Liszt has created a madness. He plays everywhere and for everyone.

ALEXIS VERSTOVSKY1

With the first leg of his European tours behind him, Liszt reflected on three salutary experiences. First, it was possible to lose large sums of money as a pianist. Second, it was not always wise to rely upon local amateurs to administer one’s concerts. Poorly tuned pianos, inadequate concert halls, bad advertising, chaotic travel and hotel facilities—these were mundane matters, but they could mean the difference between success and failure. Third, and perhaps most important, Liszt (as his correspondence amply testifies) was lonely on his tours and felt the need for a convivial travelling companion. A solution to all three problems had to be found if the tours were to continue. As far back as November 1839 he had foreseen the necessity of appointing a personal secretary and had given the job to a certain Mihály Kiss (recommended to him in Pest), who had proved to be incompetent.2 His trusted pupil Hermann Cohen temporarily took over the running of Liszt’s affairs and vanished with 3,000 francs.3 We then find Liszt writing to his Austrian friend Franz Ritter von Schober:

Would you see any great difficulty in joining me somewhere next autumn—at Venice, for example—and in making a European tour with me? Answer me frankly on this matter. And once more the question of money need not be considered. As long as we are together (and I should like you to have at least three free years before you) my purse will be yours, on the sole condition that you undertake the management of our expenses.…4

Schober, who would have made an ideal secretary, was unable to accept. It was Marie d’Agoult who finally solved the problem. In August 1840 she wrote to Liszt from Paris saying that she had just interviewed someone whom she thought ideal. His name was Gaëtano Belloni, and he entered Liszt’s service in February 1841. For the next six years Belloni travelled the length and breadth of Europe with Liszt. He became the chief architect of Liszt’s performing career. The huge success of the visits to Berlin and St. Petersburg, and of the great tour of 1844–45 across the Iberian Peninsula, was due largely to Belloni’s efforts. Heine dubbed him “Liszt’s poodle,”5 but he was much more than that. Manager, secretary, and general factotum, Belloni also became a close friend. Liszt frequently charged him with delicate family commissions, involving the welfare of his children, his mother, and his financial investments. It is one of the minor ironies of Liszt biography that while so many people who scarcely knew Liszt rushed into print with their fleeting impressions, Belloni, his inseparable companion for six years, never kept a diary and never wrote his memoirs. The loss of such a priceless wealth of detail as only Belloni could have bequeathed to posterity has to be lamented.6

Liszt arrived back in Paris from his tour of Britain in mid-March 1841, and remained in the French capital throughout April. He made several concert appearances during this time. The most noteworthy occurred on March 27, when he gave a solo recital in the Salle Erard and played his newly composed Reminiscences on Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable. Such was the success of this work that it led to the famous incident on April 25 at a fund-raising concert for the Beethoven memorial. This all-Beethoven programme featured the Emperor Concerto with Liszt as soloist and Berlioz conducting. The audience would not allow the concert to proceed, and noisily clamoured for a repetition of Robert, leaving Liszt with no alternative but to oblige while Berlioz and the orchestra stood idly by. Richard Wagner was at this concert, reviewing the event for the Dresden Abendzeitung,7 and he was offended by the abrupt insertion of this flashy work. “Some day,” he wrote, “Liszt in heaven will be summoned to play his Fantasy on The Devil before the assembled company of angels.” The very next day, April 26, Liszt attended a recital given by Chopin in the Salle Pleyel. For months Chopin’s admirers had been urging him to make one of his rare, reluctant appearances, and he had finally agreed.8 Chopin played, among other things, his F-major Ballade, his C-sharp minor Scherzo, and some studies. The event should have been covered by Ernest Legouvé, the regular critic for the Gazette Musicale, but Schlesinger allowed Liszt to write the review instead. When Chopin heard this news he was apprehensive. Legouvé told him not to worry, adding, “He will make a fine kingdom for you.” “Yes,” replied Chopin, “in his empire.” Chopin’s fears were groundless. Liszt’s long article9 was highly flattering and full of admiration for Chopin’s playing.

One of Liszt’s close companions during 1841 was Count Felix Lichnowsky, an idealistic young man of twenty-six and the nephew of Beethoven’s famous patron. Lichnowsky had come forward after one of Liszt’s concerts in Brussels in February of that year and had attached himself to the famous pianist. Later he had accompanied Liszt on his travels through the Rhineland, where Liszt had given concerts to raise more money for the Beethoven statue. Lichnowsky, who was heir to vast domains in Silesia and East Prussia, with a fortress castle at Krzyzanowitz, had been cut off by his family for his liberal political views and was now in financial difficulties. Liszt generously helped him out with a loan of 10,000 francs and felt amply rewarded by the friendship of such a warm and cultivated man. During their trip through the Rhineland, Liszt and Lichnowsky came across a near-deserted island in the Rhine called Nonnenwerth. Located in the Siebengebirge district, near Bonn, Nonnenwerth was steeped in romance and mystery. According to an old German legend, Roland of Roncevaux had died of love there. A half-ruined convent, a chapel, and a few fishermen’s huts were now the only dwellings. The convent was run as a small hotel, but there were hardly any guests. It was an ideal summer retreat. Here Liszt could compose, practise, and plan the next phase of his concert tours in tranquillity.10 He negotiated a lease on the island, entitling him to live on Nonnenwerth for three years. A piano, manuscripts, and furniture were floated across by ferryboat. Liszt then wrote to Marie telling her of this Rhineland paradise. She was not at first enthusiastic. Their “reconciliation” in England the previous year had ended unhappily. “I’ll doubtless come to the Rhine,” she wrote cautiously, “if it’s the only way of seeing you, but it’s the worst arrangement for me because it’s the one which will cause the most repercussions and I’ll look as if I’m running after you or Felix.”11 Nevertheless, she travelled from Paris and arrived at Nonnenwerth in August 1841. She registered at the hotel under an assumed name, calling herself Madame Mortier-Defontaine, and occupied the quarters formerly belonging to the abbess of the convent. The lovers also spent the summers of 1842 and ’43 on the island. Marie wrote to Sainte-Beuve in Paris:

Every day I see from my window ten or twelve ships passing up and down the river. Their smoke fades away in the branches of the larches and poplars. None of them stops! Nonnenwerth and its island recluses have no business with the rest of humanity!12

Nonnenwerth was to be their last home together. Neither entertained any illusions about their dying love-affair. Baroness Czettritz, their nearest neighbour, painted a touching portrait of the old lovers. “Liszt is able to compose only when Madame d’Agoult is near him. He seats himself by her, sings or plays to her the notes he has scattered on paper. When he gets up he beseeches her to be diligent, then she writes until one o’clock in the morning.”13 It is the old picture of Marie as Liszt’s muse. George Sand’s description of the couple was truer. Her phrase “the galley slaves of love” had taken on a grim new meaning. The bonds which formerly drew them together were now transformed into chains which prevented them from drawing apart. Marie d’Agoult summed up Nonnenwerth as “the tomb of my dreams, of my ideals, the remains of my hopes.”14

Felix Lichnowsky became a frequent visitor to Nonnenwerth. He wrote a poem called “Die Zelle in Nonnenwerth,” inspired by one such visit, which Liszt set to music. A more telling souvenir of Nonnenwerth was the song “Die Lorelei,” a setting of words by Heine, which Liszt dedicated to Marie d’Agoult. The Lorelei is a steep rock that rises perpendicularly on the right bank of the Rhine. It is located at a point on the river which is difficult to navigate and is celebrated for its echo. Legend has it that a beautiful siren sits on the rock and lures mariners to a watery death with her enchanted song. Liszt must have sailed past the Lorelei many times, and he found the old legend impossible to resist. It drew from him a setting which now ranks with the finest of his seventy songs. The introduction contains a striking allusion to the opening bars of Tristan, not the first time that Liszt had stolen from the future of music.

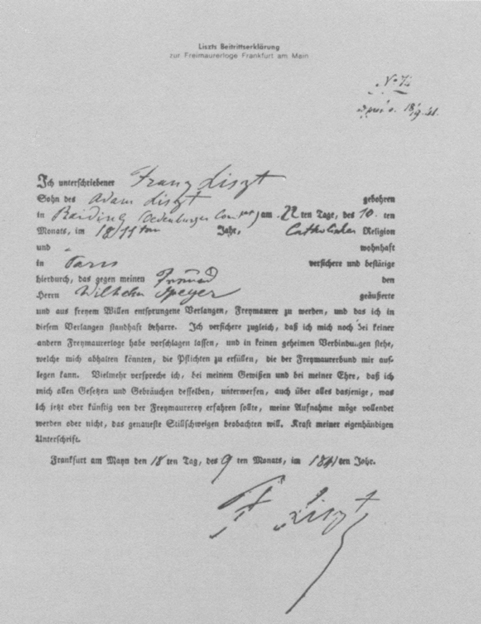

There were occasional forays from Nonnenwerth into the nearby cities of Bonn and Cologne. At Cologne Liszt caught his first glimpse of the great, unfinished cathedral and pledged himself to raise money for its building fund.15 One of these excursions was of more than passing interest. In mid-September Liszt visited Frankfurt-am-Main and became a member of the Freemasons Lodge there. His sponsor was one Wilhelm Speyer.16 Liszt signed the formal document of enrolment on September 18, 1841.17

In October Liszt and Marie left their island sanctuary. They were not to meet again for eight months. She returned to Paris, while Liszt struck out across Germany in pursuit of his performing career—to Cologne, Cassel, Leipzig, Dresden, and Weimar, a city in which he had not yet been heard and which was to change the whole direction of his career. The season would be crowned with triumphal visits to Berlin and St. Petersburg.

Liszt and Freemasonry, a document of enrolment into the Zur Einigkeit Lodge, Frankfurt-am-Main, September 18, 1841. (illustration credit 18.1)

