Liszt knows no rules, no form, no dogma; he creates everything for himself.

M. G. SAPHIR1

The years 1839–47 are still described by Liszt scholars as his “years of transcendental execution,” when he embarked on a virtuoso career unmatched in the history of performance. Liszt’s recitals have never been properly chronicled. He visited, among other countries, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Austria, France, England, Poland, Rumania, Turkey, and Russia. Since he often gave three or four concerts a week,2 it is safe to assume that he appeared in public well over a thousand times during this brief, eight-year period. His legendary fame as a pianist, which he continued to enjoy long after his official retirement from the concert platform, aged thirty-five, rested mainly on his accomplishments during these fleeting years. That is a remarkable fact, and before unfolding a detailed account of Liszt’s concert tours the biographer has a duty to stand back and take stock of his achievements. Merely to list them is to observe musical history in the making.

Liszt’s career remains the model which is still followed by pianists today. The modern piano recital was invented by Liszt. He was the first to play entire programmes from memory. He was the first to play the whole keyboard repertory (as it then existed), from Bach to Chopin. He was the first consistently to place the piano at right angles to the platform, its open lid reflecting the sound across the auditorium.3 He was the first to tour Europe from the Pyrenees to the Urals, and that at a time when the only way to traverse such distances was by post-chaise, a slow and often uncomfortable mode of travel. The very term “recital” was his; he introduced it in London on June 9, 1840, for a concert in the Hanover Square Rooms. In Milan and St. Petersburg he played before audiences of three thousand people or more, the first time a solo pianist had appeared before such vast assemblies. His Berlin recitals of 1841–42 are worth special mention: in ten weeks he gave twenty-one concerts and played eighty works—fifty of them from memory.4 Few pianists today could match that feat. It was not merely that he could learn so much, but that he could learn so quickly. One example can stand for the others. When he was in Vienna in December 1839 he was asked to play Beethoven’s C-minor Concerto, which he did not at that time know. Less than twenty-four hours later he played it in public, with an improvised cadenza.5

The pianos which greeted Liszt as he arrived at the smaller provincial towns of Europe give us pause for thought. Liszt played on Broadwoods, Streichers, Pleyels, and Erards—still the last word in piano manufacture. For his tour of Spain and Portugal in 1844–45 Liszt played on a Boisselot which travelled around the country with him, but that was exceptional; he usually played on whatever instrument each town and hamlet could best provide. The results were occasionally unsatisfactory. In Ireland, at the little market town of Clonmel, Liszt played on a small Tompkinson upright which rattled and shook as he performed. Most of those instruments had a restricted compass and a delicate tone best suited to the salon; their light materials made them inadequate for Liszt’s bigger works. Some of the older models which confronted him were little better than boxes of wood and wire, and they sometimes collapsed beneath the strain. Perhaps his worst experience occurred in 1840 at Ems, where he gave a command performance before the Tsarina Alexandra of Russia and her retinue. The piano was old, and as Liszt played the strings started to snap one after another. Bound by strict court etiquette, everyone sat stiff and erect, watching in consternation as the disaster unfolded before them. The instrument might have literally broken to pieces under Liszt’s powerful playing had not the empress finally thought of a way out of the ghastly predicament into which she had plunged her circle, by declaring herself to be ready for a cup of tea. Clara Schumann once described Liszt as “a smasher of pianos.” It is a false image. Even Clara snapped a string or two in public. Most pianists in the first half of the nineteenth century regarded it as a normal hazard of their profession. Liszt’s practical solution was occasionally to have two pianos standing on the platform simultaneously, and he would make a point of moving from one keyboard to the other several times in the course of a recital.6 Not until the great firms of Steinway and Bechstein produced their powerfully reinforced instruments in the 1860s did Liszt’s repertoire of the 1840s come into its own. Necessity was the mother of invention.

No artist before Liszt, not even Paganini, succeeded so completely in breaking down the barriers that traditionally separated performing artists from those who were then grandly called their “social superiors.” After Liszt, all performers began to enjoy a higher status in society. Haydn and Mozart had been treated like servants; whenever they visited the homes of nobility they had entered by the back door. Beethoven, by dint of his unique genius and his uncompromising nature, had forced the Viennese aristocracy at least to regard him as their equal. But it was left to Liszt to foster the view that an artist is a superior being, because divinely gifted, and that the rest of mankind, of whatever social class, owed him respect and even homage. This view of the artist who walks with God and brings fire down from heaven with which to kindle the hearts of mankind became so deeply entrenched in the Romantic consciousness that today we regard it as a cliché. Nonetheless, the cliché is important, since it explains much about Liszt that would otherwise remain a mystery. When he walked on stage wearing his medals and his Hungarian sword of honour, it was not out of vanity but rather to raise the status of musicians everywhere. It was the most telling gesture he could make to show the world that the times had changed. Here, he seemed to say, was an artist with as many titles and medals as a monarch. It would be tedious to list all those titles, but four can be mentioned here. He received the Cross of the Lion of Belgium. The title Cavalier of the Order of Carlos III was bestowed on him by Queen Isabel of Spain, who had the order’s cross encrusted with diamonds. The Sultan of Turkey, Abdul-Medjid Khan, also decorated him in diamonds with the Order of Nichan-Iftikar. Finally, Wilhelm Friedrich IV of Prussia elevated him to the Ordre pour le Mérite, a purely military distinction normally gained on the field of battle. Inevitably it was said of these decorations that Liszt had manoeuvred to get them. The French newspapers, as usual, were the most vocal in their condemnation and fabricated some strange stories. One of their best efforts deserves to be better known. In 1845 they circulated a false report that Liszt was planning to marry the Queen of Spain and that the queen had given him the title of the Duke of Pianozares.7 How could anyone take such a report, to say nothing of such a title, seriously? The general public did, however, since Liszt received a number of letters of congratulation.

If we wish to know what Liszt himself thought about the propriety of public recognition for services rendered towards art, the evidence lies to hand. In 1840 the Gazette Musicale claimed that Liszt had been angling for the Legion of Honour. Liszt at once wrote a strong denial to the editor, Maurice Schlesinger.

London, May 14, 1840

Sir,

Allow me to protest against an inexact assertion in your last number but one:

“Messieurs Liszt and Cramer have asked for the Legion of Honour,” etc. I do not know if M. Cramer (who has just been nominated) has asked for the cross.

In any case I think that you, like everyone else, will approve of a nomination so perfectly legitimate.

As to myself, if it be true that my name has figured in the list of candidates, this can only have occurred entirely without my knowledge.

It has always seemed to me that distinctions of this sort could only be accepted, but never “asked for.”

