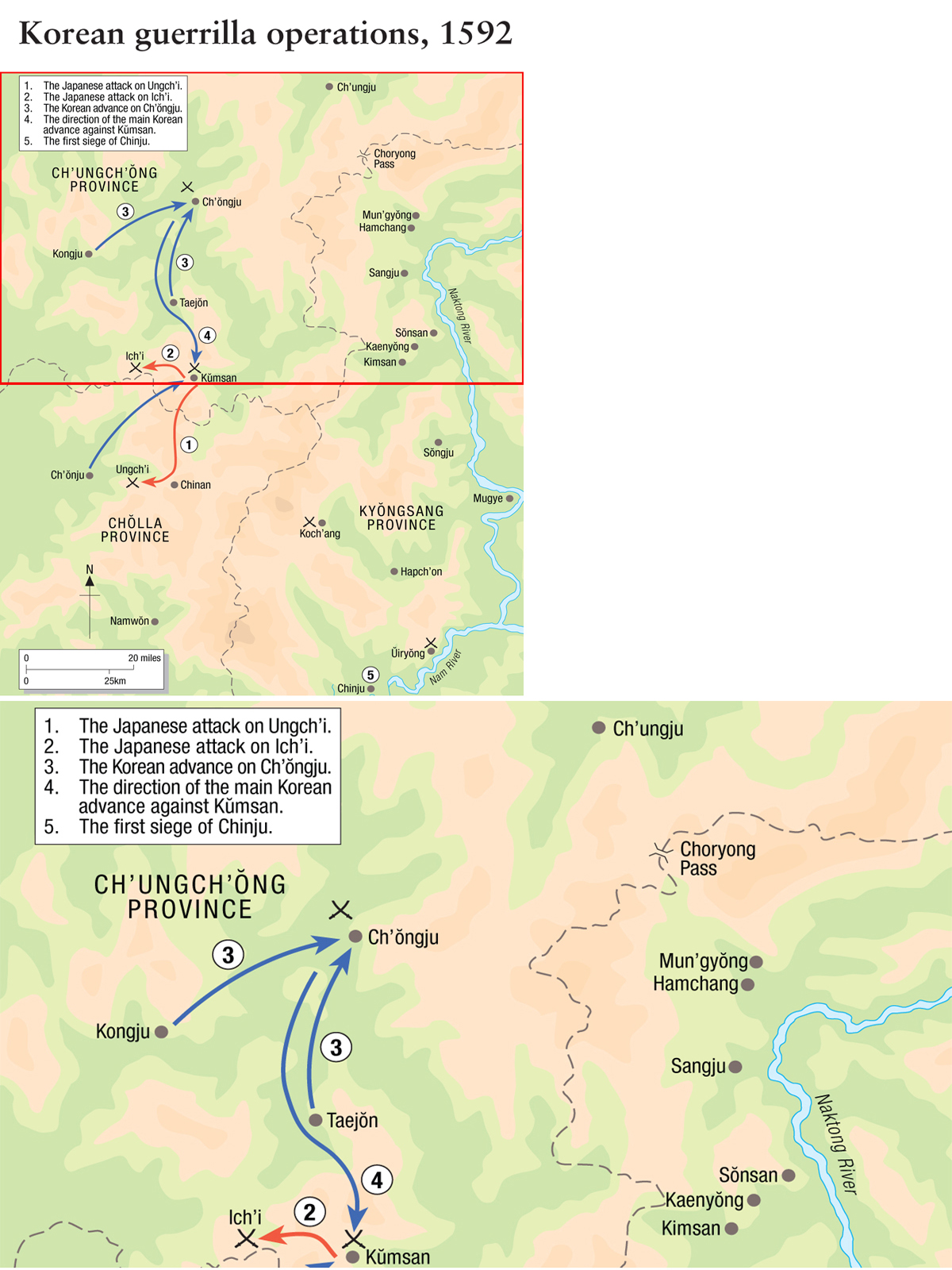

The second element in the defeat of the Japanese was the Korean resistance on land mounted by three types of warriors. The first were regular troops who had rallied after the initial disasters. Some of their new leaders were serving officers who had received rapid promotion following the death of a general. The second were volunteer armies that went under the general heading of the Uibyŏng or ‘Righteous Armies’. The final group were the monk soldiers, armies of whom were established in every province very early in the campaign. Theirs was largely a guerrilla war. The activities carried out ranged from straightforward battles and sieges through night raids to the support functions of transporting supplies and building walls. Their operations covered every area where Japanese forces might be challenged, from the Naktong Delta in the south to the Yalu River in the north. For the seven months prior to the arrival of Ming forces in January 1593, an estimated 22,200 irregulars shouldered the burden of resistance together with 84,500 regular soldiers, and made a considerable contribution to the war effort.

Kwak Chae-u as depicted in a painting in the Memorial Museum at Ŭiryŏng. His guerrilla operations gave Korea its first victory of the war.

The first guerrilla leader was Kwak Chae-u, who provided resistance while the regular Korean army still lay shattered. He is remembered today as a romantic and mysterious patriotic hero, appearing from nowhere to defeat the Japanese. Kwak’s guerrillas began to prey on the Japanese river boats ferrying newly landed supplies upstream and won an early victory at the battle of Ŭiryŏng. As well as disrupting the Japanese advance, the attacks on the line of the Naktong also provided a similar defence by land to that which Admiral Yi was providing at sea against an incursion westwards into Chŏlla Province.

Within days of Kwak Chae-u raising his volunteer army in Kyŏngsang Province, we also read of a similar force being created over in Chŏlla by a certain Ko Kyŏngmyŏng (1533–92). Ko was 60 years old and a yangban (aristocratic scholar) who succeeded in forming an army of 6,000 men, but the brevity of his career, which ended with his death in battle, has prevented him from attaining the legendary status of Kwak Chae-u. His military skills were considerable, but he lacked Kwak’s appreciation of the need for caution in the face of the Japanese war machine, as shown by his death at the first battle of Kūmsan.

