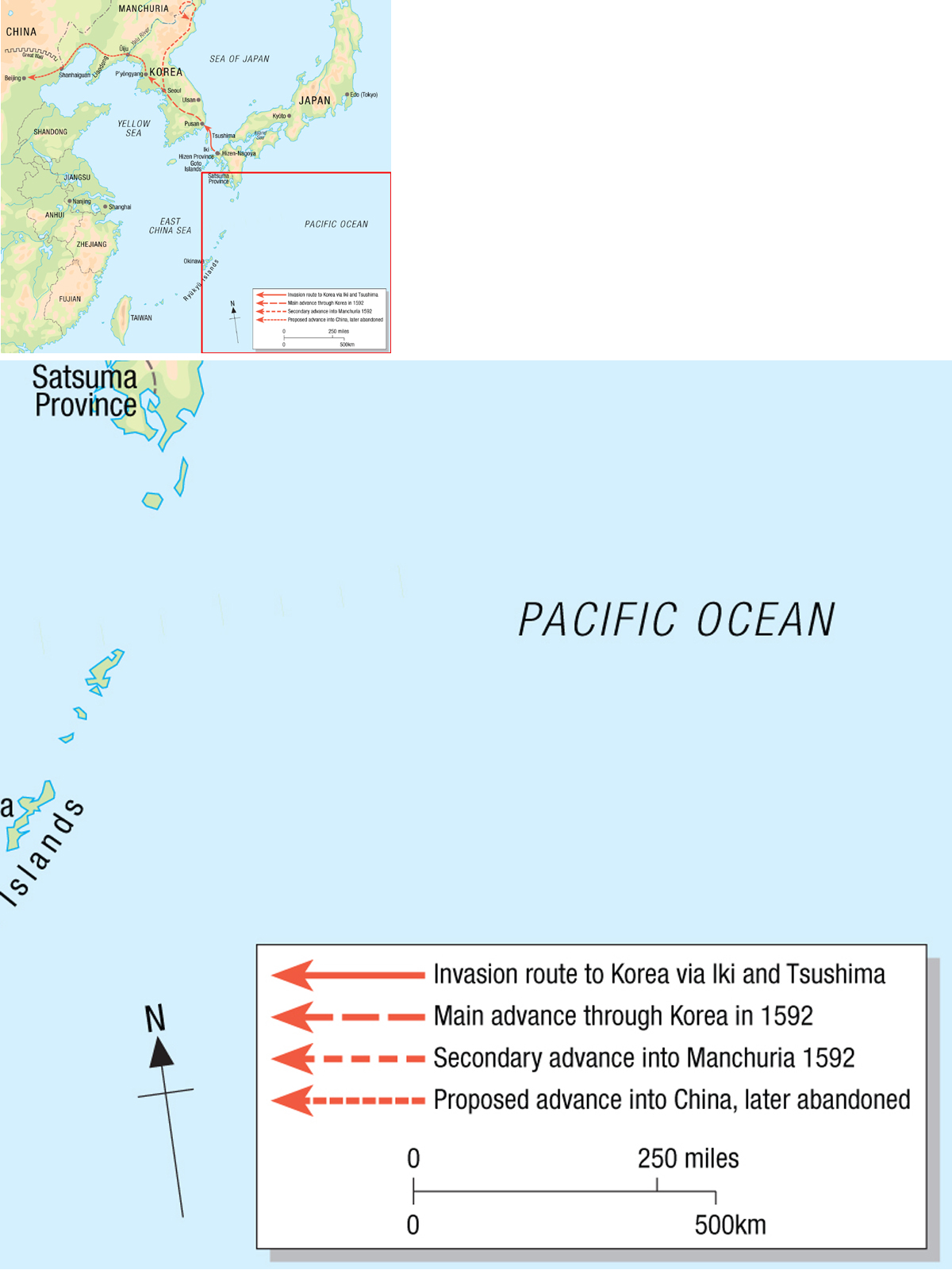

Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s strategic plans of campaign were based on certain assumptions drawn from what he had learned from the limited overseas expeditions carried out by the wakō on China. The first envisaged the submission of the Korean king either by negotiation or warfare, just as his domestic rivals had done, with no involvement from China. Hideyoshi’s plans also dismissed the possibility of any intervention by the Korean navy. The invasion would therefore begin with an unopposed landing and a blitzkrieg attack that would take Seoul within days. With the Korean army as his allies and the Korean people to feed his army, massive reinforcements could be shipped over to the peninsula. There would then be an assault across the Yalu River, a march round the coast, through the Great Wall and on to Beijing.

