SOME YEARS BACK, I was shocked when I walked into the Saks Fifth Avenue in the Stanford Shopping Center. Instead of finding the brightly lit store with aisles full of expensive merchandise beautifully displayed — the shop I’d visited many times before — I found a dingy, rundown excuse for a store. Paint was peeling off the walls, display counters were nicked and tattered, and the merchandise was in disarray; it had a slightly used air about it. This could well have been a dream, the anxious sort where you return home to find that everything has changed. But it wasn’t. I walked outside, just to make sure I had found the right building, but also to clear my head from the shock and confusion. As I entered the building the second time, I noticed a sign I hadn’t seen the first time. The sign explained that Saks was closing and that the building was being used as a “seconds” store for Saks merchandise.

Evidently what I had encountered was a store in decline. Through their elaborate and highly tuned order (lighting, displays, music, and so on), fancy department stores like Saks try to suggest a timeless and perfect order, an effortless happiness, which can be ours if we will only buy the right things. We are never meant to see the huge amount of work that is required to maintain the illusion. I had come upon the inevitable decline that occurs when the invisible, ever-ongoing work of maintaining order is withheld. And what I experienced was not just the shock of the unexpected but a confrontation with the chaos that lies just behind the carefully maintained façade.

Of course it isn’t just stores or shopping malls that need to be constantly maintained. Everything does. Gardens go to seed, bridges fall down, clothes become frayed and stained, and human relationships wither without regular attention. The same is true for documents. Without proper care they decay, lose their intelligibility and intellectual currency, and become inaccessible. And this isn’t just true of paper documents. We are quickly discovering that digital materials, too, need to be properly tended. Web pages disappear and links break. Digital media — floppy disks, CD-ROMs, and so on — degrade after a matter of years, and the files stored on them have to be copied to new media if they are to be preserved.

These problems are only magnified and compounded when we have more than a couple of documents. For now we have to organize or arrange them in some more or less systematic fashion. There are so many places in our lives where documents tend to pool or congregate. And in each of these places we have to do something with them, if only to sift through them as needed. People’s bookcases are an obvious enough collection point. (Henry Petroski has recently written a book-length meditation on just this subject.)1 I am an inveterate browser of people’s bookshelves, always curious to see what other people have been reading, and which books they choose to display But I am equally curious about the manner in which they array them. Are their books neatly aligned, like the leatherbound books in the Levenger catalog, or do they teeter on the shelf at odd angles? Do they use bookends, or the sides of the bookcase, for support? Does there seem to be an intellectual ordering to the books (cookbooks here, travel books there)? Are they arranged by size, or is there no discernible organizing principle? (“To arrange a library,” says Borges, “is to practice, in a quiet and modest way, the art of criticism.”)

Less obvious, but equally intriguing, are peoples refrigerators. There you will find collections — unselfconscious collages — of photographs, newspaper articles, theater tickets, kids’ drawings, calendars, and all manner of flyers and announcements of future events. It may be hard to discern an ordering principle at work, but generally there is one, however partial. When you’ve run out of space on the refrigerator door, which sheets do you decide to take down first? Or if you are going to double up more than one page using the same clips or magnets, which one goes on top? Do you stack them or overlap them? Even if you don’t have a single organizing principle (such as putting the most current announcement on top), this doesn’t mean that you aren’t organizing the refrigerator’s display.

Our wallets and purses provide a different kind of collection point. Refrigerators and home bookcases tend to reside in the more-public spaces of our private dwellings. You don’t generally display items there that you don’t want others to see. Wallets and purses, by contrast, are most definitely private territory: you don’t poke around in someone else’s wallet or purse without permission unless you’ve found it in a public place and you’re trying to identify the owner, or unless you’re up to no good. Many of the materials there have a certain bureaucratic or commercial power — paper currency, credit and debit cards, and driver’s licenses. But here too you may find newspaper clippings, photos, fortunes from fortune cookies — some of the same materials you find more publicly displayed on refrigerators. Compartments of different sizes encourage at least a minimal sorting and separating by genre and function: IDs versus paper money versus photos versus tickets.

