When you have the misfortune, as I have, to be both critic and creative artist, you have to put up with an endless succession of Lilliputian trivia of one sort or another, the most nauseating of all being the cringing flattery of those who have or are going to have need of you.

HECTOR BERLIOZ

I really don’t know whether any place contains more pianists than Paris, or whether you can find anywhere more asses and virtuosos.

FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN1

Among Liszt’s intimates during the post-revolution years was Hector Berlioz. The two musicians first met on December 4, 1830.2 The following day Liszt attended the first performance of Berlioz’s Fantastic Symphony at the Paris Conservatoire and was struck with the power and originality of that seminal work. Berlioz at this time was in the midst of his tempestuous love-affair with Marie Moke, the concert pianist, whose infidelities were driving him to the brink of suicide. No sooner was this affair terminated than he picked up the threads of an earlier romance with the Irish actress Harriet Smithson. Berlioz himself has told the story of the comedy of errors that constituted his courtship of Harriet so unforgettably that no later commentator can improve upon it. Liszt, a confidant of Berlioz and privy to his innermost thoughts, felt constrained to utter some reservations about “Henrietta” which Berlioz proceeded to ignore—to his later regret. The ill-fated marriage was solemnized at the British Embassy on October 3, 1833, and Liszt, attempting to repair whatever damage his remarks may have caused Miss Smithson, closed ranks behind his friend and took part in the ceremony as an official witness.3

During the years that followed, Berlioz suffered grinding poverty (Henrietta brought little to the marriage except her debts), and he was forced to undertake hack journalism in order to survive. In January 1834 Paganini commissioned him to write a new work so that he might show off his recently acquired Stradivarius viola. The result—Harold in Italy—did not please the virtuoso (“I am not given enough to do”), and the first performance was given with Urhan as the soloist.4 It was not until the winter of 1838 that Paganini first heard the work that he had inspired. Deeply moved, be declared Berlioz to be the successor to Beethoven. Berlioz has related in his Mémoires how Paganini approached him in the company of his twelve-year-old son, Achille. The violinist was already suffering from the tuberculosis of the larynx which was to kill him two years later, and he could barely whisper. He signalled to Achille, who climbed onto a chair and placed his ear close to his father’s mouth. After listening intently the boy climbed down again and addressed Berlioz: “My father bids me tell you, sir, that never in all his life has he been so affected by any concert. Your music has overwhelmed him.…”5 A few days later Paganini sent a gift of 20,000 francs to the impoverished Berlioz by the hand of Achille in recognition of the composer’s genius. The rumour was later put about by Paganini’s detractors that this gift was really from Armand Bertrand, the wealthy proprietor of the Journal des Débats, who wished to do good by stealth and used Paganini as his cover, but the tale is now discredited.6 (Berlioz’s Mémoires do not lack imaginative touches, but neither do they create deliberate falsehoods.) After Achille had left his bedside (Berlioz had collapsed with influenza immediately after the concert) the astonished composer summoned his wife, and together they knelt down and gave thanks. It is extraordinary to think that Berlioz heard the great violinist who played such an important role in his life on only one occasion, at a chamber-music concert.

In his Mémoires Berlioz invariably speaks of Liszt with warmth and affection. At their first meeting Berlioz introduced Liszt to Goethe’s Faust, a book “which he had not read but which he soon came to love as much as I.”7 As their friendship ripened they came to address one another with the familiar tu (apart from d’Ortigue and later J. W. Davison, the critic of The Times, Liszt was the only nonrelative whom Berlioz allowed himself to address in the intimate form). For twenty years Liszt remained Berlioz’s strongest advocate. After Liszt had settled in Weimar, and attempted to give modern music a new direction, he did not forget his old friend. In 1852, and again in 1855, he arranged week-long Berlioz festivals in the presence of the composer at which such works as Benvenuto Cellini, Lélio, and the Fantastic Symphony were performed. Shortly afterwards their friendship cooled, owing to the mercurial Frenchman’s antipathy towards Wagner, whose cause Liszt also championed at Weimar. Here Berlioz found an unexpected ally in Princess von Sayn-Wittgenstein, Liszt’s mistress during the Weimar years, whose dislike of Wagner surpassed his own and who took over more and more of the correspondence with Berlioz. It was the princess who sustained Berlioz in his efforts to complete his magnum opus The Trojans (the opera is dedicated to her), a work which she regarded as driving the last nail into the coffin of Wagner and music drama.

