected his characters’ consciousness, Woolson was after their hearts as well, believing the drama of inner life incomplete without a close examination of characters’ emotional states. She was, in a way, applying the new analytical method to the timeless themes of literature, those of the Greeks, Shakespeare, and the Romantics. After a long period in which the genuine expression of emotion had been highly valued, however, the late nineteenth century was becoming increasingly suspicious of it, even demanding its suppression. As the novelist Frances Hodgson Burnett put it in in 1883, “There is a fashion in emotions as in everything else. . . . And sentiment is ‘out’ ” as is “grief.” On the other hand, “making light of things” was in.42 East Angels, like so much of Woolson’s fiction, charts this transition from a Romantic world of feelings to a modern world of restraint. The shift away from the direct examination of emotions would in fact become central to the invention of modern literature, which would, following particularly in James’s footsteps, concern itself with inner consciousness.

Woolson had reproved James for not showing readers whether his heroines truly loved. There had been no evidence in Isabel of the kind of “heart-breaking, insupportable, killing grief” that surely would have followed her discovery of Osmond’s perfidy, had she loved him. Almost as if Woolson were showing James how it could be done, she proceeded to portray, with the methods of a realist, the “killing grief” of a woman who loves deeply but silently. Much of the pathos of East Angels derives from the way its heroine, Margaret Harold, must constantly repress her emotions, as her era demands. What others perceive as Margaret’s coldness and self-righteousness is really a desperate attempt to maintain self-control. “We go through life,” she tells the younger Garda, “more than half of us—women, I mean—obliged always to conceal our real feelings.”43 While Garda refuses to guard her feelings, Margaret hides her face whenever she is near Evert Winthrop. She escapes his presence as quickly as she can. Like her creator, she seeks out solitude, particularly in nature, as the only safe place where she can drop her mask and allow her face to express the feelings within.

Whether or not Margaret is right to hide her feelings and then to refuse to act on them when Winthrop forces them out of her is not the point of the book (although this would be the point on which critics fixated). The point is simply for the reader to understand Margaret and to empathize with her. While to other characters she is so “good,” particularly when she chooses to stay with her negligent, philandering husband, Woolson shows us the great strain and almost superhuman effort that goes into her self-sacrifice, exposing the costs of women’s inability to reveal their true selves. Once, near the end, Margaret expresses bitterness about repressing her feelings. She challenges Winthrop, who is trying to lure her away: “You talk about freedom . . . what do you know of slavery? That is what I have been for years—a slave. Oh, to be somewhere! . . . anywhere where I can breathe and think as I please—as I really am! Do you want me to die without ever having been myself—my real self—for even one day?” Winthrop later asks her, “[D]o you wish to die without ever having lived?” He offers her love and life, but Margaret steadfastly refuses, viewing divorce as a great wrong (as Isabel Archer had). In the struggle between Winthrop and Margaret, he threatens to force her acquiescence by overpowering her, but she looks at him, her eyes “full of an indomitable refusal,” and tells him, “I shall never yield.”44 Maintaining her self-control is the only way she can maintain her self-worth.

Writing East Angels drained Woolson physically and emotionally. After the serial version was finished, she wrote to Hay, “[O]ne novel takes my entire strength, & robs me of almost life itself! I am months-recovering.” Her writing process was remarkably arduous. She first wrote a detailed version of the entire plot, then a thorough description of each character, and finally exhaustive accounts of each scene with numerous pages of conversation, much of which never made it into the final book. In fact, all of this prewriting was many times longer than the actual book. To transform it into a coherent novel, she had to piece together the various parts, condense scenes and dialogue, and make them fit into the prescribed space allotted in each issue of the magazine. All of this could take up to two years. As she later explained to her niece Kate, “I don’t suppose any of you realize the amount of time and thought I give to each page of my novels; every character, every word of speech, and of description is thought of, literally, for years before it is written out for the final time. I do it over and over; and read it aloud to myself; and lie awake and think of it all night. It takes such entire possession of me that when, at last, a book is done, I am pretty nearly done myself.”45