Japanese soldiers beg for mercy as they are overwhelmed by the guerrillas commanded by Kwak Chae-u as depicted on the bas-relief on the side of the plinth of his statue in Taegu.

Kobayakawa Takakage’s Sixth Division occupied Kŭmsan, which today is one of the main centres in Korea for the growing of ginseng. It was somewhat isolated, as it lay to the west of the string of communications forts between Pusan and Seoul. With Ko at their head the united Chŏlla army moved in to attack Kŭmsan on 16 August. Resistance was fierce, and the regular troops under Kwak Yŏng on the flank of the Chŏlla army began to waver, so Ko pulled the whole army back. The following day they attacked again, led by 800 men from the Righteous Army, but the Japanese recalled the effect their tactics had produced the previous day and concentrated their attacks on the regular troops. This pressure had the desired effect, and a furious Ko Kyŏngmyŏng saw Kwak Yŏng’s troops falling back all round his own gallant band. With a shout to the fleeing Kwak Yŏng of, ‘To a defeated general death is the only choice!’ he plunged into the enemy and was killed along with his two sons.

The Righteous Army of Ch’ungch’ŏng Province and their leader Cho Hŏn, in company with an army of warrior monks, carried out the next phase of the war. The initiative for inviting Korea’s monastic community to join in the struggle against the Japanese seems to have come originally from King Sŏnjo himself. While in exile in Ŭiju the king summoned the monk Hyujŭng and appointed him national leader of all the monk soldiers in Korea. Hyujŏng dispatched a manifesto calling upon monks throughout the land to take arms against the Japanese. ‘Alas, the way of heaven is no more’, it began. ‘The destiny of the land is on the decline. In defiance of heaven and reason the cruel foe had the temerity to cross the sea aboard a thousand ships.’ The samurai were ‘poisonous devils’, and ‘as virulent as snakes or fierce animals’. He reminded his listeners that one of the Five Secular Precepts, a series of teachings combining Confucianism and Buddhism had been to face battle without retreating. Hyujŏng then called on the monks to ‘put on the armour of mercy of Bodhisattvas, hold in hand the treasured sword to fell the devil, wield the lightning bolt of the Eight Deities, and come forward.’

