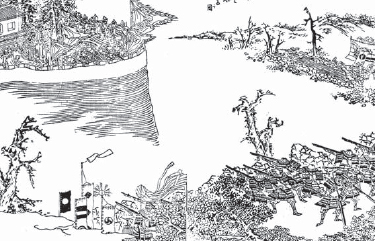

There was little military activity during the time of occupation. The invaders hung on to their coastal fortresses, but had almost no control over the rest of Korea, so the aim of the second invasion in 1597 was to put the matter right. Using the wajō as bases, a new army would land and advance on Seoul in an assault as rapid and as devastating as the blitzkrieg of 1592.

Unlike the 1592 offensive, the 1597 advance was conducted through the virgin territory of Chŏlla Province, from which Admiral Yi and the guerrillas had excluded the Japanese. It promised an alternative route to Seoul and fresh pickings for loot. The primary objective inside Chŏlla Province was its provincial capital Chŏnju, upon which two armies would converge. In overall command of the invasion was Kobayakawa Hideaki, heir of the late Kobayakawa Takakage. Ukita Hideie led the Army of the Left, while the former First Division of Konishi, Sō, Matsuura, Arima, Omura and Gotō were also present. Several other stalwarts of the first invasion such as Mōri Yoshinari and the Shimazu family made the total up to 49,600 men.

In the Army of the Right, of which 30,000 men supplied by Mōri Hidemoto made up nearly half the strength, the old Second and Third divisions loomed large in the persons of Katō Kiyomasa, Nabeshima Naoshige (now accompanied by his son Katsushige) and Kuroda Nagamasa, all of whom brought extensive combat experience to a total of 64,300 troops. By this time the wajō garrison strength already in Korea was about 20,000, making the full Japanese army approximately 141,100 men, a number that is very similar to the 158,700 of 1592. The Army of the Right was to march directly north-west while the Army of the Left would be ferried round the now peaceful south coast to Sach’ŏn, where it would march towards the untouched fortress town of Namwŏn.

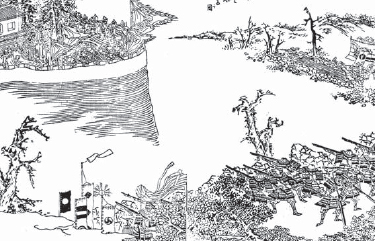

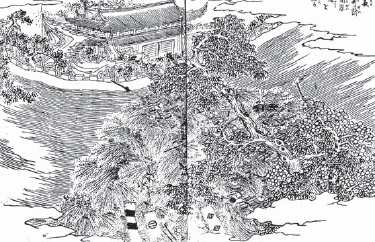

The Japanese army lays down a barrage of harquebus fire against the walls of Namwŏn. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi. The artist has tried to show the smooth-finished walls of Namwŏn that made climbing up so difficult.

The entry into Namwŏn of Yi Pongnam, as shown on a rather crude modern painting in the Memorial Museum, Namwŏn.

