The first shots of the Korean campaign were fired against the defences of Pusan, the vast natural harbour that is still South Korea’s main port. Having travelled via Iki and Tsushima, the Japanese fleet rested overnight in Pusan Harbour, completely unmolested by the Korean navy, whose local commander, Wŏn Kyun, was an incompetent coward. Dividing their forces, Konishi Yukinaga and Sō Yoshitomo led simultaneous early morning attacks against the main city walls of Pusan and a subsidiary harbour fort called Tadaejin, a strategy planned because of the local knowledge possessed by Sō Yoshitomo.

Sō Yoshitomo’s attack on Pusan was countered by Chŏng Pal, the Pusan commander, who had been hunting on Yŏng Island off Pusan Harbour when the invasion fleet was spotted. He rushed back to his post, and a Korean account, which refers to the Japanese only as ‘the robbers’, relates how Pusan held out as long as it could, its garrison killing many Japanese before being overwhelmed. ‘In one day’, it notes, ‘the bodies of the robbers had piled up like a mountain. However, at length the arrows were exhausted and all they could do was wait for reinforcements.’ At that moment Chŏng Pal was suddenly hit by a bullet and died. Chŏng Pal thus became the first senior Korean casualty of the invasion, and is commemorated today in Pusan by a statue that stands, appropriately enough, next to the Japanese Consulate. Morale collapsed with his death, and Pusan soon fell. Chŏng Pal’s concubine wept when she heard of his death and committed suicide next to his dead body. Even Chŏng Pal‘s servant attacked the Japanese lines and was killed. Afterwards one Japanese general commented, ‘Among the generals of your country, the general of Pusan dressed in black must have been the most feared general of all.’

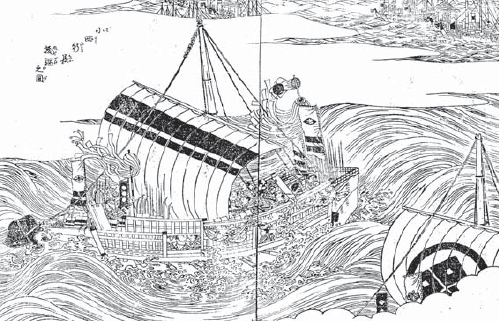

Konishi Yukinaga sets sail for Korea. The Japanese ships, which had little in the way of defensive armaments, are shown here ploughing through the seas on their way to make the first landfall in Korea. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