Throughout the lengthy, painstaking process, she also poured her emotional life into her work. “Nothing is true or effective which is not drawn from the heart or experience of the writer,” she wrote in a journal she titled “Mottoes, Maxims, & Reflections.” When asked to respond to a debate about whether or not writers must be moved to tears in order to similarly move their readers, Woolson responded affirmatively, citing “the account of the way George Eliot’s books ‘ploughed into her’ [and] the description of Tourguenieff . . . as pale, feverish, so changed that he looked like a dying man, because the personages of one of his tales had taken such possession of him that he was unable to sleep.”46

While she was writing East Angels, a pitiful tone entered into her letters, not unlike Winthrop’s words to Margaret during one of their final meetings: we “have nothing—[we] are parched and lonely and starved.” In the summer that she began working on the book, she claimed to be “mournful, and lonely.” In January, as she returned to work after her illness, she was again “lonely, & not much entertained with the spectacle of daily life.” Despite the visits of Clara, her two nieces, and the Carters, she felt increasingly as if her circle of family and friends was narrowing.47 She openly envied those with spouses and children and began portraying herself as starved for affection and human interest. It was as if Margaret’s fate and her own were entwined.

Writing East Angels had also made Woolson homesick for Florida. She declared to Hay, “[T]here is not a twig, or flower, described in ‘East Angels’ that is not literally ‘from life.’ ” She would move back tomorrow if she could get a small house in St. Augustine.48 When the widower of her old St. Augustine friend Mrs. Washington told her he was saving six acres twenty miles south of the city for her, she called it “East Angels” and began making vague plans to build a cottage and retire there in ten years or so.

The publication of George Eliot’s Life as Related in Her Letters and Journals, which Woolson read not long after she finished East Angels, revived her feelings of loneliness and resentment toward those who basked in an atmosphere of love and devotion. While in London she had learned all about Eliot and Lewes’s marriage in practice if not in fact (he was unable to divorce his wife) and her feelings about her old idol had changed. She did not begrudge Eliot the right to live with Lewes, but she was clearly jealous of the steadfast love they shared: “[S]he had one of the easiest, most indulged and ‘petted’ lives that I have ever known or heard of. . . . True, she earned the money for two, and she worked very hard. But how many, many women would be glad to do the same through all of their lives if their reward was such a devoted love as that!” What Woolson objected to was “that after getting and having to the full all she craved, then she began to pose as a teacher for others! She began to preach the virtues she had not for one moment practised in her own life.”49 Woolson could not be accused of any such hypocrisy. She practiced the virtue of self-renunciation as vigorously as Margaret Harold did. And she feared she would one day die, like Margaret, without having fully lived.

MEETING ALICE

After a dismally cold winter in Vienna with the Benedicts, Constance returned to England, moving this time to the Isle of Wight. She was relieved to be back in England, but a week after her arrival she was struck with a “troublesome affection of the nerve of the spine” that she blamed on writing too much. She could not use her hands at all. She became anxious and depressed and confessed to Mary Carter that she broke down and cried at times.50

Woolson had this photograph taken while she was staying in Leamington and unable to write.

(The Western Reserve Historical Society)

The saline baths of Leamington, where she soon moved with Clara and Clare, relieved her pain, but she still could not write much. The three made excursions in the vicinity to places like Stratford-upon-Avon and Oxford, with which she immediately fell in love. After her sister and niece sailed home in September, Constance occupied herself by strolling through the lush gardens of nearby Warwick Castle and reading English memoirs and biographies. England felt like home, yet she was thoroughly worn out and irritable. Finally she consulted Dr. Eardley Wilmot, whose treatment, which probably utilized the Leamington spa waters, enabled her to start writing again.51 She was desperate to get back to work; the Harpers were awaiting the book revisions of East Angels.

