Here’s how Remote says Friday got its name:

When the rain of Thirstday finally stopped, the world had gone mud messy, and Remote couldn’t do anything without getting dirty.

“This is the worst,” Remote said. I picked up my foot and looked at the clumps that clung to it. “It’s almost as bad as being thirsty.”

Current problems are always worse than the problems you’ve solved. Remote sat in the muck and stared off at the puddles and grime. Remote couldn’t get motivated. Remote’s life seemed like a disaster.

But just then, a woman I had never met waltzed into my village. She had a unibrow, and she was dressed in vivid colors, and she had an angry posture, and her hands were artist’s hands. “Is it true,” the woman said, “that you have the power to name days?”

Remote thought. Was it a power I had? Was it anything?

“Maybe,” said I. “Depends who’s asking.”

The woman raised her chin. “I am Frida,” she said, “and I can fix your troubles.”

“How?” Remote asked. I grabbed a fistful of mud, and squeezed it so that it dripped through my fingers. “This stuff is everywhere.”

“Correct,” said Frida, “but you can solve sadness with work.”

“Sadness?” said Remote, holding open my dirty palm. “That’s what you’d call this?”

“That I’d call mud,” said Frida. “But the way it makes you feel. How you’re staring off at nothing and feeling sorry for yourself. That I’d call sadness. But all you have to do with sadness is remember that everything passes. To know that all things can yield other things.” Frida waved her hand over the earth, and a hibiscus sprang from the spot she had gestured to, and great hibiscus flowers as wide as dinner plates bloomed. They were the most brilliant pink imaginable.

“No mud,” said Frida. “No flowers. You have to focus on how the pain of now can lead to the joy of tomorrow.”

“So you’ll turn all this mud into flowers?”

“Of course not,” said Frida.

Remote became sadder.

“We’ll turn the mud into flowers together.” Frida stroked her unibrow. “I have seeds for us all.”

Frida passed out pouches to Remote and the Earthlings and we waddled through the mud scattering seeds.

In time, flowers grew. Once the flowers came, the earth was dry again. To commemorate our hero, we named the day Friday.

And Friday became the day to celebrate the end of the sadness. To listen to music. To go out. To enjoy the evening.

I lay in bed looking at the scabs on my knuckles and every now and then I counted the money I’d found in my uncle’s wallet. Money is so weird. In jail, people hide it up their asses. They call that a prison wallet. If a kid loses a tooth, you put a bill beneath their pillow. That bill could’ve been up someone’s butt a week before, could’ve passed through the hands of meth dealers who’d murdered people. And then that kid takes it to buy candy.

I don’t know.

I was going to be washing dishes that night at Broth, and I didn’t want to do much. I wanted all my energy to be saved. I knew once I got out of bed, I’d pace around. My nerves would start to work. I’d burn myself out from the inside.

What would I tell Peggy? What would she do after she knew? What would they do to me? Where would I go then?

I tried to sleep the day away, but I just lay there looking at the texture of the ceiling. I texted Erika that I missed her, but she didn’t text back. I texted the unknown number that Bennet had texted from, but it didn’t text back. It’s weird waiting for that kind of communication. Because you don’t know what’s been seen and ignored, and you don’t know what hasn’t been seen yet.

You start to make things up. You start to imagine the worst. Maybe Erika didn’t miss me back. Maybe the person who had the unknown phone was just laughing at me.

I picked up my philosophy book and read about another philosopher. I read about Epicurus. He was a hedonist. He wanted to know why people were happy or unhappy. Everyone thought that he was kind of a wild dude. That he banged virgins and drank all day. Ate whatever. Did nothing but dance. But that’s not the way he was. He studied happiness, but he was real chill about it. He ate almost nothing. Just enough to keep himself alive. He only owned a few pairs of clothes. He said people make three big mistakes when they think of happiness. He said people think happiness is this:

- Sex

- Money

- Luxury

Which is kind of like that song of Drake’s called “Successful.” He wants money, cars, clothes and hoes. Epicurus said, though, that those things don’t mean shit. Epicurus would’ve looked at Drake and called him a miserable motherfucker. And if you think about it, maybe it’s true. Go watch Drake giving Rihanna the Vanguard Award. It might be the saddest shit on the internet.

