TWO

Nasty Cat!

If only Madeleine had let well alone. If, that is, you could say that things were well, when the monster baby mouse, now three weeks old, was already almost as big as his mother and constantly, incessantly, demanding food.

At first Madeleine tried to manage alone, not wishing to disturb Marcus Aurelius from his regular routine of reading and contemplation, but the strain of constant foraging to supplement her dwindling milk supply was too much for her; and soon both parents were continually on the run, searching everywhere for anything remotely edible to offer to the ravenous baby, like two little birds feeding a cuckoo child.

But if only Madeleine could have left it at that. Perhaps they would have managed somehow. Perhaps the creature would not have become much larger, for its rate of growth did seem to be slowing down.

As it was, there came a morning when she said to her husband, tiredly (for they had been up all night scavenging), ‘It’s no good, Markie, we’ll have to try those sweets.’

‘Sweets, my dear?’ panted Marcus Aurelius, breathless from the effort of dragging into the nest a crust of bread, fallen from the cottagers’ table. ‘What sweets?’

‘The ones in that packet,’ said Madeleine. ‘The ones I was telling you about. Down at our summer house. You know. I took them. When I was expecting. I found them ever so filling, so maybe they’d fill him up.’

Marcus peered consideringly at their son, who had already devoured most of the bread and was chomping his way through what was left with ceaselessly moving jaws.

‘Ah, the Porker Pills, my dear. Ahum. Would you really consider such a course of action to be wise?’

‘Dunno about wise,’ said Madeleine. ‘But we’d be fools not to try it. I’m fair working my claws to the bone for him. Listen to him now.’ The huge baby, his crust finished, was making loud use of his first and favourite word.

‘More!’ he yelled. ‘More! More!’

‘Well, Maddie,’ said Marcus Aurelius, ‘you may be right. But you must also ask yourself whether, in view of the season of the year and the sheer physical difficulties of transporting the material, such a course is practicable?’

‘Come again?’

‘Can we do it? Can we, in short, bunt, butt, shunt, shove or otherwise propel such an awkward object as a Porker Pill all the way up the path in the wind and rain? I make no mention of the cat.’

‘Mebbe not,’ said Madeleine, ‘but we don’t have to. We’ll go back down there, to the pigsty. And then he can make a proper pig of himself.’

‘It will be very cold,’ said Marcus doubtfully, for his newspaper nest in the sitting-room wall was no more than three feet from the fireplace and beautifully warm in winter.

‘It won’t be for long,’ said Madeleine. ‘He’ll soon be able to look after himself and then we can come back indoors. And there’s another thing. We’ll have to get him out of here soon anyways or he won’t never get out. He’ll be too big.’

Some days later, when they made the move, the truth of Madeleine’s words was plain to see, for it took the combined efforts of both parents to force the massive body of their child through the hole behind the stone flower-trough. They had chosen their moment carefully. The cottagers were at work at the other end of the garden, and the cat, Marcus had carefully noted, was asleep in front of the sitting-room fire. Madeleine made haste down the path, calling to her son to follow, for he was inclined to linger and investigate the strange sights and smells of the outside world. Behind him Marcus Aurelius fussed and fretted, anxious to be under cover. In his agitation he actually resorted to the use of slang.

‘Skedaddle, lad!’ he cried to the lumbering infant. ‘Stir your stumps! Look lively! Put your foot down! Get your skates on! Step on the gas!’

‘He means “hurry”!’ cried Madeleine over her shoulder.

As they neared safety a strange thing happened. A blackbird, disturbed from the nearby hedge, flew suddenly low over the three mice with a loud cry of alarm. Madeleine shot into the drainhole of the sty while Marcus instinctively froze in his tracks. But the great baby, far from showing fear, made an angry leap at the bird as it passed and chattered shrilly with rage, his little jaws clacking together upon the empty air.

Once inside the food store, the parents’ first action was to nose out from the packet one of Pennyfeather’s Patent Porker Pills. Having rolled it on to the floor, they manoeuvred it under the wooden staging where their waiting child immediately fell upon it with little grunts of greed. They watched him, awestruck.

‘Do you know, Maddie,’ said Marcus Aurelius in a low voice, ‘that not only was he not frightened by that blackbird, but he actually tried to assail it?’

‘Assail it?’

