WHEN JAPAN ENTERED THE FRAY of global politics at the end of the nineteenth century, its new nation builders were convinced that a national literature, which presupposed a common and continuous national language, would be indispensable to the construction of a unified nation-state. In this context, The Tale of Genji was to become a crucial text.

From a global perspective, the publication in 1882 of an English translation of The Tale of Genji was an epoch-making event. The translation was an abridged version of the first seventeen chapters of Genji by Suematsu Kenchō (1855–1920), who lived in England from 1878 to 1886 as a secretary to the Japanese legation in London and a student of law and literature at the University of Cambridge.1 Clearly Suematsu’s underlying concern was political, an attempt to impress European nations with Japan’s social and cultural achievements, including the high position of women in the past.2 Suematsu stressed that “we [Japanese] had once made a remarkable progress in our own language quite independently of any foreign influence, and that when the native literature was at first founded, its language was identical with that [of the] spoken [language].”3 In many ways, his evaluation of The Tale of Genji (written in English, excerpts from which are included in this chapter) anticipated later Meiji views of the Genji.

In Japan, Tsubouchi Shōyō’s (1859–1935) The Essence of the Novel (Shōsetsu shinzui, 1885–1886) introduced a new concept of the novel that strongly influenced the development of critical discourse on literature in Japan. Achievement in fiction (shōsetsu), Shōyō argued, was an important indicator of a nation’s level of civilization, and he proposed a “reform of fiction” as part of an urgent national agenda to make Japan an “advanced,” “civilized” nation in the eyes of Western powers. Under the influence of Herbert Spencer’s social Darwinism, Shōyō traced the “development of fiction” from mythology through romance/fable/allegory to the novel and proclaimed that the most advanced “true novel” is the “realistic novel” (mosha shōsetsu), which depicts all aspects of “human feelings and social conditions” (ninjō setai) just as they are, unconstrained by didactic purposes.

On the one hand, Shōyō describes Genji as a representative romance of Japan (in the evolutionary lineage from mythology to romance to the novel). On the other hand, he considers Genji to be a “contemporary, social” novel, depicting the upper-class court society of its time, and an early Japanese predecessor of the modern realistic novel. The Tale of Genji appears prominently in the central section of Essence of the Novel, “The Main Purpose of the Novel” (Shōsetsu no shugan, excerpted here), in which Shōyō argues that the “true novel” depicts all aspects of life in contemporary society, particularly the innermost feelings of a variety of people. He clearly regards Genji as a masterpiece for its emotional content, realistic descriptions, and refined classical Japanese style. Shōyō also considers Genji’s literary language to be based on the actual colloquial language (zokugo) of the Heian court aristocracy. Genji thus came to be regarded as an early antecedent of the realistic and artistic modern novel that describes contemporary society in the vernacular language of the present.

In the 1890s, the first modern literary histories as well as the earliest modern anthologies of classical Japanese literature were published by graduates of the Japanese literature departments in the newly reconstituted Imperial University. All of them considered literature (bungaku) to be both a “reflection of the human mind/heart” and a “reflection of national life.” Accordingly, they illustrated, using concrete literary examples, the “development of the mentality of the nation” in order that “the nation’s people [could] deepen their love for the nation,” that “the national spirit” [could] be elevated, and that “social progress and development of the nation [could] be advanced.”4

Following the lead of Hippolyte Taine’s (1828–1893) History of English Literature (1864; English trans., 1872), Mikami Sanji (1865–1939) and Takatsu Kuwasaburō’s (1864–1921) two-volume History of Japanese Literature (Nihon bungakushi, 1890) characterized Japanese literature in terms of the Japanese national character. To them, the Chinese “value proper decorum”; the English are “calm and practical”; the French are “gallant and emotional”; and the Japanese “revere their gods” and are “loyal to their lords.” Since a nation’s literature reflects its people’s character, Chinese literature is “grand and heroic”; Western literatures, “precise, detailed, and exhaustive”; and Japanese literature, “elegant and graceful.”5 This belief persisted in subsequent literary historiography and had a lasting impact on Japanese views of their literature and national character, with The Tale of Genji as the foremost representative of Japan’s national literature.

Mikami and Takatsu’s discussion of Genji introduces its author, Murasaki Shikibu, as a virtuous woman and a talented writer; outlines the basic plot, with the Shining Genji and Lady Murasaki as the hero and the heroine; and lists the major commentaries and critical treatises. Kitamura Kigin’s Moonlit Lake Commentary, Andō Tameakira’s Seven Essays on Murasaki Shikibu, Motoori Norinaga’s The Tale of Genji: A Little Jeweled Comb, and Hagiwara Hiromichi’s A Critical Appraisal of Genji are recommended as four indispensable works for understanding Genji. Mikami and Takatsu disparage Buddhist and Confucian allegorical readings as slighting the rich intertextuality of Genji, a “predecessor of the realistic novel,” as well as praise its “exquisite,” “subtle,” and “precise” language; its “fertile imagination”; and its “careful design and compositional structure.” Echoing Hagiwara Hiromichi’s Critical Appraisal as well as Shōyō’s Essence of the Novel, Mikami and Takatsu reposition Genji and its earlier commentaries in the developing Meiji discourse on the novel and literature.

Japan’s national literature was defined in the context of two competing concepts of literature. On one hand was the Confucian idea of learning, which had been the traditional conception of literature in Japan, augmented by the Western idea of literature as humanities in general. On the other hand was the new, nineteenth-century European conception of imaginative literature defined primarily in terms of aesthetics: beauty, imagination, and moral elevation. As a result, the position of Genji, now defined as a novel, remained unstable until the early twentieth century. After the end of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, the field of literature rapidly became an independent cultural realm in which the specialized notion of aesthetic literature came to prevail, with the novel assuming a central position. In this context, The Tale of Genji came to be regarded as unquestionably the masterpiece of Japan’s national literature. Sassa Seisetsu’s (1872–1917) preface to A New Exegesis of The Tale of Genji (Shinshaku Genji monogatari, 1911–1914), translated here, exemplifies this view. Paradoxically, however, the institutional promotion of the new colloquial language and the aggressive separation of the new literary language from the old literary language led to a clear separation between “modern literature” and “classical literature,” making Genji the “greatest national classic,” written in a language that modern literary writers could no longer employ.

In this literary and cultural milieu, Yosano Akiko (1878–1942) published A New Translation of The Tale of Genji (Shin’yaku Genji monogatari, 1912–1913), the first complete modern colloquial translation of The Tale of Genji. Akiko had become established as a celebrated tanka (modern waka) poet and the leader of the Myōjō poetry coterie, and her tanka collection Tangled Hair (Midaregami, 1901) had a decisive impact on the aesthetic direction and popularity of the literary magazine Myōjō (1900–1908). But in the early twentieth century, both tanka and wabun-based prose were relegated to a secondary position by the rise of the colloquial novel as the central literary genre of the new age. From 1906 onward, although Akiko wrote a number of essays and short stories in the new colloquial style, it was her modern translation of Genji that allowed her to fully explore the new fictional form and language with the authority of a mediator between the (now feminized) classical language and the new colloquial language.

From its inception in the late 1880s, the notion of “national literature” in Japan, as in other modern nation-states, existed in a symbiotic relationship with “world literature.” Japanese scholars of classical literature stressed the value of The Tale of Genji as the “world’s earliest sophisticated, realistic novel” and as “required reading for everyone in the nation.” But even though the view that Japanese literature was ready to participate actively in world literature began steadily growing in the 1910s, it was not until the mid-1920s that The Tale of Genji suddenly became a fresh object of contemporary literary attention. This was the result of the publication between 1925 and 1933 of an English translation of Genji by Arthur Waley (1889–1966), as well as the international recognition accorded the work in the review by Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) of Waley’s first volume.