Instead, Epicurus said that what you really want is:

- Friends

- A job you enjoy

- Time to think

Can you imagine if Drake sang:

I want some people

People who I like

A job that’s alright

And time

To unwind

I just wanna be successful

Dude wouldn’t sell shit. He’d be back in the Six, and maybe he’d be the happiest motherfucker alive.

When I got up to shower, Peggy was gone. I knew rent was due, so I put the eight hundred dollars on the kitchen table, texted her that I’d left money, and then headed to work.

On the way, I saw Autistic Ross, and I went up to him to see if he had any answers.

“You boy,” he said to me. “We talked afore. The other day. About right here.” He looked around on his little spot. He had on a pink Polo shirt and he was wearing navy slacks. He pulled his elbows up at his sides and he smiled big and squirreled around some. “Talked Alaska,” he told me. “Talked the dadgum weather,” he said. His top teeth dangled out of his grin.

“That’s right,” I told him. His joy was infectious. His words seemed to cleanse me. “I had a question for you?”

“For me? You gonna ask if I’m cold? I’m about to go get my jacket on,” he said. “Beyond that I am generally lacking when it comes to the answers department. Momma use to say I’d forget my name if it was any longer than Ross. But I like Ross better than any other name anyhow, but I couldn’t tell you why. Ain’t that funny how you never really know why you like what you like. Like I like creamy peanut butter better than crunchy peanut butter, but if you chew on crunchy peanut butter a bit, it gets real creamy in your mouth. Maybe I just don’t like all that dadgum work.”

Everything he said made sense, but I swear you got stupider just following his lines of thought. “When I came by the other day you showed me something?”

“I showed you where the body’s buried?” He had a shocked look on his face.

“What?” I said.

He cackled. “That’s my little joke. I tell it different ways. Sometimes people say, ‘Wanna know a secret?’ and I say, ‘I know where the body’s buried.’” His eyes watered. “The way I just told it to you. I ain’t never told it quite that way before. Maybe you can teach an old dog new tricks.”

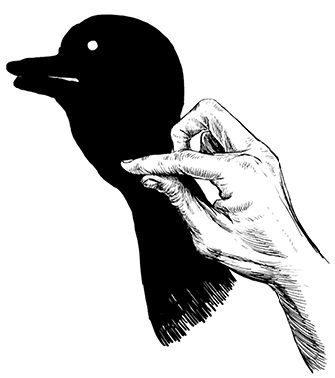

“Maybe,” I told him. I could feel my brain shrinking. I held up Remote.

“I know that fella.” He held up his hand like mine.

“Yeah,” I told him. “Where’d you learn that.”

“Promised not to tell,” he said. “And Ross don’t break no promises. I break wind sometimes though.” He kinda leaned to one side and clenched his face. “It was a quiet one,” he said. “Oh, boy, it’s smelly though.”

“What the fuck?” The stench was insane. “What do you eat?”

“Sausage,” he told me. “Peanut butter. Raisins.”

“Fucking rank,” I said and I started to walk off.

“Come again,” he told me, and I swear the smell followed me a half a mile.

At Broth, the banging around had started, and I jumped into my apron and filled up my sinks. There wasn’t much to wash, but there was a lot of stuff to run back. There were stacks of plates, pans to shelve. There were forks and spoons and knives to wipe clean. They had to be spotless.

Chef showed me a spoon and was like, “Would you put that in your mouth?’

I looked at it. “Sure.”

She held it closer to me. There were spots on it, I guess. “Sure, Chef. But that’s old dishwater,” she said. “That’s about as bad as dried sweat. Would you lick my armpits?”

“Are they shaved?”

Chef laughed. “You’re a fucking gem,” she said. “Spotless spoons,” she told me. “Spotless forks. Spotless knives. Spotless everything.”

“Spotless armpits,” I told her.

“Spotless armpits, Chef.”

It’s weird when you look at a tub of forks and realize that every single one of those is going to go into a different person’s mouth. At home, those forks and spoons you have go into five people in an average cycle. The forks and spoons at a restaurant go into dozens of people in a night.

I thought about that as I was getting rid of all the spots. That everything I was cleaning was going to be inside somebody soon.

The waiter who had given me the ride came up as I was polishing the silverware. “Moving spots?” he said.

“Huh?”

“Matter can’t be created or destroyed.”

“Okay.”

“You think you’re getting rid of the spots, but you aren’t. You’re moving them.” He pointed to the silverware. “From there,” he pointed to the towel I was holding, “to there.”

“Chef,” I hollered. “Washing dishes blows my mind.”

