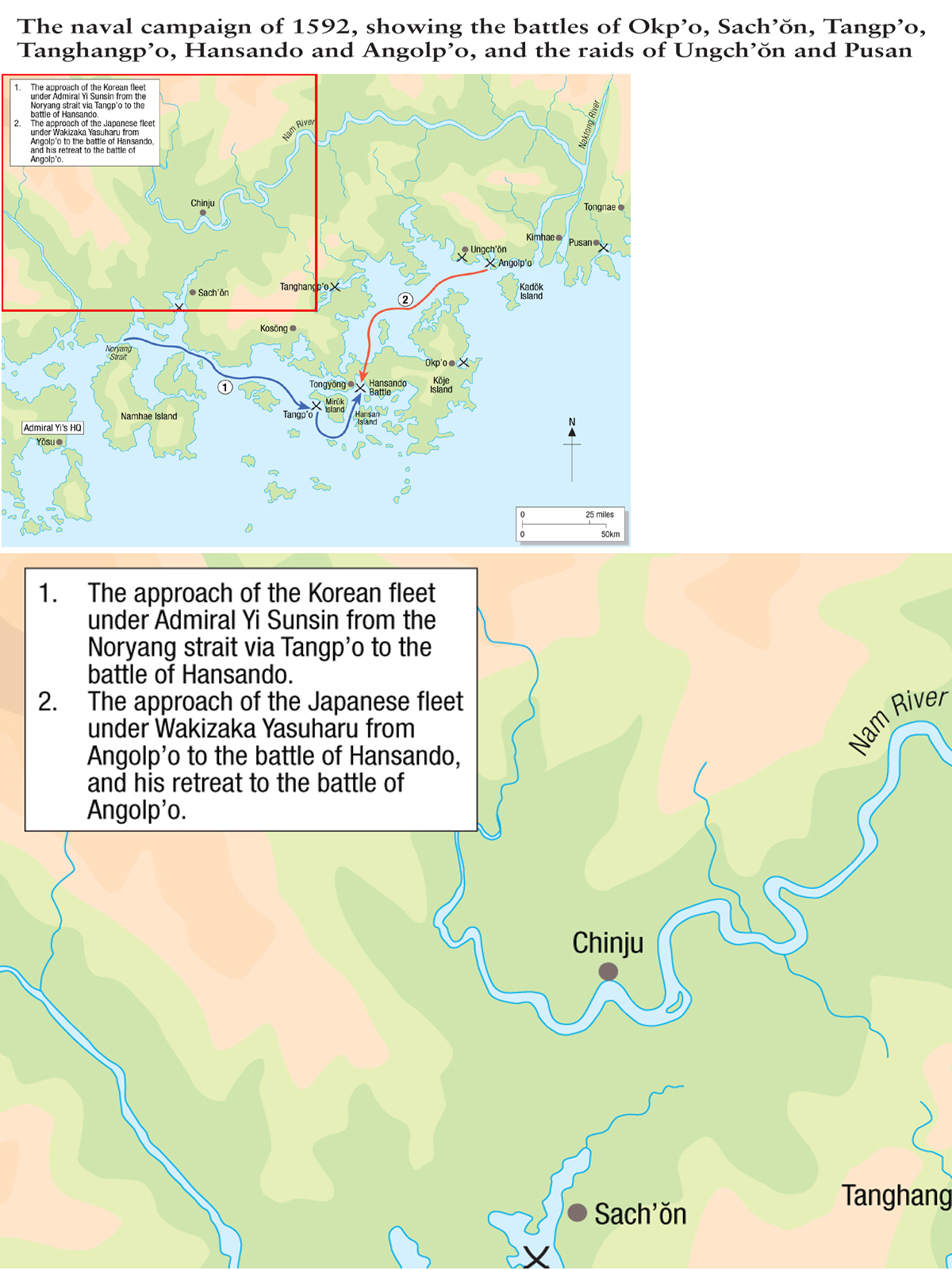

When Korea began to hit back at the Japanese the first successes were achieved at sea. Korea’s first victory of the invasion was the battle of Okp’o, a naval battle fought by Admiral Yi Sunsin off the east coast of Kŏje Island. As with so many of Yi’s operations, we have a full and detailed account in his own words written as a memorial to court. ‘Yi, Your Majesty’s humble subject, Commander of Chŏlla Left Naval Station,’ he begins, ‘memorializes the throne on the slaughter of the enemy.’ Having sent a message to Right Commander Yi Ŏk-ki to follow him, Yi set sail under cover of darkness at 2.00am at the head of 24 p’anoksŏn, 15 smaller fighting vessels, and 46 other boats. The fleet travelled for the whole of that day, entering the waters of Kyŏngsang Province at sunset, where he anchored for the night.

At dawn two days later, the fleet rounded the south coast of Kŏje Island and headed towards Kadŏk Island, where Japanese ships had been seen gathering, but while they were on their way Yi’s scouting vessels announced the discovery of 50 Japanese ships lying off the harbour of Okp’o on the eastern coast of Kŏje. As with most of these encounters, it is by no means clear who the Japanese units actually were, but their purpose was clear. Having no opposing armies to fight they were carrying out their mission to pacify Kyŏngsang by looting and burning the nearby port like their wakō ancestors. At that point the Japanese saw the Korean warships through the smoke that rose above the mountain crests, and ran about in great confusion, trying to regain their boats and man their oars. The fleet lifted anchor, but hugged the shore rather than heading for the open sea. Yi’s ships encircled the fleeing Japanese and bombarded them with cannon balls, wooden arrows and fire arrows. The Japanese returned their fire with harquebuses and bows, but the Korean tactic of attacking from a distance did not allow them any opportunity to board. They threw their stores overboard and jumped into the water to swim to the shore, while the survivors scattered over the rocky cliffs. A girl captive of the Japanese became an eyewitness to the battle of Okp’o:

Cannon balls and long arrows poured down like hail on the Japanese vessels from our ships. Those who were struck by the missiles fell dead, bathed in blood, while others rolled on deck with wild shrieks or jumped into the water to climb up to the hills. At that time I remained motionless with fear in the bottom of the boat for long hours, so I did not know what was happening in the outside world.

