THE LOMA PRIETA EARTHQUAKE struck Northern California at 5:04 p.m. on October 17, 1989. The earth shook for only twenty seconds, but in that brief time, its immense power was felt as far away as San Diego and western Nevada. Buildings collapsed in the Marina district of San Francisco, some sinking several stories into the liquefied ground. One section of the Bay Bridge, which links San Francisco with Oakland, fell. Many deaths occurred when the Cypress Street section of Interstate 880 collapsed like a pancake, killing those on the lower level.

At the time of the earthquake, I was at work in Palo Alto. I remember huddling in the vestibule of the men’s room, wondering if this was the big one. I remember watching as a jagged crack formed, as if in slow motion, in the wall in front of me. As soon as it seemed safe, I rushed outside to the open-air parking lot. Others had already turned on their car radios to determine the extent of the damage.

In the first hours following the earthquake and into the next day, there was a palpable giddiness. We were alive; everything was okay. But then a collective stupor seemed to descend. In San Francisco, it became oddly still as people walked and drove around in shock, unable quite to grasp the reality of the event. We needed time to come to terms not just with what had happened, but with what it meant: that we lived our lives on shaky foundations.

Some people found this reality more than they could handle and moved away, presumably to safer ground. Most of us stayed. But in the weeks and months following the quake, we lived with strong memories of the event and with its emotional aftermath. Because PARC’s main building, where my office was located, had suffered significant damage, we weren’t allowed back in for several weeks. I discovered that whenever I was in a stairwell, the walls seemed to shake. This reaction, presumably a form of post-traumatic stress, lasted for weeks. But for several months more, whenever I drove under an overpass on the freeway, I was briefly gripped with fear that it might collapse. And if I happened to be stopped in traffic under an overpass, my anxiety increased with the passing seconds. In time, of course, these reactions subsided. The memories of the quake faded, as did the awareness of my vulnerability.

The existential significance of this whole experience was summed up by one odd little coincidence that happened in the first day following the quake. For several weeks I had been house-sitting for acquaintances in San Francisco, and had been commuting between San Francisco and Palo Alto, a distance of about thirty-five miles. Because the condition of the roads was uncertain immediately after the earthquake, I decided not to venture up to the city that night. The next day, as I headed back to the house, I was understandably concerned about what I might find. So I was relieved to discover that the house was still standing, and seemed not to have suffered any noticeable damage. As I conducted a tour, room by room, however, I discovered something — an accident? a meaningful co-occurrence? — that gave me pause for thought.

For a month or so prior to this, I had been taking a class in Biblical Hebrew at Stanford. Our assignment for the week had been to translate Psalm 104 from Hebrew to English. There on the kitchen table was my class notebook, exactly where I’d left it the morning before. It was open to the last line I had translated on the morning of the earthquake. My translation of line 5 read:

God has set the earth on a firm foundation so it won’t shake.

But there was more. This was a home filled with books. Bookshelves lined the walls, yet hardly a book had fallen throughout the house. But when I went downstairs to the study, where my computer was installed, one of the owner’s books had fallen onto the desk from a bookshelf above it: Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval.

This immediately struck me as funny. Upstairs, one source declared that the earth doesn’t shake; downstairs another proclaimed the opposite. Here was a divine riddle, or perhaps a Zen koan: How is it that the earth shakes and doesn’t shake? Whether by chance or design, this juxtaposition of messages seemed to pose a series of related questions: Where does our stability come from? Where can we find solid ground? In the end, what can we really rely on?

It is curious that the Book of Psalms played a role in posing these questions. Over several millennia, many millions of people have looked to this book — and the Bible more generally — as a source of answers to life’s great questions. Living through trying and uncertain times occasioned by earthquakes, wars, illness, divorce, and the nearly endless forms of human suffering, countless people have found comfort in the words of sacred scripture. Not just the words, though, but the physical volume — solid, substantial, lovingly tended, and perhaps handed down from generation to generation — has itself served as a symbol and a reminder of cosmic safety and security. And the fact that the book was mobile, that it could be carried from place to place, meant that it could serve as a traveling reminder — that it could, in effect, provide a sense of home away from home.