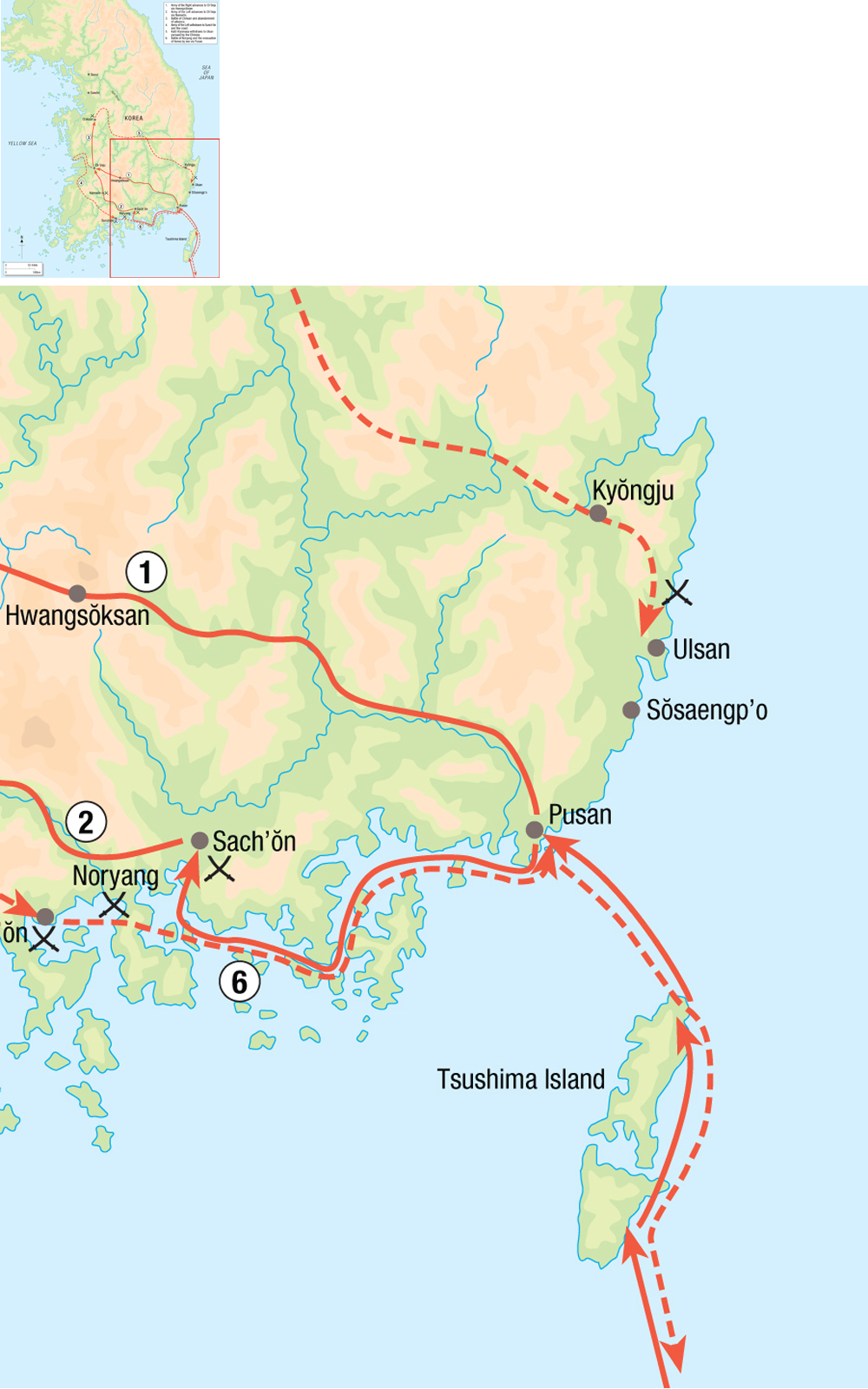

Namwŏn was a fortified town on a flat plain within encircling mountains, and therefore possessing none of the defensive features of the typical Korean sansŏng. To the south flowed a river, but this acted only as a distant moat. The town’s layout was that of a rectangle of stone walls, pierced at the centre of each side by a gateway. Between each gate and corner the wall was built outwards in the form of a simple square-sided rectangular bastion to provide flanking fire on to the gates. The wall was about four metres high, almost vertical on the outside with a more pronounced slope inside. It was apparently plastered with shell-lime, and tiny fragments of shells made its surface glitter.

A few miles to the north, however, lay an alternative defensive position in the shape of the sansŏng of Kyŏryŏng. Erected about halfway up a high mountain, the fortress wall extended round the contours of the hillside in the typical serpentine model. The decision about where to make a stand was settled with the arrival in Namwŏn of the Ming general Yang Yuan at the head of 3,000 troops. The Korean garrison were for moving to Kyŏryŏng, where the Japanese would have had to attack uphill through wooded terrain, but Yang Yuan overruled them. He then began an extensive programme to strengthen Namwŏn’s walls, adding another three metres to their height, and excavating a wide ditch six metres deep enclosed by a wooden palisade. Cannon were placed on top of the main gates and tree trunks were laid at the base of the ditch to slow down the attackers. A fortified reservoir to collect water was created outside the walls. Fences were also built out in the fields, but this tactic was to backfire when the Japanese used them as their own siege lines. The new defences had just been completed when the Japanese drew near on 22 September 1597 and, fearing lest the invaders should occupy Kyŏryŏng, Yang Yuan ordered its destruction.

A contemporary Japanese map of the layout of Namwŏn, probably created to press a claim for reward. (Namwŏn Memorial Museum)

The following day, as Japanese scouts began to appear, the defenders of Namwŏn were joined by Yi Pongnam, the military commander of Chŏlla Province, who arrived after much persuasion by Yang Yuan. There were now within the walls 6,000 defenders in total, split equally between Koreans and Chinese, together with almost as many civilians. On the attacking side Ukita Hideie took the southern sector, together with Wakizaka Yasuharu, Tōdō Takatora and Ota Kazuyoshi, while Konishi’s old First Division covered the western side. Kurushima Michifusa and Katō Yoshiaki provided the contingent to the north, where they joined the Shimazu force, while 11 other generals prepared lines to the east. While the Japanese were still preparing their positions the defenders sallied out against them, but they were met by detachments of harquebusiers, and speedily withdrew. The following evening, as on so many occasions at the beginning of the first invasion, a delegation was sent to the defenders calling upon them to surrender and allow the Japanese a free passage through, and as on all those occasions this was again rejected.