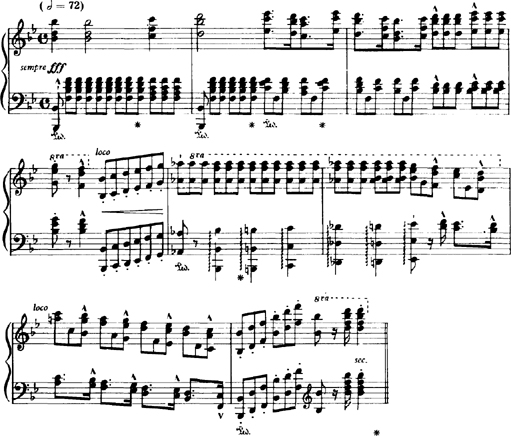

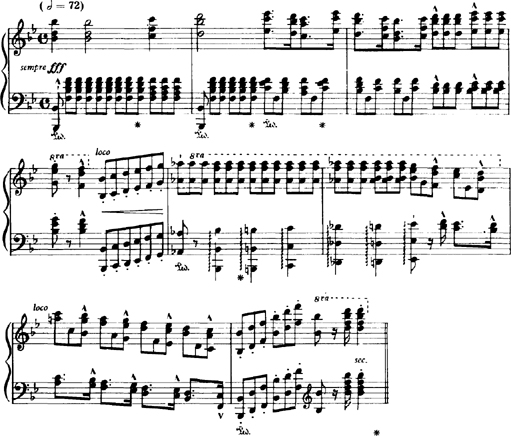

But all this lay in the future. And nowhere did the future shine more brightly than in Paris, on December 5, 1830, when the world first hearkened to the strains of the Fantastic Symphony. Is there more idiosyncratic orchestral music anywhere? Despite the technical difficulties, Liszt contrived to transfer this unique work to the piano and render its complex textures playable by ten fingers. His chief motive was to help the poverty-stricken Berlioz, whose symphony remained unknown and unpublished.8 Liszt bore the expense of printing his keyboard transcription himself, and he played it in public mainly to popularize the original score. Not the least remarkable aspect of this mammoth undertaking was that Liszt was only twenty-one years old when he completed it, in September 1833.9 Sir Charles Hallé heard him play the “March to the Scaffold” in 1836, at a concert in Paris, and wrote:

At an orchestral concert given by him and conducted by Berlioz, the “March to the scaffold” from the latter’s Fantastic Symphony, that most gorgeously instrumented piece, was performed, at the conclusion of which Liszt sat down and played his own arrangement, for the piano alone, of the same movement, with an effect even surpassing that of the full orchestra, and creating an indescribable furor. The feat had been duly announced in the programme beforehand, a proof of his indomitable courage.10

One can well believe that passages such as the following would have rolled across the hall like peals of thunder when drawn from the keyboard by Liszt’s hands.

Schumann’s detailed review of the Fantastic Symphony was written with Liszt’s piano transcription at his side (he was unable to consult the orchestral score).11 It has been remarked that such a feat has few parallels in the annals of criticism. In fact, Schumann’s feat was made possible by an even greater one: the fidelity to Berlioz’s score of Liszt’s transcription, which, at times, approaches the accuracy of a mirror held up to the object it seeks to reflect.

Apart from anything else, Berlioz and Liszt were drawn together by the uncommon breadth of their artistic tastes, which did not stop at music but ranged across poetry, drama, and painting. Another quality they shared was a lifelong dislike of academicism, and their reckless disdain for narrow pedantry brought them early into conflict with the establishment, as punishment for which they suffered the slings and arrows of stupid enemies; but each assault only forced them to become more original. As true children of the July Revolution they were both caught up in the spiritual regeneration of Jeune France, whose cultural horizons now seemed limitless, and the maelstrom of ideas which whirled about Paris in the 1830s swept them both towards that brief flirtation with Saint-Simonism which has already been observed. Shakespeare, Byron, and Beethoven were particular heroes, masters who illuminated the stony path which destiny would oblige both men to tread in the years ahead. To have heard Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto performed by this pair of Dionysian spirits (Berlioz conducted the concerto with Liszt as soloist in Paris in April 1841) must have been an unforgettable experience, an occasion to make one regret that Edison had not yet invented the phonograph.12

