Ramparts of granite, inaccessible mountains now arose between ourselves and the world as if to conceal us in those deep valleys, among the shadowy pines, where the only sound was the murmuring of waterfalls, the distant thunder of unseen precipices.…

MARIE D’AGOULT1

Marie arrived in Basel, in the company of her mother, at the beginning of June 1835 and took rooms at the Drei Könige hotel. She had not yet summoned up the courage to tell her family about her future plans, let alone her present condition. That fact stands revealed in a letter she wrote to Liszt shortly after her arrival in Switzerland.

Wednesday, Drei Könige

Basel, June 5, 1835

Let me know at once the name of your hotel and your room number. Don’t go out. My mother is here; my brother-in-law has left. By the time you read this, I will have told her. Up to now, I haven’t dared say anything.

It is the last, difficult trial, but my love is my faith and I am avid for martyrdom.

Liszt had arrived in Basel after Marie, on June 4, and had registered at a different hotel in order to avoid meeting her relatives. The last sentence of his reply was written in English, presumably to avoid detection.

Since you called for me, I am here.

I shall not go out till I see you—My room is at the Hôtel de la Cigogne number twenty at the first étage—go at the right side.

Yours2

It used to be a commonplace of the Liszt literature that he had gone to Basel for no other purpose than to escape the clutches of Marie d’Agoult, and that she, on finding that her young lover had fled Paris, pursued him to Switzerland, there to throw herself on his charity.3 The facts speak differently. We have a letter from Liszt, written to his mother, in which it becomes abundantly plain that the elopement to Switzerland was planned in Paris, that Basel was merely a temporary solitude, and that Liszt was far from unhappy at the hand fate had dealt him.

Dear Mother,

Beyond all expectations, we arrived in Basel at ten o’clock this morning.… Longinus [one of Liszt’s pet names for Marie] is here, also her mother. I don’t know anything definite yet, but we will probably leave here in four or five days’ time, taking her femme de chambre with us. We are both in fairly good spirits, and have no intention of being unhappy.

I am well, the Swiss air strengthens my appetite.…

Adieu.… I will write to you again soon.4

The Viscountess de Flavigny now learned for the first time of the crisis through which her daughter was passing. The countess returned to Paris alone in order to break the sensational news to the rest of the family. The attitude of Maurice, Marie’s elder brother and head of the family, appears to have been both generous and forgiving. He wrote Marie a letter full of tender and affectionate understanding, and thoughtfully enclosed a little note from Marie’s daughter, Claire, then five years old: “I embrace you. Will you come back soon?”5 Marie had expected reproaches. Had her family’s attitude been harsh and uncompromising, it would have been easier to bear. But this letter from Maurice, who had not been trained as a diplomat for nothing, nearly broke her heart.

The lovers tarried at Basel for a week. It was during this trying time that they decided on Geneva as their ultimate refuge. This French-speaking city was a quiet backwater, far enough away from Paris for the couple to feel reasonably insulated against the scandal their elopement would provoke. Moreover, Liszt had useful connections there; he had made at least two previous visits to the city in earlier years. Thanks to the good offices of the parents of his pupil Pierre-Etienne Wolff, who now lived there, Liszt was able to rent an apartment in the city at 1, rue Tabazan. On June 14 the couple set out for Geneva, making several excursions into the Swiss countryside along the way. They arrived at Lake Constance on the 16th. A few days later they were at Lake Wallenstadt, which Liszt immortalized with his piano piece of that name. Marie d’Agoult later wrote in her Mémoires, “The shores of Lake Wallenstadt detained us for a long time. Franz wrote for me there a melancholy harmony, imitative of the sigh of the waves and the cadence of oars, which I have never been able to hear without weeping.”6 By the 23rd they had made the ascension of St.-Gothard. Following the Rhône Valley, they were at Martigny by July 1. After sojourning at Bex for a few days, they continued their journey, finally arriving in Geneva on July 19.

The house on the rue Tabazan in which the lovers installed themselves still stands today. It occupied the corner site next to the rue des Belles-Filles.7 Liszt wrote to his mother, describing it as “a magnificent residence,” and asked her to send from Paris his manuscripts, his library of books, his piano, and other personal possessions.8 Although he and Marie lived there for only thirteen months, it was clear that they at first regarded it as a permanent home. News of the distinguished couple’s arrival spread swiftly. They were pleased to receive some unexpected visitors from Paris—Prince Belgiojoso, Countess Potocka, Mallefille, and Ronchaud. Among the habitués of the rue Tabazon were the doctor Coindet, the botanist Pyrame de Candolle, the politician James Fazy, the orientalist Alphonse Denis, and the economist Simonde de Sismondi. One of the best accounts of Liszt’s first few weeks in Geneva comes from the journal of Madame Auguste Boissier, then living in Geneva. Ever since their lessons in Paris in 1832, Valérie Boissier had showered Liszt with invitations to visit her family in Switzerland.9 Little could she have imagined the circumstances of the reunion when it finally took place. It was in their imposing house (called Le Rivage) that the twenty-three-year-old Liszt presented his runaway countess, “without blushing,” and apparently shrugging his shoulders “at the blessing of marriage and similar bagatelles,” to the honest burghers of this straitlaced, Calvinist community.10

Marie idealizes this “honeymoon period” in her Mémoires. For her, the rue Tabazan seemed at first a paradise, a perfect setting for the realization of a cherished dream. Here, in this isolated retreat, she would become Liszt’s Egeria, his inspirational guide. And through the stream of masterpieces that would now pour from his pen, her “great man” would be revealed to the world—together with the true nature of her sacrifice. Not for a humdrum piano player had she callously abandoned hearth and home, but for a shining genius whose matchless art would one day vindicate her choice. Meanwhile, the world had to be helped. It is no accident that on June 14, just two weeks after their elopement to Switzerland, the Gazette Musicale came out with Liszt’s first “official” biography, by Joseph d’Ortigue. The timing was perfect; the word “genius” appears frequently. On May 3, that same journal had published the first part of Liszt’s literary effort “On the Position of Artists”; and the following December the Gazette carried his first Bachelor of Music essay, “To George Sand.” Whether written by Liszt or by Marie, or more likely by them both, these articles served to burnish Liszt’s image and present him to the public as a philosopher and a seer.11