Resisting the temptation to send parties ashore to mop up survivors, Yi pulled his fleet back to the open sea, and preparations were being made to spend the night when five more Japanese ships were spotted. The Korean fleet gave chase and caught up with them near the mainland at Ungch’ŏn. Deserting their ships the Japanese hurried ashore, at which the Korean ships moved in and destroyed four out of the five with cannon and fire arrows. When it grew dark Yi pulled away and spent the night at sea. Twenty-six Japanese vessels had been sunk on that first day. The following morning reports were received that more Japanese ships had been sighted to the west. The Koreans destroyed 11 out of these 13 ships. Certain articles taken from the Japanese ships greatly amused Yi, who was particularly intrigued by the Japanese habit of wearing elaborately ornamented helmets:

The red-black Japanese armour, iron helmets, horse manes, gold crowns, gold fleece, gold armour, feather dress, feather brooms, shell trumpets and many other curious things in strange shapes with rich ornaments strike onlookers with awe, like weird ghosts or strange beasts.

Not wishing to exclude King Sŏnjo from such wonders, Yi forwarded with his report ‘one armoured gun barrel and one left ear cut from a Japanese beheaded by Sin Ho, Magistrate of Nagan’.

The battle of Okp’o was fought without the loss of a single Korean ship, and caused consternation among the Japanese command when the news spread to newly conquered Seoul. At the time the stand-off at the Imjin River was still continuing, and a defeat in their rear was not what the Japanese generals wanted to hear.

Japanese invaders, shown to look very much like the wakō of old, gather outside the gate of Tongnae. (From a hanging scroll in Pusan Municipal Museum, by kind permission)

The people Yi interviewed after the Okp’o actions provided ample proof of the savagery of Japan’s pacification process along the coast of Kyŏngsang and, following his initial victory, Yi was naturally determined to take the fight to the enemy again. His original intention was to mount a major sea offensive, but on receiving a report that Japanese vessels had been sighted as far west as Sach’ŏn, which lay very near the border with Chŏlla Province, Yi realized that he had to act swiftly, because it was very likely that ground troops were advancing along the coast as well.

It appeared that many Japanese ships were moored in the bay of Sach’ŏn below a promontory on which a Japanese commander had merely set up his command post. Yi knew his arrows would not reach the Japanese on the hill, and that the ebbing tide made it most unwise for the p’anoksŏn to sail in for close-range artillery fire. It was also getting dark, but the one encouraging sign was the extreme arrogance being shown by the Japanese. If they could be persuaded to display further annoyance by chasing the Korean fleet out on to the open sea then the situation could be very different. The Korean navy therefore turned tail and appeared to flee. As if on cue hundreds of Japanese poured down from the Sach’ŏn heights and leapt into their ships for a hot pursuit. By the time they caught up with the Koreans the tide had turned, and it is at this crucial point that we first read of the use in battle of Yi Sunsin’s secret weapon. ‘Previously, foreseeing the Japanese invasion,’ he writes modestly in his report to King Sŏnjo about the battle of Sach’ŏn, ‘I had a turtle ship made. …’ It was fitted:

Han Kŭkham was defeated by Katō Kiyomasa at a large grain storehouse by the sea near Sŏngjin (modern Kimch’aek). His army was pursued afterwards, and this illustration shows Han himself being chased by a samurai intent on taking his head. The samurai wears a horō (cloak) and is swinging a grappling hook on a rope. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

… with a dragon’s head, from whose mouth we could fire our cannons, and with iron spikes on its back to pierce the enemy’s feet when they tried to board. Because it is in the shape of a turtle, our men can look out from inside, but the enemy cannot look in from outside. It moves so swiftly that it can plunge into the midst of even many hundreds of enemy vessels in any weather to attack them with cannon balls and fire throwers.

A particularly brave captain was chosen to command the turtle ship on its first outing, and he led it as the Korean navy’s vanguard when they counterattacked, firing a selection of cannon balls, wooden arrows and fire arrows into the Japanese fleet. All the Japanese ships that had followed them out of the bay were sunk or burned in spite of fierce resistance, but when the fighting was at its height a lone Japanese sharpshooter nearly changed the course of Asian history by putting a bullet through Yi’s left shoulder. The wound was not serious, and with the coming of night the Korean fleet calmly withdrew.

The turtle ship saw action for a second time at the battle of Tangp’o off the south-western coast of Mirŭk Island. Once again it was the same pattern of a Japanese squadron lying at anchor to cover the looting and burning of a town. There were 21 Japanese ships in all, and their formation was dominated by a large flagship where sat a senior Japanese commander. He is usually identified as Kurushima Michiyuki, from a branch of the great pirate family of Murakami. Whatever his identity, the interviews which Yi conducted after the victory with released Korean prisoners leave no doubt about how the man died, and include a remarkable eyewitness account by a Korean girl who had been captured by the Japanese and forced to be the commander’s mistress. ‘On the day of the battle’, she related, ‘arrows and bullets rained on the pavilion vessel where he sat. First he was hit on the brow but was unshaken, but when an arrow pierced his chest he fell down with a loud cry.’

The hail of arrows and bullets came chiefly from the turtle ship, which ‘dashed close to this pavilion vessel and broke it by shooting cannon balls from the dragon mouth, and by pouring down arrows and cannon balls from other cannon’. It was an archer on a p’anoksŏn who put an arrow into the Japanese commander, at which a Korean naval officer cut off the prestigious victim’s head with a stroke of his sword. The loss of Kurushima Michiyuki was a decisive blow to Japanese morale, and nearly all the Japanese ships were subsequently sunk or burned.

