Taking an overview of the Korean campaign, while the naval victories and the guerrilla raids were very important in preventing the Japanese from advancing, it was the intervention of Ming China that threw the entire operation into reverse. From the time of the Chinese recapture of P’yŏngyang in February 1593 the Japanese army’s movements were those of retreat.

The Chinese intervention may have been long in coming, but it was formidable in its eventual execution. The genuine desire by the Chinese to help Korea had always been somewhat outweighed by their outrage at Japan’s challenge to the Ming’s authority on continental East Asia. That affront alone required a military response, but the continuing Ningxia situation had meant that it was much delayed. The first move by the Chinese was not carried out until late August 1592 and comes across as little more than a token gesture because an army of only 3,000 troops was ordered to retake P’yŏngyang. Their commander Zu Chengxun nevertheless felt very confident that he had sufficient resources to fulfil his task. He was after all an experienced general who had fought the Mongols and the Jurchens and had nothing but contempt for the Japanese.

The exact layout of P’yŏngyang’s defences will be described later in the account of the successful operation in 1593; for now it is sufficient to note that Zu Chengxun’s attempt proved to be a very short-lived affair. Boasting that he had once defeated 100,000 Jurchens with 3,000 horsemen, the supremely confident general took advantage of a heavy rainstorm to attack P’yŏngyang at dawn on 23 August. He seems to have taken Konishi Yukinaga completely by surprise because Yoshino Jingoza’emon, whose Chōsen ki (Korea Diary) provides a valuable eyewitness account, writes of ‘the enemy entering in secret’. Most of the Japanese army did not have time to put on their armour and just seized whatever weapons lay to hand as the Chinese flung themselves against the walls. Matsuura Shigenobu was but one of the First Division’s commanders who became personally engaged in combat, receiving an arrow through his leg.

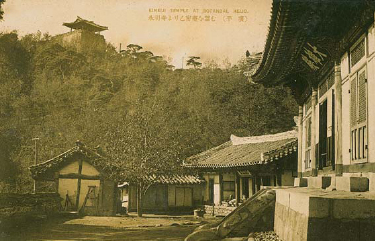

The temple of Yŏngmyŏngsa lay at the foot of Mount Moranbong, and was to experience some very fierce action during the siege of P’yŏngyang.

The Japanese defenders of P’yŏngyang, as depicted on a Chinese painted screen in the Hizen-Nagoya Castle Museum. Their weapons include harquebuses and naginata.

Zu Chengxun’s success in entering P’yŏngyang by storm was to prove his undoing. When the Japanese realized that they outnumbered the attacking army by six to one they allowed the Liaodong troops to spread freely into the narrow streets of the walled city. Soon what had been a hammer blow action against one section of the wall rapidly diffused into hundreds of ineffective skirmishes by small groups of isolated Chinese soldiers who could be picked off at will by the Japanese harquebuses. A retreat was called, so the survivors were allowed to flood out of the opened gates. Once they were in the open and hindered by the deep mud the mounted samurai cut them down in their dozens. The Chinese mobile corps commander, Shi Ru, was killed, and Zu Chengxun barely escaped with his life.

The defeat of the first Chinese expeditionary force produced mixed reactions among the Japanese commanders. There was certainly an initial feeling of elation at having beaten off a Ming army, and as reinforcements from Japan were expected to arrive any day this dramatic confirmation of Japan’s superiority added to their readiness to press on for the Yalu River. But the days soon grew into months and no reinforcements arrived. News was received that guerrillas were harassing Japanese communications by land while Admiral Yi was completely severing them by sea, and the feeling also grew that the Chinese would return in far greater numbers. It was a concern shared at the highest level of the Japanese command, and Konishi Yukinaga journeyed to Seoul for a conference with Ukita Hideie. The gloomy conclusion they reached was that when P’yŏngyang was attacked again it might fall because it was now so isolated.

The decisive Ming advance came with the turning of the year. The crushing of the Ningxia revolt finally gave the Chinese the opportunity they needed to convince the Japanese that their fears of the mighty Ming were well grounded. Li Rusong, the hero of Ningxia, was made commander of the Korean expeditionary force, and set off to relieve P’yŏngyang with a recent siege success under his belt. Li was a much more patient character than his predecessor, and showed that he was capable of learning from Zu Chengxun’s mistakes. His first decision was not to risk another attack in summer but to wait until the bitter Korean winter had frozen the ground solid so that his artillery train could be moved with ease. During the autumn his subordinate commanders received training at Shanhaiguan on the Great Wall, and eventually 30,000 men and three months’ supply of food had been assembled in Liaodong. The target number was 75,000, although the Ming hierarchy believed that 100,000 were actually needed if the task was to be accomplished quickly. With only 75,000, it was feared, Li Rusong would need a year to drive the Japanese out, but less than half that number had been assembled. They were nevertheless well supplied with weapons and winter clothing, and enough silver had been released from the Ming defence budget to provide 200 more cannon.