George Steiner makes this very point in an essay called “Our Homeland, the Text.” He suggests that for Jews living in exile over many centuries, the Bible, or Torah, as it is called in Hebrew, has been their homeland, “the literal-spiritual locus of self-recognition and of communal identification.”1 Jews have figuratively carried the Torah on their backs, and it has provided them with “an unhoused at-homeness in the text.”2 Of course, it isn’t only Jews but Christians for whom the Bible (admittedly a somewhat different collection of texts) has provided a sense of identity and stability. Nor is the Bible the only “book” that has anchored faith communities. Muslims, Buddhists, and Hindus (to name three prominent traditions) have all drawn strength and direction from a small set of canonical texts. In each case, a community’s sacred literature has helped its members address some of the most basic, existential questions of human life: Who am I? Where do I come from and where am I going? What is death — and, for that matter, what is life? What is to be valued, and in what can I place my trust? What is the nature of the universe, and how should I act in it?

Of course, it isn’t only sacred literature that has provided this kind of practical, moral, and at times spiritual orientation. Just look at the role the U.S. Constitution has played in establishing and maintaining American culture and identity. The Constitution is more than the founding document of the American nation and the basis for its legal system; it is the locus of many of the nation’s values, and, through a process of ongoing interpretation, the formal mechanism by which the society has set its moral and practical compass. In a related manner, the Western canon — the collection of culturally authoritative literary and philosophical works stretching from Plato to Shakespeare and beyond — has also served as a source of identity and stability akin to the Bible or the Constitution. Indeed, the “culture wars” of the last decade or two can be seen as a religious struggle over whose literature (and whose values and worldview) should predominate.

So it isn’t hard to see great documents like the Bible, the Constitution, or the works of Plato and Shakespeare as sources of stability, providing meaning, direction, and reassurance in the face of life’s uncertainties. But I would venture to say that this is true of all our documents, from cash register receipts to children’s notes, from greeting cards to Web pages — for all of them aim to provide some measure of stable ground in an unstable world. You probably wouldn’t want to say that a cash register receipt offers answers to the great questions of life the way the Bible aims to, or that it is the basis for practical guidance on the scale of the Constitution. Yet in a curious and profound way I do believe that documents — all of them — address the great existential questions of human life. I’m also convinced that we can’t see documents most fully for what they are without framing them in existential terms.

Before I can elaborate on these statements, though, I need to say something about the existential dimension of cultural order. On this subject, I have been strongly influenced by the work of the cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker and his writings on the relationship between death, anxiety, and culture. In his Pulitzer Prize—winning book The Denial of Death, Becker argues that death — our inability to come to terms with our mortality, our fear and denial of it — is the primary fuel for all of human culture. Death, he claims, quoting William James, is “the worm at the center of the apple,” the inescapable condition of human life, which eats away at our projects, our sense of ourselves, our hopes and dreams. How can there be lasting meaning and value in the face of our fragile and temporary existence?

Building on other existentialist thinkers, most notably the Danish philosopher Kierkegaard, Becker sees human anxiety as the result of our inability to come to terms with our finitude. Although it may manifest itself in particular issues in our lives — in concern for our health, for our family’s well-being, or for our own career advancement — this anxiety actually springs from a deeper source, the core of our being, and has less to do with specific conditions than with our relationship to life itself.

But death, in and of itself, can’t be the cause of our anxiety, Becker observes. Death is only a problem because we know that we will die. Most other creatures on the planet presumably live in blissful ignorance of their ultimate end. This makes human consciousness a mixed blessing at best, for it is at once the source of humankind’s unique achievements and also of its greatest terror. Following Kierkegaard, Becker reads the story of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden as a parable on the emergence of human consciousness. Adam, upon eating from the Tree of Knowledge, discovers his dual nature: that he is a mixture of earth and divine breath.