The result of the manifesto was the recruitment of 8,000 monks over the next few months. Some were undoubtedly motivated by patriotism, but others saw it as an opportunity to raise the social status of Buddhist monks, who had suffered from a royal obsession with Confucianism. Although their numbers were small compared with the civilian volunteers their units were cohesive and clearly associated with a particular leader and a particular province. Unfortunately, however, they were not immune from jealousy towards the Righteous Armies, which was to lead to trouble on more than one occasion when a joint operation was being planned.

This memorial to the Korean warrior monks who fought during the Japanese invasion is to be found in Seoul.

In Ch’ungch’ŏng Province the driving force in the monk resistance was Abbot Yŭnggyu, who enthusiastically promoted an anti-Japanese movement among his clerical brothers. The first operations in which the monks engaged were guerrilla activities similar to those of their volunteer colleagues, until a major action in September against the Japanese garrison of Ch’ŏngju thrust them into the limelight. Ch’ŏngju was an important transport centre for the Japanese army and also housed an important granary. It was, however, lightly garrisoned, and the Korean volunteers knew it.

On 6 September, Cho Hŏn’s Righteous Army of 1,100, together with 1,500 warrior monks and a rearguard of 500, advanced on Ch’ŏngju. The monks attacked the north and east gates, while the volunteers assaulted the west gate. The Japanese quickly drove them off, so Cho Hŏn took up a position on a hill to the west for a second attempt. During the night they lit fires and set up many flags to give the impression of a large host. Fooled completely, the small Japanese garrison planned an immediate evacuation, and the next day Cho Hŏn and his men walked into the castle in triumph. Unfortunately, within days of this considerable Korean victory an argument developed among the leaders over who was to take the credit for it. Different reports were submitted from different viewpoints and relationships deteriorated even further. The tragic result was that a Korean army was at last in a position to take the fight to the enemy, but internal squabbles were threatening to destroy any chance of success.

Thus it was that when a Korean army marched south from Ch’ŏngju to attack Kŭmsan, once again it was a force already doomed by division. The regulars under Yun Sŏngak refused to participate, so the monks and volunteers decided to go ahead without them, but even they were determined to mount two operations independent of each other. The haughty Cho Hŏn planned to launch his attack before the monks, in spite of the fact that the monastic army had now been greatly strengthened by the welcome arrival of another contingent. Cho’s incredible plans faced opposition even from within his own depleted ranks, because Ku˘msan was not a lightly garrisoned fort like Ch’ŏngju, but a well defended salient held by 10,000 battle-hardened men under Kobayakawa Takakage. Yun Sŏngak was so opposed to the idea that he went to the length of imprisoning close relatives of the volunteers to dissuade them from fighting, and even the well-respected Kwŏn Yul lent his weight to the arguments against Cho Hŏn’s foolhardy plans.

In this dramatic depiction of guerrilla activity a Japanese patrol is ambushed and pelted with arrows and stones. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

On 22 September, Cho Hŏn led an army of only 700 volunteer soldiers against 10,000 of the toughest samurai in Korea at the second battle of Kŭmsan. Kobayakawa Takakage soon realized that this isolated force was all that was being sent against him. As night fell the Japanese encircled them and exterminated the entire army, including the reckless Cho Hŏn. Seeing the destruction of his comrade’s army, the monk Yŏnggyu felt that he had to follow where Cho Hŏn had led, so over the next three days the monk armies took part in a third battle of Kŭmsan. The result was the same as at the second battle – total annihilation.

