The nationalist movement into which Magnus had been drawn by the solicitations of his friend Meiklejohn and by the impetuosity of his own nature, suffered from an unusual handicap. The normal preamble to a revolution or separatist movement is a phase of violent oppression by some foreign power or social minority, and the Scottish Nationalists were unfortunate in not being able to point to any gross or overt ill-use at the hands of England. Except for a few surviving Jacobites they had no passionate red embers to fan to a certainty of flame, and the stolid temper of lowland Scotland was not inclined to waive the material advantages of stability for the gambler’s increment of change. The Nationalists’ arguments were many, and many of them were sound, but they had small chance of influencing people who had forgotten or not yet learned or were by nature disinclined to think for themselves. Economic reasons and valid patriotic sentiment are both insufficient, without assistance from some sensational train of incidents, to overcome the inertia of a modern democracy, and so the Scottish Independents consisted mainly of spirits congenitally factious, of a small minority, mostly young, who had read history and considered the economic problem in some detail and with an open mind, of remaining Jacobites, of a few Liberals who remembered the early doctrines of their party, of some eccentric ladies, and of an insecure working-class element, more susceptible to sentiment than their bourgeois neighbours, and who further believed that any change from the existing order of society would of necessity be for the better. Vested interests were openly hostile to the movement, and the great majority of middle-class people were indifferent to it with the calm indifference of ignorance.

Magnus soon discovered that Meiklejohn’s estimate of the situation was quite erroneous, but to counter this he developed a firm conviction that the Nationalist cause was justified, and presently his conversation assumed the very tone and colour of Meiklejohn’s optimism, and he would assure casual acquaintances and passing friends that the country was ripe for independence, and they, did they not join the Party immediately, would be left with the laggards and the slaves far in the rear of a triumphant nation marching to the goal of its assured destiny.

He met Skene again, and argued with him hotly but amicably. He was introduced to other Nationalists, and in return for his, heard their perfervid views. His novel was still selling, and the modest fame he had won by it assured him, among friends, of a respectful hearing and persuaded his fellow-members of the Party that his accession to it was of unusual value. He wrote several times for the obscure periodicals that favoured the cause, and Meiklejohn, braving the proprietors’ wrath, asked him to contribute a series of articles on the general aspects of small nationalism to the evening paper which he edited. He addressed two or three small outdoor meetings, but his arguments were too remote and his language too learned to rouse excitement in a street audience. In a very short time, however, all the Nationalists in Scotland had heard of their new recruit, and many of them were gratified by the conversion of so distinguished a person.

In the flush of this political excitement Magnus discovered the subject for a poem. It was to be called The Returning Sun, and it was to picture a Scotland glorious in the revisiting of its ancient pride. But the first part was to satirize, very pun-gently, the existing Scotland of commercialism and dullard resignation to a dwindling name, and he was already taking great pleasure in the composition of this prelude.

Being so strenuously occupied he did not see Frieda again for rather more than a fortnight. He telephoned her once or twice, but owing to his other engagements they were unable to arrange a meeting. Then, late one afternoon, she rang him up and asked if she might come to see him that evening. It happened that Magnus was going to a soirée given by one of the few wealthy Nationalist supporters, a genial, enthusiastic, elderly Jacobite named Sutherland, whose acquaintance many members of the Party were glad to foster and whose hospitality they accepted with great willingness. The soirée was not meant as idle entertainment, for a political discussion had been arranged, but in spite of this Magnus invited Frieda to dine and afterwards go with him to Mr Sutherland’s. He hoped, incidentally, to impress her with the reality and importance of their aims, for that afternoon he had been talking to a Mr Newlands, whose duty it was to open the discussion, and Mr Newlands had promised him fireworks.

He was a solid-seeming man, black-haired and dark of complexion, whose manner of speech gave to every word the semblance of deep significance. He spoke in a quiet voice with ever and anon a sidelong glance of the eyes as though to make sure that no English spy was listening. Then he would thrust forward his head, tap his listener with a strong forefinger, and speak in yet more thrilling tones.

