The elite troops of the Japanese army were the famous samurai, the knights of old Japan. Traditionally, they had been the only warriors to own and ride horses. Centuries before their primary role had been to act as mounted archers, although this skill was rarely displayed on a battlefield by 1592. Instead their usual weapon was now the yari (spear), a weapon unsuitable for slashing but ideal for stabbing – the best technique to use from a saddle. A useful variation was a cross-bladed spear that enabled a samurai to pull an opponent from his horse. If a samurai wished to deliver slashing strokes from horseback then a better choice was the naginata, a polearm with a long curved blade, or the spectacular nodachi, an extra long sword with a very strong and very long handle. Yari would also be the samurai’s primary weapon of choice when he had to fight dismounted.

The samurai’s other main weapon was of course the famous katana – the classic samurai sword. Forged to perfection, and with a razor-sharp edge within a resilient body, this two-handed sword was the finest edged weapon in the history of warfare. Every samurai possessed at least one pair of swords, the standard fighting sword and the shorter wakizashi. Contrary to popular belief, both seem to have been carried into battle along with a tantō (dagger). The samurai never used shields. Instead the katana was both sword and shield, its resilience enabling the samurai to deflect a blow aimed at him by knocking the attacking sword to one side with the flat of the blade and then following up with a stroke of his own.

In the press of battle the swinging of a sword was greatly restricted, and Japanese armour gave good protection, so it was rare for a man to be killed with one sweep of a sword blade. Sword fighting from a horse was not easy, because the normally two-handed sword had to be used in one hand, but this disadvantage was somewhat overcome by the samurai’s position above a foot soldier and the momentum of his horse. The process was helped by the curvature of the sword’s blade, which allowed the very hard and very sharp cutting edge to slice into an opponent along a small area that would open up to cut through to the bone as the momentum of the swing continued.

By 1592 the traditional style of Japanese armour, whereby armour plates were made from individual lamellae (iron or leather scales) laced together, had become modified to allow solid plate body armours that gave better protection against gunfire. Lamellar sections, however, continued to be found in the thigh guards and shoulder guards. Armoured sleeves for the arm and shinguards protected those areas of the body. An iron mask that provided a secure point for tying the helmet cords protected the face. The mask was often decorated with moustaches made of horsehair, and the mouthpiece might well sport a sinister grin around white teeth! The helmet was a very solid affair, but senior samurai, and many daimyō would use the design of the helmet crown to build up the surface of an iron helmet into fantastic shapes.

The other way by which an individual samurai would be recognized in the heat of battle was by wearing on his back a small identifying device called a sashimono. This was often a flag in a wooden holder with the daimyō’s mon (family crest) on a coloured background. This would be the case for most rank-and-file samurai too, but senior samurai would be allowed to have their own mon, or sometimes their surname displayed on the flag.

The Japanese army was very well organized. Under Hideyoshi the ashigaru (footsoldiers) had finally been integrated into the standing armies of daimyō as the lowest ranks of the samurai. They were organized in weapons squads armed with either long spears, harquebuses or bows, while some provided attendance on the daimyō or on senior samurai, as grooms, weapon bearers, bodyguards, standard bearers and the like. The ashigaru wore simple suits of iron armour that bore the mon of the daimyō, a device that also appeared on the simple lampshade-shaped helmet and on the flags of the unit. The ashigaru were trained to fight in formation. The spearmen provided a defence for the missile troops, and could also act in an offensive capacity with their long spears. The most important Japanese infantry weapon was the harquebus. Its inaccuracy and slowness in reloading was compensated for by the use of massed volley firing, for which the ashigaru were highly trained.

The timing of the invasion of Korea meant that the Chinese army was required to be in three places at once: the Korean border, the south-west of China where an aboriginal chieftain was carrying out a rebellion, and in Ningxia where the mutiny of Pubei, the last serious Mongol threat to Ming supremacy, had to be suppressed. It is not therefore surprising that the contribution made by the Ming towards the relief of Korea, aid that had been requested even before the Japanese had set sail, should appear to be a case of ‘too little, too late’.

The Ming army was certainly not the force it once had been. The traditional system of frontier defence of the early Ming had come to an end after the Tumu Incident of 1449, and the regular army, the core of which consisted of mercenary troops, had deteriorated in both quality and quantity. However, military organization was generally good and well provided with reinforcements which could be moved readily by land. In the Ningxia campaign the Ming army successfully transported 400 artillery pieces over 480km of difficult terrain.

The army had also been reorganized successfully by Qi Jiguang, who had triumphed against the wakō and had published a book on military matters in 1567, which later came to the attention of the Koreans. Qi’s system, controlled by strict discipline, divided the infantry into five groups: firearms, swordsmen, archers with fire arrows, ordinary archers and spearmen, all of whom were backed up by cavalry and artillery crews. Many of the cavalry were mounted archers, while the Chinese footsoldiers used crossbows and were well supplied with firearms, including harquebuses.