“Oh, it blows,” she called back.

That afternoon, a storm came through and we caught four inches of accumulation, and we only had three tables all night. Almost everything I had thought before was a lie. My silverware barely went into anybody.

“Can’t trust this Indiana weather,” Chef said.

She saw my knuckle. The warm water from the sinks had made it open back up. “What happened?”

“I caught it on something.”

“Health inspector sees that and we’d get cited for sure. Let’s wrap it up.”

She took me into the office and pulled a first aid kit down from a bookshelf full of cookbooks. “You read at all?” she asked, I guess having seen me eye the shelves.

“Yeah,” I told her. “I’m reading about Epicurus.”

“The food site?”

“Nah, the philosopher.”

“This is gonna sting.” She had an alcohol pad that she rubbed over my wound, and it felt hot and cold at the same time and my eyes clenched. “Would you read a food book if I gave it to you?”

“Sure,” I said. I gritted my teeth. “Eventually.”

“This lady’s my hero.” She reached up and grabbed a book called Blood, Bones & Butter. I took it in my good hand, and Chef took back my right hand and put a butterfly bandage over the split knuckle and smoothed it over. My mom was the last person who’d held my hand. I’d hooked up with some girls, but I hadn’t held hands with anyone, and definitely not like this. Chef held my hand like she felt sorry for it. Like it meant something to her to help me, and it occurred to me that I was going to read the book she gave me and that the woman who wrote it would be one of my heroes too. Then Chef handed me a latex glove. “Hand condom,” she told me. “No knuckle AIDS for you.”

I put it on. “Thanks, Chef,” I told her.

“De nada,” she said. “Now get to fucking work.”

A slow shift in a restaurant and a busy shift in a restaurant might as well be two different jobs. I had hoped my night at Broth would take away my time to think, would fold me into its insanity and the hours would go streaking by. Instead, we all waited tensely in the kitchen for customers who never came. Listening to the energy of the kitchen purr.

“Fucking lame,” hollered Chef.

She started cutting the servers. She had the cooks kick me all the dishes they didn’t need. The kitchen was dismantled into a skeleton configuration. The chattering of it sounded like machinery. All the hotel pans consolidated, all the elements of the line shifted down to one station. Chef had me take everything out of the walk-in cooler. She had me wipe down the surfaces. She had me put everything back.

“Imma spell a word,” Chef told me, “and you tell me what it spells.”

“Okay.”

“C-H-E-V-R-E.”

I thought a second. “Cheaver,” I said.

Chef smiled. “Shev-ra,” she told me. “It’s a cheese. Ever had it?”

“Nah.”

She opened a container, took a plastic spoon from her pocket and spooned me a taste.

“You always have spoons in your pocket, Chef?”

“Always. I need to get away from plastic though. I need to find some wood ones or something. They’re great for tasting, but they say by 2050 there’ll be more trash in the ocean than fish. By weight,” she said. “But try it.”

“It looks like cream cheese,” I told her.

“It’s goat though.”

“It’s goat?”

“Well, goat’s milk cheese. So it doesn’t taste like cream cheese. And cream cheese isn’t really cheese anyhow. And we wouldn’t use it in my kitchen. Neufchâtel maybe.”

“Noof-sha-what?”

“We’ll get to it. Try the chèvre.”

I did. The little bite of it took over my mouth. The wallop of it was astounding. It was hideously creamy. It was disgustingly delicious. “It tastes like how river water smells.”

“Like it?”

I swallowed. “Afterwards tastes like change,” I told her.

“Change?”

“Money,” I said.

“Metallic,” she said. “It’s local. See? You learned something.”

I threw away my spoon.

When I was done cleaning the walk-in, I started scrubbing away at what all the cooks brought me.

My glove kept filling up with water, and it kept breaking, and after I’d changed it a few times, I decided it was a waste.

Eventually, my Band-Aid got lost in the dishwater, and if I bled on anything, I just sprayed the blood away.

There was one table left late in the evening, and the conspiracy-theory waiter kept coming in and rolling his eyes. “If they tip well,” he said, “I don’t mind. But I hate working this late for one table.”

“They’re drinking though, right?” said Chef.

“Like fish, Chef.”

“Then let ’em stay.”

The waiter went back out to the dining room and came back a bit later with a dessert order. “And,” he said handing the order to Chef, “they want to know if they can see the kitchen.”