‘Attack it. Have a go at it.’

‘Never!’

‘He did, I give you my word.’

Madeleine shook her head in bewilderment as they watched this strange son of theirs gorging upon the Porker Pill.

‘He hasn’t got a name, Markie,’ she said in a distracted voice. ‘I was thinking just now, when I called him to hurry. We must give him a name, it don’t make no sense to go on calling him Baby like I’ve been doing.’

‘Very true, my dear,’ said Marcus. ‘Undoubtedly he needs a name befitting his great size.’

‘Well, that ought to be easy enough,’ said Madeleine. ‘I remember you telling me your family nest was lined with pages from dictionaries and lexicons and suchlike when you was up at Oxford. What’s the Latin for “great”?’

‘Magnus.’

‘Magnus,’ said Madeleine consideringly. ‘I like the sound of that. Yes. We’ll call him Magnus.’ And as if to celebrate the occasion, the newly named Magnus set up his customary cry of ‘More! More!’ and off went his parents to fetch another pill.

By midday he had eaten three. He lay, sated and asleep at last, in the old summer nest of hay and straw and dried moss, and it seemed to Madeleine and Marcus Aurelius that he had grown appreciably in size since the morning. A fourth Porker Pill was clasped in his powerful forearms, ready for the moment of waking.

‘They don’t seem to have done him no harm,’ said Madeleine.

‘Certainly that voracious appetite would seem, if only temporarily, to have been gratified,’ said Marcus.

‘You mean he’s had enough.’

‘Just so. Indeed it occurs to me that, were we to supply the boy –’

‘Magnus.’

‘– were we to supply Magnus with an adequate ration – a dozen of these things should last him for some long time – we might leave him here and return to the cottage. I find this place distinctly chilly.’

‘Chilly?’ said Madeleine in a voice that was positively icy. ‘Marcus Aurelius, you find it chilly, do you?’

Marcus flinched inwardly at her use of his full and proper name, a sure sign of trouble, but he persisted bravely. ‘Indeed I do, my dear. I am no longer a young mouse, you know.’

‘But Magnus,’ said Madeleine distinctly, ‘is a young mouse. A very young mouse. Don’t you think he might find it chilly? All by himself?’

‘I doubt it, my dear,’ said Marcus earnestly. ‘The young do not feel the cold as we older ones do. And the boy, er, Magnus, that is, has a thick coat of hair now, very thick.’ He paused. ‘Very thick indeed.’

‘Marcus Aurelius!’

‘Yes, dear?’

‘Scarper!’

‘I beg your pardon, my dear?’

‘Push off!’ said Madeleine angrily.

‘But . . . what about you?’

