My son, you are predestined! You will realize that artistic goal whose spell bewitched my youth in vain.

ADAM LISZT1

The year 1811 was momentous. All Europe was in turmoil. The Napoleonic Wars had been raging for nearly a decade and had left a trail of devastation behind them. Napoleon himself was still at the height of his powers, his most terrible battles yet to be fought. He raised a grande armée of half-a-million men and marched on Russia. The Russians turned and fought at Borodino on September 6, and there was a bloodbath: eighty thousand casualties littered the field. Napoleon finally took Moscow on September 14, 1812. The Russians then set fire to the city, making it impossible for him to establish winter quarters there. Now began the arduous, thousand-mile trek back to France. The first snows fell in October; by early November the hard frost had set in. On November 6 Napoleon marched with his army through a blinding snowstorm at minus 20 degrees centigrade. His columns were constantly harassed by the Cossacks. Under the command of General Kutusov, the Russian army resorted to guerrilla tactics, striking swiftly and disappearing, often with prisoners. An English observer with General Kutusov saw sixty dying men, stripped naked, their necks laid upon a felled tree, while Russian men and women with large sticks hopped around them, singing in chorus, striking out their brains with repeated blows.2 The stragglers from Napoleon’s columns were lured into Russian huts with promises of warmth and food, only to have their throats cut. The lucky ones were those who simply fell asleep in the snow and froze to death. Entombed in thick ice, they lay there until the following spring. Then the Russian thaw set in. Thousands of corpses, locked in macabre positions, were now revealed along the routes from Smolensk to Warsaw, silent sentinels to this epic tragedy. Eastern Europe had become one vast graveyard. Of the grande armée’s half-a-million men, only fifty thousand succeeded in getting back to France.

To the south things were easier. In 1810 Napoleon had married the Archduchess Marie Louise, eighteen-year-old daughter of the Emperor of Austria. Within a year she had borne him a son, who was proclaimed King of Rome. This alliance between the Habsburgs and France protected Napoleon’s southern flank and brought a temporary stability to the area. But even here, in the cities of Vienna and Munich, Prague and Pressburg, a social phenomenon had emerged on a scale unparalleled in Europe’s history. The maimed survivors of the great battles of Austerlitz, Jena, and Eylau had started to trickle back home. They would soon be joined by the wounded soldiers of Borodino, Leipzig, and Waterloo. Wherever one turned, the battle-scarred veterans of the Napoleonic wars could be observed with their missing limbs, eyeless sockets, severed ears, and jagged sabre wounds across the face and hands. These old campaigners were a constant reminder of Europe’s agony, and many of them lived into the 1850s and beyond.

Presiding over these grisly scenes, like a ghostly galleon in the skies, was the Great Comet of 1811, one of the astronomical wonders of the age. This astonishing phenomenon illuminated the night skies of Central Europe. Men gazed heavenwards, awestruck by the wondrous sight. They took it to be an omen. Napoleon had actually consulted astrologers and planned his disastrous military campaign against Russia convinced that the comet foretold a great victory for him. The spectacle gradually waxed in intensity, until night was turned to day. By the middle of October the comet’s tail was estimated to be at least 100 million miles in length. During the previous August, the tail had divided into two streams, almost at right angles to one another, and it now left a brilliant carpet of light spread across the entire northern hemisphere.3 Eighteen eleven was a year of ghastly horrors, but brilliant portents. Its greatest son was Franz Liszt.

Immediately after their wedding Adam Liszt and his young bride, Anna, set up house at Raiding, where, as we have seen, Adam had been intendant of the Esterházy sheepfolds since 1809. In those days Raiding was a major sheep-breeding station for the Esterházys, and its combined flocks numbered more than fifty thousand.4 Adam, with his clerical training and his flair for organization, quickly became one of the Esterházys’ trusted employees. Since the sheepfolds were widely dispersed, Adam used to conduct his inspections on horseback. He became a familiar figure during these visits to the surrounding villages, and he built up a wide circle of friends and acquaintances. The family home was a low-lying, whitewashed brick dwelling with tall chimneys, on one level, possessing a courtyard at the front and a small orchard at the back. It stands in Raiding to this day and is indistinguishable from thousands of similar dwellings spread throughout Austria and Hungary. Adam and Anna were to live there for twelve years.

In February 1811, three or four weeks after her marriage, Anna became pregnant. Shortly afterwards occurred the first sighting of the Great Comet. The heavens became more spectacular with every passing week of Anna’s term. From time immemorial such marvels have been interpreted as the harbingers of men of destiny; and so it was here. The Tziganes encamped outside Raiding foretold the birth of a great man. The point is not the truth or the falsity of the prophecy; the point is that Anna heard it and later related it to her young son, and this gave him a sense of destiny which he carried with him to the grave. Anna herself was never in doubt that her child was a “chosen one.” Four months before Liszt’s birth, she fell down a disused well on the Esterházy estate.5 It was the height of the summer, and that fact probably saved her from drowning, since the water-level was low. She was brought up soaked and bruised, but none the worse for her experience, which she herself characteristically interpreted as a lucky sign. Right up to her confinement, however, there was anxiety that her pregnancy might have been affected; but the child was born without complications in Raiding on Tuesday, October 22, 1811. Anna never conceived again; Franz Liszt was to remain her only child.6