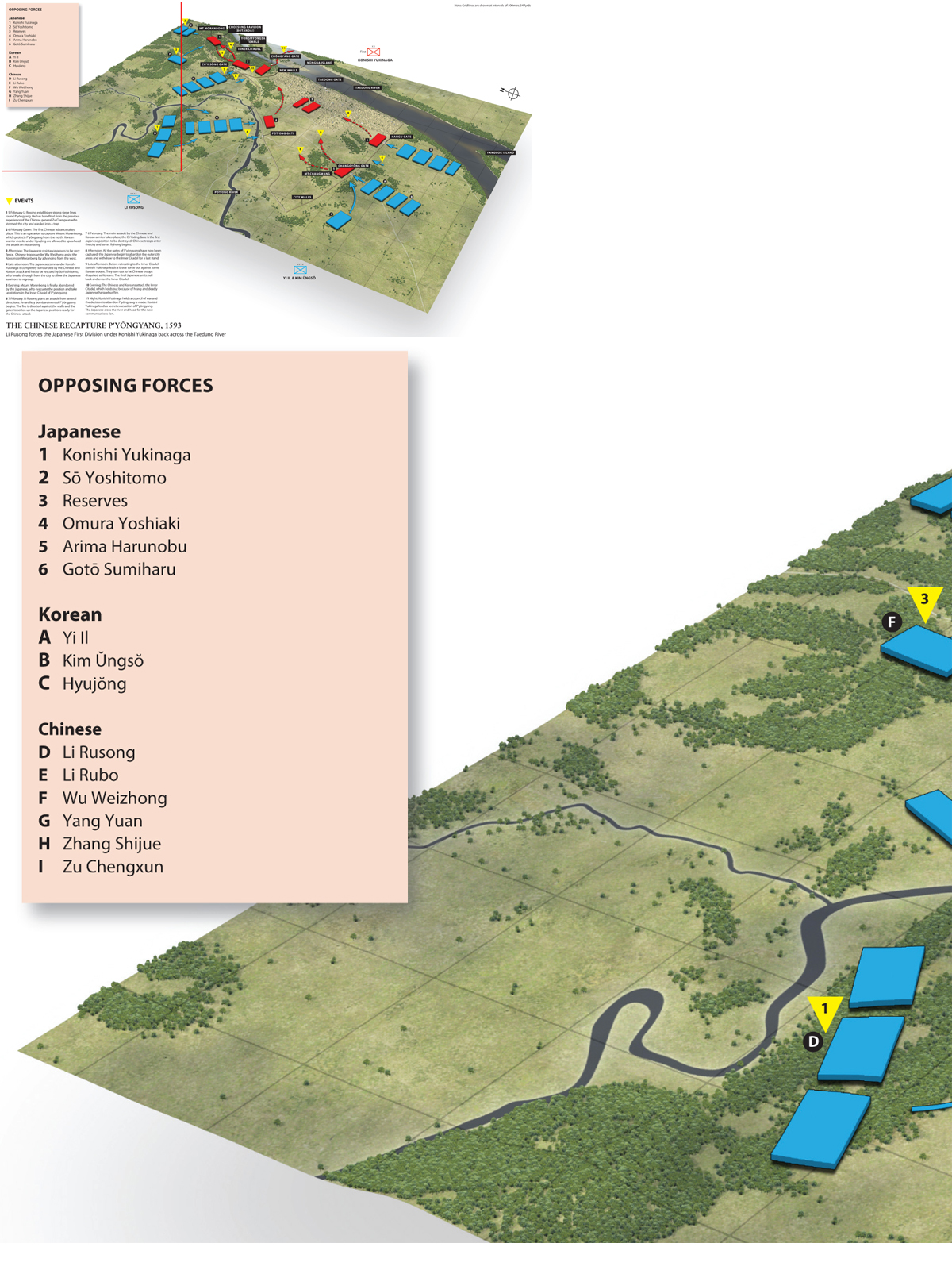

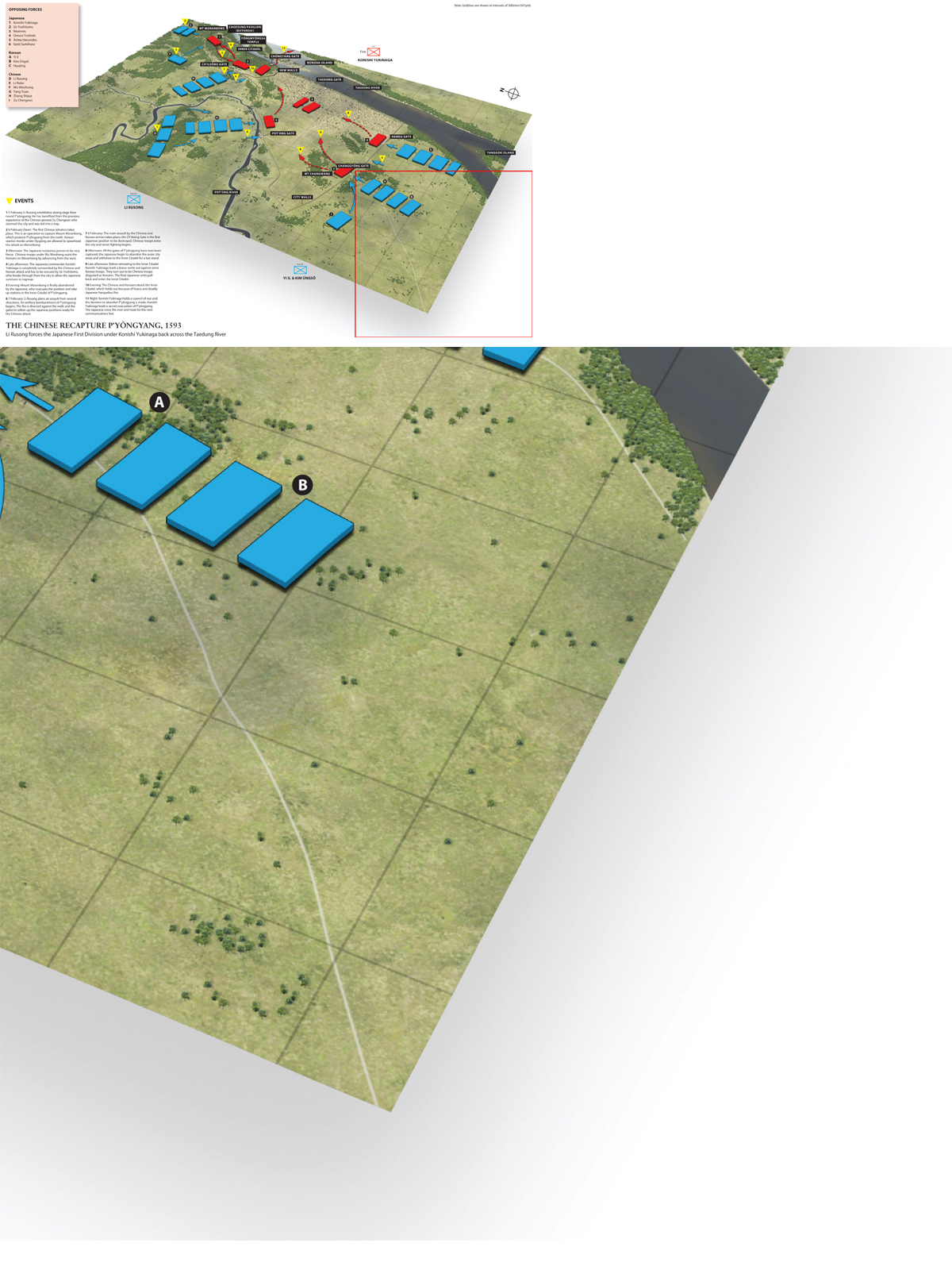

On 5 January 1593, Wu Weizhong led an advance guard across the Yalu River. It consisted of 3,000 men, and two more battalions of 2,000 each followed them. They waited for Li Rusong with the main body at Ŭiju, where King Sŏnjo of Korea greeted the Chinese as saviours. He was accompanied by his prime minister, Yu Sŏngnyong, who provided maps of the area and brought the Chinese up to date on the existing military situation. The Chinese army was then arranged into three divisions. Li Rubo, Li Rusong’s younger brother, commanded the left wing, Yang Yuan commanded the centre while Zhang Shijue commanded the right. A rapid advance from Ŭiju followed that left their horses sweating heavily in spite of the cold.

Unlike his predecessor, Li Rusong made good use of advanced scouts and soon flushed out a Japanese advance party, from whom five were killed and three captured. Another skirmish followed in a forest to the north of P’yŏngyang until, on 5 February 1593, Li Rusong drew up his ranks outside the city. Early next morning Konishi Yukinaga offered to talk terms with Li Rubo within P’yŏngyang, but the cautious Li Rubo feared a trap and refused. That night his camp was attacked by a Japanese sortie but his alert guards warned him and the Japanese were driven back to the accompaniment of fire arrows. A false retreat was ordered, and some Japanese were foolish enough to follow the Chinese lead and became ambushed themselves.

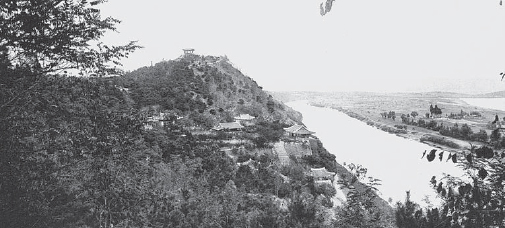

The task facing the Chinese was a considerable one, because P’yŏngyang enjoyed a naturally strong position and was defended by some of Korea’s more formidable walls. They enclosed an area that was largely flat apart from Mount Changwang (40m) in the south-west of the walled city. The Taedong River protected the city to the east and had acted as a moat when the Japanese attacked in 1592, but in January 1593 the Taedong was of less importance than the narrower Pot’ong River that flowed on the other side of the city and provided defence against an attack from the north-west. The city walls of P’yŏngyang formed a crude elongated triangle lying between the Pot’ong and Taedong rivers, within which were six gates. The Changgyŏng and Taedong gates gave access to the river on the east. The Ch’ilsŏng (Seven Stars) Gate allowed access to the north-west. From there the wall continued south and touched the Pot’ong River on its western side where lay the Pot’ong Gate. In the south wall were the Chŏngyang Gate and the Hangu Gate. Leaving the Taedong River gates lightly defended, each of the four landward main gates of the city was defended by 2,000 Japanese troops. There are no records of which gates were assigned to which commanders, but we do know that P’yŏngyang was defended solely by the First Division who had landed so triumphantly in Pusan seven months earlier. Most of the remainder of the 15,000 soldiers under Konishi Yukinaga’s overall command were within the walls and ready to be moved wherever they were needed, although a small number may have been stationed on Nŭngna Island in the middle of the Taedong River as a rearguard to cover the crossing points in case of a retreat. All Korean civilians in the city had been evacuated.

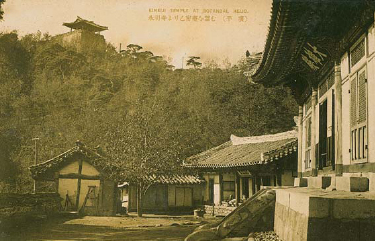

A view of P’yŏngyang during the early 20th century, showing Mount Moranbong and the Taedong River.

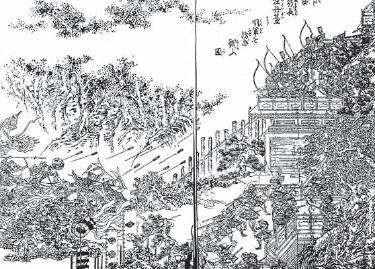

The first fighting during the Chinese recapture of P’yōngyang was an attempt to control Mount Moranbong, where Konishi Yukinaga established his command post. It lay just to the north of the city proper and dominated the river. Here we see Konishi Yukinaga defending the so-called Tree Peony Pavilion on its summit. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

One vital sector in P’yŏngyang’s defences, however, lay just to the north of the city proper. This was Mount Moranbong, which dominated the area and was physically included in the city’s defensive perimeter by means of walls that ran up its slopes and were furnished with fortified gates. In peacetime Mount Moranbong was a popular place from which to enjoy the attractive view of the river over the tree peonies on its slopes. The picturesquely named Choesung Pavilion (Tree Peony Pavilion or Botandai in the Japanese chronicles) on its summit at 70m above sea level provided the command post for Konishi Yukinaga and 2,000 bodyguard troops, and was to see some of the fiercest fighting of the forthcoming battle. A Buddhist temple, the Yŏngmyŏngsa, lay on the mountain’s southern side.