We therefore live with a nearly unbearable burden — not just the knowledge of our mortality, but the anxiety that accompanies this knowledge. Because we cannot live with the awareness of our smallness, our incompleteness, our mortality, we find ways to suppress or deny the reality of our plight. We try to build ourselves up, to make a “success” of ourselves; or we give ourselves over to something larger: a leader, a cause, an ideal.

Becker sees human culture as the playing field on which this drama is continually enacted. There are endless ways in which we attempt to make something of ourselves and thereby “outlive or outshine death and decay.”3 Some of us pursue wealth and power. Others attempt to create lasting works or monuments, or to excel in sports, or to raise children who will accomplish what their parents failed to do. But these attempts at heroism are only possible because human culture creates the conditions for them. (You can’t be rich without a communal notion of wealth, or powerful without social structures of hierarchy and dominance. What are works or monuments or sports or families, apart from the human lifeworld through which they are defined?) Apart from what it allows us as individuals to do, human culture — the whole continuous run of it from thousands of years ago into the indefinite future — is our collective immortality project.

A second, more recent work adds an interesting twist to Becker’s analysis of the human condition. In a book called Lack and Transcendence, David Loy, a philosopher, builds on the groundwork that Kierkegaard, Becker, and others have laid. He too sees in human life a retreat from chaos and an attempt to escape anxiety. But he disagrees with Becker that the root cause of our dilemma is the fear of death. Loy observes that for each of us death is in the future. While death may certainly be terrifying to contemplate and fearful to anticipate, there is something even more terrifying right now, and it is this that is the true source of our anxiety.

Loy calls this something lack. This is the sense that we are incomplete, that we are flawed, inadequate, not enough. Much as Becker suggests that we will do anything to avoid facing our mortality, Loy suggests we will do anything in the attempt to escape from or to nullify our sense of lack. Driven by lack, we are constantly searching for more: more material possessions, more status, more love. But, alas, we discover again and again that the latest attainments provide only temporary satisfaction. There is still more we lack, and we go chasing after it.

But such efforts to acquire enough, or to become enough, as a way of escaping our lack are doomed to failure. Drawing on Buddhist philosophy, Loy suggests that the sense of lack is a necessary concomitant of the self. Each one of us, by virtue of having a self, is continually struggling to discover “ourself” and to know that we are real. What drives us is the suspicion that “I” am not real. Descartes’s famous dictum, “I think therefore I am,” was one attempt to resolve this dilemma. (The very fact that I doubt I am real is proof that I am.) Buddhism, however, doesn’t accept this way out. “Rather than being autonomous in some Cartesian fashion,” Loy says, “our sense of self is mentally and socially conditioned, therefore ungrounded and . . . fragile.”4

We want to know that we are real, that we stand on firm existential ground, that we are whole. But this longing is doomed from the start, because our true nature can only be found in our relatedness; in our very being we are inseparable from one another, nature, the universe. It is an unfortunate property of the self — an inherent property — that it sees “itself” as independent, can’t find the grounds for proving this (because no such grounds exist), yet persists in searching obsessively for them. This hole at the center of the self leads us to acquire and to accumulate, to plan, to try to build ourselves up. “To the extent I come to feel autonomous, my consciousness is also infected with a gnawing sense of unreality, usually experienced as the vague feeling that ‘there is something wrong with me.’ Since we do not know how to cope with such an intimate sense of lack, it is repressed, only to return in projected form as the compulsive ways we attempt to make ourselves real in the world. . . “5 Even the fear of death, Loy suggests, is a result of this lack. Rather than face our incompleteness right now, we project it onto a future time, the time of our death. This future event becomes the source of our anxiety, rather than the more immediate, and therefore more terrifying, realization that we are inadequate right now, and can never be made whole.