I am, sir, etc.,

F. LISZT8

That Liszt would have felt contempt for any artist who requested a formal distinction is beyond question. He himself occasionally went out of his way to make an enemy of powerful aristocrats if he thought that his dignity as an artist had suffered. Into this category falls his chilling reply to Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, who arrived late and then started talking during one of Liszt’s recitals in St. Petersburg. He stopped playing and sat at the keyboard with bowed head. When Nicholas inquired the cause of the hushed silence, Liszt replied, “Music herself should be silent when Nicholas speaks.” This public rebuke may well have cost Liszt a medal. It was, as Sacheverell Sitwell pointed out, the first time that “music herself” had answered back. Tsar Nicholas later made it known that he wanted Liszt to give a benefit concert for the survivors of the Battle of Borodino. It was a tactless idea and Liszt refused. “I owe my education and my celebrity to France,” he said. “It is impossible for me to make common cause with her adversaries.” When the tsar heard that, he remarked to one of the ladies of the court, “The hair and political opinions of this man displease me.” This was promptly reported to Liszt, who retorted, “I let my hair grow in Paris and shall cut it only in Paris. As for my political views, I have none and will have none until the day the tsar deigns to put at my disposal three hundred thousand bayonets.”9 A similar scene took place in the drawing room of Princess Metternich in Vienna. After keeping Liszt waiting while she chatted idly with her other guests, she suddenly turned to the pianist and said, “You gave concerts in Italy—did you do good business?” Liszt bowed stiffly and replied cuttingly, “Princess, I make music, not business,” and left.10 Thanks to Liszt, artists soon became the new aristocracy, and the great public was quick to recognize it.

After 1842 “Lisztomania” swept Europe, and the reception accorded the pianist can only be described as hysterical. Admirers swarmed all over him, and ladies fought over his silk handkerchiefs and velvet gloves, which they then ripped to pieces as souvenirs. Sober-minded musicians like Chopin, Schumann, and Mendelssohn were appalled by such vulgar displays of hero-worship and gradually came to despise Liszt because of them. Was Liszt to blame for the unrestrained conduct of his audiences? That is rather like asking whether Niagara Falls is to blame for so many suicides. Liszt was a natural phenomenon, and people were swept away by him. The emotionally charged atmosphere of his recitals made them more like séances than serious musical events. With his mesmeric personality and long mane of flowing hair, he created a striking stage-presence. And there were many witnesses to testify that his playing did indeed raise the mood of the audience to a level of mystical ecstasy. In 1840 Hans Christian Andersen, a close observer of men and manners, happened to be present at one of Liszt’s Hamburg recitals. He recorded his impressions in his travel book A Poet’s Bazaar.

As Liszt sat before the piano, the first impression of his personality was derived from the appearance of strong passions in his wan face, so that he seemed to me a demon nailed fast to the instrument whence the tones streamed forth—they came from his blood, from his thoughts; he was a demon who would liberate his soul from thraldom; he was on the rack, his blood flowed and his nerves trembled; but as he continued to play, so the demon vanished. I saw that pale face assume a nobler and brighter expression: the divine soul shone from his eyes, from every feature; he became as beauteous as only spirit and enthusiasm can make their worshippers.

Not only artists but hardened critics were shaken by Liszt’s magnetic playing. The Russian critic Yuri Arnold once heard Liszt play in St. Petersburg. “I was completely undone by the sense of the supernatural, the mysterious, the incredible,” Arnold wrote. “As soon as I reached home, I pulled off my coat, flung myself on the sofa, and wept the bitterest, sweetest tears.”11

In former times the old aristocracy had had a motto: Noblesse oblige! The new aristocracy, the men of genius, Liszt resolved, should have a motto too: Génie oblige!12 Much of the fortune Liszt accumulated during these years of travel he gave away to charity and humanitarian causes. His work in behalf of the Beethoven monument and his support of the Hungarian National School of Music are well documented. Less well known are his generous gifts towards the building fund of Cologne Cathedral, the establishment of a Gymnasium at Dortmund, and the construction of the Leopold Church in Pest. There were also many private donations to hospitals, children’s schools, and charitable organizations such as the Leipzig Musicians Pension Fund.13 When he heard of the Great Fire of Hamburg, which raged for three weeks during May 1842 and devastated much of the city, Liszt at once gave concerts in aid of the thousands of homeless.14 Never before had an artist given so liberally of his time and his talent. Inevitably his goodness was sometimes abused. He became the target of petty vindictiveness when he was unable or unwilling to help. In Halle he was sued by a local music teacher who claimed that Liszt owed him 4 louis d’or for advance publicity. Liszt fought and won the case. He then felt sorry for the man’s wife, who was in childbed, and sent her 8 louis d’or.15

History has not always been kind to Liszt when reviewing his Glanzzeit. Whatever the final verdict, one thing seems sure. He will never be freed of the charge of not doing more to raise the level of public taste, through his enormous prestige, instead of pandering to its base desires for pyrotechnics and an endless stream of such trifles as his operatic paraphrases, “reminiscences,” and popular arrangements. The low quality of his programme-building is a matter of record. What are we to make of the following, a recital he gave at Kiev in 1847?

| Hexaméron Variations | LISZT |

| Concertstück | WEBER |

| “The Trout” | SCHUBERT-LISZT |

| A Study | CHOPIN |

| Invitation to the Dance | WEBER |

It is eccentric by modern standards. Yet to accuse Liszt of poor taste shows a lack of historical imagination. In 1847 he had nothing to guide him. Indeed, he felt it quite proper to let others plan his programmes for him. “I seldom … planned them myself, but gave them now into this one’s hands, and now into that one’s, to choose what they liked. That was a mistake, as I later discovered and deeply regretted.”16 By leaving the organization of his concerts to others, Liszt sometimes fell victim to amusing errors. He once played in Marseille and included in the programme his arrangement of Schubert’s “La Truite” (“The Trout”). Owing to a printing error the piece appeared as “La Trinité,” and the unsuspecting audience sat through this bubbling music with quasi-religious reverence. When Liszt realized the mistake he got up from the piano and made an impromptu speech, asking the audience not to confuse the mysterious idea of the Trinity with Schubert’s trout, a helpful interjection which caused great hilarity.17

Génie oblige! Liszt’s motto still exacts a posthumous penalty. It was very easy for a later generation of pianists to avoid his mistakes while criticizing him for having made them. By 1860, in fact, long after Liszt had retired from the concert platform, a legend in his lifetime, scores of long-haired, champagne-sodden virtuosos (often with a mere half-dozen pieces in their briefcases) were roving around Europe, vainly trying to emulate his triumphs. Even the greatest pianists of the second half of the nineteenth century—men of the calibre of Tausig and von Bülow, both pupils of Liszt who, at their best, may have equalled him—did not come close to matching his public impact. The reason was simply that Liszt was there first. History does not enshrine the names of those who follow the pioneers.