Sō Yoshitomo leads a desperate sortie out of one of the gates in the walls surrounding Moranbong to allow Konishi Yukinaga to escape to the inner citadel. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

The Japanese had also constructed an inner defensive citadel within the tight triangle of the walls in the north-eastern section of the city, but because of the shortage of time and a deep distrust of Korean military architecture that the experience of the past months had done little to dispel, this was done by creating Japanese-style earthworks rather than building more stone walls. The embankments were reinforced with trenches and palisades that would allow a clear field of fire for the defenders and would also provide absorbency for the cannon balls that were likely to be fired against them by the Chinese field artillery. Clever use was also made of discarded swords and daggers, because Yu Sŏngnyong noted that ‘The spears and swords that the Japanese had set up on the battlements, pointed at the Chinese soldiers, looked like the needles of a porcupine.’

Li Rusong’s 43,000-strong army had now been swollen by an additional 10,000 Korean troops under Yi Il and Kim Ŭngsŏ, some regulars, some volunteers and 5,000 warrior monks. Korean records also tell of the presence of over 40,000 Jurchens under the banner of Nurhaci. If this is correct it demonstrates how ineffective Katō Kiyomasa’s north-eastern campaign had been, but Chinese accounts do not mention any Jurchens and instead record considerable disappointment that only half the number of troops they wanted had been assembled. Li Rusong was also concerned about the lack of discipline among his troops, and rigorously weeded out 400 men whom he considered to be too old or too weak to fight. On a brighter note supplies continued to arrive, so Li could count on enough food for four months. His artillery train was also most impressive. Li Rusong appreciated that the Japanese had superiority in hand-held firearms, but dismissed them with the words, ‘Japanese weapons have a range of a few hundred paces, while my great cannon have a range of five to six li [2.4km]. How can we not be victorious?’

Li Rusong set up his headquarters on high ground to the west of the Pot’ong River with 9,000 men, and deployed 10,000 Chinese troops under Zhang Shijue against the Ch’ilsŏng Gate and 11,000 under Yang Yuan against the Pot’ong Gate. A further 10,000 Chinese under Li Rubo faced the Hangu Gate, while 8,000 Koreans under Yi Il and Kim Ŭngsŏ were ordered to attack the Chŏngyang Gate. Li’s overall plan was to surround P’yŏngyang with his artillery and open fire on to the city from four directions. This would create chaos among the defenders and provide a cloud of smoke under which the Chinese could advance, with the initial objective being the strategic Mount Moranbong. His cannon were therefore distributed evenly round the city and carefully guarded. To ensure that discipline was enforced Li gave orders that anyone fleeing from the attack should be beheaded. Once the city was entered the rule was that ordinary Japanese soldiers were to be killed outright while senior officers should be captured alive. On being driven out of the city any fleeing Japanese who did not then drown in the Taedong River were to be cut down without any mercy.

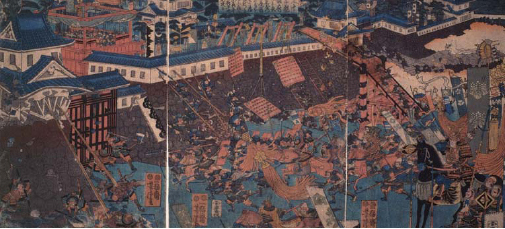

Here we see the Chinese army breaking into the Ch’ilsŏng Gate with the Japanese defenders fleeing back inside. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

After a botched attempt to assassinate Konishi Yukinaga by inviting him to peace talks and laying an ambush, the conventional assault began. Three thousand Korean warrior monks, whose fighting qualities were greatly respected by Li Rusong, were allocated to attack Konishi Yukinaga on Mount Moranbong. The Korean monk army was under the command of Hyujŏng, the leader who had first called the religious contingent to arms and, on 6 February 1593, he led his men up the steep northern slopes in the face of fierce harquebus fire to begin the battle for P’yŏngyang. There were hundreds of casualties, but the monks persevered, and received support rather late in the day from a Chinese unit under Wu Weizhong, whose unit began scaling the western slopes. Wu Weizhong received a bullet in his chest. There was soon a real danger that Konishi Yukinaga would be isolated from his main army and be killed, but Sō Yoshitomo, who was determined to die overwhelmed by impossible odds like the noble samurai of old, led a counterattack and rescued him.

The battle for Mount Moranbong continued for two days. Matsuura Shigenobu appears to have been the last Japanese commander to leave, and on that second day Li Rusong ordered a general assault on the rest of the city. The Chinese cannon boomed out from all directions while incendiary bombs and fire arrows were loosed over the walls and set many buildings ablaze. The mountains echoed to the cannon’s roar, and even the surrounding forest caught fire. With the sound of the first cannon providing the signal to advance, the Chinese with Li Rusong at their head advanced in a probing assault to be met by a withering harquebus fire from the walls topped with sword blades, from where the Japanese thrust out long spears, dropped rocks, loosed arrows and poured boiling water. One Ming officer had his feet crushed by a falling rock. Smoke began to obscure the scene, and eyewitnesses of the fighting described how the Chinese corpses piled up so densely outside the walls that they made a ramp up which their comrades clambered.

Chinese soldiers wielding spears and halberds attack P’yŏngyang under the protection of cannon fire, as depicted on a Chinese painted screen in the Hizen-Nagoya Castle Museum

Li Rusong was so involved in the fighting for the walls that his horse was shot dead beneath him. To stiffen his men’s resolve he publicly killed a fleeing Chinese soldier and offered 5,000 ounces of silver to the first man to get over the wall. Siege ladders on wheeled carts, the famous ‘cloud ladders’ of Chinese siegecraft, helped the process along, and Luo Shangzhi from Zhejiang Province became one of the first to break in, wielding his huge halberd like an ancient Chinese war god. With such determination, and at a heavy cost in casualties, all the landward gates were taken. Yang Yuan broke through the Pot’ong Gate as a bloody street fight began. The monk survivors of the attack on Mount Moranbong and Wu Weizhong’s Chinese troops joined Zhang Shijue to fight their way in through the Ch’ilsŏng Gate where all defences had been destroyed by cannon fire. Spurred on by Li Rusong’s promises of reward, heads, armour and clothing were taken from corpses to provide the necessary evidence that the victim was a high-ranking Japanese officer.

Under intense Chinese pressure the Japanese were driven back all along the line, and the entire length of the city walls was finally evacuated for the inner citadel. The Chinese who had broken through surged forwards and caught sight of the crude defences of the makeshift Japanese castle, which drew scorn from the Ming officers. They compared the mounds of earth unfavourably with their own elegant Great Wall of China. These simple defences were more like the earthen walls thrown up by the barbarous Jurchens, but that was before these Chinese officers had experienced the volleys of Japanese bullets that were to be discharged from behind them. Yu Sŏngnyong refers to the surprise they presented to them in Chingbirok: ‘The enemy built clay walls with holes on top of their fortress, which looked like a beehive. They fired their muskets through those holes as much as they could, and as a result, a number of Chinese soldiers were wounded.’

The Chinese and Korean ranks were so tightly packed that the volleys of harquebus balls caused considerable casualties. Many retreated out of the Ch’ilsong Gate, and at some point Konishi Yukinaga bravely led his men out to break out from the inner citadel but was driven back by cannon fire. As his troops swung round they encountered what they believed were Korean soldiers. They turned out to be Chinese disguised as Koreans under the former attacker of P’yŏngyang, Zu Chengxun, a revelation that is said to have created panic.

By now the winter’s night was drawing on, and as Li Rusong had his enemy cornered he was loath to provoke any more desperate sallies, so he called off his men to rest until morning. That night Konishi Yukinaga made the decision to retreat. Under cover of darkness, the entire Japanese garrison took advantage of the frozen surface of the Taedong River, slipped out of Changgyŏng Gate and evacuated the city across Nŭnga Island without either the Chinese or Korean armies knowing anything about it. As Yoshino Jingoza’emon tells us:

There was hardly a gap between the dead bodies that filled the surroundings of Matsuyama Castle [Mount Moranbong]. Finally, when we had repulsed the enemy, they burned the food storehouses in several places, so there was now no food. On the night of the seventh day we evacuated the castle, and made our escape. Wounded men were abandoned, while those who were not wounded but simply exhausted crawled almost prostrate along the road.