Liszt gave his first concert in Weimar at the Court Theatre on November 29, 1841.18 The Weimarische Zeitung provided no hint of the importance of the occasion, reporting merely that “the famous pianoforte player Liszt gave … a concert that fully justified the call that went out for him.”19 Afterwards Liszt met the hereditary rulers of Sachsen-Weimar, Grand Duke Carl Friedrich and Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, the rich and powerful sister of the tsar. Maria Pavlovna, who was to become one of Liszt’s staunchest allies during his Weimar years, was very musical; she sang and even composed. Liszt’s first impressions of his future benefactors, and of the city of Weimar itself, with which his name was soon to be inextricably linked, may be found in his letter to Marie d’Agoult dated December 7, 1841.20 More important was the friendship he formed with their twenty-three-year-old son, Carl Alexander, the Grand Duke Apparent, who, as Raabe points out, at once recognized in Liszt not only “a famous pianoforte player” but someone who might help in the spiritual and artistic regeneration he planned for Weimar—a noble aspiration he was to pursue throughout the nearly fifty years of his distinguished reign. Carl Alexander wanted nothing less than the restoration of the once-proud city of Goethe and Schiller to its former glory, achieved under the benevolent rule of his illustrious grandfather Carl August, and through his vision he persuaded a number of eminent men in the arts and sciences to settle there. Could Liszt too be tempted to regard Weimar as his home? The opportunity to ask him did not present itself until the following year. Liszt passed through Weimar again in October 1842 and played to the royal family in the castle and once more in the Court Theatre. The occasion was a particularly joyous one, since Carl Alexander had just married Princess Sophie, the eighteen-year-old daughter of King Wilhelm II of the Netherlands, and the young couple were still on honeymoon. With the full approval of his parents Carl Alexander offered Liszt the title of Court Kapellmeister in Extraordinary,21 a position that for the time being carried with it few duties, demanded Liszt’s presence in Weimar for only two or three months of each year, and left him free to follow his virtuoso career wherever it led him. The arrangement was mutually advantageous: Carl Alexander had bound Liszt’s name and fame to his court, while Liszt now had an artistic haven to which he might return at will. As it happened, he did not take up full-time residence there until 1848, but even as his world tours unfolded, Weimar became for him an artistic Camelot, constantly beckoning, and his plans for its musical future were never far from his thoughts.

Some of Liszt’s concerts during the 1841-42 season were given in collaboration with the Italian tenor Giovanni Rubini, an uneasy alliance about which little is known except that it was punctuated by outbreaks of artistic temperament on both sides, and that it hardly survived the first few weeks. Having parted in Prussia, for example, Rubini and Liszt came together again for a joint appearance at The Hague before the Dutch royal court. At the conclusion of the concert the royal chamberlain presented each of them with a snuffbox. Liszt was taken aback to discover that his own was of less value than Rubini’s. “It does not suit me,” he wrote to Marie d’Agoult, “not to be put on the same level as he,” and he gave his snuffbox to Belloni.22 Perhaps he felt the snub more keenly because it followed so hard on the heels of the wild demonstrations his playing had provoked in Berlin and St. Petersburg just a few months earlier, and which should now command our attention.

Liszt arrived in Berlin just before Christmas 1841 and took up residence at the Hôtel de Russie. Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, and Spontini were there to greet him.23 Word of Liszt’s arrival spread quickly, and that same evening a group of thirty students turned up and serenaded him with a performance of his part-song “Rheinweinlied.” No one could have foreseen from this harmless reception that a storm was about to break loose. His first recital took place in the Berlin Singakademie on December 27. It included several old favourites—the overture to Guillaume Tell, Robert le diable, and “Erlkönig”—works which had been near-failures in England the previous year. This time it was different. The clamour which erupted shook the Singakademie to its foundations and set the tone for the rest of his stay. It was at Berlin that “Lisztomania” swept in. The word was coined by Heine. The symptoms, which are odious to the modern reader, bear every resemblance to an infectious disease, and merely to call them mass hysteria hardly does justice to what actually took place. His portrait was worn on brooches and cameos. Swooning lady admirers attempted to take cuttings of his hair, and they surged forward whenever he broke a piano string in order to make it into a bracelet. Some of these insane female “fans” even carried glass phials about their persons into which they poured his coffee dregs. Others collected his cigar butts, which they hid in their cleavages.24 The overtones were clearly sexual. Psychologists may have a wonderful time explaining such phenomena, but they cannot change the facts: Liszt had taken Berlin by storm, and for a pianist that was unprecedented. Liszt remained in Berlin for ten weeks. His feat of playing eighty works in twenty-one concerts has already been noted. In no other city did he make so many appearances in so brief a time.25 The Prussian royal family attended most of them. As a mark of appreciation, King Wilhelm IV bestowed on Liszt the Ordre pour le Mérite. In mid-February Liszt was elected a member of the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts.

Liszt was now accused of “playing to the gallery,” of lapsing into vulgarity. But what was he supposed to do? Cease playing? He had suddenly become the victim of his own success and hardly knew how to cope. His correspondence discloses that he was as surprised as anyone at the furore surrounding him. The fuss was entirely the fault of the Berliners. If proof be sought, it will be found in their reaction to Liszt just one year later when he returned to Prussia. Ashamed of their initial emotional outburst, they all but shunned him and turned his second visit to their city into one of the low points of the year. Yet the Liszt of 1843 was no different from the Liszt of 1842. By then, however, “Lisztomania” had moved on and was sweeping southern France. Heine saw in it the deft hand of Belloni. He spread the story that Liszt’s manager was importing the claque and paying for “ovation expenses.”26 There is no evidence for this tale, but it was too good to suppress and persists in the Liszt literature to this day.

Liszt’s sojourn in Berlin was marked by close friendships with two women of distinction. One of them was Charlotte von Hagn, the finest actress in Germany and one of the great beauties of her time. A typical Bavarian, with blond hair and blue eyes, Charlotte was twenty-one years old. She spoke excellent French, and Liszt found in her a warm and delightful companion. Vulnerable to Liszt’s chivalrous attentions, Charlotte scribbled a love-poem on the corner of her fan for him. Liszt carried it off and set the words to music.27 Seven years after their brief encounter, Charlotte, who was now married, wrote to Liszt, “You have spoiled all other people for me. Nobody can stand the comparison.”28 Liszt’s other friendship was with the formidable Bettina von Arnim, who had known both Goethe and Beethoven. Bettina was now fifty-seven years old and reflecting on her past life. Liszt had many conversations with her about these two men of genius and treasured her recollections of them.29