Like everyone else, Berlioz had quickly succumbed to Liszt’s piano playing, and particularly to his playing of Beethoven. They were once invited to the home of the critic Ernest Legouvé, together with Eugène Sue and the playwright Prosper Goubaux, and in the course of the evening a typically Romantic scene ensued. The group had moved into Legouvé’s drawing room, which possessed a piano, only to discover that there were no lights and that the fire had burned low. Goubaux brought in a lamp while Liszt seated himself at the piano. “Turn up the wick,” said Legouvé, “we can’t see,” whereupon he accidentally turned it down, plunging the room into almost total darkness. Doubtless prompted by the gloom, Liszt began playing the Adagio of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata while everyone remained rooted to the spot. Occasionally the fire’s dying embers spluttered and cast strange shadows on the wall as the music unfolded its mournful melody. The experience was too much for Berlioz, who could not master his emotions. As Goubaux lit a candle, Liszt pointed to his friend, who had tears streaming down his cheeks, and murmured, “See, he has been listening to this as the ‘heir apparent’ of Beethoven.”13 As it happened, Beethoven’s mantle fell on neither of them, but the fact that the remark was uttered at all indicates the central position that the Viennese master, who had died barely four years earlier, already occupied in their young universe. It must be remembered that Beethoven was still viewed with suspicion by the ordinary music lover. Paris audiences in particular were convinced that his late works were the product of a deranged mind. (When the C-sharp minor Quartet was performed there in the late 1820s, most of the audience walked out.) It was not until the second half of the nineteenth century that a more favourable climate prevailed. Seen in this context, Berlioz’s short study of Beethoven, published in 1829, and Liszt’s public performance of the Hammerklavier Sonata in 1836 were acts of courage matched by few other musicians of the day.

By 1832 Paris had become a city of émigrés. Italians, Poles, and Austrians who had escaped political oppression at home flocked there and formed communities in exile in a society which was now regarded as the most tolerant in Europe. The Polish insurrection of 1831, especially, drove large numbers of refugees from Warsaw to the French capital, including the poet Mickiewicz, the dramatist Słowacki, and Chopin, where they added yet more colour and variety to this cosmopolitan city. Chopin was in the midst of a tour of Austria and Germany when he heard of the fall of Warsaw, and he found himself abruptly cut off from his native land. More by accident than design, he wandered into Paris in the autumn of 1831, in a mood of bitter despair. He was destined to remain there, except for brief intervals, for the rest of his life. Chopin’s fierce patriotism (his exile made him more Polish than the Poles), his intensely nationalistic music, his aristocratic aloofness, and his utterly original approach to the keyboard set him apart from the Paris Virtuoso School, and with the passing years has transformed him into a unique figure. As his frame was slowly ravaged by tuberculosis, all thoughts of a performing career were abandoned. (Chopin played in public fewer than a dozen times in his life; the very rarity of his appearances made them events to cherish.) His contemporaries had at first little idea of the importance and originality of Chopin’s music, and most of them would have found it unbelievable that this frail, pale-faced young man, who stood less than five feet, two inches tall and weighed a mere ninety pounds during his final years, would one day be placed among the musical giants of his age. John Field described him as “a sickroom talent,” and both Rellstab and J. W. Davison (critics for Berlin’s Iris and London’s Times, respectively) did their best to obstruct Chopin’s career by issuing a series of carping criticisms against him over the years.14 As late as 1841 Davison could write that “the entire works of Chopin present a motley surface of ranting hyperbole and excruciating cacophony,”15 a phrase which serves to remind us that musical criticism, then as now, was helpless when confronted by the new and unexpected.

Almost as soon as Chopin entered Paris, Liszt made his acquaintance. He attended Chopin’s début at the Salle Pleyel on February 26, 1832, and he appeared on the same platform as Chopin on April 3 and December 15, 1833. Chopin cemented these early connections by dedicating to Liszt his newly published set of Twelve Studies, op. 10. What Chopin thought of Liszt’s performance of these pieces was expressed in a letter to Ferdinand Hiller the following year.