We are possessed of a remarkable range of technologies for organizing our document collections, especially those realized on paper. This should hardly be surprising, since paper has been such a crucial medium for so long. Just walk down the aisles of an Office Depot or your local stationer, and you will find a seemingly endless array of tools and devices: file folders and filing cabinets; bookcases; stacking trays for the desk; pushpins and cork bulletin boards. In some cases we have a number of alternatives to accomplish (at least superficially) the same aims. This is particularly true when it comes to keeping sheets of paper together. Do you staple them, or perhaps clip them with a paper clip (large or small, silver or colored), or with a binder clip? Do you place them in a manila file folder, in an envelope, or in a clear plastic cover? Do you punch holes in them and insert them into a ring binder? The decision may partly be an aesthetic and a personal one, but there can also be a functional component: How likely are you to want to separate the sheets, or insert new ones?

Grouping — or sorting, or categorizing, or classifying (call it what you will) — is one of the most powerful intellectual tools we have for managing our lives. It is something we do all the time. “To classify is human,” Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star say in their book Sorting Things Out: Classification and its Consequences.

We all spend large parts of our days doing classification work, often tacitly, and we make up and use a range of ad hoc classifications to do so. We sort dirty dishes from clean, white laundry from colorfast, important e-mail to be answered from e-junk. We match the size and type of our car tires to the amount of pressure they should accept. Our desktops are a mute testimony to a kind of muddled folk classification: papers that must be read by yesterday, but that have been there since last year; old professional journals that really should be read and even in fact may someday be, but that have been there since last year; assorted grant applications, tax forms, various work-related surveys and forms waiting to be filled out for everything from parking spaces to immunizations. These surfaces may be piled with sentimental cards that are already read, but which cannot yet be thrown out, alongside reminder notes to send similar cards to parents, sweethearts, or friends for their birthdays, all piled on top of last year’s calendar (which — who knows? — may be useful at tax time).2

Of all the places where documents pool and accrete, people’s desks are undoubtedly my favorite. They offer such a rich snapshot of modern life, of modern practices and pressures. Looking at one is a bit like examining a tidepool. At first it seems static and uninteresting. But once you start to pay attention, you begin to see what a complex ecosystem is present, and how much richly structured and diverse activity is going on right before your eyes. On someone’s desktop, you’re likely to see a heterogeneous mix of documents: some bureaucratic and administrative; some personal and private; some published. On my own desk right now I have three small images propped up against the wall, two photographs and a postcard. In addition, I have drafts of various chapters of this book, some in colored file folders, some loose, some stapled, some clipped. They are loosely organized into two piles, with drafts and notes for the current chapter spread out over the piles and drifting onto the bare desktop. I also have a handwritten to-do list, my Filofax (calendar), and a vertically arranged stack of bills and other correspondence still to be dealt with.

Each of these documents has its own trajectory and its own rhythm. They only appear to be static, like Zeno’s tortoise, if you look at them in the moment. Some, like the to-do list and certain chapter drafts, are just passing through, and are destined for the trash in short order. Others, like the postcard and the photos, are meant to stay for a while. Some of the book drafts will eventually make their way to my files. Other documents have an even more complex future ahead of them. The utilities bill, for example, is a composite document, and its various parts will eventually be sent off in different directions: when the bill-paying urge finally strikes, I will tear the lower portion of the bill at the perforation and send it back to the utilities company with a check in the envelope provided, while I file the upper portion “for my records” (which probably just means tossing it in a box in the closet). At the same time I will throw out the envelope in which the bill first arrived, as well as the newsletter advising me on water conservation.

But I am not interested only in the range of documents on the desktop, the strategies for organizing them, or their life stories; I am equally interested in the psychological stresses our desktops evoke in us. It is the rare person who isn’t somewhat traumatized by the state of his or her desk. People don’t seem to worry too much about the state of their refrigerators — what’s on the outside, at any rate. We don’t tend to apologize if there are lots of announcements, photographs, and shopping lists posted on the door. It’s a very different matter, though, when it comes to our desks, either at home or in the office. We are embarrassed by our own documentary clutter and mess and invoke standard jokes to express and manage our embarrassment (“a clean desk is the sign of a disorganized mind”). We judge our desks by standards that are not our own: the one obsessively neat person we know whose desktop is always tidy; the executive whose files are managed by an assistant; the professional organizations, libraries, and archives, that work, day in and day out, to keep their collections in order. But in all these cases — and in libraries especially, I believe — if you scratch the surface you will find the same anxieties of order and disorder being played out.