Konishi Yukinaga’s retreat to Seoul took nine painful days. The first refuge for this ragged, tired, frozen and wounded army was P’ungsan, the nearest of the communications forts that lay back along the line towards Seoul, held by Otomo Yoshimune of the Third Division. But an unpleasant surprise lay in store for Konishi’s men, because to their astonishment P’ungsan had been abandoned. Patrols sent out by Otomo had reported to him that Konishi was under attack and that both fields and mountains were filled with enemy soldiers. Otomo Yoshimune’s conclusion was that Konishi had probably been defeated already by the time his scouts had ridden back. No relief march was conceivable with his tiny garrison, nor could they withstand the huge force that must be bearing down upon them, so Otomo decided to burn P’ungsan and retreat to Seoul. Yoshino puts into words the hardship this extraordinary decision caused to the wounded and frostbitten survivors of Konishi’s army:

Because it is a cold country, there is ice and deep snow, and hands and feet are burned by the snow, and this gives rise to frostbite which make them swell up. The only clothes they had were the garments worn under their armour, and even men who were normally gallant resembled scarecrows on the mountains and fields because of their fatigue, and were indistinguishable from the dead.

A diary kept by a member of the Yoshimi family adds snow-blindness to the list of afflictions from which the wounded men were suffering. These unfortunates were now faced with a further day’s march through the wind and snow to the next fort, but a samurai’s cowardice in the face of an enemy could not easily be forgiven. Otomo’s family, one of the oldest and noblest in Kyūshū, and one of the first and greatest of the Christian daimyō, was now disgraced irreparably and forever.

The fall of P’yŏngyang was the turning point in the first invasion. The retreat that Konishi Yukinaga had begun when he evacuated the city through its eastern gates was to end at Pusan a few months later with very little delay or counteroffensive. Much is made in the Japanese accounts of their rearguard victory at Pyŏkjeyek to the north of Seoul, which proved to be the biggest land battle of the war and resulted in the triumphant Li Rusong being driven back northwards in disgrace. But in spite of the heavy Chinese losses it did nothing to change the overall strategy, and the retreat from Seoul was delayed by only a few days. Pyŏkjeyek was nevertheless a numerical victory for the Japanese. In the fierce hand-to-hand fighting the razor-sharp edges of the Japanese blades cut deep into the heavy coats of the Chinese, while Japanese foot soldiers tugged mounted men from the backs of their horses using the short cross blades on their spears. Li Rusong was unhorsed in the thick of the fighting, so Li Yousheng used his own body to provide a shield for his commander, who was rescued when his brothers attacked. The brave subordinate general’s sacrifice had not been made in vain, because it enabled Li Rusong to escape from the field.

Konishi Yukinaga leads the evacuation of P’yŏngyang out of the Changgyŏng Gate and across the frozen Taedong River. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

Attention then shifted to the fortress of Haengju on a hill 13km northwest of Seoul. It overlooked the Han River and covered all approaches down to the capital. On hearing of the Chinese advance against Seoul, Chŏlla Province’s skilled general Kwŏn Yul took over this dilapidated castle which possessed steep cliffs on the river side and abrupt slopes in all other directions. Kwŏn Yul’s 2,300 men, including a monk contingent, strengthened Haengju’s fortifications with ditches and palisades and waited for the opportunity to join the Chinese attack on Seoul.

The battle of Pyŏkjeyek, of course, meant that Kwŏn Yul was waiting in vain, and having won that battle so decisively Ukita Hideie decided to make Haengju his next triumph. At dawn on 14 March, Ukita led a massive 30,000-strong Japanese army out of Seoul to crush the minor annoyance. Konishi Yukinaga and Kobayakawa Takakage are two of the famous names that took part. The attack began about 6.00am with little overall plan, just a steady advance up the steep slopes of Haengju from all directions. But the Koreans were waiting for them. Dug in behind earthworks and palisades they replied with bows, harquebuses, delayed-action mortar bombs, rocks and tree trunks. Pride of place in the Haengju armoury, however, was a substantial number of the curious armoured artillery vehicles called hwach’a (fire wagons). A hwach’a consisted of a wooden cart pushed by two men on level ground, or four on steep ground. On top of the cart was mounted one of two varieties of a honeycomb-like framework from which either 100 steel-tipped rockets or 200 thin arrows shot from gun tubes could be discharged at once. Timing was of course crucial, because a hwach’a could not be easily reloaded, but the Japanese attack at Haengju was delivered in the form of dense formations of men marching slowly up a steep slope, so conditions could hardly have been better.

Ukita Hideie, who was appointed Supreme Commander following the successful landing. He was based in Seoul and led the attack on Haengju. (From a hanging scroll in Okayama Castle, reproduced by kind permission)

Haengju is regarded, with Hansando and the first battle of Chinju, as one of the three great Korean victories of the war. In an action that had passed into legend even the women of the garrison played their part, carrying stones to the front line in their aprons and their skirts. In spite of the hail of missiles the overwhelming superiority in numbers of the Japanese forced Kwŏn Yul’s troops back onto their second line of defence, but they went no farther. Nine attacks in all were made against Haengju, and each was beaten off for a total Japanese casualty list that Korean sources claim may have reached 10,000 dead or wounded. After the battle, notes Yi Sŏngnyong in Chingbirok, ‘Kwŏn Yul ordered his soldiers to gather the dead bodies of the enemy and vent their anger by tearing them apart and hanging them on the branches of the trees.’

The result of the Haengju debacle was that within a space of less than 20 days the Japanese had gained one tremendous victory and suffered one humiliating defeat, with the inevitable result that the military effects of each cancelled the other out. The Chinese army had withdrawn, but they were expected to return, and the Korean position was stronger than ever after the engagement at Haengju. The despondent Chinese general Li Rusong resolved to return to the fray when he heard of the triumph at Haengju, and Chinese troops began to move south towards Seoul once again.

Within the capital were scenes of misery and chaos. A mere 11 months had passed since over 150,000 Japanese troops had landed in Korea. Now the best estimate of the army’s strength was 53,000 men. Death and wounds from numerous battles, sieges, frostbite, guerrilla raids and typhoid fever had taken a huge toll, and the chronicler noted how the common soldiers had suffered frostbite and snow-blindness, and one or two had even been eaten by tigers while on sentry duty.

To the background of an eerie truce, which was frequently broken by both sides, the Japanese army evacuated Seoul and headed south, its vanguard crossing the Naktong River at the end of May, and finally pulled their rearguard into the safety of Pusan in early June. The Chinese army officially liberated Seoul on 19 May. Yu Sŏngnyong described the ghastly scene in Chingbirok:

The moment I entered the castle, I counted the number of survivors among the citizens, who totalled only one out of every hundred. Yet they looked like ghosts, betraying their great sufferings from hunger and fatigue. The corpses of both men and horses were exposed under the extreme heat of the season, producing an unbearable stench which filled the streets of the city. I passed the residential districts, both public and private, only to find remnants of complete destruction. Also gone were the ancestral shrines of the royal family, the court palaces, government offices, office buildings and various schools. No trace of the old grandeur could be seen.