When Liszt finally left Berlin he was driven out of the city in a coach drawn by six white horses. Thirty other coaches followed in stately procession along the Unter den Linden. Prince Felix von Lichnowsky rode at Liszt’s side as his aide-de-camp. An escort of Prussian students, bedecked in colourful uniforms, accompanied them as far as the Brandenburg Gate. The University of Berlin suspended its sittings for the day as a mark of respect. It was a bright sunny morning on March 3, and multitudes stood in the Schlossplatz and the Königstrasse shouting “Vivat!” as Liszt drove past. King Wilhelm IV and his queen stood at the palace windows waving the procession farewell. It was as if a reigning monarch were taking leave of his people. “Not like a king, but as a king,” in Rellstab’s happy phrase.30 From Berlin Liszt proceeded to Königsberg. After giving a concert for the university, he was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Philosophy. “A slap in the face for the Berlin professors who, in their stupid pride, had denied it to him,” wrote Varnhagen von Ense.31 Concerts in Mittau and Riga followed. Liszt finally reached St. Petersburg, by way of Warsaw, in April 1842.

Liszt’s first visit to Russia could not have taken place in more favourable circumstances. He was there under the direct patronage of Tsarina Alexandra, to whom he had been presented two years earlier at Ems. There were other Russian well-wishers too. During the winter of 1839, in Rome, Liszt had played in the home of Prince Galitzine, the governor-general of Moscow, who had also pressed on him an invitation to visit Russia. Meanwhile, the Berlin newspapers had travelled ahead of Liszt, spreading news of his latest conquests. By the time he entered the imperial city of St. Petersburg his success was virtually assured. The day after his arrival, on April 4 (Old Style), he was presented to Tsar Nicholas I, who, on seeing Liszt enter the audience chamber, broke away from his generals and court officials, and advanced on him. The following dialogue ensued:

“We are almost compatriots, Monsieur Liszt.”

“Sire?”

“You are Hungarian, are you not?”

“Yes, Your Majesty.”

“I have a regiment in Hungary.”32

The dislike that soon arose between the military-minded Nicholas and Liszt has already been remarked. But even Liszt must have been rendered speechless by this tactless comment.

On April 8 Liszt gave his first concert in the great Assembly Hall of the Nobles, before an audience of three thousand people. No artist had ever played in Russia before such a vast throng. A small stage had been erected in the middle of the hall “like an islet in the middle of an ocean.” Two pianos stood on it, turned in opposite directions, so that Liszt could move from one to the other and thus face each half of the huge audience in turn. The occasion was enshrined in the reminiscences of Vladimir Stasov, the Russian critic, who attended the concert in the company of his friend the composer Alexander Serov.

As people began streaming into the hall, I saw Glinka for the first time in my life. He was pointed out to me by Serov, who had met him not long before and, of course, rushed up to him all smiles, handshakes and questions. But Glinka did not spend much time with Serov. A shrivelled old lady, Mme. Palibina (who, by the way, was an excellent pianist) began calling him.…

Suddenly there was a commotion in the crowded Assembly Hall of the Nobility. We all turned around and saw Liszt, strolling arm in arm through the gallery behind the columns with the potbellied Count Mikhail Vielgorsky. The Count, who moved very slowly, glowering at everyone with his bulging eyes, was wearing a wig curled à l’Apollo Belvedere and a large white cravat. Liszt was also wearing a white cravat and over it, the Order of the Golden Spur which had recently been given him by the Pope.33 Various other orders dangled from the lapels of his frock coat. He was very thin and stooped, and though I had read a great deal about his famous “Florentine profile,” which was supposed to make him resemble Dante, I did not find his face handsome at all. I at once strongly disliked this mania for decorations and later on had as little liking for the saccharine, courtly manner Liszt affected with everyone he met. But most startling of all was his enormous mane of fair hair. In those days no one in Russia would have dared wear his hair that way; it was strictly forbidden.

Just at that moment Liszt, noting the time, walked down from the gallery, elbowed his way through the crowd and moved quickly toward the stage. But instead of using the steps, he leaped onto the platform. He tore off his white kid gloves and tossed them on the floor, under the piano. Then, after bowing low in all directions to a tumult of applause such as had probably not been heard in Petersburg since 1703, he seated himself at the piano. Instantly the hall became deadly silent. Without any preliminaries, Liszt began playing the opening cello phrase of the William Tell overture. As soon as he finished, and while the hall was still rocking with applause, he moved swiftly to a second piano facing in the opposite direction. Throughout the concert he used the pianos alternately for each piece, facing first one, then the other half of the hall. On this occasion, Liszt also played the Andante from Lucia, his fantasy on Mozart’s Don Giovanni, piano transcriptions of Schubert’s “Ständchen” and “Erlkönig,” Beethoven’s “Adelaïde” and in conclusion, his own Galop chromatique.

We had never in our lives heard anything like this; we had never been in the presence of such a brilliant, passionate, demonic temperament, at one moment rushing like a whirlwind, at another pouring forth cascades of tender beauty and grace. Liszt’s playing was absolutely overwhelming.…34

After the concert, Stasov reports, he and his friend Serov “were like madmen.” They rushed home to capture their impressions in writing. “Then and there, we took a vow that thenceforth and forever, that day, 8 April 1842, would be sacred to us, and we would never forget a single second of it till our dying day.”