Libraries have been in the business of collecting, organizing, preserving, and providing access to documents for thousands of years. If we think our individual efforts are daunting, imagine the pressures on institutions responsible for overseeing thousands, even millions, of culturally significant documents. (The mission of the fabled Library of Alexandria, created more than two thousand years ago, was nothing less than to amass “the books of all the people of the world.”3 It is thought to have held as many as 500,000 scrolls.)4 Because of the scope of their enterprise, libraries have been forced to develop highly systematic methods of organization — methods that could work relatively satisfactorily for huge numbers of works, and that could transcend the skills and knowledge of particular individuals.

Central to these systems has been one simple but extremely powerful documentary form: the list. Lists were one of the earliest forms of writing, no doubt because of their usefulness in accounting and administrative practices. The anthropologist Jack Goody notes that of the clay tablets dating to the fourteenth century b.c.e. excavated in one Syrian town in 1929, the vast majority are lists: tax lists and lists of rations, occupational lists, census records, and so on.5 Much as lists could be used to keep track of people, taxes, crops, and livestock, they could also be used to keep track of documents. This seems obvious enough to us now. But I can only guess that a leap of imagination was required to realize that written forms could be used to manage other written forms.

Lists of library holdings — or catalogs (from the Greek katalogos, meaning “list”) — are therefore quite ancient. When the French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette excavated the “House of Papyrus” at Edfu in the 1860s, he found none of its contents, but still discernible on its walls were inscriptions listing the library’s holdings. This early catalog was divided in two: one list covered works on magic; the subject matter of the second — with titles like “The Book of what is to be found in the temple,” “The Book which governs the return of the stars,” and “The Book of places and of what is in them” — is harder to discern.6 For the Library of Alexandria, the poet Callimachus is said to have compiled a catalog filling 120 volumes.7 This long history notwithstanding, it is only in the last 150 years that cataloging as a systematic, professional enterprise has emerged. Indeed, the catalog produced through these professional practices, the modern catalog, is inseparable from the birth of the modern library. Both are products of industrialization and bureaucratization.

In the United States, much of the initial energy for the development of modern libraries came from the desire to supplement public education. The first public library opened its doors in Boston in 1854. The argument for it, as articulated by its chief sponsor, George Ticknor, was a lofty one. It would complement and extend Boston’s system of public education: “Why should not,” Tiknor asked, “this prosperous and liberal city extend some reasonable amount of aid to the foundation and support of a noble public library, to which the young people of both sexes, when they leave the schools, can resort for those works which pertain to general culture, or which are needful for research into any branch of useful knowledge?”8 The idea spread rapidly. By 1875 nearly two hundred publicly funded libraries had been created around the country.

The following year, a hundred librarians met in Philadelphia and formed the American Library Association. One of the central figures was Melvil Dewey. Dewey was only twenty-five years old at the time, but through his energy, ambition, and inventiveness he was already making a name for himself. While still an undergraduate at Amherst College he worked as an assistant in its library. During this time he invented the scheme that still bears his name, the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC). The DDC was an attempt to sort or group books into useful categories. Naturally there are endless ways to group books — by size, by number of pages, by authors last name — some of which will prove to be more useful than others. The DDC aimed to classify them by their content or subject matter. What makes this such a daunting task is that books can be written about virtually any subject in the world. So if you’re going to create a classification scheme for the subject matter of books, you’ve got to create a set of categories that span all of creation — at least insofar as human beings conceive of, speak, and write about it.

Dewey was hardly the first person to undertake to classify all of human knowledge. Nor was he the first to seize on such a scheme to organize books. In the early seventeenth century, Francis Bacon had created a highly influential classification of knowledge that was used as the basis for innumerable library catalogs from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century9 What seems to have been most original about Dewey’s work was the way he used a classification of books to “mark and park” them — to place them on shelves. Up to that time, books were kept in fixed locations. Dewey was struck by “the waste of time and money in the constant recataloging and reclassifying made necessary by the almost universally used system where a book was numbered according to the particular room, tier and shelf where it chanced to stand on that day, instead of by the class to which it belonged.”10 In his rethinking of this system, books were given a unique (decimal) classification number once and for all, which could be used to shelve them relative to one another. This reduced the effort required of the library staff, and made searching and browsing easier for patrons at a time when public library stacks were being opened up to the general public.

Time management was a central obsession of Dewey’s, beginning in adolescence. As the historian Dee Garrison tells it, Dewey’s relationship to time was part of a larger pattern, an obsessive-compulsive need to control the world around him.

