THREE |

LADY N. |

A Loaded Gun |

MARCEL PROUST SAID THAT THE REAL VOYAGE OF DISCOVERY IS not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes. I experience a slightly different version of this dictum practically on a daily basis, developing new insights through my patients’ eyes. None could claim a vision more penetrating and acute than Lady N. She was high-spirited and boisterous, with a rowdy, uproarious personality that sparkled with wit and humor, possessing an uncanny habit of connecting seemingly unrelated things through common sense, extreme intelligence, inimitable humor, and pure and simple intuition. And most importantly, she had a blazing, sizzling passion for life writ large all over her massive five-foot, ten-inch frame.

Aged sixty-two, Lady N. swept into my clinic for her first visit in 2008 with this farcical, preposterous announcement: “FYI, I have been extremely anemic for at least twenty-five to thirty years, if not longer,” she told me. “I also believe strongly that there is a genetic component to my MDS.” She went on, “As you know, my father’s sister’s first child was born with no marrow in his bones.” Although she had been anemic for a long time, her MDS had not been diagnosed until just before I met her. The first few years were not too hard, as her diseased cells were marked by a deletion in the long arm of chromosome 5. This special subtype of MDS is associated with slow progression, a longer survival, and an especially good response to Revlimid, a derivative of the once-infamous drug thalidomide.

BACK IN 1999, I had personally prescribed thalidomide for Harvey, one of the first lymphoma patients ever to receive the drug on a compassionate basis.

When Harvey’s cancer started manifesting a series of sudden, startling, painful paraneoplastic syndromes, we knew some form of therapy was now inevitable. Around this time, I heard data presented by an oncologist at a national meeting who had tried thalidomide in patients with lymphoma and had seen sporadic benefits. I immediately felt this could be a safer alternative for Harvey, who was still reluctant to start chemotherapy. I told Harvey I thought it was worth a try. What did we have to lose—a few weeks? Harvey listened to me and was willing to go along with my suggestion. Needing reinforcement for such an experimental use of the drug, we visited Harvey’s primary oncologist in Chicago, Steve Rosen, a charismatic, deeply empathetic, kind, caring physician, a great friend, and the cancer center director at Northwestern. We reviewed Harvey’s treatment options. Chemotherapy. A different kind of chemotherapy. Steve listened to my case for trying thalidomide. He agreed to prescribe the drug. Backed by Steve, as well as Owen O’Connor, chief of the lymphoma service at Memorial Sloan Kettering, I was able to get the drug on a compassionate, one-patient protocol basis for Harvey from Celgene, its manufacturer.

We started Harvey on thalidomide at 50 percent of the recommended dose because of the toxicity I had seen in MDS patients. The results even with this reduced dose were spectacular. Within forty-eight hours of starting, Harvey’s facial edema started to melt visibly. By week’s end, the pitting, uneven, grotesque puffiness had entirely disappeared, and his fine features reappeared.

LADY N.’S BLOOD counts eventually dropped, requiring intervention. As hoped, she responded well first to the red cell–stimulating hormone Procrit and then to Revlimid. The anemia improved beyond expectation, and she had an excellent quality of life, caring for her many cats, taking long drives visiting her numerous best friends, shopping and dining with her ninety-nine-year-old mother, and generally enjoying life to the full.

Lady N. would come to clinic for follow-ups regularly and endeared herself to everyone she encountered. Her openness, loud and hilarious remarks, self-deprecation, and a poignant concern for—and astonishing ability to recall—others’ personal lives made her easy to like. Another unique quality was her matchless ability to communicate with the younger individuals who inevitably follow me in clinic. Whether they were high school students interning during summers, doctoral candidates writing dissertations on MDS, or fellows training in hematology, she would inquire about their backgrounds in a few sentences and then proceed to engage them through anecdotes and personal stories that were somehow tailored for their individual needs. I can recall numerous young fans, Matt Markham in particular, who kept in touch with her long after their rotations with me were done. Such was her attraction, such her charm.

She was a cat lady. Lady N. and her late husband toured with their beautiful feline army throughout America and Europe, earning admiration, winning awards, breeding and showing oriental shorthairs, amusing the clinic staff with endless, entertaining stories of her various award-winning trips. She created a memorial fund at Cornell University Feline Health Center dedicated to improving the care and well-being of cats in honor of her favorite cat, William. Lady N. was also an accomplished photographer of nature and of birds. She participated in research projects at the University of Vermont, including a study of the Indiana bats of East Dorset. She was a member of MENSA, played tournament bridge and chess, and was a natural with computers. She greatly enjoyed sharing her vast resources of knowledge in diverse fields and astonished her listeners by citing extraordinary facts during ordinary conversations. I adored her.

Lady N. was constantly examining her past to determine the root of her MDS—wondering if the kerosene heaters in a cabin where she spent holidays as a child might have contributed to her condition—and was always picking my brain for more satisfying answers than Google was able to provide about her future. She was especially eager to learn where the latest research on targeted therapy was heading. As I would describe some new drug we were testing in a phase 1 or phase 2 trial, she would become quite excited. “I am counting on you, my dear, dear friend, to make sure that I have at least another ten, if not twenty, years. Between the two of us and your colleagues, I am counting on it!” And she told me several times, “I want to be there when you make MDS a chronic disease like AIDS is now.”

And then the inevitable happened, and she stopped responding to Revlimid. That left her transfusion dependent. Even as she was being pumped full of red blood cells from matched donors, her wicked sense of humor was ever present, and she would send me weekly cartoons that would make me smile or burst out laughing in the middle of clinic. Eventually, she was started on chemotherapy with Vidaza. It was not a pleasant experience. As the Vidaza continued into the fourth and then fifth month without any relief in the frequency of blood transfusions, an unexpected new symptom crept in. Lady N. began to experience inexplicable fatigue. She would wake up in the morning after an eight-hour sleep feeling like she had been pulling a cart all night. She was totally worn out by the simple act of brushing her teeth; washing and blow-drying her hair required at least three intervals of rest. Her arms felt like lead. She pumped herself full of coffee and took Excedrin and then Ritalin to shake herself out of the doldrums. Nothing worked. Week after week, she sat across from me in clinic and recounted the list of chores she had been unable to complete. We tried hyper-transfusing her with blood, maintaining her hemoglobin above 10 Gm at all times (the normal range is 12.5–16 Gm). Even she was perplexed by the profundity of exhaustion. She used to feel better when the hemoglobin was 7 Gm than she did now at 10 Gm. Ultimately, after ruling out all possible causes like nutritional deficiencies, thyroid dysfunction, drugs causing a side effect, we had to admit that she was suffering from a paraneoplastic syndrome.

We stopped the Vidaza, and that brought her temporary relief. She sent me the following note:

Lately I’ve had so many transfusions I feel like changing my profession to “vampire” on hospital forms.… And as I like to tell people, I’ve done so much “blood doping” that I probably wouldn’t be allowed to watch the Olympics on television.… Ok I jest, but I feel so much better. Gone is the peripheral neuropathy, the hot flash-like fevers at night, the dizziness and the mental foggies and a whole host of unpleasant side effects not the least of which is that when I’m on chemo I’ve felt like I’ve lost at least 50 IQ points.… It’s nice to have them back.

We began to relax, celebrating her temporary deliverance from the deeply discomfiting symptoms, knowing full well that it would not last forever. She would storm into clinic, blowing kisses, handing out utterly unhealthy delights—cookies and doughnuts—high-fiving nurses and arguing with the receptionists, happy to be something of her usual unusual self once again. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

We continued to treat Lady N. symptomatically, but she was visibly getting worse, requiring more transfusions of blood and now occasional platelets as well. We became quite worried when Christmas 2014 rolled around and she told us that she was going to drive her mother to Vermont to visit family and friends. She tried to assuage our concerns about her “running around in these days of the new normal.” “It just takes planning,” she told us, “sort of like a military campaign.” She insisted anything she could do sitting down, including driving a car, wasn’t a problem—“that is, unless my hemoglobin is really tanking and my mind starts to get fuzzy.” She did admit that “the vertical activities,” like walking from her car to a shop’s front door, do “have to be planned for rather carefully.” And she had plans, including favoring stores where she could park near the entrance and lean on a shopping cart, but they were all clearly a willful denial of reality. Her absolute refusal to see what stared her in the eyes, her persistent demands for solutions from me, and her outrageous expressions of supreme confidence in my abilities in particular and of science in general to provide a cure for her left all of us involved in her care a little unsettled.