He had said to Magnus, ‘When Sutherland asked me to speak tonight, I refused. It’s a dilettantish crowd he gathers there, not ripe for the real stuff, and I was afraid there would be unpleasant scenes if I told them the truth. I don’t want women screaming in the middle of my speech. But he assured me that he would back up all I cared to say, and that all the people he had invited for tonight could stand anything. So then I agreed to speak. I don’t know what the others mean to say, but there’ll be no milk-and-water about my address. There’ll be no namby-pambyism from me’.—He looked round cautiously to see if the English Government had a spy in the vicinity.—‘I’m going to detail a plan for immediate action! I tell you, Merriman, there’ll be fireworks tonight!’

In high expectation Magnus warned Frieda to pay close attention to what Mr Newlands would have to say: ‘I know you haven’t a very great opinion of Nationalism, but you’ll change your mind when you’ve heard Newlands. There’s nothing dilettantish or impractical about him. His plans are complete, and he’s going to explain how to attain independence immediately.’

Mr Sutherland welcomed them with exuberant kindliness. He was wearing full Highland dress, and his plump figure was of such noble circumference that his kilt might almost have served as a tent. His face shone like an October moon. His guests, of whom there were about thirty, were already being pressed, not merely invited, to eat sandwiches and drink whisky, cocktails, claret-cup, or several liqueurs, and the atmosphere was already lively enough for the birth of revolution, though many of the guests appeared hardly suitable witnesses for so violent an accouchement. There were several ladies of advancing years who spoke very loudly to various mild-looking young men who listened in gloomy silence. Hugh Skene was there, and so were McVicar, Francis Meiklejohn, and Mrs Dolphin. A hearty and excitable young man in a kilt was talking about vice and other modern topics to a girl with a blank expression and a long cigarette-holder. A pleasant motherly woman was listening with commendable patience to a Breton separatist who knew but little English, and McVicar, still in Meiklejohn’s best evening trousers, was arguing under circumstances of equal difficulty with a polyglot Czech who had learned all his languages in prison, and was handicapped by a purely theoretical knowledge of their pronunciation.

Presently Mr Sutherland intimated that the formal discussion was about to commence, and ushered his guests into another room where seats had been arranged for an audience—an audience of potential speakers, that is.

Mr Newlands rose to open the debate. He stood beside a window concealed by high curtains, and before saying anything he looked rapidly behind them to make sure that no hostile agent was concealed there. Then he inclined his body forward, thrust at the air with a stiff forefinger, and spoke in low conspiratorial tones.

‘The time has come,’ he said through clenched teeth, ‘the time has come to take the next step! We have talked long enough about Scotland’s grievances, and now the fateful hour has arrived when we must redress them. Mere talk is not enough. Talk has served its purpose, and now we require action. What we must immediately decide is this: the proper mode of action, and the proper hour for the attack! But before explaining my plan of campaign—and my plan is complete—I should like to review, as rapidly as possible, the existing situation.’

Mr Newlands then proceeded to catalogue the Scottish grievances and to reveal, with the help of copious notes, the statistical plight of the shipbuilding industry, the textile industries, of farming and fishing, of the railways and the coal-mines. The figures he quoted were known, in varying degrees of accuracy, to everyone in the room, and though some listened with great pleasure as to a familiar and accepted creed, there were others who revealed a certain impatience. Among these was Magnus. While Mr Newlands had stood waiting for silence in which to begin his epochal speech, Magnus had whispered to Frieda: ‘Now listen to this! We may make history tonight.’ But as the monotonous recital of figures grew longer and longer, and the procession of accepted facts stretched its weary length through time, he became restless and finally dismayed. Beside him Frieda yawned widely.

Mr Sutherland fidgeted with his watch. Presently, in the politest and most genial way, he interrupted Mr Newlands and said he had already exceeded the time allotted for his speech, and he must call on Mr Skene to continue the discussion. There was some altercation at this decision, for as yet Mr Newlands had revealed nothing of his revolutionary plan, and many people wanted to know what it was. Magnus got up and suggested that in consideration of the importance of Mr Newlands’s promised announcement he be allowed to continue his speech for another five minutes.