The attempt to control all eventualities presented time as a special problem to Dewey. Time, an enemy to be overcome, was a threat to all his plans and projects. Since a guarantee of the future was his prime concern, he experienced time in the present as being wasted unless it were filled to the brim. The present did not have significance in itself because his interest was solely in the future. . . . Day after day was consumed in a futile and desperate struggle to control the passage of time itself. Unable to tolerate ambiguities and unpredictabilities, Dewey sought to dismiss time as a realistic limitation on his life. He craved certitude — desired to foretell, foresee, and exert control before the fact. Thus Dewey’s lifelong concentration on detail is best understood as a measure of self-protection.11

In the service of this vision of time-saving as a path to greater life, Dewey became an “irrepressible reformer,” in the words of another biographer, Wayne Wiegand.12 By the time he was eighteen he had already identified four time-saving crusades he would pursue throughout his life: simplified spelling, the adoption of the metric system, shorthand, and written abbreviations. (The simplified spelling of words like catalog and the naming of the New York State Thruway are directly attributable to Dewey’s influence. Dewey also changed his own given name, from Melville to Melvil.) But it is his library work that in the end was the most successful of his reformist enterprises and for which he is most remembered.

In trying to locate the magnitude and significance of Dewey’s work for his time, Francis Miksa, a professor of library and information science at the University of Texas, resorts to the language of our times. He casts Dewey as a savvy businessman, an entrepreneur: “But the fact is the DDC was an entrepreneur’s dream, a brilliant invention which would have thrilled anyone who had a business sense and appreciated the value of innovation. It was like an 1870s DOS or Netscape in that it did something that no one else had ever successfully done before — it organized books in a reasonably efficient way in libraries.”13 This was clearly a major achievement in itself. But Dewey also played a central role in establishing librarianship as a profession. He had a strong hand in the formation of the American Library Association and its journal, the Library Journal He founded the first library school in the country, at Columbia University in 1887, which was groundbreaking not just because of its subject matter but because he insisted on admitting women to the program.

Dewey also founded the Library Bureau, a commercial venture, in 1882, to develop and sell equipment to libraries and businesses. A few years ago I was lucky enough to stumble upon a copy of the 1909 Library Bureau catalog in a secondhand bookstore. (By coincidence, it was discarded from the library of the college I attended as an undergraduate.) It contains highly detailed illustrations of the equipment they sold. Nearly all this equipment is instantly recognizable as the equipment we’ve seen and used in public libraries: cabinets with long drawers to hold catalog cards; library tables, benches, and chairs; inkstands, paperweights, and stamps; and a whole range of paper forms, including the “borrowers’ cards” stuck in the backs of library books to record when books were borrowed and returned.

The Library Bureau sold practices as well as products. Imbued with Dewey’s missionary zeal, it aimed to teach libraries how to create vast efficiencies through the use of its equipment. In the opening paragraphs of its 1909 catalog, it makes clear that it views order or organization in the service of users as the central function of the library:

The development of library science during the last quarter century has made it evident that a library in the true sense is not merely a certain number of books, but rather a collection of books so arranged that they may be conveniently used for reading or reference. Five thousand well-chosen volumes classified and administered according to modern methods may better deserve the name of library than four times the number carelessly or erratically arranged, even though the larger collection might contain every volume to be found in the smaller group.14

If Dewey isn’t better known outside the library profession, it is perhaps because of a number of personal flaws that offset his genius for organization. He was intense, arrogant, driven, and possessed of an exaggerated moralism. He was racist and anti-Semitic. He could be duplicitous. And “he crafted into the normal practices of institutions he created the striking character flaws and social prejudices he himself embodied.” “That there is so much to dislike about Melvil Dewey’s character,” says Wayne Wiegand, “may explain why his legacy has been under-studied in recent decades.”15

Yet despite all this — or perhaps because of it — there is something mesmerizing about Dewey He made a deep impression on people. A schoolgirl who met him in 1892 described her impression on being ushered into this office. Observing him, “[i]t was like watching a fine machine, an electric machine — the air about him was vibrant with energy. . . . His decisiveness, the sparkling darkness of his face (dominated by his vivid eyes), his intense energy impressed me deeply. Indeed, I was a little awed ... I had come into contact with an immense force.”16 And more than a hundred years after this observation, the force of his crazy brilliance still attracts notice. For Dee Garrison, he is to be studied for what he can teach us about a certain type of personality, a “reforming ‘savior’ mentality.”17