The iron helmet of a Korean officer, ornamented with gold and with a protective neck cover of studded leather and fabric. (Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds)

The basic design of a suit of Chinese armour was made from lamellae of iron or leather made into different sections with a rounded conical iron helmet. Simpler armour consisted of a three-quarter-length heavy coat, reinforced in different ways, and worn over an inner garment that resembled a divided apron, with trousers and leather boots. The coat usually had sleeves, either full sleeves or short ones. The heads of rivets, which held in place small plates inside the armour, protruded from its outside surface to give an appearance very similar to brigandine. Alternatively, a brigandine coat could be made by sewing metal or leather plates so that each overlapped the one below it. Separate shoulder protectors were occasionally used.

Chinese field artillery and siege cannon were the finest in the region. The first Chinese guns were of cast bronze, but cast iron was being used in China from 1356 onwards. A Ming edict of 1412 ordered the i stationing of batteries of five cannon at each of the frontier passes as a I form of garrison artillery. Some designs of Chinese cannon saw very long I service. For example the ‘crouching tiger cannon’, which dated from 1368, was still being used against the Japanese in Korea in 1592. It was I fitted with a curious loose metal collar with two legs so that it needed no external carriage for laying. Another was the ‘great general cannon’, of which several sizes existed, and an account of 1606 notes that 300 different great general guns were made in 1465. Ye Mengxiong, who lived in the second half of the 16th century, ‘changed the weight of the gun to 250 catties [150kg] and doubled its length to six feet, but eliminated the stand and it is now placed on a carriage with wheels. When fired it has a range of 800 paces.’ The enthusiastic description continues:

A single shot has the power of thunderbolt, causing several hundred casualties among men and horses. If thousands, or tens of thousands, were placed in position along the frontiers, and every one of them manned by soldiers well trained to use them, then [we should be] invincible. … At first its heavy weight caused some doubt as to whether or not it was too cumbersome; but if it is transported on its carriage then it is suitable, irrespective of height, distance, or difficulty of terrain.

It is more than likely that great general guns made up much of the 700-piece artillery train that the Ming used in their campaign against rebels in Ningxia in 1592, just prior to joining in the Korean campaign against Japan.

From the early 16th century onwards a different type of gun entered the Chinese arsenal. It was known as the folang zhi, which means ‘Frankish gun’, ‘the Franks’ being a general term for any inhabitants of the lands to the west, and was of a fundamentally different design from the ‘great general’, because these new weapons were breech loaders. The ball was placed inside from the breech end, while powder and wad were introduced into the breech inside a sturdy container shaped like a large tankard with a handle. The main disadvantage was leakage around the muzzle and a consequent loss of explosive energy, but this was compensated for by a comparatively high rate of fire, as several breech containers could be prepared in advance.

In contrast to Japan, the senior officers of the Korean army tended to be social aristocrats rather than military ones. Several good generals were produced by the system, but there were many bad ones too. The Korean army therefore tended to be loosely organized and quite haphazard. The practice of sending generals from Seoul to command local troops was also a major weakness, while the garrison soldiers were almost totally untrained, disorganized and ill disciplined.

Korea’s close proximity to China ensured that the evolution of Korean armour followed that of China rather than Japan. The Korean helmet consisted of a simple rounded conical bowl made from four main pieces riveted together and secured round the brow. A neckguard of lamellae or brigandine was suspended from it in three sections, and decoration in the form of feathers could be flown from the helmet point. Korean foot soldiers wore no armour at all, just their traditional white clothes with a sleeveless black jacket and a belt. A stiffened felt hat gave some small protection in battle.

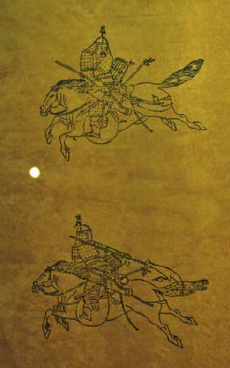

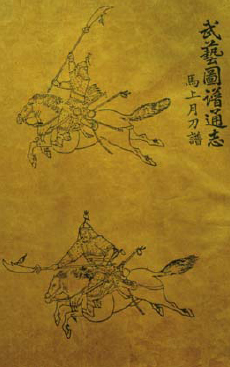

Korean cavalry exercising with halberds, from an illustrated scroll in the War Memorial Museum, Seoul (reproduced by kind permission).