For the next two days Yi’s fleet searched the islands, beaches and straits of the complex sea lanes of Korea’s southern coast for signs of the enemy, whom they found at Tanghangp’o, a wide bay across the peninsula from Kosŏng that was entered to the north-west by a narrow gulf. Twenty-six Japanese ships lay at anchor. At the sight of the Korean ships the Japanese opened a heavy fire, so Yi’s fleet held back in a circle spearheaded by the turtle ship, which penetrated the enemy line and rammed the Japanese flagship. The other Korean ships then joined in with cannon and arrow fire, but Yi realized that if the Japanese were driven back they might escape to land, so he again tried a false retreat to draw them on. Once again the ruse worked:

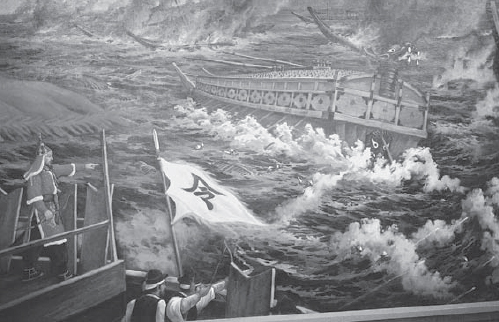

Admiral Yi Sunsin’s naval victory at the battle of Sach’ŏn was the first battle at which the turtle ship was used. In this painting in the Hansando Museum Yi is shown tending the wound he received on his arm.

The naval battle fought in Pusan Harbour by Admiral Yi Sunsin convinced the Japanese invaders of the importance of coastal defence against the Korean navy. In this diorama in Pusan Municipal Museum a turtle ship is depicted.

Then our ships suddenly enveloped the enemy craft from the four directions, attacking them from both flanks at full speed. The turtle with the Flying Squadron Chief on board rammed the enemy’s pavilion vessel once again, while wrecking it with cannon fire, and our other ships hit its brocade curtains and sails with fire arrows. Furious flames burst out and the enemy commander fell dead from an arrow hit.

A pursuit of the escaping ships began and continued until nightfall with the destruction of all the Japanese vessels except one and the taking of 43 heads. The one ship to escape was apprehended by a Korean warship the following morning and a fierce fight ensued. The Japanese captain ‘stood alone holding a long sword in his hand and fought to the last without fear’, and it was only when ten arrows had been shot into him that ‘he shouted loudly and fell, and his head was cut off’. Yi sent as proof to King Sŏnjo the ears his men had cut off from 88 heads, ‘salted and packed in a box for shipment to the court’. This was almost the same day that Konishi Yukinaga had captured P’yŏngyang, but on the seas the position of the two contending forces was totally reversed.

