ONE

Do Not Exceed the Stated Dose

Madeleine was a country girl. You could hear it in her speech, especially when she was excited. She carefully examined the new arrivals and then suddenly drew back, her black eyes round with surprise, her hair on end.

‘Crumbs!’ cried Madeleine loudly. ‘Just look at thik girt hummock!’ And had there been others there to look, they would have seen five normal newborn pink babies, each the size of a little finger-nail, and a sixth that was newborn and pink but most definitely not normal, so huge and strong and active was it.

Already, at half an hour of age, it was beginning to crawl blindly about the nest, steamrollering its way over its brothers and sisters, and lifting its blunt snout hungrily in the air.

‘Crumbs!’ said Madeleine again. ‘He’s as big as a baby rat! Whatever will his father say?’

The father of the six was a mouse of a different colour. Not only had he a dark grey coat, in contrast to Madeleine’s warm brown, but he had come originally from a very different background. He had been born in fact behind the panelling of a room in an Oxford college, and had travelled down to Somerset as a youngster, quite by mistake, in a trunk full of clothes. The occupant of the room had been a Professor of Classics, and with such a history of culture behind him Madeleine’s husband considered himself several cuts above country mice. His name was Marcus Aurelius.

Marcus Aurelius had his own private den, close to the sitting-room fireplace. Later that day he rose from his bed of torn newspaper, where he had been reading snippets of the Western Daily Press. He made his way down the passage behind the sitting-room wainscot that led to the family home. This was in a hole in the wall at the back of the larder. It was the beginning of winter, and as usual they had come into the warmth of the cottage from their summer residence under the raised wooden floor of the pigsty at the bottom of the garden.

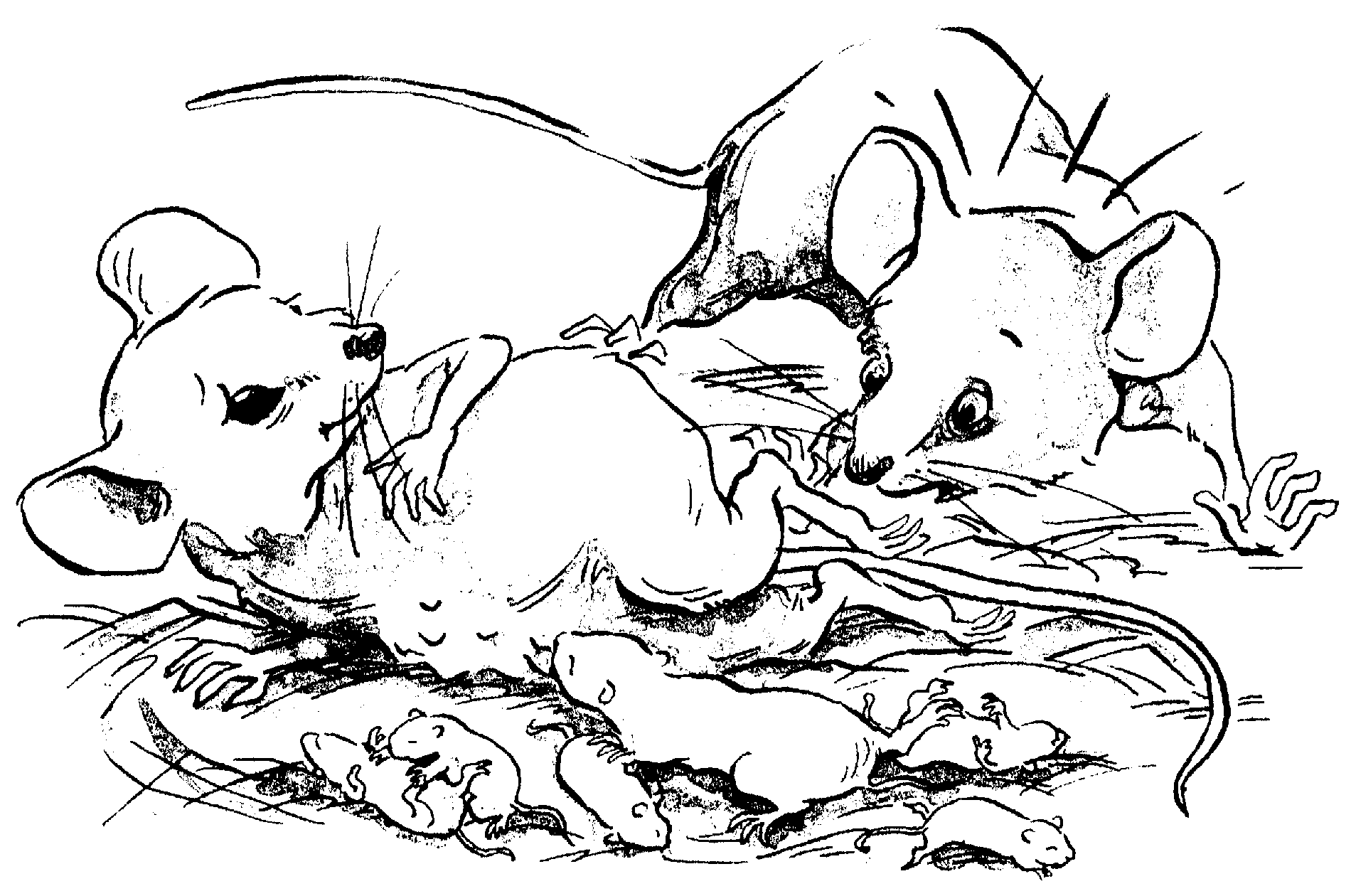

He found his wife, looking, it seemed to him, rather worried, sitting in the middle of her nest. Of babies he could see no sign.