Early Korean swords were two-edged, straight-bladed weapons, a design that remained popular, although curved swords like Japanese katana were also made, and actual Japanese models were imported. By contrast, Korean polearms show considerable Chinese influence. Their use was most prized from the back of a horse, so we see cavalrymen armed with tridents, long straight spears and glaives with heavy curved blades much wider than a Japanese naginata. Unique to Korea, however, was the flail, a rounded hardwood stick, painted red and 1.5m long, to which was attached a shorter and heavier mace-like shaft studded with iron nails or knobs. A short length of chain provided the attachment. Foot soldiers were armed with all the above varieties of polearm except the flail. Prowess at archery was greatly valued, and the famous Admiral Yi Sunsin was an accomplished archer. The ordinary Korean bow was a composite reflex bow, made from mulberry wood, bamboo, water buffalo horn and cow sinew spliced together. It had a pronounced negative curve, against which the bow had to be pulled in order to string it. A Japanese source from the time of the 1592 invasion claims that Korean bows were the one thing in which the Koreans were superior to the Japanese, because their range was 450m against the Japanese longbow’s range of 300m. However, by this time the Japanese bow had largely been abandoned in favour of the harquebus. Arrows were made of bamboo, but not lacquered after the Japanese fashion. Simple leather quivers were used.

At the time of the Japanese invasions the most marked deficiency in weaponry between Korea and Japan lay in the field of personal firearms. Korea had adopted the Chinese-style handgun a century and a half before it was introduced to Japan, and had developed it into the Korean sŭngja (victory gun), a form of simple musket that took the clumsy weapon to its modest peak of perfection. However, the quality and number of Korean cannon provided a direct contrast to the situation that existed with firearms. The heavy cannon used on board Korean ships from the early 15th century onwards had no equivalent in Japan. They could shoot cannon balls of iron or polished stone, but the favourite missile was the wooden arrow, winged with leather and tipped with iron, which caused immense destruction when it struck the planking of a Japanese vessel. Fire arrows loosed from ordinary bows were also important, and some of the larger cannon-based arrows could be converted into fire arrows. Korea also developed certain specialized weapons of its own. One of the most interesting and effective of these was the mortar, used for firing stones, balls or bombs. The bombs used a clever double-fuse system, a fast burning fuse for the mortar, and a slower one for the bomb itself. The operator would light both fuses simultaneously. For mobility the mortars, which came in three basic sizes, were mounted on wooden carriages. The other innovative Korean weapon was the curious armoured artillery vehicle called a hwach’a (fire wagon), which fired a volley of rockets.

Korea’s greatest strength lay with its navy. The standard fighting ship the p’anoksŏn may not have been much better than the equivalent Japanese vessel, but had a vast superiority in firepower from cannon. The famous turtle ships became the pride of the fleet, although their numbers seem to have been small during the Japanese campaign. There is no space here to describe the turtle ships in detail, as I did in New Vanguard 63: Fighting Ships of the Far East Volume 2 (Osprey Publishing Ltd: Oxford, 2003), but it is important to note that the actual design of the turtle ship is still controversial. Until recently it was assumed that it was much longer than it was wide. This is how it is commonly represented, but it is now believed that it may have been almost literally turtle shaped to account for its manoeuvrability. Arguments have also been put forward to claim that it must have been three-decked, not two-decked, so that the artillerymen on the upper deck did not interfere with the oarsmen on the lower deck.

Detailed orders of battle are only available for the Japanese side. Chinese and Korean numbers will be given as appropriate in the description of individual actions.

The numbers of Japanese troops who took part in the invasion are well documented, although there are small discrepancies between different sets of figures, which are largely explained by the inclusion or omission of reserve corps from the various lists. The most reliable source, an order of battle sent by Hideyoshi to Mōri Terumoto, gives an overall structure of vanguard, main body, rearguard and reserves, totalling approximately 158,800 men. Hideyoshi’s plans envisioned that the First Division would establish a bridgehead at Pusan under Konishi Yukinaga, who was to be joined by the Second Division under Katō Kiyomasa for the drive north. The final vanguard unit, the Third Division under Kuroda Nagamasa, was to attack to the west of Pusan across the Naktong River. They were to be joined within a few days by the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh divisions totalling 84,700 men, while the Eighth and Ninth Divisions of 21,500 men were to be held in immediate reserve on the islands of Tsushima and Iki respectively. When war began the Ninth Division was moved forwards to Tsushima. There was also a sizeable rearguard left in reserve in Japan, named in some accounts as the Tenth Division, while Hizen-Nagoya Castle was garrisoned by 27,000 troops under Hideyoshi’s personal command, together with over 70,000 men supplied by the eastern daimyō who stayed in reserve in the castle town. Even those who did not expect to see their forces cross the seas suffered some disruption with the stationing of thousands more as the final rearguard near Kyoto. A whole nation was at war.