Marie’s horizons could not remain cloudless for long. Her elation was diminished by the sudden arrival in Geneva that August of Liszt’s fifteen-year-old pupil Hermann Cohen.12 This gifted youth, having been Liszt’s student in Paris for the past two years, was now inseparable from him. “Puzzi” had become a familiar sight in the Faubourg districts, accompanying Liszt to his concerts. George Sand had already immortalized his name in one of her Lettres d’un voyageur, in which she gives a memorable depiction of the boy standing by his master’s side, turning the pages.13 Puzzi had started pining for Liszt almost as soon as his teacher had left France, and Liszt now gave him permission to come to Geneva. Cohen arrived in the company of his elder brother and their mother. Madame Cohen had been obliged to place her young daughter in a Paris boarding school and undertake the journey to Switzerland at a financial loss, and the family took up residence near Liszt so that Puzzi might resume his daily lessons. It was entirely characteristic of the fatherly attitude Liszt adopted towards his pupils that he thought it quite normal to see them every day, and even have them move into his home and live with him en famille;14 and it was equally characteristic of Marie d’Agoult that she should object. In her Mémoires she makes heavy weather of Hermann’s abrupt appearance in Geneva. She was piqued that Liszt had not properly discussed the matter with her before bringing an “intruder” into the house. “Six days later,” she wrote, “a resounding hammer blow fell on the outside door of the house. Somebody ran up the stairs, four at a time, brushed past the servant, and threw himself around Franz’s neck. It was Hermann.”15 Puzzi stayed in Switzerland for almost a year. His name appeared in the Geneva concert programmes several times during the 1835–36 season, and we shall find him adding some unexpected colour to Liszt’s life during this period.16

The event for which Liszt and Madame d’Agoult had eloped to Geneva duly presented itself. Their first child, Blandine-Rachel, was born there on December 18, 1835. The birth certificate, filed at the Geneva registry office three days after the delivery, contains some interesting details.

On Friday, December 18, 1835, at 10:00 p.m. was born in Geneva, 8, Grande Rue, Blandine-Rachel Liszt, the natural daughter of François Liszt, professor of music, aged twenty-four years and one month, born at Raiding in Hungary, and of Catherine-Adélaïde Méran, a lady of property, aged twenty-four years, born at Paris, neither parent being married and both domiciled in Geneva. Liszt has freely acknowledged that he is the father of the child and has made the declaration in the presence of Pierre-Etienne Wolff, professor of music, aged twenty-five years, and Jean James Fazy, proprietor, aged thirty-six years, both domiciled in Geneva.

Witnessed in Geneva, this 21st day of December 1835, at 2:00 p.m. [Signed]

GOLAY, civil servant

F. LISZT

J. J. FAZY

P. E. WOLFF17

The three witnesses signed this document without turning a hair, but they all knew that they had perjured themselves by bearing false testimony. Catherine-Adélaïde Méran was none other than Countess Marie d’Agoult, married; she was not twenty-four but thirty years old; and she was born at Frankfurt-am-Main, not Paris. Moreover, she did not live at 8, Grande Rue. The civil servant Golay knew two of the witnesses very well. James Fazy was the celebrated publisher of the Journal de Genève; it is amusing to see the future mayor of Geneva putting his hand to this document. Pierre Wolff was a respected professor at the newly opened Geneva Conservatoire. Many years later Marie d’Agoult herself explained why this document was fabricated. It was not possible to disclose her identity, she said, without making Blandine the legitimate child of Count Charles d’Agoult. “Liszt and I had but one thought: to avoid this monstrosity.”18

Blandine was handed over to a local wet-nurse, Mlle Churdet. A few months later, when Liszt and Marie left Geneva, the child was left behind with a certain Pastor Demelleyer and his family until Marie could send for her. This arrangement, made with good intentions, was to lead to many complications later on.

Liszt’s arrival in Geneva coincided with an important musical event: the founding of the Geneva Conservatoire of Music. For years the city had needed an institution of higher musical learning; its best talent usually defected to Paris or Brussels. Thanks to the efforts of a newly formed board of directors, and encouraged by the generous patronage of François Bartholoni, its first president, Geneva’s Conservatoire opened its doors in the autumn of 1835. The institution offered courses in solfège, piano, singing, violin and cello, and wind instruments. At first the piano students were split into two groups. Madame Henri was appointed to teach the ladies, Pierre-Etienne Wolff the gentlemen.19 The unexpected arrival of Liszt in Geneva threw these plans into disarray. Liszt offered his services to Bartholini, proposing to give lessons to the advanced students “on condition that the course be free.” He further offered to prepare for the Conservatoire a “piano method.” Such an opportunity could not be lost. Unfortunately, Madame Henri did not relish the thought of working with a celebrity, and she resigned her appointment. A further complication arose when the Conservatoire admitted no fewer than thirty-three piano students—twenty-eight ladies and five gentlemen—at the start of the first term. Liszt was asked to take on ten students; Wolff was given thirteen. Liszt suggested that the remaining ten be taught free of charge by his young pupil Hermann Cohen, “for whose talents and morals he would be answerable.”20 The board of directors accepted the offer, but decided that Hermann should be remunerated in the same way as Pierre Wolff.

We still have Liszt’s “class book” in which he notated various comments on the progress of his students.21

| Julie Raffard | Remarkable musical feeling. Very small hands. Brilliant execution. | |

| Marie Demelleyer22 | Vicious technique (if technique there be), extreme zeal but little talent. Grimaces and contortions. Glory to God in the Highest and Peace to All Men of Good Will. | |

| Ida Milliquet | An artist from Geneva. Languid and mediocre. Fingers good enough. Posture at the piano good enough. Enough ‘enoughs,’ the grand total of which is not much. | |

| Jenny Gambini | Beautiful eyes. |

By January 1836 Wolff had left Geneva for Russia. Liszt therefore proposed that Wolff’s position be offered to Alkan (nothing came of this interesting idea); in the meantime, he and young Hermann would take on Wolff’s pupils as well as their own. The directors turned down this proposal; Liszt’s multifarious interests, they thought, would not allow him to do justice to so many students.23 Liszt himself then left the Conservatoire, in the summer of 1836. Bartholini presented him with a gold watch and chain as a token of their esteem. As a further mark of recognition, Liszt was given the title “Honorary Professor of the Geneva Conservatoire.”