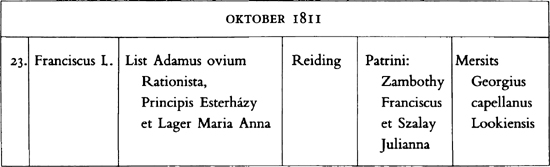

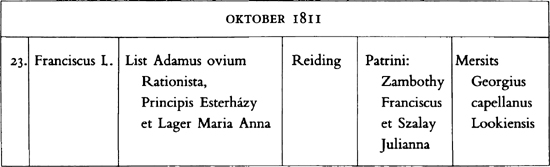

Liszt was baptized the next day at the neighbouring village of Unterfrauenhaid, since there was no priest in Raiding,7 and the details of his birth were entered in the church registry there. The baptismal certificate tells us that Adam Liszt named his son Franciscus,8 christening him after the Franciscans and also after his godfather, Franciscus Zambothy. The certificate reads

Adam himself is described on the document as an “ovium Rationista,” that is, a sheep accountant. During the baptism service, the infant Liszt was carried to the font by Frau Frankenburg, the mother of the Hungarian writer Adolf Frankenburg, who became a childhood playmate of Liszt’s.9

As an infant Liszt was weak and sickly. According to his father, the child was attacked by “nervous pains and fever, which more than once imperilled his life.”10 The low-lying marshlands of the Neusiedlersee were a continual source of infection, and the infant mortality rate in this area was high, as a glance at the Liszt family tree shows. Adam had the boy vaccinated, an advanced and radical treatment in those days.11 On one occasion, just before his third birthday, the sickness reached a crisis: the symptoms resembled those of catalepsy. The parents took him for dead and ordered his coffin made by the village carpenter. He rallied shortly afterwards, but for much of his life he was subject to feverish attacks and fainting spells.12 Liszt was nursed through this grave illness by his aunt Therese, a younger sister of Anna’s, who, in Liszt’s own words, rescued him from death.13 The boy was taught to read and write by the village schoolmaster, Johann Rohrer. Rohrer was not the village priest, an error still perpetrated in the Liszt literature. The year that the young German-speaking teacher of twenty-two was appointed as Raiding’s schoolmaster, there were sixty-seven children registered in the little school: fifty-two boys and fifteen girls. Liszt attended classes with all the other children. Rohrer taught them in a schoolroom measuring approximately 20 feet in length and 14 feet in width.14 Liszt’s general education was neglected, therefore, and he always regretted it. He once told Lina Ramann that in his childhood he had no idea of history, of geography, or of the natural sciences.15 And in a letter to Princess von Sayn-Wittgenstein he confessed that his poor primary education had always been a handicap to him, and that he had never been able to remedy this capital defect.16 We have already observed that Liszt’s parents, like thousands of other western Hungarians, were German-speaking, and that Raiding itself was a German-speaking village. Liszt therefore grew up unable to speak Magyar.17

The first few years, then, were difficult ones for Adam and Anna. Until recently, we knew virtually nothing of their married life in Raiding. Much new information has meanwhile come out of the Esterházy archives, and today we have a clearer idea of the hardships they endured. Adam’s greatest concern at first was his maverick father, Georg, who had moved with his entire family into their small dwelling at Raiding in July 1812 and stayed there for almost an entire year. We learn that Adam was rebuked by the intendant at Eisenstadt for expropriating large quantities of brushwood, manorial property, to use as firewood during the severe winter of 1812.18 Adam explained that his father’s large family was living with him, and they would all otherwise have frozen. The orchard and garden also presented difficulties. The French troops garrisoned near Raiding broke in and caused damage to the fence and the trees. Adam subsequently tried to get the prince to agree to a reduction on his lease.19 Not the least of Adam’s problems concerned the house itself, which was damp, and which eventually ruined his piano. He was forced to sell some of his personal possessions in order to buy a new one, which cost him 550 forints.20

There was a brighter side to the picture, however. Adam held frequent chamber-music evenings in his house at which he and his friends from neighbouring communities took part. Adam was not only an amateur cellist and pianist, but he also played the violin and had a good bass voice.21 Occasionally a distinguished visitor would come down from Eisenstadt and raise the proceedings to a more professional level. Adam knew all the orchestral players at Eisenstadt, about 30 miles away, and Kapellmeister Fuchs, Hummel’s successor there, often turned up at Raiding.22 The young Liszt was surrounded by music from his earliest years.

The boy’s musical genius first asserted itself in his sixth year. One day he heard his father playing Ries’s Concerto in C-sharp minor and was captivated by it. That same evening, the child spontaneously sang one of the themes of the concerto from memory. His father considered the feat so exceptional that he made him sing it again. Here is an account of that occasion, recorded by Adam in his diary, together with some observations on his son’s sickness:

After his vaccination, a period commenced in which the boy had to struggle alternately with nervous pains and fever, which more than once imperilled his life. On one occasion, during his second or third year, we thought him dead and ordered his coffin made. This agitated condition lasted until his sixth year. In that same year he heard me play Ries’s Concerto in C-sharp minor. Franz, bending over the piano, was completely absorbed. In the evening, coming in from a short walk in the garden, he sang the theme of the concerto. We made him sing it again. He did not know what he was singing. That was the first indication of his genius.23

According to Adam, the boy now incessantly begged to be taught the piano. Adam’s reluctance stemmed from his concern over his son’s delicate health. Having nearly lost him once, Liszt’s parents were resolved to spare the boy any physical strain; throughout his childhood they were watchful and protective. Eventually, Adam took on the task of giving the boy regular lessons. However, after three months’ instruction, he tells us, the fever returned, obliging them to discontinue. When they resumed, it was evident that the boy was uniquely endowed, and he started making astonishing progress.