Ultimately we long, both Becker and Loy agree, to transcend our finiteness and incompleteness. Both agree that it is through our cultural projects and products that we try to transcend death or to fill our lack. Where Becker talks about the attempt to carve out “a place in nature, by building an edifice that reflects human value,” Loy suggests we need “to organize the chaos of life by finding a unifying meaning-system that gives us knowledge about the world and a life-program for living in it, informing us both what is and what we should do.“6

Here is a story that makes sense of order and anxiety — and the anxiety of order — in existential terms. The human search for and construction of order, it says, is our response to the profound mystery, and the accompanying anxiety, of existence. Emerging into an unfathomable universe and fearing that we are nothing within it, we strive to create a meaningful and ultimately immortal place for ourselves. Like Marlon Brando’s character in On the Waterfront, we long to be somebody, “instead of a bum, which is what I am.” Culture creates the conditions for a meaningful existence, for us to play out our games of physical and symbolic survival. But it is an ongoing performance, a play we can never stop performing, lest we see the backstage gears and levers and be reminded of the mysterious and terrifying backdrop against which we are performing it. Of course we are always coming upon gaps in the play: when a loved one dies, when war makes a mockery of our pretensions to civility, when we wander into a deteriorating department store, or are awakened in the middle of the night with physical or psychic pain, or even when a messy desk threatens our ability to cope with our ordinary, everyday chores. But these failures of performance are quickly fixed or covered up or, when this isn’t possible, denied and forgotten.

Here too is where documents reenter the story For they are death-transcending, lack-filling artifacts of major proportions. Perhaps they can’t literally prevent our physical demise or fill our deepest sense of lack. But they are central participants in our attempts to do so. Every one of them — each cash register receipt, each greeting card, each Post-it note — makes a contribution to the collaborative edifice we call human culture. Although few carry the cultural weight of the Bible or the Constitution, all of them inform us of “what is and what we should do.” And in concert they help us create and sustain an orderly and meaningful human lifeworld. But all our cultural products do this, so what, if anything, makes documents special?

What makes them special, what makes them unique, is that we have created them in our own image. We are, in the language of the ancient rabbis, ha-medabrim, talking beings, and we have created ha-medabrim. We are body and breath, in the language of Genesis, and so are our documents. This perceived parallel has given rise over the centuries to a unique possibility: that we might preserve ourselves in and through our documents. Indeed, since ancient times writing has been seen as a vehicle of immortality. Writers have attempted to preserve their words and ideas, to fix them in a permanent medium, to have them resurrected in the bodies of future readers. By embedding some portion of their essence (their voice, their soul) in stone, in parchment, or in some other durable medium, the hope has been that they might live on — that they might “outlive or outshine death and decay.”

At times this strategy has been more than a metaphor. In ancient Greece, where reading was typically vocalized, to read an author’s words aloud meant to be controlled by the author. To have one’s words read meant “to take control of somebody else’s vocal apparatus, to exercise power over the body of the reader, even from a distance, possibly a great distance both in space and in time. The writer who [was] successful in getting himself read [made] use of the internal organs of someone else, even from beyond the grave.”7 From this perspective, through one’s writings, one might hope to live on through others.

Today, however, it isn’t so easy to see documents as part of a literal immortality project. We know too much. The attempt to preserve ourselves on paper or even in stone seems no more realistic than Egyptian attempts to achieve immortality through mummification. We know how fragile and short-lived is paper. We know that Web pages, for the moment at least, are likely to survive a matter of days, less than an instant in cosmic time. We know that even when words and phrases are preserved for long periods, meaning and interpretation continue to shift. Documents cannot save us — at least not in this way

Still, in their very essence, documents carry a protest against the passage of time, against change, and against human mortality. The very fact that we have tried to hold our voices and our messages fixed in stone or in some other medium is surely a testament to a powerful longing within us. The fact that we have invested so much cultural energy in the enterprise — mastering materials, creating systems of communication, teaching literacy — over so many centuries is surely evidence of the strength of this drive. And even if documents ultimately fail to solve our crisis of mortality, that they manage to achieve any measure of fixity at all in a world of continual flux is surely a remarkable achievement. Their moments of stolen fixity are like temporary steppingstones in the river of time. It is remarkable how a cash register receipt or a one-word note provides just enough stable ground to carry us the needed distance in a desired direction, then dissolves or loses its potency.