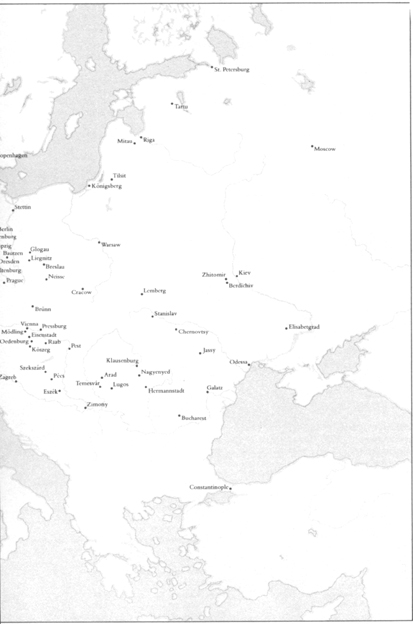

Liszt’s Years of Travel (1838–47: A Summary) (illustration credit 15.1)

Liszt’s fame as a performer rested mainly on the great tours of Europe and Asia Minor undertaken by him during the years 1838–47. His marathon journeys, which spanned thousands of miles, ranged from Lisbon in the west to Constantinople in the east, from Gibraltar in the south to St. Petersburg in the north. The map shows only the main towns and cities in which Liszt played during this remarkably brief period. The list that follows adds more details of his itinerant life. Naturally, he often visited certain places more than once. And in some cities (for example, in London, Berlin, and Vienna) he appeared before the public many times.

Whatever else the world may debate about his life and work, one thing is generally conceded: Liszt was the first modern pianist. The technical “breakthrough” he achieved during the 1830s and ’40s was without precedent in the history of the piano. All subsequent schools were branches of his tree. Rubinstein, Busoni, Paderewski, Godowsky, and Rachmaninoff—all those pianists who together formed what historians later dubbed “the golden age of piano playing”—would be unthinkable without Liszt. It was not that they copied his style of playing; that was inimitable. Nor did they enjoy close personal contact with him; not one of them was his pupil. Liszt’s influence went deeper than that. It had to do with his unique ability to solve technical problems. Liszt is to piano playing what Euclid is to geometry. Pianists turn to his music in order to discover the natural laws governing the keyboard. It is impossible for a modern pianist to keep Liszt out of his playing—out of his biceps, his forearms, his fingers—even though he may not know that Liszt is there, since modern piano playing spells Liszt. When he was already thirty years old, Busoni began the study of the piano afresh in order to remedy what he considered to be defects in his own playing. He turned to Liszt’s music. Out of the laws he found there Busoni rebuilt his technique. “Gratitude and admiration,” wrote Busoni, “made Liszt at that time my master and my friend.”18

In his younger days Liszt’s total absorption with the piano provoked comment even from his friends and supporters. Why not branch out into the larger orchestral forms, like Berlioz, instead of wasting time at a keyboard? Liszt reflected carefully on his position and produced his “Letter to Adolphe Pictet,” an autobiographical document of some importance. His abiding love for the piano, and his unshakable belief in its future, shine forth.

You do not know that to speak of giving up my piano would be to me a day of gloom, robbing me of the light which illuminated all my early life, and has grown to be inseparable from it.

My piano is to me what his vessel is to the sailor, his horse to the Arab, nay even more, till now it has been myself, my speech, my life. It is the repository of all that stirred my nature in the passionate days of my youth. I confided to it all my desires, my dreams, my joys, and my sorrows. Its strings vibrated to my emotions, and its keys obeyed my every caprice. Would you have me abandon it and strive for the more brilliant and resounding triumphs of the theatre or orchestra? Oh, no! Even were I competent for music of that kind, my resolution would be firm not to abandon the study and development of piano playing, until I had accomplished whatever is practicable, whatever it is possible to attain nowadays.

Perhaps the mysterious influence which binds me to it so strongly prejudices me, but I consider the piano to be of great consequence. In my estimation it holds the first place in the hierarchy of instruments.… In the compass of its seven octaves it includes the entire scope of the orchestra, and the ten fingers suffice for the harmony which is produced by an ensemble of a hundred players.…19

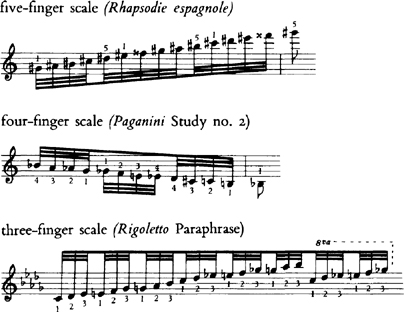

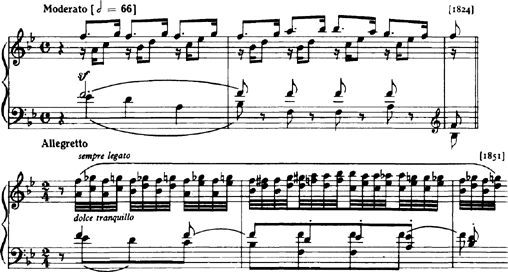

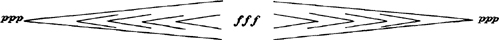

According to his own testimony, Liszt sometimes practised for ten or twelve hours a day, and much of this labour was expended on endurance exercises—scales, arpeggios, trills, and repeated notes. He set great store by the absolute independence of each finger. Every scale was practised with the fingering of every other scale (using, say, C-major fingering for F-sharp major, and D-flat major fingering for C major). No pianist can afford to neglect Liszt’s fingering. It is both imaginative and original and often looks far into the future of the keyboard. Here are three ways in which he tackled scale-building:

Particularly intriguing is Liszt’s solution to the problem of how to produce a chromatic glissando scale, which is not strictly possible on a piano keyboard.

The second finger of the right hand, nail down, plays C-major glissando. Simultaneously the five fingers of the left hand play every black key. When both hands move at the same speed, the result is a chromatic scale, glissando.20

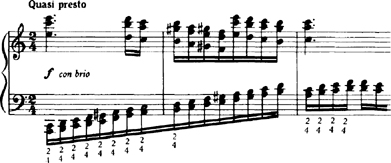

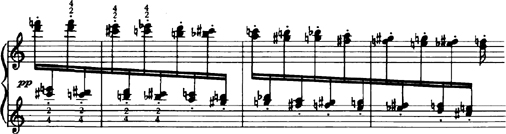

Such solutions as these, utterly bold and original as they are, bring home a central truth about Liszt’s technique. He did not conceive of a pianist’s hands as consisting of two parts of five fingers each, but as one unit of ten fingers. From his youth Carl Czerny had instilled into him the doctrine of finger equalization. But Liszt far outstripped his old mentor in the wholesale application of this philosophy. The interchangeability of any finger with any other became an ideal towards which he constantly strove. Many of the models in Liszt’s twelve volumes of Technical Studies21 are obsessed with the problem. They reached a peak of audacity in this kind of passage.

Until the hands are truly “interlocked,” such fingerings will seem perverse. The difficulty is mental, not physical. Once the pianist has grasped the notion that he does not have two separate hands, but a single unit of ten digits, he has made an advance towards Liszt. In this radical approach to the keyboard, there might be something to be said for numbering the fingers from one to ten. Incidentally, the logical outcome of the interlocking two-fingered scale shown above appeared in this shining passage from La campanella, which unfolds two dovetailed chromatic scales.