A Japanese monk called Keinen, who accompanied Ota Kazuyoshi as his chaplain and wrote a diary, notes that it rained ‘like a waterfall’, turning the whole Japanese camp into a swamp. The following day he had his first sight of combat, which filled him with sadness. ‘From along the whole line firearms and bows are being fired. One cannot but feel sympathy for those men who suffer death.’ This happened on 23 September, when small detachments of Japanese harquebusiers targeted the defenders on the walls from the cover of the ruins of the houses they had destroyed or from the outer fences erected by Yang Yuan. The use of small group tactics meant that the Chinese cannon did little harm to the besiegers. The main body, in any case, stayed back well out of range.

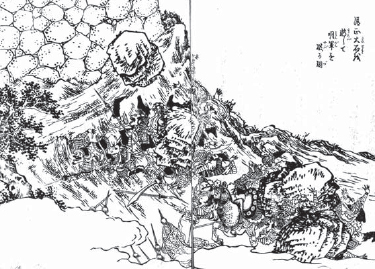

Namwŏn’s defences were only breached when the Japanese piled up a huge number of bales of grass and rice to fill the moat and make an unsteady ramp. From here the samurai climbed into the city. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

A very different view of the attack on Namwŏn comes from another follower of Ota Kazuyoshi, whose descriptions have a very different emphasis from those of Keinen. Okōchi Hidemoto’s Chōsen ki (Korean Chronicle) was designed to glorify the exploits of his master, and also, quite plainly, Okōchi himself, because his personal role in the fighting is related with great prominence. Several other accounts exist, and all agree on one thing. The earlier rain cleared and was replaced by a fresh, bright moonlit night that was ideal for an assault. The attacks began at 10pm, when ‘everything could be seen in minute detail’ because of the bright moonlight, according to the Shimazu chronicler. The Wakizaka ki (Chronicle of the Wakizaka family) describes Wakizaka Yasuharu fighting on the southern wall alongside Tōdō TaKatora:

From within the castle great stones were thrown and fell like rain, and there were many wounded and dead. To add to this the stone walls were high and coated over with plaster, so they could not easily make their entry. His Lordship and Takatora had scaling ladders set up, and although one or two men fought over them, they succeeded in making their entry.

Meanwhile on the western wall Matsuura Shigenobu had secured an area of the ramparts and sent his standard-bearers in to raise the Matsuura flags on high from the walls. This would encourage the other attackers, and also inform them that the Matsuura troops had got there first.

The initial attack was driven off, and the Japanese were actually held at bay for another four days before a clever stratagem broke the stalemate. In preparation for the assault the Japanese foot soldiers scoured the nearby fields, cutting wild grass and the rice crop, which would otherwise soon have been harvested, and tying the stalks into large bundles, which were thrown into the moat at a chosen position. So many were collected that a huge and unsteady mound extended to the level of the ramparts. While harquebuses raked the walls with fire, a tactic aided by another bright moonlit night, bamboo scaling ladders were added to the pile ready for a determined assault. ‘Around the evening of the day’, writes Yu Sŏngnyong in Chingbirok, ‘one could notice the soldiers guarding the ramparts of the fortress, whispering to each other and preparing the saddles for their horse. It was apparent they were anxious to escape.’

In this dramatic painting of the fall of Namwŏn on display in the Memorial Museum we see an entry being made by Japanese troops through one of the gates. No sooner are they inside than the disciplined ranks of harquebus troops are marshalled.

As the ramp neared completion fire arrows were loosed at the nearest tower, and when this was set alight the samurai rushed on to the huge heap of rice bales. Okōchi Hidemoto became the first to actually touch the wall. He heaved his body on to the parapet while behind him swarmed the Japanese footsoldiers, whom Okōchi refers to as ‘our inferiors’. Okōchi shouted for the flags to be brought up as quickly as possible, and dropped down into Namwŏn, proclaiming his name like the samurai of old. Japanese commanders’ flags now flew triumphantly from various parts of the wall, and numerous single combats began as the civilians huddled in their homes. Okōchi killed two other men, and:

Graciously calling to mind that this day was the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month, the day dedicated to his tutelary kami [Hachiman] Dai Bosatsu, he put down his bloodstained blade and, pressing together his crimson-stained palms, bowed in veneration towards far off Japan. He cut off the noses and placed them inside a paper handkerchief, which he put into his armour.