My own fascination with Dewey comes from a somewhat different angle. On the one hand, I see him as a product and symbol of his age. He lived through a period that worshiped the god of efficiency and created bureaucratic systems of control on a scale and to a degree that were previously unimaginable. With his exaggerated fears and anxieties, and his enormous energy and intelligence, he represents that spirit well. But at the same time that he speaks from and for this particular era, he also embodies a response to life that is found in all of us to varying degrees. For there is, it seems to me, a degree of anxiety embedded in all our attempts to order and organize, to control the world around us. The discomfort we feel when faced with our disorganized desks, our cluttered offices, our messy homes, is emblematic of a more general aversion to mess. Here is how I understand this.

Clutter or disorganization, first of all, alerts us to real, often immediate problems in our lives. The cluttered desk speaks of the amount of work awaiting us, the sheer volume of it. And the fact that the desk’s contents aren’t better organized speaks of a lack of time and attention. (With more time and attention, we would get better organized, wouldn’t we?) Who wouldn’t be anxious when faced with too many tasks to do, in too little time? What’s more, because we aren’t better organized, we are likely to work less effectively. Who wouldn’t feel terrible when being strangled by paperwork?

There is ample reason, then, to see mess — or clutter, or disorder — as a signpost pragmatically alerting us to trouble ahead, like a road sign warning about icy road conditions. But I think there is more to it than that. My sense is that the anxiety provoked by disorder is intimately connected with some of our most basic fears about survival and well-being. As human beings, we seem to crave order as much as we crave anything in life. With our minds — through the pursuit of science and religion, for example — we seek to discover a larger, meaningful order in the universe. And through our actions, we are continually working to create orderly patterns of behavior. Human culture, human society is the collective enterprise by which we establish and maintain shared understandings and ways of behaving. Laws are a big part of this, as are ethical systems of conduct, codes of politeness, and group norms. To live with others is to participate in making, living out, and policing individual and collective conduct.

There is clearly survival value in such practices. Without guidelines for behavior that aim to minimize conflict and to manage it when it arises, great harm can come to individuals and to entire groups. We have only to look to the former Yugoslavia, or to Africa, to see what happens when dark destructive human tendencies take precedence over orderly conduct. Or we have only to look to the scenes of natural disasters to see how illness can achieve epidemic proportions when human-created systems of water purification, food storage, and burial are disrupted.

At times, it seems that human cultural order is no more than a thin veneer overlaid on a much wilder, uncontrollable, unknowable, and dangerous world. To the extent that this is so — to the extent that we live with this sense, however unconsciously — then order-making will be tinged with anxiety. And what makes the process of order-making all the more charged is the knowledge that it must continually be kept up. Rundown barns in the countryside, roadways with potholes, the state of our homes when we’ve neglected our cleaning duties, all testify to the decay that befalls any human enterprise that isn’t continually maintained. Is it so farfetched to see our messy desks as silent reminders of the chaos that lies just beyond the trim lawns and cultured sensibilities of civilized life?

And so I see Dewey as a kind of anti-Whitman. The man portrayed in Whitman’s poetry — “Walt Whitman, a kosmos” — is the great embracer of life. Far from needing to regularize or standardize or control it, he takes things as they come. The world is enough just as it is; there is an order, a logic to it, just as it is. Even death is to be accepted, celebrated. But for Dewey, the world must be shaped, bent, controlled. Far from accepting death, Dewey was terrified of it. “[T]he central key to an understanding of Dewey’s personality is his over-riding preoccupation with death and the passage of time,” Garrison says. This she sees as a characteristic of the obsessive personality. “The obsessive feels besieged, at every moment. The forced drivenness of his existence is to him a real life-and-death matter and if he does not do as he is driven to do, he is filled with panic. Dewey behaved as if his existence were continually threatened; he seemed to live in an imaginary jungle where the threat of death necessitated a constant guard.”18

It is a curious fact that both Whitman and Dewey are known for their catalogs. Whitman’s are free-flowing celebrations; their logic is that of the ecstatic witness proclaiming what he sees. In “Song of Myself” (my childhood copy), he takes note that:

The pure contralto sings in the organ loft,

The carpenter dresses his plank, the tongue of his foreplane whistles its wild ascending lisp,

The married and unmarried children ride home to their Thanksgiving dinner,

The pilot seizes the king-pin, he heaves down with a strong arm,

The mate stands braced in the whale-boat, lance and harpoon are ready, . . .