A lavish yet very moving memorial shrine called the ‘Shrine of the Seven Hundred’ now stands on the site of the battles of Kŭmsan. It honours both monk and volunteer alike, and inside one of the halls two dramatic paintings recall the glory of Ch’ŏngju and the disaster of Kŭmsan. Everywhere there is the memory of self-sacrifice and the exhortation for patriotic Koreans to emulate these heroes of old, but nowhere is there any account of the rivalry, pride and selfishness that snatched defeat out of the hands of victory.

Although Cho Hŏn’s recklessness lost the battle, it had helped to win the campaign. The fact that Kŭmsan had now suffered three attacks made the Japanese command question whether the Kŭmsan Salient was worth retaining, so Kobayakawa’s Sixth Division were pulled back. To the guerrillas this was all that mattered, and this example of what could be achieved encouraged them to carry on with their own campaigns. Another guerrilla leader, Pak Chin, determined to recapture Kyŏngju with a secret weapon. According to Chingbirok something was fired over the walls of Kyŏngju and rolled across the courtyard. Not knowing what it was, the ‘robbers’, as he calls the Japanese garrison, rushed over to examine it. At that moment the object suddenly exploded, sending fragments of iron far and wide and causing over 30 casualties. Such was the alarm it caused that Kyŏngju was evacuated, and the ‘robbers’ pulled back to the safety of the coastal wajō at Sŏsaengp’o.

The pressure from Korean guerrilla attacks forced Ukita Hideie, the commander of all the Japanese forces, to send reinforcements to Kyŏngsang from Seoul, and towards the end of October the decision was made to capture the Koreans’ strongest point in western Kyŏngsang: the town of Chinju, which lay on the Nam River. Chinju was a fortified town with a long high wall that touched the river on its southern side. Between Chinju and the line of the Naktong was Kwak Chae-u’s guerrilla territory, and up to that moment in the war the garrison of this strong fortress had never seen a Japanese soldier. Ukita’s generals reasoned that if Chinju could be taken then the recaptured castles would fall back into Japanese hands, the guerrillas would lose rear support, and a new road to Chŏlla Province would finally be opened.

The castle of Chinju was under the command of Kim Shimin, who led a garrison of 3,800 men. Kim was a fine general, and was not willing to provide the Japanese with their customary experience of a weak Korean castle defence. Instead he had acquired 170 newly forged Korean harquebuses made to quality standards equivalent to the Japanese ones, and had trained his men in their use. Chinju was the first occasion when these weapons were tried in battle. Kim also had many cannon and a supply of mortars and bombs of the same type that had caused such devastation at Kyŏngju.

The Japanese army crossed the Nam River and approached Chinju from three sides, surprising some Korean stragglers. The Taikōki tells us that a certain Jirōza’emon ‘took the first head and raised it aloft. The other five men also attacked the enemy army and took some excellent heads.’ When the Japanese reached the walls of Chinju, Kim’s troops hit back at them with everything in their possession – harquebus balls, bullets, exploding bombs and heavy stones. It was not the reaction Hosokawa and his men had been expecting, so, changing their plans, they made shields out of bamboo and under the cover of massed volleys of harquebus fire approached close to the walls where long scaling ladders were set up. As the samurai scrambled up the ladders the defenders ignored the bullets and bombarded them with rocks, smashing many ladders to pieces. Meanwhile delayed-action bombs and lumps of stone fell into the mass of soldiers awaiting their turn to fight for the special honour of being first into the castle. The Taikōki gives a vivid account of one such endeavour:

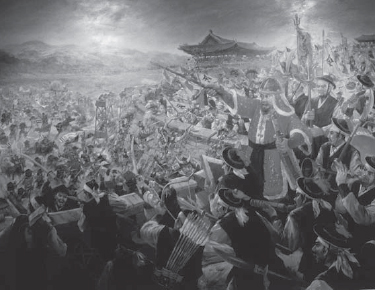

The fall of Ch’ŏngju to the Righteous Army of Cho Hŏn and the warrior monks under Yŏnggyu is shown here on a painting displayed in the ‘Shrine of the Seven Hundred’ in Kŭmsan. This was one of the greatest achievements by the irregular forces of Korea.