Very soon the Japanese assault party were faced with a counterattack from mounted men, yet even in all this confusion and danger the personal credit for taking a head was all important:

Okōchi cut at the right groin of the enemy on horseback and he tumbled down. As his groin was excruciatingly painful from this one assault he fell off on the left hand side. There were some samurai standing nearby and three of them struck at the mounted enemy to take his head. Four men had now cut him down, but as his plan of attack had been that the abdominal cut would make him fall off on the left, Okōchi came running round so that he would not be deprived of the head.

Nearby a bizarre encounter took place between a group of Japanese and a giant Korean swordsman two metres in height. He was dressed in a black suit of armour, and as he swung his long sword a samurai thrust his spear towards the man’s armpit, only to catch his sleeve instead. At the same time another Japanese caught the man’s other sleeve with his spear, ensuring that the warrior was now pinioned like a huge rod-operated puppet. He continued to swing his sword arm ineffectively from the elbow ‘as if with the small arms of a woman’, but the reduction of this once formidable foe drew only scorn from Okōchi. Impaled on two spears, and waving his arms pathetically, he reminded Okōchi of the statues of Deva kings in Buddhist temples with their muscular bodies and glaring eyes. With contempt and ridicule from his attackers the helpless giant was cut to pieces.

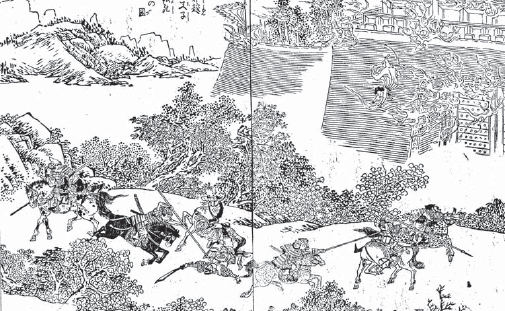

The pursuit after the fall of Namwŏn was a particularly terrible affair, with civilians being slaughtered along with fleeing soldiers. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

Soon Okōchi himself became a casualty. Attacked by a group of Koreans he was knocked to the ground, and as he was getting up several sword cuts were made to his chest, leaving him crouching and gasping for breath. His comrade Koike Shinhachirō came to his aid while Okōchi parried five sword strokes with the edge of his blade. A sixth slash struck home, cutting clean in two the middle finger of Okōchi’s bow hand, but Okōchi still managed to rise to his feet and quickly decapitated his assailant.

Advancing more deeply into Namwŏn’s alleys, Okōchi soon encountered another strong man dressed magnificently in a fine suit of armour on dark blue brocade. Okōchi was cut in four places on his sleeve armour, and received two arrow shafts that were fired deeply into his bow arm in two places, but in spite of these wounds he managed to overcome the man and take his head. Assuming that it belonged to a high-ranking warrior he took the trophy back to Ota Kazuyoshi. No one on the Japanese side was able to identify it, but after a short while it was shown to some Koreans who had been captured alive. They were taken aback, and as they looked at it in anger tears began to flow when they identified it as none other than the distinguished Kwangju magistrate Yi Chunwŏn. In the register of heads for the day this auspicious prize appears proudly next to the name of Okōchi Hidemoto.

Of the 3,726 heads counted that day, only Yi Chunwŏn’s was kept intact. The others were discarded after the noses had been removed, the beginning of the process of nose collection in lieu of heads that was to become such a feature of the second invasion. Insisting upon proof of his soldiers’ loyalty and achievements like the reward-giving generals of the ancient civil wars, Hideyoshi began to receive a steady stream of shipments of these ghastly trophies, pickled in salt and packed into wooden barrels, each one meticulously enumerated and recorded before leaving Korea. In Japan they were suitably interred in a mound near Hideyoshi’s Great Buddha, and there they remain to this day inside Kyoto’s least mentioned and most often avoided tourist attraction, the grassy burial mound that bears the erroneous name of the Mimizuka, the ‘Mound of Ears’.