I’d never even heard of that, but apparently it’s a thing. Especially in nicer restaurants. People want to get pictures of themselves with cooks, they want to see where their food came from.

“We’re pretty broken down,” said Chef. “But as long as you tell them, I don’t mind.”

I had filled a mop bucket the way I’d been shown on my first shift, and I was about to go over the kitchen floor. Normally, we would’ve scrubbed the floors with a long-handled brush first, but the night was so slow Chef said we didn’t need to.

“Hang back on mopping a bit,” she told me. She went into her office and grabbed a fresh jacket, took off her hat and messed her hair a bit. “I look okay?” she asked.

She did.

It occurred to me then, I liked women. I didn’t like girls. I liked Peggy and I liked Chef. I liked them physically, but there was something more than that. They had power over me, they had control. Peggy could have kicked me out onto the street and Chef could have fired me, and something about that was interesting. They could also teach me. They knew things I didn’t know. And I’m not sure that’s what men are supposed to like, but you can’t help what you’re into.

I mean, I knew plenty of girls who dated older boys. Hell, they almost all did. Part of that was because the older boys had cars, but maybe there was something else to it.

It used to be more common for men to date women a lot younger. I think these days it’s more frowned on. But maybe the men like younger women for the same reason I liked Chef. Just because. They liked girls who needed their money. They liked girls who they were smarter than. Who they had power over, and maybe those women liked that the men had power. Liked they had money. Liked they had knowledge.

It’s weird how society makes decisions for us. How society tells us how to feel about what we like—about what we’re like.

If I told my friends that I was into Chef, they would tease me. If I told my friends that I had a girlfriend two years younger than me, they’d think it was cool. But where do all the lines start and stop, and why do we have to carry the opinion of the world on our eyes like lenses?

I suppose you have to have some boundaries. You have to tell men they can’t fall in love with seven-year-olds. You have to tell women high school teachers they can’t sleep with their students. You have to tell bosses they can’t fire employees for refusing them blow jobs. I don’t know. It’s confusing. All of it.

I barely recognized her when she came to the back because her mouth was blue from drinking wine and her eyes looked wonky, but she recognized me right away.

“I know you,” the kitchen visitor told me, wagging her finger. She was wearing heels and she kinda stumbled a bit, but the conspiracy-theory waiter steadied her, and then she reached down and took off a heel. It was my counselor. The one who had pinned the vape on me.

“It’s not the safest place to go barefoot,” Chef told her.

“Where’s the chef?” my counselor said.

You could feel a kind of temperature change, and Chef said, “Gone for the evening.”

And the counselor looked at the waiter and said, “But you said . . .”

“Just stepped out,” I said. “Just like right now.” I pointed to the back door. “Had to go see . . .”

“A man about a man thing,” said Chef. “Y’know,” she said. “Men.”

My counselor nodded heavingly. “You can’t count on ’em,” she said. She pointed at me. “This one’s kinda trouble.”

“I hope so,” said Chef. “This is a kitchen. We only hire trouble.”

“Weed smoker,” said my counselor. “Vape pen.”

“Vaping’s not smoking,” Chef said.

“True,” said the counselor. “He had a funny word for it. What was that funny word?”

“Candy fog.”

“Sounds like a stripper,” Chef said.

“His mom didn’t think it was funny,” my counselor said. “I told her what you wanna be when you grow up.”

“You mean my aunt?” I asked the counselor.

“Some woman,” she said. “She said you’d be lucky to be that bicycle guy. That you’d be lucky to be homeless. She didn’t think you’d live long enough. I figured she was gonna kill you.”

“I’m still here,” I said.

My counselor looked around a bit. “Well I’ve seen it,” she said to the waiter. “Food was AH-MAZING.”

“Thanks,” said Chef.

Then the waiter helped her back to the dining room.

“No wonder kids shoot up schools,” Chef said once the counselor was gone.

At a certain point it gets so cold you can’t even tell you’re alive anymore. That night was like that—standing outside made you feel like you’d crumble to dust and drift off with the snow—but I didn’t want to ride with the conspiracy-theory waiter. My pants were wet, and my shirt was soaked, but I bundled into my jacket and threw up my hood, and I waded through the snowbanks wondering why people liked winter. And some people did. I knew that some folks watched the weather for blizzards and kind of had blizzard parties the way we’d have hurricane parties back on the Texas coast.