Liszt’s contemporaries were constantly amazed at his finger dexterity. He could apparently respond to any emergency. Joachim never forgot the manner in which Liszt accompanied him in the finale of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, all the time holding a lighted cigar between the first and middle fingers of the right hand.22 Lina Ramann relates a similar story. She once told Liszt that Ludwig Böhner had played fugues on the organ, in spite of two lame fingers. Liszt pondered this problem for a while, then, “with a certain tension of the muscles of the face, he seated himself at the piano and began to play a difficult fugue by Bach, with three fingers of each hand.”23 Liszt’s playing of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto in Vienna on the fiftieth anniversary of the composer’s death was the occasion for an equally impressive feat. Sometime before the performance he cut the second finger of his left hand.24 He played the concerto without using that particular finger, redistributing the notes among the remaining ones in such a way that no one was aware of the injury he had sustained.

Wherever Liszt has left us his own fingerings, then, the modern pianist does well to consider them before exhausting himself on all the alternatives. The reason is really quite simple: all the alternatives were known to Liszt and rejected by him. Consider this double-thirds passage from the sixth Paganini Study.

Its fingering is unorthodox. Yet how much simpler it is than the official conservatory fingering for such passages. The left hand forms itself into a fork, or two-fingered prong, shaking its way up the keyboard. It happens to be such a natural solution to the problem that even mediocre pianists can play the passage well. A similar procedure was followed in the first Hungarian Rhapsody, this time in the right hand.

The technique reached its apogee in such passages as the following (also in the First Rhapsody), which unrolls a pair of interlocking, double-third chromatic scales, spread across two hands. Any other fingering than that proposed by Liszt would hamper the mercurial progress of this inventive texture.

It is easy to understand why Liszt was accused of “destroying the true art of piano playing.” Old Marmontel, the doyen of piano teachers at the Paris Conservatoire, charged Liszt with “striving too much after eccentric effects.” In general, teachers were always Liszt’s enemies. He disturbed their fixed ideas, and his free, creative approach to the keyboard terrified them.

The concept of “interlocking” hands led Liszt to discover one of his most sensational effects. Known to this day as “Liszt octaves,” it symbolized clearly the difference between the old and the new schools of playing. Liszt worked up some spectacular storms with this effect. It is achieved by interlocking two sets of octaves, with the thumbs as pivots. A favoured way of practising such passages, in fact, is with the thumbs alone. A typical passage comes from the Paganini Study no. 2, in E-flat major.

For the rest, in all his technical discoveries Liszt appears to have heeded Quintilian’s maxim: Si non datur porta, per murum erumpendum (“If there is no doorway, one must break out through the wall”).

Liszt’s hands were long and narrow, and his fingers were notable for their low-lying mass of connective tissue, which gave them the appearance, in Edward Dannreuther’s graphic phrase, of being “the opposite of webbed feet.” Because his finger-tips were blunted, not tapered, they gave him maximum traction on the surface of the keyboard. These were distinct advantages. The lack of webbing between the fingers allowed of wide extensions. Liszt could take a tenth with ease. The following passage from the first version of “Gondoliera” in Venezia e Napoli (1839) was not uncomfortable under Liszt’s hand, although he later modified these stretches.

Liszt’s fourth fingers were unusually long, and that, too, encouraged him to employ fingerings difficult for normal hands. Consider this stretch between fourth and fifth fingers in Au Lac de Wallenstadt.

Almost equally difficult is the right-hand accompaniment at the beginning of Bénédiction de Dieu.

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that Liszt’s keyboard writing is idiosyncratic. He had an unerring sense of the “topography” of the piano. There is not a passage in Liszt, however difficult, that is truly unpianistic. Even Schumann and Chopin occasionally lapsed here: both wrote passages against, rather than for, the piano, passages in which the limitations of the fingers are ignored while purely musical considerations prevail. Liszt’s passage-work is often simpler to play than Chopin’s, although it may sound more brilliant. Busoni is of interest here. He wrote, “An eye-witness relates how Liszt—pondering over a cadenza—sat down at the piano and tried three or four dozen variations of it, playing each one through until he had made his choice.” The secret of that choice, Busoni concluded, was symmetry.25 A good example may be found in the opening cadenza of Totentanz. Once the basic pattern (X) has been grasped, the rest must follow.

It is often said that Liszt frowned on the use of “mechanical aids” to develop the hands. This was true only in later life. A wealth of testimony from his Weimar master classes held during the 1870s and ’80s suggests that he was bored by technique, never taught it, and was singularly unimpressed when his young “matadors of the keyboard” displayed it. In his youth Liszt’s attitude was different. As early as 1828 Liszt’s Paris studio, as we have seen, contained a piano with a specially strengthened keyboard on which it was impossible to play without effort. In 1832 he recommended to Valérie Boissier that she practise her octaves “on the brace,”26 a mahogany handrail which could be attached to each end of the keyboard and which ensured smooth lateral movements of the arms. He also suggested to the same pupil that repetitive exercises be mastered while reading a book, in order to avoid boredom. As late as the 1840s, during his European tours, Liszt was still using a dumb keyboard on long journeys.

Leaps were a particular speciality. Liszt himself clearly enjoyed taking risks, and there are times when he asks the pianist to perform some difficult feats. The following passage comes from the first version of Au Bord d’une source (1835).

Textures such as these led Henry Chorley to observe that Liszt appeared to take up more space on the keyboard than any other pianist he knew.27 Contemporary caricatures show Liszt seated at the piano with a multitude of hands and fingers jostling for a place on the keyboard. “See, he has three hands!” they used to exclaim of Thalberg. With Liszt it sometimes seemed like ten. A notorious example of rapid leaps, and one which has brought about the downfall of many a pianist, occurs in Campanella. It is not so much the distances to be traversed (at most two octaves) as the fact that the player must endure the ordeal of leaping back and forth across the void at speed for extended periods.

In order to play such a passage with security, the player must feel that the piano is an extension of his own body. You do not need your eyes to tell you that your limbs are attached to your torso. Likewise, this passage can be played blindfold by the pianist who has “internalized” the topography of his instrument. Again, the caricaturists of the time drew truer than they knew when, inspired by Greek mythology, they depicted Liszt as a piano-centaur—half man, half piano—a unique amalgam in which the instrument and the player had become indissolubly merged.

Note-repetition was another branch of keyboard technique that Liszt made his own. Ever since Sébastien Erard had perfected the double escapement, which made rapid note-repetition easy, pianists had been looking for an opportunity to explore the mechanism to the full. Liszt found it in La campanella, a piece containing quick-fire note-reiteration such as the piano had never been challenged to play before. Another splendid summit of this branch of Liszt’s art is displayed in the Tarantella from Venezia e Napoli.

Liszt here produces a magical illusion. Like some latter-day Merlin, mixing potions and casting spells across the keyboard, the wizard deludes us into thinking that the piano has been metamorphosed into a sustaining instrument of radiant beauty.