Altogether Liszt gave six public concerts in St. Petersburg during April and May. One of them was for the victims of the great fire that had devastated Hamburg. In addition he played many times at receptions given by the nobility—including Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, Prince Peter of Oldenberg, Prince Yusupov, and Count Benkendorf. He also met the great pianist Adolf Henselt, who had lived in St. Petersburg since 1838 and was now the Imperial Court Pianist. Von Lenz was present at this meeting and reports that at Liszt’s request, Henselt played Weber’s Polacca in E major. Liszt was stunned by the polished performance, given in Henselt’s inimitable fashion, sitting motionless at the keyboard, impervious to technical difficulties. “I, too, could have had velvet paws if I had wished,” Liszt remarked.35 The friendship formed on this occasion, based on mutual respect for one another’s musical gifts, survived until Liszt’s death. Liszt’s farewell concert took place in the home of Count Vielgorsky on May 16. Afterwards there was a banquet in Liszt’s honour. Among the guests were Glinka, Henselt, and von Lenz. Liszt delivered a speech of thanks, promised to return to Russia next year, and that same evening boarded ship for Lübeck.

Altogether Liszt visited Russia three times. He returned there in 1843 and again in 1847. Neither occasion matched the triumphs of his first visit. Stasov suggests that the fickle Russian public was by then under the spell of Italian opera. A more compelling reason was that on his way through Warsaw in 1843 Liszt was charged with expressing support for the Poles in their struggle for national independence from the Russian yoke, in consequence of which the great aristocratic families of St. Petersburg could not afford to be closely associated with him.36 It is a fact that on his next visit to that city Liszt was obliged to hire the small Engelhardt Hall, since he could not fill the Assembly Hall of the Nobles. His radical views were documented by Eva Hanska, the Polish mistress of Balzac, who met Liszt in St. Petersburg. He went several times to her home and she left a detailed description of the great pianist.

One day the servant walked in and announced “M. Liszt” with no more ceremony than if M. Liszt had simply been the owner of the coat he was wearing.… I rose and went towards him, stammering a few words of conventional greetings. Liszt is of medium height, thin, pale, and drawn. He has the bilious complexion belonging to people of great talent and personality. His features are regular. His forehead is less high than they show it in his portraits. He is furrowed with lines.… His eyes are glassy, but they light up under the effect of his wit and sparkle like the facets of a cut diamond.… His best feature is the sweet curve of his mouth, which, when it smiles, makes heaven dream.…37

Their conversation led them inevitably to Balzac, with whom Liszt had already become acquainted in Paris. Balzac’s novel Béatrix was then being published by instalments. The book is beyond question a fictionalized account of the love-affair of Marie d’Agoult and Liszt. Did Liszt recognize himself in this novel? Madame Hanska could not forgo the opportunity of asking him. “They wanted to break our friendship,” Liszt told her. “They tried to insinuate that he had dressed me up in a far from flattering manner under the name of Conti … but since I didn’t recognize myself in it, I didn’t accept the portrait.”38

The next stop was Moscow, where Liszt had agreed to give one concert under the aegis of the governor-general, Prince Galitzine. He was obliged to give eight, so tumultuous was his reception.39 The Moscow concerts of 1843, in fact, fared much better than the ones in St. Petersburg, possibly because Liszt was being heard there for the first time. The Muscovites also appreciated the pianist’s generosity towards them. He gave an organ recital for charity in the Protestant Church of St. Peter and Paul, raising 13,000 roubles for the Orphans Fund. And when he learned of the difficult situation of Fyodor Usachov, an actor in the Moscow theatre, he volunteered his services at a benefit concert.40 These acts were widely reported in the press and endeared Liszt to the Russian public. The climax of the visit came at the beginning of May, when he made his first contact with the Moscow Gypsies. He was utterly fascinated by the Eastern flavour of their melodies and their wild Asiatic rhythms, and he was swift to compare them with their Hungarian counterparts.41 On one occasion he became so absorbed by their performance that he forgot about his own concert that day and arrived at the hall very late. By the time he walked onto the platform, the audience had become restless. Liszt seated himself at the piano, amidst loud applause, but instead of beginning the first item on the printed programme he fell into a reverie. Then there emerged from the piano an improvisation on themes Liszt had just heard the Gypsies sing. The audience was at first puzzled, then captivated by the inspiration that flowed from the keyboard. Word soon spread that Liszt had been detained by Gypsies and had left them deeply stirred.

During this visit of 1843 the Muscovites entertained Liszt lavishly. One of these gala dinners was reported in the journal Moskvityanin in amusing terms. Liszt seemed bored by the orchestral overtures played in his honour. Then several men entered the banquet hall bearing a sturgeon almost seven feet long and weighing a hundred pounds. Liszt had never seen anything like it. He started to applaud the sturgeon, and everybody else followed suit. “The applause grew so lively that the chef, who had walked out on the stage behind his enormous artistic creation, was obliged to take bows for the insensible fish.”42

Liszt’s visits to Russia were historically important. When he first arrived there musical culture was in its infancy and run by dilettantes. This was long before the great conservatories at St. Petersburg and Moscow were established. Russian musicians had nowhere to go for their training. Glinka, Russia’s leading composer, was neglected and his epoch-making opera Russian and Ludmilla criticized on all sides by blinkered amateurs who preferred to import Rossini. Glinka himself writes well about the undeveloped state of music in Russia during the 1840s in his memoirs. So too does Stasov, a more objective chronicler; surveying the bleak landscape that passed for culture in those days, he could only exclaim, “What a time, what people!” Liszt showed a keen interest in Russian folk song and actively encouraged Russian musicians to break away from the European yoke and develop their own language. He declared Russian and Ludmilla to be a masterpiece and pleased Glinka immensely by playing through the score at sight on the piano. Liszt’s visits served as a catalyst to the Russians, who were reeling under their impact years after he left. Two generations passed and some of Russia’s best pianists were still travelling to Weimar—Siloti, Friedheim, and Vera Timanova, among others—to join his master classes. In later years few things gave Liszt greater pleasure than the emergence of “the mighty handful,” with its distinctive nationalistic speech.