How someone with her level of high IQ, a member of MENSA, an extremely well-read and well-traveled woman of Lady N.’s extraordinary caliber managed to steadfastly, categorically, and decisively resist, ignore, and reject out of hand any acceptance of her looming mortality remains one of those perplexing things about humans that make us such complicated creatures. Since I had recently gone through the Omar debacle, it was only natural to compare Lady N.’s responses to her cancer with his. At thirty-eight, Omar, a brilliant young professor, distracted himself by obsessively researching treatment options and remaining hopeful until the end, yet at some intangible level, I sensed in him a silent, deeply melancholic prescience of impending doom. From the moment of diagnosis, he existed in a liminal space, suspended between life and death, waiting impotently, not knowing, perched on a threshold, unable to cross over or retreat, powerless to fully explain his own location. There was a delicate perishability about him, an unspoken despondency even as he ostensibly engaged in carefree celebrations of living. At other times, like the magician Prospero, reminding his daughter of the brevity of mortal life in The Tempest, Omar, too, seemed prepared to declare an end to the revels, “We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.” The aesthetic dignity of Omar’s acceptance coming from inexplicable, peculiar, deep crevices of his psychic interior contrasted sharply with the flamboyant refutation of reality by Lady N., her obsessive postures of waiting, her perpetual expectancy, the flows and eddies of her piercing, scorching desire to live at all costs.

Celebrating her mother’s hundredth birthday provided Lady N. with further reassurances of an inherited, robust, indestructible genetic makeup and presented her with a model to emulate: “The woman is a machine! She is also extremely stubborn! In many (but not all) ways, I’d love to grow up to be just like her. Especially to be one hundred years old, mentally together and well enough physically to be able to live by myself and do for myself the way she does. I mean, the woman is truly remarkable.”

Around this time, Lady N. informed me that she had developed a whole new philosophy about her disease and how to cope with it. I asked her to write it down for my other MDS patients:

My mantra:

I am NOT my cancer.

I am not a “victim” because I have cancer.

I am not a “hero” because I’m fighting cancer.

I have no contract with life that will stand up in court. I could be crossing the street on my way to the garage to get my car and get nailed by a garbage truck.

I will NOT allow people to marginalize me because I have cancer. (I find that people tend to marginalize you once they find out that you have cancer.)

She also wrote down what the worst part of having MDS was, and how she responded. For her, cancer was like “climbing a mountain while wearing a knapsack and with every step it is as if someone is putting another brick or two in the knapsack. It is truly remarkable how much heavier and weaker I feel with each upward step. How do I deal with this? I try to get the same satisfaction from climbing a flight of stairs as I used to get from climbing a glacier, a mountain or the Alps as I did when I was a kid.” And then she advised others about how to choose which mountains to climb:

I have only a certain amount of energy each day and if I choose to expend that energy going out for a drive or for lunch in a restaurant or to the movies instead of making the bed or picking up or doing the laundry, that’s fine. And if you come to visit me and disapprove of the mess or the unmade bed or unwashed dishes you have three choices: 1) you can ignore the mess, 2) you can clean it yourself if it really bothers you or, 3) you can leave.

LADY N. RETURNED from Vermont and almost immediately afterward presented to the ER with a high fever, shaking chills, wild episodes of sweating, severe nausea, and uncontrolled vomiting. She was on the verge of septic shock. We admitted her to the hospital. The routine exhaustive workup for infections followed. Intravenous treatments to cover every possible pathogen were initiated. Again, as with the majority of such patients, no source for the fever was discovered. She began to deteriorate rapidly. Each morning, I stopped by to see her in the hospital. She looked at me wistfully from her bed, complaining about the shower and imparting acute asides. “The spaghetti they serve is so fake in this hospital,” she said. “I call it impasta.” As we tried to control the unidentified infection, presumably a fungal pneumonia, her white blood cells stopped maturing and started a steady, ominous climb in the blood. The MDS was transforming into acute leukemia in front of our eyes.

Talking to Lady N. as she fought the sepsis, I felt seriously deficient in my ability to explain the many paradoxes and uncertainties we were dealing with. In her case, the telltale signs of impending disaster had begun appearing a good six months before all hell would break loose. Back then, the leukemia cells brewing in her bone marrow were only just starting their hostile takeover and were still manageable in quantity. A new cytogenetic abnormality, along with a higher percentage of immature cells, was detected in the marrow. When I told her, she paled. “Okay. I guess this is not the news I was hoping for.” But true to her motto—“Never give up—never give in!”—she said, “Why not treat me aggressively now? You always say, Dr. Raza, that the time to fix the roof is when the sun is shining. Not only is the sun going down rapidly for me, leaks are already appearing. How about doing something definitive now? Use me as your guinea pig. Try whatever you want. I trust you and will do exactly what you tell me.” She was absolutely correct in demanding me to act then, a time when the leukemia was just starting to rear its ugly head. Isn’t that why I had turned my attention to studying MDS in the first place—to find the leukemia early and treat it with a curative, preventive intent?

The problem for Lady N.—and for all cancer patients—is that unless the cancer presents early as a solid mass that can be surgically removed, there is no definitive, curative treatment that can be safely given to eliminate a small number of circulating cancer cells. All we have as treatment is chemotherapy that would end up destroying more normal cells than the few abnormal ones. In the presence of full-blown leukemia, chemotherapy is worth giving because the majority of cells in the bone marrow are leukemic. It is like saying we cannot treat your common cold, but if it develops into a pneumonia, we can.

In the background of MDS, a clonal cell had mutated in Lady N.’s marrow, losing any capability of differentiation, remaining an immature blast, a cell whose entire existence consisted of unceasing cycles of doubling its DNA followed by mitosis. The only potential cure for her would have been a bone marrow transplant. This involves killing every last cell in the patient’s bone marrow, normal as well as malignant, and then trying to restart the empty marrow with fresh cells from a matched donor. Destroying the bone marrow carries with it so much toxicity and such a high risk of death that the procedure must remain limited to a select few, handpicked younger MDS patients. Lady N. was not a candidate for a bone marrow transplant due to her age and multiple comorbidities with suboptimal function of heart, lungs, kidneys, and liver.

At that point, almost six months since we first detected the earliest signs of transformation in her marrow, sepsis was complicating a rapidly advancing leukemic takeover in her body. Treat her for the infection alone, and the leukemia would get her. Treat the leukemia with the same old chemotherapy regimen and she would die faster from the suppressed, empty marrow, unable to hold the infection back. No matter what we did, her chances of survival would not improve. It was now a battle between the devil and the deep blue sea.

THE STRATEGY FOR treating acute leukemia, followed for the past fifty years, is to kill as many abnormal cells as possible with a round of aggressive “induction” chemotherapy. This requires patients to be admitted to the hospital for several weeks, during which they receive what is known as the 7+3 protocol: seven days of a drug called cytosine arabinoside, or cytarabine for short, and three days of the drug daunorubicin. These cytotoxic agents kill both the leukemia cells and all other rapidly dividing cells in the body, leading to the three most common side effects associated with chemotherapy—killing hair follicles, leading to baldness; killing cells in the gastrointestinal tract, leading to nausea and vomiting; and killing normal residual bone marrow cells, causing low blood counts and making patients susceptible to infections. Because those cell types proliferate at breakneck speeds, they are most sensitive to destruction by the chemotherapy. The bone marrow alone makes close to a trillion cells every twenty-four hours in a healthy adult. Once chemotherapy empties out the bone marrow, a period known as aplasia, it takes two to four weeks to recover. During this interval, patients end up with life-threatening infections requiring aggressive intravenous therapy with multiple antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral drugs. If the marrow recovers with less than 5 percent leukemia cells, it is a complete remission, or CR. This is indeed cause for short-term celebration.

The problem is that a CR by itself is not sufficient. In a bit of mathematical medical jargon, one round of 7+3 only destroys several “logs” of leukemia cells (where each log is a reduction by 1/10, so three logs would mean 1/1000 of the original leukemia cells). If the patient is left untreated after this, even when the bone marrow shows no microscopically recognizable leukemia, the disease relapses. In order to “consolidate” the CR, repeated rounds of 7+3 or one of its variations must be administered in cycles. Because the human body can only tolerate a certain amount of cytotoxic assault at one time, a cycle is generally a month long with five to seven days of chemotherapy followed by a recovery period of two to four weeks. The patient is sent home briefly and readmitted for the next cycle within seven to ten days. When I started my training in oncology in the early ’80s, we did some of the pioneering trials to determine the optimal number of “consolidations,” comparing three, four, and eight follow-up, or postinduction, chemotherapy cycles. Eight was clearly too much; I recall only a handful of patients who completed this draconian prolonged torture. Today, two to four postinduction cycles are the standard.

