SIX

Magnus Earns His Name

When Magnus had finished the last of the Porker Pills which his mother had put ready for him the previous day, his first action was of course to yell for more. Receiving no response (for his parents were even then confronting the rabbit), he squeezed his bulk out from under the staging in the pigsty and went next door. There on top of the meal bin stood the magic packet, and Magnus’s greed drove him to make the climb up to it for the first time in his spoiled young life. It was empty.

In fury and frustration Magnus ripped the cardboard packet to bits with his razor-sharp teeth. He leaped down and dashed angrily into the garden, and in the wind of his passing a scrap of cardboard blew off the bin and fluttered gently down to the ground: You will be amazed at the weight gain, it read.

At first Magnus ran aimlessly about the cottage garden, his uplifted nose searching the air for food smells. He found a very small piece of fat that had fallen from the bird table, and one, the last, of the previous season’s apple fallings, half rotten, but apart from these there were only vegetables – spring cabbages, winter-sown broad beans, and Brussels sprouts. Among these last he stopped and shouted his usual request.

Instinctively, when the cat-flap squeaked, Madeleine shot in through the wire of the hutch door, but it was Magnus’s safety that she was immediately concerned for.

‘Quickly, my baby!’ she cried at the top of her voice. ‘Over here! Run over here! We be both in the rabbit hutch!’

‘We are both in the rabbit hutch,’ said Marcus Aurelius.

‘I knows that, stupid!’ said Madeleine exasperatedly. ‘We wants to get our Magnus in here too.’

‘How?’ said Marcus.

‘Your husband has a point,’ said Roland. ‘Now that one has actually seen your boy, one begins to realize the problems involved. Is there nowhere else he could seek safety?’

Before Madeleine could answer, the cat came round the corner of the cottage. Immediately it caught sight of Magnus and it stood up very tall, its ears pricked. Then it bounded into the Brussels sprout forest.

In the hutch all was confusion and noise as Roland gave a series of warning thumps with his hind feet and scrabbled madly but fruitlessly at the wire with his forepaws, while the little mice bombarded their son with frantic advice.

‘Run for the pigsty!’

‘Run for the tool shed!’

‘Run for the greenhouse!’

‘Run for the coal-hole!’

‘Run, Magnus! For the love of Cheddar, run!!’

And through all the hubbub Magnus stood staring blankly at them all, confused by the noise and unaware of the danger.

Then Roland’s deep voice rang out above. ‘Behind you, lad!’ he thundered. ‘Look behind you!’