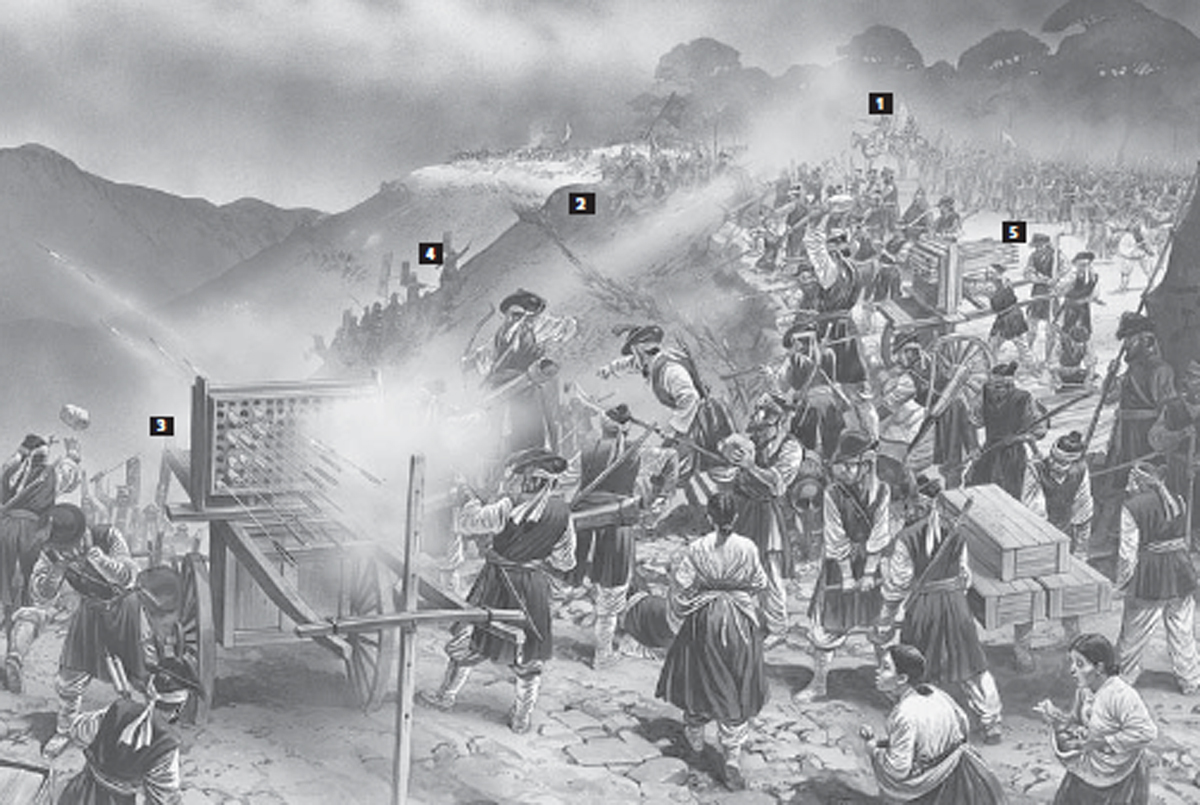

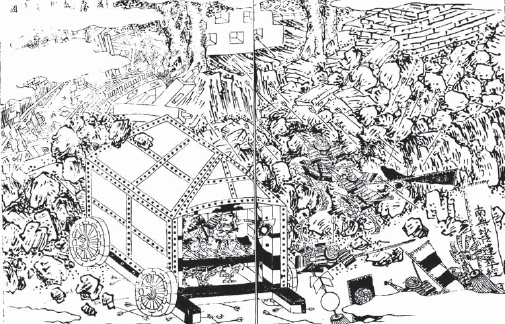

KWŎN YUL DEFENDS HAENGJU AGAINST THE JAPANESE ATTACK 1593 (pp. 64–65)

Haengju was a small sansŏng (mountain fortress) to the north of Seoul and was the site of one of the most important Korean victories during the invasion. As the Japanese retreated towards Seoul after the fall of P’yŏngyang Korea’s ablest general, Kwŏn Yul, reinforced Haengju and waited to join the Chinese advance on the capital. However, because the battle of Pyōkjeyek had stalled the Chinese advance the Japanese were newly confident. Seeing this mountain fortress in their way, Haengju came under attack from Ukita Hideie.

In this plate we see the desperate defence of Haengju, which shows good use of the mountain location and the deployment of Korean military skills at their finest. To the rear General Kwŏn Yul (1) directs the operations from on horseback accompanied by his standard-bearer. The brunt of the attack is being borne at the edge of the plateau, which has been cleared to provide a clear field of fire and reinforced with stakes and a stone wall (2). Rocks are thrown down onto the advancing Japanese, the stone missiles being brought to the defenders by women carrying the projectiles in their aprons, a famous feature of the legendary defence. Good use is also made of the hwach’a (3), the dramatic rocket-firing carts. Timing was of course crucial, and the defenders of Haengju have clearly waited until a sizeable group of Japanese are in close range. As the assault party, flying from their armour blue flags bearing the mon (badge) of Ukita Hideie (4), reach the wall the hwach’a is fired with a deafening roar, and the rockets tipped with arrowheads fly down into the midst of the Japanese. The Korean standing next to the cart covers his ears. A further supply of rockets is cautiously brought up, and in the middle of the picture we see a hwach’a being reloaded from a fresh salvo (5). Otherwise the Koreans use harquebuses, bows and arrows, swords and tridents. The successful defence of Haengju effectively neutralized the new wave of optimism that the Japanese had after Pyŏkjeyek, and it was not long before Seoul was evacuated for good. The plate is based on an oil painting in the Memorial Shrine to Kwŏn Yul and the defenders of Haengju that has been erected on the summit of the mountain overlooking the Han River to the north of Seoul.

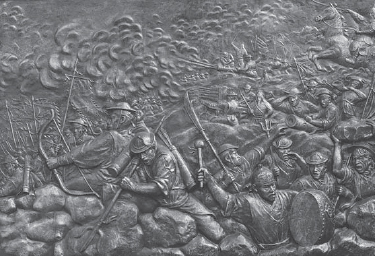

Kwŏn Yul defending Haengju, from the bas-relief on the monument on the site of the battle. The hwach’a (rocket wagons) and the women bringing stones in their aprons are well illustrated.