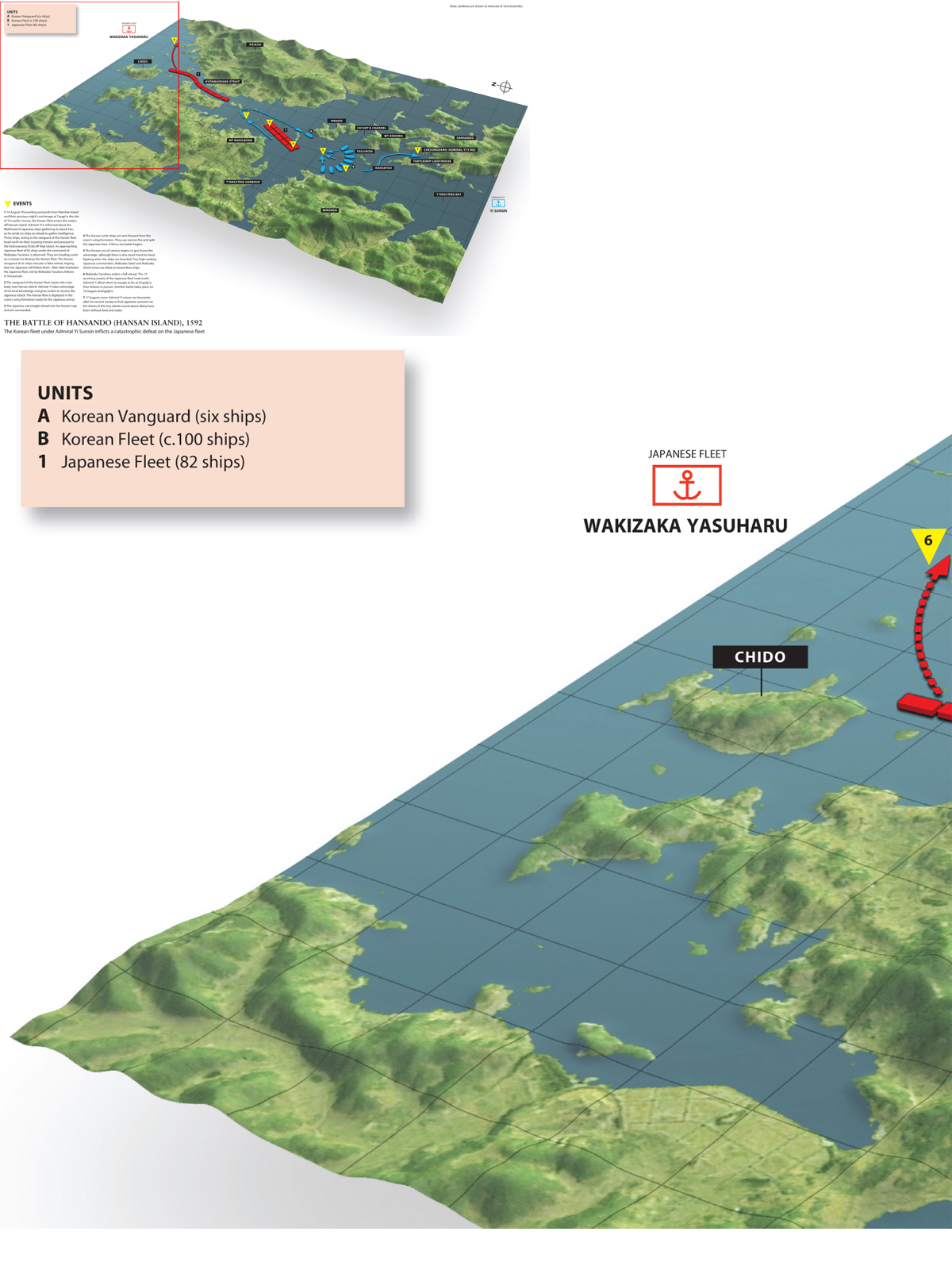

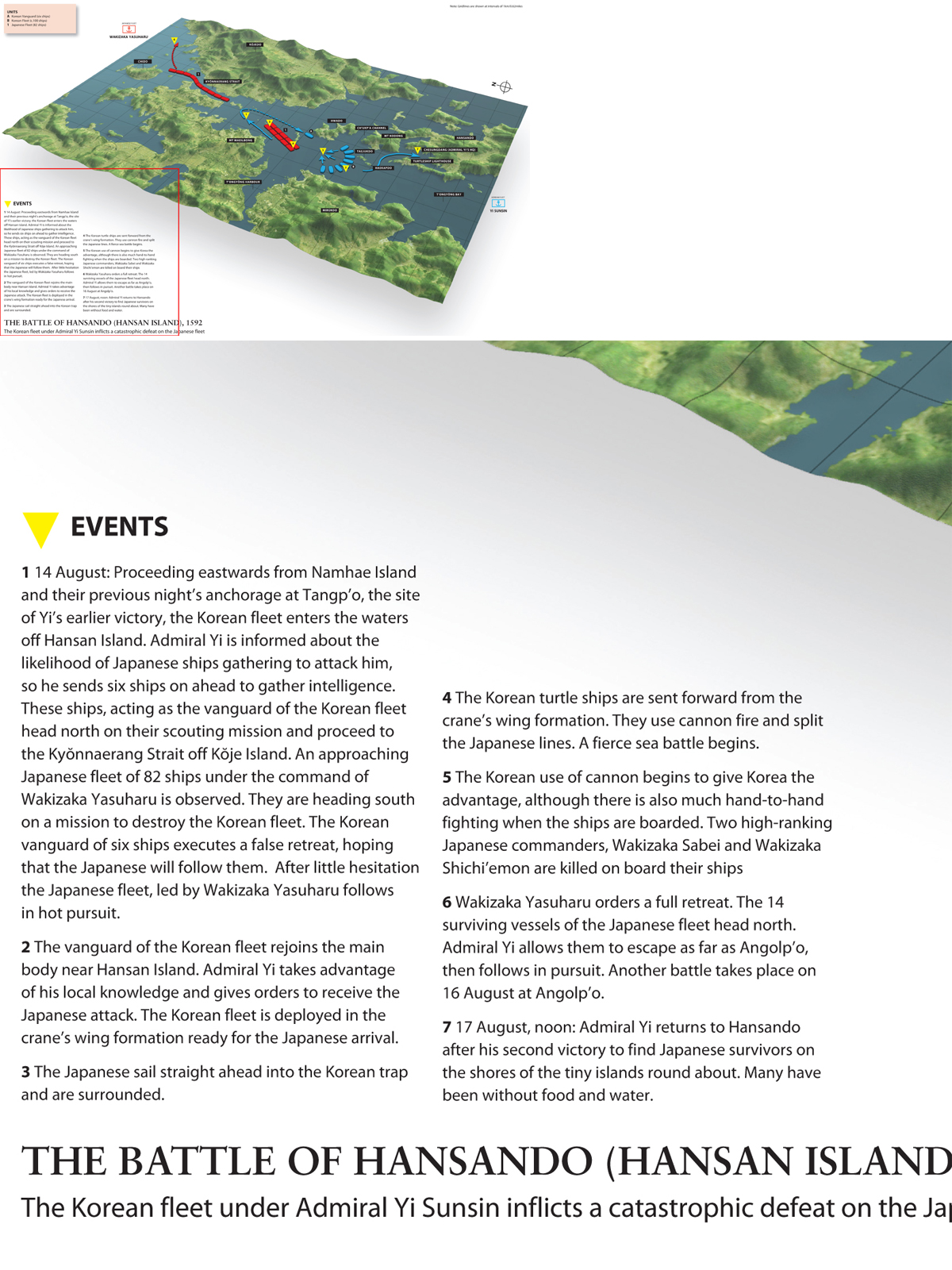

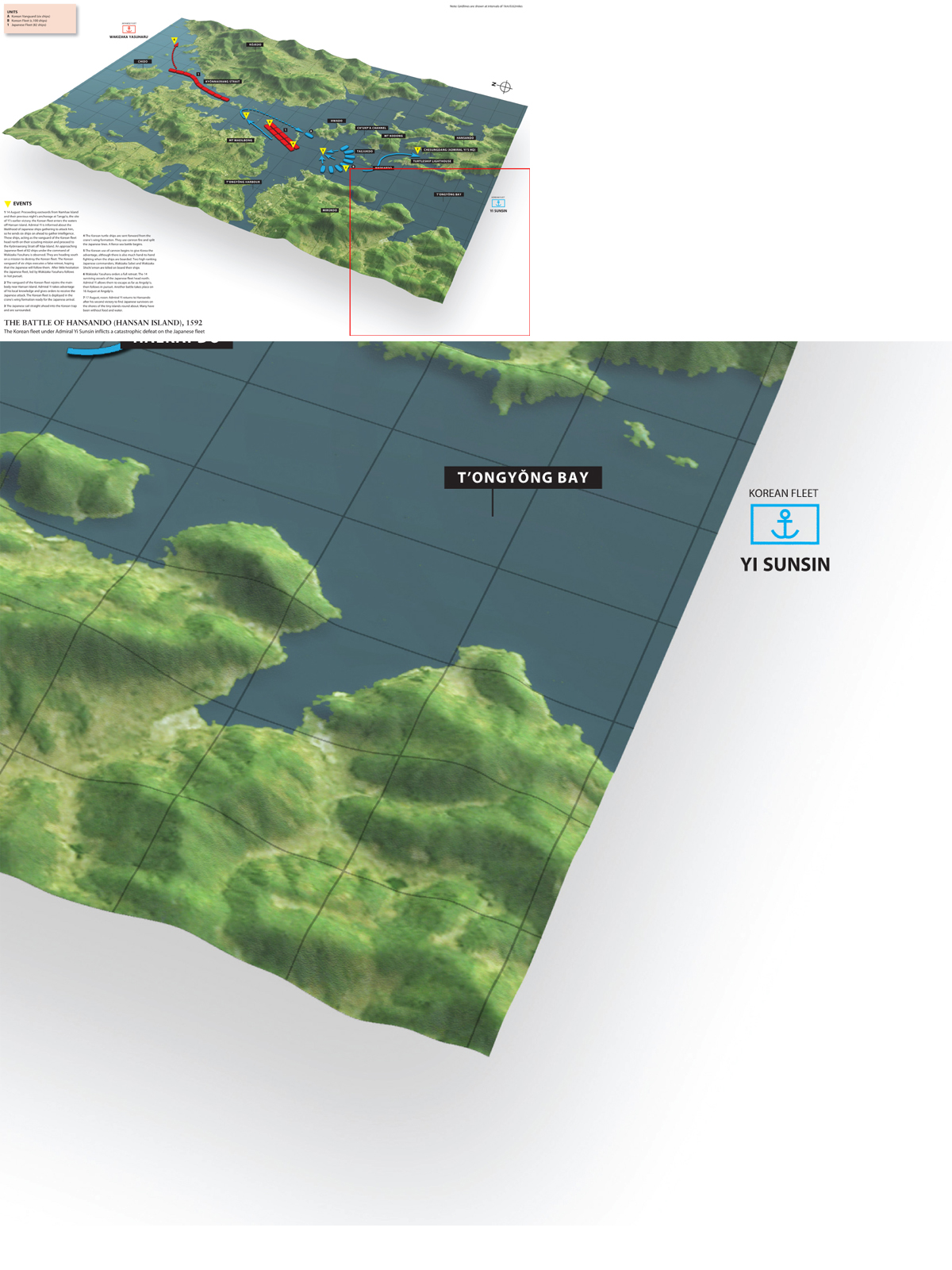

The battle of Hansando (Hansan Island) was Yi Sunsin’s greatest victory, and came about because Hideyoshi had ordered Yi’s destruction following the reversals described above. The Wakizaka ki (the chronicle of the Wakizaka family) contains the text of the order given by Hideyoshi after the debacle at Tanghangp’o to recall Wakizaka and his fellow admirals Katō Yoshiaki and Kuki Yoshitaka from land duties. Their mission was to assemble a fleet and seek out Yi Sunsin to destroy him.

Katō Yoshiaki (1563–1631), who was no relation to the other Katō, had also been one of the illustrious ‘Seven Spears of Shizugatake’. The third member of the trio, Kuki Yoshitaka (1542–1600) was the only one who had real naval experience because he had once been a pirate operating on the Pacific coast. During the early days of the Korean invasion Kuki had shared the Tsushima command with Wakizaka, but now that there was the prospect of real action such willingness to share responsibilities rapidly disappeared. Wakizaka’s fleet was ready, but neither Katō nor Kuki had enough time to assemble the number of ships they felt they needed for the operation. Being eager for personal glory, Wakizaka decided to act alone instead of waiting until they were all ready. The Wakizaka ki implies that the challenge from Admiral Yi was too pressing to consider any delay in responding, but it is more than likely that Wakizaka merely seized the opportunity to gain the personal honour of being the commander who single-handedly destroyed the Korean fleet. He therefore set sail from Angolp’o without his colleagues but with a fleet of 82 ships, including 36 large and 24 medium-sized vessels.