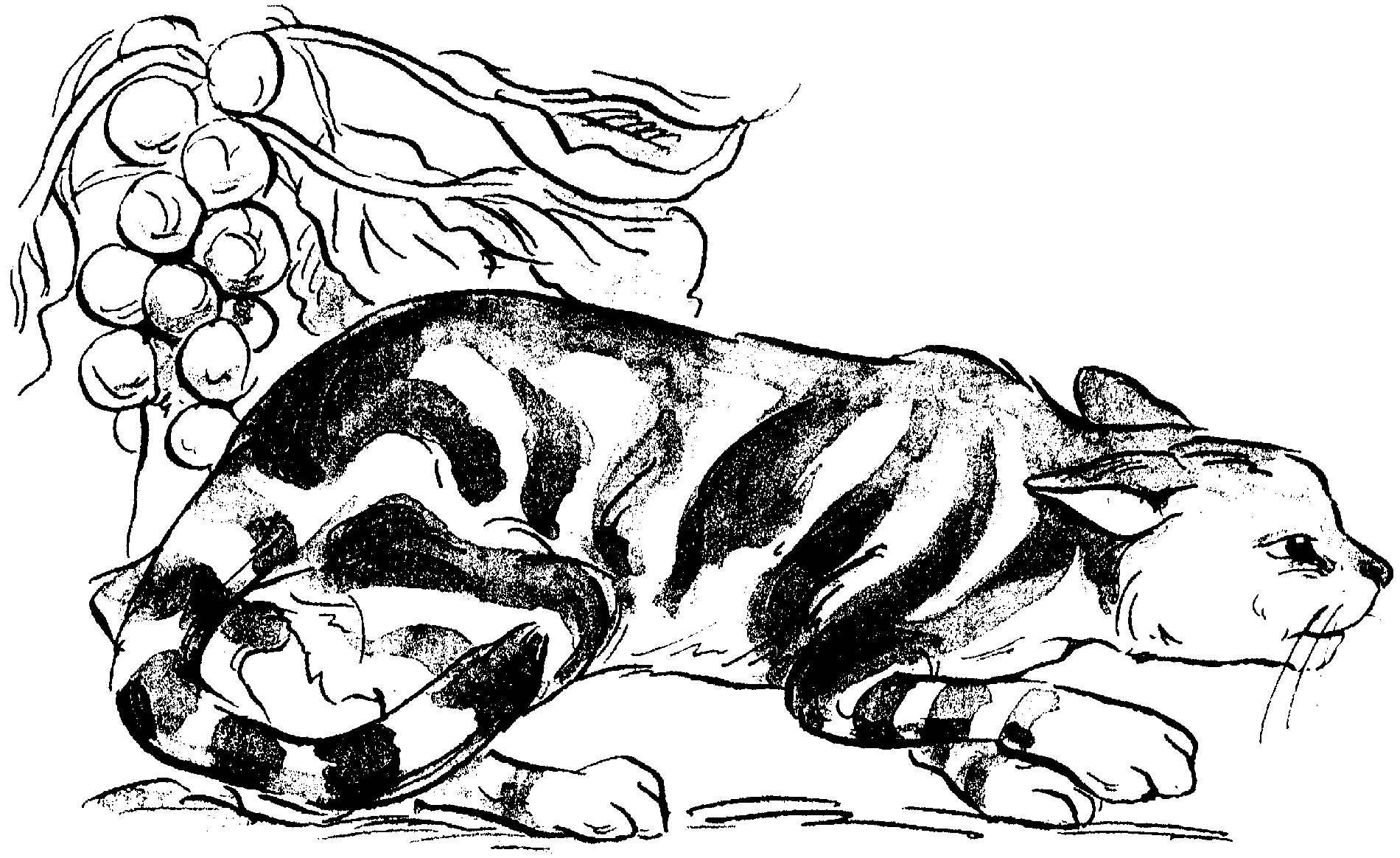

And as Magnus whirled the cat came creeping on its elbows out of the sprout forest, its ears flat to its head, the tip of that once-bitten tail twitching.

As the ancient Romans at the Coliseum looked down upon some wretched Christian awaiting the lion, so the three spectators in the rabbit hutch stared down upon the sacrificial scene. For though, unlike the Romans, they did not wish the cat to slay its helpless victim, they knew, like them, that inevitably it would.

‘Oh, my poor baby,’ whispered Madeleine.

‘Forever, and forever, farewell, Magnus!’ murmured Marcus Aurelius.

‘Brave lad!’ growled Roland softly. ‘He did not cut and run.’

And silence fell.

Slowly, nightmarishly slowly, the cat crept forward, until it was no more than a dozen feet from Magnus. It stopped and crouched, and the watchers waited helplessly for the final lightning rush and pounce, the remorseless end to every ordinary cat-and-mouse affair.

But though the cat was ordinary, the mouse was not. Magnus did not run, did not retreat an inch. Rather did he move a step towards the enemy, and as he did so his coat rose on end, with fright one might have thought, making him appear even bigger. But it was not fright, it was anger.

Tulip-eared, harsh coated, his long tail stiffly out behind him like a pointing dog, he moved a fraction nearer still. And the silence was broken.

‘Nasty cat,’ said Magnus distinctly, in a voice made all the more compelling by its unnatural quietness. ‘Nasty cat. Bite you.’