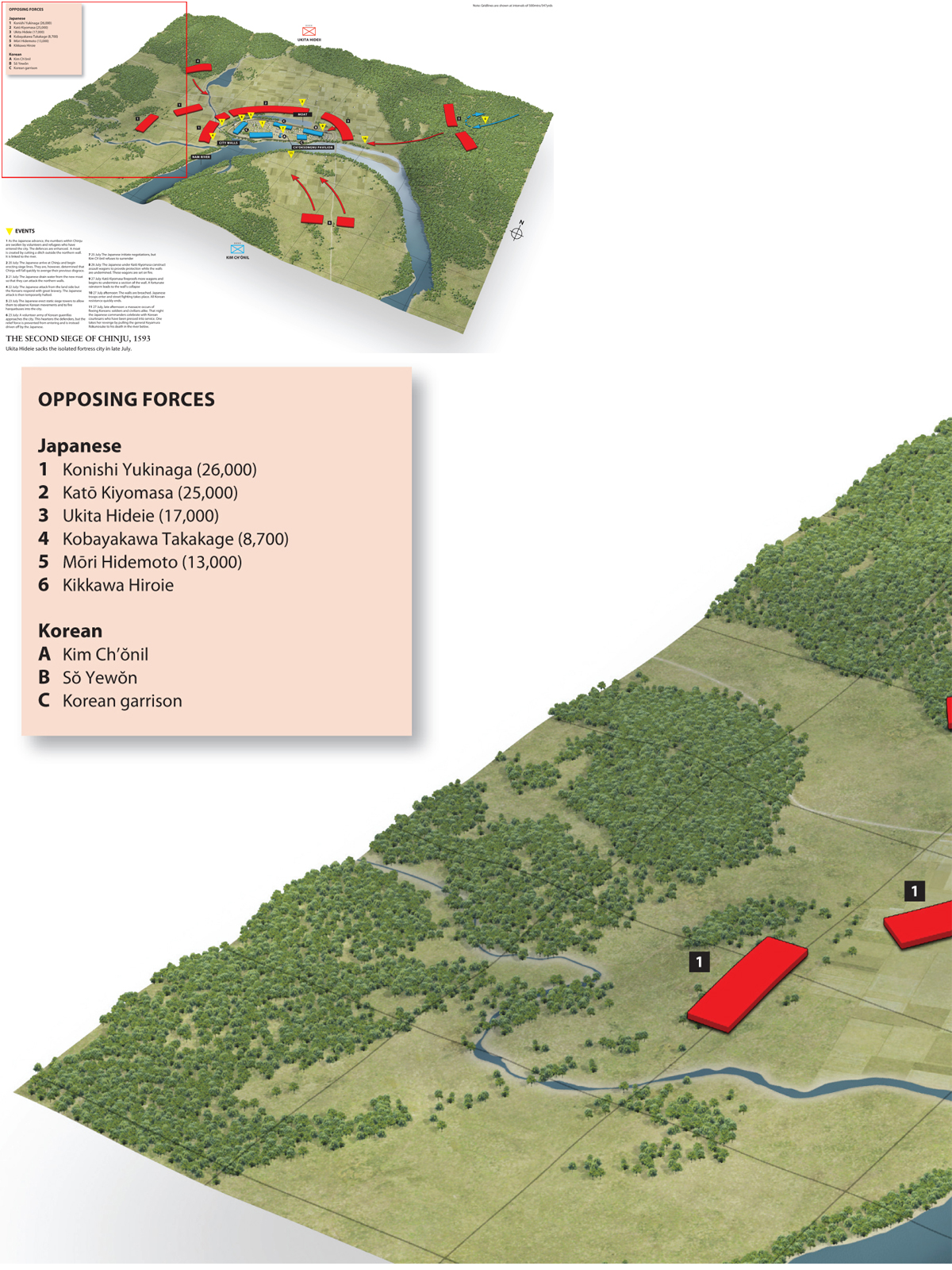

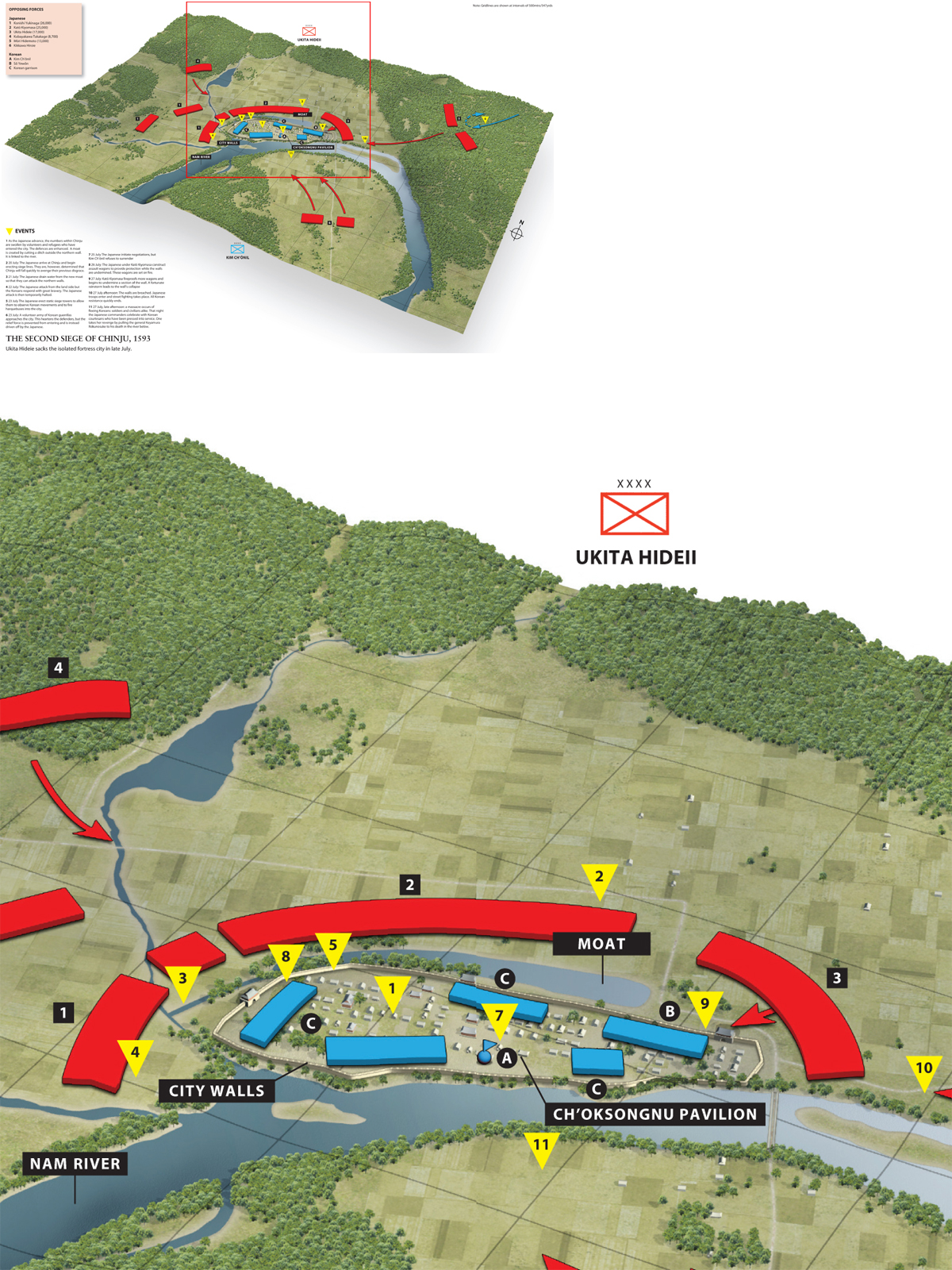

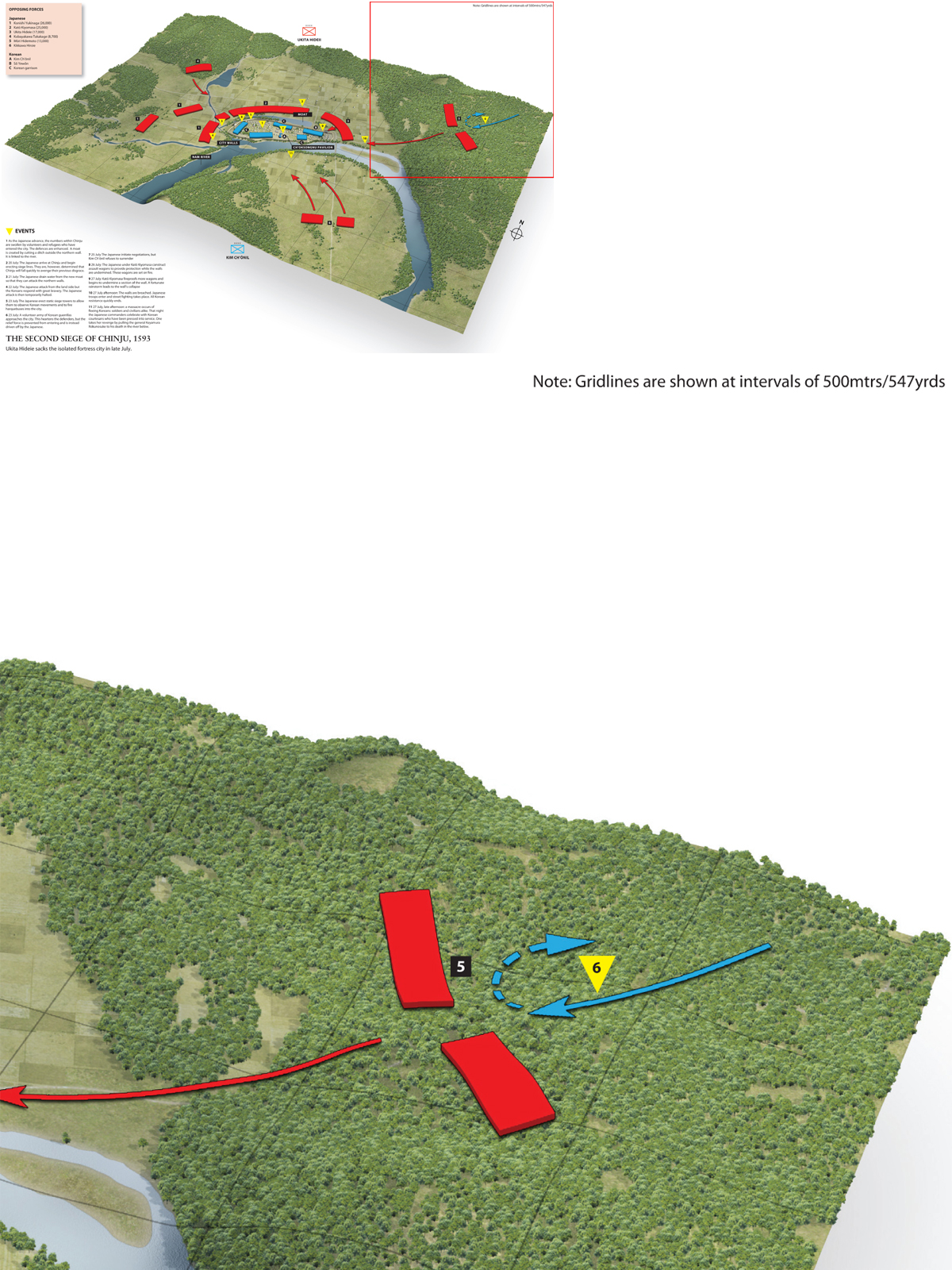

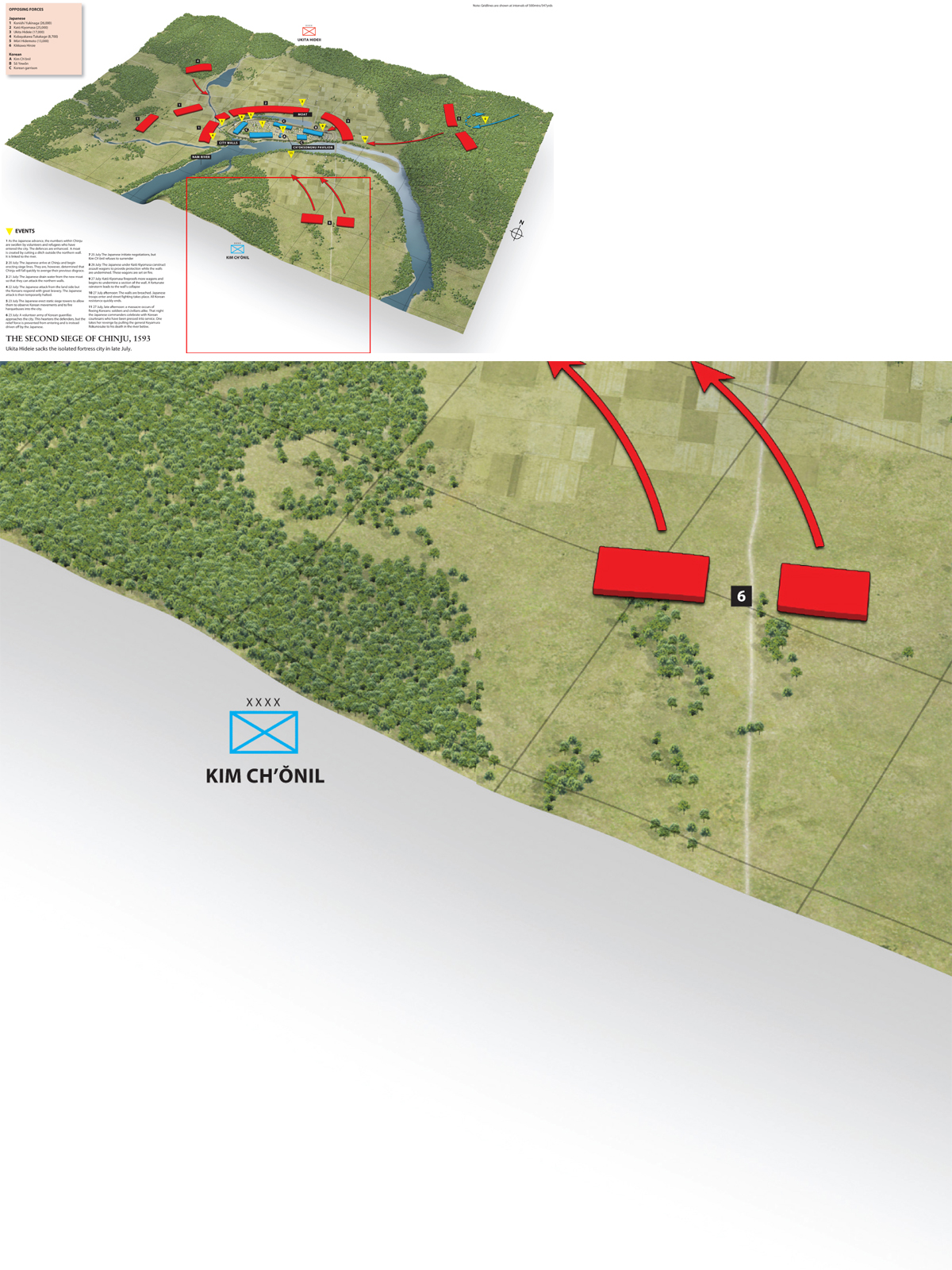

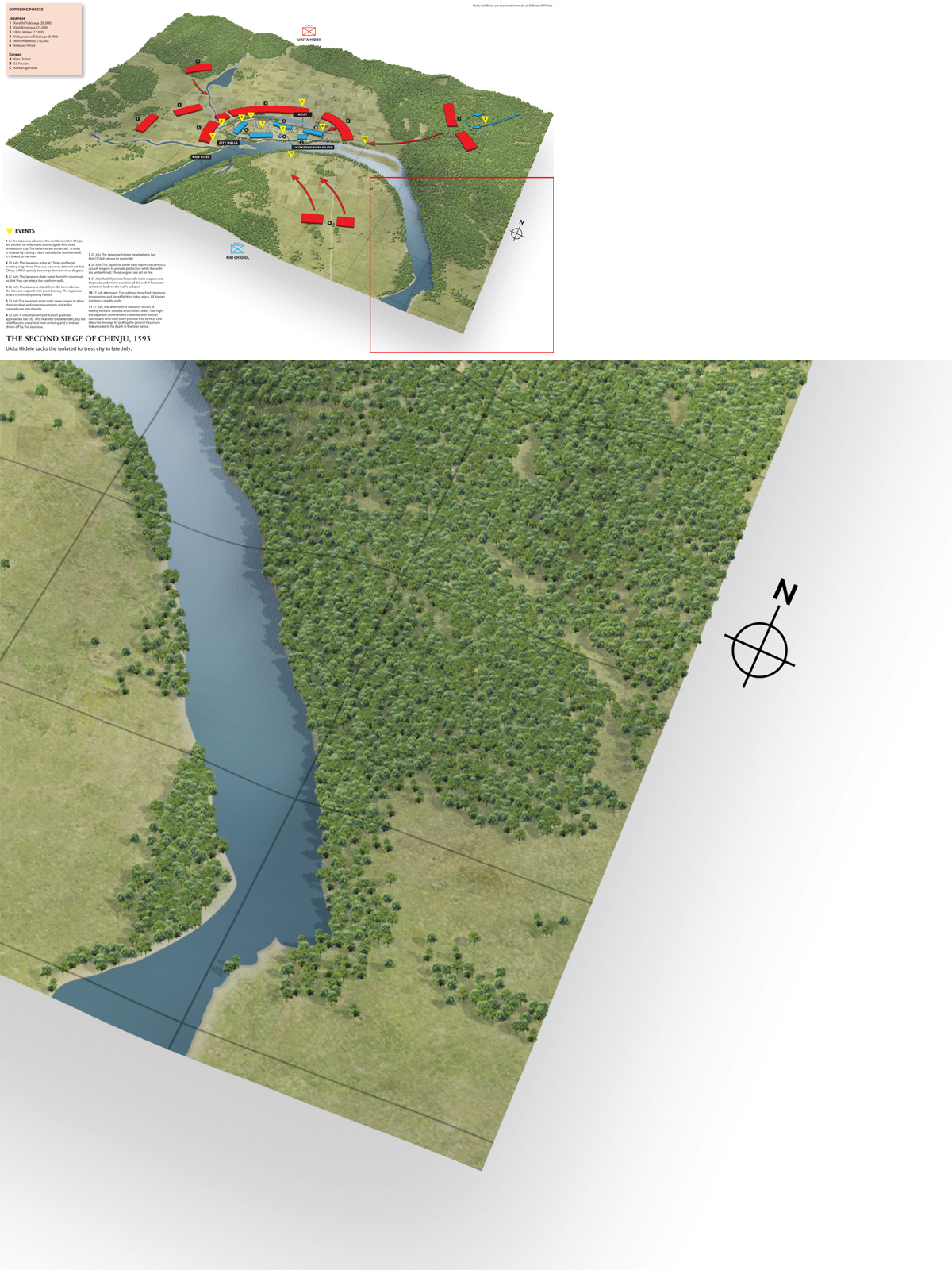

During the retreat to the coast the Japanese gained one last victory as an act of revenge, because the failure by the Japanese army to capture Chinju in November 1592 appears to have infuriated Hideyoshi more than any other defeat suffered at Korean hands. The debacle at Haengju could be seen to have been offset by the great victory at Pyŏkjeyek, while Hansando had happened as victories on land were being gained elsewhere. Chinju stood alone as a Japanese humiliation. It was a fortress apparently no different from any that had fallen so easily to Japanese attack during those triumphant first months of the march on Seoul, and, in view of the great strength of the Japanese forces that had been brought against it, the failure to take it was a disgrace that had to be expunged. Ukita Hideie committed a total of over 90,000 troops to the Chinju campaign, the largest Japanese force mobilized for a single operation in the entire war. At least half of these were reinforcements brought over from Japan and placed under generals who had already fought from one end of Korea to the other.

The Korean commanders learned of the new Japanese advance, but not knowing what might be the Japanese objective, Kwŏn Yul headed for Chŏnju while Kim Ch’ŏnil entered Chinju, and took charge of its defences against a possible attack. Chinju had a permanent garrison of 4,000, which soon grew to a possible 60,000 through the arrival of guerrillas, volunteers and many civilians, including women and children, who packed themselves into its walls. Chinju was protected to the south by cliffs overlooking the Nam River, and the long perimeter walls with towers and gateways that stretched round the city on the other three sides made it look like a miniature version of P’yŏngyang. Like P’yŏngyang, Chinju had a bower for viewing the river, the Ch’oksŏngnu Pavilion, which looked over the Nam River on the castle’s southern side. Some Chinese troops, who optimistically claimed to be the vanguard of a great force that was approaching from the north, entered the castle amidst great rejoicing.