In 1922, the intellectual historian Watsuji Tetsurō (1889–1960) published three articles on Heian literature—The Pillow Book, mono no aware, and The Tale of Genji—in the newly established journal Shisō (Thought). In his article “On The Tale of Genji,” now considered a pioneering work of textual criticism, Watsuji suggests that Genji was not written in the current order of the chapters and that Murasaki Shikibu may have been only one of several authors of the text. In the latter part of this essay, Watsuji expresses his “long-held uncertainty with regard to the artistic value of The Tale of Genji.” “I hesitate to call it a masterpiece,” he complains; “it is monotonous, repetitive, and even its partially beautiful scenes are clouded by the dull tedium of the whole.”6

In 1926, Masamune Hakuchō (1879–1962) made a similar complaint in his essay “On Reading the Classics,” also translated here. Hakuchō found the style of the original Genji text to be “sluggish and loose” and “hard to read,” a style “that continues like a stream of jellyfish,” and “prevents us from being impressed by the truth of life.” From the mid-1920s, however, particularly after the first volume of Arthur Waley’s English translation was published, The Tale of Genji as “world literature” acquired new significance, and the novelist Tanizaki Jun’ichirō (1886–1965) praised the very stylistic characteristics that Watsuji Tetsurō and Masamune Hakuchō had criticized.

In his essay “On the Defects of the Modern Colloquial Written Style” (1929), Tanizaki argued that the modern colloquial style, which had developed since the middle of the Meiji period, was an artificial written language based on a “translation style” (hon’yakutai), a “half-breed” (konketsuji) of Japanese and Western languages, mixing Western syntax and new Chinese loanwords as substitutes for Western words, and that this hybrid had strangled the beauty and uniqueness of the Japanese language. This Westernized language, Tanizaki maintained, may be better suited for the clear, precise, and rational writings of science or philosophy, but not necessarily for literature, for which the original Japanese language had unique advantages.7 In his Manual of Style (Bunshō tokuhon, 1934), Tanizaki divides both classical and modern Japanese literature into two opposing types: the wabun-based style versus the kanbun-based style; the misty type versus the lucid type; the sluggish type versus the brisk type; the flowing, elegant type versus the solid type; the feminine type versus the masculine type; and the emotional type versus the rational type. These dichotomies, Tanizaki claimed, “could most simply be summed up as the Genji monogatari type versus the non–Genji monogatari type” and noted that while he, too, had been interested in the kanbun-based style in his younger years, he had become increasingly drawn to Genji’s wabun -based style.8 Beginning in the late 1920s, Tanizaki embarked on a series of stylistic and narratological experiments, during which he found in older Japanese literary styles fresh possibilities for exploring modernist fiction. In 1935, at the behest of the president of the Chūōkōron publishing company, Tanizaki began translating the entire Tale of Genji into modern Japanese, which was published between 1939 and 1941. His own account of the inception of his first translation and his working methods is translated in this chapter.

Beginning in the early 1930s, all primary- and secondary-school textbooks included selections from Genji, which was popularized through both these textbooks and modern colloquial translations. Several different modern translations appeared in this period, including Yosano Akiko’s revised translation (1938–1939).

In the postwar period, when the militaristic narratives associated with wartime Japan were removed from the school curricula, The Tale of Genji was recanonized as the cultural treasure of a new, nonmilitaristic, peaceful nation. Old translations were reprinted and new ones commissioned. As Japan rejoined the international community of nations in the 1950s, The Tale of Genji was held up as a cultural symbol for overseas consumption. For a middle-school textbook published in 1951, the leading Genji scholar Ikeda Kikan (1896–1956) wrote a brief biography of Murasaki Shikibu, in which he remarked:

This novel is said to be the oldest, the grandest, and the greatest novel in our country. It has been admired by many people in all times, and recently it has been translated into several foreign languages and has been praised throughout the world as one of the world classics.9

By the 1970s, Genji had been popularized through new adaptations, free translations, and new media (film, manga [comics], anime [animation]), all supported by a continuing tradition of Genji scholarship that has produced numerous new annotated editions, making it the most studied text in all of Japanese literature. Its continued importance as world literature, too, is attested by the appearance of several new foreign language translations, including two new (and complete) English translations, by Edward Seidensticker in 1976 and Royall Tyler in 2001. In addition, excerpts from Genji now are included in almost all English-language anthologies of world literature.

TOMI SUZUKI

Although it is not widely read or known today, Suematsu Kenchō’s (1855–1920) translation of the first seventeen chapters of The Tale of Genji, published in London in 1882 as Genji Monogatari: The Most Celebrated of the Classical Japanese Romances, was a literary sensation at the time. Extensively reviewed in important newspapers and magazines, it was also translated into German; partially rewritten in French; and reprinted, rewritten, or anthologized in English, in full or in part, no fewer than five times between 1882 and 1934.10 In an age when Europe and the United States were seized, as one observer wrote in 1881, by “the modern craze for things Japanese, which has converted grocer’s shops into Japanese art depositories, and flooded the country with penny fans and inferior porcelain,” it should come as no surprise that Suematsu’s translation attracted considerable attention.11

Suematsu lived in England from 1878 to 1886, and his introduction to Genji indicates that by 1882 he was thoroughly acquainted with Victorian views of literature.12 This is evident, above all, in his decision to market the work as a “classical romance” and a “true romance.” On the one hand, this reverberated with the contemporary distinction between “romances, or the stories of individual life, and chronicles, or stories of the nation’s life.”13 On the other hand, it also distanced Genji from the genre of “sensational romances” that then were so popular and so reviled.

Suematsu’s motivation for translating The Tale of Genji is unclear. On the eve of his departure for England, Suematsu had been instructed to study English and French historiography, so much of his own interest in the text must have been historical. At the same time, his political intentions become evident when he notes that readers “will be able to compare [classical Japan] with the condition of mediaeval and modern Europe.” Japan’s foreign minister, Inoue Kaoru (1836–1915), had arranged a series of meetings beginning in January 1882 between representatives of parties to the “unequal treaties.” As Suematsu hoped to see the treaties revised, the timing of the translation’s publication could not have been better.

MICHAEL EMMERICH

Genji Monogatari, the original of this translation, is one of the standard works of Japanese literature. It has been regarded for centuries as a national treasure. The title of the work is by no means unknown to those Europeans who take an interest in Japanese matters, for it is mentioned or alluded to in almost every European work relating to our country. It was written by a lady, who, from her writings, is considered one of the most talented women that Japan has ever produced….

Many Europeans, I daresay, have noticed on our lacquer work and other art objects, the representation of a lady seated at a writing-desk, with a pen held in her tiny fingers, gazing at the moon reflected in a lake. This lady is no other than our authoress….

In fact, there is no better history than her story, which so vividly illustrates the society of her time. True it is that she openly declares in one passage of her story that politics are not matters which women are supposed to understand; yet, when we carefully study her writings, we can scarcely fail to recognize her work as a partly political one. This fact becomes more vividly interesting when we consider that the unsatisfactory conditions of both the state and society soon brought about a grievous weakening of the Imperial authority, and opened wide the gate for the ascendency of the military class. This was followed by the systematic formation of feudalism, which, for some seven centuries, totally changed the face of Japan….

I may almost say that for several centuries Japan never recovered the ancient civilization which she had once attained and lost….

Another merit of the work consists in its having been written in pure classical Japanese; and here it may be mentioned that we had once made a remarkable progress in our own language quite independently of any foreign influence, and that when the native literature was at first founded, its language was identical with that spoken. Though the predominance of Chinese studies had arrested the progress of the native literature, it was still extant at the time, and even for some time after the date of our authoress. But with the ascendency of the military class, the neglect of all literature became for centuries universal. The little that has been preserved is an almost unreadable chaos of mixed Chinese and Japanese. Thus a gulf gradually opened between the spoken and the written language….

Again, the concise description of scenery, the elegance of which it is almost impossible to render with due force in another language, and the true and delicate touches of human nature which everywhere abound in the work, especially in the long dialogue in Chapter II, are almost marvellous when we consider the sex of the writer, and the early period when she wrote.

Yet this work affords fair ground for criticism. The thread of her story is often diffuse and somewhat disjointed, a fault probably due to the fact that she had more flights of imagination than power of equal and systematic condensation; she having been often carried away by that imagination from points where she ought to have rested. But, on the other hand, in most parts the dialogue is scanty, which might have been prolonged to considerable advantage, if it had been framed on models of modern composition. The work, also, is too voluminous.