We have hardly any documentary evidence about the lessons themselves. Adam Liszt was well qualified to instruct his son in the rudiments of piano playing, however. And he did more than merely teach him the names of the notes and how to read musical notation. He encouraged the boy to play from memory, to sight-read, and above all to improvise, skills at which he soon became phenomenal. Adam, who had a broad musical background, was familiar with a wide range of repertoire, including much of the keyboard music of Bach, Mozart, Hummel, and early Beethoven. We know that he introduced Liszt to their works, for he was prepared publicly to exhibit his son playing them. There was a special affinity with Beethoven. Whenever Liszt was asked as a boy what he wanted to be when he grew up, he pointed to the wall where a portrait of Beethoven was hanging. “Ein solcher,” he used to reply. “Like him.” It is to Adam’s credit that once he had recognized his son’s genius, he allowed it to blossom without hindrance. He himself tells us that the boy’s practice sessions were quite irregular until his ninth year,24 an indication that Adam was not the harsh disciplinarian some observers have claimed.25 Adam Liszt was also intelligent enough to know his own limitations; a teacher would one day have to be found who was worthy of his son’s gifts.

There is a touching anecdote dating from this period, little known to Liszt’s biographers. Adam regularly had his son accompany him on his travels round the Esterházy estates. He used to like to introduce his boy to his musical friends on these trips, and the precocity of “der junge Künstler” was soon widely recognized. As a special treat for his seventh birthday, on October 22, 1818, the small boy was allowed to travel with his father to Lackenbach, where Adam had some business with a wealthy merchant called Ruben Hirschler. The daughter of this merchant, Fanni, had just been given a piano, recently arrived from Vienna. Adam requested the girl to play something for his young son, who, he explained, also loved music. When the lad heard the playing he could say nothing, his eyes filled with tears, and he threw himself weeping into the arms of his father. This scene so moved the elderly merchant that he gave the piano to the boy. It was a wonderful birthday gift. Hirschler’s gesture created a warm friendship between the two families. The Liszts often used to drive over from Raiding to Lackenbach (about half an hour’s journey) and spend their Sunday afternoons in the Hirschler household.26

Another family with whom the Liszts were friendly was the Frankenburgs. Antal Frankenburg, like Adam, was an administrator on the Esterházy estates. The Frankenburgs lived in Deutschkreuz, about 7 miles from Raiding. Adam and Antal visited one another frequently. Antal, like his “cousin Adam,” as he affectionately called him, was a passionate Hungarian. He often cursed the Austrian government in Vienna and refused to attend the German-speaking theatre, saying that although his name was German, his heart was Hungarian. Adolf, his gifted writer-son, was an exact contemporary of Franz Liszt, and the two small boys became friends. Many years later, long after he had become a well-known author, Adolf wrote a reminiscence of these early years.27 Frau Frankenburg, enthralled by the phenomenal progress of “Franzi,” wanted to put Adolf to the piano as well. But he tells us that his childish mind was frightened by the huge keyboard, because he thought that innumerable tiny demons lived in it and would shoot up from the ebony keys to bite into his fingers. Instead of the piano, he eventually settled for the guitar, which appeared less threatening.

About this time, Franz narrowly escaped serious injury. Adam used to store gunpowder in the house for use on the estate—for tree felling, for hunting, and for defending the sheepfolds against natural predators. The boy used to watch, fascinated, as his father filled his leather gunpowder pouch with this magical substance, primed his gun, and went out on hunting trips. He quickly noticed that only a tiny amount of powder was required to produce an enormous bang, an event which invariably caused him great pleasure. He could not help wondering what might happen if the entire contents of his father’s gunpowder pouch were emptied on the old kitchen stove, in which Anna always kept a fire brightly burning. He waited until Adam and Anna were outside, took the pouch, and threw it into the stove. A tremendous explosion shook the house, and half the iron stove was blown out. Franz was knocked to the floor by the blast, a fact that probably saved him from the flying debris. When Adam rushed back into the house and surveyed the destruction, a suitable chastisement was at once carried out. Liszt never forgot the incident, and when he revisited his birthplace in 1881 it was the old stove, which still bore its telltale scars, that brought this memory vividly to life.28

Among the influences which were already working on the child’s character during these early years, two call for special mention. The first was the church. Liszt never lost the faith that he won for himself as a boy through his prayers in the tiny churches of Raiding and Frauendorf.29 From the outset, he was a deeply religious, mystical child. Nothing seemed to him “so self-evident as heaven, nothing so true as the compassion of God.”30 He dreamed himself incessantly into the world of the saints and the martyrs. Under Adam’s guidance, he became familiar with the forms of worship and the symbolic ritual of the Catholic faith. He knew, of course, that his father had once dedicated himself to the priesthood. More than once Adam was to take the small boy on a nostalgic trip to the Franciscans and their monastery and point out the place where he had experienced his first religious crisis. These powerful memories never left Liszt; they were to surface many times in later life. In his adolescence he would beg to be allowed to enter a seminary in Paris and die the death of the martyrs. Later still, aged fifty-three, he would finally take holy orders. To interpret such a solemn act, as so many of Liszt’s “romantic” biographers have done, as an escape into the refuge of a monastic cell in order to avoid capture by his Egeria, the Princess von Sayn-Wittgenstein, is to reveal scant acquaintance with his earliest years. Liszt’s life must be seen whole. The church, as he himself acknowledged, was his vocation almost from the start.31