Although Woolson had earlier planned to spend the winter in Venice or Florence, she headed to London, returning to her old lodgings in Portman Square. James may have suggested the move. He was a mile away in Piccadilly. He gave her a copy of The Bostonians that winter and introduced her to his sister, Alice, and her companion, Katharine Loring, who lived five minutes from him.52 For years Alice had struggled to maintain her mental and physical health. She had stayed at asylums, received electrotherapy treatments, sought out renowned doctors in New York, and traveled to Europe in hopes of improving her condition. With both parents now dead and Henry and Katharine devoted to her care, she made a new home for herself, primarily in London and later in Leamington.

The apparent cause of Alice’s suffering was the struggle between her fierce will and the great effort to suppress her intense feelings, the precise conflict Woolson had described in her character Margaret Harold, who also fell ill when her emotions got the better of her. Alice thought of herself as “an emotional volcano within, with the outward reverberation of a mouse and the physical significance of a chip of lead pencil.” Her oldest brother, William, called her “bottled lightning.”53 Alice and Constance were in some ways twins under the skin. The great difference between them was that Constance had found a vocation and an outlet for her emotions, while Alice was effectively silenced by her overbearing father and highly accomplished two older brothers. In 1889, three years after meeting Constance, Alice would begin to find her voice by writing the diary that would be her life’s great work.

Alice James, Henry James’s sister, whom Woolson came to know in London, during the winter of 1885–86.

(Correspondence and Journals of Henry James Jr. and Other Family Papers, MS Am 1094 [2247, f.44.4], by permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University)

In the winter of 1885–1886 Constance quickly became “[o]ne of Alice’s preferred new friends.” However, they were also rivals for Henry’s attention. Alice’s jealousy toward her brothers’ female friends could be severe. When William announced his engagement in 1878, Alice took to her bed for months, “on the verge of insanity and suicide,” as her father put it. In the case of Henry’s relationship with Constance, Alice complained to family members of his “flirting” and “galavanting [sic]” with her. In the years ahead, Constance would be careful to downplay the closeness of her relationship with Henry. In one letter, the only one she wrote to Alice that has survived (and only in fragments), she makes sure to point out that the letter she has just received from Henry, who was ill in Venice, was only “a few scribbled lines,” lest Alice feel aggrieved at not having heard from him herself.54 Nonetheless, frequent notes were exchanged between the two friends in the coming years, and Woolson would also develop a warm relationship with Katharine Loring.

That winter, the day after Christmas, Woolson received a note from Henry James informing her of the death of Clover Adams, wife of Henry Adams and close friend of the Hays. She had been a witty, intelligent woman—a “perfect Voltaire in petticoats,” in James’s words—who had found few opportunities for intellectual stimulation. Upon hearing the news, Woolson immediately wrote to the Hays, describing Clover’s death as “sudden.” Although the exact cause of her death was a well-guarded secret, James learned of it afterward and surely passed the news on to Constance. Clover had swallowed photo-processing chemicals, unable to recover from the death of her father and, as James said, “succumb[ing] to hereditary melancholy.”55 It must have reminded Woolson of her brother’s suicide. It was also another instance of the “killing griefs” that could rob one of the will to live.

The winter was inauspicious in other ways as well. London was experiencing rampant unemployment that led to riots. One day in February, Woolson was caught up in a mob making its way down Piccadilly. She escaped unharmed, but the unrest lasted for days. In the dark, cold days of winter, “ ‘Babylon’ seemed doomed.”56

Nonetheless she lingered into the spring to finish the book revisions of East Angels, allowing herself to spread out beyond the confinements of its serialized form and perfecting its language. The magazine version of her novels never satisfied her. Only as a book could the novel be realized as she had imagined it. When she finally finished, at the beginning of April, with her eyes, hand, and back completely worn out, she departed for Florence, the city of rebirth.