And what of the “piano method” which Liszt had promised to prepare? It is mentioned several times in the Minutes of the Directorate meetings. On July 13, 1836, for instance, Bartholoni was recorded as saying, “Liszt has confirmed his intention of offering the rights of his method to the Conservatoire, on condition that the latter pay the costs of engraving and printing.” A few months later, on October 12, Bartholoni informed his colleagues that “Liszt himself has decided to carry out the engraving at his own expense. He has requested permission to dedicate his oeuvre to the Geneva Conservatoire and to offer it some copies.” These copies never arrived. Nothing more is known of Liszt’s “method,” which appears never to have existed.24

It was while he was living in the rue Tabazan that Liszt brought to fruition some of the pieces in his Album d’un voyageur, which later found their way into the “Swiss” volume of that great three-part collection of works he called Années de pèlerinage.25 Liszt’s life was ever reflected in his art. These pieces, distinctly impressionistic in character, are filled with the sights and sounds of the Swiss countryside, whose natural beauty enchanted him. Earth and air, rain and storm are all represented here. Distant churchbells, cascading falls, mountain echoes, and the cries of Swiss yodellers are among the charming repertoire of effects Liszt incorporates into these soundscapes.

The titles of the “Swiss” volume are:

Chapelle de Guillaume Tell

Au Lac de Wallenstadt

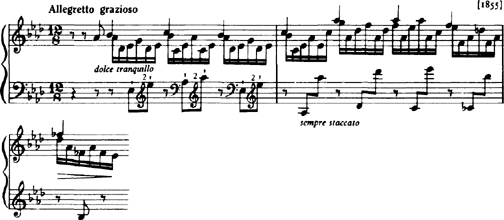

Pastorale

Au Bord d’une source

Orage

Vallée d’Obermann

Eglogue

Le Mal du pays

Les Cloches de G …

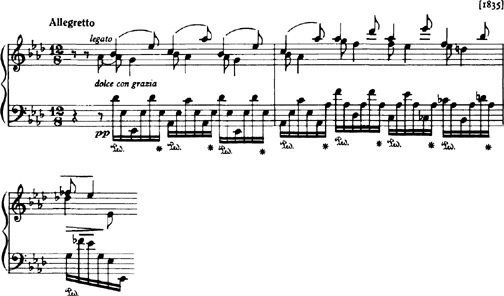

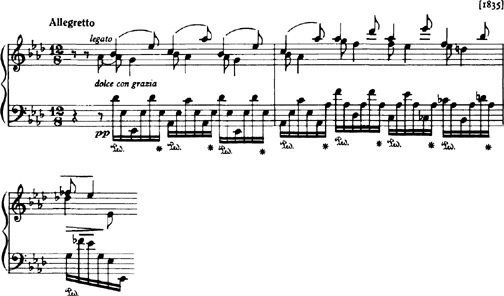

One of the more forward-looking items is Au Bord d’une source, a piece of “water music” prophetic of Ravel’s Jeux d’eau in its evocation of splashing fountains. It is prefaced with a quotation from Schiller: “In murmuring coolness the play of young nature begins.”

The nearly twenty years which elapsed between the first and second versions of Au Bord d’une source saw great changes in Liszt’s handling of keyboard texture. He took immense strides forward during that period, and by the time the piece had reached its definitive form, in 1855, he had discovered a way of unfolding the same music by means of crossing hands, in a much less cumbersome way.

Perhaps the most topical piece in the collection, an evocative testimonial to Liszt’s stay in Geneva, is Les Cloches de G …, which the composer dedicated to his daughter Blandine in commemoration of her birth in that city. It bears a quotation from Byron’s Childe Harold:

I live not in myself, but I become

Portion of that around me.

The opening page attempts to capture distant churchbells drifting across the Swiss valleys. At one point we hear a bell strike ten, perhaps in symbolic depiction of the hour of Blandine’s birth. As the piece gathers momentum, Liszt skilfully combines his bell effects with the main theme of the work, and actually draws attention to them with the word cloche.

When Les Cloches de Genève was drastically revised in the 1850s, Liszt abandoned these programmatic aids along with much of the original musical material. Indeed, the earlier version is so radically different from its “revision” that it ought to be regarded as a separate work and brought back into the repertory.

In a revelatory letter to Ferdinand Hiller, written from Geneva in November 1835, Liszt disclosed his creative intentions thus.

The game I am playing now will take three years to win or lose. Afterwards I will begin again with another; and then yet another, because, thank God, I am only twenty-four years old—the same as you. Three long-winded works, which I hope to have finished by the spring of 1837, and which will be published at that time, will vindicate me, I hope, in the eyes of you other unyielding people.

As for the title, for better or worse, for now:

24 Grandes Etudes

Marie, Poem in six melodies for piano

Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, complete (that is, five or six new items).

What has become of Chopin? Tell me about him, because frankly, I don’t believe I will ever receive two lines from him. Embrace him for me. Also tell him, in order to amuse him, that yesterday evening I played his Etude in E-flat major [opus 10, no. 11] and one of the most eminent artists in Geneva noticed a great analogy with the romance of La Folle! I could tell you a thousand such tales!26

What was the three-year “game” that Liszt declared himself to be playing? Nothing less than total dominion over the piano and a repertoire to embody that fact. As early as 1835, it seems, the twenty-four-year-old Liszt was working on two major piano compositions normally attributed to a later period: the Transcendental Studies (first called Grandes Etudes) and the ten-part collection of pieces called Harmonies poétiques et religieuses. Both collections were to point the piano in a new direction.27

As the summer of 1836 approached, Liszt and Marie planned to explore the Swiss valley of Chamonix, which was dotted with picturesque hamlets and villages and dominated at its southwesterly end by Mont Blanc and its glaciers. They invited George Sand to accompany them. At that moment Sand was detained at La Châtre, a chief witness in the divorce proceedings she had brought against her husband, Casimir Dudevant. The case was a seamy one (involving assault, lesbianism, and the division of property, as well as good old-fashioned adultery) and it dragged on for three months. Judgement was finally given in her favour at the end of July,28 and possession of her family home at Nohant was restored to her control. It was in a mood of elation that Sand, at the end of August, set out for Geneva to meet her old friends.