Eventually the city gates were opened by the defenders themselves as they sought to escape, but when they saw the massed ranks of the Japanese many simply bowed their heads to be decapitated, but a certain Kim Hyouei jumped into a rice paddy and pretended to be dead. He lay there until the Japanese withdrew and finally escaped. More killings followed when the troops of Katō Yoshiaki and Shimazu Yoshihiro, who were guarding the northern road, turned about to cut down any survivors fleeing in that direction. After a few hours of night fighting, when the moon and the white walls of Namwŏn both turned red from flames and blood, ‘the torment was broken’ to use the words of the monk Keinen. The civilian survivors were wailing bitterly as he walked in shock round the streets of the town, but worse scenes were to greet him over the next two days when he left the town ‘and saw dead bodies lying near the road like grains of sand. My emotions were such that I could not even glance at them’. As he walked farther on he found more nose-less corpses in nearby houses, ‘and this went on into the fields and mountains’. In the Wakizaka ki, however, the slaughter of civilians was just another phase in the military operation:

From early dawn of the following morning we gave chase and hunted them in the mountains and scoured the villages for the distance of one day’s travel. When they were cornered we made a wholesale slaughter of them. During a period of ten days we seized 10,000 of the enemy, but we did not cut off their heads. We cut off their noses, which told us how many heads there were. By this time Yasuharu’s total of heads was over 2,000.

The bad news from Namwŏn travelled quickly northwards to the other Korean garrisons, and after just two days the Japanese Army of the Left marched out of Namwŏn to the provincial capital of Chŏnju and found it abandoned. The great prize of Chŏlla Province, the one piece of south Korean territory that had eluded them for the whole of the first invasion, was now securely in Japanese hands.

The cataclysmic battle at Namwŏn, which is so well known and well recorded by both sides in the conflict, has completely overshadowed another successful battle fought by the Army of the Right the following day. This army was the larger of the two Japanese contingents. It faced resistance only from the sansŏng of Hwangsŏksan, an isolated mountain fortress that lay just east of the Chŏlla provincial border on top of a wooded hill. Its defenders had hastily recruited an army from the neighbouring districts, and many thousands of Korean troops were packed inside it. Katō Kiyomasa drew up his men to the south. Nabeshima Naoshige took the western station, while Kuroda Nagamasa covered the east. During the night of 27 September the Japanese took advantage of the moonlight that had aided the capture of Namwŏn the day before, and began a full-scale assault. The victory was as quick and as complete as that of Namwŏn, and 350 heads were taken.

There was no further opposition as the Army of the Right marched on to join their comrades in Chŏnju, but the threat to Seoul was becoming obvious to the Koreans, so a largely Ming force was hurriedly dispatched to halt their progress. The Chinese general advanced cautiously towards the town of Chiksan, where scouts informed him that the two armies were now but a short distance apart. Here he waited, and before long the Japanese force, which was under the overall command of Kuroda Nagamasa, also sent forward a vanguard unit. As dawn broke Nagamasa’s vanguard reached a vantage point five kilometres north of Chiksan, from where they had a good view of what appeared to be an immense Chinese horde below them. It was also obvious that the Chinese had seen them too, which placed the Japanese leadership in something of a quandary, because if they retreated the Chinese would pursue them and occupy the favourable ground that would allow them to fall upon Kuroda’s troops. If the Japanese vanguard attacked they were likely to be annihilated, but in so doing they would slow the enemy advance and perhaps hold them down on the plain while Kuroda’s main body followed. The crucial strategic objective appeared to be a rough earthen bridge across the river, to which the Chinese were heading. So, comparing themselves favourably to the ‘forlorn hope’ troops who had goaded Takeda Katsuyori into attacking at the famous battle of Nagashino in 1575, the Japanese advanced. On coming within range of the Chinese the foot soldiers opened up with their harquebuses, and the samurai attacked through the clouds of smoke.

While a fierce hand-to-hand battle ensues outside, the defenders and their families in the burning fortress of Hwangsŏksan commit suicide. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

The sound of firing reached Kuroda Nagamasa long before any of his messengers. A mounted unit under Gotō Mototsugu was sent directly forwards, while Kuroda rode out in support with the rest of his army as other messengers hastily galloped back to Mōri Hidemoto. When Gotō arrived on the higher ground he immediately comprehended the situation. The Japanese vanguard had advanced across the earthen bridge to engage the Chinese. They were now fighting with their backs to the river and were being slowly pushed back. The chronicler of the Kuroda family puts the following heroic words into Gotō’s mouth, ‘… if the bridge is crossed by that great army then surely they will attack Nagamasa’s main body …, so, accepting that only one man may be left alive for every ten that are killed, we must defend the bridge and prevent the enemy from crossing.’