‘I should require more time than that,’ said Mr Newlands. ‘I can’t say exactly how long I need, for the speech I have prepared is, as you say, an important one, and there’s nothing I could conscientiously leave out or even cut short.’

At this there woke a babel of talk, for nearly everybody had prepared a speech at least as important, in his or her estimation, as Mr Newlands’s, and while no one desired to prohibit that gentleman from speaking, everyone naturally wished for an opportunity to air his or her views. Gradually the confusion of tongues subsided, not so much in voluntary abandonment of argument as under compulsion, for now a clear female voice was dominating the storm, and before its authority the others fell mute.

The floor had been taken by a young woman who bore a striking resemblance to popular pictures of Joan of Arc, and she was talking with evangelical earnestness about Ireland. Her fluency was remarkable but her meaning was somewhat obscure, for though it was obvious that she had a great admiration for Ireland and thought that Scotland should follow its political example vi et armis, it also appeared that she was a fervent pacificist and desired to abolish all weapons from howitzers to rook-rifles. She concluded her speech with a rhetorical gesture and a tangle exordium in which Scotland was commanded to be true to herself.

Then Mr Sutherland introduced Hugh Skene, and the poet, with burning intensity, declared that he was a Communist. But he also referred, with dark elusive details, to some private economic policy of his own that was, apparently neither communistic nor capitalistic, but ideally suited to modern conditions. He refused to explain the system because, as he logically declared, an explanation would be wasted on people still ignorant of its fundamental hypotheses. Those hypotheses they must discover for themselves. His advocacy of nationalism, he said, was mainly due to his desire to see this system established, at first in Scotland and then throughout the world. Lest his hearers should consider him a materialist, however, he hotly denied any concern with the increase of wealth that might be expected to accrue from his policy. ‘I have no interest whatsoever in prosperity,’ he declared, and left the uncommon impression that here was a man who advanced an economic theory for purely aesthetic reasons.

He was followed by McVicar, who quoted a few equations from Karl Marx, a recondite excerpt from The Golden Bough, and a long sentence from Ulysses. He created a strong feeling that Scotland was in the throes, if not of renascence, at least of some experience equally shattering. After his address the action became general, and it was hardly possible to distinguish one speech from another. Most of them referred to deer-forests, Bannockburn, rationalization, and Robert Burns, and every third sentence began with the first-person singular pronoun. When the fray grew scattered Mr Sutherland rose and said they were all pleased to have with them, that evening, the Party’s distinguished new recruit, Mr Merriman, and now would Mr Merriman continue the discussion?

By this time Magnus was in a somewhat contentious ill-humour, and he spoke with unnecessary vehemence.

‘I am a Scottish Nationalist,’ he said, ‘because I am a Conservative. I believe in the conservation of what is best in a country, and what is truly and desirably typical of it, and I believe that small nations are generally more interesting, more efficiently managed, and more soundly established than big ones. I am not a Communist, a Socialist or a Pacifist and I strongly protest against the association with Scottish Nationalism of any tenets of Communism, Socialism or Pacifism. Communism is an Oriental perversion, Pacifism is a vegetarian perversion, and Socialism is a blind man’s perversion. There are two essential factors in any national movement: a leader or leaders of a suitable kind, and a sufficient number of people who can be persuaded or compelled to follow them. At present Scotland possesses neither of these factors, and our first task is to find them.’

This speech was received with great indignation, and half the audience rose to protest publicly while half looked round for suitable confidants to receive their private resentment. But Mr Sutherland quelled the disturbance by loudly announcing that the time was opportune for more refreshment, and began to shepherd his guests into the former room, where the supply of sandwiches had been renewed and still more bottles stood close-ranked on the vast sideboard.

Magnus found himself buttonholed by the young woman who looked like Joan of Arc. She introduced herself as Beaty Bracken. Magnus had heard a good deal about her, and he was interested to meet her, for she had recently achieved fame by removing a Union Jack from the Castle and placing it in a public urinal. She began to speak familiarly of war and peace, and said that another great war was surely imminent, for on all sides people were talking of it and it was well known that there was no such breeder of war as talk of war.