The other influence was equally hypnotic. Among Liszt’s most colourful childhood memories was the image of the wandering tribes of dark-skinned Gypsies who trekked back and forth across the plains of Hungary, remarkable people whose customs, language, and music he later described in such vivid detail in Des Bohémiens et leur musique en Hongrie. The very best passages in that book are autobiographical; they are first-hand, eye-witness accounts of this proud, nomadic race, and they could have been written by no one but Liszt.32 The Gypsies entered Hungary from the Balkan Peninsula as early as the fifteenth century. They flourished there simply because they were not subjected to the terrible persecutions which decimated their numbers in Russia, Poland, Turkey, and other less tolerant countries. By the nineteenth century, tens of thousands of them were living in Hungary side by side with the Magyars, although culturally quite separate from them. The Gypsies often camped outside Raiding. Liszt describes how they would form their caravans into a large circle and unfurl their tents. The women would start small fires for the cooking pots while the men would feed and water the horses. Small groups would then enter the village to barter their handmade goods, beg for necessities, and tell fortunes to the suspicious villagers. At nightfall they would build a huge fire in the middle of their encampments, around which singers and dancers would perform. Theirs was a purely improvisatory art. Responding entirely to feeling and emotion, they would sway back and forth to the music, as if under a hypnotic spell.

What Liszt admired in Tzigane music was its improvisatory, impulsive nature. It coincided with his own view of the art as something fundamental to mankind. Here was a living proof, for him, that music was truly innate, for it had been preserved within an ancient people who had received no formal instruction whatever in the art, who could not read music notation, who were illiterate by the civilized standards of the day, and yet whose music had somehow managed to survive across the generations.

The Tziganes, in fact, produced some outstanding musicians. One of the very best, and one who made a powerful impression on the young Liszt, was the Romany violinist János Bihari.

I was just beginning to grow up [wrote Liszt] when I heard this great man in 1822.… He used to play for hours on end, without giving the slightest thought to the passing of time.… His musical cascades fell in rainbow profusion, or glided along in a soft murmur.… His performances must have distilled into my soul the essence of some generous and exhilarating wine; for when I think of his playing, the emotions I then experienced were like one of those mysterious elixirs concocted in the secret laboratories of those alchemists of the Middle Ages.33

Bihari formed one of the finest Tzigane bands of the day, in which every player was a virtuoso, and between 1802 and 1824 they toured Hungary, Transylvania, and Austria in their colourful national costumes. They internationalized the friska and the csárdás. One of their favourite renderings was Bihari’s fiery arrangement of the Hungarian Rákóczy March, a melody he was once reputed to have composed. (This was impossible, since Bihari, true Gypsy musician that he was, could not read, let alone write music notation. We now know that this old Hungarian melody was not written down until 1820, by Michael Scholl, the military bandmaster of the Esterházy regiment in Pest.)34 Bihari’s band once played in Vienna before the emperor, who was so moved by their exotic music that he asked Bihari what he would like as a mark of the Imperial favour. Bihari asked for patents of nobility for his entire Gypsy band! In 1824 the coach in which he was travelling overturned and he broke his left arm. This effectively ended his career, and his band dispersed. Bihari was only fifty-eight when he died in 1827, leaving a widow and an only child in impoverished circumstances, having lavished all his wealth on others during his lifetime. Liszt writes with affection about Bihari’s musical personality and has some penetrating things to say about this Romany’s life and art. When, in the 1840s, Liszt composed that national epic, the series of fifteen Hungarian Rhapsodies, he must have had constantly before him these childhood scenes and attempted to enshrine them in those unique creations.

These twin influences helped to shape Liszt’s character for life. The child was father to the man. After his death, Liszt’s biographers became fond of diagnosing his character with the damaging phrase “half Gypsy, half Franciscan”—as if to say that neither half was genuine because of the presence of the other. They could never understand how it was possible for one man to embrace both worlds and concluded that Liszt was therefore “a personality at war with himself.” Whatever else he was, Liszt was loyal to his background, to the country that bred him, and to the culture that nourished him. For the rest, that simple catch-phrase “half Gypsy, half Franciscan” does not have the merit of originating with Liszt’s biographers themselves; that is, it is not based on a study of his early background at all. They merely appropriated it, without acknowledgement, from Liszt. Half in jest he had once written: “I can be described rather well in German: Zu einer Hälfte Zigeuner zur andern Franziskaner.”35 He was visiting Hungary at the time, and rehearsals for his Graner Mass were in full swing at the great cathedral of Esztergom. During a brief respite Liszt had returned to his apartments to deal with some correspondence. Unexpectedly the father of Reményi (the violinist) had walked into his room and interrupted the narrative. His presence there later reminded Liszt to write that after a visit to the theatre that evening, he was rushing off to hear the Tziganes—“you know what particular fascination this music exercises over me.” Liszt, then, was merely describing his itinerary for August 1856, not analysing his character, which was simultaneously bringing him into contact with the sacred and the secular, clerics and Tziganes. If Liszt had not bothered to write that letter, the “Zigeuner-Franziskaner” phrase would never have been uttered. One wonders what some of his twentieth-century biographers would then have fallen back on in its absence.