It was Liszt’s view that all keyboard configurations, however complex, could be reduced to a small group of elements—scales, octaves, leaps, repeated notes, etc.—and that if the student worked at them consistently, he could meet any challenge. Trills and tremolos Liszt placed under the category of repeated notes: a trill, that is, is merely two repeated notes alternating with one another. A method Liszt used to make his trills more brilliant was to finger them not with two, but with four fingers.

The first indication of Liszt’s technical “breakthrough” at the keyboard had come in 1838–39 with the appearance of the twelve Transcendental Studies and the six Paganini Studies. These eighteen pieces represented a treasury of keyboard resources not found in any earlier work. Such is their historical position in the world of piano music that some account of their genesis is called for.

As we have seen, Liszt was only thirteen years old when he composed the first version of the Transcendentals, in 1824.28 He now took these juvenile exercises and transformed them into works of towering difficulty. It is not clear why he chose to revise his ’prentice pieces, rather than to compose a completely fresh set of works; the transformations doubtless came into being gradually, as a natural result of his improvising increasingly complex variations over the first models. Whatever the reason, twenty-four studies were announced; once again, only twelve appeared. They were published by Haslinger of Vienna in 1839 with a dedication to Carl Czerny, and were called Grandes Etudes. A review copy found its way into the hands of Schumann, who astutely observed their connections with the juvenile pieces, overlaid though they are with monstrous technical complexities, and described them as “studies in storm and dread for, at the most, ten or twelve players in the world.”29

It was partly as a result of playing his Grandes Etudes in public, under widely varying circumstances, that Liszt revised them yet again (after his official “retirement” from the concert platform in 1847), smoothing out their more intractable difficulties. He brought out this third version in 1851, under the generic title Etudes d’exécution transcendante, and again dedicated them to his old master Carl Czerny, “from his pupil, in gratitude and respectful friendship.” At the same time Liszt added programmatic titles to all but two of the individual numbers. The original tonal connections (first laid down in the juvenile set) were meanwhile preserved.30

2. Molto vivace (A minor)

3. Paysage (F major)

4. Mazeppa (D minor)

5. Feux-follets (B-flat major)

6. Vision (G minor)

7. Eroica (E-flat major)

8. Wilde Jagd (C minor)

9. Ricordanza (A-flat major)

10. Allegro agitato (F minor)

11. Harmonies du soir (D-flat major)

12. Chasse-neige (B-flat minor)

Modern scholarship has done a disservice to Liszt by suppressing the two earlier versions, arguing that they do not represent Liszt’s final thoughts.31 For Liszt, however, a composition was rarely finished. All his life he went on reshaping, reworking, adding, subtracting; sometimes a composition exists in four or five different versions simultaneously. To say that it progresses towards a “final” form is to misunderstand Liszt’s art. Entire works are “metamorphosed” across a span of twenty-five years or more, accumulating and shedding detail along the way. The famous F-minor Study, for example, originally (1824) took this form.

In the second (1838) version it has been transformed into a work of prodigious complexity.

Later still (1851), Liszt reformulated the texture of bar 3 (and all the others modelled on it) and notated it thus:

The transformations in Feux-follets are equally remarkable. Compare the juvenile model with the highly developed concert study which later sprang out of it. The one version shimmers behind the other, and the moment the player knows it his performance is bound to be affected.

In the Transcendentals Liszt really unfolds a part of his musical autobiography in public: Liszt the supreme virtuoso openly reminisces about Liszt the youthful prodigy. It may not be essential to learn the early models before one plays the Transcendentals well. But it will certainly colour the player’s attitude towards them, in a positive sense, and will bring him more closely into line with Liszt’s own attitude towards them, if he hears the Transcendentals over that same musical background against which Liszt himself composed them.

The modern pianist may disparage Liszt’s studies, but he should be able to play them. Otherwise he admits to having a less than total command of the keyboard. Paradoxically, the biggest enemy of the Transcendentals is not the pianist whose technique is too bad to play them, but the pianist whose technique is only just good enough to do so. The former is instantly exposed for what he is: incapable. The latter, however, gamely attacks all the difficulties but leaves behind him a battlefield in which the piano and the pianist have totally exhausted themselves in physical combat. Such pianists give the Transcendentals a bad name. They create the impression that Liszt has demanded too much of the piano when he has merely demanded too much of them. All they succeed in doing is to communicate the music’s difficulties. What the Transcendentals require, above all, is a pianist whose technique is so advanced that he succeeds in communicating their simplicities.32 Only then will their musical attractions stand revealed. True, we are describing a pianist who not only commands all branches of keyboard technique, but has absorbed them deeply into his second nature and so placed distance between himself and the keyboard. We are describing a pianist who negotiates all difficulties with magisterial ease. We are describing a pianist for whom all things are easy, or they are impossible. We are describing the twenty-eight-year-old Liszt. What harsh words have been uttered against Liszt’s virtuosity, usually by those who could not match it! How strongly has it been attacked in the name of Art! Yet virtuosity is an indispensable tool of musical interpretation. One recalls Saint-Saëns’s telling aphorism: “In Art, a difficulty overcome is a thing of beauty.” Henri Maréchal once informed Liszt (who was by then an old man living in Rome) of the disgust he had felt at seeing an “imbecile pianist” play the Rigoletto Paraphrase in a difficult arrangement for the left hand. This showman had had the nerve to take out his silk handkerchief with his right hand and blow his nose in the middle of the piece, so that the audience might see that only the left hand was working. As Maréchal was telling Liszt that such antics were fit only for the fairground, Liszt gently squeezed his arm and said with a smile, “My dear child, for a virtuoso that is necessary! It is absolutely indispensable.”33

The background to the six Paganini Studies is less complex. Liszt wrote these pieces under the influence of the great violinist whose name they bear. Five of them are transcriptions from Paganini’s Twenty-four Unaccompanied Caprices, epoch-making works which raised violin playing to a new level. (It was no accident that Liszt turned to these particular pieces for his transcriptions, which were a constant reminder of the sort of goals he had set himself on the piano.) The remaining item is La campanella, a set of variations on the well-known tune of that name which Paganini had used in the Rondo of his Violin Concerto in B minor. When Liszt first published these six studies, in 1840, he gave them the title “Etudes d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini.” Eleven years later he revised them, together with the Transcendentals, and provided a new title, Grandes Etudes de Paganini. The six items are:

2. E-flat major (scales and octaves)

3. G-sharp minor, La campanella (leaps and repeated notes)

4. E major (arpeggios)

5. E major, La Chasse (thirds and sixths)

6. A minor (theme and variations)

Again, a comparison between the two versions is instructive. The conscientious player, moreover, will want to consult Paganini’s violin originals and see for himself how Liszt has achieved his transfers. Typical of his procedure is the Study in E-flat major. Paganini’s original is an exercise in scales and double-stops. The problem posed by Paganini is how to switch effortlessly from the one technique to the other.

Liszt does far more than transfer these notes to the keyboard. He transfers the problem as well, reformulating it in pianistic terms.