The “hope” is to reduce the number to such a low level that the patient’s own immune system can somehow deal with the “minimal residual disease,” or MRD. Multiple technologies have evolved to detect one in a million or even one in a billion abnormal MRD cells. Even though we can detect those cells, we don’t have anything more effective to offer than 7+3 to kill them. Using the protocol again, however, would kill billions of normal cells while having a good chance of not killing those rare leukemic ones. The strategy fails in about one-third of patients, either from the beginning, because the dominant leukemic clone is entirely resistant to the 7+3 and there is no complete remission to begin with, or because the MRD causes relapse of the disease.

It is hard to believe that since 1970, no better strategy has emerged. I remember hearing a talk in 1982 at Roswell Park when a visiting professor said, “We know very well that our children will look at us in disbelief and say, ‘You gave what to your cancer patients? Chemotherapy? Were you out of your mind?’” Thirty years and many, many children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren later, we are still doing the same. Just having to repeat the same conversation, the same statistics, and the same list of side effects to hundreds of patients a year for the past forty years is embarrassing and deeply depressing.

Had Lady N. lived to 2019, she might have responded to a new drug called luspatercept. Luspatercept was not developed to treat MDS patients. Like most successful cancer therapies, it arrived by their bedside purely by serendipity, developed for one indication, found to be useful for another. Luspatercept traps molecules that would otherwise bind to receptors on the surface of cells; when something is bound to those receptors, they initiate a signal that is important during the formation of bone. Overactivity of this pathway can lead to loss of bone. In patients with multiple myeloma, bone can be eaten away, resulting in creation of holes known as lytic lesions. This class of drugs was developed with the hope of blocking that signal and thereby reducing the number of lytic lesions in bones. When these were tried in healthy volunteers and in multiple myeloma patients, the researchers running the studies noted that the recipients’ hemoglobin sharply increased, often to dangerous levels, ratcheting up so high in some cases that the patients had to undergo bloodletting. The researchers shifted course, and the focus was redirected to treating anemia instead. Enter MDS.

A phase 2 trial of luspatercept was conducted in Europe with encouraging results, particularly showing improvement in anemia of patients whose bone marrow contained ring sideroblasts, or early red blood cells where the nucleus gets surrounded by a ring of iron particles. It is an example of poverty in the midst of plenty. There is an abundance of iron (heme), but the red cell precursors are unable to combine this heme with globin to make hemoglobin. The ring sideroblasts cannot proceed without hemoglobin to become fully mature red blood cells. They drop dead, leading to anemia.

At Columbia University, we opened a multicenter phase 3 clinical trial of this agent in 2016 where 70 percent of patients would receive the drug and 30 percent would receive placebo. One such patient was Mrs. Fern Priestly; she had the ring sideroblastic anemia and was transfusion dependent, which were the two major eligibility criteria for the trial. Lady N.’s marrow also contained ring sideroblasts. The study was blinded, so we didn’t know whether Fern was receiving placebo or the drug when we began, but the side effects she experienced, especially early on in the trial, helped her put two and two together fairly quickly. “I know I’m not on placebo,” she told me, “because of how tired I feel after the shot every three weeks.” You don’t have to be a weatherman to know it’s raining outside. “But it is slowly getting better each time. I think my body is finally getting adjusted to it.” The study was for her, after nineteen years since being diagnosed with MDS, “the high point of the entire saga.” She was so excited about the stabilization of her hemoglobin count with one shot of luspatercept every few weeks. “I have literally gotten my life back.”

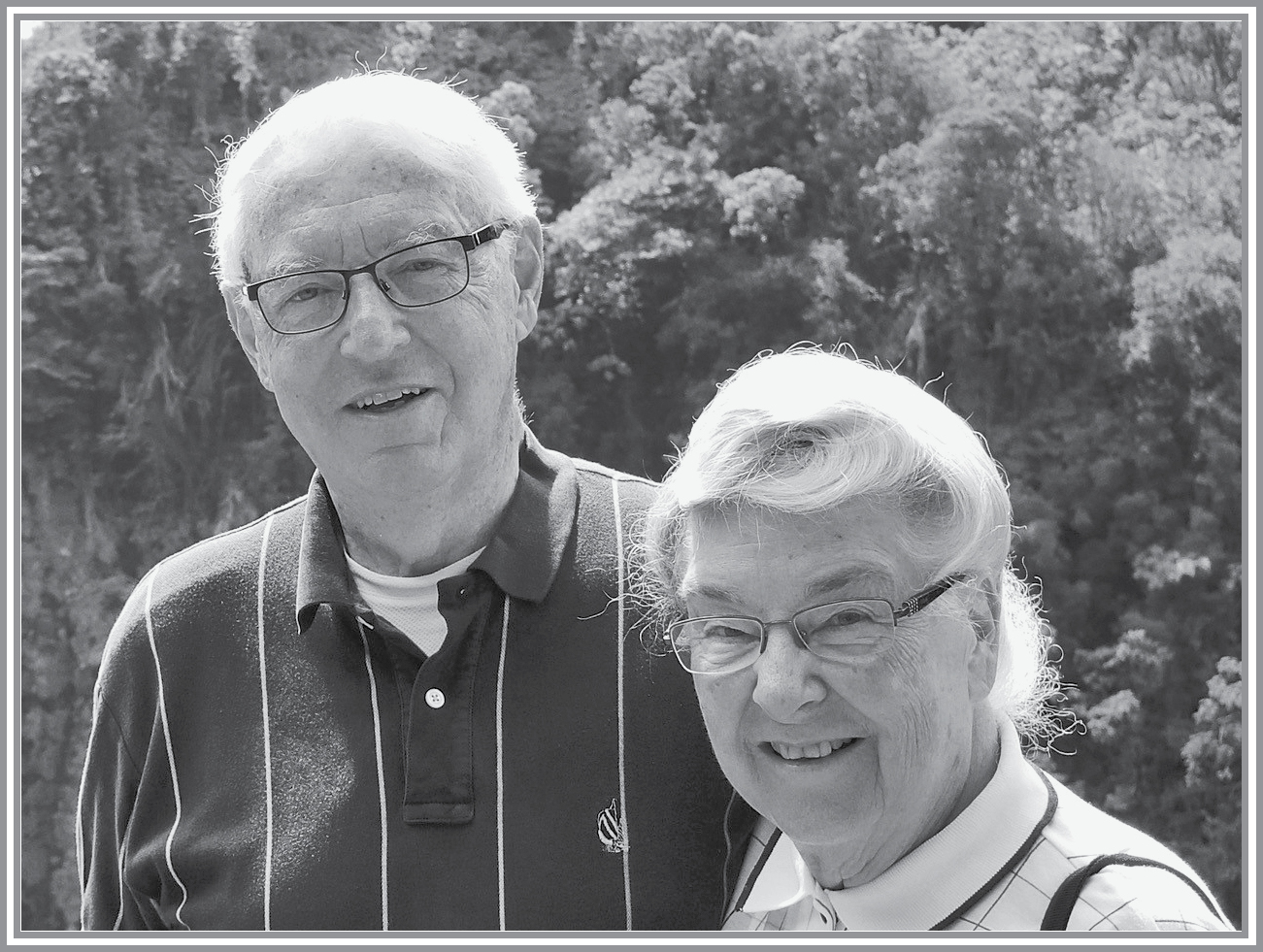

In one of the saddest, most tragic twists, dear Fern and her husband, Eldon Priestly, were involved in a deadly car accident. Fern died instantly on Sunday, August 12, 2018, and Eldon passed away from the mortal injuries he sustained, four months later.

How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable seemed all the uses of this world.

—HAMLET, ACT 1, SCENE 2

WHILE A PATIENT is participating in a study, every new complaint must be eyed suspiciously for possible relationship to the drug. Ultimately, the symptom may or may not be directly related, but extreme caution is necessary when new signs emerge under experimental therapies, as short- and long-term toxicities are inadequately known at the experimental stage. This is the price of novel drug trials. It became an issue with one of my patients on the luspatercept protocol.