By the time Sand and her retinue arrived in Geneva (she had brought along her two children, Maurice and Solange, as well as Ursule Josse, her maid), Liszt and Marie d’Agoult had already set out for Chamonix. Liszt had left a note for her at the Geneva hotel where they were all supposed to rendezvous, explaining that their good friend Major Adolphe Pictet would act as her travelling companion. The major (so called because of his pioneering work on percussion shells for the Swiss federal army) sported a fierce beard and a military cape. He reminded Sand of Mephistopheles dressed as a customs official. He was a voracious debater, and within five minutes he and Sand were in the middle of a heated argument about the merits of Swiss democracy. Sand won this particular round by handing the major one of her famous “poetic cigars” (obtained from an obscure source in the Middle East, and wrapped in datura leaves), which left him feeling dizzy.

Posterity owes a debt of gratitude to Pictet and to Sand for leaving such vivid accounts of the Chamonix episode. Pictet’s Une Course à Chamonix and Sand’s tenth Lettre d’un voyageur make mandatory reading for the events which followed.

Arrived in Chamonix, Sand and the major tracked down Liszt and Marie at the Hôtel de l’Union. As Sand looked through the hotel register she saw that Liszt had signed himself in with a series of extravagant flourishes.

| Parnassus | Place of birth: | |||

| Profession: | Musician-Philosopher | |||

| Coming from: | Doubt | |||

| Journeying towards: | Truth |

Sand, rising to the occasion, picked up her pen, and wrote:

| Names of travellers: | Piffoël family | |||

| Domicile: | Nature | |||

| Coming from: | God | |||

| Journeying towards: | Heaven | |||

| Place of birth: | Europe | |||

| Occupation: | Loafers | |||

| Date of passport: | Eternity | |||

| Issued by: | Public opinion |

The hotel lobby was full of staid Englishmen with prim wives who gave Sand’s party some glacial looks. At first the hotel proprietor mistook Sand for a page-boy and the military Pictet for a policeman. “Have you come to arrest them, sir?” the proprietor anxiously inquired. “Arrest whom?” “That band of Gypsies upstairs with long hair and smocks.” From this point the Chamonix episode degenerated into low comedy. It was by now dark. Sand and her exhausted party were led upstairs by a nervous maid holding a flickering candle. They stopped outside room number 13. The maid opened the door, but in the dim light Sand tripped over Puzzi Cohen, who was resting on the floor in a sleeping-bag. Pandemonium broke out. Marie d’Agoult was seized by the “page,” who in turn was seized by the long-haired Liszt in a three-way embrace. The maid, who could not grasp this confusing picture, dropped her candle and rushed downstairs to tell the kitchen staff that the hotel had been overrun by Gypsies. Major Pictet joined them shortly afterwards and found Marie at one end of the sofa clasping a bottle of perfume, her sole defence against Sand, who was sitting at the other puffing clouds of smoke from her long Turkish pipe. Liszt was sitting on the floor between them. The atmosphere seemed sufficiently informal to encourage the major to embark on one of those long philosophical discussions of his (he had journeyed to Berlin to study philosophy with Hegel, and was now not only immersed in the work of Schelling but insisted on immersing everyone else in it as well), and he took as his text “The Absolute Is Identical with Itself.” After a few minutes of this Sand picked up her candle and retired to her room. The argument was interrupted by the sound of violent swearing from the street below. Liszt opened a window to find out what was going on. Three Englishmen were gesticulating angrily upwards. Sand had absent-mindedly aimed a large jug of water at her window box, missed, and drenched the three Britons instead. Liszt went downstairs to placate them, and they finally dispersed when Sand peered over her flower box and apologized for her error.

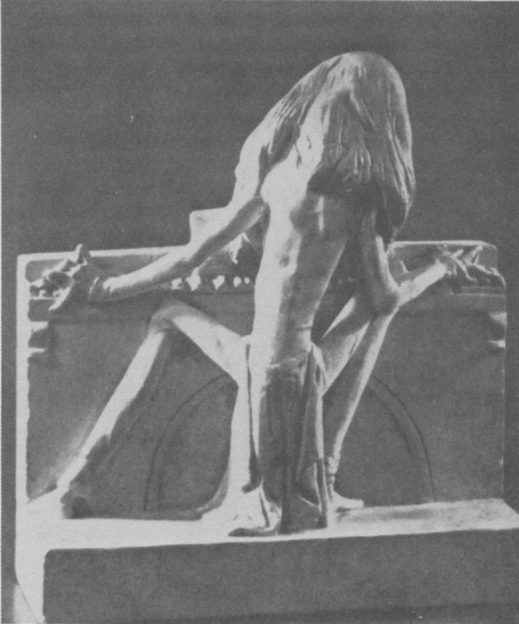

The following evening the motley group created a mild sensation as they entered the crowded dining room. They were shown to a table in a far corner and found themselves sitting opposite a fat Englishman who stared at them in disbelief. “Who are these fellows?” the Englishman kept asking. A Frenchman nearby told him that the man in military uniform (Pictet) was fluent in Sanskrit, that the pale young fellow (Liszt) could play any instrument, and that the young boy with the dark hair (Sand) was a juggler. The Englishman, his curiosity thoroughly aroused, peered at them through his pince-nez. George Sand retaliated by focusing her lorgnette on him and peering back. “My God, he’s ugly,” she exclaimed, forcing the Englishman to look hastily the other way. It so amused Liszt to be referred to as “that fellow,” he adopted the term as a pseudonym. He and Marie were called “Mr. and Mrs. Fellows” for the rest of their stay at Chamonix. At this point the major handed out various nicknames of his own derived from Sanskrit literature. George became “Kamporoupi,” who could change her sex at will; Liszt became “Madhousvara,” the melodious one; and Marie was known as “Arabella,” the thoughtful one.29 In high good humour, the party now retired to their rooms. Liszt had ordered a bowl of hot punch and it was brought in flaming. George Sand handed out more of her “poetic cigars,” which almost certainly contained opium. What happened next was observed by Marie d’Agoult, who, as the only non-smoker in the company, did not succumb to euphoria. When last observed, Liszt was conducting the chairs with a candle snuffer, angrily silencing those who were singing out of tune; Pictet had launched himself into a deep philosophical debate with an imaginary audience somewhere in the ceiling; and George Sand was dancing about the room in fits of laughter. Sand later produced a caricature. “Arabella,” Liszt, and the major are sitting on a sofa. Hanging over them like a black cloud is the notorious caption: “The Absolute Is Identical with Itself.” Liszt, his hair standing on end, asks, “What exactly does that mean?” Pictet admits: “It’s a bit vague.” Arabella, her head buried in the cushions, sighs, “I’ve been lost for ages.”30