Gotō therefore set off in a charge down the hill and led an advance across the river. The shock of the attack drove the immediate enemy back, and rallied the distressed Japanese. As soon as he was assured that the position had been reversed, Gotō withdrew his mounted force and returned to the high ground, where, according to the chronicler ‘he came and went at various places, and gave the impression that the Japanese were a large force.’ Very soon this impression became a reality when Kuroda Nagamasa appeared with the rest of his army. They quickly engaged the Chinese, whom they began to drive back until the Chinese were reinforced in their turn by 2,000 troops from Suwŏn. Once again the fierce fighting continued with no advantage to one side or the other, but then the final set of reinforcements arrived. These were Japanese, and consisted of Mōri Hidemoto’s army. The arrival of their overwhelming numbers made the Ming army withdraw towards Suwŏn, but as it was now growing dark the Japanese command felt it imprudent to pursue them, so both armies disengaged.

A massive Ming army gathers to destroy the wajō of Ulsan, from a painted screen commissioned for the Nabeshima family, now owned by Saga Prefectural Museum.

This battle of Chiksan left the Japanese poised for a quick advance on Seoul and the achievement of Hideyoshi’s war aims. But if Chiksan may have been an indecisive battle, it had decisive results. The post-Namwŏn panic that had seen Korean and Chinese armies abandoning positions had now been arrested, and it was clear that a large Chinese army was preparing to defend Seoul. Chiksan was therefore occupied by the Japanese to use as a base for the attack on the capital.

An advance on Seoul, and a re-run of their triumph in 1592, was therefore expected, but, just as at P’yŏngyang in 1592, the necessary troops never arrived and Chiksan was to become another last outpost of a Japanese advance. Seoul was never taken, and the reason why the attack never happened was again the result of a naval victory gained by Admiral Yi Sunsin at Myŏngyang. The ‘miracle at Myŏngyang’ as the Koreans called it prevented any movement of Japanese troops round the west coast of Korea through the Yellow Sea. With no reinforcements and a major Chinese advance another Japanese retreat was inevitable. It ended at the much-extended line of wajō that protected the coast. Three great sieges at Ulsan, Sunch’ŏn and Sach’ŏn followed, as described in my book Fortress 67: Japanese Castles in Korea 1592–98 (Osprey Publishing Ltd: Oxford, 2007). All were Japanese victories, but each was completely nullified by the overall situation, which was that of covering the final evacuation to Japan and an end of the Korean invasion.

The final trigger for the Japanese evacuation was the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. A withdrawal may have been inevitable anyway, but the commanders on the ground now had the freedom to act according to their own assessment of the situation. The Ming army on the eastern side of Korea, which was monitoring local movements after withdrawing to its base at Kyŏngju, became aware of troops moving out of Ulsan and Sŏsaengp’o and heading for Pusan. There was less movement over in the west because the allied navies were keeping Konishi Yukinaga confined to barracks in Sunch’ŏn, but the news of Hideyoshi’s death finally leaked out to the ears of the Korean and Chinese. It was now certain that Konishi would attempt to escape, but the allied blockade was tight, so for the last time in the campaign Konishi Yukinaga turned to negotiations to ensure a safe passage. The Chinese admiral Chen Lin proved quite amenable to his advances, but Admiral Yi Sunsin would not agree to lift the blockade.

The Chinese had clearly had enough of war, and as Chen Lin was willing to let the Japanese go without further bloodshed, he proposed to Yi that he, Chen Lin, should conduct an operation against Sō Yoshitomo’s small wajō on Namhae Island. Apart from the inherent promise of a final portion of military glory, Chen Lin also hoped that Konishi might take advantage of his absence and settle the matter by default by running the blockade. Yi, however, was greatly indignant at the suggestion of an attack on Namhae, which had long been within his sphere of influence. He knew that many Korean civilians were virtual prisoners of the Japanese there, and he feared that the Chinese would be unable to discriminate between them in a raid. Chen’s subsequent and outrageous comment that any such Koreans should be regarded as collaborators who deserved to die anyway, confirmed Yi’s worst suspicions about his ally and roused him to fury.

Nevertheless, the result of Konishi’s determined pressure on the Chinese admiral ensured that one boat at least was able to escape from Sunch’ŏn. ‘Yesterday two blockade captains … chased a medium-sized Japanese vessel fully loaded with provisions that was crossing the sea from Namhae’, wrote Admiral Yi in what was to prove the last diary entry of his life. The ship was apprehended on its return, but a chain of signal fires then sent plumes of smoke from one wajō to another to inform Konishi that the message had succeeded in getting through. The troops stationed in Sach’ŏn, Kosŏng and Namhae quickly gathered at the agreed rendezvous point in the bay of Sach’ŏn, where they would be joined by Konishi for the voyage home. But when two days had passed and Konishi had not appeared, Shimazu realized that Konishi was still being prevented from leaving. The decision was therefore made to send 500 ships to Sunch’ŏn to run the blockade. The shortest route between the two bays was to head due west, and pass between Namhae Island and the Korean mainland through the narrow strait of Noryang.