Magnus said, ‘Then surely it would be wise of you to stop talking about it.’

‘But women must talk about it, because women can do so much to prevent it,’ said Miss Bracken earnestly.

‘Is woman’s influence always pacific? I seem to remember historical examples of rather warlike women.’

‘Ah, but not women who were mothers!’

‘In the last war there were plenty who boasted of having “given their sons to Britain”. From Sparta onwards history is full of belligerent mothers.’

‘But they went into battle beside their sons.’

‘Who did?’ asked Magnus, ‘and when?’

‘There was Dechtire for one.’

‘Who was she?’

‘She was the mother of Cuchullin. She was also an ancestress of mine.’

By this time Magnus had quite forgotten the subject of the argument, and it was clear that Miss Bracken had never known. He told her, in reply to her claim on Cuchullin’s blood, that he himself was descended from St Magnus of Orkney, and then he was extricated from the fog of Irish mythology and Norse genealogy by a vivacious lady with heavy ear-rings, an eager vulpine look, and a voice like a macaw’s.

‘Mr Merriman!’ she cried, ‘I’ve been dying to meet you! I’ve read your book. Such a terribly naughty book! Such a terribly naughty man you must be! It frightens me to death to talk to you really, but I feel I must. I told my husband I was going to meet you tonight, and he told me I’d better take care. Ha-ha-ha! What a lot you must know to write a book like that! However did you learn it all? No, don’t tell me, don’t tell me. I couldn’t bear to hear it. Too naughty! But I love to read about it. And now you’re a Nationalist, too. Isn’t that splendid? I think we’re all splendid, all we young people who believe in Scotland’s future and are prepared to work for it and fight for it if necessary. I should love another war, though I couldn’t bear to see people killed, of course. But I think I could do anything for Scotland, I’m so enthusiastic about Nationalism, though my husband says it’s all rubbish.

At this point Magnus felt a heavy hand on his arm and Mrs Dolphin said to him, ‘There’s a gentleman here who’s very anxious to meet you, and he’s got to go in a few minutes to catch a train. So will you come and talk to him now?’

As soon as they were out of earshot of the vulpine lady she said: ‘I heard that creature shouting away at you and I knew you couldn’t stand her blethering much longer, so I just came to rescue you. But it’s true enough there’s a man wanting to talk to you, and that’s Mr Macdonell, who’s a Vice-President of the Party, and a good man too. He’s got his head screwed on the right way. He’s not like some of these others who talk as if they’d taken a dose of castor-oil and couldn’t help it.’

George Macdonell was a short, red, freckled young man on whose very youthful features sat a premature look of statesmanship. He had a serious manner and a deep ringing voice. He said, ‘You made the only sensible speech this evening, Mr Merriman, but you mustn’t say things like that again if you’re going to be a politician. You must learn tact. You can’t afford to alienate people if your primary aim is to obtain their votes. You can frighten them or flatter them, but you shouldn’t tell them the simple truth unless you’ve calculated its effect.’

‘I’ll be damned if I turn Socialist or pacifist for any quantity of votes.’

‘If you were contesting an election you would have a large number of Socialists in your electorate, and it would be foolish to offend them.’

‘You’re not one of them are you?’

Macdonell laughed shortly. ‘No!’ he said.

Magnus began to feel that this young man was a new Machiavelli, and his admiration grew large. He asked several questions, and Macdonell’s answers were all very satisfactory. Magnus’s spirits rose, and when the guests began to go he shook hands warmly with his new acquaintance and swore they would stir Scotland yet.

He looked for Frieda and found her listening, though without sympathy, to Meiklejohn, who was trying to persuade her of the benefits of Nationalism.

‘Take me out of this crazy joint,’ she said, ‘and for God’s sake, don’t say another word about politics. I’m sick to death of them.’