Liszt, Marie d’Agoult, and Major Pictet, a caricature by George Sand (1836). (illustration credit 11.1)

The travelling circus now took to the road. There was Liszt, his long hair streaming in the wind, and at his side the major, wearing his military cloak, arguing and gesticulating. Then came Sand in her male attire, smoking a cigar, and Arabella, mounted demurely on a donkey. Gambolling at their heels were Solange and Maurice Sand, and Puzzi Cohen, with his long hair dressed in imitation of his revered master, making him look like a young girl; the maid Ursule brought up the rear. They looked like a strolling band of vagabonds. It is not difficult to imagine the astonishment they aroused at some of the small mountain inns. One of the first stops was Martigny. It was very late when they arrived at the local hotel, and a disgruntled maid let the bedraggled party in. Ursule, who had never been out of France, was sobbing uncontrollably, thinking that the party had arrived at Martinique by mistake. Exhausted, they fell into their beds, only to be awakened by the sound of the major giving Puzzi (with whom he had been obliged to share a room) a good thrashing to stop him from snoring. At Lucerne, “Arabella” and “Kamporoupi” contracted food poisoning, with its attendant consequences. To crown everything, it rained solidly for the rest of the trip.

The most memorable excursion was to Fribourg, where Liszt wanted to see the newly installed Mooser organ in the Church of St. Nicholas. This huge instrument had been fitted out with sixty-three stops and four thousand pipes. As they entered the church an organist was demonstrating its capabilities, simulating, in Sand’s words, “a complete storm, rain, wind, hail, faraway cries, dogs in distress, and thunderbolts.” “It was not what I had expected,” Marie remarked, registering her disappointment. Liszt seated himself at the organ and began an extended improvisation on the Dies Irae from Mozart’s Requiem. As the music rang throughout the church, the full magnificence of the instrument stood revealed. Both Pictet and Sand later wrote of it as an apocalyptic vision, and Sand could not rid herself of the sombre, funereal words of the text:

Quantus tremor est futurus,

Quando judex est venturus.

Suddenly the organ gave up the ghost between Liszt’s hands. The vesper bell had begun to ring. Mozart himself, wrote Sand, could not have persuaded the organ blower to postpone the ritual of his office. “I felt like beating him.…”31

The party spent their last few days in Geneva before finally dispersing. The lights burned into the small hours at the rue Tabazan. Liszt used to play the piano in those convivial surroundings with George Sand sitting underneath the instrument, the only place, she claimed, where she felt “enveloped” by the sound. Inspired by Liszt’s performance of his newly completed rondo El Contrabandista, Sand stayed up the whole of one night and, in a furious burst of creative energy, wrote her short story “Le Contrabandier”—an amplification of Liszt’s rondo. On September 26 they all attended a concert given by young Hermann Cohen in the Casino, at which Liszt and some of his pupils at the Geneva Conservatoire assisted.32 Then, with embraces and kisses all round, and with promises to meet again in Paris, Sand and her group returned to France. The Chamonix holiday was ended.

Liszt and Marie stayed on in Geneva for only two or three weeks. It is clear that they felt they had no permanent future in that provincial capital. They missed Paris and badly wanted to return, but they were uncertain as to the kind of reception that might await them. Barely sixteen months had elapsed since their sensational elopement, and the scandal still smouldered. Marie’s family, in particular, had to be spared further embarrassment. In May 1836 Liszt had made a brief return to Paris in order to meet Marie’s brother, Maurice. Liszt gave an account of this interview in a letter to Marie.33 He made it clear to Maurice that his intentions towards Marie and their child were entirely honourable. Maurice had appeared to be mollified; the professional diplomat in him told him to accept reality. While he thought that Liszt lacked the means to support Marie, he was forced to acknowledge: “Liszt is a man of honour.”34 When the Countess de Flavigny had written to him the previous summer to tell him of Marie’s conduct, Maurice had come back with a remarkably objective letter, full of sympathy for the plight of the runaway couple.

Dear Mother,

All the sad details that you give me on Marie’s misguidedness have profoundly touched my heart and proved to me more and more clearly that no human agency could have saved her. We can only hope that God and the course of time will bring her back. There is absolutely nothing to be done with Marie at the moment, and only in two or three months’ time will you be able to show her how far your maternal devotion goes.…

As for Liszt, you can be completely at rest. I feel very certain that no vengeance or violence on my part would improve the situation at present. I even believe that he is not altogether to blame: he says that he asked Abbé Lamennais to help him. It is true that he did so only after having pretty well set the house on fire, but I feel that we should make allowances for his being only twenty-two years old; only the future can prove what there really is in this man and what consideration he may merit.…35

At this same time Liszt had discreetly sounded out old friends and acquaintances and was relieved to learn that he and Marie would not be unwelcome in Paris. He had also talked frankly to his mother about their situation, and had written back to Marie, “My mother accepts everything.”36