Liszt left Russia in early May 1842. His sojourn had lasted four weeks. He had made large sums of money (in one week alone he earned more than 40,000 francs;43 one-quarter of this was immediately despatched to Anna Liszt in Paris for the care of his children), but the constant round of concerts, coupled with the wear and tear of travel, was taking its toll. “I feel a great tiredness of life and a ridiculous need of rest, of languor,” he wrote.44 This theme recurs with increasing regularity in Liszt’s correspondence. He was only thirty years old and already burning himself out. Nonetheless, he was back in Paris by mid-June (travelling through Central Europe at the rate of 50 or 60 miles a day), where he gave a charity concert and directed a male choir in performances of his “Rheinweinlied” and “Reiterlied” settings. The following month he went to Liège to attend the unveiling of a statue to Grétry, and then to Brussels to participate in the Grétry festival. At the end of the unveiling ceremony Liszt was publicly invested with the Cross of the Lion of Belgium.45

Liszt’s return to France did not go unnoticed by the local press. Since his departure from Paris a year earlier, the French had witnessed the amazing spectacle of “Lisztomania,” and they were determined to cut the pianist down to size. He became the object of a scurrilous attack in the columns of the Sylphide.

Liszt in Berlin, a silhouette by Varnhagen von Ense (1842). (illustration credit 18.2)

For a long time M. Liszt has been merely ridiculous. We laughed at his long hair and his great sabre. His last trip to Germany begins to make him odious. Today, this Word of the piano is vainly trying to change into a man, growing a body, hat, cane, boots, like every Tom, Dick, and Harry, sticking a pince-nez to his eyebrows and deigning to watch the crowd pass by on the boulevard.46

This notice was calculated to wound. Its wicked references to a carriage “drawn by six coal-black horses” and a bared sabre brandished before “a flock of duchesses” were thinly disguised variations on past scenes in Berlin and Hungary. They had nothing to do with anything in Paris. Paris laughed anyway. Liszt had become the butt of much satire in his adopted city.

1. VET, vol. 7, 1912.

2. LLB, vol. 1, p. 34; ACLA, vol. 1, p. 407; PBUS, p. 50. See also the Pesther Tageblatt of January 10, 1840.

3. ACLA, vol. 2, p. 183. See pp. 213–14.

4. LLB, vol. 1, p. 34.

5. HSWMB, vol. 9, p. 394.

6. See the appreciative words Liszt wrote about Belloni in his will (1860). (LLB, vol. 1, pp. 367–68.)

7. May 5, 1841.

8. George Sand is amusing on this topic. She referred to the forthcoming recital as “this Chopinesque nightmare,” and went on, “He will have nothing to do with posters or programmes and does not want a large audience. He wants to have the affair kept quiet. So many things alarm him that I suggest that he should play without candles or audience, and on a dumb keyboard.…” (Letter to Pauline Viardot, April 18.)

9. Gazette Musicale, May 2, 1841.

10. The care with which Liszt now planned his tours after the debacle in the British Isles is evident in his correspondence. In a little-known letter to Princess Belgiojoso, written from Nonnenwerth in October 1841, Liszt declared, “I have come to the Rhine in order to have a rest and to take a breather before my voyage to Russia.” That voyage was still six months distant. (OAAL, p. 180.)

11. ACLA, vol. 2, p. 153.

12. Published by Claude Aragonnès in the Mercure de France, July 1935. “You see that I am here under a pseudonym,” wrote Madame d’Agoult. “It is the beginning of fame.”

13. JFL, p. 98.

14. VCA, vol. 2, p. 70.

15. His first concert for the Dombau took place on August 22, 1841, and raised 380 thaler, 1,110 marks. (See Henseler, Das musikalische Bonn im 19. Jahrhundert, p. 178.)

16. Wilhelm Speyer (1790–1878) was a composer and violinist who had settled in Frankfurt and now owned a business there. He had founded the local Mozart Stiftung and ran a popular series of Liederkranz evenings for the performance of male-voice choruses. Liszt composed several works for Speyer in this genre (including his vocal quartets “Rheinweinlied,” “Studentenlied,” and “Reiterlied,” R. 542) and published them in 1843 “for the benefit of the Mozart Institute.”

17. Reproduced on p. 369. For more information on Liszt and Freemasonry, and his induction into the Zur Einigkeit Lodge in Frankfurt, see his correspondence with Wilhelm Speyer published in SWS, pp. 228–35. The entire question of Liszt’s connection with the Freemasons has been ably dealt with by Philippe Autexier in AML. On February 22, 1842, he was admitted to the Zur Eintracht Lodge in Berlin (WA, Überformate 120, 1M). Eighteen months later, on September 23, 1843, he was made an honorary member of the Freemasons Lodge in Iserlohn (WA, Überformate 130, 1M). Finally, on July 15, 1845, he joined the Lodge St. Johannes Modestia cum Liberate in Zürich (WA, Überformate 179, 1M). Even after he received the tonsure in 1865, Liszt retained his links with the Freemasons, and he was elected to the Zur Einigkeit Lodge in Budapest in 1870. After his death the Freemason’s Journal published an obituary notice in which it referred to “Brother Franz Liszt, on whose grave we deposit an acacia branch.”