At these words a shudder of excitement passed through the three spectators, for two of them (Marcus was too short-sighted) saw the effect they had had upon the cat. It was, they saw, discomfited and suddenly it could not meet the approaching Magnus’s gaze. Very slowly, very slightly, it turned its head, so that its golden eyes were focused not upon Magnus, not upon the watchers in the hutch, but, by chance, upon the pigsty.

Now there was no knowing whether the cat could have remembered that painful incident of two months past, or whether, if it had, it would have connected the baby mouse scraped so casually off its tail-tip with the hulking threatening monster that was now not merely confronting but actually approaching it! But whatever its thoughts, once having looked away it could not make itself look back.

And all the time that Magnus continued to inch towards it, it crouched motionless, only the twitching of its tail, with anger one might have thought, making it appear even stiller. But it was not anger. It was fright.

And suddenly the watchers realized it.

‘Don’t go no further, my love!’ cried Madeleine. ‘Stop where you be now. The nasty old cat’s going to go away!’

‘The better part of valour is discretion!’ called Marcus Aurelius.

Roland alone had the wit to realize that this was the moment when the priceless shift in the balance of power brought about by Magnus’s stout-heartedness must not be let go to waste. The enemy must not be allowed the luxury of a dignified withdrawal. All that would lead to would be a deadly ambush for the gallant young mouse at a later date. Magnus must strike home!

Though Roland was slow of speech and movement, his brain was quick; and through it flashed a number of courses he might take at this vital moment. He could explain (‘Listen lad, now’s your chance, if you don’t take it, you’ll regret it later’ – too lengthy). He could taunt (‘Come on, lad, who’s afraid of the big bad pussy-cat then?’ – but Magnus patently was not). Or he could simply shout encouragement (‘Get in there, lad! Have a go! Knock his block off!’). But before he could open his mouth, having decided upon this last approach, the matter was settled for him.

All at once the cat’s nerve broke, for Magnus was now but a yard from it, and it rose and began to turn away. And as it swung round, lion-like no longer, Magnus made his move. With a most un-Christian lack of love for his enemy and a great cry of ‘Bite you!’ he sprang for the departing tail and once again fastened his jaws upon its ginger tip.

But how different was this from that first encounter! Five times as heavy, five times as strong, his long cutting teeth five times as sharp as on that other occasion, Magnus lay back and hauled like the anchorman in a tug-o’-war team as the now terrified cat made desperately for home.

Scrabbling madly at the ground, it somehow managed to drag its fierce assailant into the fringe of the forest of Brussels, only for Magnus to wrap his own tail around the strong stem of a sprout plant, and take the strain. Something had to give!

Suddenly, with a blood-curdling screech of pain, the cat broke free. But at what cost! For as it disappeared from their sight at speed, the watchers could see the spoils of victory hanging from Magnus’s jaws.

Slowly he came towards them, out of the blood-flecked Brussels sprouts, and like the matador who offers to the ringsiders the ear of the vanquished bull, laid on the ground below the hutch an inch of ginger tail-tip.

‘Nasty!’ said Magnus thoughtfully, cleaning his whiskers.

Above him there was pandemonium as the onlookers expressed their joy. ‘’E done ’im, ’e done ’im, ’e done thik girt ole moggy!’ squeaked Madeleine as she waltzed wildly around the floor in her excitement. As for Marcus Aurelius, only Latin was good enough for this moment. ‘Victor ludorum!’ he cried. ‘O Magnus magnificens, te salutamus!’

But it was Roland who unwittingly provided the title by which Maddie and Markie’s giant son was always to be known when future generations of mice spoke of his deeds.

‘What a lad you’ve got there!’ he boomed to the proud parents. ‘What size! What strength! Why, he’s a positive powerhouse!’

‘Powermouse, you means!’ said Madeleine with a squeal of laughter.

And so Magnus Powermouse got his name.