I am writing without knowing what my pen is scribbling, because at this moment Liszt is playing my studies and putting honest thoughts out of my head. I should like to rob him of the way he plays my studies.16

Although the names of Chopin and Liszt are frequently linked in the popular imagination, the notion of a romantic friendship is a legend fostered by the nineteenth-century biographies. Chopin frankly disliked Liszt’s theatricality, his playing the grand seigneur, and he came to regard Liszt the composer as a mere striver after effects. (Liszt, it should be remembered, had not yet found his true direction and hardly came into his own until after Chopin’s early death.) The question of Chopin’s influence on Liszt has often been debated. Anyone who is even remotely familiar with the general style of both composers knows that they lie far apart and are connected through externals only. For a time, though, Liszt lay under the spell of certain individual compositions of Chopin; in particular, the ghosts of Chopin’s A-flat major Polonaise (op. 53), the F-minor Study (op. 10), and the Berceuse later turned up to haunt some of Liszt’s middle-period works.17 A close inspection of Liszt’s F-minor Transcendental Study reveals some intriguing similarities to Chopin’s own F-minor Study, which Liszt is known to have played. The opening themes of both works appear to have been cast from the same mould.

At such moments as these (and there are dozens from which to choose), the two composers seem to be interchangeable. Yet it is precisely on such occasions that we must exercise the most caution if we wish to avoid becoming ensnared in a historical trap. The F-minor Transcendental Study as we know it today is an outgrowth of the juvenile version that Liszt composed as a youth of fifteen, long before he had heard a note of Chopin. Liszt, in other words, often received more from himself than he received from others. This topic of influence may be a paradise for historians, but it is full of pitfalls for those who do not know their Liszt in toto.

A rift arose between the two composers in early 1835. The apparent cause was Marie Pleyel, the recently estranged wife of Chopin’s friend Camille Pleyel.18 Liszt is said to have used Chopin’s apartments in the rue de la Chaussée d’Antin for a tryst while Chopin was out of Paris, and on his return Chopin felt compromised. While the story is basically unprovable, certain pieces of circumstantial evidence do support it.19 By the late spring of 1835 Liszt had moved to Geneva, and thereafter to Italy, so the two musicians rarely met. Liszt, for his part, never lost interest in Chopin’s music and often included it in his programmes, particularly the polonaises, studies, and mazurkas.20 In his Weimar masterclasses, held during the ’seventies and ’eighties, Liszt constantly encouraged his pupils to play Chopin, and his remarks on this repertoire show that his admiration for it remained undiminished.21 After Chopin’s death in 1849 Liszt conceived the idea of writing a biography of him. He sent a questionnaire to Chopin’s sister Louise in order to acquire some basic information for his book; she regarded Liszt’s approach as tactless, however, and the questionnaire was filled in by Chopin’s pupil Jane Stirling. Liszt’s book, a pioneering study of the Polish master, was eventually written in collaboration with the Princess von Sayn-Wittgenstein and was published in 1852.22

Among Liszt’s other acquaintances in Paris, two call for special mention. The stature of that strange, enigmatic figure Charles-Valentin Alkan23 has undergone a radical transformation in our time. Still not enough is known about his personal relationship with Liszt, but for a brief period in the 1830s the two pianists were friendly. Alkan was the only composer of his time to write transcendental keyboard music to approach that of Liszt. His Douze Etudes dans tous les tons mineurs, op. 39, which includes the four-movement Piano Symphony and the variations called Festin d’Esope, are among the most difficult and original compositions of the century. (How ironical that these modern-sounding pieces are dedicated to the arch-conservative Fétis!) Like everything else Alkan wrote, this music was badly neglected by his contemporaries and remained little known except to a small circle of devotées. In our own century Busoni, Petri, Sorabji, and Isidore Philipp were consistent champions of his compositions, but a correct evaluation of his oeuvre remains one of the more urgent priorities facing musical criticism. The very titles of some of his compositions indicate how utterly different and unconventional they are. The man who wrote Fire in the Neighbouring Village, Funeral March for a Dead Parrot, and the very first musical illustration of the newfangled railway-engine, Chemin de fer, was a pioneer, and the trail he blazed still beckons.