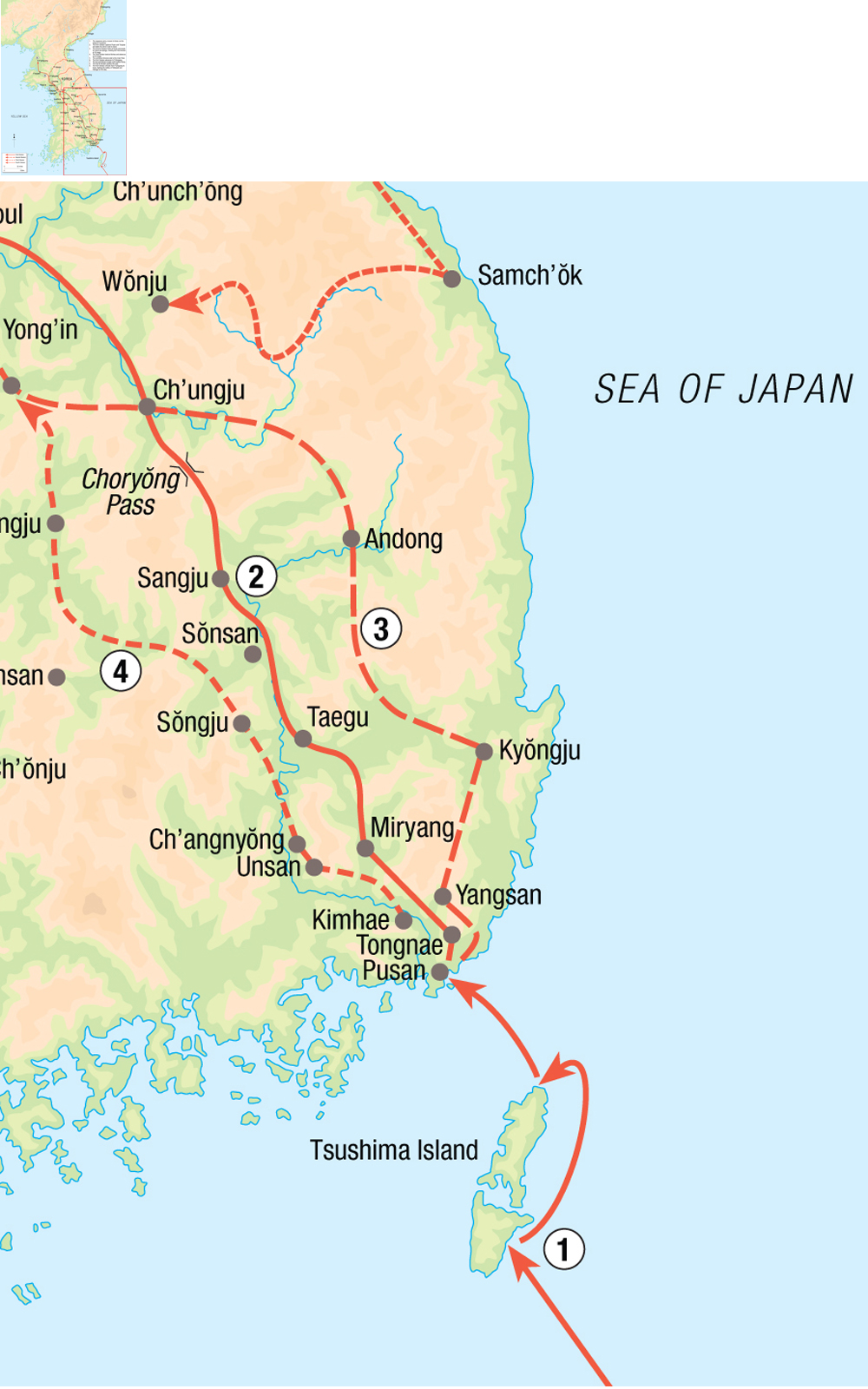

Dressed in his distinctive black armour, the brave Chŏng Pal, the commander of Pusan, is killed during the attack by Sō Yoshitomo. He was the first senior Korean casualty of the invasion. (From a painting in the Ch’ungyŏlsa Shrine, Tongnae, by kind permission)

With the death of the ‘brave general dressed in black’ the Japanese army completed its first objective. Meanwhile, Konishi Yukinaga was leading the assault on the harbour fort of Tadaejin. Rocks and lumber were flung into the moats and ditches, and bamboo scaling ladders were raised for an assault under the cover of volleys of gunfire. Yun Hŭngsin defended Tadaejin bravely, but the castle soon fell and every member of the garrison was put to the sword.

A rapid advance towards Seoul began. A few kilometres to the north of Pusan lay the fortress of Tongnae. Unlike Pusan, Tongnae was a sansŏng (mountain castle) that dominated the main road north towards Seoul. After resting overnight at Pusan, the First Division left at 6am the following morning and began the attack on Tongnae two hours later. The battle provided Korea with its third heroic martyr of the war. Its governor was called Song Sanghyŏn, and it was to this brave young man that Konishi Yukinaga presented anew the Japanese demands for a clear road through to China. It was again rejected with the words, ‘It is easy for me to die, but difficult to let you pass’, so for a third time the ramparts of a Korean castle were swept with bullets. A few weeks a later a liberated Korean prisoner of war described the battle to Admiral Yi Sunsin in these words:

The Japanese gathered in countless numbers and surrounded the city wall in five lines with other troops crowding into the nearby fields. The vanguard, consisting of about 100 men, wearing helmets and armour and each holding a tall ladder, dashed to the city wall together with others and placed bamboo ladders and climbed over the ramparts in many places.

The man added that after the fall of Tongnae many people were killed, which implies a massacre similar to that which had happened at Pusan, where an orgy of indiscriminate killing had even included the beheading of dogs and cats.

Sō Yoshitomo then sent out a small group of samurai with ten ashigaru to scout the position of Yangsan Castle, the next strongpoint on the road towards Seoul that covered the Naktong River. On drawing near, the ten ashigaru fired a volley from their harquebuses, which so terrified the defenders of Yangsan that they immediately abandoned the castle and fled. Yangsan was occupied at dawn the following morning, so the front line of the Japanese bridgehead was moved farther north with ease.

That afternoon, Konishi Yukinaga’s main body left Tongnae, passed Yangsan and headed for the next castle on the road, which was Miryang. There was a minor skirmish en route and Miryang was occupied. The next strongpoint, Taegu, had been deliberately denuded of troops because of the Korean decision to make a stand farther north. Konishi Yukinaga led his army in a crossing of the undefended Naktong River, where his scouts brought him news that a Korean army was waiting for him at the fortress of Sangju. By now the First Division had been on Korean soil for 11 days. They had met virtually no opposition since leaving Tongnae, and had advanced beyond what would have been reasonable limits of safety had it not been for the fact that both the Second and Third divisions had now landed and were covering their flanks to the right and left. A disastrous Korean defeat followed at Ch’ungju. On arriving outside Seoul the capital city was found to have been abandoned. The Korean king had fled to P’yŏngyang, shocked by the sudden collapse of his country’s resistance.

