Throughout the entire course of the war Toyotomi Hideyoshi never set foot in Korea, and instead left the full control of operations to the generals he trusted so well. In a tactical sense, therefore, Hideyoshi cannot be considered as one of the commanders, but, as his will drove the whole project along until he died, his political influence cannot be underestimated.

Contemporary observers note his small, wizened stature and the total lack of noble features on his monkey-like head, yet as his power grew Hideyoshi took on aristocratic trappings on a grander scale than any ruler before him. This was in marked contrast to his humble beginnings, because his father had been a peasant farmer who had served as an ashigaru (footsoldier) until a bullet wound invalided him out. Hideyoshi, then called Tokichirō, followed in his father’s footsteps and served the daimyō Oda Nobunaga (1534–82) as the latter grew to become the first of Japan’s great unifiers. Nobunaga had an eye for talent, and rewarded Tokichirō’s successive military accomplishments by rapid promotion until, by the time of Nobunaga’s murder in 1582, Hideyoshi was his most loyal general. He then became Nobunaga’s avenger, and the kudos associated with this fact gave Hideyoshi the opportunity to fill the power vacuum that Nobunaga’s death had left. During the next two years Hideyoshi was to challenge and defeat all other rivals, including Nobunaga’s surviving sons, in a series of brilliant military campaigns. By 1585 Hideyoshi was able to begin extending the boundaries of Nobunaga’s former conquests, taking in the island of Shikoku and the provinces of western Japan. The Shikoku campaign involved a successful sea crossing, and in 1587 Hideyoshi conquered the great southern Japanese island of Kyūshū in a huge and well-coordinated campaign that was to provide a model for the Korean expedition. The defeat of the Hōjō in 1590, which involved mobilizing the largest army ever seen in Japan, led to most of the northern daimyō submitting without a fight.

Konishi Yukinaga (1558–1600), whom Hideyoshi chose to lead the invasion in 1592, was the daimyō of Uto in southern Higo province in Kyūshū. His unfortunate later life, which involved choosing the wrong side before the battle of Sekigahara and being executed after it, has robbed posterity of any portrait of him or any mementoes of his earlier, glorious career. It had been his political talents rather than his military skills that had first brought Konishi to Hideyoshi’s attention when he had been employed by his master Ukita Naoie in negotiating the bloodless surrender of the Ukita domains to Hideyoshi. Loyal service during the Kyūshū campaign earned him the fief of Uto. He was baptized in 1583, and is known in the Jesuit accounts as Dom Agostinho (Augustin). Konishi Yukinaga’s presence dominated the whole of the Korean expedition. He was the first commander to land and the last to leave.

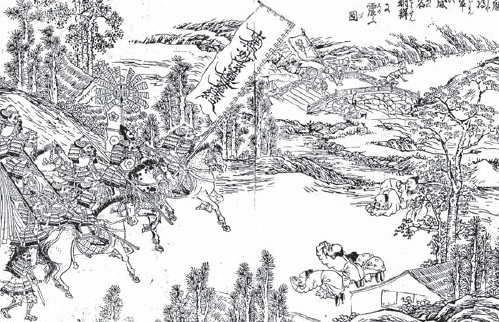

Known to the Koreans as the ‘devil general’, Katō Kiyomasa commanded the Second Division of the Japanese army. Following the fall of Seoul Kiyomasa pacified the northeast of Korea and made a brief incursion into Manchuria. He was to earn great glory at the siege of Ulsan in 1598. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

Katō Kiyomasa, who led the Second Division of the Japanese army, was born in the village of Nakamura, which has long since been swallowed up within the modern city of Nagoya. He was called Toranosuke (the young tiger) in his childhood, and was the son of a blacksmith who died when the boy was three years old. Because of a familial relationship between the two boys’ mothers, Toyotomi Hideyoshi took Toranosuke under his wing when his father died.

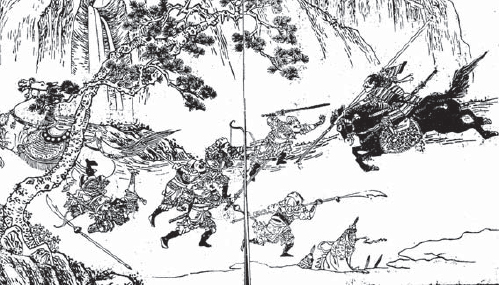

Katō Kiyomasa soon proved to have a considerable aptitude for the military life, and the first opportunity to demonstrate it came at the age of 21 with the battle of Shizugatake, where the absence of a flat battlefield and lines of harquebus troops allowed the individual samurai spirit to be expressed in an unfettered way. Katō Kiyomasa fought from horseback in classic style with the support of a loyal band of samurai attendants, and wielded his favourite cross-bladed spear to great effect. It was not long before a number of enemy heads had fallen to Kiyomasa, so to intimidate his opponents one of his attendants tied the severed heads to a long stalk of green bamboo and carried it into Katō’s fresh conflicts like a general’s standard. Katō Kiyomasa was named that day as one of the ‘Seven Spears of Shizugatake’ – the most valiant warriors, and from that time on his fortunes prospered.