The women at Haengju bringing stones in their aprons to the defenders of the mountain fortress, from the bas-relief on the monument on the site of the battle.

A view of Chinju Castle today, looking along the line of the Nam River.

On 20 July, the Japanese vanguard was observed to be constructing bamboo bundles and setting up wooden shields in sight of the walls of Chinju. To the west was Konishi Yukinaga with 26,000 men. To the north was Katō Kiyomasa with 25,000 troops, while to the east was Ukita Hideie in command of a further 17,000. Beyond them was a further ring of Japanese soldiers whose eyes were turned as much in the direction of a possible Chinese advance as to the castle itself. On the hills to the north-west stood Kobayakawa Takakage with 8,700 men, while Mōri Hidemoto and 13,000 troops covered the north and east. Finally, across the Nam to the south was Kikkawa Hiroie, with an unrecorded number of troops, ready to cut off any Korean guerrillas coming from that direction.

This unusual Japanese woodblock print depicts the second siege of Chinju. We see the use of cloud ladders, the hinged siege ladders on mobile carriages, and spiked boards that could be dropped from the battlements.

One of the Chinese defensive siege weapons used during the second siege of Chinju was this board studded with iron spikes. When dropped from a windlass it would clear the wall of scaling ladders. This full-sized reproduction hangs from the city wall of Pingyao in Shanxi Province.

The Chinju garrison had tried to augment their defences by cutting a moat from the stream that fed the Nam River to the north to flood part of the outer ditch to make a wet moat, but on the first day of the Japanese attack on 21 July advance troops broke the edges of the dyke and drained off the water. As they proceeded to fill the ditch with rocks, earth and brushwood, assault parties drew steadily nearer to the walls under cover of shields made from bamboo bundles, some of which may have been mounted on a wheeled framework. The Koreans replied with harquebuses, cannon balls and fire arrows, shattering or burning the bamboo defences. Two days later the Japanese tried the same technique that had been used during the first siege of Chinju by erecting static siege towers, to which the Koreans responded by increasing the defences within the castle and firing back. ‘His Lordship [Kim Ch’ŏnil] … secretly fired the cannons’, says a Korean account. ‘The cannon balls hit the lines, and the enemy generals fell to the ground.’ At about this time a local Righteous Army arrived in support, but was driven off by the Japanese rearguard.

The decisive moment in the siege of Chinju was the collapse of a section of the outer wall, brought about by undermining the foundations under the protection of turtle shell wagons, fortified mobile shelters. A fortuitous rainstorm completed the work. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

On 25 July, Ukita Hideie sent a message into the castle calling upon Kim Ch’ŏnil to surrender and arguing that if one general submitted then 10,000 peasants’ lives would be saved, but the request drew no response. Instead the inspiring figure of Kim Ch’ŏnil urged his men to fight to the last:

His Lordship had an inherent weakness in his legs and could not walk, so in the castle he travelled in a shoulder palanquin, but took little rest by day or night. He prepared rice gruel with his own hands, and made sure that the members of the garrison ate it. All the soldiers were inspired, and pledged themselves to the death.

It was now time for a major Japanese assault to be led by ‘tortoise shell wagons’, which were stout wooden ‘sows’ on wheels that were pushed up to the edge of the walls. Under the protection of the wagons’ boarded roofs, foundation stones would be dug out of the ramparts, leading to the collapse of a section. One account tells us:

At Kuroda Nagamasa’s duty station they filled up almost the whole width by working day and night. This was done by throwing grass into the ditch to make a flat surface. They tried to attack, but from inside the castle pine torches were thrown that set the grass alight. The soldiers inside the tortoise wagons were also burned and retreated.

The burning of the wagons, which was done by the simple expedient of dropping bundles of combustible material soaked in oil or fat from the battlements, drove off this assault. Undaunted, Katō Kiyomasa ordered other wagons to be prepared and had their roofs covered with ox hides for fire prevention. On 27 July a new attack began that concentrated on the wall’s cornerstones in the north-east, and a fortuitous rainstorm helped dislodge the foundations. The customary rush to claim the distinction of being first into the fortress commenced as soon as the stones in the wall began to slide, with samurai pushing each other out of the way. Seeing that Gotō Mototsugu, one of Kuroda’s retainers, was likely to be the first to climb in, Katō’s standard-bearer Iida Kakubei threw the great Nichiren flag over the wall to claim his place.

Keyamura Rokunosuke, also known as Kida Muneharu, died the most ignominious death in the whole of the Korean campaign. After the fall of Chinju he was embraced by a courtesan called Nongae, who then flung herself backwards over the parapet of Chinju castle so that both fell to their deaths on the rocks below. In this print by Kuniyoshi we see him in a more flattering pose fighting against the Jurchens in Manchuria in 1592.

By this time the garrison were so short of weapons and ammunition that they were fighting with wooden sticks, but at least one senior defender still had a sword. This was General Sŏ Yewŏn. When the Japanese broke in he opened one of the gates and sallied out twice to fight an individual combat with Okamoto Gonojŏ, a retainer of Kikkawa Hiroie. On the second occasion, however, Okamoto pursued him back to the gate and forced his way into the courtyard, where the injured and exhausted Sŏ was sitting on the stump of a large tree. Pausing for breath, Okamoto unsheathed his sword, leapt upon him and struck off his head. To one side of this place was the edge of a steep cliff, and Sŏ’s head tumbled down into the grass beneath. As it was unthinkable for a noble samurai to lose such a prized head a search was made of the riverbank until it was found.

Kim Ch’ŏnil was watching from the top of one of Chinju’s towers, and descended to the courtyard when he saw that the battle was lost. Accounts differ about how he died. One chronicler tells us that he ‘bowed to the north, threw his weapons into the river, and killed himself beside the well at the foot of the tower.’ Another states that he simply jumped into the river, as did many of the garrison, as noted by the chronicler of Katō Kiyomasa’s exploits, which states that ‘All the Chinese were terrified of our Japanese blades, and jumped into the river, but we pulled them out and cut off their heads.’ Kikkawa’s men on the far bank of the Nam River took a particularly active part in pulling escapees out of the river and beheading them. Some Japanese accounts note the taking of 20,000 heads at Chinju. Korean records claim 60,000 deaths, and both figures imply a massacre of soldiers and non-combatants alike.

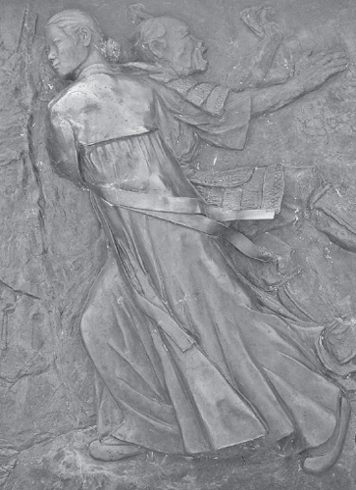

That night, while the Nam River downstream from the castle walls flowed red and headless corpses still choked its banks, the victorious Japanese generals celebrated in the Ch’oksŏngnu Pavilion, from which the best view of this hellish scene could be appreciated. The kisaeng (courtesan) girls of Chinju were pressed into the service of the conquerors, and entertained them in the pavilion above the now ghastly river. That night one kisaeng struck a blow for Korea. A courtesan called Nongae became a target for the amorous affections of Keyamura Rokunosuke, a senior officer in the service of Katō Kiyomasa. Luring him close to the cliff edge, Nongae locked her arms into his passionate embrace of her, and flung herself suddenly backwards into the river, clinging on to her victim until both she and he were drowned. Nongae now has a memorial shrine next to the pavilion on Chinju’s cliff, a heroine of the massacre of Chinju, Korea’s worst military disaster of the entire Japanese campaign.

Nongae was the courtesan who pulled Keyamura Rokonusuke to his death after the siege of Chinju. In this bas-relief at Chinju she performs her heroic deed of self-sacrifice.

Yet, just like Pyŏkjeyek, the victory at Chinju changed nothing. Instead of following up their triumph with a counterattack against the advancing armies the Japanese retreated still farther. They were soon within the safety of Pusan which, together with the chain of coastal fortresses known as wajō, was to become the only occupied territory in Korea for the next four years. These tiny outposts of Japan remained as coastal enclaves until the second invasion began in 1597.