The pair arrived in Paris on October 1637 and installed themselves in the fashionable Hôtel de France at 23, rue Lafitte. Everything went better than they had dared hope. Lamennais came to see them; so did Rossini and Meyerbeer. Hard on their heels followed Berlioz and Chopin. Soon the couple were surrounded by a host of old companions. Among the brilliant men of letters who called on them to pay their compliments were Sainte-Beuve, Balzac, Heinrich Heine, and Victor Hugo. Marie gave a number of soirées and it must have seemed as if she and Liszt were about to be rehabilitated in the eyes of Parisian society. The bevy of artists which surrounded Marie was totally different from the one that she had entertained during her days as a society hostess in the Faubourg St.-Germain. In the Hôtel de France she mixed as an equal with some of the greatest poets, musicians, and novelists of the time. Quick to seize the advantage, she now started to forge that powerful network of connections which would one day be so valuable to her when she turned herself into “Daniel Stern.” Marie wrote enthusiastically to George Sand, now back in Nohant, about her latest circle of literati and invited her to join them. Sand arrived at the Hôtel de France at the end of October and occupied rooms on the floor immediately below Liszt and Marie. They shared a common sitting room where they entertained mutual friends. “Those of mine you don’t like,” wrote Sand, “will be received on the landing.” It was in the Hôtel de France that George Sand was introduced to Chopin and heard him play for the first time. Chopin appears at first to have been affronted by her cigars, her mannish dress, and her flamboyant manners. “What an antipathetic woman that Sand is!” he exclaimed to Hiller as they walked home after the party. “Is it really a woman? I am ready to doubt it.” And to his family in Warsaw he wrote that there was “something about her that repels me.”38 From such unlikely seeds blossomed a grande passion which perplexed even their closest friends, so mismatched a pair did they seem to be. Shortly afterwards (probably in early November) Liszt and Marie took Sand to see Chopin in his apartments in the rue de la Chaussée d’Antin. After some behind-the-scenes prodding, Chopin invited Sand back to his apartments on December 13, when he gave a large soirée. The company included the pianist Pixis, the tenor Adolphe Nourrit, and a number of Polish exiles, led by Albert Grzymala, who had been wounded by the Russians in the winter campaign of 1812. Sand was determined to make a better impression this time and turned up wearing white pantaloons and a scarlet sash—the colours of the Polish flag. Marie d’Agoult served tea and helped pass round ices; Nourrit sang some Schubert songs, with Liszt accompanying. The highlight of the evening was a performance by Chopin and Liszt of Moscheles’s Sonata in E-flat major for four hands, with Chopin playing the secondo part and Liszt the primo. The Sand-Chopin affair, so important in the annals of Romantic music, was aided and abetted in its beginnings by Marie d’Agoult, who was doubtless glad to shift the spotlight from herself and give Paris a different scandal to gossip about.

Liszt gave very few public concerts in Paris during the winter of 1836–37. On December 18 he played at a Berlioz concert and performed his Fantasy on Berlioz’s Lélio. In January and February 1837 he appeared in a series of chamber-music concerts with Urhan and the cellist Batta, featuring the piano trios of Beethoven, which were then totally unknown in Paris.39 At the concert on February 4 an innocent hoax was perpetrated on the unsuspecting Paris public. In order to make a better effect the programme was turned around, the Beethoven trio changing places with a trio by Pixis. No announcement was made. The audience applauded vigorously after the Pixis trio, thinking it to be by Beethoven; the Beethoven trio drew a lukewarm response, everybody assuming it to be by Pixis. Not a word of all this can be found in the contemporary press. The critics of the day, apparently, could not hear the difference.40 (A notable exception was Berlioz, who spotted the switch at once.) The episode merely served to strengthen Liszt’s resolve to insist on “peer criticism,” the right of every artist to be criticized by his equals, and it does not surprise us to find him developing this central theme in his writings.

The ceaseless commotion at the Hôtel de France, and the perpetual discussions among the intellectuals who congregated there about politics, society, Saint-Simonism, and all the other issues then agitating the left-wing liberals of Paris, led the locals to dub the group “the Humanitarians.” It was a good label, and it stuck. A contemporary periodical41 has left a satirical description of one of their gatherings under the title “An Evening with the Gods.”

“Coachman, rue Lafitte, number …” You pay him 32 sous, you knock, then you go up to the porter’s lodge.

“Porter, is Providence at home?”

“Third floor on the mezzanine, the door on the right.”

You climb fifty-seven steps and ring at the gate of Paradise. The bell rope is an old belt which might formerly have been suitable for a lady-in-waiting.

It isn’t Saint Peter who opens the door. Every religion has its retainer. At the Humanitarian Divinity’s establishment it’s a maid who opens Heaven’s gate; she’s a redhead from Picardy.

For we’re at the Humanitarians’. You introduce yourself as an Apostle, you hand in your references from two or three saints, and you are admitted. The Goddess [Marie d’Agoult], who is blonde and cultivated, greets you charmingly.

The Goddess is dressed in Spanish style, with a lace veil on her head, open-work stockings, and pink shoes. She offers you a cigarette. You light up and watch.

All the Gods are gathered together, all the prophets are present. Four old Gods are playing a hand of whist in a corner. Don’t pay any attention to these Ancients.

Behold instead the young Gods; they show great promise, and there are several about whom one can say: Theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.

Some of the other Gods are bursting with wit and talent and could have been very distinguished men if they had not been summoned to the eternal spheres.

Here’s one who deigns to be famous in our corrupt society; he’s fat and well fed; he’s a strong melodious Divinity [Adolphe Nourrit]. Another God moves towards him. What a contrast! This second God is as thin as a rake: it’s the God Franz; he’s indignant.

“O Sublime Intelligence,” someone says to him, “what is troubling you? Is it, by chance, Dantan’s sacrilegious caricature? Should we strike the blasphemous one with lightning?”42

“No,” replies Franz, “I’m too great a God and too great a Pianist not to be above that. Besides, plaster makes one popular. But my thinness has been insulted in quite another way.”

“What’s that, my God?”

“Listen! Just now, I walked on the boulevard past the Jockey Club. Four dandies converged on me and offered me magnificent emoluments if I would be willing to become a racing jockey. As they scrutinized me through their lorgnettes, they said, ‘That fellow doesn’t weigh anything!’ ”

Liszt at the piano, a statuette by Dantan (1836). (illustration credit 11.2)

“What a humiliation!”

“What does it matter to me how much I weigh? What annoys me is that these people don’t recognize me, so there are still some people to whom I am unknown and when I pass by them not everybody says admiringly: It is He!…”

“Oh, the futility of celebrity!”

“Suppose we have some music.”

“Puzzi [Cohen], open the piano!”

At that command the God Puzzi springs up, passes over the heads of three Goddesses, and opens the piano. The God Franz seats himself; his mass of hair flows down to the parquet floor; he parts the curtain of his tresses to reveal his face.