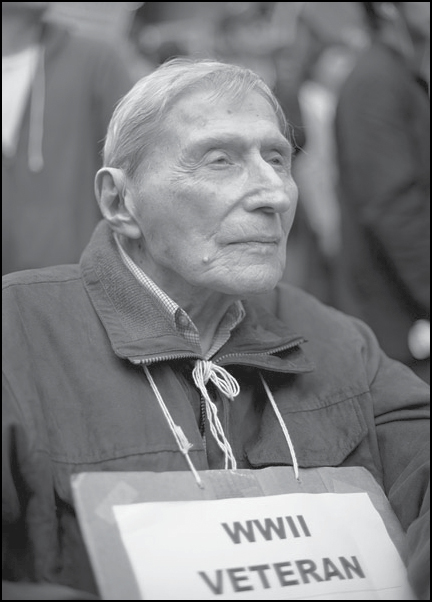

In 2011, I met a patient who became my ideal within a few meetings. Gerson Lesser, a tall, handsome, fiercely intelligent, generous, well-read, thoughtful New Yorker of Jewish descent, is a fellow doctor, teacher, and researcher. He came to see me with his lovely, equally intelligent wife, Debbie. We became close as we settled into a routine of regular clinic visits. He had been politically active for most of his life, beginning with marching for the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. He spent hours at Zuccotti Park, the center of the Occupy Wall Street protests in 2011. A photo of Gerson at the protest went viral, “putting the lie,” in Gerson’s words, “to Rush Limbaugh’s ugly remarks about the movement”: “These protestors who are actually few in number, have contributed nothing. They are pure, genuine parasites. Many of them are bored, trust-fund kids, obsessed with being something, being somebody. Meaningless lives they want to matter.” Gerson, at ninety-plus years of age, was out there with his walker every afternoon.

Once the medical part of his visits was over, we would spend twice that much time catching up on personal details, discussing politics and literature, science and music. He often brought me books he had just read or thought I would enjoy, I invited them to my apartment for book readings, and we went out to many dinners in lovely Manhattan restaurants. Gerson and Debbie have acquired a place in my heart reserved for only a special few. I feel incredibly fortunate every day for the opportunity my profession provides—bearing witness to some extraordinary lives, enjoying unparalleled, intimate glimpses into the most noble aspects of humanity. In the presence of such grace, all one can do is to be grateful.

By the time I first met him, he had been suffering from a chronic, slowly progressive anemia for eight years. Eventually, I put him on the luspatercept trial also. He, too, had a spectacular response, and his hemoglobin jumped by several grams to reach almost a normal level for the first time in over a decade, but he simultaneously developed shortness of breath on exertion. On the off chance that it was due to the medication, we withdrew Gerson from the trial. He promptly became transfusion dependent again and remains so to this day.

Even as both Fern and Gerson experienced dramatic responses to the trial drug, one died of a freak accident and the other could not continue, highlighting the uncertainties involved in the human condition. Nevertheless, luspatercept will be a welcome addition to the parched field of MDS therapeutics when it is approved by the FDA. The problem is that even when it is given to a hundred patients with ring sideroblast type of MDS, only thirty-eight will respond by becoming completely transfusion independent, while sixty-two will not, and based on experience so far, no one will be cured. It is discouraging to see that clinical trials today are designed in much the same way they were thirty to forty years ago. For example, it is clear that using ring sideroblasts as a marker to select patients for treatment was not good enough because not all patients responded. No serious attempt was made in the luspatercept phase 3 trial to understand why 62 percent of patients failed to respond and what is unique about those who did. We could have saved the pretherapy blood and marrow samples on the trial subjects and, once the outcome was known, compared the samples of responders and nonresponders by using the latest molecular tools. This comparison could have provided us with clues to preselect future potential responders. Equally disheartening is the attitude of the regulating agencies because they fail to demand more rigor from sponsors of the trial. What has the agency done to protect sixty-two of one hundred future patients who will have little response to luspatercept but will suffer the side effects of the drug and have to bear the exorbitant cost of therapy after the drug is approved? Nothing at all, unfortunately. The drug makers, on the other hand, expect a neat multibillion-dollar annual market for luspatercept between Europe and the United States once the agent is FDA approved. If I were younger, I would have concentrated more on the positive results for the 38 percent of patients on the trial rather than stress over the 62 percent of failures. Now that I am older, I cannot ignore the toxicities, nor the physical and financial tolls, that experimental medications take on patients. Even if Lady N. were alive today and tried luspatercept, there is no guarantee she would have responded and certainly no way of knowing for how long and at what cost of side effects. And once she stopped responding, her disease would still have progressed and killed her, either through transformation to acute leukemia or through increasing profundity of her cytopenias, causing the blood counts to plunge into irretrievable lows.

Such demoralizing news is not restricted to MDS and acute myeloid leukemia treatment. Vinay Prasad, a young hematologist-oncologist at Oregon Health & Sciences University, is a major critic of how the United States spends $700 billion on health care, identifying drug costs, conflicts of interest, poorly designed clinical trials for cancer drugs and diagnostics, and the fact that “more than half of all practiced medicine is based on scant evidence—and possibly ineffectual” as the major issues in the field. Prasad published an analysis of fifty-four cancer drugs approved by the FDA between 2008 and 2012. Of those fifty-four drugs, thirty-six, or 67 percent, were approved based on so-called surrogate end points—that is, on the basis of something other than a known effect on the tumor leading to improved survival. Indeed, follow-up over the next several years showed that thirty-one of those thirty-six approved drugs yielded no demonstrable gains in survival. What are we doing wrong? Perhaps the one-size-fits-all approach is the problem? Can we improve these grim numbers by custom-designing therapy to suit individual patient needs? Precision medicine.

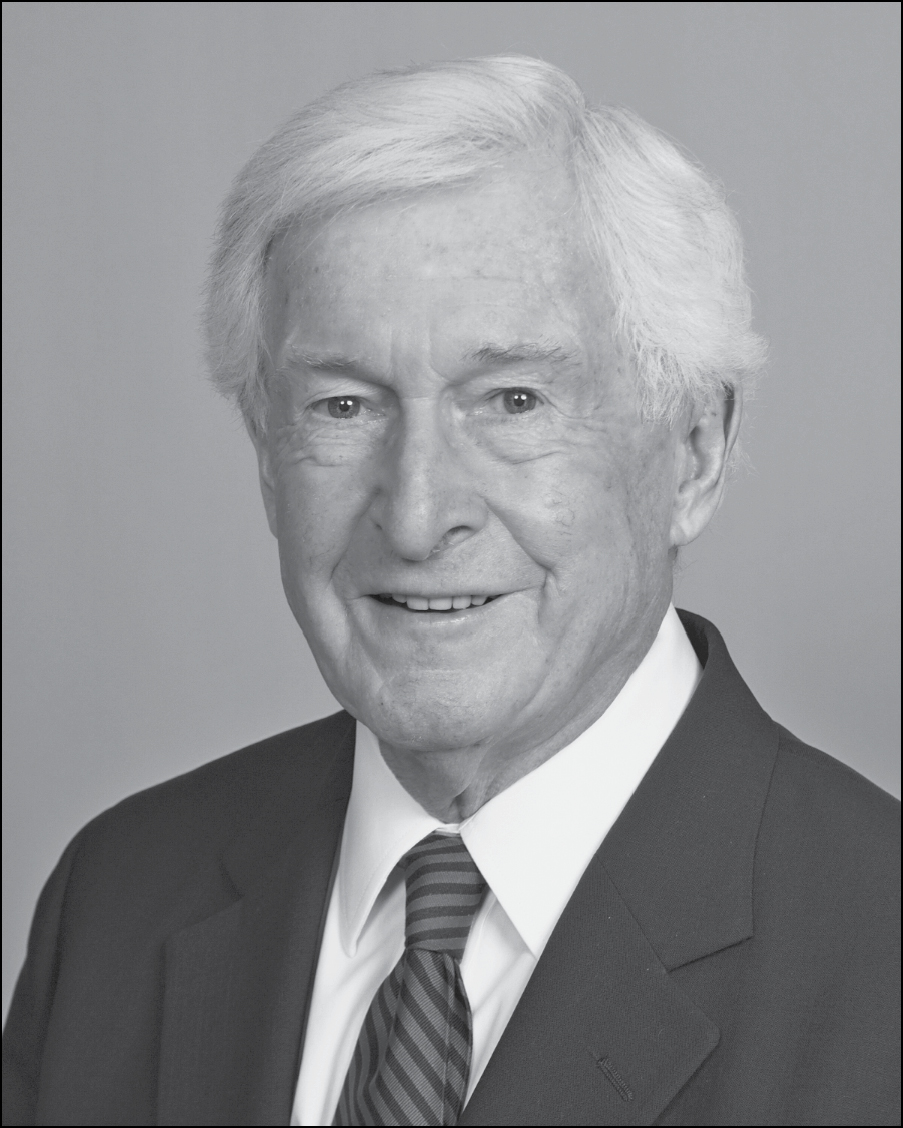

THE IDEA OF individualized therapy is attractive and logical on the surface. Take, for example, the drug Vidaza, which Lady N. received for six months to no avail. Other patients with MDS respond quite well to Vidaza, with the drug being effective enough that treatments—which can be debilitating—become less frequent with time. Mark De Noble, at eighty, was able to drive across the country with his wife after going on the drug in 2015: “It is February of 2019 now, and I continue to receive Vidaza for five days every six weeks and regularly visit Dr. Raza for my periodic bone marrow biopsies. My wife and I travel several times a year, mostly by car, exploring new places and visiting family and friends. At home, we enjoy hosting friends and family. Now that we’re retired, we volunteer once a month at a residential facility for fifteen troubled teenagers. As we all prepare a three-course dinner, we teach them how to prepare foods, handle kitchen tools, set a table, serve food, etc. Then we enjoy a delicious meal together.”