In translating I have cut out several passages which appeared superfluous, though nothing has been added to the original…. The authoress has been by no means exact in following the order of dates, though this appears to have proceeded from her endeavor to complete each distinctive group of ideas in each particular chapter. In fact she had even left the chapters unnumbered…. It has no extraordinarily intricate plot like those which excite the readers of the sensational romances of the modern western style….

I notice these points beforehand in order to prepare the reader for the more salient faults of the work. On the whole my principal object is not so much to amuse my readers as to present them with a study of human nature, and to give them information on the history of the social and political condition of my native country nearly a thousand years ago. They will be able to compare it with the condition of mediæval and modern Europe.

(Shōsetsu shinzui)

The critic, playwright, and novelist Tsubouchi Shōyō (1859–1935) is perhaps best known for his translation of Shakespeare’s complete works into Japanese between 1884 and 1928. His Essence of the Novel is widely considered to be the first substantial work of literary criticism in Meiji Japan.14 Shōyō attended lectures in philosophy taught by American instructors at Tokyo University and was familiar with a variety of contemporary Western authors and critics. In his own writing, he attempted to integrate what he loved in traditional Japanese fiction with what he found worthy of emulation in Western literature, but he was rarely satisfied with the results. At the height of his career, frustrated with his own attempts to develop a literary language and style for the modern novel, he abandoned his efforts to succeed as a novelist.

Shōyō’s lifelong infatuation with traditional literature and his desire to imbue contemporary Japanese fiction with the finest qualities of Western literature are apparent in the references he makes to both The Tale of Genji and modern fictional prose in the following excerpts from his pioneering treatise on the novel.15 He devotes the first volume of The Essence of the Novel to a general discussion of “the art of the novel.” He combines examples from Western literature and history with those from China and Japan in an attempt to trace the development of prose from early chronicles and epics like the Iliad to didactic texts like Aesop’s Fables and the Zhuangzi.

In the second selection translated here, “The Main Purpose of the Novel,” he concludes that Genji can be used to illustrate his point that great prose fiction is about more than moral didacticism. In the third selection, Shōyō concludes that the novel is the most sophisticated form of prose fiction to arise from this tradition because it allows realism to trump didacticism. He argues that the novel is the literary form of the future and urges Japanese authors not to slavishly emulate the works of the Edo-period writers Kyokutei Bakin, Tamenaga Shunsui, and Ryūtei Tanehiko when they can follow the path of such great novelists as Sir Walter Scott, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Alexandre Dumas, and George Eliot.

PATRICK CADDEAU

Introduction

Our nation can boast of a most remarkable legacy in the composition of prose fiction [monogatari]. Looking to the distant past, we find The Tale of Genji, The Tale of Sagoromo, The Tale of Hamamatsu Chūnagon, and The Tale of Sumiyoshi. Later, one finds Ichijō Zenkō’s popular fiction followed by such works as Ono no O-Tsū’s The Tale of Jōruri in Twelve Episodes.16 Closer to our own era, we have [Ihara] Saikaku [1642–1693], Ejima Kiseki [1666–1735], Hiraga Gennai [1728–1780], and [Santō] Kyōden [1761–1816], all of whom wrote prose fiction and, in seeking ever greater repute in their own day, contributed to the increasing popularity of the novel [shōsetsu]. Talented writers of the day strove to compose historical romances [haishi]. Others sought to imitate the comedies of [Shikitei] Sanba [1776–1822] and [Jippensha] Ikku [1765–1831]. Others attempted to write love stories [ninjōbon] in the style of the famous Tamenaga Shunsui [1790–1843]. [Ryūtei] Tanehiko [1783–1842] became famous for An Imposter Murasaki and a Rustic Genji, and [Kyokutei] Bakin’s [1767–1848] reputation rests on his Satomi and the Eight Dogs [Hakkenden, 1814–1842]. But popular writers temporarily stopped publishing with the changes wrought by the Meiji Restoration, leading to a decline in the novel’s popularity. Today the situation has greatly improved, and writers now seem to be publishing prose fiction again…. While there is no shortage of so-called writers of popular fiction, nearly all of them should really be considered as producing adaptations, for not a single one is worthy of the title of author…. This is most unfortunate…. For this reason, I offer my own views concerning the reform and improvement of the novel in our country in an attempt to educate readers while also enlightening authors. It is my hope that in my doing so, we will see the prose fiction of our nation surpass the European novel so that it takes its rightful place among the arts of painting, music, and poetry.

The Main Purpose of the Novel

In A Little Jeweled Comb, Motoori Norinaga argues as follows concerning the main purpose of The Tale of Genji:

From olden times, there have been various interpretations of the intentions of this tale. All of them, however, fail to take into account the nature of those works that we call tales. They argue entirely in the idiom of Confucian and Buddhist texts, which was not what the author intended. Although there happen to be points of chance resemblance and accord with Confucian and Buddhist texts, it will not do to seize on these as characterizing the work as a whole. Its overall import differs sharply from works of that sort. Tales possess a nature uniquely their own.

The preceding quotation from Motoori Norinaga clearly explains the main purpose of the novel. His is truly a work that addresses the nature of prose fiction. I understand that many lesser scholars of classical literature have mistakenly lectured on such far-fetched topics as the notion that Genji is in fact a work of didactic intent. How terribly mistaken they are.

In the second volume, Shōyō talks about specific techniques and principles relating to the composition of prose fiction. In discussing literary style, he refers to Genji as the finest example of the classical Japanese language and praises Murasaki Shikibu’s style for its ability to evoke the culture of her time. In the section “Compositional Techniques of the Novel,” he returns to Genji for an example of ideal structure and composition. He begins by arguing that when considering the design of the novel, it is best to avoid the monotony of a single compositional approach. For example, humor should be complemented by sadness. Likewise, tragic novels will bore the reader if they contain nothing but tragedy. It is particularly important that the conclusion be written in a simple and understated style.

Compositional Techniques of the Novel

Murasaki Shikibu, in hinting to the reader of Genji’s passing simply by creating the chapter [title] “Kumogakure,” displays her true genius as a great writer.

[“CONSTRUCTING A MAIN CHARACTER”]

The “main character” [shujinkō] is the character who is the focus of the novel, what might be called its “main object of worship.”…Without a main character, it [Genji] probably would lack logical continuity.

There are two schools of thought regarding construction of a main character: the realist approach and the idealist approach. The main difference is that the realists take as their model people as they exist, while the idealists take as the basis for a character what society says ought to exist. Take, for example, Hikaru Genji in The Tale of Genji. In Murasaki Shikibu’s time, there must have been many men of a rank similar to Genji’s who were like him. For this reason, ignorant men among the scholars of classical literature have argued that Genji is an allegorical work in which each man and woman represents someone who was alive at that time. Nothing could be further from the truth. They simply have failed to recognize that Murasaki Shikibu was a writer belonging to the realist school.

TRANSLATED BY PATRICK CADDEAU

(Shinshaku Genji monogatari)

One of the many consequences of the rise in literacy during the Pax Tokugawa was the attempt to wrest the riches of Heian literature—and particularly The Tale of Genji—from the control of their aristocratic custodians and make them available to a burgeoning national readership. As we saw in chapter 7, the task was begun by Edo-period scholars of national learning, who compiled a number of commentaries based less on aristocratic familial traditions than on the model of Chinese “critical philology” (kōshōgaku). Far more effective as means of bringing Heian-period texts into the public domain, however, were the commercial publication of printed editions and vernacular translations. The first complete translation of a classical text into modern Japanese was the vernacular version of Tales of Ise in seventeenth-century Japanese: Tales of Ise in Plain Language (Ise monogatari hirakotoba, 1678). By the end of the eighteenth century, two complete translations of the Kokinshū, one by Motoori Norinaga and the other by Ozaki Masayoshi (1755–1827), had been completed and published. Despite their colloquial character, the purpose of these translations was explicitly didactic: to enable the beginning student to experience the courtly language of antiquity as “a part of his own being.”17 At this stage, translations did not replace commentaries; rather, they supplemented them.