The rapidity of the initial Japanese successes meant that certain officials in the Ming court began to suspect that Korea had abandoned its tributary relationship with China and were actually aiding the Japanese. The Wanli Emperor was so concerned about this that he dispatched an envoy to P’yŏngyang who returned with the news that the loyal Koreans had simply been overcome by sheer force of arms and urgently required Chinese assistance. Wanli was keen to comply, but the Ningxia Mutiny was still raging so all the Chinese could do was to urge the Koreans to hang on as best they could until a Ming army was ready. This was easier said than done, but the Japanese invaders gave the Koreans an unexpected respite shortly after taking Seoul by failing to cross the Imjin River until a Korean raid disclosed its fordable areas.

The assault on the detached harbour fortress of Tadaejin by Konishi Yukinaga. (From a hanging scroll in Pusan Municipal Museum, by kind permission)

A fierce counterattack is launched from Pusan against Sō Yoshitomo. (From a painting in the Ch’ungyŏlsa Shrine, Tongnae, by kind permission)

The Japanese army also unwittingly helped the Chinese by dividing their army in two. Konishi Yukinaga pressed on towards the north along the shortest route to the Chinese border via P’yŏngyang, while his rival Katō Kiyomasa set off on a long campaign to pacify the north-east of Korea. This had some strategic merit because it would cover the eastern flank of any advance into China. At that time Nurhaci (1559–1616), the leader of the Manchurian Jurchens who would eventually overthrow the Ming dynasty in favour of the Later Jin/Qing dynasty (1644–1911), was the Ming’s ally. Katō Kiyomasa succeeded in this objective. A system of taxation and land surveys on the Japanese model followed, interspersed by attacks on Korean fortresses and a brief incursion into Manchuria, but Kiyomasa’s adventure really helped only to diminish the continuing impact of the Japanese invasion, which stalled after Konishi Yukinaga had captured P’yŏngyang. The Korean king fled to the Yalu River and was ready to escape into China whenever the last Japanese push against Korea began. But no further move north was made, and P’yŏngyang was destined to be the last outpost of this new Japanese empire.

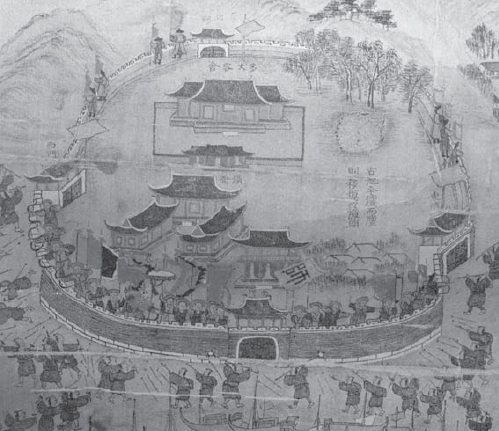

THE JAPANESE CAPTURE THE FORTRESS OF PUSAN FROM THE KOREANS UNDER CHŎNG PAL: 1592 (pp. 28-29)

The harbour fortress of Pusan was part of the city wall, and was the first place to be attacked following the Japanese landing. In this plate we are looking from just inside the main gate as the first Japanese assault breaks in. The fortified gateway is built in typical Korean style, derived from contemporary China, whereby the actual entrance is a dark tunnel with a heavy gate through a stone and brick wall (1). On top of the gateway is an ornate gatehouse pavilion (2). Instead of fighting their way in through the gate the Japanese have however surmounted the wall using scaling ladders under the cover provided by hundreds of harquebus troops firing volleys of bullets. The Japanese assault parties are in small groups. In the background a Korean unit lead a counterattack up the stone steps to the gatehouse.

The troops are led by Sō Yoshitomo, daimyō of Tsushima. Yoshitomo whose family had ancient connections with Korea played a prominent role in the negotiations and planning prior to the invasion and is suitably dressed for the leader of the first attack. Over his bullet-proof armour he wears a jinbaori (surcoat), and from his back there flies a flag bearing his mon (badge), which is identical to that used by his commander-in-chief Toyotomi Hideyoshi (3). Similar flags are worn by his samurai on the backs of their armour. The ashigaru (footsoldiers) have the badge on their simple helmets. They also wear plain suits of armour over short-sleeved shirts to help them in the summer heat. The Japanese protective costume is however very sophisticated when compared with the almost total lack of protection provided for the Korean foot soldiers. Their stiffened felt hats are the only defence they have against the Japanese swords. Otherwise they are dressed in plain cloth jackets and trousers.

The only proper Korean armour is seen on the Korean officers, who wear heavy coats inside of which are leather plates, reinforced here and there with metal studs. Like their iron helmets these armours are very Chinese in appearance. The fierce resistance is under the leadership of Chŏng Pal (4), commander of Pusan, who is dressed in his distinctive black armour and is fighting under his personal standard carried by a foot soldier (5). Even this attendant to the general is very lightly armed. The plate is based on an oil painting hanging in the museum of the Ch’ungyŏlsa Shrine in Tongnae, where the defenders of Pusan are commemorated.