How to jump from the last note of the scale to the chord immediately following? That is not Liszt’s problem; it is Paganini’s. Liszt has simply incorporated it into his transcription as faithfully as he can, placing physical obstacles on the keyboard which match the ones experienced on the violin. By handicapping the pianist’s right hand with double-thirds and a flying leap to the other end of the keyboard, Liszt is attempting to translate an essential technical point in Paganini’s music. When Liszt revised this study he introduced many simplifications which, on the whole, make it “speak” more effectively. The same passage in the final version (1851) unfolds thus.

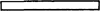

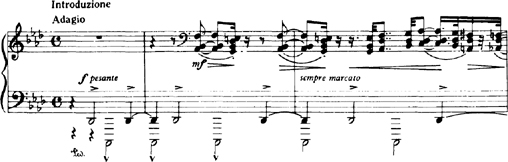

During the 1830s and ’40s Liszt developed some unconventional marks of expression, presumably because the ones currently in use were not subtle enough for his needs. Thus a single straight line over a group of notes (———) indicated a ritenuto. An oblong box ( ) indicated an accelerando. Both symbols were used in the first version of Ricordanza (1839).

) indicated an accelerando. Both symbols were used in the first version of Ricordanza (1839).

Another symbol was the double line with open ends ( ), which stood for an agogic accent. The piece called Lyon (1834) contains many examples of this expressive device.

), which stood for an agogic accent. The piece called Lyon (1834) contains many examples of this expressive device.

Although these symbols, which have the merit of simplicity, gave Liszt exact control over tempo rubato, he later formed the view that such decisions are best left to the player, and dropped them. They are of interest chiefly because they tell us how Liszt himself may have played. Equally indicative of his personal interpretations are his unusual dynamic markings. Liszt often placed a single stress mark over two or more notes simultaneously. These “multiple accents” are found, for example, in Venezia e Napoli.

Even a simple crescendo or diminuendo could be transformed by Liszt into a vehicle of great expressive power. He once told Valérie Boissier to practise crescendos like this:

This telling effect is captured to perfection by the symbol that represents it, and renders descriptive comment superfluous.

Closely allied to Liszt’s expression marks is his pedalling, which is occasionally both daring and futuristic. At a time when his contemporaries still regarded the sustaining pedal as a special effect, to be used with caution, Liszt perceived in it the very soul of the piano, without which the instrument dies. He realized the great advantage the pedal gives to the player in freeing his hands to do other things. Not least was he intrigued by the endless possibilities of mingling “foreign” harmonies in new combinations. Ever since Debussy and the Impressionists it has been accepted that clarity in piano texture is not always a virtue, that deliberate blurring and clouding of the harmonies is a genuine musical effect. In Liszt’s day this was a novel attitude. Accordingly, such pedal markings as we see at the beginning of Funérailles were without precedent; there is nothing to match them in Chopin or Schumann. The player who lacks the courage to keep the pedal down may produce a “cleaner” sound, but he will lose the noise and clangour of funeral bells which build up to a deafening roar. If he loses that, he loses the piece.

Unlike his contemporaries, Liszt was interested in the use of the soft pedal as an expressive device. In his early paraphrase on Auber’s La Fiancée he even indicates that both pedals are to be used simultaneously, casting a soft veil over the timbre.

Liszt’s notation is worth special study; it is often highly original. Since his compositions frequently arose from his improvisations, his notation occasionally assumes a spontaneous, almost wayward appearance. It must sometimes have been a problem for him to find a form of notation that perfectly matched his free-ranging creations. In the first Apparition (1834) a temporary lull in the music produces a similar lull in the notation.

Liszt heard, and he wrote what he heard. Likewise, he frequently unfolded his keyboard music on three (sometimes four) staves in order to avoid overcrowding and make his intentions clearer. His arrangement of Schubert’s Mélodie hongroise in E-flat major contains a typical example, whose left hand, incidentally, offers an object lesson in note-distribution.

By contrast, Liszt unfolded an entire piece on one stave alone, without ambiguity, in his E-major Paganini Study.

In his visionary Harmonies poétiques et religieuses (1834) the young Liszt produced an advanced, asymmetrical effect worthy of Bartók. The numerical divisions are Liszt’s own, and he clearly thought them essential for a correct rendering of this problematic passage.

What is the true time signature of the first bar? It is characteristic of Liszt to leave the question open. For the rest, notation does not produce music; music produces notation. Notation’s sole function is to symbolize the “sonic surface” of the composition which lies behind it; and even when it functions well, it needs must carry out its task imperfectly. The evidence lies everywhere to hand. How often have we heard performances (especially of Liszt’s music) in which the notes are all there but the piece is missing?

Liszt’s operatic paraphrases happen to be important in the history of keyboard notation. To condense an operatic score (soloists, chorus, and orchestra) into a viable piano texture need not be difficult. To transform that texture from a dull piano reduction (a dead copy of the original) into a living composition calls for a touch of the magician’s wand—with poetic licence, roulades, diamond-bright cascades, and even the occasional eruption of flame and fire—to cast a spell over the keyboard and persuade it to illuminate by suggestion the creative spirit of the original. A perennial problem in this kind of work is the clear separation of melody and accompaniment. Liszt’s favoured solution was to print his notation in two different shades of typeface—light and bold—so that the player is at once informed how to distribute his tone. Nowadays this is commonplace, in Liszt’s day it was new. The Rigoletto Paraphrase offers a good example.

This separation of melody and accompaniment was perfectly understood by Liszt. However complex the ornamentation, it was subordinated to the composition as a whole. His great pupil Moriz Rosenthal has told us that under Liszt’s hands, “the embellishments were like a cobweb—so fine—or like the texture of costliest lace.” The same cannot be said of Liszt’s would-be imitators, who frequently vulgarized these compositions by “bringing out” the difficulties inherent in the embellishments in a misdirected effort to score a public ovation. After Liszt’s death the operatic paraphrases fell into neglect for fifty years. There were good historical reasons for this. The operas that they had so bravely pioneered, even popularized, were by now well known; the original, crusading impulse for playing such compositions in public was therefore diminished. But a deeper reason prevailed. The early twentieth century saw the rise of musicology, with its emphasis on “authenticity,” in which the composer’s original thought was perfectly preserved, in which every note was sacrosanct, in which the “sonic surface” of the music was reproduced as nearly as he himself envisaged it. The crime of the paraphrase now was that it was a paraphrase. It was not interested in preserving the “original thought”; it changed music’s notation with impunity; it lacked reverence for the “sonic surface” of a work; indeed, it often flitted about, chameleon-like, donning the most far-flung acoustic disguises, lording it over territory it had no business to occupy. Liszt’s sixty-odd paraphrases, out of temper with the times, were hushed up and forgotten. An inimitable treasury of piano music was silenced by prejudice. It never seemed to occur to our forefathers that every opera has an overture. And what are the best overtures but arrangements of the themes of the operas they precede? Brahms, no Liszt admirer, used to maintain that in Liszt’s old operatic fantasies was to be found “the true classicism of the piano.” It is in this spirit that they have been revived in modern times, and the best of them—Norma, Rigoletto, and Faust—are likely to remain in the repertoire for as long as the operas after which they are modelled.