Bibliographies reveal that during the Edo period, more than a dozen attempts were made to render Genji into the contemporary vernacular.18 None were ever published complete, and the only Meiji-period attempt to produce one was terminated after two volumes. This was A New Exegesis of The Tale of Genji (Shinshaku Genji monogatari, 1911–1914). The first volume contained the eight chapters from “Kiritsubo” to “Hana no en,” and the second volume included another six chapters, bringing the work up to the end of “Miotsukushi.”

A New Exegesis provides an edition of Genji with headnotes similar in format to those in Kitamura Kigin’s Moonlit Lake Commentary (Kogetsushō, 1673). The compilers also included summaries of each chapter, as well as separate sections of commentary and a modern Japanese translation. Each section of translation is preceded by the original text and followed by commentary. In Shinshaku Genji monogatari, translation performs essentially the same function as commentary: it is to be read as an adjunct to and not as a substitute for the original text.

The four compilers of Shinshaku Genji monogatari were students at the Imperial (Tokyo) University between 1890 and 1900: Fujii Shiei (1868–1945), Sassa Seisetsu (1872–1917), and Nunami Keion (1877–1927) graduated from the Department of National Literature; and Sasakawa Rinpū (1870–1949), from the Department of National History. All went on to earn their living teaching Japanese literature at high schools and universities. All were also haikai (popular linked verse) poets, and members of the Tsukubakai poetry society founded by Imperial University students in 1894. An understanding of Genji had always been a prerequisite of haikai composition, and the fact that the compilers of A New Exegesis chose to list themselves by their haikai pen names suggests that they still saw themselves as part of the “old” world of haikai as well as the new world of literature in the service of the nation.

In a grandiloquent preface to the initial volume, Sassa Seisetsu explained the mission that underlay the translation project and, in doing so, articulated the agenda of virtually his entire generation of national literature scholars.19 His mantra-like repetition of the term mono no aware (emotional sensitivity) to encapsulate the Japanese “national character” is noteworthy. Clearly, he wanted to mitigate the image of Japan as a nation of battle-hungry samurai driven by the code of the warrior (bushido). In arguing for the preeminence of the culture delineated in and exemplified by The Tale of Genji, Sassa and his colleagues were attempting to resituate Japan in the world.

G. G. ROWLEY

Whether or not they know the characters with which the words are written, no one with even the slightest knowledge cannot call to mind the title of The Tale of Genji. Yet most have only a vague sense that it is the greatest treasure of our national literature. They know not one thing about its style, its structure, or the thought that informs it. Many have read through two or three passages or a chapter or two in a “history of national literature” or a “national language reader” and admired the fluid style. Many have become familiar with the general structure of the plot through Shinobugusa [A Reminder (of The Tale of Genji)] or Osana Genji [A Child’s Genji] or another of the various digests or adaptations.20 But when it comes to people who have read it through from beginning to end, even if one searched among the ranks of those who lecture on contemporary literature, one would not find one person in one thousand one hundred. Indeed, we have no hesitation in asserting that even among specialists in language and literature, most have only read as far as [the twelfth chapter] “Suma.” Why is it, then, that the name of The Tale of Genji is bandied about so noisily when so few have actually read it? Probably because, first, people have been troubled by the difficulty of understanding its words and phrasing and, second, it is dismissed as a mere curiosity and people do not realize that it is a book that everyone in the nation should read.

Our first task in this Shinshaku, therefore, was to make The Tale of Genji accessible and popular, and thus we have translated it into ordinary spoken language. The purpose of this book is simply to make Genji accessible. Accordingly, for those planning a more traditional study of the tale, this book, from the very outset, will not be the best. Conversely, as a Japanese, if you will be satisfied acquiring some sense of what Genji is and acquainting yourself with the rudiments of its style, its structure, and the thought that informs it, then this simple Shinshaku will probably serve you well. Our project, if it is not too much to hope for, is to make the incomprehensible Genji a thing of the past, once and for all. If at that point, readers still do not flock to Genji, then it can only be that they do not fully appreciate its worth, that they do not fully understand why it is a book that everyone in the nation should read. Anyone who attempts to make Genji easily understandable, therefore, has a duty to explain its true worth.

To begin with, Genji is the unrivaled treasure of the nation and, as such, is something we can boast about to the entire world. When we listen to what the people are saying at the present time, they are praising bushido; all the nations of the world together marvel at our bushido. Yet even many native Japanese forget that the beautiful bushido of the Kamakura period onward was rooted in the Heian court, with its culture of the purest refinement and sensibility. The concepts of firm will and devotion to duty were the strong points of bushido. Just as significant, however, was the graceful, elegant, and genial taste of the Heian court, without which our warriors would have amounted to no more than brutes from the north. If in an earlier age there had been no Kokinshū, no Tales of Ise, no Tale of Genji; if in the age of military government there had been no poetry and no linked verse; [and] if military men had never cultivated mono no aware, they would have been only heartless warriors, mere battle-loving barbarians.

Leaving aside for the moment the distant age of the gods, it is undeniable that after the heavenly ancestors of our race subjugated the central regions of the country, the culture that at long last flowered was nourished by the literature and art of Korea, China, and India. No matter how much superb art and literature survive today from the Asuka, Fujiwara, and Nara courts, the period up to and including Nara must be regarded as an era of importing culture from abroad, when literature, art, religion, and other elements from the outside had not been fully assimilated to our own literature and art. For that reason, the poems of the Man’yōshū are no more than the simple cries of joy and anger common to all primitive peoples. Two hundred years into the Heian period—what with the vogue for Chinese poetry, the diffusion of exoteric and esoteric Buddhism, and the rise of the purely Japanese in literature and art—imported literature, art, and religion were completely assimilated into and fused with native thought. In the natural development of our national character, this imported culture was fully absorbed and digested, whereupon the unique literature and art of our own nation came into full bloom along with the efflorescent glory of the Fujiwara clan. In the full maturity of peace, the most important accomplishments of ladies and gentlemen were poetry and music. Striving single-mindedly for refinement of sensibility and a richer appreciation of beauty, mono no aware was the foremost aesthetic, the highest moral; everything that a person did was always judged by this standard. Is this not the culture of the Heian court?

According to what we hear, Rome should be regarded as the epitome of a culture based on reason, whereas the culture of Greece is a culture of beauty and feeling. This, however, is no more than a comparative evaluation. When in the world, where in the world, has there been a culture like that of our Heian court, so utterly ruled by sensibility? Where in the world were the moon and the cherry blossoms so admired? In what period was there such fondness for mono no aware? The world misunderstands our bushido; they say that we are a war-loving people. Yet what is unique in the culture of our nation is this emotionalism, this love of beauty. In our opinion, the most refined culture in the world is the culture of our own Heian court, and our Tale of Genji is truly the epitome of this culture. Nonetheless, it must be said that the so-called bushido of the Kamakura period and later was sullied with the bloody dust of battles, and to a certain degree this hindered the development of a natural and harmonious national character. Be that as it may, those investigating our true national character must first of all look back to the Heian court and The Tale of Genji.

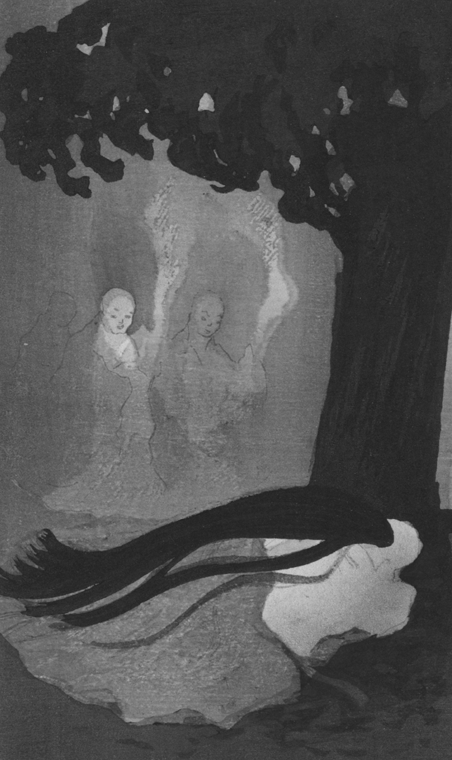

So refined indeed were their sensibilities that they were uninterested in tales of the weird or the supernatural. The ghosts and the living spirits of Genji are, almost without exception, paler than those of the superstitions of our own day. This vast work in fifty-four chapters never depends on strange and terrifying turns of plot to capture the reader’s curiosity. Simply by setting down the things she observed, day and night, in the society of her own time, the author makes it impossible for the reader to set the work aside, a rare and extraordinary skill. When you note the period in which the work was composed, around the Kankō era [1004–1012], during the reign of the Ichijō Emperor, this turns out to be more than three hundred years and several decades before the age when Chaucer, whom Tsubouchi Shōyō called the English Murasaki Shikibu, first laid the foundations of English literature. Apart from the ancient literatures of Greece and Rome in the West and India and China in the East, this is a time when nowhere else in the world is any literature worthy of attention to be found. Indeed, in the Kankō era, which corresponds to the beginning of the eleventh century, not a single realistic tale [shajitsu monogatari] or novel depicting human emotion [ninjō shōsetsu] is to be found, in either the East or the West. The Tale of Genji, therefore, is not only the unrivaled treasure of Japanese literature; it should in fact be called an unrivaled treasure of world literature.