In 2015 my last guardian bought extra beer for Hurricane Bill and I was only fifteen but he let me drink with him. We didn’t get much more than rain. Too far south. But we sat on the back porch under the easement in candlelight slurping Lone Stars, and he told some ghost stories, but none of them stuck with me. It’s weird how some things you remember and some things you forget. And it’s weird how you don’t get to decide. You can’t trim away things from your brain that you wish weren’t there, and you can’t dig out the memories that seem lost forever. Your brain shows you what it wants you to see. Your mind is totally at its mercy.

The snow was stacked like white scabs and the streetlights hummed yellow in the hiss of new snow falling. Flakes the size of my thumbnail. They drifted down, and their silence seemed to slow the whole world.

I felt cold enough to die but I knew I wouldn’t. We’d read a story earlier that year in English about a man up in Alaska, I think. He had a dog, and he needed to start a fire but couldn’t. And he kept worrying that it was 50 degrees below. At a point, to keep his hands warm, he thought of slicing open the dog, of burying his hands in dog guts the way Han Solo kept Luke Skywalker warm inside a tauntaun on Hoth. But it wasn’t 50 degrees below, so dogs were safe near me and my hands.

Peggy had known about my being suspended. She knew about the Bicycling Confederate and Autistic Ross too and how I said I wanted to be like them. She knew about the vape pen. She knew about Remote.

But she said she didn’t.

And I guess in my shock of all that, and in the pain from my uncle, my mind started going funny places. I could see, somehow, in my mind a vast puzzle being pieced together. A weird conspiracy against me. My aunt somehow planning all these things. My uncle’s death. My seeing Remote on other people’s hands. And I didn’t know why, but I just knew she was deceiving me.

The apartment lights were on when I finally got home, and Peggy sat cross-legged on the sofa. She wasn’t doing anything. You could tell she was waiting for me, but she didn’t know what I knew, and because of that I had power over her, and she didn’t seem nearly as sexy as she sat in the warm light.

When I went inside, she shot up to her feet. “You leave that money on the table?” she asked.

“I did.”

“Where’d you get it?”

“Like you don’t know?”

“You think I’d ask if I did?”

I went to the refrigerator and opened it up. There were some beers that my uncle kept around, but he never would let me drink in the apartment. He didn’t want me to become like him. I grabbed a bottle and twisted off the cap.

“You know what your uncle thinks of that,” Peggy said, and she made to come and take the beer from me.

But I said, “I know what he thought about it.”

Peggy and I locked eyes.

“What do you mean?”

I took a swig of beer. The bottle kind of hooted when I pulled it from my mouth, and I wiped my lips with my busted knuckle, my tongue numbing in the alcohol wash. “It’s called past tense.”

“I know what it is. Where’s your uncle?”

“Why are you lying?” I asked. “How do you know about Remote?”

Her face clenched. “About what?”

I held my hand up and made Remote. I spoke, and as I did, I had Remote’s mouth move with mine. “You knew I was suspended.” I widened my eyes. “You knew about the bicyclist and Ross. I saw my counselor tonight, so there’s no use in lying. You somehow knew about Remote and you somehow got Ross and the Confederate to play along in your game. I’m not sure why you’d do that, but there can only be a few reasons.”

“What the fuck are you even saying?”

“Either you killed him and wanted to pin it on me, or you killed him and wanted me to find him so I’d run away.”

“I am literally under the impression that you’ve lost your mind or are on acid.” She looked at Remote. “What the fuck are you doing with your hand?”

“You’re a murderer,” Remote and I told her. “You’re a killer and you’ve been lying this whole time.” Remote was up near her face, so close she would smell his breath if he had any. “You’re twisted and evil, and you’ve been playing me this whole time.”

“What?”

“You talked to her on the phone.”

“Who?”

“My counselor.”

“When?”

“On Friday.”

“I was drunk as fuck on Friday.”

“Yeah, had to steady your nerves?” Remote and I said. “Couldn’t get over what you’d done? Killer. Murderer.”

Peggy slapped Remote and my hand went open. “Killer? Murderer? Are you crazy? Where’d you find the money? Think about it. Where?”

I didn’t have to think. “In Uncle Joe’s wallet.”

“In his fucking wallet,” she said. “You think I’d kill someone and not take their money?” She put her face near my face.

“Whatever,” I said, and I finished my beer in a few giant pulls. When it was empty, I set the bottle on the counter. “I don’t need to talk about it.” And I went to my room.