By 1819 Adam’s thoughts had begun to turn towards Vienna, the city of Beethoven, Schubert, Haydn, and Mozart. In those days Vienna was the capital of the musical world. It lay only 50 miles from Raiding, or about three or four hours away by road. Living there was the great piano pedagogue Carl Czerny. Then there was Adam’s old friend Hummel, who had also made his reputation in Vienna. But Hummel was on the point of moving to Weimar, to take up the position of court pianist and Kapellmeister,36 and the prospect of journeying so far seemed unrealistic. Moreover, his fees were high; he charged 1 louis d’or a lesson, an exorbitant sum in those days. Old friendships, apparently, counted for nought.

Several key documents help us to determine Adam’s intentions at this time. The Esterházy archives contain a number of petitions from Adam to his employer, Prince Nicholas Esterházy, asking to be transferred from Raiding to Vienna (where the Esterházys kept a large staff) for the purpose of improving his son’s prospects. These requests were all turned down. Adam was far too valuable an employee to be spared from Raiding. A Vienna posting was a common enough ambition among the provincial stewards scattered across the Esterházy domains, and the prince’s Vienna offices were already overcrowded. Adam then played his trump card. Why should not the prince journey to Raiding and hear the boy for himself? If “Franzi” was indeed talented, the prince might well decide to help by finding Adam an opening in Vienna, thus enabling him to support his family while his son was studying there. The go-between was one Szentgály, a steward; Kapellmeister Fuchs also helped to bring these arrangements to fruition.37 On September 21, 1819, during a hunting party, Prince Esterházy arrived at Raiding and heard the young Liszt play in the presence of Fuchs and others.38 The event was decisive. While the prince could not be prevailed upon to give Adam his cherished Vienna posting, he did promise to contribute financially towards the boy’s education and to grant Adam a year’s leave of absence.39

Adam was disappointed; he had expected more. It appears that Szentgály had even found an opening for Adam as a wine-controller to the Esterházys in Vienna, but Prince Nicholas refused to sanction the transfer.40 Politely, but firmly, Adam in turn rejected the paltry sum of 200 florins Nicholas now sent him in fulfillment of his promise. This action was unprecedented. Since the money had already been drawn from the treasury, Adam’s refusal caused some administrative headaches for the petty bureaucrats in Eisenstadt.41 Thereafter, we detect a note of hurt pride in Adam’s dealings with Nicholas. Family hardships in Vienna would, in the months to come, oblige Adam to beg for more charitable donations from the prince; but it galled him to do so. It was a source of enormous satisfaction to him, in March 1824, to be able to repay Nicholas all this money with interest—a parting shot he would not have dared fire at his boy’s other aristocratic benefactors.42

On April 13, 1820, Adam petitioned the prince yet again, drawing attention to his son’s growing musical powers.

The fact that within twenty-two months he has easily overcome any difficulty in the works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Clementi, Hummel, Cramer, etc., and can play the hardest piano pieces at sight, in strict tempo, correctly and without any mistakes, represents in my opinion giant progress.43

This petition, like the others, was turned down. Starting with this date, Adam became obsessional. The Esterházy documents disclose a father prepared to sacrifice everything for the sake of his talented son. He pointed out that even Eisenstadt, one of the cultural centres of Hungary, was far too limited a place in which to develop his son’s artistry, and he now put forward a bold plan. It took the form of an educational curriculum for his son consisting of three broad aims:

1. to send the child to Vienna, where he would receive a proper moral [sic] upbringing;

2. to provide an excellent music teacher who would work with him at least three times a week; the boy would also learn French and Italian;

3. in order to secure rapid progress the boy would attend as often as possible concerts, operas, and sung masses.44

The total bill, Adam declared, would come to 1,500 florins. The prince’s share would consist only of the educational expenses; living expenses would be taken care of by Adam. This was a desperate compromise borne of Adam’s fear that if a bargain could not be struck with his intransigent employer, he and his family might remain forever prisoners of the mud and sheep of Raiding.

The reason for Adam’s concern is not hard to find. A few months earlier, in the summer of 1819, he had paid a brief visit to Vienna, taking the seven-year-old boy with him, and had called on Carl Czerny. This visit was carefully documented by Czerny himself. It happens to be one of the best descriptions of the young Liszt to come down to us, all the more valuable because of its objectivity. Czerny was one of the shrewdest pedagogues of the day, a keen observer of music and musicians, and a man well qualified to evaluate musical talent.

One morning in the year 1819, a short time after La Belleville45 had left us, a man with a small boy of about eight years approached me with a request to let the youngster play something on the fortepiano. He was a pale, sickly-looking child who, while playing, swayed about on the stool as if drunk, so that I often thought he would fall to the floor. His playing was also quite irregular, untidy, confused, and he had so little idea of fingering that he threw his fingers quite arbitrarily all over the keyboard. But that notwithstanding, I was astonished at the talent which Nature had bestowed on him. He played something which I gave him to sight-read, to be sure, like a pure “natural”; but for that very reason, one saw that Nature herself had formed a pianist. It was just the same when, at his father’s request, I gave him a theme on which to improvise. Without the slightest knowledge of harmony, he still brought a touch of genius to his rendering. The father (his name was Liszt, and he was a minor official in the service of Prince Esterházy) told me that he himself had taught his son up to now; but he asked me whether, if he came back to Vienna a year later, I myself would accept his little “Franzi.” I told him I would be glad to, of course, and gave him at the same time instructions as to the manner in which he should meanwhile continue the boy’s education, in that I showed him scale exercises, etc. About a year later Liszt came back to Vienna with his son and occupied a house in the same street where we lived, and I devoted almost every evening to the boy, since I had little time during the day.46