Given, then, that The Tale of Genji represents the very best in our national character, is the unrivaled treasure of our national literature, and, moreover, is an unrivaled treasure of world literature, how is it that we, the people of Japan, ignore it? Particularly since over the ages the scholars of our nation have made it the focal point of so much research and not a single work of our earlier literature has escaped its influence?

Even before it had been completed, The Tale of Genji was the talk of the court, and before long, men and women in both the city and the provinces were vying with one another to make copies of it. The earlier tales came to seem no brighter than stars before the moon. Countless authors of tales competed to produce adaptations and variations. Nor were poets and masters of linked verse behindhand in drawing on the landscape of Genji as poetic material. Later, with the development of the study that we now call poetics [kagaku], the most revered books after the Kokinshū were Tales of Ise and Genji. Every initiate in the traditions of the way of poetry known as the “secret teachings of the Kokinshū” [Kokin denju] was constantly engaged in the study of this tale. Accordingly, we find no other tale in our literature that has inspired more works of commentary and criticism than this one. To enumerate only the best known of these: from the Kamakura and Muromachi periods are the Suigenshō,21 Shigenshō,22 Sengenshō, Kakaishō, Kachō yosei, Rōkashō, Rin’itsushō, Sairyūshō, Myōjōshō, Mōshinshō;23 at the beginning of the Edo period came the Mingō nisso and the Kogetsushō;24 [and] following the revival of the study of the classics were Genchū shūi, Shijo shichiron, Tama no ogoto, and Genji monogatari hyōshaku.25 Never for a moment did scholars, whether of traditional poetics or the new national learning, neglect the intensive study of Genji. Consequently, the vocabulary, the sources, the thought, and the structure of Genji exerted a ceaseless influence on their works. No matter what the endeavor, it is wasted effort for anyone who wishes to read Japanese prose, Japanese poetry, linked verse, and the like not to recognize Genji as the wellspring of them all.

And not just Japanese prose and poetry: as is well known, there are many Genji plays in the repertoire of that progenitor of our drama, the nō. Even among the popular songs of the age of the Northern and Southern Courts, an important source for nō drama, many derive from Genji. Furthermore, as a result of the masters of linked verse immersing themselves in Genji, its influence is plainly to be seen not only in linked verse proper but also in haikai. Thus from early Edo onward, the Teitoku school made Genji required reading, along with the Kokinshū and the Tales of Ise. Likewise, Kitamura Kigin, himself a poet of the Teitoku school, wrote a commentary on Genji, the Kogetsushō, and various haikai poets and literati such as Hinaya [Ryūho]26 and Kitamura Koshun wrote a number of digests and popularizations such as Osana Genji, Jūjō Genji [A Genji in Ten Volumes], Shinobugusa, Hinazuru Genji [A Fledgling’s Tale of Genji], and Wakakusa Genji [A Young Sprout’s Tale of Genji].27

It must have been at about this point that early modern writers of popular literature, even if they knew nothing about the original text, caught something about the general idea of Genji from either nō or digests and popularizations. Saikaku structured his Life of an Amorous Man [1682] as a story of a single man who has relations with numerous women. Chikamatsu’s Kokiden uwanariuchi brings together the Kokiden Empress Mother and the Rokujō Consort.28 There is a song, with koto accompaniment, about Oborozukiyo, and in the theater, Lady Aoi’s vengeful spirit is portrayed. Then, after the resurgence of ancient studies [kogaku], when the literature of the past became somewhat better known, an adaptation of the entire tale appeared: An Imposter Murasaki and a Rustic Genji.29 In the Bunka [1804–1818] and Tenpō [1830–1844] eras, this work was received with unprecedented acclaim. Such was its vogue that nothing—from color prints and drama to clothing and household furnishings—was untouched by it. This is but another example of the extraordinary influence of Genji itself.

An Imposter Murasaki and a Rustic Genji and its ilk are extraordinarily crude adaptations, which, needless to say, show a complete disregard for the sensibility of the original text. Even judged as one of Tanehiko’s popular fictions, it is not a work of the first order. The only reason that it drew such praise, it seems to me, is that knowledge of our Tale of Genji, however vague, had, through the several literary arts, spread throughout society from top to bottom, and this in itself inspired boundless admiration for the work.

Ah! The Tale of Genji! Were we to lose it, the literary arts of the Heian court would lose most of their luster. Were we to banish its influence, we would lose half of all the literary arts since the Kamakura period. And this is but the prospect in the field of literary history. How immense would be the loss were we to dismiss it as a source for painting and the plastic arts. Ah! It is not simply as a major work of literature from the past that The Tale of Genji is the unrivaled treasure of the nation. For some eight hundred years, it has never ceased to exert a profound and widespread influence on our literature and arts while at the same time it has provided an unshakable basis for the sensibility and the thought of the people of our nation.

With our work on the Shinshaku—though in many ways we have not fulfilled our expectations—it is our earnest hope that we may bring a bit of clarity to our readers’ vague knowledge of this tale. It is our earnest hope that we may give our fellow citizens an opportunity to reflect anew upon our national character.

TRANSLATED BY G. G. ROWLEY

(Shin’yaku Genji monogatari no nochi ni)

By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, the descendants of Edo-period scholars of national learning were calling for a modern translation of The Tale of Genji that would help build a national identity both at home and abroad. The respect accorded novels in Europe also contributed to this perception: in Genji, it was felt, Japan had something comparable. To this end, Yosano Akiko (1878–1942) took a major step in 1912 to 1913 when she published her first translation of Genji into colloquial Japanese, Shin’yaku Genji monogatari (A New Translation of The Tale of Genji).

Yosano Akiko was born into a merchant-class family in the old port city of Sakai on the Inland Sea south of Osaka. She received a comparatively good education for a young woman of her class and time, completing primary school and going on to graduate from the Sakai Girls’ School in 1892. The Tale of Genji was her favorite book: she once wrote that she could not count how many times she had read Genji before she turned twenty.30 Romantic yearning became reality when in June 1901 she ran away from home to live with her lover, the poet Yosano Hiroshi (pen name Tekkan, 1873–1935), in Tokyo. In August of that year, her literary career was launched with the publication of Midaregami (Tangled Hair), a collection of 399 tanka that has remained her most celebrated work.

It is clear from the afterword to her first modern translation of The Tale of Genji that Akiko regarded Genji as a novel (shōsetsu) and Murasaki Shikibu as a novelist (shōsetsuka). Therefore, she had no compunctions about translating the language of the Heian-period “novel” into the novelist’s language of her own time.31 With her publisher, Kanao Tanejirō (1879–1947), Akiko originally planned a thousand-page translation that would be divided evenly into three volumes. At first she cut boldly, drastically rewriting the twenty-one chapters from “Kiritsubo” to “Otome.” But readers wrote to say that they wanted a more complete translation. She complied, and the later chapters were translated more thoroughly—though by no means in their entirety—necessitating a fourth volume.32 By reducing the length of the tale and translating freely, Akiko rewrote Genji in the language of the modern novel. She thus broke completely with an exegetical tradition grounded in the study of the Chinese classics and developed by generations of scholars for the interpretation of works in the native literary tradition. The Shin’yaku was designed to be read from cover to cover, not pored over piecemeal as a commentary would be. Although Akiko was quick to disparage her first translation, it was hailed as a landmark by Ueda Bin (1874–1916) and Mori Ōgai (1862–1922) and reviewed favorably by the major newspapers and literary journals of the period. It also was popular with readers and remained in print for twenty-five years until her second translation began to appear in October 1938.