The bigger effects in Liszt’s music called for a large hall to contain them. We recall that it was Liszt who took the piano out of the salon and placed it in the concert hall. When, as early as 1837, he gave a recital before three thousand people in the Scala opera house, he was democratizing the instrument. Strange to say, in order to achieve this worthy end he had to overcome much prejudice. There were many musicians whose thinking was rooted in the eighteenth century and who regarded the piano—much as they had regarded the harpsichord before it—as a chamber instrument meant to be played only before a small circle of connoisseurs. Chopin, Hummel, and Moscheles had all made their reputations in that way. When Chopin played in the salons of Paris before a select audience drawn from high society, it was on the silvery-toned Pleyel with its light action that he gave his incomparable performances. Liszt had often played the Pleyel and found it wanting: he scathingly described the instrument as “a pianino.” The seven-octave Erard, with its heavier action and larger sound, was more congenial to him. The morning after his Scala recital, the twenty-six-year-old pianist wrote a letter to Pierre Erard expressing his satisfaction with the instrument.

Let them not tell me any more that the piano is not a suitable instrument for a big hall, that the sounds are lost in it, that the nuances disappear, etc. I bring as witnesses the three thousand people who filled the immense Scala theatre yesterday evening from the pit to the gods on the seventh balcony (for there are seven tiers of boxes here), all of whom heard and admired, down to the smallest details, your beautiful instrument. This is not flattery; you have known me too long to think me capable of the least deception. But it is a fact, publicly recognized here, that never before has a piano created such an effect.34

This raises the question of Liszt’s own interpretations. By all accounts they were unfettered by “performing tradition,” especially during his days as a touring virtuoso. He continually sought out new ways of playing old works. “The letter killeth but the spirit giveth life” was his watchword. He would try to penetrate to the very heart of a composition, playing it through in a variety of different ways until he thought that he had divined its true meaning. This sometimes led him into exaggeration and made him the target of criticism. Once, during a performance of Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata (with Ole Bull), such liberties were taken with the interpretation as to “call forth the disapprobation of the audience.”35 One wonders what exactly took place. We do well to put such matters into historical perspective. “Classical” playing was a discovery of the Romantics. Beethoven, that is to say, did not play his music classically.36 What in the profession is nowadays called fidelity to the text was hardly fostered until the second half of the nineteenth century, when it became associated with the “restrained” performances of such artists as Clara Schumann and Joachim. Today, of course, it has become dogma. Liszt was deeply concerned by this trend, which he regarded as a denial of the player’s artistic personality. He aptly called it the “Pilate offence”—washing one’s hands of musical interpretation in public37—and he would have nothing to do with it. There is no doubt that in his youth his performances were often considered unconventional, and he may well have played fast-and-loose with the text when the Gypsy in him stirred. We know from the lessons he gave to Valérie Boissier that he viewed the entire question of tempo in a liberal light. “I don’t play according to measure,” he once told her. “One must not imprint on music a balanced uniformity, but kindle it, or slow it down, according to its meaning.”38 It was the same during the Weimar years with conducting. He considered it demeaning for the conductor “to function like a windmill.” Liszt indicated phrasing and tempo through very general gestures. He was fond of making a nautical analogy: “We are helmsmen, not oarsmen.”39 Sometimes his helmsmanship led him to chart a dangerous course and sail his ship towards treacherous waters. Charles Hallé once heard him tack the finale of Beethoven’s C-sharp minor Sonata (op. 27) onto the Variations of the one in A-flat major (op. 26), without any break, and was offended by such a disrespectful approach to the classics.40 But as Liszt matured, his attitude towards interpretation modified. We have the testimony of such witnesses as Berlioz, Wagner, and von Bülow that once Liszt was out of earshot of the great public, his Beethoven performances were faithful marvels of re-creative beauty.41 When von Bülow dedicated his edition of the Beethoven sonatas to Liszt (the results of “the fruits of his teaching”), he was not merely paying his respects to his former master; he was also acknowledging Liszt’s supremacy as an advocate and interpreter of Beethoven. But even in Liszt’s twilight years his playing was not entirely predictable. He lived by the maxim “Tradition is laziness.” Whatever doubts still linger today about Liszt’s cavalier attitude towards the printed page are largely dispelled the moment we consult his editions of Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, and others. There is not a single case of bowdlerization. All adhere faithfully to the basic text,42 and the degree of “touching up” which Liszt allows (e.g., in the domain of dynamics, phrasing, and pedalling) is not extreme by nineteenth-century standards. Those who object to any licence in this field are free to dispense with Liszt’s editions altogether, but they should not forget that after a hundred years these volumes have themselves become important tools of research, offering one of the few direct insights into how Liszt might have interpreted the classics. After all, each piece is different and makes different demands. Liszt’s saying, “There is music which comes of itself to us, and there is music which requires us to come to it,”43 is illuminating, since it lays down a central distinction of use both to editors and players alike. The important thing, of course, is to get the distinction right.

1. Der Humorist, November 22, 1839.

2. ACLA, vol. 1, p. 405.

3. Tomášek, in his autobiography, claimed that Dussek had already positioned his piano in this way, the better to show off his beautiful profile. Dussek did not do this consistently, however, and in any case his career had no lasting impact on the history of piano playing. Liszt appears to have been unaware of Dussek’s tentative reforms when he came to the conclusion that one must not only play the piano but “play the building,” and to that end he experimented with the placement of the instrument until he got it right. Martainville’s press notice of the young Liszt’s Paris concert in 1824 is worth re-reading, since the disadvantage of having the end of the piano pointing towards the public (its usual position) is there made plain. See p. 100.

4. RFL, p. 41ff.

5. ACLA, vol. 1, p. 311.

6. See, for example, Buchner (BLB, p. 93) on his Prague recitals of 1846 and Stasov (SSEM, p. 121) on his St. Petersburg recital of 1842. At his inaugural concert in Vienna on April 18, 1838, Liszt had the misfortune to wreck three pianos in succession. He had borrowed Thalberg’s Erard grand for this important occasion but strained the action during a performance of Weber’s Concertstück. A Viennese Graf was then pushed into position for him. Less than a quarter of the way through the Puritani Fantasy, two brass strings snapped. Liszt, by now exasperated, personally dragged a third instrument (another Graf) from a corner of the stage and plunged into a performance of his Transcendental Study called Vision. Before he had reached the closing chord, two more strings had snapped beneath his powerful fingers. (WFWB, pp. 93–94.) During Liszt’s stay in London in the summer of 1840, the periodical John Bull (May 3) carried an advertisement informing its readers that “each piece” to be heard in Liszt’s first concert on May 8 “will be played on a separate Grand Piano, selected by himself from Erard’s.” Since he played at least four solo items on that occasion, the stage must have been jammed with keyboards.