This document is important for several reasons. Liszt’s first meeting with Czerny is not supposed to have occurred until 1821, after Adam had settled his family in Vienna. But Czerny’s statement indicates that they met two years earlier, long before the “official” lessons began. The romantic story of Adam Liszt arriving in Vienna, beseeching the unyielding Czerny to hear his son play, and having Franz, close to tears, break down Czerny’s resolve with a dazzling display of pyrotechnics is simply—a legend.47 Far from being arranged on impulse, these lessons were planned in advance, and became the raison d’être for the Liszt family’s leaving Hungary. The impending move to Vienna helps to explain why Adam now chose to bring his son to public attention. He needed money, and he was resolved to raise it through concerts and private subscription.

Adam presented his son to the public for the first time at a concert held in the Old Casino,48 in nearby Oedenburg, in October 1820. The concert was arranged by a blind flautist, one Baron von Braun,49 who had himself been an infant prodigy but was now out of favour with the public. Liszt was an “additional attraction,” the baron doubtless hoping that the presence of a wunderkind on his programme would attract a larger audience and revive his sagging fortunes. Liszt played the Concerto in E-flat major by Ries, and he extemporized a fantasy on popular melodies. His success was overwhelming. Adam touchingly related in his diary that just before the boy seated himself at the piano, the fever attacked him once more, “yet he was strengthened by the playing. He had long manifested a desire to play in public and exhibited much ease and courage.”50

Emboldened by this success, Adam announced that the boy would appear in a concert of his own at Pressburg, the ancient capital of Hungary. He shrewdly arranged the concert for Sunday, November 26, so that it coincided with a meeting of the Diet, when the city was full of Hungarian magnates. The concert, which was held at noon, was a glittering occasion, for the audience consisted largely of members of the nobility. Franz appeared in a braided Hungarian costume,51 and was given a tumultuous reception. We still have a press report of the event which appeared in the Pressburger Zeitung.

Last Sunday, on the 26th, at noon, the nine-year-old virtuoso pianist Franz Liszt had the honour of playing the piano before a glittering assembly of local nobility and connoisseurs of music in the home of Count Michael Esterházy. His extraordinary skill and his ability to decipher the most difficult scores and to play at sight everything placed before him was beyond admiration and justifies the highest hopes.52

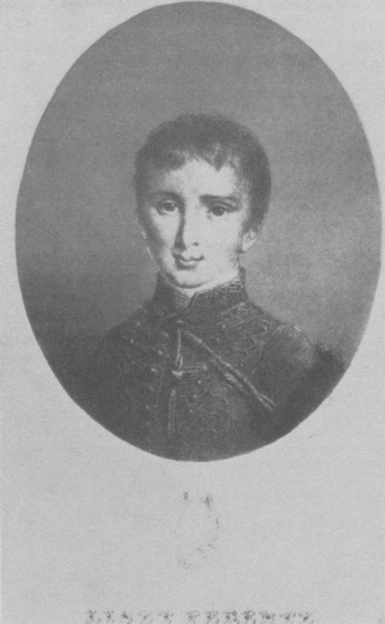

Liszt aged eleven, in Hungarian costume, a lithograph by Ferdinand Lütgendorff (1823). (illustration credit 1.1)

A group of Hungarian noblemen now came forward and offered to establish a fund to enable Liszt to pursue his studies abroad. They were led by Counts Amadé, Szapáry, and Michael Esterházy, and for the next six years they guaranteed Liszt an annual stipend of 600 florins.53

And so the Liszt family prepared to move to Vienna. There were still difficulties ahead. Adam’s finances were in a parlous state, and he had no job. Looking back on those early years, Liszt was astonished that he should ever have survived them. No great composer had ever started from humbler beginnings. Cut off from the civilized world, condemned to lifelong servitude in the tightly run Esterházy domains—it seemed to him in retrospect a miracle that his family succeeded in breaking out of these narrow confines and that he himself leapt to world prominence before he was fifteen years old. For this he thanked his father, to whom he affectionately ascribed an “intuitive obstinacy—a quality found only in exceptional characters.”54 As for Anna, a highly practical housewife, she had looked on anxiously while her husband sacrificed his secure position for the sake of the boy’s career. She is said to have given up her dowry of 1,200 gulden, carefully set aside across the years of their marriage, to help towards her “Franzi’s” education in Vienna, since she believed unshakeably in the calling of her son.55

1. OFL.

2. BNR, p. 222.

3. The Great Comet, one of the most celebrated of modern times, was discovered by Flaugergues at Viviers on March 26, 1811, and last seen by Wisniewski at Neu-Tscherkask, in south Russia, on August 17, 1812—an unprecedented period of visibility. Sir William Herschel studied the comet in detail and made some precise observations about it (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of 1812). The comet left its mark on many different fields of human activity. One of its more unscientific consequences was the wine crop of that year, which happened to be particularly fine. “Comet wine” was much sought after, and featured in merchants’ price lists and auction sales until the 1880s.