G. G. ROWLEY

[…] Of all the classics [koten] of our country, The Tale of Genji is the book I have most loved to read. Quite frankly, when it comes to comprehending this novel [shōsetsu] in all its complexity, I have the stubborn confidence of a master.

My approach to translating this work has been much like that of beginning painters, who, in emulating the masterpieces of earlier ages, may produce rather free renditions of them. I have eliminated those details that, being far removed from modern life, we can neither identify nor sympathize with and thus only resent for their needless nicety. My principal aim has been to re-create as directly as possible the spirit of the original through the instrument of the modern language. I have endeavored to be both scrupulous and bold. I did not always adhere to the original author’s expressions; [that is,] I did not always translate literally. Having made the spirit of the original my own, I then attempted a free translation.

Needless to say, I do not hold in high regard any of the existing commentaries on The Tale of Genji. The Moonlit Lake Commentary, in particular, I find to be a careless work that misinterprets the original.

For the first few chapters, from “Kiritsubo” onward, I have attempted a somewhat abbreviated translation. Since these chapters have long been widely read and offer few difficulties, I thought that little more was needed. Beginning with the second volume of this work, however, for the benefit of those who might find it difficult to read the original, I’ve taken care to translate the text virtually in its entirety.

The Tale of Genji can be divided into two large parts: the part in which Hikaru and Murasaki are the main characters, and the part in which Kaoru and Ukifune are the main characters. When we reach the ten Uji chapters in the second part, the sumptuous style of the first part, replete with glitter and refinement, gives way to a simpler and cleaner style, which imparts an air of freshness to the narrative. This sense of rejuvenation is the product of Murasaki Shikibu’s genius, ever vigorous, at which one can only marvel. [Accordingly,] those who fail to finish the final ten Uji chapters when reading The Tale of Genji cannot be said to have read the whole of Murasaki Shikibu.

None of the principal characters in The Tale of Genji, neither men nor women, is given a name. Therefore, past readers have borrowed words from poems with which the characters are associated, using them as nicknames. For the sake of convenience, I have followed these customary appellations in this work….

In conclusion, to commemorate this occasion, I wish to add that in the summer of last year, in Paris, I personally presented copies of the first two volumes of this work to the sculptor Auguste Rodin and the poet Henri de Régnier.33 Rodin looked through the illustrations and, exclaiming all the while over the beauty of the Japanese woodblock prints, he said:

The number of people in France and in Japan studying the language and thought of our two countries will gradually increase. I bitterly regret being unable to read Japanese, but I trust that one day in the future I shall be able to appreciate the thought of this book by means of a friend’s translation.

The memory of his words is still fresh in my mind.34

TRANSLATED BY G. G. ROWLEY

(Shin-shin’yaku Genji monogatari)

YOSANO AKIKO

Akiko was never happy with her first, abbreviated, translation of The Tale of Genji and always hoped to prepare a complete version. In the autumn of 1932, aged fifty-four, she began work; Shin-shin’yaku Genji monogatari (A New New Translation of The Tale of Genji) was published in six volumes between October 1938 and September 1939. It does not seem to have attracted the notice that had greeted the publication of Shin’yaku a quarter of a century earlier and, by all accounts, was a commercial failure. By 1938, Japan was at war. Moreover, Akiko’s translation had a powerful competitor in Tanizaki Jun’ichirō’s first modern translation of Genji, which began appearing in January 1939. Akiko’s publisher, Kanao, could not afford to advertise extensively, and some people apparently thought that Shin-shin’yaku was merely a reprint of the earlier Shin’yaku. Only after the end of World War II was Shin-shin’yaku commercially successful. It was first reprinted as part of the Nihon no Bunko (Library of Japan) series during the Occupation—before the appearance of Tanizaki’s second translation—and has since been republished several dozen times in a variety of formats.35

Akiko’s “Afterword” to Shin-shin’yaku is a useful summary of her views on the structure and authorship of Genji.36 In both these areas of research, Akiko was recognized by twentieth-century scholars as an important pioneer.37

G. G. ROWLEY

[…] I believe that The Tale of Genji is a work in two parts by two authors. I am unable, however, to set forth in detail my research on the matter here. It has long been said that the ten Uji chapters are the work of Murasaki Shikibu’s daughter Daini no Sanmi.38 Many Tokugawa-period scholars of national learning denied this. Previously, I too was so persuaded. In the Meiji period, when Dr. Kume Kunitake wrote in a nō journal that Genji appears to have been written by several people, I did not at all accept this, thinking that although Dr. Kume was a first-rate scholar of history, he was no scholar of literature.39 It was some years before I began work on the Shin-shin’yaku that I realized that there were two authors of Genji. The work of the first author ends at “Fuji no uraba”: everything is very auspicious, and after Genji becomes Honorary Emperor in Retirement [daijō tennō] all is tinted in gold. Undaunted, the second author begins to write about Genji facing a turn in his fortunes. The woman he loved best, Lady Murasaki, dies, and there also is Nyosan no Miya’s [Onnasannomiya’s] indiscretion. In preparation for the birth of Kaoru, the main character of the latter part, talk suddenly turns to the women of the court after the Suzaku Emperor retires. Suzaku’s pathetic fondness for Nyosan no Miya prepares the way for Kaoru’s bounty. The skill with which the novel is structured here surpasses that of the first part.

If one reads the original with care, one should notice that from the “Wakana” chapters onward, the text is constructed differently. What had without fail been kandachime, tenjōbito [senior nobles and privy gentlemen] becomes shodayū, tenjōbito, kandachime [stewards, privy gentlemen, and senior nobles].40 This should be immediately apparent to those who read a recent movable-type edition rather than an old manuscript or woodblock-printed edition. The style is bad; there are fewer poems. And superior poems are exceedingly rare. The first part, written by Murasaki Shikibu, abounds in superb poems—not that there are none whatsoever by the second author.

me ni chikaku utsureba kawaru yo no naka o / yukusue tōku tanomikeru ka na

Ah, how trustingly I believed that what we had would last on and on,

when your feelings in this world shift and change before my eyes.41

obotsu ka na tare ni towamashi ika ni shite / hajime mo hate mo shiranu wagami zo

What can it all mean, and whom have I to question? What is my secret,

when I myself do not know whence I come or where I go?42

These poems closely resemble the first poem in the autumn section of the Goshūishū [1086] by Daini no Sanmi:

haruka naru Morokoshi made mo yuku mono wa / aki no nezame no kokoro narikeri

In the autumn, waking from sleep and opening one’s eyes—that feeling

is like traveling all the way to far distant Cathay.43

This poem is very similar, is it not?

At the beginning of the “Takekawa” chapter, which is couched as a tale told by an elderly serving woman who had worked in the household of the late chancellor [Higekuro], it is written: Murasaki no yukari koyonaki ni wa nizameredo. This passage means “What follows will not be of the same quality as the foregoing written by Murasaki Shikibu,” and it is wrong of commentators to interpret this passage as referring to Lady Murasaki in the novel.44 It would be strange, would it not, to compare Lady Murasaki, who had no descendants, with those of a different household?

Previously, when I was doing this research, I calculated twenty-six years as the period between the writing of the first part [of Genji] and the writing of the latter part.45 By then, the era of the Heian court had given way to an era in which provincial administrators using military force were beginning to gain power. One of these is the rich man who, having been governor of Michinoku, becomes the deputy governor of Hitachi.46

It still is possible to see a plaque in the hand of Emperor GoReizei [1025–1068; r. 1045–1068] in the temple next door to the Byōdō-in [in Uji]. Kanbun diaries kept by men of the period say that when GoReizei was crown prince [1037–1045], he often went to visit the mansion of [Fujiwara no] Yorimichi in Uji. Daini no Sanmi was Emperor GoReizei’s wet nurse; she went often to Uji in his entourage and came to know the place well.47

The poems [in this part] are not as good as those of the author of the first part, but neither are they mediocre. Because this is a great novel from the hand of one who had distinguished herself as a poet at that time, I searched high and low for Daini no Sanmi’s personal poetry collection, but it is no longer extant.48 I carefully examined the Daini Collection [Daini shū], which is listed in the catalog of the Kōgakukan in Ise, but it is the work of Sanmi’s daughter, the woman known [also] as Sanmi who served GoReizei’s consort, and the compositions are far inferior to her mother’s poems, let alone her grandmother’s.