They said good-bye to their host, but found it difficult to tell him how much they had enjoyed his party because of the vigorous music played by a piper at his very elbow. Magnus asked Meiklejohn to come with them to his flat for a last drink, but Meiklejohn, with the excuse that he had work to do, refused. Such rejection of conviviality was unusual in him.

Frieda explained: ‘I suppose I wasn’t too polite to him about this darned Nationalism. He will talk about it. I’ve been out with him a couple of times, and he’ll talk of nothing else, and the whole sad story just gives me a pain.’

‘That depreciates you, not Nationalism.’

‘Now I ask you, how can a movement be worth anything that depends for its existence on a crowd of nuts and bums and high-brow poets and side-show exhibits like we saw tonight?’

‘Every revolution, from Christianity downwards, has begun by attracting the more volatile elements of society.’

Frieda said with considerable surprise, ‘Now that’s the very thing that Meiklejohn said when I asked him the same question. What do you make of that?’

Magnus thought it unnecessary to tell her that he himself had first heard this plausible explanation from Meiklejohn and answered, ‘There’s nothing to prevent a problem being correctly solved by more than one person.’

‘Say, are you religious as well as Scotch?’

‘No, just superstitious.’

‘Honest to God? You really are? Do you believe in witches and that sort of thing?’

‘Certainly I do. My great-grandmother, in Orkney, was a rather well-known witch.’

‘No, I’m serious, because I was once scared out of my life, or darned near it, by a witch. That was in York County, Pennsylvania. I’d been hitch-hiking, and I’d got a lift from a drummer who was going to see his girl. Well, it was about ten o’clock of a pitch-black night when we reached the village where she lived, and the wonder is we didn’t go right past without seeing it, for there weren’t more than five houses on one side of the street and three on the other. It was the darned-loneliest place I ever struck, and the wind was howling like a wolf and lifting the snow off the road—it was in January when this happened—and the whole country seemed empty except for those five houses. And there wasn’t so much as a light in any of them. But the drummer was a good guy and he went with me and knocked on the door of one of them, and presently a woman came down. She didn’t seem too pleased to see us. She was Pennsylvania Dutch, and kind of stupid. But after a while she agreed to let me come in and to give me a bed for the night, and then the drummer went off to his girl’s home across the street. He didn’t want to take me there till he’d had a chance to explain about me, and tell his girl I was only someone he was giving a lift to. So he said good-night and promised he’d come and see me in the morning, and bring his girl with him. But he was back long before that. Well, the old Dutch woman began to make up a bed for me in the parlour, and while she was fixing it she asked me who I was and where I was going, and so on. She asked me who was the guy I was with, and where he was going. So I told her he’d come to see his girl. ‘What girl is that?’ she said. She spoke pretty bad English. It sounded as though she was grumbling at something all the time. I said the girl’s name was Elsa, and that gave the old woman a surprise. You could see she was upset. She stood still for quite a while, with a blanket in her hands and her mouth half open. Then she said, ‘Elsa, Elsa!’ and something in German, I don’t know what. So I asked her if anything was wrong with Elsa, and if she had a nice home, and if the family were nice. The old woman got all excited at that, angry, and yet kind of scared as well. Oh, they were a very nice family, she said, but the way she said it you just didn’t believe it. “Her father is a carpenter,” she said. “He makes coffins, but he don’t make them too good.” Well, just then there was the hell of a knocking at the door, and there was my drummer back again. He was white as cheese, and he was so frightened he couldn’t speak. I guess his mouth was too dry. He was shaking all over, and when he tried to say something he just made funny noises. Then he sagged at the knees and slumped down, dead-out in a faint.’

The story was interrupted by their arrival at Magnus’s flat, and Frieda postponed its conclusion till Magnus should have found decanter and glasses and they might be comfortably settled. She took off her hat and coat and stood before a mirror, patting her hair.

‘Aren’t you going to light the fire?’ she asked.

‘I can’t find any matches.’

‘Look in my bag: there’s some there.’