4. GL, p. 159.

5. GL, p. 135. See also APL, August 19, 1886.

6. See n. 56 on p. 45.

7. CLV. Father Johannes Stefanits, who baptized Liszt, looked after both parishes from 1796 to 1838.

8. Liszt’s name was neither the Hungarian Ferenc nor the French François. Least of all was it the German Franz, the name by which he is universally known today. He usually signed himself F. Liszt, thereby doing nothing to resolve the confusion. As a child he was known at home by the diminutives Zischy and Franzi (see the correspondence between Adam and Carl Czerny, LCRT).

9. FM, pp. 24–26.

10. OFL, from the diary of Adam Liszt.

11. Ibid. Edward Jenner’s technique of vaccination by grafting had been introduced in 1798.

12. As the child walked onto the platform to make his début at Oedenburg, a fever swept over him (p. 68). Again, during a public concert in Paris in 1835, he collapsed at the keyboard and was carried off the platform “in a fit of hysterics.” (RML, vol. 1, pp. 48–49.) In November 1839 Liszt cancelled a concert in Vienna because of a fever which made his hand “tremble fearfully.” (LLB, vol. 1, p. 32.) It was a fever which prevented him from fulfilling his engagements in Leipzig in 1840, and which Liszt described as “violent shuddering.” (ACLA, vol. 1, p. 414.) Shortly afterwards we find Liszt taking harmful quantities of quinine, while on tour of England, to help fight a chronic feverishness. (ACLA, vol. 2, pp. 29–30.) All his life, those nearest and dearest to him were concerned lest he catch a chill, which always seemed to have more serious consequences for him than for others. ACLA, vols. 1 and 2, is full of such references. Liszt died after contracting a cold, which he neglected, and which culminated in fever and pneumonia.

13. LLBM, p. 110. Liszt was deeply attached to this particular aunt, who used to visit Raiding during his childhood. Her full name was Maria Therese Lager (1790–1856), and in later life she lived in Graz. When she died, Liszt wrote a letter of consolation to his mother: “Dearest Mother, Your dear, good, and excellent sister Therese has passed away! As prepared for this news as one could be, it nevertheless brings a deep mourning to my heart—for you know that I always remember everything good that she rendered me in my childhood, when she rescued me from death, and I remained loyal and deeply devoted to her. If you possess, perhaps, some small object of hers—a book, a cup, or something else of no value, send it to me here, where it will remain dear and precious to me.” (Weimar, January 2, 1857.)

14. LHFL. Johann Rohrer (1783–1868) remained the schoolmaster of Raiding for sixty-one years, from 1805 to 1866, retiring when he was eighty-three years old. This is confirmed by the parish records, Annales Parochiae Lok cum filialibus Lakfalva et Doborján, scriptaeber parachum Joannem Prikosovich, A.D. MCMXVIII. Rohrer’s income was recorded as 66 fl., 97 kr. When Liszt revisited his natal village in 1840 he remembered Rohrer and made over a large gift of money to his old teacher. (Társalkodó [Pest], vol. 3, no. 25, 1840.)

15. RLKM, vol. 1, p. 152.

16. LLB, vol. 6, p. 184.

17. In later life he tried to correct this drawback by taking lessons in Hungarian from a Budapest monk called Zsigmond Vadász, but soon abandoned the effort. (LLM, p. 131.)

18. Acta Mus. nos. 4205, 4209, 3477.

19. Acta Mus. no. 3471.

20. Acta Mus. no. 3500.

21. Acta Mus. no. 3383.

22. In a revealing letter to an unknown correspondent in Eisenstadt, written from Paris some years later (March 20, 1824), Adam asks to be remembered to all his old colleagues and singles out some of them by name. He writes: “Now, dear friend, some news of Eisenstadt. How are Herren Schubernigg, Steffi, Walch, Fajt, Verex, and Kapellmeister Fuchs? What are my good friends the Breusters doing, the fine “Tonerl” Tomasini, etc., the fat Schuster, and all those thousands of artists?” (DM.)

23. OFL, from the diary of Adam Liszt. Since much of our information about Liszt’s earlier years comes from Adam Liszt, and since there is so little of it, we have to proceed cautiously over a difficult stretch of ground. Adam seems to have written his diary at a later date, after his son’s early triumphs in Pressburg and Vienna, by which time he clearly perceived his boy to be a genius. Without going so far as to suggest that his diary was merely written for posterity, we may infer that Adam realized that a “journal” such as this, carefully tracking his son’s progress, would one day prove to be an invaluable basis for biographical articles about his famous child.

Fragments of the diary, which has since disappeared, were first published by Joseph d’Ortigue. In his “Etude biographique” of Liszt (OFL) d’Ortigue publicly thanked Anna Liszt for allowing him access to it. Haraszti, one of the more sceptical of Liszt researchers, insisted that the diary never existed. He claimed that it was nothing more than a random collection of newspaper cuttings pasted into a scrapbook, begun by Liszt’s father and later continued by Marie d’Agoult. (HPL, fn. 24.) This miscellany is now in the Versailles library among Madame d’Agoult’s papers, under the title “Second Scrapbook.” (ASSV.) But the quotations from Adam Liszt used by d’Ortigue and others are not to be found in this “Scrapbook,” thus rendering it a quite different source from the diary. Moreover, Adam Liszt himself mentions his diary as early as 1824. In a revealing letter to Carl Czerny, in which Adam described his son’s sensational successes on his English tour, he wrote, “Ich könnte Ihnen noch Vieles schreiben, allein mein Tagebuch soll Ihnen einstens alles haarklein sagen” (“I could write still more to you, but my diary will one day tell you everything to the last detail”). (LCRT, p. 241.) Lina Ramann made a number of efforts to find Adam’s diary. In the 1870s she sent Liszt a letter asking where it might be located. Liszt replied: “My mother used to possess a few parts of this diary. Since her passing, I don’t know what became of them.” (WA, Kasten 351, no. 1.) Liszt’s answer is further proof that Adam’s diary at one time existed.