Ukifune already is a subject of discussion in the Sarashina Diary [Sarashina nikki], but because the diary, which begins with an account of the author’s younger days, was written in her later years, it is possible that her memory is not entirely reliable. Although in my estimate of twenty-six years I took into account the year in which the Sarashina diarist returned to the capital, it may be that this gap is a little too long.49

The author whose style and narrative technique in the “Wakana” chapters are rough has become a splendid writer by the “Kashiwagi” and “Yūgiri” [chapters]. I say this because these chapters so abound in genius. From the “Azumaya” chapter on, her technique, as much as the content, is magnificent. The author of the first part, Murasaki Shikibu, was extraordinary as a novelist [shōsetsu sakka] and as a poet [kajin]; Daini no Sanmi, who wrote the second part, was, in my opinion, a great general practitioner of literature [bungakusha]. It is a shame that I do not have the time to expound this in greater detail….

TRANSLATED BY G. G. ROWLEY

Arthur Waley’s (1889–1966) translation of Genji monogatari was published in six volumes from 1925 to 1933. Although this translation was completed nearly half a century after the publication of a partial translation by the Japanese diplomat and journalist Suematsu Kenchō, Waley’s work is often considered the first English translation of Murasaki Shikibu’s tale. It was through Waley’s translation that The Tale of Genji came to be recognized inside and outside Japan as a literary masterpiece with the potential of rivaling the great modern European novels. It was indeed the new understanding of this work as a “novel” that guided modern Japanese writers like Masamune Hakuchō and Tanizaki Jun’ichirō in their encounters with this work and led Jorge Luis Borges to call it a “psychological novel” in his review, published in 1938.50

A graduate of King’s College, Cambridge, Waley began studying Chinese and Japanese while working in the Print Room of the British Museum, where he was appointed manager of the China and Japan collection. Waley began publishing translations of Chinese and Japanese poems in the late 1910s, and by the time he started to work on Genji, he had already published two books on Japanese literature: Japanese Poetry: The Uta (1919) and The Nō Plays of Japan (1921). Waley’s introduction of the eleventh century Japanese tale (based on the Hakubunkan edition of 1914) caused a stir in the English-speaking literary world, and the volumes were enthusiastically reviewed in leading literary journals such as the Times Literary Supplement and The Nation. Waley’s translation was subsequently retranslated into many European languages, including Italian, German, Dutch, Swedish, and French.

Waley’s liberal approach to translation is revealed in this reflection in 1958: “When translating prose dialogue one ought to make the characters say things that people talking English could conceivably say. One ought to hear them talking, just as a novelist hears his characters talk.”51 In the introduction to the first volume of the translation of Genji monogatari, Waley makes the author and text familiar to the reader by referring to contemporary British society:

There is a type of disappointed undergraduate, who believes that all his social and academic failures are due to his being, let us say, at Magdalene instead of St. John’s. Murasaki, in like manner, had persuaded herself that all would have gone well if her father had placed her in the highly cultivated and easy-mannered entourage of the Emperor’s aunt, Princess Senshi.52

Waley’s equation of Murasaki Shikibu with a male university student at a prestigious British institution provides an interesting juxtaposition to the review of his translation of Genji by Virginia Woolf (1882–1941), for whom women’s exclusion from higher education was a crucial part of her feminist thinking. Soon after the publication of a book-length collection of essays, The Common Reader (1925), and her fourth novel, Mrs. Dalloway (1925), Woolf, who was an established literary critic and an emerging highbrow writer at the time, received an assignment from the British edition of Vogue to review the first volume of Waley’s translation.53 From the beginning of her career as a published writer and throughout the 1920s, Woolf’s main source of income was literary journalism, primarily reviews of contemporary works. She was a regular reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement and other major literary journals, and it was largely for financial reasons that she wrote for the commercial magazine Vogue, to which she contributed a total of five signed articles in the 1920s.54

Drawing from Murasaki’s own vision of the artist, Woolf characterizes the world of Genji as one of beauty, serenity, spontaneity, and perfection, in contrast to which the contemporary Western world appears crude and sordid, despite possessing richness, vigor, and maturity that eclipse this ancient Japanese work. Nonetheless, the evocative metaphor of Murasaki’s poetry “break[ing] the surface of silence with silver fins” echoes Woolf’s own artistic vision, which can be traced throughout her writings, and suggests that The Tale of Genji offered Woolf an inspiration for an ideal type of art that she was trying to create. While Woolf did not include Murasaki Shikibu among the “great storytellers of the Western world” (gendered as masculine), she later named her as one of the world’s three great women writers in her feminist treatise A Room of One’s Own (1929), thereby inducting the Japanese author into the canon of women’s writing.

HITOMI YOSHIO

Our readers will scarcely need to be reminded that it was about the year 991 that Ælfric composed his Homilies, that his treatises upon the Old and New Testament were slightly later in date, and that both works precede that profound, if obscure, convulsion which set Swegen of Denmark upon the throne of England. Perpetually fighting, now men, now swine, now thickets and swamps, it was with fists swollen with toil, minds contracted by danger, eyes stung with smoke and feet that were cold among the rushes that our ancestors applied themselves to the pen, transcribed, translated and chronicled, or burst rudely, and hoarsely into crude spasms of song.

Sumer is icumen in,

Lhude sing cuccu

—such is their sudden harsh cry. Meanwhile, at the same moment, on the other side of the globe the Lady Murasaki was looking out into her garden, and noticing how “among the leaves were white flowers with petals half unfolded like the lips of people smiling at their own thoughts.”

While the Ælfrics and the Ælfreds croaked and coughed in England, this court lady, about whom we know nothing, for Mr. Waley artfully withholds all information until the six volumes of her novel are before us, was sitting down in her silk dress and trousers with pictures before her and the sound of poetry in her ears, with flowers in her garden and nightingales in the trees, with all day to talk in and all night to dance in—she was sitting down about the year 1000 to tell the story of the life and adventures of Prince Genji. But we must hasten to correct the impression that the Lady Murasaki was in any sense a chronicler. Since her book was read aloud, we may imagine an audience; but her listeners must have been astute, subtle minded, sophisticated men and women. They were grown-up people, who needed no feats of strength to rivet their attention; no catastrophe to surprise them. They were absorbed, on the contrary, in the contemplation of man’s nature; how passionately he desires things that are denied; how his longing for a life of tender intimacy is always thwarted; how the grotesque and the fantastic excite him beyond the simple and straightforward; how beautiful the falling snow is, and how, as he watches it, he longs more than ever for someone to share his solitary joy.

The Lady Murasaki lived, indeed, in one of those seasons which are most propitious for the artist, and, in particular, for an artist of her own sex. The accent of life did not fall upon war; the interests of men did not centre upon politics. Relieved from the violent pressure of these two forces, life expressed itself chiefly in the intricacies of behaviour, in what men said and what women did not quite say, in poems that break the surface of silence with silver fins, in dance and painting, and in that love of the wildness of nature which only comes when people feel themselves perfectly secure. In such an age as this Lady Murasaki, with her hatred of bombast, her humour, her common sense, her passion for the contrasts and curiosities of human nature, for old houses mouldering away among the weeds and the winds, and wild landscapes, and the sound of water falling, and mallets beating, and wild geese screaming, and the red noses of princesses, for beauty indeed, and that incongruity which makes beauty still more beautiful, could bring all her powers into play spontaneously. It was one of those moments (how they were reached in Japan and how destroyed we must wait for Mr. Waley to explain) when it was natural for a writer to write of ordinary things beautifully, and to say openly to her public, “It is the common that is wonderful, and if you let yourselves be put off by extravagance and rant and what is surprising and momentarily impressive you will be cheated of the most profound of pleasures.” For there are two kinds of artists, said Murasaki: one who makes trifles to fit the fancy of the passing day, the other who “strives to give real beauty to the things which men actually use, and to give them the shapes which tradition has ordained.” How easy it is, she said, to impress and surprise; “to paint a raging sea monster riding a storm”—any toy maker can do that, and be praised to the skies. “But ordinary hills and rivers, just as they are, houses such as you may see anywhere, with all their real beauty and harmony of form—quietly to draw such scenes as this, or to show what lies behind some intimate hedge that is folded away far from the world, and thick trees upon some unheroic hill, and all this with befitting care for composition, proportion, and the like—such works demand the highest master’s utmost skill and must needs draw the common craftsman into a thousand blunders.”