While Morimoto Hidetora was fighting in north-eastern Korea under Katō Kiyomasa’s command he received an arrow through his left elbow. Unperturbed, he asked a colleague to withdraw the arrow, and then galloped off anew against the enemy. This print by Kuniyoshi captures his Zen-like detachment from the pain of the wound and his resulting composure.

The ensuing struggle takes its name from the island of Hansan near to which it was fought, so the battle, which was both the Salamis and the Trafalgar of Korea, is usually called the battle of Hansando, although Japanese sources usually refer to it by another local geographical feature and call it the battle of Kyŏnnaeryang. Like Okp’o, the overall action included a follow-up operation, which is called by both sides the battle of Angolp’o. This latter engagement was fought against the joint commands of Katō and Kuki, who had by then sailed to join Wakizaka.

A turtle ship appears in this painting of the battle of Okp’o in the Ok’po Memorial Museum on Kŏje Island, even though the famous vessel did not make an appearance until the battle of Sach’ŏn.

Yi begins his report to King Sŏnjo with his assessment of the situation prior to the battle. Japanese ships still controlled the sea area between Pusan and the islands of Kadŏk and Kŏje, but had not ventured any farther west since the Tanghangp’o operation. Yet there was a worrying development on land. Yi had heard that Japanese troops had captured Kŭmsan. This meant that they were poised to make their first inroads into Chŏlla Province from the north, and up to that time Yi’s homeland of Chŏlla had been the only province still free of invaders. As naval support along the coast of Chŏlla would be vital to the Japanese advance, Yi decided on a large-scale search and destroy operation against the Japanese fleet that he confidently expected to find.