Mr. De Noble had an extraordinary response to Vidaza while Lady N.’s counts did not budge on the same drug despite half a year’s treatment. Under the microscope, their disease looked similar. In fact, Mr. De Noble experienced such complete and durable benefit from the drug that he earned a special moniker reserved for exceptional responders: unicorn. Traditionally, clinical trials of experimental agents are statistically powered to deliver response in a predetermined minimum percentage of patients. If the number fails to meet the end point, the drug is thrown out like the baby with the bathwater. This changed in 2012 as a result of a trial in which the drug everolimus given to patients with urothelial cancers produced overall dismal results in forty-four treated subjects but one of them showed a truly outstanding response. A deeper investigation into the reason for such exquisite sensitivity revealed the presence of unexpected mutations not previously associated with that type of bladder cancer, demonstrating once again the profound biologic variability within morphologically identical tumors. This one case led to the initiation of a pilot study, funded by the NCI, directed at identifying molecular features associated with exceptional responses. In the study referenced above, everolimus was the perfect drug for the exceptional responder, but was it worth having forty-four others suffer only the drug’s toxicities without any appreciable benefits?

The ideal situation would be to administer the drug only to preselected potential responders. Identifying predictive markers that allow for individualizing therapy by matching drugs to patients remains the treasured yet elusive holy grail of oncology. To what extent is this strategy being pursued? More than 90 percent of trials ongoing around the country make almost zero attempt to save tumor samples for post hoc examination to identify predictive biomarkers. Even in the NCI-funded study of exceptional responders previously mentioned, only genetic mutations were investigated as the single potential predictive marker. What if the reason for response was not a mutated gene but abnormal expression of the gene at the RNA level, or that it resided entirely outside the tumor cell, related to the microenvironment of the tumor? Why are we not making the required efforts in as comprehensive a manner as needed? Who is pushing this short-term agenda driven by the singular goal of getting a drug approved with alacrity as long as it meets the bar of improving survival by mere weeks in a few patients?

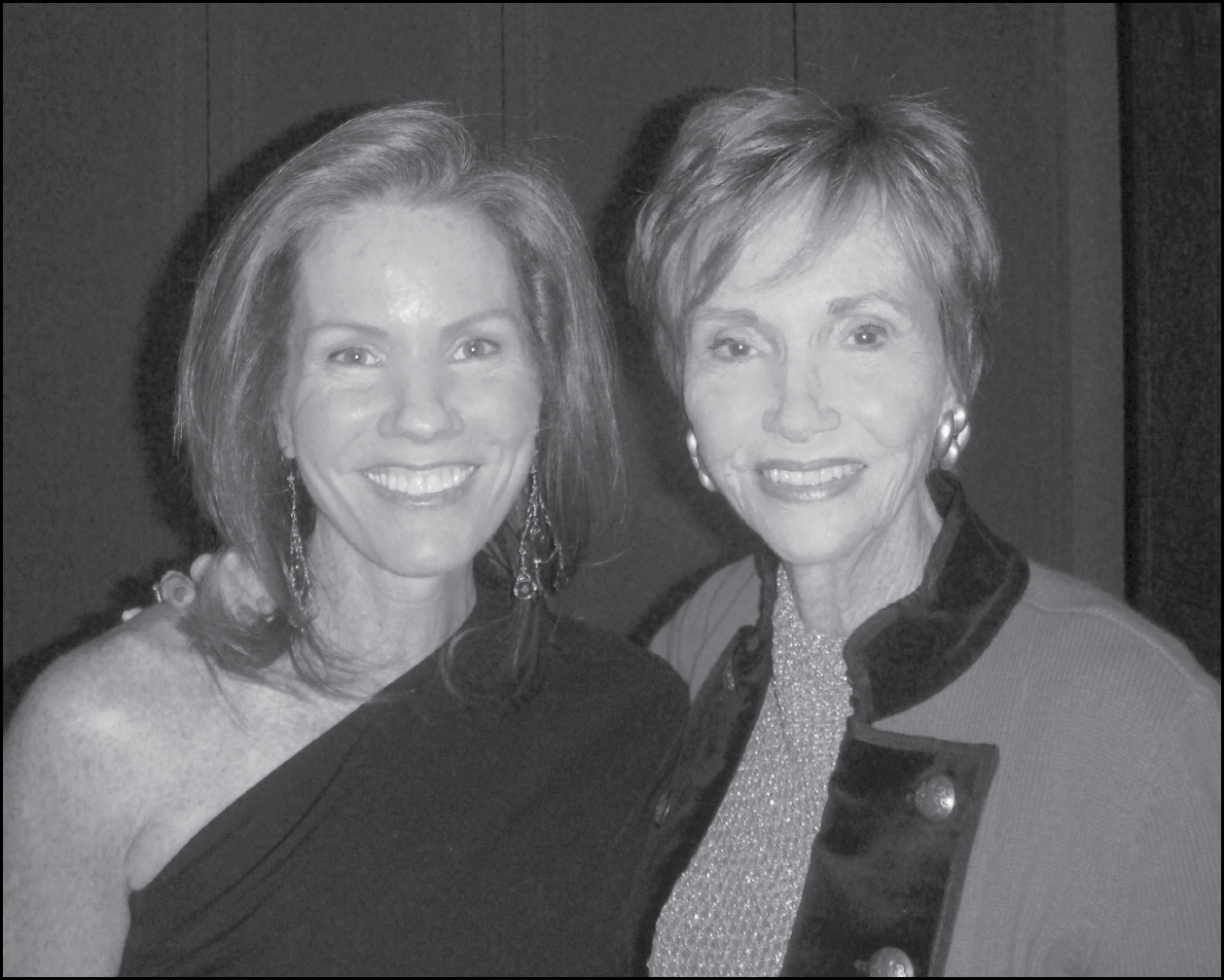

A patient with MDS that I became extremely close to over the years was Barbara Freehill. She had a lower-risk MDS that evolved to an overlap myelodysplastic-myeloproliferative neoplasm (MDS/MPN). I saw her every two to three weeks as she was steadily transfusion dependent. Her poise, dignified personality, gorgeous looks, and her incredible wisdom combined to make her one of the most amazing people I have been fortunate to take care of. We could talk about anything under the sun. I treated her for a long time with Dacogen and then Revlimid. She was under my care, seeing me two to three times a month for several years when one day she showed up without an appointment. My nurse came and told me Barbara wanted an urgent word with me. I went out to see her, and she could hardly breathe, so anxious was she. Her youngest daughter, thirty-nine-year-old Kendra Seth, was in the ICU. I will let Kendra tell you this shocking story:

I was admitted through the ER for a pain I was experiencing on my right side (I thought maybe I had pulled a muscle running). That pain quickly went from mild to excruciating. After a long night, a CAT scan revealed that I had a massive clot in my portal vein. The clot was virtually strangling all of the blood flow to my major organs. In order for me to survive, the clot had to be cleared as quickly as possible. After 3 failed surgeries & little hope for a plausible next step, my mom suggested that her doctor stop in for a “visit.”

I begged my mom not to… after the failure of my “best chance” surgery I was at an all-time low both mentally & physically. My body seemed to go into complete revolt, although I hadn’t eaten in weeks, I gained over 30 lbs in water weight virtually overnight. I couldn’t bend my fingers or toes, or even roll over—I was literally a prisoner in my own bed.