The Noryang straits, between the island of Namhae and the mainland, were the site of the final battle of the Korean campaign, where Admiral Yi Sunsin was killed at the moment of victory.

The defenders of Ulsan drop rocks down onto the Chinese besiegers. From Ehon Taikōki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

Scouts and local fishermen informed Admiral Yi of what was happening. Anticipating that the Japanese fleet would take the direct route through the Noryang straits Yi drew up his fleet in the open sea just to the west of the narrow stretch of water. Late at night Yi was told that the Japanese fleet had sailed into the Noryang strait and was anchored for the night. It was the perfect opportunity for a surprise attack, which was launched at 2.00am on 17 December 1598. The battle, most of which took place in the narrow sea area that now lies under the Namhae suspension bridge, was conducted in perfect Korean style, and within hours almost half the Japanese fleet was either broken or burned. Admiral Yi was in the thick of the fighting, and personally wielded a bow when he rowed to the aid of Chen Lin, whose flagship came under attack from a group of Japanese ships. By the time the dawn was breaking the Japanese ships were retreating, and, sensing that this could be the last time for them to come to grips, Yi ordered a vigorous pursuit. It was at that moment, when victory was certain, that a Japanese sharpshooter put a bullet into Yi’s left armpit. He was dead within minutes. Only three close associates saw the incident, and with his dying breath Yi asked them to keep his death a secret, so his body was covered with a shield and the battle of Noryang continued towards its victorious conclusion.

The death of Admiral Yi Sunsin, killed on board his flagship at the moment of his final victory like Nelson at Trafalgar, was a tragedy that deprived Korea of its ablest leader and greatest hero. Out of 500 Japanese ships only 50 survived to limp home. Shimazu Yoshihiro himself narrowly escaped death while other commanders provided protection from the Chinese ships that harassed them for a considerable distance.

There was only one act left to play in the drama of the Korean evacuation. Many Japanese soldiers and sailors had escaped to land on Namhae Island and took temporary refuge in Sō’s now deserted wajō. The allied fleet burned any Japanese ships remaining in Noryang, so the survivors faced a long trudge across the mountains to its eastern coast. Five hundred of them were eventually rescued, probably by Konishi’s fleet, which took advantage of the battle to slip out of Sunch’ŏn. They headed for Kŏje Island round the southern end of Namhae and docked at Pusan, Japan’s last continental possession. Three days later the final evacuation began, and by the dying days of 1598, all the invaders had disembarked in Japan, where many heard for the first time the news that Hideyoshi was dead.

Back in Korea the Chinese and Korean forces began to enter and occupy the now deserted wajō of Ulsan, Sŏsaengpo, Sachŏn and Sunchŏn. Admiral Chen Lin even discovered some Japanese stragglers on Namhae Island who had not managed to make it to the eastern coast to be rescued by Konishi. They were all beheaded with great glee, and their heads taken to the Korean court as proof of the valuable role played by Korea’s Chinese allies, but certain Korean officials suspected that in Chen’s desire for a final glorious flourish, the Koreans on Namhae whom he had labelled collaborators had also been cut down, the tragic outcome that the late Admiral Yi Sunsin had so feared. It was a suitably sad ending to a long and terrible war.

During the Korean campaign Katō Yoshiaki (1563-1631) was one of Hideyoshi’s admirals, a position in which he had shown considerable aptitude in Hideyoshi’s domestic wars. In this print by Kuniyoshi, however, he is shown standing on the battlements of one of the Japanese wajō forts.

A very good fibreglass replica of an ordinary Korean soldier at the Nagan Village Folk Museum near Sunch’ŏn. Unlike the Japanese foot soldiers Koreans wore no armour.