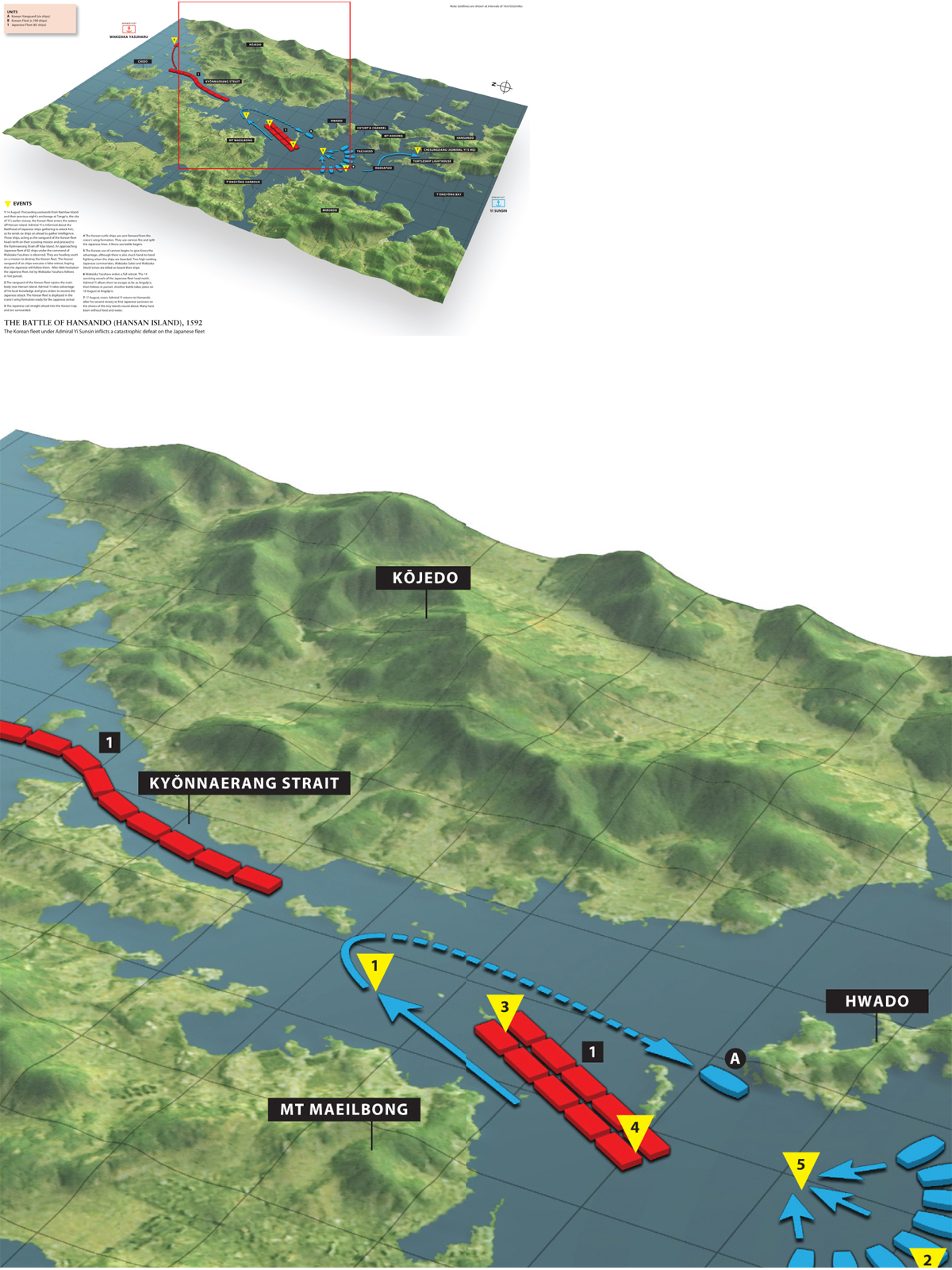

The combined fleets of the Chŏlla stations made rendezvous with Wŏn Kyun in the straits of Noryang off Namhae Island. Unfortunately no Korean records exist of the total numbers of the combined Korean fleets, but Japanese accounts suggest that it was probably around 100 ships. The following day they continued eastwards in the face of a hostile gale, and anchored off Tangp’o, the site of their previous victory, where they took on water. On seeing them a local man came running down to the beach with the news that a large Japanese fleet had been spotted nearby. The Japanese ships had sailed south-west into the narrow straits of Kyŏnnaeryang that divided Kŏje Island from the mainland and had anchored there for the night. Contact was made early the following morning when Yi’s fleet headed for the straits and counted 82 enemy vessels.

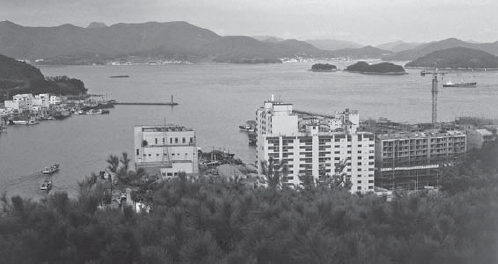

Nowadays one can stand next to the statue of Admiral Yi Sunsin on top of the hill that overlooks the port of Tongyŏng and look out across this bay where the whole of the battle of Hansando took place. To the south lies the island of Mirŭk, and to the south-east, framing the horizon of the bay, is Hansan Island itself, with several islets dotted about before it. Yi’s strategy was determined by the fact that the channel of Kyŏnnaeryang was narrow and strewn with sunken rocks, so it was not only difficult to fight in the bay for fear the Korean ships might collide with one another but provided the likelihood that the Japanese would escape to land. Yi therefore decided to try his well-rehearsed manoeuvre of a false retreat to lure the Japanese out to the south-west, where a wide expanse of sea fringed by several uninhabited islands would provide an ideal location for a sea battle.

The bait was taken, and from the north-east came Yi’s vanguard of six p’anoksŏn, beating down the straits of Kyŏnnaeryang with Wakizaka Yasuharu’s entire fleet in hot pursuit. When the Japanese were well clear of the rocky strait and out into the bay before Hansan Island they found Yi’s main body waiting for them. Here the Korean ships had spread out into a semicircular formation which Yi’s report calls a ‘crane’s wing’. The Wakizaka ki tells this part of the story as follows: ‘The guard ships passed through the middle of the strait and out into a wide area. We took to our oars, at which they spread out their ships like a winnowing fan, drew our ships on and enveloped them.’

By the time of the battle of Hansando the number of turtle ships appears to have grown to at least three, because references to them in Yi’s account clearly indicate a plural, and the Japanese account noted below counts three. With the turtles acting as the vanguard once again, the Korean fleet rowed towards the focal point of their crane’s-wing formation.