Mentally I just could not wrap my head around how a year ago I had successfully climbed Mt Kilimanjaro—how my life had changed so dramatically in a number of months. The last thing I wanted was another team of doctors that only asked the same questions and provided no answers.

And then I met Dr. Raza… at the time she walked through the door we were discussing my “best” option which was a 5 organ transplant. All I could think about was getting home to my husband & 4 young children so I was all for it—shows you how desperate I felt. When Dr. Raza quietly came in, she didn’t ask me all the usual questions, she spoke to me as a person, not a case—her humanity was immediately apparent. Dr. Raza suggested I be tested* for a mutation in the gene Jak2 and when that came back positive about 10 days later it was our first breadcrumb to getting me healthy.

(*Note: My colleague Joe Jurcic, who had been consulted as the hematologist on service, had noticed the high platelet count also, and had preempted me in ordering the test.)

The most dramatic feature of Kendra’s story is that she went from being considered for a five-organ transplant as she lay in the ICU, deathly ill, to being managed by aspirin alone. This happened because it was her underlying bone marrow overlap syndrome (MPN/MDS) causing her to have high platelets, which, in turn caused blood to form clots in large and small vessels. Aspirin reduces the clumping action of platelets, preventing clot formation. The life of a beautiful thirty-nine-year-old mother of four was saved because the right drug was matched to the right patient.

KENDRA’S CASE SUGGESTS a great plan: find a mutation by sequencing the DNA in the patient’s cancer cells, match a drug with activity against the mutated protein, and administer it irrespective of which organ bears the tumor. This approach combines the best of available technology and preselection of patients likely to respond, resulting in therapy tailor-made to suit the need of an individual patient. Precision medicine. Customized health care. Targeted therapy. Predictive modeling. Optimized strategy.

All sound terrific. The wave of the future. The fashionable thing to do. Mostly, it does not work. Here is what happened. Two types of trials were conceived. In one, called umbrella trials, tumors affecting the same organ but presenting with different genetic mutations could be matched with targeted therapies. For example, one lung cancer has an EGFR mutation—and the best treatment for that patient would be an EGFR inhibitor like erlotinib—while another patient’s lung cancer has a mutation in the HER2 gene, for whom Herceptin would be the right match. A second type of trials, called basket trials, pursues the same mutation as it appears in tumors in various organs; the idea is that the targeted therapy should work for all. For example, a mutation in the EGFR gene in a patient with pancreatic cancer should respond to erlotinib as well as a lung cancer patient with the same mutation. Many cancer programs have stepped forward to promote the idea of precision medicine because it seems the right thing to do.

There are several problems with the approach. First, it is extremely rare to have one gene driving one cancer. Second, even if such a mutation is identified, there aren’t many effective, approved, targeted therapies with which to treat the patient. Third, when a genetic mutation is matched to a drug, response is not guaranteed; in fact, the response rate is 30 percent at best. And finally, if everything works as planned and the patient even responds to the targeted therapy, the response offers no more than six months of improvement in survival over unmatched therapies. And this is the fundamental problem with most of the approaches; cancer treatments either don’t improve survival or the improvement is measurable in weeks or a few months, at tremendous physical, financial, and emotional burden.

How many thousands of tumors will need to be sequenced to find these rare patients, at what immense cost, and for what little benefit? Vinay Prasad argued in Nature in 2016 that the numbers will be very high; a sequencing program at MD Anderson Cancer Center was able to match only 6.4 percent of 2,600 patients with a targeted drug for identified mutations. A National Cancer Institute trial of 795 people who have relapsed solid tumors and lymphoma was only able (as of May 2016) to pair 2 percent of patients with a targeted therapy. Even then, Prasad reminds us, “being assigned such a therapy is not proof of benefit.” Only a third of patients respond to drugs given based on biological markers, and median progression-free survival is less than six months. Prasad estimated that precision oncology would benefit only 1.5 percent of patients, such as those in the NCI trial.

At the 2018 meeting of the American Association of Cancer Research, David Hyman from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center presented data on tumors in more than 25,000 patients. Of them, 15 percent matched with an FDA-approved drug and 10 percent with a drug in clinical trials. Prasad found similar proportions in his latest analysis, where 15 percent of 610,000 US patients with metastatic cancer were eligible for an FDA-approved, genome-guided drug. But once matched, just 6.6 percent likely benefited. Similar finds emerge from a study in Europe. From 2009 to 2013, the European Medicines Agency approved the use of forty-eight cancer drugs for sixty-eight indications. Only for twenty-six, or 38 percent, of those indications was there an improvement in survival, with a median benefit of only 2.7 months.

When I have questioned the practical feasibility of conducting such trials at the cost of hundreds of millions of dollars, one answer I regularly receive is a rather self-righteous one: “Well, Azra, for those 6.6 percent of patients, the extra five to six months or more mattered.” Of course the time mattered, although—since we’re talking about medians—it’s important to remember that half the patients would get less than the median benefit. And what about all the toxicity caused to the 93.4 percent who derived zero benefit from it? And all the wasted resources of sequencing thousands of tumors?

Take the example of the latest arrival in this area of precision oncology. In November 2018, the FDA approved the drug larotrectinib for the treatment of adult and pediatric solid tumors that express a neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase fusion gene (TRK). The trial of this small molecule, which led to approval of the drug, included a total of 55 patients, 22 percent showing complete and 53 percent a partial response. How long did the response last? Six months for two-thirds of the patients and a year for 40 percent. The test alone costs thousands of dollars per patient to find a very rare case. Treatment is likely to run in hundreds of thousands of dollars. For some two dozen patients who benefited for at least a year with this treatment, the approval of the drug is fantastic news. But bear in mind how small that number is in the face of the 1,735,350 new cases of cancer that will be diagnosed in the United States and the 609,640 who will die from the disease. This cannot be the most cost-effective way for us to move forward, yet such approvals are greeted as the new horizon, the game changer, the paradigm shift. It is my contention that these rare cases would be identified anyway through routine genetic profiling if we shift our focus to employing the genomic technology toward early detection. Instead of declaring victory, this approval by the FDA should serve as the impetus to envision better strategies for the future that can help a majority of cases.

Precision oncology ultimately fails because it ignores the evolutionary nature of cancer. As Theodosius Dobzhansky observed, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” In 1837, Charles Darwin sketched a tree trunk in his notebook with radiating branches representing the evolution of species from a common ancestor. Today, a graphic representation of cancer with all its genetic diversity and presence of multiple competing subpopulations of cancer cells emanating from the primary tumor is superimposable on Darwin’s tree of evolution. It has taken oncologists a long time to reach this understanding, thanks to a strange cleavage appearing among researchers early on. As molecular biology took off in earnest in the 1970s, investigators became convinced they would crack the cancer enigma. Reductionists, devoted to studying molecular genetic happenings in the cell, awash in overconfidence, drowned out the pluralists tracking the behavior of tumors as a whole. There was almost no cross talk between the two groups.

It is therefore no surprise that Peter Nowell’s clairvoyance about cancer being an evolving entity, with all its attendant therapeutic implications, an idea hailed as truly revolutionary today, remained largely ignored when first published in 1976. Fortunately, my husband, Harvey, was an exception. He immediately saw the genius behind Nowell’s paradigm, and he asked me to present the paper. Harvey was merciless in shredding one to pieces for the tiniest error during these weekly lab meetings. It was one’s familiarity with details that impressed him; any misstep, no matter how small, would discredit the entire presentation. I had to study the paper very carefully and read up on all sorts of background material in order to present the ideas coherently. That single paper helped me develop a radically different view of cancer very early on in my career. At the risk of testing the patience of readers not initiated into the specialized, dense, telegraphic language of science, it is worthwhile reproducing Nowell’s 138-word abstract from the classic paper “The Clonal Evolution of Tumor Cell Populations”:

It is proposed that most neoplasms arise from a single cell of origin, and tumor progression results from acquired genetic variability within the original clone allowing sequential selection of more aggressive sublines. Tumor cell populations are apparently more genetically unstable than normal cells, perhaps from activation of specific gene loci in the neoplasm, continued presence of carcinogen, or even nutritional deficiencies within the tumor. The acquired genetic instability and associated selection process, most readily recognized cytogenetically, results in advanced human malignancies being highly individual karyotypically and biologically. Hence, each patient’s cancer may require individual specific therapy, and even this may be thwarted by emergence of a genetically variant subline resistant to the treatment. More research should be directed toward understanding and controlling the evolutionary process in tumors before it reaches the late stage usually seen in clinical cancer.