What’s more, since documents are reflections and materializations of ourselves, their stability, however brief, is an assurance of our own. By making graven images of ourselves, we keep trying to see and know ourselves, and to make ourselves real. Some of these reflections we explicitly acknowledge and accept. Many of us keep personal journals as a way of knowing ourselves by putting ourselves on paper. Other reflections we explicitly disown. Who among us wants to see the massive tangle of bureaucratic documents as reflections of ourselves, as external manifestations of our tendencies toward depersonalized control?

No arena better shows off our sense of lack — how we are, or can be, driven by it, or how documents can be used to address it — than advertising. Most straightforwardly, of course, advertisements simply promote awareness in the hope that we will be moved to act. They tell us “what is” (a product or service) and “what we should do” (buy it!). If this were all ads did, their existential roots would be clear enough. But they actually go one step further, not only telling us what we should buy, but why. And it is in this second step that they most directly play on our sense of lack. For they hint, sometimes more explicitly, sometimes less, that through our purchase we can be made more real, more whole.

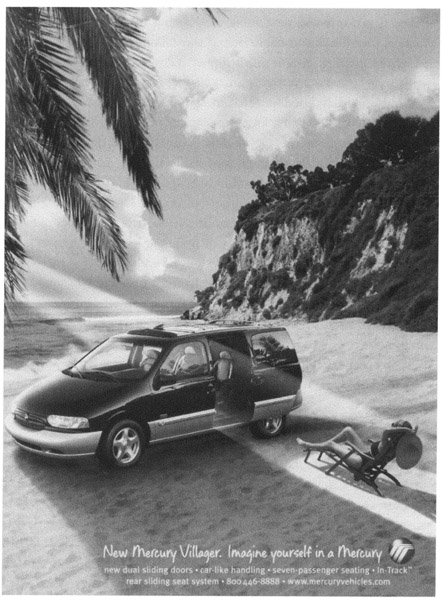

Let me illustrate with an example, an ad that appeared in magazines in the late 1990s. It shows the new Mercury Villager, a sport utility vehicle, parked on a beautiful tropical beach. As it sits there on the sand, close to the water’s edge, a woman in a bathing suit, presumably its owner, is lounging nearby in a beach chair. The ad’s message seems clear enough: Just look at the beautiful places this van will take you. (Never mind that you can’t drive from New York, or even from California, to Hawaii.)

But on closer inspection, there is something curious about the rendering. One detail seems out of place. The van is actually parked between the woman and the water’s edge. Why would you drive to the beach only to position yourself in a way that obscured your view of the water? I can think of two reasons: to shield yourself from the sun or from the wind. Yet neither of these explanations seems to work. There is no evidence of wind, and besides, the van’s sliding doors are open: a wind coming off the water would likely pass directly through them. And as for the sun, well, this woman is hardly shielding herself from it. She is basking in it, in evident delight. The ray of sunlight illuminating her is passing through the van to get to her. It enters through the right rear passenger door and exits through the left passenger door, and as it is refracted through the vehicle, its gray hue is transmuted into a golden glow.

On a literal level, this image is showing off one of the new Mercury Villager’s distinguishing features, that it has sliding passenger doors on both sides. But you’re unlikely to understand this — it’s almost impossible to read from the image — unless you already know it to be so. Something else is going on here, and it is this anomaly that points to the deeper message being conveyed. While on the surface the ad speaks of travel to beautiful places, and extra doors for easy entry and exit, its deeper message is of transformation and illumination. This vehicle won’t just take you to the beach, it will take you to heaven. It is a remarkable double offer being made here: a means of practical mobility and a route out of our fallenness.