7. RLL, pp. 87–88.

8. LLB, vol. 1, pp. 35–36. As we have seen, Liszt did not receive the Legion of Honour until five years later (n. 4 on p. 146). Concerning the French love of decorations generally, he later wittily observed, “In France one must go about with a decoration. One is less noticeable on the boulevards.” (Le Moniteur à Paris, March 19, 1886.)

9. RLKM, vol. 2, p. 186. Stasov dismissed this anecdote as “a ridiculous fairy-tale.” The tsar, he said, never arranged concerts. (SSEM, p. 136.) Liszt’s first visit to St. Petersburg, however, did coincide with the annual Lenten Concert for the veterans of 1812. He did not participate in that concert, but pointedly gave other charity concerts while in Russia. For further comments of Liszt on Tsar Nicholas, whom he grew to detest, see LLB, vol. 2, p. 335, and LLB, vol. 3, p. 129.

10. BALV, vol. 3, pp. 405–6. This amusing exchange was confirmed by Felix Lichnowsky, who later told Liszt, “The whole city is in a flutter, people speak only of this affair.” (LBZL, vol. 1, p. 33.)

11. SSEM, pp. 127–28.

12. “Genius has obligations.”

13. CMGM, vol. 2, p. 245. See also Archives of the Grand Duchy of Thuringia, vol. 13, p. 304.

14. See the letter of thanks from the Hamburg City Council (WA, Überformate 129, 1M).

15. ACLA, vol. 2, p. 246.

16. LLB, vol. 1, p. 257.

17. Le Nouvelliste, Marseille, July 31, 1844.

18. BEM, p. 86.

19. RGS, vol. 2, p. 151; CPR, p. 135.

20. Liszt once told Olga von Meyendorff, “For your glissando exercises I once again advise you to use only the nail, either of your thumb or of your index or third finger, without even the tiniest area of flesh” (Liszt’s emphasis). (WLLM, p. 390.)

21. WTS.

22. MJ, p. 70.

23. RLKM, vol. 1, p. 166. Ludwig Böhner was the eccentric real-life model on whom E.T.A. Hoffmann based his character “Kapellmeister Kreisler,” later to become a source of musical inspiration to Schumann in his Kreisleriana.

24. Not the right hand, as the earlier biographies have it. Liszt corrected this mistake in his own copy of RLKM, vol. 1, p. 166 (WA, Kasten 352). The cut occurred while Liszt was being shaved by his valet, Spiridon Knézéwicz. It was “completely my own fault,” wrote Liszt. “I was recommending something to Spiridon while he shaved me and, stupidly, raised my left hand too high—and have learned to esteem even more the excellence of his razor.” (LLB, vol. 7, p. 168.)

25. BEM, p. 155.

26. BLP, p. 65. Symbolic of the piano’s increased popularity during the 1820s and ’30s was the meteoric rise to prominence of J. B. Logier and his invention of the “Chiroplast”—a complex mechanism of brass rods and rails for disciplining ’prentice hands at the keyboard—which ruined many a promising career before it had properly started. Logier subsequently developed a system of mass piano teaching based exclusively on its use, which allowed him to coach up to a dozen beginners simultaneously. Since they all paid him simultaneously as well, Logier soon became rich and opened “Chiroplast instruction centres” in most of the large cities of Europe (including Berlin, Paris, London, and Dublin), laying the foundations of a reputation as a piano teacher which the results hardly seemed to justify: not one pianist of stature was produced by this method. Among the advocates of the Chiroplast was Kalkbrenner, whose notorious handrail was clearly modelled on Logier’s invention. Even the young Liszt was swept up by the handrail and recommended it to his pupils, although he later abandoned such advice, once he understood the harm that could flow from it.

27. Chorley left a compelling account of Liszt’s total command of the keyboard in CMM, pp. 45–51.

28. See pp. 118–19.

29. NZfM, no. 11, 1839.

30. See p. 118. It is not generally known that Liapunov, a Liszt admirer, also composed a set of Transcendental Studies, which complete Liszt’s key-scheme, starting in F-sharp major (the next key in Liszt’s descending spiral). He dedicated his pieces to the memory of Liszt.

31. See, for example, the editorial preface to NLE.

32. Friedheim once reported Liszt as having remarked, “To be able to play Beethoven well, a little more technique is required than he demands.” Liszt might well have been speaking of his own music.

33. MRS, pp. 111–12.

34. BQLE, p. 10. See also PMPE, p. 97, in which Liszt expresses himself vehemently against the Pleyel pianos provided for his concerts in Bologna and Florence in 1838: “The keyboard is prodigiously uneven, and the bass, middle, and upper registers are all terribly muffled.” The Bologna instrument he described as “despicable.” In despair, he borrowed a Streicher from Prince Hercolami, on which he completed his concert engagements in Bologna. Erard, it seems, could not always keep up when Liszt set out on his travels.

35. Musical World, London, June 9, 1840. A few days earlier (June 1) Henry Reeve had heard Liszt play the same sonata with Batta at a private gathering in London “en doublant les passages.” (RML, vol. 1, p. 117.)

36. SBLB, p. 413. Ries, Cramer, Tomášek, and others all testified to Beethoven’s unpredictable performances of his own music. Cherubini characterized his playing as “rough.”

37. LLB, vol. 1, p. 258.

38. BLP, p. 35.

39. RGS, vol. 5, p. 232. “Wir sind Steuermänner und keine Ruderknechte.”

40. HLL, p. 38.

41. Count Apponyi, who was present at Wahnfried in the 1870s when Liszt performed the slow movement of the Hammerklavier Sonata, has described the impact his playing had on Wagner: “When the last bars of that mysterious work had died away, we stood silent and motionless. Suddenly, from the gallery on the first floor, there came a tremendous uproar, and Richard Wagner in his nightshirt came thundering, rather than running, down the stairs. He flung his arms round Liszt’s neck and, sobbing with emotion, thanked him in broken phrases for the wonderful gift he had received. His bedroom led onto the inner gallery, and he had apparently crept out in silence on hearing the first notes and remained there without giving a sign of his presence. Once more, I witnessed the meeting of those three—Beethoven, the great deceased master, and the two best qualified of all living men to guard his tradition. This experience still lives within me, and has confirmed and deepened my innermost conviction that those three great men belonged to one another.” (AAM, pp. 100–101.)

Liszt tells us, incidentally, that he had played the Hammerklavier Sonata from the age of ten, “doubtless very badly, but with passion—without anyone being able to guide me in it. My father lacked the experience to do it, and Czerny feared confronting me with such a challenge.” (LLB, vol. 7, p. 164.)

42. See, for example, Liszt’s preface to his performing edition of the Schubert sonatas (1870), which is a model of correct musicological practice, placing before the player the various typographical symbols used to distinguish Schubert’s original text from Liszt’s (comparatively few) editorial suggestions.

43. RC, p. 27.