24. OFL, the diary.

25. HLP, part 1, fn. 15. HPL, p. 130.

26. Budapesti Bazár, Pesti Hölgy-Divatlap, no. 22, Nov. 15, 1873. Koch (KLV, p. 18), who also reports this anecdote, wrongly calls the Hirschler family “Rehmann.” The Hirschlers, in fact, were rich Jews who later fell upon hard times. By 1865 they had been reduced to selling shoes from an old stall in the Vienna market. Fanni herself married into poverty, but she followed Liszt’s subsequent career with interest.

27. FM, vol. 1, pp. 24–25.

28. ZLEF, vol. 2, p. 102ff. Also SB, p. 58.

29. LLBM, p. 145. Liszt made this comment in 1862. He means Unterfrauenhaid, where he was baptized.

30. Ibid.

31. Liszt’s will, dated September 14, 1860 (LLB, vol. 5, p. 52).

32. On the complex question of the authenticity of Liszt’s books and articles, see pp. 20–23.

33. RGS, vol. 6, pp. 345–46. It can surely be no accident that Liszt’s own art placed such a high premium on improvisation. A regular feature of his recitals during the 1840s were his fantasies on given themes, publicly announced in advance. He was constantly elaborating variations on standard repertory works, even during performance, a practice which appalled Joachim, among others, and which got Liszt a bad name until he abandoned it and took a more rigorous view of the printed text. Liszt could never bear merely to reproduce music. Something new, fresh, and creative had to take place during each act of music making in order to justify that act at all. His love of arranging, paraphrasing, and transcribing springs from the same source.

34. SC, p. 108.

35. LLB, vol. 4, p. 316, August 13, 1856.

36. He held the post from 1819 until his death in 1837. By a curious coincidence, this was the same post that Liszt took up twenty-three years later, in 1842.

37. Johann Nepomuk Fuchs (1766–1839), a Former pupil of Haydn, had been appointed Kapellmeister at Eisenstadt in 1809. The composer of many masses and twenty operas, Fuchs was one of Adam’s most valued musical colleagues and took an active interest in Franzi’s early development.

38. Acta Mus. nos. 170, 4213. See also CLV, p. 633.

39. Acta Mus. no. 3279.

40. Acta Mus. no. 170.

41. Acta Mus. no. 3506.

42. DM, p. 19. Something of Adam’s bitterness towards Prince Nicholas rubbed off onto Liszt himself. In his marginal corrections to Johann Christern’s biography of him (CFLW), he struck out Prince Nicholas’s name, whom Christern had identified as one of his benefactors, and added the terse comment: “Old Prince E. never did anything for me.…” (p. 9) The statement sounds ungrateful, and it is not entirely true. All his father’s frustrations as a humble intendant of the Esterházy sheepfolds come out by proxy, so to speak, on such occasions.

43. April 13, 1820. Acta Mus. no. 3500.

44. Acta Mus. no. 170.

45. Anne de Belleville (1808–80), another infant prodigy who made Czerny’s name known throughout Europe.

46. CEL, pp. 27–28. A document in the Esterházy archives helps us to pinpoint this visit quite accurately. Acta Mus. no. 170 discloses that Adam was given eight to ten days off on August 12, 1819. The primary purpose was to search out employment in Vienna. Since Adam and the boy were back in Raiding by September 21, we may assume that the first encounter between Liszt and Czerny took place in mid-August 1819. This same document, written by Szentgály the steward, also reveals that Adam wanted “to attend his son’s concert in Baden” during this trip to Vienna. There is no mention of this Baden concert in the local press, nor is there any corroborating document in the Baden archives. (See CLV, p. 632.)

47. See RLKM, vol. 1, p. 35, where the story originated.

48. This building, which dominated the Casino Platz in Oedenburg, was burned down in 1834.

49. RLKM, vol. 1, p. 25. He died before he was twenty. Some sources refer to the baron as a violinist.

50. OFL, the diary.

51. See the picture opposite.

52. November 28, 1820. This press notice makes it clear that the concert took place not in the palace of Prince Nicholas, but in the home of a lesser relative.

53. CFLW. Liszt confirms this figure in a marginal note on p. 11 of Christern’s book. He also inserted the name of Michael Esterházy as one of his principal benefactors. On p. 9, as we have seen, he struck out the name of Prince Nicholas Esterházy, and went on, “I should under no condition want this thoroughly wrong information to gain credence.” Even at the end of his life Prince Nicholas was Liszt’s bête noire. He was angered by Trifonoff’s biographical sketch of him (TL), which had repeated the story that Nicholas had given him “loads of presents” as a child. Liszt scratched out the offending sentence and added, “Prince Nicholas never gave me a single present.” (WFLR, p. 216.) The wealth of these Hungarian magnates, incidentally, was beyond calculation. In 1809 the gross returns from the Amadé estates for that year alone were 800,000 florins. (KHC, p. 143.)

54. VFL, p. 111.

55. Acta Mus. no. 3279; GL, p. 135.