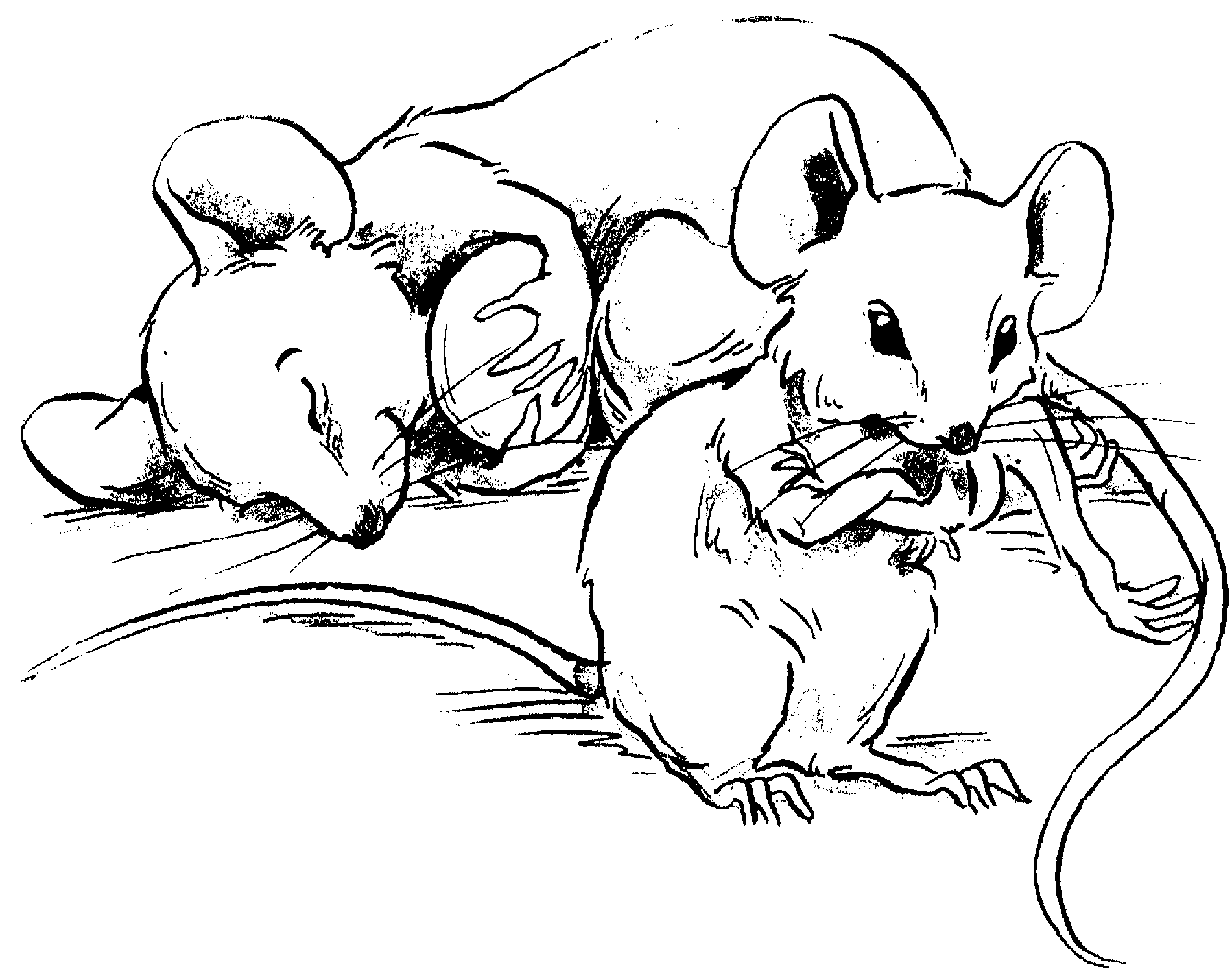

‘Me? I shall stay with little Magnus of course,’ said Madeleine, and she ranged herself protectively alongside the sleeping infant, now nearly twice her size.

Marcus Aurelius was sorely tempted to leave. The afternoon air was indeed cold, and the picture of himself curled up in his fireside nest with an interesting extract from The Somerset Guardian was clear in his mind. But what he would have decided was not to be known, for at that moment there was a heavy thump on the wooden staging above their heads and the air of the pigsty was filled with the strong reek of cat.

The sleeping baby awoke. His first action was to take a bite from the pill which he held, but, this done, he raised a questing nose.

‘Nasty!’ said Magnus loudly.

‘Shhh, dear,’ whispered Madeleine, ‘it’s only an old cat. Just you keep still and quiet, there’s a good boy.’

‘Nasty cat!’ said Magnus with a shout, and the tip of the cat’s tail, which hung down between a crack in the boards as it sat directly above them, twitched sharply at the sound of the squeak.

‘Your mother is right, Magnus,’ said Marcus Aurelius in a low voice. ‘Our best course of action is to preserve silence and to remain unmoving. We are quite safe in our present location. Eventually, if I do not miss my guess, and I may tell you that I have a vast amount of experience in these matters, very vast –’ he paused ‘– very vast indeed – eventually, as I was saying, the creature will fall victim to boredom –’

‘So shall us all,’ said Madeleine under her breath.

‘– and go away.’

‘Bite you!!’ yelled Magnus at the top of his voice.

‘No, it won’t bite you, my love,’ said Madeleine soothingly. ‘It can’t get in under here, you see, it’s too –’ But before she could finish Magnus threw aside his pill and rose stiff-legged from the nest, his eyes snapping, his coat-hair standing on end.

‘Bite you!!’ he cried again, and leaping forward, he fastened his needle teeth in the dangling tail-tip.

There was a split second of absolute silence and then an explosion of sound and movement above. Madeleine and Marcus Aurelius stared at one another in horror. Of Magnus there was no sign.