(He continues like this for nearly two pages.)

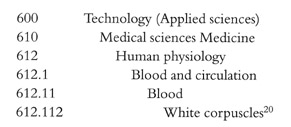

Dewey’s catalogs, by contrast, are carefully constrained works of bureaucratic order. Dewey, says Garrison, “had realized the obsessive’s dream — to place all of human knowledge into ten tight holes.”19 He created a system for manufacturing carefully constrained catalogs. Here is what a small section of his classification scheme looks like (a hierarchy of subject matters and the decimal numbers associated with them):

I am not so concerned with whether Whitman the man actually lived his idealization or simply performed it. Nor with whether Dewey was as obsessively compulsive as Garrison makes out. What interests me most is the tendencies these men exemplify: one toward observation and acceptance, the other toward control and reform. Surely all of us possess both tendencies, in different combinations and to different degrees.

Thanks to Whitmans gift and inspired efforts, we have access to a particular mystical vision of the fullness of life. Thanks to Dewey’s gifts and inspired efforts (and the efforts of many others along with as well as after him), we can identify all the editions of Whitmans work and locate copies of them. Whitman begat Allen Ginsberg, Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and many others. Dewey begat a huge network of libraries and librarians. In the United States alone there are 9,000 public libraries, 3,500 academic libraries, and 10,000 so-called special libraries. In most of those institutions there are reference librarians devoted to helping patrons find just what they’re looking for: a particular book, books on a particular topic, information needed to solve some problem or other. And hidden from normal view, from patrons’ eyes, are catalogers and other “technical service” professionals, doing the ongoing work of collection development, cataloging, and so on.

Lately, however, the continued existence of this whole institution has come into question. The buildings the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie built, the systems Dewey invented, the ongoing efforts of many thousands of librarians, are now threatened by the latest technical innovations and by new types of materials, digital materials. But why threatened, you might ask. In one sense the latest digital technologies are a boon to libraries. Online catalogs and collection management tools hold out the possibility of improving library service: helping libraries keep track of their collections and make them available to patrons. Using scanners to read the bar codes in books, just to choose one specific example, greatly simplifies the process of checking out books, to the advantage of both library personnel and library users.

What’s more, libraries have successfully accommodated to new materials in the past. Systems and practices first set up to handle books have been expanded to accommodate maps, serials (newspapers, magazines, and journals), microfiche, film, audiotapes, videotapes, and computer software. Not only have libraries been able to incorporate new materials, they have also met the challenge of incorporating new technologies — electric lights and ventilation systems in their early days, as well as typewriters, microfilm viewers, film projectors, computer workstations, and so on.

So, in one sense, the new digital documents are just another in the series of materials needing to be cataloged and made accessible. But in another sense, they seem to threaten the entire edifice, literally and figuratively it is just possible that something bigger is afoot this time. The talk now is of digital libraries, perhaps as a replacement for the traditional, bricks-and-mortar kind. Many questions are now being asked: Will we really need more library buildings, essentially huge warehouses for books, at a time when digital materials can be stored so very compactly? Do we really need separate library institutions, for that matter, when the Web is, or gives evidence of becoming, a global library without walls? How necessary are cataloging and the library’s other traditional order-making functions in this new environment? And what exactly are digital libraries, anyway? No one is quite sure.

Francis Miksa divides library history into eras. He calls the current era, which began in the mid-nineteenth century the “modern library era,” and he cautions against thinking of “the library” as a unitary phenomenon across time. “[L]ibrary historians,” he points out, “typically assume a continuity in the history of libraries that goes back much further than a century or so (some going back to Mesopotamian civilization).”21 Certainly all libraries have features in common, including collections of documents and catalogs of some sort or other. But,

were we able to jump back in time to any but the most recent manifestations of the library — for example, to libraries before 1850 or so — the further back we traveled, the more uncomfortable we would find ourselves in calling what we found at any one point a library. Our discomfort would arise from using the modern library as a standard for measuring libraries of the past. I do not simply mean discomfort with the infrastructure of the library, although that would be a factor. Rather, I mean discomfort in terms of “subjective” differences — for example, that such agencies would not have the “feel” of the modern library, that they would not go about their business in the same way, that they would not have the same sense of goals.