Magnus opened the bag that she had laid on a table and discovered a magpie’s nest of small articles: there were two keys, a powder-box, some loose change, a cigarette case, a lipstick in a metal container, a pocket-comb, several letters and, most remarkable of all, a tooth brush. It was not a new brush that she had just bought, for the bristle tips were faintly tinged with some pink dentifrice. The reason for its presence among articles of strictly daytime use was not immediately apparent, but after no more than a moment’s thought Magnus, with characteristic optimism, came to a feasible conclusion.

Frieda, turning away from the mirror, spoke sharply: ‘Here, give me that bag! I’ll find the matches.’

‘I’ve got them,’ said Magnus, and put the bag down. Frieda looked at him suspiciously. He wasted no time but clipped her in muscular arms, kissed her enthusiastically, and pulled her on to a sofa. She resisted with a brisk display of energy, wriggled in his grasp, turned her head this way and that, gasped fiercely a command to let go, an adjuration to stop, and then relaxed, and then grew fierce again—but not now to thrust away, for now she drew him to her, holding as strong as he did, nor waited passive to be kissed, but foraged on her behalf.

Presently Magnus said: ‘You’re going to be late tonight.’

‘You bet I am,’ she answered.

‘What will Uncle Henry say?’

‘Uncle Henry’s gone to London, and Aunt Elizabeth’s gone with him, and they won’t be back for a week.’

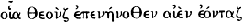

Two or three hours later Magnus woke from dreaming of a large Dutchwoman who was spreading bedclothes in an empty coffin. He turned over, remembering Frieda’s unfinished story, and immediately the terror of the dream vanished beneath the occursion of pleasure. Like rocks before a flooding tide it disappeared, and over his senses an army of delight marched with music. Frieda, still sleeping, lay beside him. They had left a table-lamp burning, for she had none of that modesty which blemish and physical imperfection so respectably beget. She had undressed with as much pleasure as the owner of one of Rembrandt’s great pictures will draw a curtain and show to a chosen visitor that masterly drawing, that magical light, the gleam as indescribable as that which glorified the visible form of the gods:

And as use makes perfectness, so Frieda had achieved it by implementing her beauty with the grace, dexterity, and cordiality of her love-making. Here, thought Magnus, is the perfect mistress, and suddenly he chanted:

Io Hymen Hymenaee io,

Io Hymen Hymenaee!

But then he frowned and muttered a rude objurgation, and grew unquiet with vexation to remember he had once quoted that marriage-hymn while Margaret Innes lay beside him: and he had deliberately thrust Margaret out of his memory, for she had disappointed him and made a fool of him by spoiling a fine romantic image with the disclosure of reality. In a variety of ways it was unpleasant to be reminded of Margaret, for he was uncomfortably aware that he had not treated her very well, and to recall the extravagant protestations he had made to her caused him exquisite embarrassment.

Frieda stirred in her sleep, stretched, and woke.

‘Heartsease!’ said Magnus. ‘Honeyheart, beatitude! Wake up and tell me the story about the witch.’

‘The hell I will! I want to go to sleep.’

‘Wake up! I want to hear about the witch.’

‘Because you’ve got a family interest in them? I bet your grandmother didn’t behave like this one in Pennsylvania.’

‘It was my great-grandmother. She was my great-grandfather’s third wife, and she ill-wished the first two so that they died in childbirth. Then she married him.’

‘Don’t put ideas into my head, or I’ll marry you.’

‘You’ll do no such thing. I’ll cosset you and comfort you and bewilder you with love, but I’m damned if I’ll marry you. I’ve got Blake’s ideas about marriage: “Whoso touches a joy as he flies, lives in Eternity’s sunrise, but whoso binds to his heart a joy doth the winged life destroy.” Besides, I think you’re a witch yourself: they milk from the moon a shining white liquor, as white as you, and sometimes a pool of it is found in high moorland places, and to touch it will drive a man mad.’

Magnus invariably grew loquacious when he was in high spirits, and he continued to talk enthusiastically about witchcraft and to relate several Orkney superstitions, one or two authentic, but the rest of which were his own invention. By and by Frieda said, ‘Say, did you wake me up to hear your stories, or to hear mine?’