Alkan had been a child prodigy, enrolling in the Paris Conservatoire as a pupil of Zimmerman when he was only six. By the time he was fifteen he had walked off with all the major piano prizes at the Conservatoire, assisted Zimmerman in his piano classes as répétiteur, and stood on the brink of a shining career. Like Liszt, Alkan went the rounds of the Paris salons. At one of these soirées, given by Princess de la Moscova, his natural pleasure at his success turned to humiliation when a tall young man with a grave countenance was invited to the piano and played so brilliantly as to make Alkan feel like a beginner. He tells us that he returned home, wept tears of frustration, and spent a sleepless night. It was his first encounter with Liszt.24 During the 1830s, Alkan moved into the fashionable Square d’Orléans, where Chopin and George Sand became his next-door neighbours, and set up as a teacher. (When Chopin died many of his pupils went over to Alkan; Chopin also left to him the manuscript of his uncompleted piano method.) Liszt, too, was a frequent visitor at this time. Alkan dedicated to Liszt his Trois Morceaux dans le genre pathétique, op. 15,25 and in April 1837 the two pianists appeared on the same concert platform together in Paris. In later life Liszt told Frits Hartvigson that Alkan had the finest technique of any pianist that he knew, and when we inspect some of Alkan’s more problematic keyboard works we must acknowledge that Liszt’s remark may not have been the sort of idle compliment in which he was wont to indulge in his old age.

Alkan’s performing career was blighted by an introverted personality which forced him to withdraw from public life while still relatively young. For his last forty years he lived like a hermit, shut off from the world, and even close friends had difficulty in gaining access to him. The concierge had strict instructions never to let anyone pass. Alkan rented two apartments, one above the other, the better to encapsule himself from the rest of mankind, and it was not unusual for visitors who had somehow penetrated the front line of defence and reached the lower set of rooms to wander around confirming for themselves that they were empty. When Frederick Niecks visited Paris in 1880 he tried to call on Alkan, only to be told by the well-drilled concierge that he was “not at home.” Niecks persisted and asked when he would be at home. The concierge rose to his duties superbly and replied, “Never.”26 The cause of Alkan’s withdrawal into solitude may never be fully known, but it dates from 1848. That was the year he was manoeuvred out of a piano professorship at the Conservatoire by the joint efforts of Auber and Marmontel, after months of bitter wrangling, and although Marmontel’s interesting character-sketch of Alkan in Les Pianistes célèbres, written thirty years later, holds out an olive branch in its closing paragraph, Alkan experienced a lifelong sense of betrayal. His letters to his old friend George Sand, whom he asked to intercede in his behalf, make sad reading. When he died in 1888 he was all but forgotten; only a small handful of admirers remained. Le Ménestrel carried an obituary notice which summed up his unusual fate: “Charles-Valentin Alkan has just died. It was necessary for him to die in order to suspect his existence. ‘Alkan,’ more than one reader will say, ‘who is Alkan?’ ” The cause of his demise was unusual: he was trying to reach for his copy of the Talmud on the top shelf of a bookcase which toppled over and crushed him to death.27