18. See the diary of M. S. Sabinina, Zapiski, Russkii arkhiv, vol. 1 (Moscow, 1900), p. 530, for an eye-witness account of the concert. Also MFL, vol. 1, p. 768, fn. 98.

19. December 1, 1841.

20. ACLA, vol. 2, p. 182.

21. The decree is dated November 2, 1842. Although the document was issued under the direct command of the reigning Grand Duke, Carl Friedrich, the subsequent correspondence makes it clear that it was the son, Carl Alexander, who initiated this appointment, and it was to Carl Alexander that Liszt always pledged allegiance.

22. ACLA, vol. 2, p. 240.

23. ACLA, vol. 2, p. 189.

24. A. Brennglas, Franz Liszt in Berlin: Eine Komödie in drei Acten (Berlin, 1842). This singular practice was even transported to the marble halls of the court of Weimar. Liszt once threw away an old cigar stump in the street under the watchful eyes of an infatuated lady-in-waiting, who reverently picked the offensive weed out of the gutter, had it encased in a locket surrounded with the monogram “F.L.” in diamonds, and went about her courtly duties unaware of the sickly odour it gave forth—to the mystification of the rest of the royal household, who could not wait to get beyond range whenever she appeared. (BKMM, vol. 1, p. 42.)

25. The statistics may be found in Rellstab (RFL, pp. 41–44) and in the Berlin press. Nine of the twenty-one concerts were for charitable causes, including the building fund of Cologne Cathedral and the University of Berlin. Since it is of historical interest, and since it represents a major musical feat usually lost in the hullabaloo surrounding his appearances in Berlin, the repertoire Liszt played from memory during his ten-week sojourn is preserved here.

| BACH | Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in D minor; Organ Prelude and Fugue in A minor; Organ Prelude and Fugue in E minor; Prelude and Fugue in C minor (Bk. 1, “48”) |

| BEETHOVEN | Sonata in C-sharp minor; Sonata in D minor; Sonata in F minor (Appassionata); Sonata in A-flat major (Funeral March); Sonata in B-flat major (Hammerklavier); Concerto in C minor; Concerto in E-flat major (Emperor); Choral Fantasy |

| BEETHOVEN-LISZT | Scherzo, Storm, and Finale from the Pastorale Symphony; Funeral March from the Eroica Symphony; Song Cycle: Adelaïde |

| CHOPIN | Studies; Mazurkas; Waltzes |

| HANDEL | Fugue in E minor; Theme and Variations (D-minor Suite) |

| HUMMEL | Septet; Oberons Zauberhorn |

| MENDELSSOHN | Cappriccio in F-sharp minor |

| MOSCHELES | Studies |

| PAGANINI-LISZT | La campanella; Carnival of Venice Study |

| ROSSINI-LISZT | William Tell Overture; Tarantella; La Serenata e l’Orgia |

| SCARLATTI | Sonatas |

| SCHUBERT-LISZT | “Erlkönig”; “Ave Maria”; “Ständchen”; “Lob der Thränen” |

| LISZT | |

| Paraphrases | Don Giovanni (Mozart); Robert le diable (Meyerbeer); Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti); Niobe (Pacini); La sonnambula (Bellini); I puritani (Bellini); Norma (Bellini); Lucrezia Borgia (Donizetti); Les Huguenots (Meyerbeer) |

| Original works | Valse à capriccio (no. 3); “Heil im Siegerkranz” (“God Save the King”); Grande Valse di bravura; Grand Galop chromatique; Au Lac de Wallenstadt; Au Bord d’une source; Hungarian Rhapsodies; Hungarian March; Mazeppa (Transcendental Study); Hexaméron Variations |

The contemporary newspapers of Berlin do not always give keys and numbers. For example, it is impossible to say precisely which works of Scarlatti were featured. Likewise, we cannot be certain about the identity of the Chopin groups.

The strain of so much playing took its toll once again. As in Leipzig the previous year, and under somewhat similar circumstances, Liszt fell ill. He wrote to Marie d’Agoult, “You cannot imagine how I live! I have been ill for two days. Sometimes I feel as if my head and my heart would burst.” (ACLA, vol. 2, p. 191.)

26. HMB, p. 397.

27. See his song “Was Liebe sei,” R. 575(a).

28. LLF, p. 113. By 1849 Liszt was Kapellmeister to the Weimar court. Did Charlotte hope to resume their friendship? Her letter contains this pointed pun: “Sie müssen ja schon als Kapellmeister ungemein viel Takt haben!” (“As a conductor you must of course have exceptional tact.” In German Takt also means “beat” or “measure.”) Four of Charlotte’s unpublished letters to Liszt are kept in the Weimar archives (WA, Kasten 24, no. 19).

29. See Liszt’s letter to Bettina, written on March 15, 1842, after his departure from Berlin, in which he poetically describes their friendship as “a magnetic force of two natures which will, I believe, increase with distance.” (“Unbekannte Briefe Franz Liszts, veröffentlicht von Friedrich Schnapp,” Die Musik, vol. 18, no. 10, July 1926, p. 720. See also La Mara’s sketch of Bettina in LLF, pp. 119–37.