‘I’m sorry! I was only filling in time till you were ready.’

‘Well, if you want to know what happened, I’ll tell you. But it’s no joke: remember that! I was scared to death at the time, and I’m still scared when I think about it. Well, I told you about the guy coming back, and then fainting? The old Dutchwoman undid his collar and I rubbed his hands, and presently he got better, and as soon as he could sit up he wanted us to go back with him to his girl’s house. The old woman said no, she wouldn’t move a step outside the door, not at that time of night. But Hyson—that was the drummer’s name—he was just about frantic to go, though he could hardly stand by himself. So we talked some more to the old woman, and by and by she got a shawl, grumbling all the time and kind of frightened too, and out we went. The wind was blowing the snow up in a little vortex, and it was so cold it took your breath away. I don’t know if it was owing to that or to something else, but just outside the other house I got a feeling as though I couldn’t go in, no, not for anything. The old woman walked right in, though, and I thought I’d better follow her. Then we found the girl. She was lying on her bed, with the covers rumpled back and her nightgown torn, and she’d queer torn marks, some of them like tooth-marks, on her arms and breast. She was dead all right. Hyson just put his head in the covers and began to cry, and the old woman stood there shaking all over. Well, I thought I’d better see if we couldn’t get some help, but there wasn’t another soul in the house. So I asked the old woman what we should do, but she’d only speak German and I don’t know what she said, till she began to talk about the girl’s father, who was a carpenter. She seemed to think it was all his fault because he didn’t make his coffins out of good wood or screw down the lids properly. I didn’t see what that had got to do with it, but Hyson looked up and screamed, ‘Witches, you fool! If a witch hears of a corpse that isn’t properly buried she’ll come and tear it to bits with her teeth. They’re witch’s marks on Elsa!” Then he cried again, sobbing and kind of holding his breath. It made you feel cold all over, and sick, too, to look at those marks after hearing that. I asked the old woman where Elsa’s father was now, but she wouldn’t answer. Hyson stopped crying, too, and just sat quiet. We all sat there, saying nothing. We sat there till morning, and we were so stiff with cold we could hardly move then.’

Magnus felt a pricking of the flesh and his blood seemed to run more chilly in his veins as he listened to this unpleasant story, and when Frieda spoke of that frozen room and the witch-marks on Elsa’s body he even grew a little frightened of her—though he would indignantly have denied this—for she had sat there and seen the strangely torn flesh and carried as if by infection some tinge of the horror with her. But he made an effort to judge the story with common-sense scepticism and asked, as casually as he could, ‘And what happened the next day? What was the explanation of the girl’s death?’

‘God knows,’ said Frieda. ‘I didn’t stay to hear. I said good-bye to them as soon as it was light and went out and stopped a car that was going to Harrisburg, and I got a ride as far as that. I’d had enough of that darned village. Wild horses wouldn’t have drawn me back.’

‘But what do you think was the explanation?’

‘Say, I thought you believed in witches? And now when I tell you a story about them you ask me to explain it away. That doesn’t seem reasonable to me.’

Magnus was very unhappy. His exultation, that had risen like a wave, had fallen like a wave, and when Frieda’s voice grew sharp to rebuke his scepticism he felt a small but definite tremor of fear. He remembered inopportunely a verse about strange women whose feet go down to death and whose steps take hold on hell, and he recalled a story about a succubus, and he wished that he had lived more virtuously and thought hopefully of the rectitude he would henceforth pursue. The lamplight shone white on Frieda’s shoulder, and the discomforting thought returned of the witches’ virus, that pale and shining fluid which is sometimes found on high heaths and is poison. All the tales of horror he had ever heard, and even those that he himself had confected, assailed his imagination, and in his ears the old Dutchwoman muttered rumours of hex-men.

Presently Frieda, wearying of inactivity, said, ‘Well, there’s no use worrying about something that happened three thousand miles away,’ and approached him with tentative caresses. But Magnus could not strengthen his spirit nor rouse himself to respond, and the night, unflowering, dwindled bleakly to the dawn.