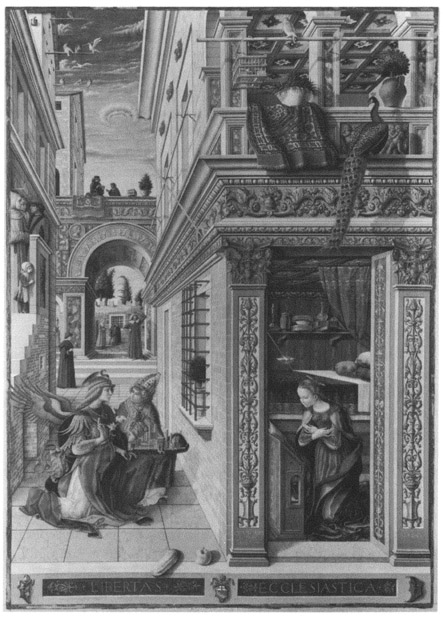

Light is a common symbol of higher states of knowledge and well-being across cultures. While it often has overtly religious overtones, its symbolic value is equally invoked in secular contexts (as in “the Enlightenment,” the name for the period of political emancipation and scientific progress in the eighteenth century). The designers of this advertisement have clearly borrowed traditional religious iconography, whether consciously or not, and have adapted it to suit their purposes in late-twentieth-century consumer culture. In Christian art, a ray of light commonly signifies the Annunciation, the announcement to Mary that she will bear a child. In Carlo Crivelli’s late-fifteenth-century painting, for example, a heavenly ray falls on Mary, piercing the wall of the room where she kneels in prayer. In the ad, where Mary has been replaced by a woman in a bathing suit, there is something almost sacrilegious about the sunbather’s suggestive pose. And yet there is something right about this too, for in her open state, she is receptive — ready to accept the light, to be transformed by what it has to offer.

Once you start looking at ads in this way, you find that many of them address our most basic human concerns. Some are even more explicit about their higher message, using text and image to reinforce one another. An ad for another large passenger vehicle shows an ocean liner with lifeboats mounted above the deck. In place of one of the boats is a Chevy Blazer. The caption reads, “A little security in an insecure world.” Surely it is a great comfort to know that we will be safe when the ship (which ship? the stock market? the planet? our life?) goes down. (Unfortunately, this powerful message of protection in difficult times is undercut, hilariously, by one small detail. In the lower right-hand corner is the Blazer logo and motto that reads: “Blazer/Like a rock.”)

As the Blazer example illustrates, not all advertisements make their appeal in explicitly religious terms. Yet in an odd sort of way, they are like prayers. Perhaps they are prayers. Certainly they are expressions of our deepest hopes and longings: to be happy, loved, safe, powerful, wise, knowledgeable; to live full and meaningful lives; to have and to be enough. Perhaps some future civilization will come upon our TV and radio broadcasts, our magazines and newspapers, our Web pages (“click here for . . .”), and will recognize the sacred quality in these fervent appeals, more so perhaps than we can now.

But I would go a step further and suggest that all our documents have a sacred quality about them, that all of them are religious in nature. For all of them, insofar as they attempt to extend our reach, to cultivate relationships, and to augment our knowledge and understanding, are responses to the mystery of existence. They are concrete manifestations of our longing to be more powerful, more connected, more in-the-know. And in this sense they are religious — not because they necessarily give voice to particular religious ideologies (although some of them certainly do), but because they arise from the same deep, existential source as do our religious traditions. Why do we want more power, more love, and more knowledge, if not because we feel we don’t have enough?

It should hardly be surprising if these same longings — existential longings, religious longings — are present in the claims for our newest technologies and our newest documents. The Web and the Internet will give us so much more of what we really want. This is the structure of nearly every claim now being made, whether in business, in education, in government, or in social and communal relations. Much of the power of these claims comes, I believe, not from the utility of the goods or services being offered, but from the deeper longing or lack being touched, and the hint that it will be satisfied. Therein lies the danger. It is one thing to buy a new Mercury Villager because you want to get your kids to the beach. But it is something else again if you spend the money in the hope of being liberated from the suffering of the world. How can we begin to separate hype from hope, without acknowledging and examining the depths of our humanity, including our fears and anxiety, and our desperate search for stable ground?