The name of Ferdinand Hiller rarely receives more than passing mention in books about Liszt, yet his path never ceased to cross Liszt’s in an amazing series of coincidences. Pianist, teacher, composer, conductor, and writer, roles in which he industriously attempted to outmatch his contemporary, Hiller even contrived to be born in the year of the comet, 1811, only two days after Liszt. A pupil of Hummel in Weimar (a privilege vainly coveted by the young Liszt), Hiller had arrived in Paris aged sixteen, four years after Liszt, with the same reputation of having been presented to Beethoven. He met Marie d’Agoult long before Liszt himself was introduced to her (Marie and Hiller were both born in Frankfurt-am-Main), and he later followed them to Italy, becoming one of Marie’s closest confidants. Their correspondence suggests that Hiller saw in Liszt not a friend but a rival. Hiller, who conducted the Gewandhaus Concerts in Leipzig in 1843–44, became jealous of Liszt’s direction of the German festivals during the 1850s and launched a series of intrigues against him. At the Aachen Music Festival, which Liszt directed in 1857, Hiller created a disturbance during the rehearsals and had to be ejected. His subsequent criticism of Liszt in the Cologne press was damaging enough to provoke a public rebuke from Liszt’s pupil Hans von Bronsart.28 Even the honorary doctorate bestowed on Hiller by the University of Bonn in 1863 only served to remind him that a similar honour had already been extended to Liszt by the University of Königsberg more than twenty years earlier. Hiller’s Künstlerleben contains an “Open Letter to Franz Liszt” written in 1877, in which he reviews their long connection in flattering detail and dwells on their youth in Paris with particular pride. This document should mislead no one; it is merely a diplomatic smokescreen behind which Hiller continued to work against Liszt to the end.29 The story of their declining relationship happens to be of more than anecdotal interest: it presents a visible example of the fate suffered by so many of the musical relationships Liszt formed during his halcyon days in Paris, a fate which will already have struck the reader with force. One by one his early acquaintances either abandoned him or turned against him—Berlioz, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Hiller, Heine, Schlesinger—and this pattern was later repeated with Schumann, Joachim, von Bülow, and Wagner. In view of the many personal kindnesses extended by Liszt to all these colleagues over the years, their rejection of him is bewildering, and it tinged his life with sadness. When we read today that Liszt was “one of the leaders of the Romantic movement,” the phrase, however true, has a somewhat hollow ring to anyone familiar with the minutiae of his life; the fact is that for much of the time there was no one willing to be led by him at all, and for the last twelve years of his life he resigned himself to artistic isolation. This wholesale refusal by most of the great names of the Romantic movement to take Liszt seriously, let alone recognize his fundamental contribution to their cause, must await its explanation in a later volume of this work. Meanwhile, these musicians were young, their horizons seemed limitless, and their world was full of promise.

1. BM, p. 239; SCC, vol. 2, p. 39.

2. Berlioz wrote to his father on December 6, “Liszt, the well-known pianist, literally dragged me off to have dinner at his house and overwhelmed me with the vigor of his enthusiasm.”

3. Liszt’s reservations about Harriet were as old as marriage itself. See TBC, vol. 1, p. 240, for Berlioz’s response, written four days after the wedding night.

4. November 23, 1834, at the Paris Conservatoire.

5. BM, p. 248.

6. One of the chief culprits was Ferdinand Hiller, who claimed to have received the story from Rossini. (HK, p. 89.) Paganini’s original credit note, drawn on Rothschild’s bank in Paris, is now in the Liceo Musicale Niccolò Paganini in Genoa. It was reproduced by de Courcy (CPG, vol. 2, p. 185) and is proof positive that the account of this episode that Berlioz left in his Mémoires is absolutely correct. It never seems to have occurred to those who want to rob Paganini of this magnanimous gesture that they are virtually accusing Berlioz of forging the letter he claimed to have received from Paganini, telling him of the gift of 20,000 francs, which he published for all the world to see in his Mémoires. (BM, p. 248.)

7. BM, p. 139. It was entirely appropriate that in the years ahead their mutual admiration for Faust would be expressed through reciprocal dedications of works inspired by Goethe’s masterpiece: Berlioz dedicated to Liszt his Damnation of Faust, while Liszt dedicated to Berlioz his Faust Symphony.

8. The score was finally printed in 1845 by Schlesinger.

9. “The Fantastic Symphony will be finished on Sunday evening. Say three ‘Pater’ and three ‘Ave’ on its account.” (ACLA, vol. 1, p. 36.)

10. HLL, p. 38.

11. NZfM, no. 3, 1835, pp. 1–47. Since Liszt cues in the orchestral instruments—a lifelong practice with him in this sort of work—his transcription can also serve the mundane purpose of a conductor’s “piano reduction.” Both Liszt and Berlioz (who checked the proofs of Liszt’s transcription) are caught snoring in the first movement: bar 401 is missing. Schumann’s favourable review was written partly as a retaliation against the hostile one supplied by Fétis for the Revue Musicale, in which that intrepid critic of all things new (Fétis had a nearly unblemished record of going wrong whenever called upon to express an opinion on the modern music of his day) had labelled the symphony “flat and monotonous” and had dismissed its harmony as “bunches of notes simply thrown together.” Even Mendelssohn called the work “a deadly bore.” (Letter to Moscheles, April 1834.) In the controversy that swirled around this composition from its very beginning, Liszt stood out as its first and most consistent champion.

12. Liszt and Berlioz came together again on the platform in the first performance of Liszt’s E-flat major Piano Concerto on February 17, 1855, during the second Berlioz week at Weimar.