‘Then I roared “Charge!”’, writes Yi, ‘Our ships dashed forward with the roar of cannon breaking two or three of the enemy vessels into pieces’. The fight now became a bloody free-for-all, the Korean ships trying initially to keep their chosen victims at a distance in order to bombard the Japanese without the risk of a boarding party being sent against them. Much hand-to-hand fighting took place, but Yi allowed this only if the Japanese vessel was already crippled. Thus we read that ‘Left Flying Squadron Chief [a turtle boat captain] Yi Kinam captured one enemy vessel and cut off seven Japanese heads’, and a certain Chŏng Un, captain from Nokdo, ‘holed and destroyed two large enemy pavilion vessels with cannon fire and burned them completely by attacks in cooperation with other ships, cut off three Japanese heads, and rescued two Korean prisoners of war.’ The greatest glory, however, fell to two individuals:

Sunch’ŏn magistrate Kwōn Chun, forgetting all about himself, penetrated the enemy position first, breaking and capturing one large enemy pavilion vessel, and beheading ten Japanese warriors including the Commander, and bringing ˘ back a Korean prisoner of war. Kwangyang Magistrate ŎYŏngtam also dashed forward, breaking and capturing one large pavilion vessel. He hit the enemy Commander with an arrow, and brought him back to my ship, but before interrogation, he fell dead without speaking, so I ordered his head to be cut off.

The view looking from beside the monument to Admiral Yi Sunsin above the town of T’ongyŏng towards the island of Hansan. The battle of Hansando was fought within this area of sea.

A detail showing a turtle ship from a diorama depicting the battle of Hansando in the War Memorial Museum, Seoul.

The ‘commanders’ in the above paragraph probably indicates the captains of the individual ships concerned, but is it known that two people related to the overall commander Wakizaka Yasuharu were killed at Hansando, and the Wakizaka ki gives their names as Wakizaka Sabei and Watanabe Shichi’emon. Yasuharu himself had a very narrow escape:

However, as Yasuharu was on board a fast ship with many oars he attacked and withdrew freely to safety. Arrows struck against his armour but he was unafraid even though there were ten dead for every one living and the enemy ships were attacking all the more fiercely. As it was being repeatedly attacked by fire arrows, Yasuharu’s fast ship was finally made to withdraw …

Unlike Wakizaka, one ship’s captain could not face the dishonour of withdrawal: ‘A man called Manabe Samanosuke was a ship’s captain that day, and the ship he was on was set on fire. This tormented him, and saying that he could not face meeting the other samurai in the army again, committed suicide and died.’

The Wakizaka ki also adds some detail about the Korean attacks, mentioning that the Japanese fleet was bombarded with metal-cased fire bombs shot from mortars similar to those used in Korean sieges. These weapons would probably have been fired from the open p’anoksŏn rather than from the confined space of a turtle ship.

The destruction of Wakizaka’s fleet was almost total. Hardly a single ship escaped, and ‘countless numbers of Japanese were hit by arrows and fell dead into the water’, but not all were killed, because ‘… about four hundred exhausted Japanese finding no way to escape, deserted their boats and fled ashore’. The victorious Koreans, similarly exhausted, withdrew for the night.