In 1585 Katō Kiyomasa received from Hideyoshi the important role of inspector of taxes, and in 1588 he began a long association with the island of Kyūshū. He was based in the castle town of Kumamoto, where statues of Kiyomasa show him in full armour with a striking helmet design. It was supposed to represent a courtier’s cap, and was made by building up a crown of wood and papier mâché on top of a simple helmet bowl. Some portraits of Kiyomasa also show him with an extensive beard, which was quite unusual for a samurai. In contrast to Konishi Yukinaga’s Catholicism, Kiyomasa was an adherent of the Nichiren sect of Buddhism, and flew as his battle standard a long white pennant which bore, in characters said to have been written by Nichiren himself, the slogan Namu Myōho Renge Kyō (Hail to the Lotus of the Divine Law), the motto and battle cry of his followers. Partly because of their religious differences, but chiefly because of old-fashioned samurai rivalry, there was great enmity between the two leading commanders, and for almost the whole of the campaign the pair fought in different places.

Admiral Yi Sunsin is Korea’s greatest hero. By a series of naval victories he cut off the Japanese lines of communication and ensured that the retreat set in motion by the Chinese victories ended with a Japanese withdrawal. Statues of Yi Sunsin abound. This one is in the grounds of a school in Ungch’ŏn.

Wakizaka Yasuharu (1554–1620) was one of Hideyoshi’s leading naval commanders during the campaign. Born in 1554, Yasuharu had served Hideyoshi loyally at the battle of Shizugatake in 1583, where he had become another of the ‘Seven Spears’. In 1585 he had received in fief the island of Awaji in the Inland Sea, and the notorious whirlpools that are created there under certain tidal conditions must have acquainted him very rapidly with the dangers of seafaring. When the Korean campaign began Wakizaka was one of three commanders placed in charge of naval matters for the Tsushima theatre, and was transferred to land-based duties at Yong’in as soon as the army had landed. He returned to naval command shortly afterwards, and was the loser in the great battle of Hansando. He survived the Korean campaign, fought at Sekigahara in 1600 and immediately afterwards took the castle of Sawayama, the headquarters of the victorious Tokugawa’s defeated enemy. For this he was richly rewarded.

Chŏng Pal (1553–92) was the first Korean commander to feel the brunt of the Japanese invasion. He passed the state examination for a military career in 1579 and served as a royal messenger and then district magistrate of Kŏje Island before becoming garrison commander of Pusan. Being taken by surprise by the Japanese invasion he organized the defence of Pusan but perished in the fighting.

Admiral Yi Sunsin (1545-98) is Korea’s greatest hero, and is one of the outstanding naval commanders in the entire history of the world. He was born in 1545, and received the thorough Confucian education that was so necessary for men of his social station. Yi passed the military service examinations in 1576, after which he was appointed to his first command in Hamgyŏng Province. After a brief spell in a naval command in Chŏlla Province in 1580, he was moved back to the army and saw action against the Jurchens in Hamgyŏng Province in 1583, distinguishing himself in one particular battle beside the Tumen River where he enticed the Jurchens forwards with a false retreat. In 1587 he fell foul of the political and factional rivalry that plagued Korean society, and found himself back in the ranks as a common soldier after annoying General Yi Il. Fortunately for Korea, Yu Sŏngnyŏng, the future prime minister of Korea, was a rising star at court and had been Yi’s boyhood friend, so through Yu’s influence Yi was reinstated and new responsibilities soon followed. In 1591, following Yu’s recommendation, Yi Sunsin was appointed to the post of Left Naval Commander of Chŏlla Province, where he threw himself enthusiastically into his duties as the Japanese threat loomed ever nearer. Had Yi been in command in the Pusan area the Japanese landings may never have happened. His naval victories were to prove decisive in the Japanese defeat, although Yi was to die during his final battle in 1598.

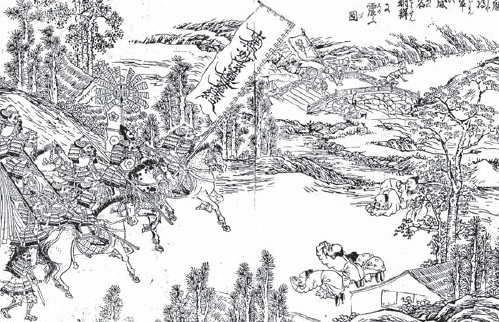

Li Rusong, the distinguished commander of the Chinese armies that liberated Korea, is depicted here in his only defeat. Having recaptured Py’ŏngyang, Li was caught in a rearguard action at Pyŏkjeyek to the north of Seoul. He was knocked off his horse and only saved from death by the quick thinking of a subordinate general Li Yousheng. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

Kwŏn Yul was the outstanding Korean general of the invasion, and stands head and shoulders above his largely incompetent contemporaries. He was promoted from being Magistrate of Kwangju to being commander of Chŏlla Province when the invasion began, and showed a willingness to coordinate his own efforts with those of the irregular forces and the warrior monks. He defeated a Japanese army at the battle of Ich’i, and provided a heroic defence of the mountain fortress of Haengju, a victory that was instrumental in forcing the Japanese to evacuate Seoul.

Dismissed in traditional Japanese accounts of the war for being the loser at the battle of Pyŏkjeyek in 1593, a Japanese victory that did nothing to halt the Japanese evacuation of the capital, Li Rusong was in fact one of Ming China’s most accomplished generals. While the Japanese were invading Korea Li Rusong was in command against the rebels in Ningxia, and it is testimony to the high regard in which he was held that the Wanli Emperor had bestowed upon him the title of tidu (military superintendent), a position that allowed him direct access to the throne, supreme military command in the field and the power to impeach other officials. His conduct in Ningxia justified the confidence that the Ming emperor had in him, and he was reappointed to the post on taking command of the Korean effort. His recapture of P’yŏngyang was to be the turning point in the Korean campaign, and, although massively defeated in the Japanese rearguard action at Pyŏkjeyek, Li rallied and followed through to drive the Japanese to the coast.