13. LSS, vol. 2, pp. 144–45.

14. When he first observed Chopin’s finger-twisting Studies, op. 10, Rellstab sarcastically warned his readers not to play them. “Those who have distorted fingers may put them right by practising these studies; but those who have not should not play them, at least not without having a surgeon at hand.” Rellstab then published a spurious letter, a “reply” to such criticism, purporting to come from Chopin but which may have been forged by Rellstab himself. (Iris, vol. 5, 1834.) Chopin could only look on in bewilderment. Eventually Rellstab realized that his attacks on Chopin were making him look foolish. In 1843 he turned up in Paris bearing a diplomatically worded letter of introduction from Liszt (“however hard it may usually be for artists and critics to agree,” etc., SCC, vol. 3, pp. 128–29), which served to heal the breach. Rellstab may well have been the only music critic in history to go to jail for his views: a criticism of Henrietta Sontag in 1826 in which he satirized a respected diplomat earned him a three-month stretch in Spandau prison.

15. Musical World, October 28, 1841.

16. SCC, vol. 2, p. 93.

17. For a fuller discussion see WL, pp. 58–65.

18. Marie Moke had married Camille Pleyel in 1832, almost immediately after her stormy engagement to Berlioz had been broken off. There was a twenty-five-year difference in their ages, and Marie was persistently unfaithful to her elderly husband. They lived together for barely three years, although Marie continued to use her husband’s name for her professional career as a concert pianist, which spanned the next forty years. Camille Pleyel later repudiated his wife for her conduct and cut her out of his will (1855).

19. ACLA, vol. 1, p. 313. In 1839, four years later, Liszt met La Pleyel again in Vienna and wrote about their chance encounter to Marie d’Agoult: “She asked me if I remembered Chopin’s room.… Of course, madame, how to forget?”

20. ACLA, vol. 2, p. 379.

21. GLK, pp. 48, 75–76.

22. RGS, vol. 1. Liszt’s questionnaire was reproduced in Souvenirs inédits de Frédéric Chopin, recueillis et annotés par Mieczyslaw Karlowicz (Paris, 1904). Louise received it less than three weeks after her brother’s funeral (Liszt’s covering letter is dated “Pilsen, November 14, 1849”), so the timing could hardly have been worse. Also, it contained intimate inquiries about the relationship between Chopin and George Sand which Louise regarded as both irrelevant and impertinent. Jane Stirling fielded Liszt’s questions in such a masterful way that her responses, while true, are virtually useless for biographical purposes.

23. His real name was Charles-Valentin Morhange. Alkan was his father’s first name, a Hebrew word meaning “the Lord has been gracious.”

24. BAEP, p. 136.

25. The individual titles of these pieces are “Aime-moi,” “Le Vent,” and “Morte.” Schumann wrote a blistering review of the work for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (no. 8, 1838) in which he described it as “false, unnatural art,” an early indication of the slow headway this music would make across the century.

26. NPR, pp. 4–7.

27. The ultimate source for this familiar story was Isidore Philipp, who claimed to have been present when Alkan’s body was pulled from under the bookcase. Philipp was one of the four solitary mourners who witnessed Alkan’s interment in the Montmartre Cemetery on April 1, 1888. His description of Alkan’s death has been challenged, but never disproved. (See SA, pp. 73–75.)

28. LLB, vol. 2, pp. 333–34, and vol. 3, p. 91.

29. What was the real cause of Hiller’s jealousy? Marie d’Agoult often unburdened herself to Hiller and disclosed details of her relationship with Liszt that amount to a breach of loyalty. To conclude on the basis of their correspondence (some of which was published in La Revue Bleue, November 1913; see also pp. 261 and 264 of the present work) that there had been a great intimacy between Hiller and Marie d’Agoult is perhaps dangerous, but there was enough gossip about their friendship (which persisted into the 1870s) to make it possible for Olga Janina to work this triangle into one of her satirical novels, Le Roman du pianiste et de la cosaque (ZRPC). Behind the masks of “Nélida” (Marie), “Bernheim” (Hiller), and “François-Xavier” (Liszt), Marie and Hiller are made to cuckold Liszt. Marie lived long enough to read this humiliating parody of her friendship with Hiller; she died the following year. Hiller’s “Open Letter to Franz Liszt” was written a few months later. (HK, pp. 204–12.)