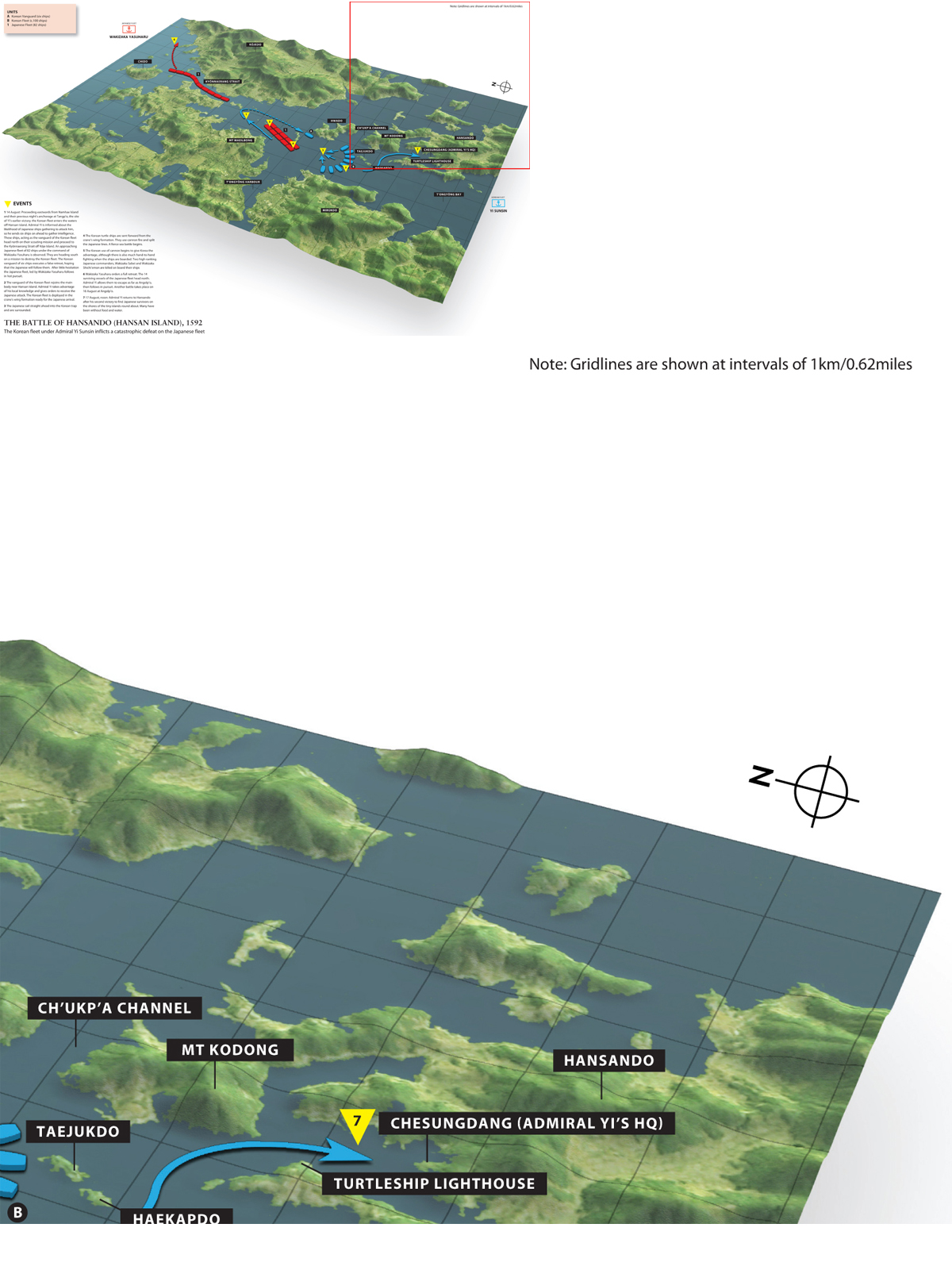

Thus ended the first phase of the most severe defeat to be suffered by a Japanese force in the entire Korean campaign, but the battle of Hansando had a sequel, because the two colleagues whom Wakizaka had left behind had hurried after him to secure their share of the glory. Leaving Pusan on the day of the battle of Hansando, they were apprised of the disaster that same evening. One chronicle tells it rather differently, and reads ‘The two men Kuki Yoshitaka and Katō Yoshiaki heard tell of the distinguished service performed by Wakizaka Yasuharu’, but whatever their motivation, their fleet reached only as far as the port of Angolp’o to which Wakizaka had withdrawn in defeat. Hindered by an unfavourable wind, Yi Sunsin had to wait one full day before pursuing Wakizaka and coming to grips with Kuki and Katō at the battle of Angolp’o.

A view from Hansan Island showing the lighthouse built in the shape of a turtle ship. The main action of the battle of Hansando took place beyond the rock on which the lighthouse was built as a memorial.

Yi Sunsin headed for the harbour to make a reconnaissance in force. Sailing forwards in the crane’s-wing formation, with Wŏn Kyun’s ships following closely behind, Yi found 42 Japanese ships lying at anchor with the protection of nearby land and shallow waters around. An attempt at a false retreat produced no response – the experience of Hansando had been enough to kill that trick stone dead – so Yi changed tactics and arranged for a relay of ships to row in, fire at the Japanese and then withdraw, so that a rolling bombardment was kept up. Yi’s report notes that this was indeed successful, and that almost all the Japanese ‘pirates’, as he perceptively calls them, on the larger vessels were killed or wounded, while many were seen escaping to land. This indicated further danger, because there was every likelihood that the Japanese would take their revenge on the Korean villagers living nearby, so, when only a few Japanese ships were left undamaged, Yi called his fleet off and pulled out to sea to rest for the night. On returning the following morning the surviving Japanese had escaped by ship, leaving the local inhabitants untouched. The report continues:

We looked over the battleground of the day before, and found that the escaped Japanese had cremated their dead in 12 heaps. There were charred bones and severed hands and legs scattered on the ground, and blood was spattered everywhere, turning the land and sea red …

From the Japanese side the chronicle Kōrai Funa Senki gives a concise account of what happened at Angolp’o which tallies with Yi’s report on most points of detail, and includes in its description the only specific mention in a Japanese chronicle of the turtle ships:

However, on the 9th day from the Hour of the Dragon [8.00am], 58 large enemy ships and about 50 small ships came and attacked. Among the large ships were three blind ships [i.e. turtle ships], covered in iron, firing cannons, fire arrows, large (wooden) arrows and so on until the Hour of the Cock [6.00pm].

The same account also adds the interesting information that Kuki Yoshitaka was commanding the fleet from the huge warship, built originally for Hideyoshi, which had become the flagship of the Japanese navy on the outbreak of the Korean War. It was called the Nihon-maru (the equivalent of ‘HMS Japan’), of which more details appear in the Shima gunki: ‘A three-storey castle was raised up, with a brocade curtain arranged in three layers, and on top was a “Mount Hōrai”, and on top of the mountain was a prayer offered to the Ise Shrine.’

The decorative ‘Mount Hōrai’ (Hōrai is the treasure mountain of Chinese mythology) was a Shintō device with rice heaped up on three sides, and adorned with various sacred objects, so that when ‘they blew the conch and advanced upon the Chinamen the sight gave the impression that the Mount Hōrai was floating’. The Koreans were clearly unintimidated by this mystical addition to the Japanese armoury and opened up on the Nihon-maru with everything they possessed:

However, when the fire arrows came flying, we were ready and pulled the charred embers into the sea with ropes, and the ship was not touched. They fired from near at hand with half-bows too, which went through the threefold curtain as far as the second fold, but ended up being stopped at the final layer. They then moved in at close range and when they fired the cannons they destroyed the central side of the Nihon-maru for three feet in each direction, but the carpenters had been ordered to prepare for this in advance, and promptly made repairs to keep out the seawater.

The battle of Angolp’o was fought on 16 August, and it was noon of the 17th when Yi’s fleet sailed back into the bay in front of Hansan Island that had been the scene of his most complete triumph. There they saw the Japanese who had escaped to that island sitting dazed on the shore, lame and having gone hungry for many days. There were 400 of them, although the Japanese records claim only half this number. By now Yi was receiving routed the invaders. reports of Japanese ground troops advancing into Chŏlla Province from the Kŭmsan area, so he withdrew to his base at Yoŭsu. The Japanese fugitives then escaped by making rafts out of broken ships’ timbers and trees, but the escape of the Japanese prisoners was only a minor blot on an otherwise complete victory. The Korean prime minister, Yu Sŏngnyong, heartened by a further piece of good news on the naval front, pondered on the significance of Hansando in his book Chingbirok: ‘Japan’s original strategy was to combine her ground and naval forces and advance into the western provinces. However, one of her arms was cut off by this single operation. Although Konishi Yukinaga has occupied P’yŏngyang, he can hardly dare to advance because he is isolated.’

At the battle of Ich’i, Kwŏn Yul placed a detached unit as an ambush for the Japanese and routed the invaders.