That was more than forty years ago. Today, mapping mutational profiles in hundreds of individual tumors, combined with an astounding failure to develop any meaningful therapies for cancer in the interim, have confirmed the veracity of every word Nowell wrote. Simply stated, tumors also evolve by the Darwinian process of natural selection. Cancer begins in a single cell with one or more genetic mutations driving its release from growth-controlling signals. As the cell starts unchecked proliferation, its daughters pick up additional mutations, giving rise to multiple branches emanating from the tree. Each branch of cells carrying the driver mutation of the founder cell and the novel passenger mutations acquires novel metabolic and physiologic properties. Cells whose genotype matches the microenvironment develop a growth advantage, selectively expanding their population. Others wait their turn silently. No patient has one cancer.

There are countless cancers within each cancer. Since chemotherapy cannot kill every cancer cell, the surviving cells are selected to adapt and regrow. This is the reason why even the most successful targeted therapies fail; they only kill off the cells with peculiar characteristics susceptible to the treatment, selecting the outgrowth of others with biologic diversity.

Every cancer is unique, yet some common principles apply to all. First, the malignant process begins in a single cell for practically all known cancers. Mutations accumulate in key genes related to proliferation, cell growth, and cell death, eventually giving rise to a cell with a growth advantage. This cell divides rapidly to produce clones of itself. All the daughters will share the same foundational genetic mutations, but in addition, some of the daughters will sustain additional mutations that give them biologic characteristics that are distinct from the parent. Formation of such subclones happens constantly in a tumor, but usually, a few clones dominate at any given time while others remain on the sidelines, waiting for sequential recruitment. Of course, malignant cells also leave their natural habitats and wander off to form metastases.

The presence of innumerable, biologically distinct daughter cells with additional mutations, chromosomal changes, and altered nutritional and metabolic requirements is the reason why even the best of targeted therapies are of transient benefit. Treatment to which one clone is sensitive leads to the selection of refractory, resistant subclones and a more invasive disease. A biologically new cancer results with an entirely different natural history, novel rules of proliferation and differentiation, newfound invasive potential, unpredictable responsiveness to therapies. These frightening, abrupt transformations of the disease are a spectacle to watch through the clinical prism of changing blood counts, paraneoplastic syndromes, and immune reactions. As clinicians, we regularly witness this kaleidoscopic, repetitive dance of motley populations within populations of cancer cells unfolding in real time in vivo.

Competing groups of cells take turns expanding and shrinking; changing places, honeycombing, crumbling, only to be reignited into action by newly acquired copying errors in the reeling, replicating DNA strands, seeking comfort in uninhabited beds, forging alliances with cooperative bedfellows in marrow niches and safe havens of supportive organs. Occasionally, a leukemia arises in the background of MDS with such malignant ferocity that all we can do is watch the vertiginous descent into entropy, spellbound, helpless in front of so anarchic a rebellion.

The microenvironment of tumors plays a critical role in clonal selection and promotion. Properties of the soil vary in different areas of the body. When studying ovarian cancer, a tumor spreading by direct physical invasion in the abdominal cavity rather than traveling through blood or lymphatics, researchers found that subsets of cancer cells thrived in a site-specific manner. Characteristics of the microenvironment were differentially suited to promote the growth of one clone over another. One seed, one soil; change the properties of a seed through a mutation and it would have to find a new home. It is an important reason why preclinical cancer platforms employing cell lines and patient-derived xenografts are likely to remain wholly inadequate as models for drug development; they are devoid of the in vivo microenvironment.

There is no sickness worse for me than words that to be kind must lie.

—AESCHYLUS

The secret to success in life is relationships. The secret of relationships is trust. The secret of trust is acknowledgment of pure and simple truth. The problem in oncology, as in life, is that truth is rarely pure and never simple.

One historic incident that has stayed with me since I first read about it as a teenager growing up in Karachi involves Mr. M. A. Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. He spoke to a crowd of approximately ten thousand at a public gathering in Agra, India, in the early 1940s, years before the partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan. Probably five hundred people in that crowd had a passing knowledge of English, and about fifty of the elite among them understood it well. Trained as a barrister at Lincoln’s Inn in London, Mr. Jinnah spoke in chaste English with a British accent for forty minutes, and only in the last few did he address the commoners through a broken hybrid version of Urdu-Hindi-English. Shockingly enough, the crowd sat mesmerized throughout despite a complete lack of understanding. When asked afterward about what captivated them to such a degree, one man’s answer was, “Look, it’s true that I did not understand a word of what Mr. Jinnah said in English, but I have full trust that whatever he said was for my good and meant to protect me.”

Was the man’s blind trust justified? Trust is not just the sugarcoating glaze; it is indispensable, essential, vital. Too much willingness to trust is naive—a leap of faith that can earn deception. Yet a deeply meaningful blind trust is justified as long as the trustworthiness of the individual is already established. The man’s trust was based on an intelligent and experiential assessment of Mr. Jinnah’s previous actions, competence, reliability, integrity, and his demonstration of benevolence and empathy for the common man. Trust is not a static entity; it must be continually won.

Patients have the right to trust their physicians the same way Mr. Jinnah was trusted by his constituency. Do we deserve the trust?

In 1986, I had gone to Pakistan for a brief visit. One of the elderly female relatives at a family gathering, delighted to see me after several years, asked a curious question. “I don’t care how many degrees a doctor has, even if they are known to cure cancer, if they don’t have the reputation of shifa in their hands, I stay miles away from them. What I want to know is if you have been graced with shifa in your hands yet?” Shifa is an Urdu word loosely translated as “the healing power.” It is the equivalent of blind trust in one’s doctor—a powerful, intangible confidence that no matter how deadly their health challenges, and especially when medical knowledge is stumped, the physician alone possesses the wisdom to remain sensitive, to proceed in caring, empathic ways, always exclusively focused on the patient’s interest.

Lady N. thought I possessed shifa. She expressed her confidence at least half a dozen times during every clinic visit. She trusted me with her life. I obsessively tally the number of ways in which I let her down, this terrified, trusting, vulnerable woman, sitting in the consultation room, her mind and body besieged from within and without, desperately seeking a lifeline I had no power to conjure. Lady N. and I both knew that she had a fatal illness, that it was simply a matter of time before she would enter the bedlam surrounding end-of-life issues. Obviously, I had no cure to offer, no magic bullet to eliminate the coming leukemia, and each time she expressed her implicit trust in my power of shifa, I reminded her gently of what was expected. She scoffed, she laughed it off, she changed the topic, sometimes she became agitated, abruptly walked out. I broached the subject of involving our palliative care team, which she dismissed out of hand. What about a psychiatrist? “I have been on antidepressants practically all my life. My mother thought I was hyper when I was two! I don’t need more doping, thank you.” Lady N. simply refused to accept that the end could come for her. She demanded therapy for her cancer, not her mind, willing to be a guinea pig for any experimental approach I could concoct.

Things spiraled out of control in her case with frightening speed. Within days, she was admitted to the hospital with a high fever. I sat on her bed early one morning as she struggled to breathe. We were, for once, without the usual team of nurses, oncology fellows, and medical students crowding the bed, craning their necks to catch snippets of our conversation. Strangely enough, the intimacy of solitude had a distancing effect, introducing a formality in our communication, an uncharacteristic courtesy with which to speak about unspeakable things.

“We have to intubate you now and place you on a respirator. You can refuse.”

She caught her breath as the color drained from her face, then rallied and shot back, “Refuse and do what? Dr. Raza, I will not give up. Do whatever you can to keep me alive. For God’s sake, my mother is alive at a hundred. I have good genes. Freeze my body if I die. I want you to clone me when you have the techniques worked out. I know you can. You are the only one I have full confidence in.”

I kissed her and called the anesthesiology team. We wheeled her down to the MICU. Within minutes, she was intubated, placed on a respirator.

What followed was less about supporting life and more about prolonging death. There was zero chance that Lady N. would ever be able to breathe on her own again since her fundamental issue was not the rapidly progressive pneumonia but her untreatable, fatal cancer. Infections were flaring up precisely because all of a sudden, pathogens had a free pass in her leukemia-riddled body. The immune system was fast approaching a state of total collapse as the bone marrow failed to produce the most critical first line of defense, white blood cells. I knew precisely what frightful days lay ahead. She did not.