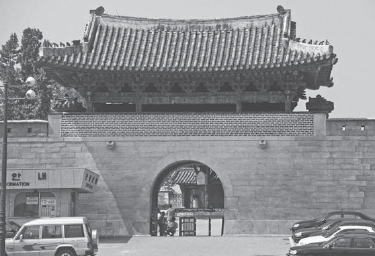

The restored eastern gate of Chinju, the scene of two fierce sieges with very different outcomes.

Kim Shimin drives back the Japanese attack during the first siege of Chinju (From a painting in the War Memorial Museum, Seoul, by kind permission)

As we try to become ichiban nori [first to climb in] they climbed up as in a swarm. Because of this the ladders almost broke, and comrades fell down from their climb, so they could not use the ladders. Hosokawa Tadaoki’s brother Sadaoki was one such, accompanied by foot soldiers on ladders on his right and left, and strictly ordered ‘Until I have personally climbed into the castle this ladder is for one person to climb. If anyone else climbs I will take his head!’ then he climbed. Because of this the ladder did not break and he got up, and the men who saw him were loud in his praise. Consequently, before very long he placed his hands on the wall, but when he tried to make his entry from within the castle, spears and naginata were thrust at him to try to make him fall, and lamentably he fell to the bottom of the moat.

None of the Japanese army was to earn the accolade of ichiban nori that day, although many tried, and as the forward troops clawed at Chinju’s battlements Japanese labourers behind them were bullied into hurriedly erecting crude siege towers from which harquebuses could shoot down into the courtyard.

For three days this bitter battle, which was unlike anything seen up to that point in the Korean campaign, deposited heaps of Japanese dead in the ditch of Chinju Castle. On the night of 11 November a guerrilla army under Kwak Chae-u arrived to witness the spectacle. It was a pitifully small band to be a relieving force, so Kwak ordered his men to light five pine torches each and hold them aloft as they blew on conch shells and raised a war cry at the tops of their voices. The arrival of a further 500 guerrillas from another direction added to the illusion of a mighty host, then they too were joined by 2,500 more. But the Japanese were not to be diverted from their main objective. Disregarding this newly arrived threat for a short while Hosokawa flung his men into a final attempt to take the castle by storm as he led attacks on the northern and eastern gates during the night of 12 November.

While fighting beside his men on the north gate Commander Kim Shimin received a mortal wound from a bullet in the left of his forehead and fell unconscious to the ground. Seeing this, the Japanese diverted all their troops to the northern side of Chinju’s ramparts, trying to gain a handhold on top of the walls, but from the ground below the Koreans swept the walls with arrows and bullets and drove them off. The Chinju garrison were perilously short of ammunition, but just then a Korean detachment arrived by boat up the Nam River bringing welcome supplies of weapons, powder and ball, an event that greatly heartened the garrison. By now all of the Japanese troops had been committed to the assault. They had no rearguard, and were deep inside enemy territory, so to their great chagrin (and the fury of Hideyoshi when he heard about it), the Japanese generals decided to abandon the siege of Chinju. It was a deep embarrassment. The Korean revival – the second element in the resistance against Japan – had produced results as inspiring as Yi Sunsin’s naval victories.

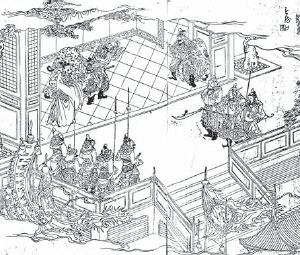

The rapidity of the Japanese advance and the enormity of the Korean collapse initially made the Ming suspicious that the Koreans were in league with the invaders. At the conference depicted here Yu Sŏngnyong convinced the Chinese otherwise. From Ehŏn Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.