Inspiration comes, the God’s eyes light up, his hair quivers, he clenches his fingers and strikes the keys fervently; he plays with his hands, his elbows, his chin, his nose. Every part that can hit, hits. Finally, to end the piece with a dazzling effect, Franz soars up and falls back to earth with his seat on the keyboard.

“It’s sublime!” they exclaim.

“That will cost me 20 francs in repairs,” says the Goddess of the house.

The God Puzzi says nothing, but swoons away.

“Franz, Thou art Thou!” says a deep-throated voice.

“Thank you,” replies the God, “thank you, George.”

The God thus named [Sand] is dressed in Turkish costume. As a turban he has a floss-silk shawl; he wears bombazine trousers and Turkish slippers of hardened leather. He is smoking cheap tobacco in a clay pipe.

The Turkish God’s posture is completely oriental; the puffs of smoke he blows out create a divine cloud around him; he’s at the centre of conversation. Some people say, “Hello, George!” and others “How are you, madame?”

“Well, Major” [Pictet], the God George says to another God, “how do you think I look in this outfit?”

“You look like a camel-dealer.”

“That lovely major, always so frank, so natural: but what are you doing rumpling my trousers?”

“Don’t pay any attention, I’m seeking the meaning of life.”

“That’s the spirit!” George replies … “but I’m thirsty.”

“Arabella, have them pour me a glass of the blood of the grape.”

Then a little weasel-faced God, spruced up and hopping about, whom they call Monsieur l’Abbé [Lamennais], unfurls a piece of paper; they form a ring around him. “It’s a speech against the Pope,” they say. “You’ll see how the abbé has dealt with him.”

The abbé reads; they applaud; midnight strikes; it’s time to retire. The Gods don’t like to stay up too late. They have chatted, played cards, made music, smoked, drunk, read; it has been a delightful evening. Franz sits down at the piano again and plays the popular song “Allez-vous-en, gens de la noce!” You take your hat and withdraw from Olympus, swearing that they’ll never get you back there again.…

These “evenings with the Gods” were terminated only when the “Gods” themselves dispersed. George Sand left for Nohant in January 1837 and persuaded Marie d’Agoult and Liszt to join her there. Marie arrived in February; Liszt, however, lingered at the Hôtel de France for a few more weeks, finally setting out for Nohant in April. The reason for this delay is not hard to find. A new star had recently arisen in the firmament of pianists: Sigismond Thalberg, whose famous “duel” with Liszt was about to be fought out in the full glare of the Paris arena. This colourful episode, possibly without parallel in Liszt’s early career, is of such absorbing interest that it has been allotted a chapter to itself.

1. AM, p. 42.

2. ACLA, vol. 1, p. 136.

3. The story was put about by Göllerich, among others. (GL, pp. 89–90.) It achieved total fantasy in Schrader: “Liszt, warned by Berlioz, maintained an attitude of reserve towards her; but when he seemed in danger of succumbing, his friends advised him to leave Paris and so avoid a scandal. Liszt, therefore, went in the spring of 1835 to Switzerland. One day when he was sitting at his writing table in Berne [sic] the door flew open and the countess burst in, followed by her servants, who deposited her numerous trunks in the room.” (SFL [2], pp. 29–30.) William Wallace (WW, p. 130) went further, calmly asserting that Marie used the weapon of divorce to bring Liszt to heel, then, “having obtained her decree was after him with tons of portmanteaux and hat boxes.” Marie and Charles d’Agoult were never divorced. On the question of who followed whom to Switzerland, Liszt’s unpublished Pocket Diary proves that he arrived there after Marie. (EDW.) So much for the “chase” theory.

Two other troublesome errors can be disposed of here. Ramann wrongly reported the location of the tryst as Berne instead of Basel. Ernest Newman, in his one-man crusade against Liszt (NML, pp. 51–53), huffs and puffs his way across three pages in an attempt to show that the substitution of Berne for Basel was symptomatic of a plot by Liszt’s official biographer (with Liszt’s own connivance) to cast a smokescreen over his elopement with Marie d’Agoult. Such zeal is worse than useless, since it becomes necessary for later biographers to clear up the mistakes it generates in its wake. In Liszt’s personal copy of Ramann’s biography (WA, Kasten 352, no. 1) the composer himself struck out Berne wherever it occurs and substituted Basel. Ramann’s innocent blunder is one more proof that the first time Liszt ever saw his official biography was when a printed copy was handed to him. The other error stems from the same source. “She was without revenue,” wrote Ramann (RLKM, vol. 1, p. 333), the implication quite clearly being that the countess arrived in Basel penniless and that the twenty-three-year-old Liszt was henceforth expected to shoulder a heavy financial burden, keeping his titled mistress in the luxurious style to which she was accustomed, in addition to coping with all his other cares. This is a romantic notion, designed to make him look chivalrous, but Liszt corrected his copy of Ramann’s book and wrote in the margin the terse comment “nicht richtig” (“not true”). He was the first to acknowledge that during their early years together the countess, who was in receipt of a regular income from her share of the Bethmann fortune, bore most of their expenses.

4. LLBM, pp. 16–17. The original copy of this letter was not dated. We know it to be June 4, however, from collateral evidence in Liszt’s unpublished Pocket Diary. (EDW.)

5. AM, p. 49.

6. AM, p. 45. A detailed itinerary of the excursion from Basel to Geneva can be found in Madame d’Agoult’s “Unpublished Notebooks” (AC).

7. Today the house bears the address 22, rue Etienne-Dumont, and carries a memorial plaque to Liszt, unveiled in 1891.

8. LLBM, pp. 20–22.

9. See Liszt’s letters to Valérie Boissier. Eight of these rare items were preserved by the Boissier family and published for the first time in 1928. (BDLL.)

10. BRRS, pp. 29–30.

11. Liszt was already working on four articles for the Gazette Musicale by November 1835. (LLBM, p. 24.)

12. According to Marie d’Agoult’s “Unpublished Notebooks,” Hermann arrived in Geneva on August 14, less than a month after she and Liszt got there. (AC, folio 63.)

13. SLV, p. 45.

14. Liszt referred to his Paris pupils of this period as “my children.” See his letters to his mother, LLBM, pp. 24 and 27. Later, during his Weimar years, pupils such as von Bülow and Tausig had the run of his home in the Altenburg—the latter living under Liszt’s roof for months at a time.