I am a clinician first, and my medical, moral, and ethical obligation is to relieve distress and suffering caused by disease. I should enable my patients to benefit from the best that science and technology has to offer, not be hurt by it. Yet by offering to intubate her and connect her to artificial life support, as if death were an option, did I fail to protect Lady N.? What forces compelled me to offer her a choice of intubation, inviting her to accept unspeakable horrors that she had no clue about? The law, of course. What had I done to help Lady N. accept mortality? Did I do enough to explain the hopeless nature of her leukemia, the pointlessness of placing her on artificial life-support systems? Was it a failure on my part as her treating oncologist that somehow I transmitted a false sense of hope to Lady N.? Did I use language that made sense to Lady N. instead of confusing her? Or was it Lady N. whose nature dictated revolt, who would never take things lying down, no matter how much I tried to explain the hopelessness of her prognosis? What I know beyond a shadow of doubt is that to intubate her and attach her to a ventilator was the worst possible thing to do to her, and yet, against my better judgment, I was forced to give her the choice. So was I morally wrong in knowingly letting her enter the hellish nightmare of the next week? Where does medical and individual responsibility end and societal responsibility take over?

Was Lady N. wrong to trust me? Where is my shifa?

TODAY, ANY TALK of death is considered morbid and unhealthy, but in the mind-set a century ago—when war, disease, and famine raged unchecked—it was an ever-present threat. Life expectancy was in midforties at best. Rather than being a sad ending, often death was treated as a new beginning. Emily Dickinson, imagining the scene of her final moments from beyond the grave, an unfathomable point of eternity, paints death arriving with the gallantry of a dignified escort:

Because I could not stop for Death—

He kindly stopped for me—

The Carriage held but just Ourselves—

And Immortality.

We slowly drove—He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility—

Not so, our Lady N. Drama queen that she was, she was not fading quietly into the twilight anytime soon, and no one was going to drive her carriage gently into the sunset.

Over the next week, an unrelenting chaos descended upon her unconscious body. She suffered every ignominy that a mechanical life-support system could possibly visit upon its subjects. Her body expanded grotesquely, unevenly, to accommodate six extra liters of fluid pumped in to combat hypotension, the fluid stagnating in strange crevices of her body because her failing kidneys were unable to expel most of it. Her eyes, circled by blue-black rings due to periorbital edema and bleeding, bulged from a shiny, swollen, unrecognizable, raccoon-like face. Her entire skin, forced to lodge pound upon pound of relentlessly multiplying, roving, vagrant leukemia cells, became studded with a smattering of rock-hard little mounds, referred to as chloromas because of their sickly green color, sprouting amid flowery patches of tiny red-and-purple petechial spots announcing shattered capillaries and profoundly low platelets. She had tubes coming out of every orifice, lines placed in multiple large veins from the jugular to the femoral. Monitors recorded everything from oxygen saturation and vital signs to the pulmonary arterial pressure and cardiac rhythm; colorful screens blinked from adjustable metal poles on wheels, beeping insistently, alarming visitors, alerting nurses, ignored, switched off, only to restart screeching in unison moments later.

Mortality steadily eroded the searing desire for eternity, piling a thousand humiliations at once on her decaying, battered, abused, assaulted, gigantic frame, shackled to the gadget-rich MICU bed with a hundred tubes and pipes. Lady N., suspended in a bizarre state between life and death, fought the funeral in her brain. Every groove, ridge, and fold in her cerebrum revolted. Every hair follicle on her skin, every cell in her organs, put up a fight. She refused to die. She pushed back, drawing upon astonishing psychological and physical reserves, producing a multifaceted tour de force of rebellion that challenged the limits of medical imagination and decorum. She managed to subvert the crippling blows of her fatal disease into an epistemology of endurance by her unyielding, uncanny, scandalously defiant posture of refusal.

Her 101-year-old mother finally stepped in. A devoted aide wheeled her into the MICU. Accompanied by friends of Lady N. and by her lawyer, she formally petitioned for her daughter to be taken off life support. An abrupt, eerie, unnerving silence replaced the racket of beeping and pinging alarms as machines switched off, IV lines were pulled, tubes yanked, monitors unplugged.

KEY OPINION LEADERS providing therapeutic algorithms rely on studies demonstrating success or failure of a strategy in the populations as a whole, but management of patients and the questions of existential challenges posed by each unique individual remain the responsibility of the treating oncologist. No degree of technologic improvement, national debates on “right to life” issues, or guidelines from evidence-based medicine can help in these deeply personal, intimate moments. Repetitive transmission of clinical trial results or regurgitation of statistical probabilities about chances of response and survival do not necessarily help patients. Devoid of emotions, recitation of facts is like a jockey without a horse. This moment calls for a serious reckoning. Patients disoriented and confused by the caprice of their rapidly evolving cancer and the absurdities of medical choices need more than medical advice from their oncologists. For their part, physicians must now harness all their own emotional, psychic, social, intellectual, philosophical, and even literary resources to engage with the patient and their families in repetitive, substantive conversations informed by empathy, kindness, and understanding. A more balanced, candid conversation about end-of-life issues, a frank explanation regarding the limits of medical and scientific knowledge should supplement the discussions of treatment options from the first meeting and continue as often as possible through subsequent encounters. Nowhere is the science of medicine replaced by the art of caring as in the final days of a terminal illness. Yet that is precisely where oncologists turn over the care of patients they have looked after for years to a new hospice team.

In addition to the end-of-life and do-not-resuscitate conversations, an equally important question is, why could I not offer Lady N. anything better than 7+3? Most large clinical trials conducted by cooperative groups of oncologists across the country in the past decades have concentrated on tweaking the doses, schedules, or formulation of the two drugs with minor improvements in the response rates. Harvey and I became so allergic to 7+3 discussions in every national meeting we attended that, following the formula of the great Paul Farmer, we also started using it to refer to individuals who use seven words when three would suffice. In the midst of a perfectly serious scientific session, or during a dinner conversation with guests, if anyone appeared to drone on tediously, Harvey would lean over and whisper, “Seven and three.”

The latest entry into this arena, hailed as a paradigm shift by many reviewers and editorial contributors, is the lipid-encapsulated combined version of 7+3. In a large phase 3 clinical trial conducted at the cost of tens of millions of dollars, this new 7+3 version improved survival by 9.6 months compared to 5.9 months for the standard 7+3. Why is our bar for improving survival so low? Is 3.7 months the best we can offer our patients at almost ten times the cost of the previous regimen?

An improvement in the last fifty years in AML treatment has been that by using multiple parameters—including clinical presentation and biologic and genetic characteristics of leukemia cells—we can identify individuals likely to benefit from chemotherapy alone or those who are at high risk of relapse. Studies have shown that for the elderly (defined as anyone over sixty) or those with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (that is, AML arising from MDS or after exposure to toxins like chemotherapy), even if a complete remission is produced in response to 7+3, the overall survival is not improved. The leukemia such as Lady N.’s that arises in the background of a myelodysplastic syndrome is notoriously resistant. In her case, 7+3 could be used to reduce the burden of leukemia in the bone marrow but would have to be followed by a stem cell transplant if the aim was to improve survival. Given her age and other comorbid conditions, a transplant was out of the question (it would kill her faster than anything else). Then what would be the point of torturing her in the hospital for weeks, treating her with agents that carry potentially lethal side effects? Why not simply provide the best supportive care available, with transfusions of platelets and blood, and treat infections as needed? Why not let them pass their last days at home with loved ones? Actually, oncologists do offer the choice of aggressive cytotoxic therapy versus supportive care with transfusions and antibiotics as needed. This is where we enter the strange circle where denial of the outcome of terminal illness, extreme fear of death, and the inextinguishable flame of hope merge together to cloud judgments. Almost all patients refuse supportive care and choose the aggressive approach. As did Lady N.

LADY N. PASSED away due to complications related to her MDS. Yet in a larger sense, MDS could not, and did not, defeat her. She defeated MDS by inspiring countless others she met because of her MDS. She dared to play Russian roulette with a loaded gun. She was the loaded gun possessing the power to die but without the agency to pull the trigger:

My Life had stood—a Loaded Gun—

In Corners—till a Day

The Owner passed—identified—

And carried Me away—

—EMILY DICKINSON

I miss her greatly. At the oddest of moments—like when I see a cat, or an especially funny cartoon, or a scared young medical student, and most of all, because of a comment, a gesture, an expression, or a question from an MDS patient—her laughing face accosts me. I smile. I silently mouth the words…

Lady N., Zindabad! (Live long!)