Yet all these assumptions were flawed. The experience of the earlier raids had certainly indicated that pirates based in Japan had once acted with impunity, but that impression was long out of date, because by the end of the 1560s the wakō were being regularly defeated by Chinese generals. The Korean navy had also destroyed Japanese pirate ships owing to its superiority with cannon. Nor did Hideyoshi appreciate the tributary relationship between China and Korea. Instead his ignorance of the position was so great that he seems to have believed that Korea was in some way under the control of the daimyō of Tsushima. As events turned out, however, Hideyoshi’s strategic assumptions would prove to be correct in the short term and disastrously wrong in the long term. There was indeed a rapid collapse of Korean resistance, but this was to be followed by Korean naval victories and a decisive Chinese intervention.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who is regarded as the Japanese equivalent of Napoleon Bonaparte, was an accomplished general who inspired fierce loyalty in his followers and finally achieved the reunification of Japan. The invasion of Korea was his last campaign and his only failure. This painting of him in armour hangs in the Hōsei Nikō Kenshōkan in Nakamura Park, Nagoya.

At a tactical level Hideyoshi’s battle plans were less fanciful but much more limited in their time scale. The landings were planned to take place in three major phases around Pusan, but any direction after the initial landings grew progressively more vague as the armies were directed northwards. Seoul was of course the primary target, so Hideyoshi envisaged the three armies converging for an attack, but beyond Seoul the plans of attack seemed to evaporate completely, a lack of direction that was to be realized on the ground.

The wajō (Japan’s coastal forts) provided the last line of defence for the Japanese when their second invasion went into reverse. This scene from Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi shows perfectly the strong but temporary nature of the wajō.

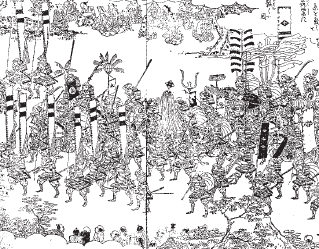

Konishi Yukinaga led the First Division during the invasion of Korea and continued to play a leading role throughout the war. It was Yukinaga who captured P’yŏngyang and was then forced to abandon it when the Chinese counterattacked. In 1597 he was almost the last general to leave Korea. This illustration of his army on the march is taken from Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

Korea’s lack of planning for the invasion was partly responsible for the early Japanese successes. The wakō raid of 1555 may have been an awful memory, but all the lessons that may have been learned from it were lost. There was still a centralized command system that operated from Seoul with troops being raised locally and moved to the scene of trouble as quickly as possible. Korea’s great strength in defensive preparations lay with its formidable navy, which had the resources and the firepower to locate the Japanese invasion fleet and possibly destroy it even before it left Tsushima. But Korea’s navy suffered from incompetent commanders in the sea areas through which the invasion fleet was likely to pass. Both failed to see the fleet, and when the Japanese entered Pusan Harbour one ran away and the other scuttled his ships.

The Chinese plans were always to cross the Yalu River and drive the Japanese back into the sea, but unfortunately the Korean request for help could not have come at a worse time for the Chinese. A serious mutiny had occurred in Ningxia in the north-west of China, and troops who would normally have been garrisoning the Liaodong Peninsula, and thus could have made an immediate response to a Japanese invasion of Korea, were many hundreds of kilometres away. Li Rusong, the general who was eventually to recapture P’yŏngyang, was actively fighting in Ningxia while the Japanese swept through Korea, and it was early 1593 before the Chinese were able to put their plans into action on an appropriate scale.