Something of her charm for us is doubtless accidental. It lies in the fact that when she speaks of “houses such as you may see anywhere” we at once conjure up something graceful, fantastic, decorated with cranes and chrysanthemums, a thousand miles removed from Surbiton and the Albert Memorial. We give her, and luxuriate in giving her, all those advantages of background and atmosphere which we are forced to do without in England today. But we should wrong her deeply if, thus seduced, we prettified and sentimentalised an art which, exquisite as it is, is without a touch of decadence, which, for all its sensibility, is fresh and childlike and without a trace of the exaggeration or languor of an outworn civilisation. But the essence of her charm lies deeper far than cranes and chrysanthemums. It lies in the belief which she held so simply—and was, we feel, supported in holding by Emperors and waiting maids, by the air she breathed and flowers she saw—that the true artist “strives to give real beauty to the things which men actually use and to give to them the shapes which tradition has ordained.” On she went, therefore, without hesitation or self-consciousness, effort or agony, to tell the story of the enchanting boy—the Prince who danced “The Waves of the Blue Sea,” so beautifully that all the princes and great gentlemen wept aloud; who loved those whom he could not possess; whose libertinage was tempered by the most perfect courtesy; who played enchantingly with children, and preferred, as his women friends knew, that the song should stop before he had heard the end. To light up the many facets of his mind, Lady Murasaki, being herself a woman, naturally chose the medium of other women’s minds. Aoi, Asagao, Fujitsubo, Murasaki, Yugao, Suyetsumuhana, the beautiful, the red-nosed, the cold, the passionate—one after another they turn their clear or freakish light upon the gay young man at the centre, who flies, who pursues, who laughs, who sorrows, but is always filled with the rush and bubble and chuckle of life.

Unhasting, unresting, with unabated fertility, story after story flows from the brush of Murasaki. Without this gift of invention we might well fear that the tale of Genji would run dry before the six volumes are filled. With it, we need have no such foreboding. We can take our station and watch, through Mr. Waley’s beautiful telescope, the new star rise in perfect confidence that it is going to be large and luminous and serene—but not, nevertheless, a star of the first magnitude. No; the lady Murasaki is not going to prove herself the peer of Tolstoy and Cervantes or those other great story-tellers of the Western world whose ancestors were fighting or squatting in their huts while she gazed from her lattice window at flowers which unfold themselves “like the lips of people smiling at their own thoughts.” Some element of horror, of terror, of sordidity, some root of experience has been removed from the Eastern world so that crudeness is impossible and coarseness out of the question, but with it too has gone some vigour, some richness, some maturity of the human spirit, failing which the gold is silvered and the wine mixed with water. All comparisons between Murasaki and the great Western writers serve but to bring out her perfection and their force. But it is a beautiful world; the quiet lady with all her breeding, her insight and her fun, is a perfect artist; and for years to come we shall be haunting her groves, watching her moons rise and her snow fall, hearing her wild geese cry and her flutes and lutes and flageolets tinkling and chiming, while the Prince tastes and tries all the queer savours of life and dances so exquisitely that men weep, but never passes the bounds of decorum, or relaxes his search for something different, something finer, something withheld.

(Koten o yonde)

Standard literary histories typically describe Masamune Hakuchō (1879–1962) as an important minor author who stands slightly outside the center of the Japanese naturalist movement and emphasize his penchant for fiction steeped in nihilism, skepticism, and irony. He is also seen as a worshipper of the West, an impression that Tanizaki Jun’ichirō summed up nicely when he wrote in 1932 that “there can’t be many authors over the age of forty writing today who are as skeptical of the value of their motherland’s traditions and as partial to the literature of the West as Mr. Hakuchō.”55 In fact, Hakuchō continued writing for half a century after the naturalist movement petered out, and although the stories he produced in the first decade or so of his career do exhibit many of the characteristics associated with the naturalist style, this is by no means true of his work as a whole, which includes translations, plays, and a large body of extremely interesting criticism. The image of Hakuchō as a naive, uncritical devotee of all things Western is also, one might argue, greatly exaggerated.

If Hakuchō is remembered by literary historians for a handful of his early stories and for his critical writings about Dante and other Western writers, he remains infamous among scholars of The Tale of Genji for a series of four essays published between 1926 and 1955 that contain some unflattering descriptions of the text of Genji itself (“its sentences are like bodies with their heads chopped off, tottering unsteadily this way and that—maddening things to read”)56 but say very complementary things about Arthur Waley’s English translation. The scholar Chiba Shunji went so far as to say that Hakuchō’s statements on Genji and its English translation are the ultimate symbol of the “ironic” position that Genji has occupied in modern Japanese literature.57 It is not difficult to see why many scholars of Genji might agree with this statement. At the same time, not all readers of Hakuchō’s essays saw things in this way: a newspaper column in 1933 noted that “for us, living in the modern age, a text like Genji that’s written in the old language is totally unreadable—it’s only after we translate the thing into a foreign language that we can read it, even if we do have to keep consulting the dictionary…foreign countries are still closer than the past.”58 One might argue that Hakuchō’s four essays on Genji encourage us to consider the ironic position that Genji scholarship—rather than the work itself—has occupied in modern and contemporary Japan. Hakuchō’s essays, including “On Reading the Classics,” push us contemporary readers to think more about what we are doing when we read Genji, what or whose standards we use in evaluating it, and how we define its relevance to our own times and lives.

“On Reading the Classics,” which first appeared in August 1926 in the magazine Chūōkōron and was reprinted in a collection of critical essays, Bungei hyōron (1927), is the first of Hakuchō’s four essays on Genji.59 Hakuchō makes no reference to the English translation of Genji in this piece because he had no idea when he wrote it that one was being written (the second volume of Arthur Waley’s six-volume The Tale of Genji was published in February 1926). Even so, translation figures prominently in this essay. “On Reading the Classics” contains what may be the single most infamous sentence ever written about The Tale of Genji: “Say what you like about the content, the writing is incomparably bad.” It may surprise readers who have come across this phrase but never have seen it in context to learn that the essay in which it appears is not an attack on Genji but, rather, a nuanced, wide-ranging, and thought-provoking meditation on the potentials of translation and the importance of literary style.

MICHAEL EMMERICH

I started reading The Dream of the Red Chamber60 and The Tale of Genji; then, partway through, I gave up. Unless at some later date I find myself with a great deal of time on my hands, I doubt that I will ever feel the urge to continue reading these two great and celebrated novels of the Chinese and Japanese traditions….

At the same time that I was agonizing over the literal translation of The Dream of the Red Chamber, I was also reading The Tale of Genji and feeling disgusted at its slipshod, lax, and rambling writing. Granted, it is a classical work that appeared some thousand years ago. Nonetheless, I was born in the same country as its author, and I’ve spent a fair amount of time studying the old language ever since I was a boy—it’s strange that I feel such hatred for this tale, generally thought to be Japan’s greatest masterpiece. But the fact is that I have never before encountered a work so difficult to read. I feel more interest in the great classics of the West, the Iliad, the Odyssey, and so on, so at least I am able to keep reading them; but when it came to Genji, a work viewed as a national treasure in the literature of my own country, I found myself yearning, more times than I could count, to hurl it against the wall. Say what you like about the content, the writing is incomparably bad. The very idea of including a work like this in a textbook in this day and age strikes me as absurd. I’m sure even Genji would be more engaging when read in an English translation.61