The modern library, Miksa suggests, is the product and the expression of particular, time-bound social conditions. The modern library — and here he means the academic and the research library as well as what we have come to call the “public library” — came into being as a public institution, publicly funded and committed to making information broadly available for the sake of society. In the service of this mission, it drew on the philosophy and methods of modern bureaucracy.

Miksa believes we are now entering a new library era. The public space within which the modern library operated, and which it helped to sustain, is closing down. In its place will come private libraries. Thanks to computers, the Web, and who knows what else, we will all be able to create our own private “libraries in a box,” with collections tuned and organized to our own specific needs. “Only a little reflection will show,” he says, “that this new kind of library is not only a denial of the modern library’s public space and general target population orientation, but it actually represents something of a return to the library era that preceded the modern library, when a library generally represented the private space of an individual or of a small group. Frankly, this reversion makes eminent sense to me for, ultimately, is not an excellent library one which is as personal in its selections and access mechanisms as the personal nature of the information seeking that prompted it?” Of course, we are likely to need help in creating such libraries and organizing them. Enter the librarian, who in the future, Miksa suggests, “will function primarily as an enabler, as a person who can help others create their own personal-space libraries, who can help families make their own family-space library systems with individual modes for family members, or who can help businesses create any one or more necessary personalized information systems.”

These are certainly provocative words, and there is much here to question and debate: Must new kinds of libraries necessarily replace older kinds? (Surely private libraries continued to exist during the modern library era. Could we perhaps agree that private libraries will increase in number without assuming that libraries as public institutions will disappear?) Is the loss of public space and public funding inevitable, as Miksa makes it sound, or would it be a consequence of choices made explicitly or implicitly in the political realm — choices that we might have a say in?

What I find most useful about Miksa’s analysis is the attention he directs to the word library and to the multiple societal conceptions that it can name. In the modern library era, the term has come to evoke a particular kind of social institution (one committed to providing communal access to information) that is realized by a particular organizational structure (the modern bureaucratic organization). As Miksa makes clear, this is a highly time-bound notion. Yet alongside this is a notion of libraries that is common across all eras: the notion of a collection. When Miksa talks about personal or private libraries, this is essentially what he means: personal or private collections.

This ambiguity between institution and collection is carried through in the phrase “digital library.” For some groups, most notably librarians, the phrase refers most directly to institutions that oversee digital collections, while for other professions, primarily computer and information scientists, it refers to digital collections, without regard to the institutional settings (if any) in which they might be managed. (Notice that the phrase “software library” means a collection of computer programs or routines, and makes no reference to an institution.) Digital library, it seems to me, draws much of its power from this ambiguity: it provides a name for collections of digital materials that invokes the aura of the modern library and its social mission (library as social institution). But it does so without actually making any commitments to the public good (library as collection).

Library, however, carries yet another common meaning, which doesn’t resonate in the phrase “digital library.” A library is also a building — one that houses collections and the staff who tend them. In the modern library era, this sense of library is also rich with cultural commitments, for the library building is a public space in which citizens are guaranteed not only access to information but a space in which to read, write, and reflect. It is a shared sacred space held open through secular civic funding and participation.

It is by no means clear what will happen to libraries, in any of these senses. What is clear, however, is that digital materials will need to be ordered and organized. There is no getting away from this kind of invisible work, whether in department stores, in our offices, or in our homes. Someone has to do it. What also seems clear is that new methods of organization will be needed, methods that are unlikely to be simple extensions of those Dewey and his contemporaries concocted more than a century ago. Whether traditional libraries (or traditional librarians) develop and implement these methods seems less important than that this all-important work be done.

Roger Chartier has observed that after the invention of the printing press it took an “immense effort motivated by anxiety” to “set the world of the written word in order.”22 It seems likely that we are at the beginning of a new immense effort, one surely motivated as much by anxiety as by excitement and fascination with new possibilities. This anxiety is broadly felt: by individuals concerned about the future of their livelihoods and by the loss of familiar, stable practices and artifacts; by institutions no longer certain of their missions or the means of fulfilling them. It is the messy-desk syndrome, an anxiety of order, but on a national, perhaps even a global, scale. The messy-desk analogy, however, breaks down in one important respect. Even when our desks have become desperately disorganized, the materials on them still have a stable and recognizable nature. But in the current transition, the new materials are still being formed — the clay is still wet. What sense can we make of this new cyber-substance?