15. AM, pp. 57–58. Young Hermann was certainly a boisterous youth. Countess Dash dreaded his coming to 61, rue de Provence, for his lessons with Liszt. She describes him as “a rowdy little boy, dressed in overalls, running about the stairways and in the courtyard.” (DMA, vol. 4, p. 149.)

16. Puzzi’s subsequent career may be briefly summarized here. After returning to Paris he fell in with bad company and lost huge amounts of money at the gambling tables. Liszt took him in hand, and in 1841 entrusted him with some private business affairs. Puzzi repaid Liszt by swindling him out of 3,000 francs. (ACLA, vol. 2, p. 183.) He later defended himself by saying that “a plot, prepared with the most diabolical cunning,” had succeeded in estranging him from Liszt, but his explanation (SLFH, p. 32) does not ring true. After drinking the cup of worldly pleasures to its dregs, the dissipated young man was converted from the Judaism of his forefathers to Christianity. In 1850 he became a Barefoot Carmelite priest and was henceforth known as Father Hermann. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 he ministered to the prisoners in Spandau jail, where he caught typhoid fever. He died in Spandau on January 20, 1871, aged fifty. (See E. von Asow’s “Hermann Cohen: Ein Lieblingsschüler Franz Liszts,” Oesterreichische Musikzeitschrift, no. 9, September 1961.)

17. Register of Births, vol. 38, no. 651, State Archives, Geneva.

18. Unpublished letter to Dr. Guépin (Archives Daniel Ollivier), VCA, vol. 1, pp. 393–94.

19. BRRS, pp. 44–51. See the Minutes of the Directorate of the Conservatoire, August 5, 1835, Geneva Conservatoire Library. See also Henri Bochet, Le Conservatoire de Musique de Genève, 1835–1935 (Geneva, 1935), pp. 17–22.

20. Minutes of the Directorate, November 4, 1835.

21. Geneva Conservatoire Library.

22. We surmise that this pupil was the daughter of Pastor Demelleyer, Blandine’s foster parent.

23. Minutes of the Directorate, March 16, 1836.

24. Despite all the rumours to the contrary which have dogged the Liszt literature for years, one of which even has Olga Janina running off with the still-unpublished manuscript of Liszt’s “method” to America in the 1870s and losing it there, we can now say with certainty that it was never written. We have Liszt’s own word for that. When the story of the missing method reached Lina Ramann’s ears nearly forty years later, she asked Liszt point-blank for information about it. His reply was unequivocal: “I have never written such a work, and will never think of writing one.… The only methodisches opus I have committed to writing is a series of technical studies.” (Unpublished letter dated August 30, 1874, WA, Kasten 326.) This refers to the twelve volumes of Technical Studies, a product of Liszt’s maturity published by Alexander Winterberger in 1887 (WTS), a quite different work from that intended for the Geneva Conservatoire in 1836.

25. Liszt’s first title, Album d’un voyageur, was possibly derived from George Sand’s Lettres d’un voyageur, which she had begun in 1835. The “Swiss” volume was originally divided into three parts, called Impressions et poésies, Fleurs mélodiques des Alpes, and Paraphrase. For the genesis of these early pieces, and for their transformation and condensation into the Années de pèlerinage: “Suisse” a decade or so later, see SML, pp. 23–29.

26. UB, p. 45.

27. See the chapter “Liszt and the Keyboard,” where works from both collections are discussed.

28. The details were reported in the July 30–31 issues of Le Droit.

29. Liszt had a lifelong fondness for nicknames. In his correspondence he often refers to Marie d’Agoult as “Longinus” or “Zio.” She in turn dubbed him “Crétin,” a mock tribute to his sharp intelligence. Their three children came to be affectionately known by them both as “les Mouches” (the flies), because as infants they crawled all over one. Hermann Cohen, as we have seen, was known to everyone as “Puzzi,” a houseboy. During the Weimar period Liszt invented a whole battery of nicknames for his pupils, including “Ludwig II” for Anton Rubinstein, who had a striking facial resemblance to Beethoven. The reader who works his way diligently through Liszt’s correspondence will soon conclude that he requires a veritable Who’s Who to keep him on the right track.

30. PCC, p. 144.

31. SLV, p. 309; PCC, pp. 102–3.

32. Le Fédéral printed an appreciative review of Hermann’s playing in its issue of September 30, and drew attention to the presence of Sand in the audience. See KLG, p. 325, where the programme is reproduced in full.

33. ACLA, vol. 1, pp. 159 and 172.

34. WA, Kasten 327.

35. AMA, p. 79.

36. ACLA, vol. 1, p. 163.

37. Not in December 1836, as wrongly reported by Daniel Ollivier (ACLA, vol. 1, p. 180). For the true sequence of events consult Vier (VCA, vol. 1, p. 233).

38. SCC, vol. 2, p. 208.

39. All these concerts took place in the Salle Erard on January 28 and February 4, 11, and 18, respectively. They attracted widespread attention. Berlioz devoted no fewer than three articles to them, published in the Gazette Musicale on February 5 and 19 and March 12, 1837.

40. ACLA, vol. 1, p. 187. The event was later incorporated into Liszt’s Bachelor of Music essay “To George Sand.” (RGS, vol. 2, pp. 139–40; CPR, pp. 118–19.)

41. Vert Vert, December 15, 1836.

42. Dantan’s famous statuettes, depicting Liszt in agonized caricature at the keyboard with a proliferation of fingers at the ends of his hands, had appeared earlier that year (1836). Charivari had actually carried a picture of one on July 11, 1836, shortly before this particular “evening with the Gods.” It was well known that Liszt disliked these statuettes, which, paradoxically, have always been admired by everybody else. Léon Escudier casts an interesting sidelight on Liszt’s reaction to Dantan’s work in his Souvenirs. When Liszt saw the first caricature in Dantan’s studio he complained that the sculptor had exaggerated the length of his hair. After he had left, Dantan started work on a second statuette in which one sees nothing but a head of hair (Liszt is viewed from behind, still seated at the keyboard). That is what one gets, punned Escudier, for “splitting hairs” with a man whose wit extended to the point of his chisel. (ES, p. 341.)