30. Eye-witness reports of the scene may be found in RFL, p. 37, and VT, vol. 2, p. 30.

31. VT, vol. 2, p. 30. The investiture was carried out by Professors Jacobi and Rosenkranz of the Faculty of Philosophy. During the ceremony Jacobi delivered a fulsome address, part of which is reproduced in KFL, pp. 160–61. See the letter of thanks Liszt wrote from Mittau, dated March 18, 1842, addressed to “The Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Königsberg.” (LLB, vol. 1, p. 46.)

32. ACLA, vol. 2, p. 211.

33. Stasov was mistaken. Liszt was never given the Order of the Golden Spur.

34. SSEM, pp. 120–21.

35. LGPZ, p. 104. The details of five of Liszt’s St. Petersburg recitals, incidentally, were published in MFL, vol 2, pp. 434–37.

36. According to Liszt, the chief of police in Warsaw sent false reports to St. Petersburg about his “Polish sympathies” and these were distorted by the Polish press. (RL, p. 401; WA, Kasten 351, no. 1.)

37. Letter dated April 13, 1843; Spoelberch de Lovenjoul collection, Chantilly.

38. The first two parts of Béatrix were published in Le Siècle in April and May 1839. They then appeared in book form in 1842, just before Liszt met Madame Hanska. Part 3 appeared in Le Messager between December 24, 1844, and January 23, 1845. In the novel Marie is portrayed as Marquise de Rochefide and Liszt as Count Gennaro Conti, an Italian musician. The marquise deserts her husband for Count Conti, just as Marie had done for Liszt. She wants to be Conti’s inspiration, to play the Beatrice to his Dante, just as Marie had wanted to do for Liszt. First-hand material about the lovers of Geneva had been fed to Balzac by George Sand while he was her guest at Nohant in the early part of 1838. As early as March 2, 1838, Balzac had written to Madame Hanska from Nohant: “Apropos of Liszt and Madame d’Agoult, she [Sand] gave me the subject of Les Galériens ou Les Amours forcés which I am going to treat, for in her position she cannot do so herself. Keep this secret.”

After the publication of Béatrix the close relationship between Sand and Madame d’Agoult was irreparably broken. Why, it may be asked, should Sand betray her old friend and behave in Balzac’s presence like a cheap gossip? It was Marie herself who brought about her own downfall. During the period 1837–39 she wrote a number of indiscreet letters to their mutual friend Countess Carlotta Marliani, the wife of the Spanish consul in Paris, in which she referred to Sand’s affairs with Mallefille and Chopin as a comedy. Carlotta showed these letters to Sand, who lost no time in punishing Marie through Balzac for her presumptuous remarks. Not content with punishment by proxy, Sand struck a blow for herself when she placed Marie in her novel Horace (1841) as Viscountess de Chailly. The portrait she painted there was a personal insult: “… she had, indeed, a nobility as artificial as everything else—her teeth, her bosom, and her heart.” Marie was deeply humiliated by the publication of Béatrix, followed so hard by that of Horace. According to Janka Wohl, Marie wept tears of rage and humiliation over Béatrix and demanded that Liszt seek satisfaction on her behalf, something he refused to do. “Is your name in it? Did you find your address in it, or the number of your house? No! Well then, what are you crying about?” (WFLR, pp. 67–68.) We may be sure that such galling experiences shook Marie’s pride and gave her the idea of later creating a pen-portrait of her own—in Nélida. And Liszt? He made the wise and sensible decision of always denying that he was the model for any fictionalized portrait whatsoever. Four years before she raised the question, then, Madame Hanska knew the answer.

39. The Moscow concerts of 1843 have never been well documented. Liszt’s opening concert took place on April 13 (Old Style) in the Bolshoi Theatre. The others occurred in swift succession on April 15, 17, 20, 22, 27, 30, and May 4. Substantial articles appeared in the Moscow press, including Severnaya Pchela, Moskvityanin, Russkii invalid, and Biblioteka dlya Chteniya. The scholar V. Khvostenko compiled a useful assembly of press notices from Liszt’s tours of Russia in 1842 and 1843, which appeared in the November and December 1937 issues of Sovietskaya Muzyka. From this source we learn that for his Moscow concerts Liszt played on a newly invented “orchestral piano” by Lichtental, which achieved massive effects by means of octave couplings.

40. DFL, vol. 4, 1911, p. 81; vol. 7, 1912, p. 65.

41. Liszt mentions this visit to the Moscow Gypsies in his book Des Bohémiens (RGS, vol. 6, pp. 145–51).

42. Moskvityanin pt. 3, no. 5, 1843; SSEM, p. 133.

43. The difficulty of translating Liszt’s concert fees (which he earned in a variety of different currencies—pounds, francs, gulden, thaler, roubles, etc.) into sums comprehensible to the modern reader is impossible to resolve. The twin phenomena of inflation and floating exchange rates will forever mask the true value of money in times past. Some social historians have dealt with this sort of problem via concordance tables which convert money into goods (e.g., 100 pounds equals a house, 500 francs equals a field of barley) in an attempt to produce an “absolute” standard, but this only leads to further complications, as the cost of goods differs from country to country. The biographer is wise to follow the example of the legendary Scots divine who, confronted by a fatal flaw in the logic of his sermon, told his congregation to “stare this difficulty in the face and pass by on the other side.”

44. ACLA, vol. 1, p. 213.

45. The ceremony took place on July 18, 1842, in the main public square of Liège. It is amusing to note that Liszt received the cross in company with his old critic Fétis, who was now a director of the Brussels Conservatoire of Music.

46. La Sylphide, vol. 6, 1842, p. 59.