‘Well, Maddie my dear,’ he said, peering shortsightedly, for reading in a bad light had weakened his eyes, ‘when are we to hear the patter of tiny feet?’

‘Oh, Markie, Markie!’ cried Madeleine in a distracted voice. ‘Tidden the patter of tiny feet we shall hear. Tis the thunder of hugeous girt big ’uns!’ And she rolled upon her side to show what lay beneath her.

Marcus Aurelius gave a squeak of amazement at the sight which met his myopic eyes. Five feeble babies, already more blue than pink, fumbled weakly in search of their mother’s milk; but in vain. Only too plainly it had all been drunk, by the red swollen sausage-shaped monster that lay distended in the centre of the nest. And even as the horrified father watched, the giant baby bestirred itself, bullocking its way through the others and knocking them flying as it made once more for the milk-bar.

At last Marcus Aurelius found his voice, after a fashion. Normally long-winded, the shock reduced him to a series of gasps.

‘Never in all my . . . what on earth . . . how?’ he gulped.

‘Oh, Markie,’ said Madeleine in low tones, as though fearful that the huge infant might overhear her. ‘I’ve never seen such a big ’un neither. And it ain’t a changeling, if that’s what you’re thinking, it’s mine all right, I should know. And as for “how”, I can’t rightly tell. Must be something I ate.’

She sounded so miserable that Marcus immediately set himself to comfort her.

‘Now, now, dear girl,’ he said briskly. ‘You must look upon the bright side. The, er, boy – it is a boy? Yes – is a magnificent specimen of mousehood, beyond any shadow of doubt. A great credit to you, Maddie my love, very great.’ He paused. ‘Very great indeed,’ he went on absently.

‘Yes, but what about t’others, poor little mites?’

‘Ah,’ said Marcus. ‘The others. Yes. Indeed. Well, my dear, it would appear to me that their chances of survival, are, to say the least of it, thin, very thin.’ He paused. ‘Very thin indeed,’ he mused.

‘Talk plain,’ said Madeleine perplexedly. ‘D’you mean you think the other five are going to . . .?’

‘Snuff it,’ said Marcus Aurelius shortly. And by next morning they had.

At sunrise Marcus left the cottage through a hole that emerged behind a stone flower-trough by the back door, and ran down the garden path towards the pigsty. Unable to stand the sight of the five weakening babies and, especially, the one that seemed to grow larger and stronger by the minute, he had spent the night alone in his newspaper bed, much of it in deep thought. Always his mind came back to Madeleine’s words. ‘Must be something I ate,’ she had said.

The pigsty was really a double one, but the cottagers, since they only ever fattened one pig at a time, used the other half of the covered-in section as a food store. In spring and summer time the mice found this an admirable arrangement, but in the autumn the pig would disappear, they never knew where, and there would be no food in the store.

Now, as Marcus ran up the drainhole into the sty, there was nothing in the outer run but a lingering smell of disinfectant. Inside was the empty staging, and, next door, the food store, swept clean of the last particles of barley meal.

But on top of one of the meal bins, Marcus noticed, was a large cardboard packet, and he ran up the wall and scuttled across to look at it.

At first he could not decipher the printed writing on it, but then he realized it had been left upside down. He hung head downward from the top of it, balancing himself with his long tail, and could now clearly read it:

Pennyfeather’s Patent Porker Pills

Add one pill per day to a normal fattening ration

You will be amazed at the weight gain

There followed a long selection of extracts from letters from satisfied users and a list of the various ingredients of the pills, and then finally a single sentence, printed in red capitals:

WARNING: DO NOT EXCEED

THE STATED DOSE

‘Oh no,’ said Marcus Aurelius to himself, ‘she could not have done so foolish a thing. Surely not? No, no, the packet is unopened. They cannot long have bought it. It must be for next year’s pig.’

He slid down the packet and ran all round it. And there, in the back bottom corner, was a small hole, a hole which something had nibbled, a hole which, as he nudged at it with his nose, expelled one round shiny white pill, the size of an aspirin.

Marcus ran out of the pigsty and back up the path to the cottage. So preoccupied was he with his whirling thoughts that he almost bumped into the cat as it came out of the flap in the back door.

Once in the family home, he confronted his wife as she lay and nursed the giant child, alone now in the nest.

‘Maddie, my dear,’ said Marcus Aurelius. ‘Recently, that is to say, in our summer residence, did you eat anything at all out of the ordinary?’

‘I don’t think so, Markie,’ replied Madeleine. ‘Though of course we all do tend to fancy some funny things at these times. No, just barley meal, bit of flaked maize, the pick of the pigswill. Oh, wait a minute though. There was a cardboard packet on top of the bin, had some big round sweets in it. I opened it up myself just about the time these babies – this baby, I do mean, oh dear! – was started. I fancied them, Markie, they was nice! I ate one every day.’

‘Oh, Maddie, Maddie!’ said Marcus Aurelius, more in sorrow than in anger. ‘Did you not read what was written on that packet?’

‘Don’t be silly, Markie dear,’ said Madeleine comfortably. ‘You knows I can’t read.’