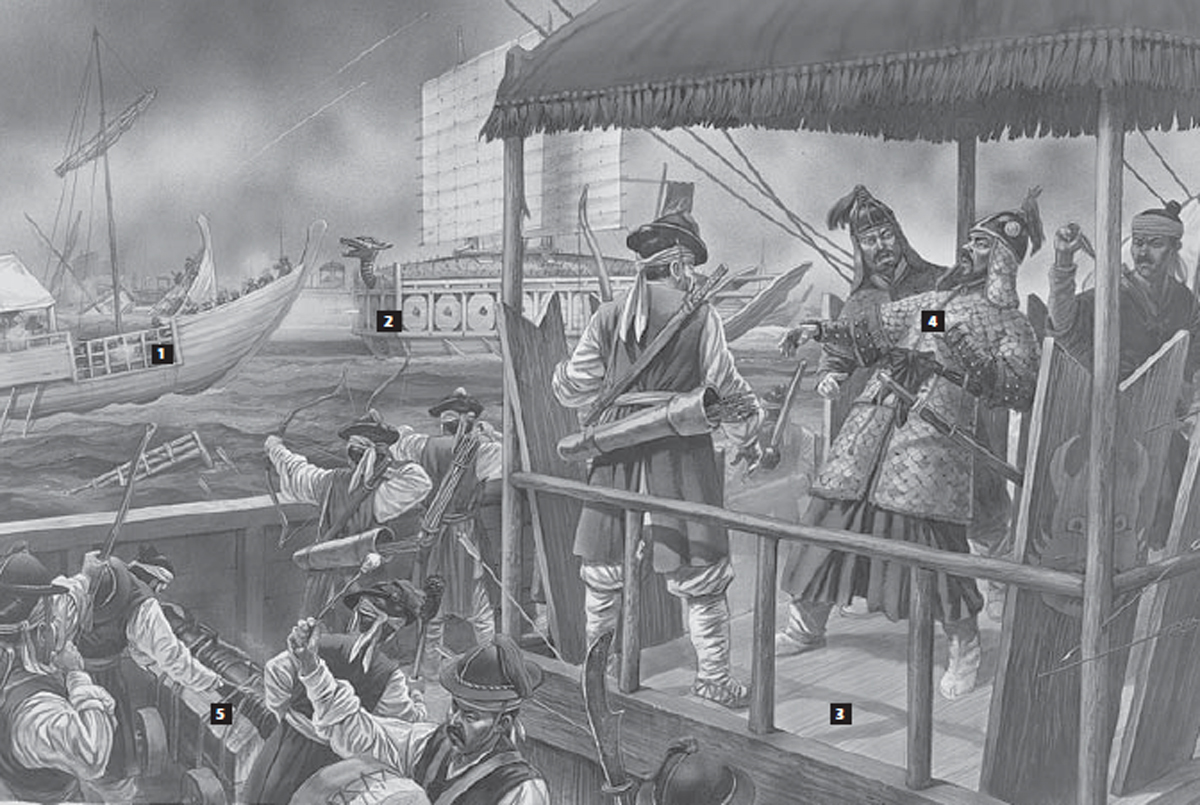

THE DEATH OF ADMIRAL YI AT THE NAVAL BATTLE OF NORYANG 1598 (pp. 88-89)

The battle of Noryang, fought in the straits that divide Namhae Island from the mainland, was the last battle of the Japanese invasion where the Korean navy gained a considerable victory over the Japanese fleet that was trying to escape. Tragically, at the height of the battle Admiral Yi Sunsin, Korea’s greatest hero and the architect of so many naval victories, was hit by a bullet, and died on in the command tower of his ship as news was brought to him of his victory. To the rear of the plate the sea battle is at its height. As the Japanese army is evacuating Korea every ship has been pressed into action, even the lightly armed kobaya warship from which harquebuses are being discharged against the Korean fleet (1). One of the famous Korean ‘secret weapon’ turtle ships is shown firing a cannon (2). This is based on a reconstruction in the National War Museum in Seoul, which is now accepted as the most likely appearance of the legendary ship, even though there is still some controversy over whether or not the gun crews shared the same deck as the oarsmen.

The metal spikes on the upper deck discourage boarding. Admiral Yi is not on board a turtle ship but commands from an open-decked p’anoksŏn (3). This has proved to be his undoing, because a Japanese bullet has hit him. Dropping his baton of command Yi falls. His shocked followers will conceal his body so that morale does not collapse. Yi is wearing a very fine general’s armour of gold-plated metal scales over a heavy armoured coat. Beneath the armour is a heavy blue brocade robe (4). All around him the fighting goes on. A drummer stirs the fighting spirit. Korean archers shelter behind tall wooden shields or the gunwales of the ship and keep up an arrow barrage against the Japanese. A bigger punch is packed by the iron cannon, which is lashed using rope to a wheeled gun carriage and is about to be discharged against the nearest Japanese ship (5). The plate is based on drawings of the appearance of various Korean ships and an oil painting in the Memorial Shrine to Admiral Yi on the island of Hansando.